1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

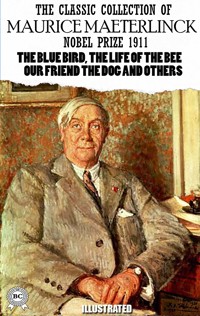

Maurice Maeterlinck's "The Blue Bird" is a poignant allegorical play first published in 1908 that explores the themes of happiness, fulfillment, and the quest for knowledge. Set against a dreamlike backdrop, the story follows two children, Tyltyl and Mytyl, on their quest for the elusive Blue Bird, a symbol of true happiness. Maeterlinck employs a lyrical and symbolic literary style that weaves together elements of mysticism and existential inquiry, creating a rich tapestry of metaphor that invites readers to ponder the deeper meanings of life. The play aligns with the Symbolist movement, characterized by its emphasis on emotional experience and inner truths, as well as an exploration of the metaphysical realms that lie beyond the material world. Maurice Maeterlinck, a Belgian playwright and poet, was deeply influenced by the Symbolist philosophy, which sought to transcend conventional reality through metaphoric language and imaginative exploration. Born into a privileged family in 1862, Maeterlinck's literary career was shaped by his interests in philosophy, nature, and the human condition, as evidenced in his earlier works. His pursuit of understanding happiness and the human experience culminated in "The Blue Bird," a quest that resonates with universal human themes. This enchanting play is recommended for readers seeking a profound exploration of happiness and the human spirit. "The Blue Bird" serves as both a work of art and a philosophical treatise, making it essential reading for those interested in the convergence of literature and existential thought. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Blue Bird

Table of Contents

Introduction

A small blue bird flits just beyond reach as two children set out to grasp the meaning of happiness. Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird transforms this simple image into a luminous journey where the everyday gains a secret radiance and the invisible presses close to the visible. Framed as a quest, the play invites readers and audiences to look anew at their surroundings, to feel how objects, memories, and hopes tremble with life. Without heavy didacticism, it offers a path through wonder, guiding us by gentle steps toward questions that linger long after the curtain falls: What do we seek, and how do we learn to see it?

The Blue Bird is considered a classic because it crystallizes the aspirations of Symbolist drama while remaining delightfully accessible. Maeterlinck fuses fairy-tale adventure with philosophical resonance, creating a work that altered expectations of what theatre for all ages could do. In place of gritty naturalism, he proposes an imaginative stage where ideas wear faces and human longings speak. The result influenced the visual and poetic ambitions of modern directors and playwrights, proving that spectacle can be contemplative and that children’s stories can carry adult wisdom. Its continuing revival across decades attests to a text both theatrically fertile and emotionally durable.

Maurice Maeterlinck, a Belgian playwright who wrote in French, composed The Blue Bird in the early twentieth century. The play premiered at the Moscow Art Theatre in 1908, in a landmark production directed by Konstantin Stanislavski, and it soon traveled widely in print and performance. Maeterlinck received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1911, recognition in which this play played an important part. Set in motion by a quest assigned to two siblings, the drama proceeds through a series of fantastical encounters that test their senses and sympathies. It is a moral and poetic exploration rather than a puzzle, framed for the stage.

At its simplest, the play follows two children asked to find a rare bird that symbolizes happiness. Their guide is a benevolent figure who opens doors to realms usually closed to human eyes, and their companions include beings drawn from the household and the elements. Each stage of the journey presents an invitation to look differently at life: into the past and its tender echoes, into the night and its guarded mysteries, toward the future with its fragile promises. Without divulging outcomes, one can say the quest refines longing into insight, offering experience rather than trophies as its true reward.

Part of the play’s power lies in how it treats the theatre itself as a lantern of revelation. Maeterlinck deploys personification, shifting tableaux, and luminous imagery to create a stage language that feels both intimate and enchanted. The play does not abandon narrative, yet it privileges atmosphere, rhythm, and suggestion over literal explanation. This gives directors and designers room for invention, from lighting that carves shadows into meaning to costumes that render concepts tangible. What might have been mere ornament becomes a way of thinking, an argument in images that encourages audiences to participate, completing symbols through their own imagination.

As a Symbolist, Maeterlinck was fascinated by the forces that move beneath ordinary speech, and The Blue Bird makes those forces speak. The drama addresses the elusive nature of happiness, the beauty of everyday things, the fidelity of memory, and the responsibilities of hope. It meditates on time as a living presence, on gratitude as a form of knowledge, and on the relationship between desire and perception. The play’s gentle humor and affection for its young protagonists ground these concerns, ensuring that the metaphysical never drifts far from the homely and humane. The result is a balance of wonder and wisdom.

The book’s influence reaches beyond literary history into the practical craft of performance. It encouraged twentieth-century theatre-makers to experiment with nonliteral spaces, to animate props and settings with meaning, and to treat children’s drama as aesthetically serious. Its echoes can be heard in later works that blend fable with philosophy, presenting quests whose destinations are inward. Adaptations across media have kept its images in circulation, reinforcing its reputation as a touchstone for imaginative storytelling. While other movements rose and fell, The Blue Bird remained a resource for artists seeking to reconcile spectacle with inwardness and childhood with sophistication.

Maeterlinck’s language, while simple enough for young audiences, has a pearly clarity that invites reflective listening. Dialogue flows with a musical cadence, moving from playful to solemn without strain. The characters, many of them personifications, speak in tones that reveal both their archetypal roles and their human warmth. This stylistic poise makes the play unusually flexible: it can be read privately as a theatrical poem or staged as an event of communal wonder. The simplicity is purposeful, allowing resonances to rise like overtones. Readers discover that even the quietest exchanges vibrate with possibility, shaping a mood that lingers delicately.

The Blue Bird also reflects Maeterlinck’s longstanding interest in the unseen dimensions of existence. In essays and plays alike, he sought forms that could gesture toward mystery without forcing it into doctrine. Here, he counterposes the tangible and the intangible, suggesting that what we handle daily may harbor meanings we can only approach through symbol and story. The play does not preach a single creed; it models a kind of attentive receptivity. In this sense, it belongs to a broader modern effort to recover wonder within a technological age, not by rejecting reason, but by allowing imagination to complete reason’s outline.

Contemporary readers will find the play strikingly current. Its questions about how to recognize fulfillment, how to honor memory without being imprisoned by it, and how to care for the world we touch speak to present anxieties. The personification of natural forces and domestic objects suggests a respectful ecology of attention, urging us to notice the lives entwined with ours. At the same time, the children’s journey honors courage, kindness, and patience as arts of living. The play’s accessibility makes it suitable for family reading, yet its layers reward rereading, offering renewed nuances as life itself grows more complex.

Approaching The Blue Bird, it helps to lean into its theatricality. Imagine how light might reveal or conceal, how a costume could make an abstraction palpable, how music might accompany recognition. Read it as a ceremony of seeing, a sequence of rooms where perception changes temperature. Do not rush to decode every emblem; the play prefers slow understanding and the hush that follows discovery. Its structure invites participation, as if audience and reader alike bring the final color to its wings. This attitude of receptive attention makes the experience more than a story: it becomes a practice of awareness.

In sum, The Blue Bird endures because it weds the enchantment of a fairy tale to the maturity of a philosophical meditation. Written by Maurice Maeterlinck in the early twentieth century and launched onstage in 1908, it stands at a pivotal moment in theatrical history, proving that spectacle can serve thought and that children’s quests can deepen adult feeling. Its themes—happiness, gratitude, time, and the wonder of the near at hand—continue to resonate. For contemporary audiences, the play offers a tender, luminous guide to seeing anew, and it remains a classic because it keeps teaching us how to look.

Synopsis

Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Blue Bird is a symbolist stage tale about a brother and sister, Tyltyl and Mytyl, who live in modest circumstances. On a winter night, the enigmatic Fairy Berylune arrives and asks them to seek the Blue Bird, a creature said to bring lasting happiness to a suffering child. She gives Tyltyl a hat set with a diamond that, when turned, reveals the inner life of things. Light herself appears to guide them. Thus begins a journey across visible and invisible realms, where abstractions and household objects awaken, and where the children must learn to recognize true joy.

Before setting out, the ordinary room transforms. The family’s Dog becomes Tylo, exuberant and loyal; the Cat, Tylette, sleek and calculating. Fire, Water, Bread, Sugar, and Milk step forward as talkative companions with distinct temperaments. Under Light’s leadership, the troupe accepts a cautious truce, for some are friendlier to humans than others. The mission is straightforward yet elusive: find the Blue Bird wherever it may hide and return it to the fairy’s charge. The diamond will disclose what lies behind appearances, but using it demands judgment. With farewells said, they leave the safety of home and enter the first of many domains.

Their initial destination is the Land of Memory, a place where the past remains tenderly alive. There the children meet their deceased grandparents and siblings in a scene that feels both ordinary and enchanted. Time pauses, daily rituals resume, and affection bridges the boundary between living and dead. The visit reassures the travelers that love endures beyond absence, but it also reminds them that they cannot remain. The Blue Bird seems near among familiar comforts, yet it does not answer their call. When the appointed hour passes, Memory releases them, and Light guides the party onward toward more formidable thresholds.

They next brave the Palace of Night, a stronghold where mysteries, terrors, and forbidden rooms lie locked. Night seeks to delay or mislead them, wary that Light may unveil what should sleep. As the children move through vaults labeled with calamities and fears, they glimpse dangers contained by vigilance and hope. The Blue Bird might be hidden here, but reaching it would require surrendering to darkness. Instead, the travelers press on, testing courage without courting disaster. The sequence emphasizes how illumination alters threat, and how curiosity must be tempered by prudence. Emerging from Night’s dominion, they resume the search with care.

In the awakened Forest, the trees, animals, and elements hold council against humanity. Resentments simmer over axes, fires, and centuries of harm. Tylette whispers treacheries, yet Tylo throws himself between peril and the children. Fire almost turns from servant to destroyer, Water resists control, and branches hem the path. The travelers learn that nature’s voices include grievance as well as beauty, and that companionship carries both loyalty and deceit. Their escape depends on Light’s presence and the steadiness of purpose the quest demands. Though tempted to abandon the effort, they persevere, still without the bird that would end their journey.

The path leads to halls and gardens where pleasures and satisfactions parade their charms. In the Palace of Luxury, dazzling abundance threatens to lull the seekers into comfort and forgetfulness. Nearby, the Happinesses reveal themselves, from grandiose public triumphs to quiet domestic contentment. The children observe that some joys glitter briefly while others sustain everyday life, yet choices must be made without losing sight of the mission. The Blue Bird flits among these illusions and truths, never quite within reach. Light counsels balance, and the companions move on, a little wiser about the difference between delight and durable well-being.

Drawn to a silent cemetery, the children are invited to turn the diamond and regard what lies behind stone and soil. In the gentle radiance, the scene becomes unexpectedly familiar, as if separation were only a change of state. Those they love seem near, not tragic. The moment consoles but does not conclude the quest. The Blue Bird does not dwell in the stillness of graves, nor can the travelers remain in contemplation. With reverence, they lower the veil once more and depart. The episode affirms continuity and tenderness without halting the forward motion of the search for happiness.

Finally they arrive at the Kingdom of the Future, where unborn children prepare for life with dreams and tasks still to come. Here wait beings destined to bring inventions, discoveries, and kindnesses to the world, each guarded by Time. The realm is active yet patient, brimming with possibility that must ripen before appearing on earth. The visitors glimpse the scale of human hope and the responsibilities that accompany it. Although the Blue Bird seems almost attainable amid such promise, the hour of return approaches. Time insists, the company withdraws, and Light turns their steps back toward the place from which they started.

Back at home, the quest’s meaning becomes clear through changed perception rather than dramatic conquest. The children take stock of what they have seen and what remains. Their encounters with Memory, Night, Nature, Pleasure, and the Future have taught them to look closely at the near and the ordinary. The Blue Bird, symbol of happiness, proves less an exotic rarity than a measure of understanding, gratitude, and sharing. Without disclosing a single final surprise, the story closes by affirming that genuine contentment may be found close at hand. The journey endures as a gentle invitation to recognize joy where we live.

Historical Context

The Blue Bird unfolds on Christmas Eve in a modest, unnamed European town whose contours evoke early twentieth-century domestic life: a woodcutter’s cottage, a hearth, a pantry where bread and sugar are rationed, and a window onto a dark forest. From this familiar scene the children, Tyltyl and Mytyl, traverse allegorical realms—the Palace of Night, the Land of Memory, and the Kingdom of the Future—spaces that mirror real social institutions by transforming them into moral landscapes. The temporal framing is deliberately at once seasonal and timeless, yet its material details, vocabulary of scarcity, and bourgeois-neighborly proximity imply a Western European setting c. 1900.

The geography of the narrative stretches from a small home toward domains that encompass the past and unborn years, enabling the play to juxtapose close-knit family poverty with vast social questions. Rural work rhythms, a dependence on wood and fire, and the ritualized generosity associated with winter holidays frame the action. The itinerary—visiting the dead, opening doors of guarded storehouses, meeting children awaiting birth—maps the anxieties and hopes of industrial Europe before 1914. It is a world where everyday goods, animals, and natural elements are personified, giving voice to the social pressures embedded in food, labor, light, illness, and memory.

The Belle Époque (approx. 1871–1914) saw rapid urbanization, consumer display, and sharp inequalities in Belgium and France. Brussels expanded under King Leopold II (reigned 1865–1909), while Paris rebuilt boulevards and staged world fairs. Railways, department stores, and electrified streets expanded opportunities and temptations, but also accentuated class divides. Wage labor, domestic service, and artisanal trades coexisted uneasily with new fortunes. The Blue Bird situates a poor craftsman’s family adjacent to comfort they cannot access, dramatizing the Belle Époque paradox: dazzling abundance alongside hardship. Tyltyl’s quest for happiness reads as a counterpoint to the era’s equation of prosperity with joy, proposing ethical rather than material criteria.

Across Europe, late nineteenth-century reforms redefined childhood. France’s Roussel Law (1874) restricted child labor in factories; the 1892 French labor law limited hours for minors; weekly rest was broadened in 1906. Belgium’s 1889 law curbed child labor and night work for women and adolescents, reflecting growing concern about schooling and health. Charitable societies and pediatric medicine expanded. These measures recast children as protected citizens-in-formation rather than small workers. The Blue Bird, with children as moral agents who instruct adults in the meaning of happiness, mirrors this historical turn: the Kingdom of the Future stages unborn children as society’s promise, not its expendable labor reserve.

Industrial cities concentrated poverty in crowded districts—Brussels’s Marolles and Paris’s peripheral faubourgs—where rents rose and sanitation lagged. Legislators and philanthropists responded with workers’ housing initiatives: in Belgium a law of 1889 encouraged habitations ouvrières, and private sociétés d’habitations à bon marché multiplied in the 1890s; in France, similar societies formed after 1894. Yet scarcity and insecurity persisted. The Blue Bird’s pantry scene, in which Bread and Sugar acquire voices and intentions, reflects the precariousness of provisioning in such households. Happiness must be sought amid shortages, not beyond them, and the play’s domestic starting point anchors its moral journey in the realities of working-class subsistence.

Between 1895 and 1909, scientific and technological breakthroughs changed daily life. Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays (1895); Henri Becquerel identified radioactivity (1896); Marie and Pierre Curie earned the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics. Urban electrification accelerated after the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Aviation leapt from experiment to spectacle: the Wright brothers flew in 1903; Louis Blériot crossed the English Channel in 1909. In The Blue Bird, Light becomes a guiding personhood, and the Kingdom of the Future foregrounds children anticipating inventions and social improvements. The play thus channels contemporaneous wonder while insisting that technique alone cannot generate the enduring happiness the era so confidently pursued.

The late nineteenth century witnessed a surge of interest in spiritualism, ancestor veneration, and psychical research, entwined with Catholic and secular mourning cultures. The Society for Psychical Research was founded in London in 1882; Allan Kardec’s Spiritist writings circulated widely in France and Belgium after 1857. Commemorations of All Souls’ Day and family grave visits structured memory in Catholic regions. The Blue Bird’s Land of Memory, where grandparents arise warmly when the children arrive, redeems these practices from superstition, proposing memory as an ethical duty linking generations. It reflects a society managing grief and change by treating the dead as active members of the moral household.

World’s fairs were emblematic of the era’s faith in display. The 1889 and 1900 Paris Expositions showcased electricity, moving sidewalks, and colonial “villages.” Brussels staged the 1897 International Exposition with a vast Congo section in Tervuren, where Congolese people were exhibited in reconstructed settings; several died during the event. Spectacle translated possession into vision. The Blue Bird’s insistence that the coveted bird eludes capture, always paling once seized, reads as a rejoinder to the exhibitionary gaze: seeing is not owning, and possession can destroy value. The quest critiques a culture that believed happiness could be curated, staged, and consumed like a pavilion.

From 1885 to 1908 the Congo Free State existed as the personal domain of Belgium’s King Leopold II, internationally recognized at the Berlin Conference (1884–1885). Administration relied on concession companies and the Force Publique to extract rubber and ivory, enforcing quotas through hostage taking, floggings, and the infamous practice of collecting severed hands as proof of munitions use. The global bicycle and automobile booms of the 1890s–1900s drove demand for rubber, escalating coercion. Mortality from violence, disease, and flight produced a demographic catastrophe; estimates of population loss range into the millions, though precise figures remain debated because censuses were absent.

Reform efforts crystallized between 1903 and 1908. The British consul Roger Casement’s 1904 report documented atrocities; journalist E. D. Morel formed the Congo Reform Association in 1904, mobilizing an international network of churches, newspapers, and parliamentarians. Missionaries contributed testimony and photographs that circulated in Europe and the United States. Under mounting pressure, Leopold II instituted commissions of inquiry, while critics demanded an end to concessionary abuses. In 1908, after protracted debate in Brussels, the Belgian Parliament annexed the territory as the Belgian Congo, ending personal rule. Although exploitation persisted, annexation marked a political acknowledgment of scandal at the heart of a putatively civilized Europe.

Maeterlinck, a Belgian writing and premiering The Blue Bird in 1908, inhabited this climate of moral reckoning. The play does not mention Congo, but its core drama—refusing to equate possession with happiness, dignifying humble life, and extending compassion to animals and elements—aligns with the humanist critique that animated Congo reform. Personified Sugar, Fire, and Water embody appetites and powers that require restraint; Light presides as a moral intelligence. The story’s insistence that true happiness exists at home, among living bonds rather than acquired trophies, counters the imperial logic of distant conquest and exhibition, offering an ethical imaginary that resonates with anticolonial conscience.

The play’s first production occurred at the Moscow Art Theatre in 1908, under Konstantin Stanislavski and Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko. Russian society was still reeling from the 1905 Revolution—Bloody Sunday in January 1905, strikes, peasant unrest—and the October Manifesto’s promise of civil liberties and a State Duma (first convened in 1906) had not quelled discontent. Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin’s reforms and repressions defined the years 1906–1911. In this tense environment, fantastical allegory provided a rare public language for hope. The Blue Bird’s vision of attainable happiness without violence or expropriation spoke to audiences wary of both czarist severity and nihilistic despair.