Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Origin

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

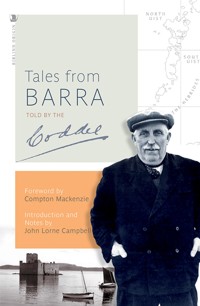

The Coddy was one of the most renowned storytellers and characters of the Western Isles at the turn of the nineteenth into the twentieth and beyond, and was the inspiration for Compton MacKenzie's Whisky Galore. His warmth and personality shine through these stories, which are a wonderful mix of myth, tradition and anecdote. This edition includes a large number of traditional tales told in the inimitable style of The Coddy, grouped in a number of themed sections: Tales of the Macneils of Barra and Other Lairds - The MacLeods of Dunvegan - The Laird of Boisdale - Stories of Olden Times - Ecclesiastical Traditions - Place-names - Tales of Treasure - Tales of Local Characters - Stories of the Politician - Stories of Sea Monsters - Fairies, Second Sight and Ghost Stories - Witchcraft. For any student of folklore, for anyone interested in the traditions and history of the islands, or for anyone who simply likes a tale well told, The Coddy is essential reading. This edition is enhanced with a plate section consisting of period photographs of the Western Isles and informative notes on The Coddy and his stories.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 305

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TALES FROM BARRA

________

TOLD BY THE CODDY

Tales From

BARRA

TOLD BY THE CODDY

JOHN MACPHERSON, NORTHBAY, BARRA, 1876–1955

Foreword by Compton Mackenzie

__________

Introduction and Notes by John Lorne Campbell

This edition first published in 2018 by

Birlinn Origin, an imprint of

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published by Birlinn Ltd in 1992

Reprinted 2001, 2004, 2008, 2014

Copyright © the Estate of John MacPherson 1992

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 91247 617 6

eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 977 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Geethik Technologies, India

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

FOREWORD, by Compton Mackenzie

PEDIGREES

INTRODUCTION, by J. L. Campbell

TALES OF THE MACNEILS OF BARRA AND OTHER LAIRDS:

*The Family Tree of the MacNeils

MacNeil who Fought at the Battle of Bannockburn

*MacNeil’s Raiding of Iona

*MacNeil of Barra, the Widow’s Son and the Shetland Buck

*MacNeil of Barra and Mackenzie of Kintail

*MacNeil’s Return to Barra from the Isle of Man

MacNeil and the Coming of Prince Charlie

Coddy’s Great-grandfather Neil MacNeil and the Prisoners of the Napoleonic War

MacNeil of Barra and the Butler, the Gardener and the Groom

THE MACLEODS OF DUNVEGAN:

Dunvegan Castle

MacLeod of Dunvegan and the Duke of Argyll

THE LAIRD OF BOISDALE:

*The Laird of Boisdale and the Bag of Meal

STORIES OF OLDEN TIMES:

*The Weaver of the Castle

The Life Story of the Little Weaver

The Emigrant Ship Admiral and the Barra Evictions

Inns and Ferries, and MacPhee the Ferryman’s Daughter

The Shebeeners of Kintail

The Drowning in Barra Sound

Tráigh Iais

ECCLESIASTICAL TRADITIONS:

Saint Barr

Saint Brendan

Father Dugan

PLACE NAMES:

Bogach na Faladh

Cnoc a’Chrochadair

Creag Gòraich

Gleann Dorcha

Port Chula Dhubhghaill

Tobar nan Ceann on Fuday

Arms on Fuday

TALES OF TREASURE:

The Dutch Ship Wrecked off Ard Greian

*The Tacksman of Sandray and the Crock of Gold

TALES OF LOCAL CHARACTERS:

Alexander Ferguson the Drover

John’s Sail to Mingulay

More About John

Alastair and the Tenth of May

Alastair and the Pigs

The Story of the Thrush

The Betrothal and Wedding of John the Fisherman

John the Fisherman’s Christmas Homecoming in a Blizzard

William MacGillivray and the Bagpipes Found at Culloden

STORIES OF THE POLITICIAN:

Medicine from the ‘Polly’

Hiding the ‘Polly’

Transporting the ‘Polly’

Another Tale of the Politician

STORIES OF SEA MONSTERS:

The Capture of the huge Basking Shark

The Sea Monster

Another Sea Monster

FAIRIES, SECOND SIGHT AND GHOST STORIES:

How Time was Lost in the Fairy Knoll

John the Postman and the Fairies

The Fairy Wedding on Hellisay

The Man taken from Canna by the Sluagh

MacAskill and the Second Sight

William and the Second Sight

Second Sight in Uist

The Frìth or Divination

The Manadh or Forewarning

The Mermaid

Crodh Mara - Sea Cattle

*The Water-Horse

Uaimh an Òir, the Cave of Gold

The Story of the Giant’s Fist at Bagh Hartabhagh

The Story of the Ghost and the Plank

*Mary and George

How Donald met the Ghost of Alexander MacDonald, the Famous Bard

WITCHCRAFT:

*The Witches who went Fishing with a Sieve

The Little Witch of Sleat

*The Barraman who was Bewitched by the Woman to whom he gave Grazing for her Cow

NOTE ON THE SECOND EDITION

GAELIC TEXTS:

Mac Nill Bharraidh, Mac na Banntraich, agus am Boc Sealtainneach

Fear Shanndraidh Agus an Guirmein

Na Tri Snaoidhmeannan

BIBLIOGRAPHY

________

*Wire recordings of these stories made from the Coddy by the editor are in existence.

Foreword

I met the Coddy first at the Inverness Mòd in 1928 and made up my mind immediately that I must lose no time in visiting Barra in order to enjoy more of as good company as I have ever known. This collection of his tales with which my old friend John Campbell has put us in his debt needs no bush of words from me to proclaim the quality of such a vintage: it is evident. There are happily still many who will read these tales and hear the voice of the Coddy telling them, but I am sadly aware of my own inability to evoke him on the page for those who knew him not. His wit was constant, and, though usually inspired by the humour of the moment, he was able to retain it in his correspondence. The briefest letter from the Coddy had always a phrase to make it memorable, and I never received a letter from him but I wished I were with him, and that is a precious rarity in my correspondence today.

The Coddy had an infallible sense of a man’s worth. I never knew him ‘put his money’ on an impostor. The socially pretentious, the bore, the sponger, the sentimentalist, the romantic liar never misled him into accepting their own opinion of themselves: he had a deadly objectivity. He possessed a remarkable gift which he shared with the Cheshire Cat of being able to disengage himself from present company while apparently he was still there. In his case what remained was not a smile but a pair of intensely blue eyes of which those who were familiar with them knew that the owner was no longer there.

Self-possession was one of the Coddy’s characteristics, but it had not been granted to him by a good fairy at birth. We were driving round Barra once, and at Allt the Coddy stopped the car.

‘I want to show you something,’ he said to me when we alighted. ‘This was the very spot where I made up my mind when I was young that I was as good as other people. I had always felt awkward when I was selling the fish and I said to myself, ‘You can sell fish against anybody, and you must understand that and not feel awkward. And I went on my way to Castlebay and from that moment I felt I was as good as anybody.’

Yet there were moments when that self-consciousness of youth he conquered once upon a time would assert itself. I remember a Corpus Christi procession in which he and I were taking part. The Coddy was to carry the crucifix at the head of the procession, and as he came out of the sacristy in cassock and cotta he noticed that Ninian, his youngest son, was laughing with another altar-boy.

The Coddy was not prepared for me to see him an object of mirth for the youth of Northbay. He must laugh at himself first.

‘Direct from the Vatican,’ he said to me, in that voice of mock solemnity which those who ever heard it will so much regret that they will never be able to hear again.

One of the innumerable pleasures of the years I lived in Barra was visiting with the Coddy the small isles about it that were no longer inhabited, because he was able to conjure up from the past those who within his own memory had been the life of them, Fuday, Fiaray, Hellisay, Sandray, Pabbay, Mingulay, Berneray ... every name like the gnomon of a sun-dial records for me only the sunny hours, and on every one of them it is always a blue summer sky with the machair in fullest flower and reminiscence from the Coddy flowing like the tide.

One curious vice the Coddy had (I do not apologise for the strength of the word), and that was to suppose that whisky was improved by diluting it with fizzy lemonade. I recall a visit to Barra by Lochiel, Charles Tinker and Alasdair Fraser of Lovat as repre sentatives of the Inverness-shire County Council of which the Coddy was the Member for the north end of the island. Hospitable always but on this occasion anxious to be particularly hospitable, the Coddy pressed upon them the suitability of the moment for refreshment. None was loth, and the Coddy retired to prepare the drams which he was determined should be drams de luxe. I can see now the expression of horror and incredulity upon the faces of his three prized guests as they tasted the liquor.

‘My God, what’s this?’ Charlie Tinker gasped.

And the Coddy, raising both hands in a sursum corda of devout benison, said proudly: ‘Whisky and lemonade.’

One more story. On a glorious June morning the Coddy and I had gone down to greet Eric Linklater’s arrival with his bride for their honeymoon in Barra, and on the way down to the pier I was beckoned to by a citizen of Castlebay with whom the Coddy was not on the most cordial terms. I went into his shop, and later joined the Coddy on the pier.

‘Well, Coddy,’ I told him, ‘I’ve just been given something you were never given by X–Y–.’

‘What was that?’

‘Two drams, It’s his birthday.’

‘A Dhia!’the Coddy exclaimed in sombre marvel. ‘Fancy a man like that to be born in the month of June!’

I shall not hear again the gurgle of the Coddy’s pipe nor see the ritual of expectoration that concluded the lighting of it, but as I write these words he is sitting on the other side of the fire as vivid and as much loved a figure in memory as he was in my life. He rests now by the Oitir Mhòr which he loved so dearly, and it is my hope that one day I shall rest near him and other old friends in the last cèilidh of all.

COMPTON MACKENZIE

MACNEIL OF BARRA PEDIGREE

N.B. – There is a Barra tradition that Gilleonan was older than Roderick but was passed over. In a similar way it appears that the MacNeils of Vatersay are descended from Niall Uibhisteach who lost the succession to a usurping illegitimate brother around 1615.

CODDY’S FAMILY TREE

Angus MacPherson had brothers; Cathelus, grandfather of Roderick MacMillan, Gerinish. Donald, who lived at Griminish, and had a daughter Catherine, mother of Lachy Bàn, the famous piper.

Introduction

My first meeting with the Coddy – a nickname bestowed in boyhood and persisting, like so many Barra nicknames, throughout a lifetime – was a brief one in August 1928. Later the same year I had the pleasure of travelling with him by bus on the old Loch Nessside road from Fort William to Inverness, where we were both going to attend a Mòd, and Coddy, who represented the northern half of Barra on the Inverness-shire County Council, was also to attend a Council meeting. An invitation to return to Barra for the purpose of studying colloquial Gaelic was warmly extended. My only regret now is that I was unable to take advantage of it until 1933.

Coddy was in appearance rather short, thick-set and Napoleonic; he had an extremely fine-looking head and was quick of movement – and of speech, whether in English or Gaelic. His MacPherson forebears came originally from Benbecula. Sixty years ago the late Fr Allan McDonald of Eriskay recorded a South Uist saying, ‘Geurainich Chlann Mhuirich’, ‘Geuraineach, a smart-tongued fellow. The MacPhersons or Curries or MacVurichs are considered sharp on their tongues and apt scholars.’ This was very true of the Coddy, one of whose chief characteristics was aptness of speech, both in Gaelic and English, and a talent for both anecdote and diplomacy which might, as I have heard it said, have made him Mayor of a large American city, had he been a citizen of that republic. As it was, his talents did much for his native island, and delighted a very large circle of friends.

There is considerable interest in Coddy’s family tree. It belies completely the popular notion that the inhabitants of the Outer Hebrides formed isolated and inbred communities. On the paternal side his people came from Benbecula and South Uist, on the maternal from the Island of Mull, both sides eventually marrying into Barra families after settling on the island, so that both the Coddy’s grandmothers, Mary MacNeil and Flora MacPhee, were Barra-born. But perhaps his descent can best be described in the words of his eldest daughter, Miss Kate MacPherson, into which I have interpolated some dates and other information obtained from the Barra Baptismal Register and from Mr Roderick MacMillan, Gerinish, South Uist, one of Coddy’s cousins.

Miss Kate MacPherson writes: ‘My father’s maternal grandfather, Robert MacLachlan, was gardener at Aros Castle in Mull and came from there to be gardener for Colonel MacNeil of Barra at Eoligarry. When telling this, my father always said that his grandfather came to Barra ‘after the Napoleonic wars,’ but apart from that I regret I cannot give a date. Robert MacLachlan became a Catholic and married Flora MacPhee’ [daughter of Alexander Macphee, Vaslain, and Flora Maclnnes, Greian, his wife, born 6th September 1815. The marriage took place at Eoligarry on 10th March 1834 and was performed by Fr Neil MacDonald]. ‘Robert and Flora subsequently moved to Talisker in Skye, but later returned to Barra and settled on a croft at Buaile nam Bodach. My great-grandmother brought her children from Skye to be baptized at Craigstone.’ [Of the five youngest children of Robert MacLachlan and Flora MacPhee, Archibald was born on 3rd April 1840 and baptized on 23rd August of the same year; Janet was born on 4th November 1841 and baptized on 22nd June 1844; and Margaret born on 15th April 1843, Ann (Coddy’s mother), born on 11th November 1845, and Neil, born 12th June 1848, were all baptized together on 21st June 1848. It therefore looks as if Robert MacLachlan and his family left Barra not long after the sale of the estate to Colonel Gordon in 1838, when Eoligarry ceased to be a laird’s residence, and returned to Barra in 1848, when the potato famine may have made things difficult on Skye.]

‘One of their daughters, Ann, married Neil MacPherson – Niall mac Iain ’ic Aonghuis ’ic Caluim ’ic Iain. I am sorry I cannot go further with the sloinneadh, but my father’s cousin Roderick Mac Pherson tells me that my father could go back fourteen or fifteen generations. Ann and Neil settled with my great-grandfather, Robert MacLachlan, on the croft at Buaile nam Bodach, and there my father was born on 26th December 1876.

‘Now as to the MacPhersons. Iain and his father Angus were both joiners and came from South Uist to work on the priest’s house at Craigstone, Taigh a’ Ghearraidh Mhóir (the house of the big wall).’

[The priest in question was Fr Angus MacDonald, who was in Barra from 1805 to 1825, when he became Rector of the Scots College at Rome. Some of his correspondence is printed in the Book of Barra. His account book shows that Angus MacPherson came in April 1819 to start work on his house, bringing his wife Mary MacIntyre and his son Iain with him. Another son, Lachlan MacPherson, was born on Barra and baptized on 3rd April 1820, when his parents were described in the Barra baptismal register as ‘natives of South Uist, now residing in this parish,’ and the godfather was Allan MacArthur of the sloop Maid. Angus MacPherson, besides being a well-known joiner, was a bard. Here are two of his best-known songs, as taken down by Fr Allan McDonald in 1887 and 1897:

‘The following comical song was composed by a carpenter of the name of McPherson, commonly called Aonghus mac Caluim ’ic Iain:

Tha Siosalaich is Griogalaich tric ’ga mo bhòdadh,

Iad trom orm uile, ’s mi umhail gu leòr dhaibh,

Air son siochaire botuil bhith ’ga chosg’ san taigh òsda,

’S mi fhin bhith ’ga chosnadh le locraichean gròbaidh,

Mo chailin donn òg.

Chuir mi fios air an t-sagart bha stad anns an Iochdar,

Bho’n a bha e n’a dhotair gu socair dhomh dhianamh;

’S nuair bha e ’gam shealltainn, bha mo cheann-sa gun riaghailt,

’S ann thuirt e ‘Tha’m bàs ort, cha n-fhàg e thu ’n dìochainn,’

Mo chailin donn òg.

’S tric tha mi smaointinn na daoine nach maireann

A dh’òladh ’s a phàigheadh ’s nach fhàgadh mi falamh

Nam biodh fios agam fhìn nach eil sìth aig an anam

’S e ’n obair nach fhiach a bhith dianamh an drama,

No idir ’ga h-ò1.

Tha mo bhean-sa air a marbhadh a’ falbh feadh an fhearainn,

A’ tional ’s ag iarraidh gach sian dhomh gu fallus,

A dh’aindeoin a pianadh ’s a riasladh ’s a caithris,

A dh’aindeoin a saothair, tha ’n saor gu bhith thairis,

Mo chailin donn òg.

Ach ma leighiseas mo shùilean, bheir mi ’n ionnsaigh so fhathast,

Null far a’ chaoil far bheil gaolach nam fearaibh,

Far bheil ceannard na cléire nach leubhadh a’ ghainne,

’S beag iùnadh do threud gun dhol ceum ann am mearachd,

Mo chailin donn òg.’

Translation

‘Chisholms and MacGregors are often putting me under the pledge, they are all hard on me, though I am obedient enough to them, because I consumed a trifling bottle at the inn, which I earned with grooving planes – My young brown lass (chorus).

I sent for the priest who was living at Iochdar, because he was a doctor, to restore me to health; when he was looking at me, my head was out of order; he said, ‘Death is coming for you, he will not leave you forgotten’ – My young brown lass.

Often I think of the men once alive, who used to drink and pay and would not leave me empty; if I knew that their souls were not in peace, it would be worthless work to be taking a dram, or drinking one at all.

My wife is worn out going through the land, collecting and seeking every herb that would make me perspire; in spite of her pain and her discomfort and her watching, in spite of her work, the joiner [himself] is nearly done for – My young brown lass.

But if my eyes are cured, I will make the attempt yet to go across the sound [Barra Sound] where is the dearest of men; where there is the chief of the clergy who does not expatiate on scarcity; little wonder your flock does not go one step into error – My young brown lass.’

Fr Allan says that, ‘The Siosalach and Griogalach were the Rev. John Chisholm of Bornish and the Rev. James MacGregor of Iochdar. The priest of Barra was the Rev. Neil McDonald who died afterwards at Drimnin, Morvern.’

The priest of Barra must, however, have been the Rev. Angus MacDonald, for whom Angus MacPherson went to work in 1819 at Craigstone.

The other song is:

‘Oran a rinn Aonghus Mac Caluim do sgothaidh a bha ’m Barraidh [deleted, Cille Brighide substituted] ris an canadh iad “An Cuildheann” – Coolin Hills.

Hug a rì hu gu gù rìreamh

Air a’ bhàta làidir dhìonach,

Do Not Faro ’s do na h-Innsibh

Bheir i sgriob o thìr a h-eòlais.

Thug iad an Cuildheann a dh’ainm ort,

Beanntannan cho àrd ’s tha ’n Alba;

Cuiridh canbhas air falbh iad,

Ged tha siod ’na sheanchas neònach.

Gaoth an iardheas far an fhearainn,

’S ise ’g iarraidh tighinn a Bharraidh;

Chuir i air an t-sliasaid Canaidh,

’S bheat i ’n cala gu Maol-Dòmhnaich.

Bàta luchdmhor làidir dìonach

Gum bu slàn an làmh ’ga dianamh;

bheat i na bha ‘n taobh-sa Ghrianaig

Ach a cunntas liad ’san t—seòl dhi.

Gaoth an iardheas as an Lingidh

Toiseach lionaidh, struth ’na mhire,

’S ise mach iarradh gu tilleadh

Ach a gillean a bhith deònach.’

Translation

‘A song which Angus son of Calum made to a boat which was in Barra (deleted, and Kilbride substituted – Kilbride is in South Uist) which was called The Coolins.

Chorus: Hug a ri hu gu verily

On the strong watertight boat

To Not Faro and to the Indies

She will journey from her own country.

They called you “The Coolins,” mountains as high as any in Scotland; canvas will set them moving, though that is a strange tale.

The wind is in the south-west coming off the land, as she seeks to come to Barra; she left Canna on her beam, and beat into harbour to Muldonich.

A valuable, strong, watertight boat, may the hand that made her prosper; she beat what boats there are on this side of Greenock, only counting the breadth of the sail in her.

The south-west wind is off the sound [between Barra and Vatersay], flood tide starting, current playing; she would not ask to turn back as long as her lads were willing.’

[A version of eight verses, but lacking the fourth verse given here, was printed by Colm O Lochlainn in Deoch Slàinte nan Gillean, in which it is stated that the song was made by the Coddy’s great-uncle to the boat in which he and the Coddy’s great-grandfather came from Mull to Barra; but this can hardly be the case, for it was the Coddy’s maternal great-grandfather Robert MacLachlan who came from Mull to Barra, not Angus MacPherson, the bard, though this boat might have brought them.]

‘Iain MacPherson (Angus’s son) settled in Brevig, had a boat which he built himself, and was drowned on the Oitir. After his death his widow (Mary MacNeil) was evicted from the house in Brevig and went to live in Bruernish, near Northbay.’

[Iain’s son Niall married Ann MacLachlan, as has been stated.]

‘When my father left school, he started work lobster fishing with his father, and later worked on Donald William MacLeod’s boats line fishing and herring fishing.’ Donald William MacLeod was married to the Coddy’s aunt. ‘Probably about this time he joined the Royal Naval Reserve. One summer he had a very severe attack of pneumonia, and after that did not return to the fishing. Instead, he started working for Joseph MacLean, one of the leading Barra merchants, and became his fish salesman. This work took him to Skye, Lochboisdale, and, of course, to Castlebay (which was then a great herring curing centre). In the off-season he worked at Skallary and Northbay. In 1911 he got a croft at Northbay, built a house and set up a merchant’s business of his own, and in 1923 he was appointed Postmaster of Northbay.’

I continue the account with a quotation from the obituary printed in the Oban Times:

‘When cars came to the island he started a car and motor-hiring business with considerable success [actually I believe he had the first car ever imported into Barra, a model T Ford]. As the tourists began to flock to the island he decided to build a boarding house, and this was the “Coddy” in his element and at his very best. He was the genial host, the great story-teller and the charming fear-an-taighe. Many will remember pleasant hours spent in Taigh a’ Choddy listening to his fund of folk-lore told with feeling and sincerity. Most of these were told in Gaelic, but the “Coddy” was equally fluent in English.

‘It was not surprising to hear he had taken part in the film during the shooting of Whisky Galore on the island of Barra. In fact, with such a personality he could have had Hollywood at his feet. Indeed, it can be said that it is possible that the author would never have written the book if there had been no “Coddy”.

‘He served for a number of years on the Barra District Council and also on the County Council of Inverness, where he gave unstinted service to his island.

‘One of the many great qualities in his life was his devotion and loyalty to his church. He saw the church, St Barr at Northbay, go up, and he took a keen and leading interest in it all of his days. His fondness of children and his kindness and readiness to help when ever he was approached testified to his true Christian character.

‘In June 1944 he received a severe blow in the death of his second son, Neil, who was killed in action while serving with the R.A.F. This upset the Coddy very noticeably, and he was never quite the same again. For the past year he had been confined to the house with cardiac trouble, and the end came peacefully on the morning of 27th February, 1955.

‘After Requiem Mass in St Barr’s church, Northbay, he was laid to rest in the cemetery at Kilbar in Eoligarry, facing the Oitir Mhór of which he was so fond. To his widow and family of three sons and three daughters his very many friends offer their sincere condolences, and their farewell to the Coddy they express in the native tongue by that final prayer of the church:

Fois shìorruidh thoir dha, a Thighearna,

Agus solus nach dìbir dearrsadh air.’1

Coddy’s personality and talents as a host brought him before long a large number of visitors, some of them distinguished ones – their names are preserved in his green book – peers, politicians, officials, descendants of Barra emigrants to Canada and the U.S.A., scholars from Scotland, Norway and Gaelic Ireland, archaeologists, ornithologists, sportsmen and holiday-makers simply seeking a change and a rest in the peaceful unhurried atmosphere of pre-second war Barra, all made their way to the Coddy’s, attracted by his vigorous personality and the kindness and hospitality of his wife and family.

I did not know that Coddy’s house had become so popular when I returned to study colloquial Gaelic there in the summer of 1933. Conversation with English-speaking visitors, though often interesting, did not further these studies very much. But Coddy was assiduous in his teaching. I got no English from him. ‘Abair siod fhathast, Iain,’2 he used to say to me whenever I made an error in pronunciation or used the wrong word. As autumn drew on, and the visitors departed southwards with the puffins and other migrants, we got more time to ourselves to study the language which we both loved.

Twenty-odd years ago Barra was an island where, one felt, time had been standing still for generations. It is always extraordinarily difficult to convey the feeling and atmosphere of a community where oral tradition and the religious sense are still very much alive to people who have only known the atmosphere of the modern ephemeral, rapidly changing world of industrial civilisation. On the one hand there is a community of independent personalities where memories of men and events are often amazingly long (in the Gaelic-speaking Outer Hebrides they go back to Viking times a thousand years ago), and where there is an ever-present sense of the reality and existence of the other world of spiritual and psychic experience; on the other there is a standardised world where people live in a mental jumble of newspaper headlines and B.B.C. news bulletins, forgetting yesterday’s as they read or hear today’s, worrying themselves constantly about far-away events which they cannot possibly control, where memories are so short that men often do not know the names of their grandparents, and where the only real world seems to be the everyday material one. If it be the case that ‘Gaelic alone is not enough to keep a man alive’ and that therefore the Hebridean world of oral tradition must yield to the encroachment of mass semi-sophistication and anglicised education, so that the islanders be not cheated in the labour markets of the south, that does not mean that victory is going to the ‘better’ of the two contestants in the struggle, but simply that the material progress of the Islands is being achieved at the cost of cultural impoverishment, which makes one envy the more the Icelanders and Faeroese who have contrived to make the best of both worlds, and are retaining their ancient languages as instruments of modern culture and education, while bringing their material way of life up to date.

In the Barra of Coddy’s time, psychic experiences were still sufficiently frequent to maintain the particular character these have always given to the Hebrides, as can be seen from his stories. Material events, such as the evictions, the potato famine, the departure of the last of the old race of lairds in the direct line, the Napoleonic wars and the oppression of the pressgang, none of which happened later than 1851, seemed to be matters of yesterday. The Jacobite rising of 1745 and 1715 felt only a little farther back, and the events of the seventeenth century, the wars between Royalists and Covenanters, and the visits to Barra of the Irish Franciscans (1624–40) and the Vincentians (1652–57), of whom Fr Dermid Dugan was particularly well remembered, seemed only a very little earlier. Behind all this lay memories of the exploits of the old MacNeils of Barra, of the Lords of the Isles, and of the Viking invaders of Scotland and Ireland, who started coming in the ninth century: the island of Fuday in Barra Sound is said to have been the site of the last surviving community of Norsemen in the Barra district.

Next to none of this information, it need scarcely be said, was derived from printed books, still less from the formal compulsory school education given on the island, which was entirely in English from its inception in 1872 until 1918, when Gaelic was admitted as a permissive subject, and where the teaching of history was heavily coloured with the pro-Whig and anti-Highland bias of the standard Scottish text-books. The vehicle of Barra tradition was the Gaelic folk-tale, the anecdote, and the folk-song, of which thousands existed; a rich and varied tradition, but one which, lacking patrons, brought its practitioners no material reward. Here it was greatly to the Coddy’s credit that, unlike some Gaelic-speaking Highlanders who have made their way in the world, he never turned his back upon the language and traditions of the race to which he belonged, but was fully aware of their beauty and did his utmost to encourage those who were trying to preserve these things and prevent them from falling into oblivion. In this my friends and I have been heavily indebted to him.

In 1933 there were living within two miles or so of Coddy’s house Ruairi Iain Bhàin and his sister Bean Shomhairle Bhig, the two most outstanding folk-singers I have ever listened to; Seumas Iain Ghunnairigh, an excellent story-teller; Murchadh an Eilein, born and brought up on the now uninhabited island of Hellisay, and full of interesting stories and local traditions; Alasdair Aonghais Mhóir, a famous character and gifted raconteur; Neil Sinclair ‘An Sgoileir Ruadh’ Schoolmaster at Northbay, descended from Duncan Sinclair who lived on Barra Head,3 a beautiful speaker of Gaelic who took a most intelligent interest in his native language and aided many of the Gaelic students who visited Barra; and many others, including Miss Annie Johnston, well known to many folklorists, who lives in Castlebay. Doyen of all these was Fr John MacMillan, parish priest of Northbay, a native of Barra, great in heart and in body, a wonderful preacher in Gaelic, and a true poet. No student of Gaelic could wish for better surroundings and company. Looking back on those days my great regret is that we had not the means to record these tradition-bearers adequately before the Second World War broke out. In those days such work was entirely unrecognised in Scodand, though this was not the case in other countries such as Ireland, Scandinavia and America. I remember very well trying, in 1938, to find an institution in Scotland which could accept copies of recordings of traditional Gaelic songs made in Nova Scotia the preceding year. I could find none which had any provisions for accepting such a gift.

The process of getting inside the tradition itself was by no means easy. First the local dialect had to be learnt; here ‘book Gaelic’ was an actual obstacle. All spoken Scottish Gaelic dialects differ from the literary language, in some respects consistently: the dialects of the Outer Hebrides are, in fact, more vigorous than the modern literary language, and contain many words and expressions that are not in the printed dictionaries.4

Coddy was assiduous in assisting these studies. We used to go together to the houses of Seumas Iain Ghunnairigh or Alasdair Aonghais Mhóir in the winter evenings, when the story-telling and exchange of reminiscences would soon begin. At first I could hardly do more than pick out an occasional word or sentence here and there. I was just beginning to feel that I would never do more than this when suddenly things seemed to become clear, although, of course, there were (and are) still many difficulties to be overcome.

In January 1937, much to the Coddy’s interest, I was able to acquire a clockwork Ediphone, after having first tried and discarded a perfectly useless phonograph recommended by some foreign authority. This Ediphone interested the Coddy hugely and he was assiduous in finding people to record on it. In particular, he was anxious for the songs of Ruairi Iain Bhàin to be recorded: for Ruairi was getting old; his sister Bean Shombairle Bhig, a wonderful folk-singer, who had sung, to Mrs. Kennedy Fraser, was in ill health and unable to sing again.

In July 1937 my wife and I, who had made our home in one of Coddy’s houses since 1935, left with the Ediphone to record old Gaelic songs from the descendants of Barra emigrants in Cape Breton,5 amongst whom we found the same songs still preserved by the old people; that is another story. On our return to Barra in 1938 I brought a Presto J disc recorder with which I was in time to re-record Ruairi Iain Bhàin and a number of other singers; some of these recordings with a book of words were published by the Linguaphone Institute in 1950, greatly to the Coddy’s joy. When I visited Barra again between 1949 and 1951 with a wire recorder, Coddy was again to the fore in encouraging the work, and recorded Gaelic versions of twelve of the anecdotes which are printed here. He realised perfectly well what so few realise: that the Gaelic oral tradition is an immense tradition containing many things of beauty and interest, and a great deal of it had already perished irrevocably, and that unless a desperate effort were made, most of the rest would perish too, especially the old songs in their authentic form. ‘Ah, Iain,’ he used to say, ‘if only you had come around with that machine twenty years ago, what wouldn’t you have got from the men and women who have passed away. You could never believe how much has been forgotten.’

In the spring of 1951 I made my last visit to the Isle of Barra with the wire recorder, accompanied by Mr Francis Collinson, who had just been given a Research Fellowship in folk-music at Edinburgh University. As usual, the Coddy was to the fore in encouraging the work and, of course, we stayed at his house at Northbay, where another visitor was Miss Sheila J. Lockett, on a holiday from London. After hearing some of the Coddy’s tales, Miss Lockett was so much struck by their interest and the vividness of the Coddy’s style, that she suggested they would be well worth taking down in shorthand. This was eventually arranged, and later in 1951 and in 1952 Miss Lockett made a number of visits to Northbay for this purpose, taking the stories down in the Coddy’s own words, just in time before his memory began to fail. Miss Lockett, whose name should be known to students of Scottish Gaelic folklore in connection with the part she has played in drawing the music which is printed in Folksongs and Folklore of South Uist, and in preparing this work and Fr Allan McDonald’s Gaelic Words from South Uist for the press.

A word on the history of Barra will not be out of place here, for it is a constant background to these stories. Traditionally the name of the island is associated with St Finbarr of Cork who lived in the sixth century. St Finbarr, whose story can be read in Charles Plummer’s Lives of the Irish Saints, was undoubtedly a powerful saint, but there is no record of his ever having been in Scotland. More probably the church was dedicated to him by one of his pupils. At any rate, the memory of St Barr is still vivid in Barra. Down to the seventeenth century it was popularly believed that dust from the burial ground named after him at Eoligarry, scattered on the sea, would result in the calming of storms, and even later his statue was preserved in the church there, as is mentioned by Fr Cornelius Ward (1625) and Martin Martin (1690). This statue, indeed, may still exist somewhere in concealment.

In the ninth century came the Norsemen, who left their mark in the form of Viking burials, popular traditions and place-names like ‘Breibhig’ (Broad Bay),’ ‘Alla’asdail’ (Elves’ Milking-place), ‘Hellisay’ (Cave Island) and so on. Grettissaga