Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

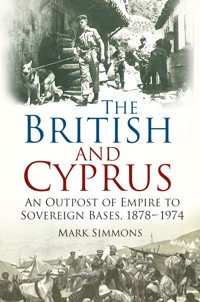

The relationship between Britain and Cyprus over the course of the past 100 years has been a constantly evolving one. Since the First World War, Cyprus has played a key role in British defence strategy, and, after the withdrawal from Egypt, the island became the British Middle East headquarters. Today, Britain retains two sovereign bases in Cyprus and the island has become a popular holiday destination for many British tourists. Using previously unpublished letters and personal interviews, The British and Cyprus is told through the words of the people who served the British Crown on Cyprus – civil and military – and includes fascinating accounts of the dramatic fight against EOKA in the 1950s, who pressed for an end to British rule on the island.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 385

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of my Father

Albert Frederick Thomas Simmons (Tommy), Royal Navy

and my friend

Albert James Ley, Royal Marines,

both of whom served on Cyprus.

With the archways full of camels

And my ears of crying zithers

How can I resolve the cipher

Of your occidental heart?

How can I against the City’s

Syrian tongue and Grecian doors

Seek a bed to reassemble

the jigsaw of your western love?

‘Port of Famagusta’, Laurie Lee, Cyprus 1939

Cover illustrations. Front, top: Author’s collection; bottom: Illustrated London News. Back: Author’s collection.

First published 2015

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mark Simmons, 2015

The right of Mark Simmons to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7509-6581-1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Glossary

List of Abbreviations

Introduction

1 The Early Years

2 The First World War

3 Crown Colony: The Interwar Years

4 The Second World War

5 The Gathering Storm 1947–1954

6 A Corporal’s War 1955

7 1956 Clearing the Forests

8 1957 Stalemate

9 1958 Bloody Civil War

10 1959 Agreement in Room 325

11 Anywhere’s Better than Here 1960–1973

12 Unfinished Business 1974

13 Bellapais 2000 and Waynes Keep 2004

Afterword

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book like this is an oral history of the British involvement with the island of Cyprus, a special place to many peoples and races down the ages, and to the British to this day – be they servicemen, ex-pats, or tourists – and could not have been written without a great deal of help.

I owe a huge debt to many people who, with great kindness, have made available valuable original material in the form of diaries and letters.

The Royal Navy, because Cyprus has no real natural harbour and never became a fleet base, had little direct contact with the island. However I am grateful to the late Tom Simmons, my father, for his yarns about 1947. And also Corporal T.A. Hannant RM for the exploits of HMS Hermes in 1974.

My own Corps, the Royal Marines, came up with a wealth of information. Brian F. Clark (Bomber), the secretary of the 45 Commando ‘Baker Troop’ association, spent most of a winter’s afternoon relating his experiences in Cyprus and Suez during the 1950s. He even gave me a copy of the Troop Journal, which was invaluable and largely instrumental in persuading me to write the book.

Thanks also to the late OC Baker Troop Major F.A.T. Halliday, and troop members Colin Ireland, Sergeant Derek Wilson, George Ferguson and John Cooper. The Troop Journal is in the Royal Marines Museum in Eastney. It is now available as a Royal Marines Historical Society publication, Cyprus Crisis 1955–1956.

Colonel Tim Wilson also gave much information on the deployment to Cyprus of 40 Commando in 1955 as did Fred Hayhurst, and to all my ‘oppos’ in the 40 Commando association who shared their yarns with me.

Spike Hughes wrote from Spain about his time in Support Troop 45 Commando and Operation Lucky Alphonse also featured in A Fighting Retreat, by Robin Neillands, another former Royal Marine. The stories of Marine David Henderson, 45 Commando, and Captain A.W.C. Wallace RM, came from Britain’s Small Wars website.

The story of Arnold Hadwin I came across in The Light Blue Lanyard, the story of 40 Commando RM by Major J.C. Beadle, which was first published in the Lincolnshire Evening Despatch.

Former soldiers were just as helpful. Twin brothers Richard and Mike Chamberlain did their National Service with the Royal Corps of Signals and left a vivid picture of Cyprus just prior to the EOKA troubles, through the paper Cyprus Today.

Charles Butt, who served with the Intelligence Corps Field Security Section, sent me a wealth of information and helped with some searching questions about the EOKA period. It was Charles who directed me to the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum.

The British Empire and Commonwealth Museum also supplied me with oral history tapes for R.W. Virant, Royal Corps of Transport, and Lieutenant Colonel Wilde, Royal Engineers.

Gary Spencer served with Royal Army Medical Corps during the 1974 troubles helping Cypriot refugees in the Athna Forest Camp. John Johnson, 4th Royal Tank Regiment, served with the UN.

Colonel Colin Robinson did several tours of duty in Cyprus, in particular in the early months of 1964 with the 16th Parachute Brigade.

Hugh Grant, another Para who served in Cyprus during the last few months of the EOKA troubles, wrote A Game of Soldiers, another gem. As was Airborne to Suez, the memoirs of Sandy Cavenagh, Medical Officer of 3 Para, the early chapters of which cover his time on Cyprus.

Gordon Burt, another member of the Parachute Regiment, came from the archives of the Imperial War Museum as did the fascinating story of Major W.C. (Harry) Harrison, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who was seconded to the Cyprus police as the Government explosives expert.

Auberon Waugh’s memoirs Will This Do? told of his National Service with the Royal Horse Guards, and his description of the Guenyeli massacre was graphic.

The story of the Ashiotis Incident from the late Alan (Gunner) Riley came from his oppo Dave Cranston, both ex-Royal Ulster Rifles, through the Britains-small-Wars website.

The Royal Air Force has had a long association with Cyprus. Squadron Leader Norman E. Rose and Squadron Leader Colin A. Pomeroy gave a grandstand view of the 1974 invasion. Geoff Bridgman for the 1980s. Raymond A. Ferguson for his yarns as a regular airman toward the end of the EOKA troubles. Thanks to Group Captain L.E. (Robbie) Robins, AEDL, for his thoughts about Cyprus during various visits and supplying illustrations, free use of his extensive library and his general hospitality.

Vyv Walters for his view of Cyprus in the last twelve months before the 1974 invasion. And Robert Gregory for his nine-day rides around Cyprus on a motorbike in 1942.

Jack Taylor, former Royal Marine and policeman, served with the Cyprus police through much of the EOKA troubles, his memoirs A Copper in Kypriou being another rare find.

Civilians were, perhaps, understandably not so forthcoming. However, the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum oral tapes library supplied me with the memories of Mr Lennard, a Colonial District Officer, who arrived on Cyprus with his family two weeks after the first EOKA bomb attack. His wife Mary-Pat’s views on civilian life at the time were helpful. Thanks to Mrs Hazel Fowdrey, wife of Doctor Alan Fowdrey, for a wartime picture, and Faith Lloyd, who served with the Red Cross in Palestine and Cyprus 1949–51, and Sheila Mullins for her thoughts on teaching Greek Cypriot children at Bermondsey Primary School and her visits to Cyprus, and to Jan Bradley for her memories of the 1974 invasion.

The Imperial War Museum supplied the diary of Mrs Sommerville, a service wife who was a contemporary of the murdered Catherine Cutliffe. Thanks to the late Edward Woodward OBE and John Parker.

Museum personnel were most helpful: Doctor Gareth Griffiths, Director of the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum, and Mary Ingoldby, the oral history co-ordinator. Sadly the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum closed in 2008 and was wound up in some controversy in 2012. Thanks also to Stephen Walton, archivist at the Imperial War Museum.

Thanks to M.G. Little, archivist Royal Marines Museum, and Y.H. Kennedy at the Historical Records Office Royal Marines.

James Crowan, reader services at the Public Records Office who steered me in the direction of HMS Comet and Charity, and Kate Tildesley from the Ministry of Defence Naval Historical branch who helped with the above.

Many publications were helpful: Captain A.G. Newing at The Globe and Laurel, journal of the Royal Marines; the editor of Pegasus, journal of the Parachute Regiment; the editor of RAF News and the RAF Association; NESA News publication of the National Ex-Services Association; Gill Fraser at Cyprus Today; the editor of Soldier magazine and the Legion magazine, and Britain’s Small Wars website; and The Thin Red Line, the regimental magazine of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

Some more rare books were helpful: Suha Faiz’s memories of an Unknown Cyprus Turk recommended to me by the Green Book Shop, Kyrenia, Northern Cyprus.

My local second-hand bookshop, Bookends of Fowey, obtained for me The Memoirs of General Grivas, edited by Charles Foley, and Foley’s own Island in Revolt.

Lawrence Durrell’s Bitter Lemons of Cyprus was another insight into the EOKA period. Colin Thubron’s Journey into Cyprus gives a memorable picture of the island prior to the invasion and division of 1974, and I can sympathise with his blistered feet; mine too have suffered on Cyprus. Also Penelope Tremayne’s, Below the Tide, gave a great insight into living in Greek Cypriot villages during the troubles.

To Shaun Barrington, my commissioning editor at The History Press, for continued support, and to John Sherress, fellow author, always a good proving ground.

And to Margaret, my dear wife who too has suffered from blisters on Cyprus. And proofread most things I have written, and typed and edited so many things.

To all these I am grateful and to those that lack of space prevented an account from being included, their view was important in the overall story. Many thanks to all.

GLOSSARY

Attila

Turkish Army operation code name for 1974 invasion of Cyprus

Black Mak

Soldiers’ slang for Archbishop Makarios

Camp K

British detention camp near Nicosia used for EOKA suspects

CFBS

Cyprus Forces Broadcasting Service

Clear Lower Deck

Situation Report to all ranks Royal Navy and Royal Marines

Dighenis

George Grivas’s code name. Mythical figure in Cyprus history and mythology

Enosis

Political union of mother Greece and Cyprus

EOKA

National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters

EOKA-B

Second coming of above (1974)

GNG

Greek National Guard. Cypriot Army with Greek mainland officers

GPMG

General Purpose Machine Gun

Green Line

United Nations buffer zone between North and South Cyprus, policed by UN troops

GUZ

Naval slang for Plymouth, Devon. Believed to come from the First World War identification letters for the port

KOYLI

King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

LCVP

Landing Craft Vehicle and Personnel

Mason–Dixon Line

Dividing Nicosia between Turks and Greeks. Taken from the line that divided the slave states from the free in the USA

Murder Mile

Lendra Street, Nicosia

MMG

Medium Machine Gun (Vickers)

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

Oxi Day

28 October Greek celebrations over the defeat of the Italians in the Second World War

Q Patrols

Police vehicle patrols in towns

RUR

Royal Ulster Rifles

Sangar

Small sandbagged defensive gun position

SBA

British Sovereign Base Area

SLR

Self-Loading Rifle

TMT

Turkish terrorist group

TRNC

Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

Uhi

Remote area of landscape

UNFICYP

United Nations Force in Cyprus

Volkan

Turkish counter-terrorist organisation that pre-dates TMT

Xhi

Greek right-wing resistance group during the Second World War

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations have been used in the notes, which appear at the end of each chapter.

ADM-(PRO)

Admiralty – National Archives (Public Records Office)

CIA

Central Intelligence Agency USA

(DEFE)-(PRO)

Defence Office

FCO-(PRO)

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

KV-(PRO)

Security Service Files

WO-(PRO)

War Office

BECM/Oral Tape

British Empire and Commonwealth Museum/Oral Tape

ITA

Interview with the author

IWM

Imperial War Museum

LTA

Letter to the author

INTRODUCTION

Kolossi Castle 1974 and 1992

On the night of 19 July 1974 an RAF Nimrod XV241, from No. 203 Squadron, in the maritime reconnaissance role, took off from Luqa Airbase Malta. It climbed into a starlit night sky turning east, its objective the island of Cyprus just over 1,000 miles away.

XV241 co-pilot Colin Pomeroy was initially disappointed at missing the Annual Summer Ball in the Officers’ Mess that night but was about to see history in the making. Colin recalls the approach to Cyprus:

Some 150 miles out we could clearly see from the flight deck, fires burning out of control on the Troodos Mountains and soon we were down at low level off Kyrenia above the grey invasion fleet. Although we were scanned by search and fire control radars, not one anti-aircraft gun pointed upwards at us, which was most comforting, but we made a point of neither flying directly over or towards any of the Turkish Warships.1

On that same July day the Commando Carrier HMS Hermes with 41 Commando Royal Marines embarked, arriving off the southern shore of Cyprus. Hermes had arrived off Malta, home then for 41 Commando, three days earlier after a deployment to the USA and Canada. However, the declining situation on Cyprus had required the diversion to the island for an ‘indefinite period’. On 21 July the main body of the Commando were flown off Hermes into the Eastern Sovereign Base Area of Dhekelia.2

Two thousand, three hundred airline miles to the north-west the advance party of 40 Commando Royal Marines, the United Kingdom Land Forces Spearhead Unit for July, had left Seaton Barracks, Plymouth, for RAF Lyneham and air transport to Cyprus to reinforce the garrison. Nobody knew quite what to expect. Yours truly, a young Marine Commando then fresh from training, would be in the next wave.

All this activity was the result of the Turkish invasion of 20 July, an event that many on Cyprus and in Greece to this day blame on the British. To them it was the fruition of nearly 100 years of misguided rule, and involvement with the island, by Britain.

In 1992 I returned to Cyprus for the first time since the invasion of 1974. Yet nearly twenty years on it all looked so different. From Kolossi Castle’s sandstone battlements I tried and largely failed to locate the old position I and my fellow Marines had occupied. The Vehicle Check Point (VCP) had been on the north side of the Episkopi–Akrotiri SBA.

It had been within sight of the castle which was just outside the base area. The original Crusader castle was built in 1210, more than likely by the order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem, otherwise known as the Hospitallers. The order lives on today with its headquarters at Valletta, Malta. However, the castle passed between the two great orders, the Hospitallers and the Templars, over the years until the latter were indicted for heresy. Some say the present castle dates from 1454 built on the ruins of the original.

The keep is over 70ft high, and in the east side is a panel bearing the coat of arms of the Lusignans. Here abouts the knights cultivated vines that produced Commandaria, one of the oldest wines that are still drunk. Thick and sweet, more like a fortified wine, ‘it was famous throughout European Christendom, and fuddled successive Plantagenet Kings’.3 On the south side of the sugar factory there is an inscription saying the building was repaired in 1591 when Murad was the Pasha of Cyprus. The Englishman Fynes Moryson, who passed this way in 1596, commented on the cultivation of sugar-cane and the use of the mills. By 1900 the Scotsman Cecil Duncan Hay, with his family, lived on the Kolossi estate in a house attached to the keep. He planted the cypress trees that are now taller than the keep, while the family used one of the huge castle rooms as a badminton court.4

Somewhere nearby sandbags had been filled to build the sangar. Our task was to regulate the flow of traffic in and out of the SBA, which included members of the Greek National Guard and the Greek Cypriot Defence Force, Turkish and Greek Cypriot refugees. For in the face of the Turkish invasion, people flooded into the British Bases, mainly Turkish Cypriots to Episkopi-Akrotiri, Greek Cypriots to Dhekelia and foreign nationals and tourists to both.

The invasion was the result of a mainland Greek plot, by the Military Junta then in power in Athens, to bring about Enosis, the union of Cyprus with Greece, by deposing the Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios. Makarios had once been a champion of Enosis but had come to realise it could never work given the volatile mix on Cyprus and the stance of Turkey. Enosis was not a new idea even in the 1950s. Indeed at the start of British rule in 1878 the Bishop of Kition, welcoming Sir Garnet Wolseley landing at Larnaca, raised the subject, hoping Cyprus could in time be ‘united with Mother Greece, with which it is naturally connected’.5 The only concrete result of the 1974 plot was the invasion by Turkey and the division of the island along the Green Line; thus the Greeks had really scored an own-goal.

I walked along the Akrotiri road half hoping to find the sangar, or even a rotting sandbag or discarded entrenching tool. Off-duty time had been passed reading or listening to the forces radio. There had been tense night patrols amid the plantations to ‘dominate the ground’ and stop arms smuggling through the base area. Once we put out a ‘contact’ report over the radio when a donkey jumped us. The Greek National Guard fired on us across the border. They thought we were Turkish paratroops was one yarn we were told, while another was that we had taken an offensive stance with our observation posts overlooking the SBA boundary. A Marine from A Company was wounded in another encounter, but in this case fire was returned, wounding one of the Greek National Guard who later died.

A little disappointed with Kolossi Castle and my memory, I took the road north toward the distant dark Troodos Mountains. The road climbs gently through a white rocky landscape. The thin white-grey soil is ideal vine country and vineyards are dotted everywhere across the terraced ground. The villages around here are known as the ‘Commandaria Villages’, after the wine favoured by the Crusaders.

At Pano Kivides I stopped, pano means above or higher. The village, once Turkish, is abandoned. You have to drive down a bumpy lane even to get to it. The only noise came from a lizard that scurried away at my approach. The buildings were eerie and the village had a Pompeii-like quality. But now the houses were only frequented by the odd roving goatherd. For its people village ties were stronger than national or religious belief. The fact that more Greeks were displaced and moved south to the Turks who went north is a statistic bad enough in its own way but it cannot tell the tragic story of every village, family and person.

In 1974 there were atrocities on both sides. Within the SBA was safety, but outside was different. East of Limassol at the mixed village of Tokhni an EOKA-B gang murdered all the Turkish men over the age of 16. That village even today has a haunted atmosphere.

EOKA had been formed by Archbishop Makarios, General George Grivas and others; in 1953 its sole aim was union with Greece by force. EOKA means ‘National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters’ (in Greek transliteration Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston). In 1971, Grivas returned to Cyprus in secret, disguised as a priest, to organise the EOKA- B, meaning EOKA number two or the second, with the blessing and backing of the colonels in Athens. Grivas died in January 1974 before the July coup against his old ally Makarios. Nicos Sampson led the EOKA-B during the coup and Turkish invasion and usurped presidential power, however only holding the post for eight days. He was a former murder group leader in the 1950s terrorist campaign and was known as the ‘chief executioner on Ledra Street’. He became ‘vilified by many, admired by few’. He would have his photo taken with one foot atop the corpse of a Turkish Cypriot he’d killed. Under his leadership EOKA-B killed more Greek opponents than Turks, and buried many of the former in unmarked graves. Afterward he tried to plead he had been forced into the office by the Greek Junta; however he quickly resigned. With the return of Makarios he was tried for treason, found guilty and sentenced to twenty years in prison.6

Some 300 Turks were murdered at Tokhni and some villages near Famagusta, and it is believed some 2,000 Greek Cypriots disappeared in Turkish hands during the same period, some being deported to Turkey for interrogation.

The nature of the Greek Cypriot has changed. The events of 1974 are partly responsible. The loss of Kyrenia and Famagusta, the best resorts, resulted in panic building in the south and an overemphasis on tourism. Over half the population are now involved in the trade; they say Cypriots dream of ‘hotels and taxis’. The youngsters dream of leaving the island; at 8 years of age they start to learn English.

From Pano Kivides I headed for Malia where I turned south again toward the sea. The run toward the coastal road passes the Sanctuary of Aphrodite, set amid orange groves on rising ground enjoying a cool breeze from the sea, sometimes known as Old Paphos. It was once one of the most popular places of pilgrimage in the ancient world right up to Roman times. In its heyday the temple would have dominated the seaward approach to the south coast. I wonder what stories its few remaining ancient stones could tell witnesses to over 2,000 years of history, and what they would say of the British.

‘Cyprus should be Greek there is no doubt about it,’ Michael, one of the locals told me near Pissouri Bay where I had gone in search of food. But Michael was not as local as all that, for his tall frame, fair skin and blonde hair betrayed his background: Athenian by birth, Cypriot by marriage.

‘I was a paratrooper in 1974 ready to come and fight for Cyprus. But you English let us down. Not you personally, it was your weak politicians,’ he hastily added. For ‘philoxenia’, the law of hospitality, would not allow an insult to a stranger. I pointed out the Greeks had broken the tripartite agreement of 1959 and had given the Turks the legal right to intervene. And from the north coast Cyprus was only 40 miles from Turkey. Surely the geographic position of the island made it as history had demonstrated a crossroads of the Middle East rather than just another Greek Island.

‘You English,’ he said smiling, ‘history for a Greek goes back through his family hundreds of years. And the Turk,’ he said, contorting his face as if there was a bad odour in the air, ‘have been about only a few years compared to us. Did you know [I did not at the time] the whole of the Middle East was Christian for centuries before the Turk who are just Mongol barbarians my friend. Goodbye English,’ said Michael as we parted. ‘Do not worry about the history it is hard enough for us.’

Surely Michael, it seemed, was guilty of a familiar misconception Penelope Tremayne had identified so well: ‘Cypriots are Greeks, but Greeks are not Cypriots.’7 However, his words did put a thought in my mind: had we the British, as Michael had hinted, somehow betrayed the legacy of Hellenism with our actions on Cyprus, and in a way betrayed our own roots?

Patrick Leigh Fermor came across the same question in his travels in the Peloponnese, that England had let the Greeks down and even more somehow turned Turk against Greek on Cyprus. He wrote in 1958:

The conviction that its emergence ‘inter-communal fighting on Cyprus’ was fostered by Great Britain to bring in outside support to an otherwise untenable case has done more than anything else to embitter the problem in Greece.8

I crossed again into the SBA near Paramali, another Turkish village deserted now, except occasionally for squaddies on exercise. Its mosque and Muslim cemetery are identified by a sign asking people to respect its sanctity.

Near the entrance to the Sanctuary of Apollo I was pulled in at a Ministry of Defence VCP manned by MOD (Ministry of Defence) police who were locals working for the British. How things have changed. Badly I tried to explain I had seen Frankie Howerd entertain the troops here at the Greek theatre overlooking the sea in 1974, with a pop group, the name of which escapes me. But the police were more interested in my passport and driving licence and probably thought another ‘rambling mad weighty John who has been in the sun too long’. Greek Cypriots tend to call all Englishmen John. But they smiled and nodded and said, ‘Have a nice evening.’

I was soon back at Kolossi Castle again. The cicadas were tuning up for the night. I recalled a Turkish family we had helped at the VCP; why they stuck in my mind I don’t know. They had arrived in a grey battered Austin A55 crammed with the entire family, from gran to babes in arms, the roof packed high with pathetic possessions tied on through the doors. One of the back tyres was flat, and the engine was badly overheating. When the ignition was switched off the engine, so hot, ran on and on with pre-ignition, then at last shuddered as if dying before finally stopping. I remember giving Spangle sweets to the children from our ration packs. We had changed the wheel on the old Austin for them, using a bottle jack from our own Land Rover, refilled the radiator and sent them on to the tented refugee camp in the SBA. It was the air of fear about them that stuck in my mind. Fear that we would not let them into the SBA and they would be at the mercy of the EOKA-B. Where they are now or even who they were I have no idea. They are surely in the north of the island having gone through the melting pot of history.

The deployment of 40 Commando Royal Marines to Cyprus in 1974 was unusual. The Commando was the spearhead unit in July and was flown out to reinforce the western SBA.On 20 July the advance party left Seaton Barracks, Plymouth, by road, for RAF Lyneham and Fairford and flew to Akrotiri where it came under the command of HQ 19 Airportable Brigade. The Commando’s main task, with 1st Royal Scots, the resident battalion in Akrotiri, to maintain the security of the SBA.

Although the Commando changed company positions several times during its first deployment the general pattern of operations was the same. The border of the whole SBA was covered by a line of overt OPS, sandbagged sangars and a series of VCP check points and road blocks.

After three weeks the situation seemed to have stabilised and the Commando was released and started to fly back to the UK. However, after two days the flight back was cancelled, with half the unit still in Cyprus, the rest back in Plymouth, some of whom had already gone on leave. However, the recall system was used again and the vast majority returned to Plymouth and then to Cyprus, to be greeted with. ‘Well did you enjoy your weekend leave in Guz?’, Guz being naval slang for Plymouth.

The recall was the result of the Turkish Army resuming its offensive on 14 August. What has been called Phase 2 of the Attila operation.

The Commando resumed its duties in the western SBA, and also helped in constructing refugee camps and clearing service married quarters and hirings in Limassol outside the SBA which had been the subject of some looting. It also helped with requests from the UN. It was in this same general area 40 Commando was deployed in 1955–56.

Notes

1. LTA, Squadron Leader C.A. Pomeroy, 10/6/2000

2. Globe and Laurel, Journal of the Royal Marines, August 1974

3. Colin Thubron, Journey into Cyprus, p. 151

4. Dr Ekaterinich Aristidou, Kolossi Castle through the Ages, pp. 43–4, and Tabitha Morgan, Sweet and Bitter Island, p. 57

5. Sir Harry Luke, Cyprus, p. 174

6. Daily Telegraph, 11/5/2000 and The Guardian, 21/5/2001 and David Matthews, The Cyprus Tapes, p. 7, ‘Annie Barrett telephoned from Kyrenia and called him “The butcher of Ledra Street”’.

7. Penelope Tremayne, Below the Tide War and Peace in Cyprus, p. 10

8. Patrick Leigh Fermor, Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese, p. 210

Cyprus General Map

1

THE EARLY YEARS

Benjamin Disraeli came back with Lord Salisbury from the Congress of Berlin in 1878 claiming ‘peace with honour’; they also had Cyprus in their pocket.

On 13 June 1878 the Congress of Berlin had convened to try to make sense of the Treaty of San Stefano, signed three months earlier after the fourth war of the nineteenth century between Russia and Turkey. Most delegates’ thoughts were on Russia’s further encroachment on Turkey’s European frontiers; no one thought much of the Middle East and even less of Cyprus. However, the senior British negotiator, the ambassador in Constantinople, Sir Henry Layard, had already done a secret deal for Perfidious Albion; on 4 June a ‘convention of defensive alliance’ was signed between Great Britain and the Ottoman Empire. So the Sultan Abdul Hamid II ceded the island of Cyprus ‘to be occupied and administered by England’. The role of Cyprus in this was to become Britain’s forward base to support Turkey against any further Russian aggression. Although the island was never suitable as a fleet base, Britain was willing to support the Ottoman Empire as a buffer against Russian designs on India.1

On 12 July 1878 Vice Admiral Lord John Hay hoisted the Union Flag in Nicosia and assumed the temporary administration of Cyprus from Bessim Pasha, its last Turkish governor. Ten days later Lieutenant General Sir Garnet (later Field Marshal Viscount) Wolseley landed at Larnaca with a force of British and Indian troops and took over the Government as the first British High Commissioner.

Then the only road on the island connected Nicosia and Larnaca but was in a poor state of repair. The British troops marched the 30 miles or so along this road from Larnaca, which partly crossed the Mesaoria Plain, a flat featureless cauldron of heat and dust to the south of the Kyrenia Mountains. Even in the 1950s Lawrence Durrell saw camel caravans crossing the ‘brittle and arid soils’ of the Mesaoria, more like a desert in summer.2

The locals must surely have thought how mad the British were to move about in the summer heat in red coats. Indeed one of the first, if not the first, squaddie to die on Cyprus lies buried in the English cemetery at Kyrenia. His tombstone reads:

Number 141 Sergeant Samuel McGaw, VC, 42nd Royal Highlanders died on the line of march to camp Chiftlik Pasha of heat apoplexy, 22 July 1878. Aged 40 years.3

McGaw from Kirkmichael in Ayrshire had won his VC in the Ashanti War on 21 January 1874 at the battle of Amouful where the then lance sergeant had ‘led his section through the bush in a most excellent manner and continued to do so throughout the day, although badly wounded early in the engagement’.4

Five years after his death the grave site at Chiftlik, where he had been laid to rest, was to be levelled so his remains were disinterred under the direction of Captain Scott-Stevenson, Commissioner of Kyrenia. This was reported in the Cyprus Herald of 17 June:

The remains were carefully placed in a shell and conveyed to Kyrenia; on the 12th inst. Captain Scott-Stevenson in the full uniform of the Black Watch followed the remains of this gallant soldier to the little cemetery above Kyrenia and laid them beside those of his comrades who died there. The shell was covered with the British Flag and carried on the shoulders of six Turkish Zaptiehs. After the internment Mrs Scott-Stevenson decorated the grave with wreaths of passion flower and jasmine. A suitable monument will be erected by the desire of the officers of the Black Watch.5

The city of Nicosia in 1878 was still largely confined within the Venetian walls of the town, a little over 2 miles in circumference, in a circle, with eleven equidistant great heart-shaped bastions. The original Crusader walls had been much longer but the Venetians had destroyed these to make the defence line shorter. When the Union Flag was raised over the city in July 1878 it was not the first occupation of the island by troops from the misty shores of Albion that had taken place over 600 years before.

Richard I Coeur de Lion, the Crusader king known as ‘the Lionheart’, conquered Cyprus in 1191 in a three-month campaign and established there a base of operations for the Christian forces in the east. Richard sailed for the Holy Land during the Third Crusade 1189–92. His fleet of 200 ships left Messina, Sicily, on 10 April but heavy storms forced them to seek shelter. Most went to Rhodes, but four were blown toward Cyprus, two being wrecked on the coast near Limassol. One of them carried the king’s fiancée, Berengaria, and his sister Joan, but this ship, although battered, managed to anchor off the coast.

The ruler of Cyprus, Isaac Komnenos, ordered his men to capture the shipwrecked survivors. Isaac had no liking for the Latins and had an understanding with Saladin to deny his ports to the Crusaders. He attempted to lure Joan and Berengaria ashore hoping to hold them to ransom; when that failed, he withheld fresh water.

On 6 May Richard arrived at Limassol with the bulk of his fleet. He soon demanded the release of his people. Isaac rejected the demand following which the Crusader army landed, occupying Limassol. Three days later the two men met at Kolossi to try to settle things peacefully. It was agreed that Richard should abandon Cyprus while Isaac, for his part, would support the Crusaders financially and with men, and the island would help provision the army. But as soon as Isaac realised Richard’s force was small he reneged on the deal and demanded the Crusaders leave Cyprus or face battle. Isaac’s actions were not that uncommon for the times but had he known Richard better he might have come down on the side of caution.

Angered by Isaac’s treachery Richard landed his army and advanced toward Kolossi village where the enemy were camped. In the battle Isaac’s forces were defeated and he fled to Nicosia. Richard returned to Limassol, where on 12 May he married Berengaria in the Chapel of St George in Limassol Castle. At the same ceremony Berengaria was crowned Queen of England, and Richard, rather prematurely, was crowned King of Cyprus. While in Limassol, Richard met the deposed King of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan, and the two became allies.

Richard of legend, a brave, chivalrous knight and fearless soldier, was, as far as we know, in reality somewhat different. He was a good soldier, but also boorish, sadistic and greedy. Richard I was crowned in England at Westminster on 3 September 1189 and immediately set about raising money for the Crusades. He sold castles, manors, privileges, public offices, even towns and is said to have remarked: ‘I would sell London, if I could find anyone rich enough to buy it.’6

The campaign Richard undertook to conquer Cyprus was short and decisive. He marched east along the south coast from Limassol to Kiti near the Salt Lake and from there across country to Famagusta, which fell without a fight. Then he turned west toward Nicosia. Richard ran into Isaac’s main forces at Tremethousha, midway between Nicosia and Famagusta. After a fierce but brief fight, Isaac’s force was overwhelmed. Guy de Lusignan, commanding the fleet, captured the castle of Kyrenia from the sea and imprisoned Isaac’s family, who had been sent there for safety. Guy passed east along the coast to the castle of Kantara where he found Isaac and captured him.

Kantara is the best preserved of the three castles that dominate the Kyrenian mountain range, the others being Buffavento and St Hilarion. All were later largely dismantled to various degrees by the Venetians. From Kantara’s walls 2,000ft above the sea one can see both coasts of the Karpas Peninsula, Famagusta Bay, and even the Turkish coast. Given the remoteness of these castles, Richard’s campaign to subdue the island in a month is impressive.

At the Apostolos Andreas Monastery that lies 4 miles from the tip of the Karpas Peninsula, later called the Pan Handle by British troops, Isaac was brought before Richard, whom he begged not to be put in irons. Richard agreed and had him put into silver chains and taken to Palestine, where he died in squalor in the dungeons of Castle Margat near Tripoli in 1195.

Richard’s enforcement of the feudal laws of conquest upset the locals straight away when he took half their land and gave it to his knights. On 5 June he sailed for Syria, leaving a garrison to hold the island. However, it soon became obvious after a Cypriot revolt that Richard did not have enough men to hold Cyprus. So rather than take men from other fronts he used another favourite tactic of his and sold the island. He sold Cyprus to the Knights Templar who paid 40,000 gold bezants as a deposit while the balance of 60,000 would be paid yearly by instalments. So Cyprus, Richard hoped, would become a nice little earner.7

The Templars had equal trouble with the locals and they sold Cyprus on to Guy de Lusignan, Richard’s old friend. With better treatment of the locals it was the beginning of a long Frankish line, who would rule Cyprus for 300 years. One local, the hermit Neophytos in a letter ‘Concerning the Misfortunes of the land of Cyprus’, did comment on the first English occupation. He had no love for Isaac, ‘who utterly despoiled the land’. And as for Richard, he was no better: ‘the English King, the wretch, landed in Cyprus and found it a nursing mother. The wicked wretch achieved nought against his fellow-wretch Saladin but achieved this only, that he sold our country to the Latins.’ As for the Hospitallers, Templars, and other Franks, their ‘bandying’ of the island did it few favours.8

In July 1878 Sir Garnet Wolseley set up his first camp a mile west of Nicosia on what was thought as the traditional place of King Richard’s encampment. A prefabricated wooden military bungalow on its way to Ceylon was diverted at Port Said and became the first Government House on the same site.

Wolseley appeared to have had a burning dislike of foreigners, hardly a good attitude for the British governor, especially in a new land. He wrote in his diary for 16 August 1878: ‘What poor fools we English travellers are and how our open purse is made to bleed by the scheming villainy of all foreigners. I don’t like foreigners I am glad to say.’9

On the 18 August he went to the official blessing of the Union Jack in the cathedral in Nicosia, where he found the clergy to be ‘dirty greasy priests’. Also it was a long service which did not improve Wolseley’s humour:

at last the Abbot stepped forward and took the British Jack from the table where it had been lying while these incantations were being gone through and incense being burnt over it. As if our flag required any purification – and opened and fastened it to the halliards and it was hauled up amidst loud ‘Zita’s’ from the ugly crowds. Cheers were given for the Queen and, the ceremony over, went back to breakfast.10

This should have been an honour to have the flag blessed in this manner and shows Wolseley at his worst. He did in general dislike all priests, Anglican’s just as much. However, he quickly identified that Turkey had financially ruined Cyprus:

He (being the Sultan) takes all the plums out of the island, throws upon us the responsibility of governing it well, which means large expenditures, while he reserves to himself the power to sell three-quarters of the whole area of the island and insists on our paying him a large sum annually as a rent for the estate he has ruined.

By September 1878 he was informing Lord Salisbury that the £103,000 the Grand Vizier expected annually for Cyprus was ‘simply ridiculous to think of paying such a sum’. But if this was reduced to ‘£100,000 we should do very well here as long as nothing was charged against us for Military expenses’.11 In fact, the British garrison had been suffering considerably and was causing Wolseley some concern. On 17 August he wrote:

The thermometer in our camp stood at 110 degrees FAH, in our hospital morgue. What must it be like in a bell-tent? A bell-tent is next to useless here. The west winds are most trying. We have now about 18 per cent of the Europeans in hospital with fever. Which is not however of a very bad description. One of the sappers, here in hospital shows signs of typhoid his tongue being black and foul.12

At the time many theories were put forward on the causes of the camp fever. But it was not until 1898 that Sir Ronald Ross identified the malaria-carrying mosquito as the culprit, which bred in their millions in the marshes surrounding the coasts, particularly around Larnaca and Famagusta. It would not be until 1948 that the marshes were drained and Cyprus was declared free of malaria. Wolseley did have the sense to move most of his troops to camps on higher ground where the winds were fresher and away from Nicosia: ‘for I am sure if we remained in it we should all suffer; it is one great cess-pit into which the filth of centuries has been poured’.13 Queen Victoria even took a personal interest in the welfare of the troops suggesting sending the men to sea for a cruise to improve their health.

Locusts had plagued Cyprus for centuries before the British arrived. In 1355 the Italian Villani wrote:

At that time the locusts were so abundant in the isle of Cyprus that they covered all the fields to the height of one-quarter braccio and ate everything green on the earth and so destroyed [the farmer’s] labour that there was no fruit to be had in that year.14

In 1590, Tomaso Porcacchi of Venice wrote of his visit:

Cyprus suffers yet another plague, that now and then a certain insect infests it. About every third year if the seasons are dry, they grow slowly in the likeness of locusts, and in March being now winged and as thick as a finger, with long legs, they begin to fly. At once they come down like hail from heaven, eat everything voraciously and are driven before the wind in such huge flights that they seem dense clouds.15

A hundred years later the Dutch traveller Cornelis Van Bruyn on the island observed the locusts around Famagusta ‘… were like a dark cloud through which the sun’s rays could scarcely pierce’.16 Hamilton Lang, the British Consul in Cyprus, wrote in 1870 that Mehmed Said Pasha had virtually managed to wipe out the locusts with the help of Richard Mattei. Mattei was an Italian who had settled in Cyprus where he owned a prosperous and well-run farm. Garnet Wolseley had met him in 1878; he likened him to Count Fosco in Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White but felt the wine from his farm was amongst the best on the island.

Wolseley was glad to have him on his unofficial council, and to use his experience in using traps to eradicate the locusts, which sadly had returned due to Government negligence in the past five years.17 And so the traps were soon in use again. Lieutenant Donnisthorpe Donne of the Royal Sussex Regiment serving with the Cyprus police in the spring of 1882 was on trap inspection duty:

The Locust campaign was now fairly well started and these pestivorous insects were now appearing in alarming quantities and every day increasing in size and developing their destructive qualities. I was ordered out again on the 21st March by the Commissioner on a round of inspection embracing all the traps in the Nicosia District which took me a week riding round. Throughout the Mesaoria plains stretching from the Carpas to Morfu on the North, there were altogether in use upwards of 140 miles of traps and screens! This astonishing length will give some idea of the work in hand.

The screens were of canvas bound with oilcloth at the top and about 3 ft high, the oilcloth over which the animals could not crawl obliging them to crawl along the canvas until they happened into the pits prepared for their reception. These pits were dug at right angles to the screens at intervals of about 20 yards, being likewise lined with zinc, preventing the locusts from climbing out again.

In whatever direction the locusts appeared to be advancing therefore, were the traps and screens erected to intercept them. In this manner vast multitudes were destroyed. In Timbo, Morgo, and Piroi the locusts were passing the Larnaca road in countless myriads filling the traps to overflowing. The streams were all full of them: the country was all black with them, such an extraordinary sight did they present.18