7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

By the summer of 1940, the overwhelming might of the German air force had triumphed over Poland, Norway, France, Holland and Belgium. As the fighters and bombers of the Luftwaffe amassed on the north west coast of Europe, they had no reason to believe that the heavily outnumbered squadrons of the Royal Air Force (RAF) would prove any more difficult to overcome than their earlier opponents. However, these illusions of invulnerability were soon to be shattered in whirling combats over southern England in the conflict that would be known as the Battle of Britain.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 545

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

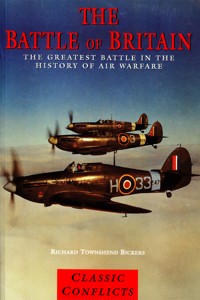

CLASSIC CONFLICTS

THE BATTLEOF BRITAIN

CLASSIC CONFLICTS

THE BATTLEOF BRITAIN

THE GREATEST BATTLE IN THE HISTORY OF AIR WARFARE

RICHARD TOWNSHEND BICKERS

FOREWORD BY AIR MARSHAL SIR DENIS CROWLEY-MILLING KCB, CBE, DSO, DFC, AE

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Air Marshal Sir Denis Crowley-Milling, KCB, CBE, DSO, DFC, AE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PRELUDE TO BATTLE

Richard Townshend Bickers

THE RAF

Richard Townshend Bickers

AIRCRAFT OF THE RAF

Gordon Swanborough

THE LUFTWAFFE

Richard Townshend Bickers

AIRCRAFT OF THE LUFTWAFFE

William Green

THE SUPPORT TEAMS

Bill Gunston

BATTLE TACTICS

Air Vice-Marshal J. E. (Johnnie) Johnson, CB, CBE, DSO, DFC, DL

THE HEIGHT OF THE BATTLE

Mike Spick

BATTLE DAY OF AN RAF PILOT

Richard Townshend Bickers

BATTLE DAY OF A LUFTWAFFE PILOT

Richard Townshend Bickers

BATTLE SUMMARY

Group Captain Sir Hugh Dundas, CBE, DSO, DFC, DL

BATTLE DIARY

Richard Townshend Bickers

RAF HEROES

Richard Townshend Bickers

INDEX

C. J. Davies

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book like this would be impossible to produce without the help of many individuals and organisations, and the publishers are grateful to everyone who contributed to the success of this project. We would like to thank all who helped by granting interviews and giving permission to use personal memoirs and quotes. Special thanks are due to: David Bickers and the Douglas Bader Foundation; Air Chief Marshal Sir Christopher Foxley-Norris, GCB, DSO, OBE, and Wing Commander N. P. W. Hancock, DFC, of the Battle of Britain Fighter Association; Air Vice-Marshal A. V. R. (Sandy) Johnstone, CB, DFC, AE, DL; Andrew Cormack and the staff of the RAF Museum at Hendon; Lt. Col. Dr. Dieter Rogge, Oberlieutnant Peter-Jorg Wiesener, Regierungs-oberinspektor Hartmann and the staff of the Luftwaffenmuseum in Hamburg; Andy Saunders and the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum Trust; Tony Gilberts and the 39/45 Warbirds Club; the late Paul Smith; and the RAF Air Historical Branch.

FOREWORD

Some people may think that, over the years, more than enough books have been written on the Battle of Britain and there can be little new ground to cover. I believe, however, that this volume comes as a timely reminder of what was at stake in those dark hours of 1940. So let us consider for a moment, more than half a century on, how different history would have been had the German air force gained that vital air superiority over Britain – so necessary before there could be any thought of the invasion that Goering had boasted could be launched within a matter of weeks, with forces moving across the Channel unmolested by air attack to achieve final occupation.

First, there would have been no American intervention and support in arms or men, no massive bombing offensive against Germany, and no base from which to launch a second front. Hitler’s war machine could have been largely committed to the defeat of Russia and under these circumstances it could well have been successful. Also, having no disruption in their nuclear research and development work, it is conceivable that Germany would have had the atomic bomb within a few years, thus further strengthening her position as the master of Europe. Britain could well have been an occupied country to this day.

So I believe it is right that we, as a nation, should once again be invited to look back to a time in history, now half a century ago, which proved to be the turning point leading to the eventual defeat of Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

1940 was the year that air power truly came of age. The success of all campaigns that followed depended heavily upon gaining and sustaining air superiority. When General Montgomery (as he then was) returned home in triumph after the battle of Alamein I was present at a talk he gave at Camberley. He told us in his forthright manner that he had rewritten ‘the principles of war’ and his first new principle was, as he put it, ‘to win my air battle’. He never moved his forces without being sure of his air cover from then on.

This new publication also brings to mind some of the vital factors affecting the outcome, some happening well before, and others during, the Battle. For instance, the British public to some extent still look down on Neville Chamberlain for deceiving the country in September 1938 with ‘peace in our time’ and with the Munich agreement and appeasement of Hitler, but it is clear that Chamberlain was not deceived by Hitler, and in fact, on his return, accelerated the rearmament programme.

Admittedly, the situation in 1938, had we gone to war, would have been different in many ways. But had events then led to the Germans reaching the Channel, it is worth recording that we would have had only 70 Hurricanes and 9 Spitfires in the front line. Also, the radar detection and fighter control systems, the creation of which Air Chief Marshal Dowding had played a major role in, were still incomplete. It is of interest that the German air force, in their written appreciation covering Operation ‘Sea Lion’ (their invasion plan), acknowledged the existence of our radar stations, but showed no knowledge of the use of the information for controlling the fighter force which had been developed to such great effect. In fact, it came as a great surprise to them to find the extent to which their formations were being intercepted.

When the Battle of France showed all the signs of being lost, it was Dowding who first faced up to Churchill and flatly refused to allow any more squadrons to be sacrificed in that contest. Even so, with all the squadrons available in late August 1940, at the height of the Battle of Britain, and with the enemy’s continued attacks on our radar installations and airfields, the outcome hung in the balance. At that point, some bombs fell in central London and it was then decided to bomb Berlin in retaliation and to serve as a morale booster at home. Fortuitously, this caused Goering, who had boasted that Berlin would never be attacked, to switch, with Hitler’s agreement, the main weight of attack to London. This crucial misjudgement allowed our fighter stations to recover. Within weeks, the tide in the air battle had been turned and Hitler decided to postpone the invasion indefinitely. By early the next year he finally resolved to turn against Russia regardless of his failure to overcome the United Kingdom.

The Battle of Britain was an attempt to defeat the will of the British people, and the whole country played a part in defeating the German plan.

While the RAF fighter pilots were the tip of the sword, we must also acknowledge the contributions of many others, whether serving in the RAF or elsewhere. The nation has much to ‘owe’ to those bomber crews who battled all the way to Berlin in their comparatively slow aircraft, and who also played a vital part with their attacks on the invasion ports and enemy shipping. I cannot praise them too highly. Nor must we forget other services – Anti-Aircraft Command, the Observer Corps and Civil Defence as well as Coastal Command and the Royal Navy, with its flotilla of light vessels which were ever vigilant in eastern and southern ports, ready to counter the threat of invasion ships and barges. But, in all, the key was ‘command of the air’. We were short of pilots from the start, but fortunately, we were never short of aircraft thanks not only to the aircraft factories but also to the Civil Repair Organisation and RAF Repair Depots, the latter, between them, turning out 60 aircraft per week. It was not just the ‘Few’, it was the ‘Many’.

As to the conduct of the Battle, day to day operations were in the hands of the 11 Group Commander with the other Groups playing a supporting role as necessary. Dowding at Fighter Command provided the means and the strategy, while the A.O.C. 11 Group, Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, fought and won the critical battle. For this he deserves the highest praise. However, it must be admitted that this subordination of other Groups to 11 Group was the cause of some bad feeling and friction between 11 and 12 Groups, particularly over tactics.

Much has been written over the years about ‘Big Wing’ tactics, leading in some cases to harsh criticism of the parts played by Air Vice Marshal Leigh-Mallory and in particular Douglas Bader. However, we have had available for some time the relevant Air Ministry and Fighter Command files of September/October 1940 covering operations during the battle, and also the reports submitted to Dowding by both Park and Leigh-Mallory. These subsequently were passed to the Air Ministry, and here I find that some authors have not only been selective in their material, but also biased in their interpretations. For example Leigh-Mallory’s first report in September 1940 on Wing Operations was forwarded by Fighter Command to the Air Ministry with the final comment ‘A.O.C. 12 Group is working on the right lines in organising his operations in strength’, while in Park’s report it is clear that 11 Group squadrons operated in a ‘Wing’ of three squadrons on a number of occasions when conditions and warning time were favourable, and in fact he issued at least two instructions to his units covering the methods and tactics of ‘Wing’ operations.

Clearly Park was unhappy, to say the least, with the use the Air Ministry made of the various reports, and he had good reason to be, but there is no evidence that Fighter Command were critical of the way Leigh-Mallory was operating his squadrons, if anything the reverse is true.

It was as a result of these Group Commanders’ reports that Air Vice Marshal Sholto Douglas (Deputy Chief of Air Staff) began to take an interest, and set up the now famous meeting in October to ‘Discuss future Fighter Tactics’. Douglas Bader only spoke once at that meeting, when invited by the Chairman; but Leigh-Mallory, in bringing him along, had put him in a mighty privileged position for a Squadron Leader. Frankly he had no business to do it, as it was bound to invite comment as to his motives and, of course, upset Park, whose Squadron Commanders in 11 Group had borne the brunt of the battle. Even so, when the minutes of the meeting were circulated, Dowding and Leigh-Mallory had relatively minor amendments. Keith Park submitted a copy of the notes he used at the meeting and requested that they be attached to the minutes, Douglas refused. Here I must add that I know from many conversations I had with Douglas Bader in his lifetime that he had the highest regard for both Keith Park and Dowding. Indeed, he gave the address at the Service of Thanksgiving for the life of Park and he wrote the following tribute to Dowding: – ‘To the fighter pilots of 1940 Dowding was the father figure. Seldom seen, many pilots did not know even how he looked. Nevertheless we knew he was there in Fighter Command minding our affairs, so all was well. We held him in esteem which after the war became affection. We read about him; how he had fought the Treasury to get hard runways built on grass airfields, waterlogged and unusable in winter; how he had insisted on bullet-proof windscreens in our Hurricanes and Spitfires. After the war at Battle of Britain dinners we actually saw him and spoke with him. We were proud that he had chosen to be known as Lord Dowding of Bentley Priory – our home from home – Headquarters, Fighter Command. At last we felt this gruff, withdrawn, inarticulate ‘Stuffy’ Dowding really had become one of us. We thought it a bad show that he had not been made a Marshal of the Royal Air Force.’

As I look back now to those days as a young, very junior officer flying daily alongside Douglas Bader, I realise how fortunate I was. It was a never-to-be-forgotten experience which materially shaped my subsequent career. I believe this book will appeal to most. It covers every aspect – pilots, aircraft and equipment – in great detail, and will contribute to our understanding of this key period in our nation’s history.

PRELUDE TO BATTLE

At 0445hrs on September 1, 1939, the first shots of World War II were fired when the Luftwaffe attacked Poland. An hour later German ground forces crossed the Polish frontier. A new style of warfare devised by Germany had been unleashed: der Blitzkrieg, the lightning war, synchronising simultaneous massive assaults by dive bombers and tanks.

Why was the German invasion of Poland of consequence to France and Britain? Because on April 1, 1939, Britain and France had guaranteed to defend Poland against any threat by Germany.

On August 24, 1939, Germany had signed a non-aggression pact with Russia. The British General Staff was sceptical about this, knowing that Nazism was the avowed enemy of Communism and expecting Hitler to turn on his new ally as soon as he felt strong enough. The British made two appreciations of the situation. One was that, as Hitler had no strategic need to enter Poland, he would, faced with the certainty of British and French intervention, attack the Ukraine as a first step towards the conquest of Russia. The other was that Hitler would take on Poland, France and Britain, that the first two would quickly succumb, that Britain was his main objective and he would immediately order the Luftwaffe to obliterate London and its docks, then send his Army to invade England.

In fact, Hitler did not expect to have to fight the British at all. Joachim von Ribbentrop, who had been Ambassador in London before becoming Foreign Minister in 1938, had constantly assured him that the British were effete and would not go to war. Hitler himself thought that Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister, had made an empty promise to Poland merely to frighten Germany. The British Government had been pusillanimous and appeasing throughout Hitler’s time as Chancellor and dictator. He had easily deceived Chamberlain at their meetings in Munich in September 1938. All this made him certain that once again the British Cabinet would prove too cowardly to face war with Germany.

Immediately on the invasion of Poland, the British and French Governments demanded German withdrawal. Hitler ignored them. The next day there were frantic talks in Paris and London. As usual, Chamberlain and his Ministers took a passive line. The French Government showed no more courage or sense of honour than the British. But the British Parliament felt differently and prevailed on the Government to give Germany an ultimatum. France followed suit. At 1100hrs on September 3, 1939, Britain declared war, and France did so at 1700hrs. Thus, while the Germans were conquering Poland, a British Expeditionary Force and units of the RAF were establishing themselves in France.

■ The Defeat of Poland

In anticipating the German conquest of Poland, Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the German Army, to whom Hitler had given responsibility for the campaign, summarised his objective as ‘To anticipate an orderly mobilisation and concentration of the Polish Army and to destroy the main bulk of it west of the Vistula-Narev line by concentric attacks from Silesia, Pomerania and East Prussia’. The plan was intended to squeeze most of the Army in a pincer-grip and prevent it from escaping over the Vistula. This meant that the Luftwaffe must first establish air superiority. On a vast scale, never attempted before, bombers would disrupt road and rail traffic deep in Poland; and, the more significant tactic, bombers and fighters would maintain constant bombing and strafing of ground troops.

The latter is invariably described as a total innovation. It was nothing of the sort. Britain’s Royal Flying Corps introduced it on the Somme in 1916 with terrifying effect described by a German infantryman, who wrote home: ‘One can hardly calculate how much additional loss of life and strain on the nerves this cost us.’ By 1918 it was standard practice on both sides, for which purpose-designed aircraft were built. What the Germans did do, with their traditional thoroughness, was to develop air-to-ground attack to its ultimate potential.

The resolution of these and all the other associated problems, by preliminary theory and by practical experience in Poland, was the rehearsal for what was to follow eight months later in Belgium, Holland and France; and would have been inflicted on the British if RAF Fighter Command had not won the Battle of Britain. The first purpose, to destroy the Polish Air Force, if possible on the ground, also foreshadowed Goering’s design in July, August, September and October 1940.

The Polish General Staff was old-fashioned, the Army was inadequately equipped and poorly deployed to defend the 1,750 miles (2,815km) of frontier adjoining East Prussia and Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia. No defences had been built, the armoured force was small, and the cavalry was the Army’s pride. The Poles, with their traditional dash, relied on the efficacy of counter-attacks. When the German tanks rolled across the Polish plains they were met by cavalry charges.

The Germans sent in two Army Groups: one comprising the Third and Fourth Armies, the other the Eighth, Tenth and Fourteenth.

The Luftwaffe Order of Battle for this campaign numbered 648 bombers, 219 dive bombers, 210 single- and twin-engine fighters, 30 ground attack aircraft and 474 reconnaissance and transport types.

The Polish Air Force was organised in regiments, wings and squadrons. The strength on September 1, 1939, was 159 PZL P7 and PZL P11 single-seat fighters, all three to seven years old, 154 PZL 37 and PZL 23B bombers and light bomber/recce aircraft capable of offensive operations, and 84 observation aircraft.

German intelligence mistakenly estimated the Polish Air Force frontline strength as more than 900, including 150 bombers, 315 fighters, 325 reconnaissance, 100 liaison and 50 naval aircraft.

The Polish combat aircraft were nowhere near as capable as those of the Luftwaffe. From the Luftwaffe strength given above and the specification of its aircraft given in a later chapter, it is clear that the Polish Air Force was at a huge disadvantage in numbers and in aircraft performance and armament.

The Polish War Plan and General Directive for Air Operations, issued on July 28, 1939, laid down that fighter squadrons were to be used as an integral part of the Armies, with the exception of the Pursuit Brigade, consisting of five squadrons, which was to be under the control of the Supreme Commander of the Polish Forces. The tasks for the Army fighter squadrons (known as the Army Air Force) were: interception of enemy aircraft over the Army sector, air cover of Polish aircraft operating over the Army sector, and in critical situations, air attacks on enemy ground forces. The task of the Pursuit Brigade was air defence of the country.

The eight squadrons operating with the four Armies covered large sectors but had no radio, and therefore no co-operation with, or information from, the ground when airborne. Enemy activity was so intense, however, that most take-offs were followed by combat. The rapid advance of the German Army and the Luftwaffe’s attacks on airfields necessitated frequent changes of base. Heavy losses of aircrew and aircraft were suffered on the ground and in the air.

After 12 days the Army Air Force ceased to operate effectively and was withdrawn to join the remnants of the Pursuit Brigade. There was one exception: the Poznan Army Wing, commanded by Major M. Mumler, fought until September 16, 1939. It shot down 31 enemy aircraft, lost two pilots killed, four wounded and six missing, and lost all but one of its aircraft. This last, flown by the commanding officer, landed in Romania on September 18 – all that remained of an initial strength of 22.

The Pursuit Brigade was based on airfields near Warsaw to defend the capital and its environs. Eight radio stations provided a means of communication and control, although the radio range was only 9 to 12 miles (15 to 20km). The Warsaw surveillance centre provided information on the enemy. On September 7 the Brigade, with 16 serviceable aircraft, was moved to the Lublin area, to be joined later by the surviving pilots and aircraft of the Army squadrons. The combined fighter force, short of fuel and deprived of adequate communication, shot down only five enemy aircraft between September 7 and 17, after which the Polish Air Force ceased to operate. The Polish Army fought on until October 3.

It is customary to dismiss the performance of the Polish Air Force with the statement that it was wiped out on the ground before it could put up a fight. As the foregoing proves, this is wildly inaccurate and a calumny on brave men who died disproving it, and on those who survived to fight on in the RAF.

The Luftwaffe suffered 285 aircraft destroyed and 279 severely damaged; 189 Luftwaffe aircrew were killed, 224 missing and 126 wounded.

Out of 435 aircraft engaged, the Polish Air Force lost 327 from all causes, of which 264 were by direct enemy action, destroyed in combat or on the ground; at least 33 were shot down by their own anti-aircraft gun fire and 116 escaped to Romania. Aircrew killed and missing numbered at least 234.

The experience of 18 days’ hard air fighting contributed nothing to help the RAF in the Battle of Britain. The German aircraft destroyed and aircrew killed or disabled were more than replaced by then. The disparity between the quality and quantity of the Polish and British fighters was obvious: the Polish PZL P7s and P11s had been at a crippling disadvantage, but if Germany had attacked Britain then, Hurricanes and Spitfires would have mauled the Luftwaffe.

Although scores of Polish fighter pilots managed to reach France and Britain and were interrogated by French and British intelligence officers, no conclusions were drawn from the fact that the Luftwaffe fighter formation based on loose pairs was obviously more effective than the conventional threes of the Polish and French Air Forces, and the RAF. Nothing was deduced about how defending fighters should deal with formations of 50 to 100 bombers accompanied by an equally large fighter escort, or the best technique for shooting down dive bombers.

The Luftwaffe, on the contrary, benefited from a tremendous boost to its morale, the satisfaction of knowing that it had made devastatingly effective use of what it had learned in the Spanish Civil War, and the combat knowledge gained by its pilots and crews.

■ The Battle of France

At the time of France’s declaration of war against Germany, her air force was poorly equipped to conduct either a defensive or an offensive campaign. Despite the warnings of General Vuillemin, the Air Force Chief of Staff, and Captain Stehlin, the Air Attaché in Berlin, the French High Command had refused in the 1930s to recognise Germany’s aerial rearmament. No pressure was put on indigenous aircraft manufacturers to design and build fighters or bombers that would meet realistic modern requirements. Little air-to-air firing was done; gunnery training was almost totally limited to camera gun practice. Fighter pilots were trained to make beam attacks ending with a full deflection firing pass at 820ft (250m). These were to prove mostly abortive against the Luftwaffe because the French aircraft lacked sufficient performance.

The total fighter strength of aircraft considered to have a performance capable of taking on the Messerschmitt 109 was 250 Morane 405/406 and 120 Curtiss H75 (US-supplied Curtiss P-36). The bomber and reconnaissance strength consisted of 120 Bloch 151/152, 85 Potez 630 and 205 Potez 631.

Regular officer pilots were trained at l’Ecole de l’Air and NCOs at l’Ecole d’Istres. Pilots and observers on the Reserve were trained during their compulsory military service. Pilot candidates aged 18 could, on passing an examination, be trained initially as civilians at a civil flying school. They would then sign on for three years and complete their training at Istres, after which they joined a squadron. At the end of the contract period they were put on the Reserve, in which there were two classes. Class A reservists were assigned to a squadron, with which they did about 10 hours’ flying a year. Class B did no continuation flying and were sent on a refresher course in the event of mobilisation.

The Organisation of France’s Air Force, l’Armée de l’Air, in 1939 was: groupements comprising several groupes; escadres comprising two groupes (until May 1939, when some were increased to three); groupes comprising two escadrilles (squadrons); escadrilles comprising three patronilles (patrols) of three aircraft in each.

In addition, there was one unit similar to a British Auxiliary Air Force squadron: l’Escadrille de Paris, based at Villacoublay.

The normal aircraft establishment for a groupe was 25, but for those flying the Curtiss it was 30. The pilot establishment for all groupes was 30.

On August 28, 1939, fighters were based as follows: at Etampes: 1st Escadre, comprising two groupes of obsolescent Dewoitine 510; Escadrille 1/13, night fighter, equipped with Potez 631. At Chartres: 2nd Escadre, three groupes of Morane 406; 6th Escadre, two groupes of Morane 406. At Dijon: 3rd Escadre, three groupes of Morane 406; 7th Escadre, two groupes of Morane 406. At Reims: 4th Escadre, two groupes of Curtiss H75; 5th Escadre, two groupes of Curtiss H75; Escadrille 2/13, night fighter equipped with Potez 631. At Marignane: 8th Escadre, comprising two groupes, one with Dewoitine 510, the other with Potez 631.

By August 1939, these were dispersed on active service aerodromes that were mostly bare fields among woods or forests far from a town. The aircraft were kept in the open air. The pilots were often billeted with civilians if a village were near enough. The ground troops lived in barns and slept on straw.

The standard fighter formation was three aircraft, with the leader in the centre and his wing men laterally separated by 220 yards (200m) from him, one 55 yards (50m) below him, the up-sun aircraft taking the higher position.

The control and reporting system was, by British standards, ramshackle. Warning of hostile aircraft was based on the Système de Guet, the Look-Out System, similar to the Observer Corps in Britain but less reliably served by the telephone lines on which it depended. This was weakly supported by a radio method of detection, détection électromagnétique or D.E.M., consisting of a chain of alternate transmitters and receivers. These gave a rough plan position of aircraft by observations on the bearing produced between the direct wave from the transmitter to the receiver and the reflected wave from the aircraft. It had a range of approximately 50km and did not give satisfactory results on more than one aircraft.

Fighter control was handicapped by poor radio equipment. Aircraft sets needed frequent retuning in the air. Their air-to-ground range was 93 miles (150km) at heights above 3,280ft (1,000m), and air-to-air 31 miles (50km)

This small Regular air force and inchoate Reserve, with its scanty supply of modern fighters and enduring hard living conditions, nevertheless entered the war with high morale.

The entire nation felt secure behind the Maginot Line, the most impressive fortification ever built, consisting of three lines of reinforced concrete outposts, blockhouses and forts with underground arsenals, living quarters and hospitals. Defended by enormous artillery pieces and tens of thousands of infantry, it stretched along the German frontier from Belgium to Switzerland. The French believed it was impregnable.

■ The British Expeditionary Force

The first units of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), under the command of Field Marshal Lord Gort, began to land in France on September 10, 1939, Two RAF formations had preceded them. The Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) was commanded by Air Vice Marshal P. H. L. Playfair, CB, CVO, MC, who had joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1912 from the Royal Artillery and won his Military Cross in France during World War I. His headquarters was near Reims, around which his squadrons were based. Their task was to work with the French Army along the German frontier. The Air Component of the BEF, under Air Vice Marshal C. H. B. Blount, CB, OBE, MC, with his headquarters near Arras, was based in the Pas de Calais. Its function was to operate with the BEF, which went into the line along the Belgian frontier, and to patrol Channel convoys. Blount, who transferred from the Surreys to the RFC in 1913, had also won his gallantry decoration in the Great War, when commanding No. 34 Squadron in France and Italy.

The Advanced Air Striking Force consisted of 10 bomber and two fighter squadrons. Nos. 12, 15, 40, 88, 103, 105, 142, 150, 218 and 226 flew the Fairey Battle. This was an obsolescent three-seater type with a single 1,030hp Rolls-Royce Merlin engine and armed with one fixed .303in Browning gun forward and one .303in Vickers K aft. Its maximum speed was 241 mph (388km/h) at 13,000ft (3,960m) and its ceiling 23,500ft (7,160m). The bombload was 1,000lb (453kg). Nos. 85 and 87 had Hurricanes, whose specification is given elsewhere. The Battles landed in France on September 1 and the Hurricanes on the 7th.

The Air Component, whose records were almost totally destroyed during the hasty retreat of the British forces in June 1940, comprised the following: Four corps squadrons, whose function was army cooperation: Nos. 2, 4, 13 and 26, flying Lysanders. These were two-seater, single-engined, high-wing monoplanes with 890hp Bristol Mercury XII engines and armed with two fixed .303in Brownings firing forward and one .303in Vickers or Lewis in the rear cockpit firing aft; maximum speed 219mph (352km/h) at 10,000ft (3,050m); ceiling 26,000ft (7,925m).

Four army squadrons. Nos. 18, 53, 57, 59, flying Blenheims, whose specification is given elsewhere.

Six fighter squadrons. Those equipped with Hurricanes were Nos. 1, 17, 85 and 87. Those with Gladiators were 607 (County of Durham) and 615 (County of Surrey), both of the Auxiliary Air Force.

None of the 12 airfields designated for the Air Component was in the area allotted to the British Army, which was supposed to supply them with rations, tents, fuel, pay, works, postal service, furniture, billets, etc. The French Army proved helpful and supplied rations, wine and petrol. All these airfields were covered in clover, not grass, and would become soggy and non-operational in wet weather. None had hangars or had been provided with any other resources. The RAF did not know this before-hand, because Britain had made a gentlemen’s agreement with France not to do any intelligence studies there.

The British Army came to the rescue of the Air Component in the person of an officer on Gort’s staff. He was Brigadier Appleyard of the Territorial Army, who was chief engineer of a major road-construction company and undertook to provide 20 proper airfields by the spring. He returned to England and visited the managing directors of his own employers and four other leading road contractors. With their wholehearted cooperation he raised five companies for the Royal Engineers, each bearing the name of the firm that it represented and by which it was provided with all the necessary equipment needed for earth moving, road construction and the building of accommodation. Having been vested with virtual omnipotence in achieving his objective, he obtained commissions in the rank of major for company directors and captain for managers. Foremen became instant sergeants and charge hands were enlisted as corporals. Uniforms were supplied immediately. Swiftly they were in France, putting up huts for themselves and sowing grass seed on the ploughland that had been selected for conversion (it is appropriate to confirm here that by the spring they had indeed rolled the new grass and laid down concrete runways on nearly all their 20 sites.)

The war began with a period of comparative inactivity that was, in comparison with the eventual Blitzkrieg that came in 1940, retrospectively known as the Sitzkrieg. The French refer to it as La Drôle de Guerre – The Joke War. The Allied land and air forces stagnated. Their armies patrolled in front of the Maginot Line and fought occasional skirmishes. Their air forces were forbidden to bomb Germany for fear of reprisals. The Luftwaffe was under the same restrictions over Britain and France. The BEF’s artillery did gunnery practice for which the Air Component’s Lysanders spotted as they used to on Salisbury Plain. They also did some close reconnaissance and photography. The Blenheims were interestingly employed on photographic reconnaissance over Germany.

The only sector of the Franco-German frontier across which the Allies or the Germans could attack was the 90 miles (146km) between the Rhine and the Moselle. Well within her own territory, Germany had built strong defences, the Siegfried Line or West Wall. The Blenheims photographed the whole of it, as well as more distant objectives. Nos. 1 and 73 Squadrons filled their time with convoy patrols and the normal practice flying.

The RAF squadrons based at home had meanwhile been more active than those in France. On the night of September 3, Whitley bombers flew the first of many leaflet raids – codenamed Nickel – and dropped six million copies of an exhortation to Germany to abandon the war. Not only was the penalty for reading them severe, which ensured that few would be picked up, but also this was psychologically an absurd time at which to spread propaganda. German morale was at its height with the invasion of Poland going so much in Germany’s favour. The time to spread propaganda is when one has the upper hand and the enemy’s resolve is wilting. Casualties among the crews who flew these sorties were, like those of the crews who carried bombs across the North Sea or made daylight sorties in Battles and Blenheims from France, particularly sad in their wastefulness. All three activities were futile. At Air Ministry and in Bomber Command HQ was a theory that casualties on leaflet raids could have been heavier, because the enemy hesitated to betray the siting of his flak and searchlights when he knew that neither bombing nor photography was their purpose. This was not shared by the men who actually did the job. What was true was that the elementary radar was of scant help in controlling night fighters which were therefore less lethal than they might have been.

On September 1 President Roosevelt of the USA had appealed to the German and Polish Governments to limit bombing to legitimate military objectives. On the same date Hitler said in the Reichstag: ‘I will not war against women and children. I have ordered my air force to restrict itself to attacks on military objectives.’ On that very day, the Luftwaffe bombed 60 towns and villages in Poland. On September 3 Hitler replied to Roosevelt: ‘It is a precept of humanity in all circumstances to avoid bombing non-military objectives, which corresponds entirely with my own attitude and has always been advocated by me.’ On September 13 he attempted to justify his savage bombing of Polish civilians by claiming that it was legitimate because the Polish Government had incited its citizens to fight the Germans as franc-tireurs.

Although bombing the German mainland was forbidden and German bombers were under orders not to attack mainland Britain or France, shipping in port was a permitted target. Flying Officer A. MacPherson of No. 139 (Blenheim) Squadron flew a reconnaissance off Wilhelmshaven on September 3 but his wireless report was too distorted by atmospherics to read. On September 4 he took off again at 0835hrs to repeat the sortie. Despite low cloud and rain squalls he obtained photographs of ships in Brunsbüttel, Wilhelmshaven and the Schilling Roads, including the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and training cruiser Emden. Once more his message was unreadable. After he reported verbally on landing, 15 Blenheims of Nos. 109, 110 and 139 Squadrons set out to bomb Wilhelmshaven and 14 Wellingtons from Nos. 9 and 149 Squadrons to bomb two battleships in Brunsbüttel.

With cloud base at 500ft (150m), only three Blenheims of 110 were able to attack. One hit the Admiral Scheer but the 500lb (227kg) bombs were too light for the task and the 11-second fuse did not detonate it until after the bomb had bounced off the warship’s deck. Another Blenheim crashed on the Emden, fatally for the crew. Only one Blenheim of No. 107 Squadron returned and there is no record of any hits. No. 139 Squadron could not find its target in the adverse weather and returned unscathed without having bombed anything. None of the Wellingtons claimed hits. Most failed to find the target or turned back early because of bad weather. Two did not return. All aircraft met accurate and heavy flak and the Wellingtons were attacked by Bf 109s.

On September 29, 12 Hampdens of Nos. 61 and 144 Squadrons took off for Heligoland and the Frisian Islands. One turned back. Six saw two destroyers, which three attacked unsuccessfully and three could not get in position to attack. Five were attacked by Bf 109s and all were shot down.

These heavy losses did not shake the sacred Bomber Command axiom that a section of three bombers in close formation in broad daylight had the combined defensive fire power to drive off any number of heavily armed attacking fighters.

In France, by mid-September two Blenheim squadrons, Nos. 114 and 139, had joined the AASF. From the outset both the Allies and Gemany had been making several daily photo reconnaissance sorties. While the Germans evaded anti-aircraft fire and fighters, the Battles and Blenheims constantly suffered casualties from both. Flak over Germany was heavy and accurate. The information gained was not worth the loss of one or two Blenheims day by day, so daylight sorties stopped and night reconaissaissance began. Taking off by the light of six blue glim lamps at 200-yard (183m) intervals was inherently hazardous. Over Germany not only were German searchlight crews highly efficient but, in order to take photographs, flares were used which attracted flak and night fighters. Heavy losses continued.

It was No. 1 Squadron that scored the first British success, on October 30, a sunny day with no low cloud. Flying Officer P. W. ‘Boy’ Mould, who had joined as a Halton apprentice in 1934 and been selected for Cranwell in 1937, had barely refuelled after a patrol when a Dornier 17 flew high over the airfield. He took off without awaiting orders, caught up with the Dornier at 18,000ft (5,485m) and attacked from astern. It caught fire and spun vertically until it crashed into the ground.

On October 31 a member of 73 Squadron who was destined to become the best-known pilot in the Battle of France destroyed his first enemy aircraft, Flying Officer Edgar James Kain, known as Cobber, was a New Zealander who had come to England in 1936 to join the RAF. He gave an acrobatic display at the Empire Air Day show in 1938.

On patrol in a Hurricane he saw anti-aircraft shells bursting and headed towards them. At 27,000ft (8,230m) he intercepted a Do 17 and fired at it. Its port engine began to smoke and its rear gunner returned his fire while its pilot took evasive action. Kain gave the Dornier a long burst with the remainder of his 14.8 seconds’-worth of ammunition and it fell into a vertical dive. His Hurricane could not keep up with it and he pulled out at 400mph (643km/h). The Dornier crashed in a village street. This combat set an altitude record for air fighting. On November 23 Kain shot down another Do 17.

On November 7 Germany’s assault on the Low Countries was postponed on account of the weather. It was put off 13 times more and the last definite date Hitler chose was January 16, 1940.

The best day of 1939 for the RAF fighters was November 23, when several enemy aircraft were plotted on the map in the Operations Rooms of Nos. 1 and 73 Squadrons, and Hurricanes were scrambled. Sqn Ldr ‘Bull’ Halahan and Flying Officer ‘Hilly’ Brown, a Canadian, intercepted a Do 17 and shot it down in flames. A section led by Flt Lt ‘Johnny’ Walker caught an He 111, which they set on fire. While it was going down out of control a formation of Moranes came dashing in, one of which collided with Sgt ‘Darky’ Clowes’s Hurricane and tore off an elevator and half the rudder. The French pilot’s aeroplane was even more badly damaged and he baled out. Clowes landed at 120mph (193km/h), overshot and nosed in, but was unhurt. Another section of No. 1 Squadron, led by Flt Lt ‘Pussy’ Palmer, attacked a Do 17, set it alight and saw the rear gunner and navigator bale out. Palmer flew alongside to ensure that the pilot was dead. He found out that the German was not when the bomber swerved onto his tail and riddled his Hurricane with 43 bullets. His engine stopped with coolant smoke issuing from it but he made a force-landing, while FO Kilmartin and Soper resumed shooting at the Dornier, which in turn force-landed with both engines on fire. The German pilot waved at them as they circled the wreckage. No. 73 Squadron destroyed three Do 17s, one of which fell to Cobber Kain.

The first Czech pilots arrived in France after long circuitous journeys and were distributed among the Morane groupes. They were soon followed by Poles, who were given their own groupe, No 1/45, under the command of Major Kepinski and equipped with Moranes.

By the end of the month an exceptionally severe winter had the Continent in its grip. On December 10 the temperature fell to minus 26 degrees Fahrenheit (-32 degrees Centigrade) and on the 12th to minus 29. Air activity by both sides greatly diminished. It would be March before the Luftwaffe resumed large-scale operations.

Throughout the four months from the outbreak of war to the end of 1939, Coastal Command, which attracted the least attention from the press, had been going about its business over the Atlantic and the North Sea, achieving successes that indirectly contributed to the RAF’s victory in the Battle of Britain. Oil, petrol and raw materials of every kind were as necessary to maintain Fighter Command’s operational strength as were aircraft and pilots. Coastal Command constantly made reconnaissance sorties in search of enemy warships and, with the Royal Navy, protected merchant shipping bound for Britain and limited the depredations of the U-boats. In the first fortnight of the war the enemy sank 21 British merchant ships with a total tonnage of 122,843. During the two weeks ending October 9, 1939, only 5,809 tons of shipping were lost, and on November 14 it was announced that 3,070 ships had been convoyed with a loss of only seven.

General Gamelin, the French Commander-in-Chief, had been insisting that there should be an RAF chief responsible for both the AASF and the Air Component of the BEF. Accordingly, on January 9, 1940, Air Marshal Sir Arthur Barratt was appointed Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, British Air Forces in France. He made his HQ at Coulommiers, where the French Air Force C-in-C had his. Barratt, known as ‘Ugly’, had adequate credentials. He served in France during the Great War and immediately before his new appointment was Principal RAF Liaison Officer with the French forces.

On January 16, Hitler postponed his advance through the Low Countries until the spring.

The scale of air fighting over France began to increase in March 1940. Most combats developed to the same pattern: British and French fighters patrolling above 20,000ft (6,010m), seeking German bombers escorted by fighters, the opposing fighters each striving to have the height advantage at the moment of interception.

Kain made his third kill, a Bf 109, on March 3, but his Hurricane was hit and he had to bale out. He got his fourth, another 109, on March 26, but his aircraft was set on fire. Despite this he destroyed one more 109 before baling out. His score of five qualified him as an ‘Ace’, the first Allied pilot of this war to achieve this, and he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. He was now the most famous pilot in the RAF, as well-known to the public as ‘Sailor’ Malan, Douglas Bader and Bob Stanford Tuck were destined to become.

Another Commonwealth pilot who had spectacular success in France was an Australian, Flying Officer Leslie Clisby of No. 1 Squadron. He opened his score with a Bf 110 on March 31. Flying Officer Newell ‘Fanny’ Orton, who had been in No. 73 Squadron since 1937, also shot down a lot of Germans, starting with two Bf 109s on March 26.

In April the pace, like the weather, became warmer in patches interspersed with rain that hampered flying. Clisby bagged a Bf 109 on April 1 and another next day. Peter ‘Johnny’ Walker, commanding A Flight of No. 1 Squadron, had joined the Service in 1935 and performed in the squadron aerobatic team at the Hendon Air Pageant in 1937. Having shot down a Bf 110 on March 29 he added a Bf 109 on April 20. Orton got a Ju 88 on April 8 and on the 21st a 109 and a 110. ‘Boy’ Mould had accounted for a 110 on March 31, and on April 1 he shot down another. Sergeant Harold ‘Ginger’ Paul of No. 743 Squadron made his first kill on April 21, a Bf 109. Flt Lt Peter Prosser Hanks, known by his second forename, commander of B Flight, No. 1 Squadron, another member of the aerobatic team, had sent a 110 down on March 31 and got an He 111 on April 20.

■ The Invasion of Scandinavia

While the Allies awaited Hitler’s spring offensive in Western Europe, Germany carried out a lightning invasion of Denmark and Norway on April 9. Two divisions under General Kaupitsch and an air force of some 500 combat aircraft, and nearly 600 transports, made the assault on both countries simultaneously. Both victims of the Nazis’ latest aggression had only token air forces that were given no time to make even a gesture in defence of their countries. The Danish Army numbered only 15,000. Resistance was pointless.

At 0530hrs the Ju 52 transports carrying paratroops took off, but the approaches to both Oslo and Stavanger were obscured by fog from sea level to 2,000ft (610m). Low-level flight was impossible, and from above cloud the aerodromes on which the paratroops were to drop and the aircraft to land could not be seen. The first objectives of the paratroops were the airfields at Aalborg East and Aalborg West in Denmark, and Oslo-Fornebu and Stavanger-Sola in Norway. The first two were attacked at 0700hrs. Twelve hours later Copenhagen had been taken and the conquest of Denmark completed.

As with the Polish invasion, writers about this operation habitually state that the Norwegian Air Force, which comprised about 100 aeroplanes, nearly all fighters and reconnaissance types, was obliterated on the ground before it could put up a fight. That is not true either. While the Ju 52s were trying to land at Fornebu, Oberleutant Hansen, commanding I/ZG76 (Bf 110s), was giving them fighter cover. At 0838hrs his eight 110s were attacked out of the sun by nine Norwegian Gloster Gladiators, which shot down two of them.

The German landings by air and sea went ahead despite delays caused by weather, in the face of a brave defence by the Norwegian Army, Navy and what was left of the Air Force after the swift capture of the airfields. The Luftwaffe occupied the airfields and provided all the forms of air support essential for success in modern warfare. The fighting spread throughout the country.

Both Britain and France sent expeditionary forces but, to quote the archives, ‘With regard to air forces it was decided that none should accompany the expedition in the first instance.’ Critics have always deplored this as indicative of the backwardness of military thinking in Britain and France. Admittedly, the General Staffs in both countries were still imbued with out-dated notions about the use of air power, but one wonders where their critics suppose the aircraft could have come from? Neither the RAF nor l’Armée de l’Air could spare an adequate number of fighters from home defence. The French bombers were too poor in performance, bombload and armament to be effective or to protect themselves. From the first day of this campaign RAF Bomber and Coastal Commands were doing the best they could by sparing aircraft from other tasks to reconnoitre the Norwegian coast, to sow mines and to bomb. Even long-range Blenheim fighters were sent all the way to hunt enemy aircraft in the region of Stavanger and Bergen. Bombing raids were carried out against the two German-occupied airfields at Aalborg, Denmark.

On April 15, Britain’s 24th Guards Brigade arrived at Harstad. Next day, 146 Brigade landed at Namsos. On the 18th, 148 Brigade landed at Andalsnes and part of the 5th Demi-Brigade Chasseurs Alpins landed at Namsos.

On April 21, No. 263 (Gladiator) Squadron sailed for Norway in the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious. None of its 18 pilots had ever done a deck landing or take-off, so Fleet Air Arm pilots flew the 18 Gladiators on board for them. At 1700hrs on April 24, 50 miles (80km) to seaward of Trondheim, the RAF pilots flew them off, each flight of nine led by a naval Skua two-seater, which carried a navigator, to guide them in the threatening weather. By 1900hrs all the fighters had landed on the frozen Lake Lesjaskog. During the night the carburettors and controls of the aircraft froze. The only way to warm an engine was to run it, which was done with some aircraft in readiness for dawn. The ground crews were not at full strength, so pilots had to share in guarding the aircraft.

At 0445hrs on the 25th two Gladiators took off on patrol and shot down an He 115. At 0745hrs the Luftwaffe began dive-bombing and strafing the lake. By 1230hrs bombs had destroyed eight Gladiators, four of which had not even flown. At 1305hrs bombs destroyed four aircraft and wounded three pilots. All day, aircraft took off whenever they could, harassed by bombers. There were several combats and two He 111s were destroyed. By the evening, 11 Gladiators had been burned out and two, beyond repair, were set alight. The squadron moved to Setnesmoen. On the 26th only three Gladiators were left. Next day there was none. The squadron had flown 49 sorties and made 37 attacks against enemy aircraft. Six victories were confirmed by the finding of wreckage, and eight claims remained unconfirmed. On April 28 the squadron personnel embarked in a cargo vessel and arrived in England on May 1.

On May 20 the re-formed No. 263 Squadron flew their new Gladiators off the aircraft carrier HMS Furious, 100 miles (160km) from Bardufoss, led by two Fleet Air Arm torpedo/reconnaissance Swordfish. In low cloud and mist, two fighters crashed, killing one pilot and severely injuring the other. On the 21st the squadron flew 40 standing patrols. On the 22nd it flew 54 sorties. One pilot was killed in action against He 111s. An airfield had been prepared at Bodø with shelters and underground accommodation. On May 26 three Gladiators began operating from there.

No. 46 (Hurricane) Squadron had been sent to join No. 263. On May 26 the new arrivals took off in their Hurricanes from HMS Glorious, to attempt a landing on the Skånland airstrip where a wire mesh runway had been laid. Ten landed but sank four inches (10cm) through the soft ground, and two pitched onto their noses. The remaining eight were diverted to Bardufoss. Next day another Hurricane stood on its nose at Skånland, so the remaining seven also moved to Bardufoss.

In bad weather and under heavy bombing, the two squadrons slogged on until June 7. By then 263 had flown 389 sorties over 12 days, been in combat 69 times and claimed 26 successes. No. 46 had also operated on 12 days to take part in 26 fights and claim 11 kills and eight probables. No. 263 landed their remaining eight Gladiators on Glorious during June 7. No. 46, none of whom had yet attempted a deck landing, followed with their 10 Hurricanes.

On June 8 the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst sank Glorious with 1,474 of her ship’s company and 41 officers and men of the RAF. Only two of the pilots who had fought so bravely and endured so much hardship in Norway survived.

This brief campaign contributed nothing that directly was of any help to Fighter Command in the Battle of Britain. On the contrary, it deprived the RAF of 30 experienced fighter pilots and 36 aircraft. The operating conditions bore no resemblance to those in the coming Battle. Altogether, it was an entirely wasteful venture except for one significant indirect influence it had on the Battle of Britain, in Britain’s favour. Luftwaffe losses were 79 bombers and 68 Ju 52 transport aircraft. Among the Luftwaffe crews lost were several that were experts at blind bombing by radio beam. Training replacements greatly delayed introduction of this highly effective technique to night bombing against British industry and seaports, and cities such as London, Coventry and Liverpool, where the prime target, though denied by Germany, was the civilian population.

■ The Blitzkrieg

While this brief and hopeless campaign was being waged, the Blitzkrieg had burst upon Holland and Belgium as the first move in Germany’s long-awaited attack on France. The most important weeks of the whole prelude to the Battle of Britain were imminent. L’Armée de l’Air has always maintained that the Battle of Britain really began in May 1940, and that it has never been given due credit for the part it played in Fighter Command’s victory six months later by the damage the French inflicted on Luftwaffe aircraft and air crews in May and June.

The delay in making the assault had not been caused by the weather alone. On January 10 a Luftwaffe major flying from Münster to Bonn with the detailed operational plan for the attack was blown off course in bad weather and force-landed in Belgium. The Belgians handed the documents to the Allies and Germany had to make a new plan.

At dawn on May 10 the Luftwaffe struck. Ignoring the Maginot Line, the Germans simply went around its northern end. In addition to the brilliant use of aircraft and armour in cooperation they exploited their other new technique, the spearhead of paratroops and airborne infantry, both carried in Ju 52s. The first targets in Holland were its capital, The Hague, its main port, Rotterdam, the military airfields, and the bridges across the Rhine at Dordrecht and Moerdijk, which had to be kept intact for the advancing ground forces. In Belgium, the objectives were the two Albert Canal bridges, and Fort Eben Emael on the frontier. Paratroop engineers landed on the fort and blew up the anti-aircraft guns and artillery emplacements, with a new high explosive and equipment carried in another innovation, towed gliders. The garrison held out for 24 hours.

With 136 divisions, the Germans were outnumbered by the 149 divisions of the BEF, the French, Belgians and Dutch. But their air force was bigger than the four opposing ones combined, their tactics were dazzling and their High Command was cleverer than those of Britain and France. They also had the supreme advantage of unity, whereas communication in every respect between the British and French ground and air commands was poor. The German tanks were concentrated in armoured divisions, which gave them maximum effectiveness. The British were similarly organised, but had not sent any armour to France. The powerful French tank force was mostly fragmented in support of the infantry.

The Luftwaffe had at its disposal 860 Bf 109s, 350 Bf 110s, 380 dive bombers, 1,300 long-range bombers, 300 long-range recce aircraft, 340 short-range recce aircraft, 475 Ju 52 transports and 45 gliders.

The British Air Forces in France had seen little change since their arrival. In the Air Component, Nos. 607 and 615 Squadrons were converting from Gladiators to Hurricanes. The AASF had gained two Blenheim squadrons in place of two Battle squadrons and on the afternoon of May 10 was joined by No. 501 (Hurricane) Squadron of the Auxiliary Air Force, with which Sergeant J. H. ‘Ginger’ Lacey was serving.

The air forces of the Low Countries were rapidly swamped and their airfields captured. The Dutch Air Force, De Luftvaartafdeling, numbered 124 aeroplanes. The 1st Regiment had one reconnaissance squadron, one medium bomber squadron, and four fighter squadrons with a strength of 20 Fokker D31s and 23 Fokker G1As. The 2nd Regiment had four reconnaissance squadrons, and two fighter squadrons flying Fokker D31s and Douglas DB8s.

L’Aéronautique Belge mustered 157 aeroplanes. The 1st Regiment consisted of 59 reconnaissance types. The 2nd Regiment comprised 78 fighters: 11 Hurricanes, 13 Gladiators, 30 Fairey Foxes and 24 Fiat CR423. The 3rd Regiment had 40 reconnaissance and light bomber types.

There had been little growth in the French Air Force; indigenous manufacture was slow and deliveries were awaited from the United States. The first Bloch 151 and 152 single-seater fighters had been delivered. These had a 1,080 hp Gnome-Rhône engine, two 20mm cannon and two 7.5mm machine guns. Their top speed was 323mph (520km/h) and ceiling 32,810ft (10,000m). From February the Potez 631 had six additional 7.5mm machine guns, under the wings.

On May 10, 1940, which is when the French insist that the Battle of Britain began, l’Armée de l’Air fighter groupements and groupes had available to them 828 combat aircraft, of which 584 were serviceable. Of these serviceable aircraft, 293 were Morane Saulnier MS 406s, and 121 were Bloch 151 and 152; the others were Curtiss 75s, Dewoitine 520s and Potez 630s and 631s.

Operationally, l’Armée de l’Air basic organisation was territorial, with four Zones d’Opérations Aérienne: Nord (ZOAN), Est (ZOAE), Sud (ZOAS) and Alpe (ZOAA).

While the Dutch and Belgian Air Forces were being knocked out and the vagaries of the rudimentary control and reporting system were starving the British Air Forces in France of information, both the AASF and Air Component were hectically embroiled in the air battle. Nos. 85, 87, 607 and 615 Squadrons had seen little action hitherto. No. 1 Squadron had shot down 26 enemy aircraft, and No. 73 Squadron 30 during their first eight months in France. From May 10 onwards all the fighter squadrons were fully stretched from dawn to sunset.

On the first day of the Blitz, Kain bagged a Do 17. On the following day he shot down another and a Bf 109. On the 12th, an HS 126. Orton, who by now also had a DFC, was shot down on the 10th but got his own back the next day by destroying a Ju 88 and a Do 17. Clisby, the fiery and aggressive Australian, made two kills on the 10th, both Do 17s, before being hit by French anti-aircraft fire. On the 11th he brought three Bf 109s down, followed on his last sortie that day with an He 111. This landed in a field and Clisby lobbed in beside it to make sure none of the crew got away. One of them did run for it, but Clisby sprinted after him and brought him down with a rugby football tackle.