8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

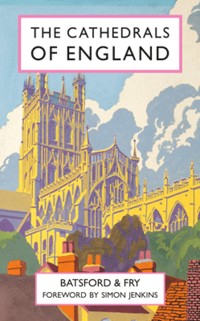

The companion reissue to The Spirit of London, this classic text from 1934 is still an invaluable aid to understanding England's cathedrals. It aims to give a brief account, and pictorial review, of each cathedral in England. Simply and concisely written to be read by anyone with an interest in the subject. From mighty York minster, Durham and Canterbury through St Albans to Ripon and Southwark, all the cathedrals are covered. The full list of cathedrals covered are: Bristol, Canterbury, Carlisle, Chester, Chichester, Durham, Ely, Exeter, Gloucester, Hereford, Lichfield, Lincoln, London, Norwich, Oxford, Peterborough, Ripon, Rochester, St Albans, Salisbury, Southwark, Southwell, Wells, Winchester, Worcester, York. Also the Parish church cathedrals of Birmingham, Blackburn, Bradford, Chelmsford, Coventry, Derby, Leicester, Manchester, Newcastle, Portsmouth, St Edmundsbury, Sheffield and Wakefield. Not only does it have the stunning Brian Cook illustration on the cover (Gloucester Cathedral), but several of Brian's line drawings are used inside the book. A beautiful book to have on any shelf, this is also a practical guide that still works as a reference guide. It should be stocked in all the cathedral shops across England! The companion reissue to The Spirit of London, this classic text from 1934 is still an invaluable aid to understanding England's cathedrals. It aims to give a brief account, and pictorial review, of each cathedral in England. Simply and concisely written to be read by anyone with an interest in the subject. From mighty York minster, Durham and Canterbury through St Albans to Ripon and Southwark, all the cathedrals are covered. The full list of cathedrals covered are: Bristol, Canterbury, Carlisle, Chester, Chichester, Durham, Ely, Exeter, Gloucester, Hereford, Lichfield, Lincoln, London, Norwich, Oxford, Peterborough, Ripon, Rochester, St Albans, Salisbury, Southwark, Southwell, Wells, Winchester, Worcester, York. Also the Parish church cathedrals of Birmingham, Blackburn, Bradford, Chelmsford, Coventry (pre-war building), Derby, Leicester, Manchester, Newcastle, Portsmouth, St Edmundsbury, Sheffield and Wakefield. Not only does it have the stunning Brian Cook illustration on the cover (Gloucester Cathedral), but several of Brian's line drawings are used inside the book. A beautiful book to have on any shelf, this is also a practical guide that still works as a reference guide. It should be stocked in all the cathedral shops across England!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 245

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE CATHEDRALSOF ENGLAND

By

HARRY BATSFORD

Hon. A.R.I.B.A., and

CHARLES FRY

With a Foreword bySIMON JENKINS

Illustrated from Drawings byBRIAN COOKand from Photographs

FOREWORD

By SIMON JENKINS

The loveliest sight in England is from the foot of the stairs to Wells Chapter House. It rises in lofty symmetry to a forest of shafts, arches and traceried windows, like a ladder to Heaven. Half way up the visual symmetry breaks, the steps divide and they swerve gracefully to the right, into the exquisite chapter house chamber. Stop, says the architect, at this point in the ascent, there are delights to be had still here on Earth. Come see them. I know of nothing so beautiful.

Ten years after Harry Batsford and Charles Fry completed their guide to England’s cathedrals in the 1930s, these places were considered doomed. A war-battered Church of England had to concentrate on reviving its parochial life and financing its clergy. Cities such as Bristol, Norwich, Durham and York had parish churches and to spare, all in desperate need of attention. Lesser centres, such as Ripon, Southwell, Ely and Wells, had no longer any use for places of worship of such size.

Even before the depradations of a bombing war, on a scale that Batsford and Fry could not have contemplated, the outlook for the cathedrals was grim. They were dinosaurs. The sense of reverential awe that infuses this guide might appeal to specialists. But what conceivable future could there be for these dinosaurs? They would have to pass to the state.

After the war Anglicanism continued to decline. The only area of growth was an evangelical movement with little time for churches, let alone cathedrals. In a lifetime of church visiting, I tired of hearing that “God’s house is not a museum” and that worshippers were not art curators. The church commissioners remained adamant. Their business is to buttress the clergy but not buttress the roof over its head. If the public wants to keep its cathedrals, then the public had better look to its own resources. Commissioners are not conservators.

The pessimists were wrong. What has proved most unexpected, indeed astonishing, is that the public has supported cathedrals both as places of a new sort of collective worship and as great art. Of all institutions of the modern Anglican church, those in the most robust good health are its cathedrals. As Chaucer reflected with surprise on how “longen folk to go on pilgrimages,” so we wonder at the appeal of cathedrals at a time when so much Christian worship is in decline.

England’s medieval cathedrals, and indeed its modern ones, have worked their way into the nation’s cultural consciousness largely independent of their function as religious shrines. They have been appreciated, locally, nationally and internationally, for what they manifestly are, one of the great art works of any age in any part of the world. Tourists appreciate them. Fundraisers love them. Support has also flowed to monastic structures that did not survive the Reformation settlement as cathedrals, and therefore do not feature in this book, such as Westminster, Selby and Tewkesbury. That the small market town of Beverley in Yorkshire might support not one great church but two is remarkable, yet it does.

The reason is plain from this book. Works that the Middle Ages erected to the glory of their God are appreciated today as glories of the Middle Ages. From Durham’s stupendous arcade to the serene Perpendicular of York Minster, from Lincoln’s lierne vault to the exuberant humanity of Exeter’s bosses, from the intricate foliage of Southwell’s capitals to Ely’s majestic lantern, cathedral architecture and carving attained a quality unmatched down the centuries. Even visitors with little understanding of these arts cannot fail to gasp at the sight of Winchester’s nave or the muscular strainer arches at Wells.

Glancing through these pages revives old controversies. Black and white pictures focus the eye on architectural form, undistracted by colour. The Romanesque nave at Peterborough undoubtedly has an austere dignity in monochrome. It is also intriguing to see old St Paul’s in its uncleaned state, its portico gaining in depth and contrast. But I am reassured in preferring my cathedrals relatively scrubbed. The mattblack appearance of a gothic exterior, doused in coal dust, may carry a romantic patina of age for some, but it looks sooty and Victorian.

One happy consequence of the cathedral revival is restoration. Batsford’s churches look dark places, as if sliding back towards the ruination in which the 19th century found them. Today they seem happier crowded places. While many, indeed most, local parish churches have been starved of attention and embellishment, cathedrals have taken on many of the civic and cultural functions they had before the Reformation. They are home to charities, regiments and guilds. They are used by schools and colleges: Canterbury is a glorious venue for Kent University degree ceremonies. Cathedrals are among the finest concert halls in the country. Their music schools are full and their choirs perform and record nationwide.

These places have rediscovered their place in the community and reasserted their primacy as beacons of England’s religious, civic and cultural life. They are museums of all the arts without compare. This book is their worthy celebration.

SIMON JENKINS, 2011

PREFACE

This book is intended first and foremost as a compact pictorial review of the Cathedrals, with a brief account of each, written as simply and concisely as possible to meet the needs of the increasing body of people who appreciate these great churches, and are now, with the development of touring, able to visit them much more frequently and. widely. It is, of course, a large and fascinating field of study, capable of treatment from many angles and in almost infinite detail, and has furnished the subject-matter of quite a library since John Britton completed his great twelve-volume survey just over a hundred years ago. In fact, it may even be questioned whether any conspicuous need exists for yet another book: to which the answer is that, while the present volume cannot claim to provide more than a brief introduction on broad lines, most of the better works, such as Professor Prior’s Cathedral Builders and Francis Bond’s handbook, are out of print and no longer generally available, while in any case nearly all are planned on the generous pre-War scale that precludes reissue at a cheap price.

This book can, however, claim to illustrate the Cathedrals, if not in great detail, with all the resources of modern photography, with its transformed technique of lighting and effect. Actually there is in this office illustration material for an infinitely more comprehensive survey, that it only needs a measure of public support to produce; and since no such work has been published in England since Britton’s time, it seems a pity that so fine a photographic documentation cannot be made available in some form or another without a prospect of financial loss. In any publication of the present size and price, it is naturally impossible to do full justice to the wealth of craftsmanship that the Cathedrals contain, but if the pictures provided awaken any new interest, or prompt people to go out and look at the originals for themselves, something will certainly have been achieved.

For the sake of completeness, the recent “parish-church cathedrals” have been very briefly included, though theoretically outside the scope of the survey, and a short Glossary of terms has been appended, which, though necessarily incomplete, may be of assistance in elucidating certain unavoidable technicalities. The drawings in the text have inevitably, in many instances, been submitted to severe reduction, in order to fit the space available in the description. Plans are given in the case of every ‘major’ cathedral, and these are reproduced to a uniform scale of 100 feet to the inch throughout to make comparison easy.

The excursions in connection with the book have covered many hundreds of miles, and we owe much to the patience and courtesy of the cathedral vergers who have led us conscientiously over roofs and up towers, along the dark ridge-passages of vaults and the giddy footwalks of triforiums and clerestories. The letterpress has had the privilege of a critical perusal by Mr. F. H. Crossley, F.S.A., whose valuable and caustic notes have been incorporated throughout, most particularly in the sections on Chester, Durham and Exeter. The section on St. Paul’s has gained much from the suggestions of Mr. Gerald Henderson, the Sub-Librarian and Archivist of the Cathedral, and Mr. Aymer Vallance, F.S.A. has given us the benefit of his kindly advice on a number of difficult points. Finally, Mr. Edward Knoblock must be thanked for the practical expression of his interest.

H. B.

C. F.

April 1934.

THE DOUBLE-BRANCHING STAIR AT WELLS

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

The contents of this book is a faithful facsimile of the original 1934 text except for the new foreword by Simon Jenkins. As such, it includes the phraseology of the time, descriptions of England’s cathedrals of the time, and also attitudes of the 1930s. We hope that this has a charm and interest all of its own, but wish to remind readers that some of the information in the book is now considerably out of date and also that some of writers’ opinions are not shared by the Publishers, and no offence is intended. In particular we would like to mention that the authors discuss the pre-war Coventry cathedral that was destroyed in November 1940 during the Second World War bombing, and any reference to the last century is the nineteenth century.

Historian and artist Hubert Pragnell has kindly checked the text and below highlights those dated and/or incorrect pieces of information in the book.

Canterbury Cathedral, here ‘The roads approach through medieval gateways’. Strictly speaking, there is only one medieval gateway over a road, the West Gate. However, the cathedral is approached on foot through the Christ Church gate c.1517.

Chichester Cathedral, here The plan shows the Library located in what is now the Lady Chapel. The Library was removed from the Lady Chapel during the Cathedral restoration in 1871.

Durham Cathedral, here Chapter House was extended to incorporate the eastern apse as one unit, not separate as in the plan used.

Gloucester Cathedral, here The wooden figure effigy of Robert of Normandy is no longer in the Quire. It was there from 1905–88 but then moved to the south ambulatory where it is now.

St Paul’s Cathedral, here ‘….present reredos…’. This was destroyed by a bomb on November 1940. It was replaced by a baldacchino or canopy of marble and gilded oak over the new High Altar, based on drawings by Wren, and completed in 1958.

Norwich Cathedral, here The Lady Chapel was rebuilt as a memorial to the fallen of the First World War and is not located on the plan provided.

Salisbury Cathedral, here ‘…the vault at 85 feet to the ridge line is the highest in England’. This is not so. Westminster Abbey vault is 101 ft above the pavement of the nave.

Coventry Cathedral, here The cathedral was, of course, destroyed by bombing in November 1940. The new cathedral was designed by Sir Basil Spence and completed in 1962.

Liverpool Cathedral, here ‘….well on the way to completion by the mid nineteen forties’. It was finished in 1978.

Guildford Cathedral, here The foundation stone was laid in 1936 but work was held up by the Second World War, and it was completed in 1961.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The publishers must acknowledge their obligation to the band of photographers whose work is reproduced in these pages, namely, Messrs. W. A. Call (The Cambria Series), of Monmouth, for Figs. 91, 95, 110; the late Mr. Brian C. Clayton, of Ross-on-Wye, for Figs. 12, 32, 34, 41, 57, 62, 63, 67, 82, 83, 85, 97, 101, 107, 108, 124; Mr. F. H. Crossley, F.S.A., of Chester, for Figs. 14, 15, 19, 31, 60; Messrs. Dawkes and Partridge, of Wells, for Fig. 109; Mr. Herbert Felton, F.R.P.S., for Figs. 20, 21, 26, 28, 71, 87, 90; Messrs. F. Frith & Co., of Reigate, for Figs. 4, 13, 24, 25, 30, 36, 46, 47, 80, 86, 105, 121, 123, 125, 131; Mr. W. F. Mansell, for Figs. 66, 73; Mr. Donald McLeish, for Fig. 61; the Photochrom Co., Ltd., for Figs. 22, 27, 37, 45, 81; Mr. Sydney Pitcher, F.R.P.S., of Gloucester, for Figs. 2, 10, 11, 54, 58; The Prussian Art Institute (Photo-Abteilung des Kunstgeschichtlichen Seminars), of Marburg-Lahu, Germany, for Figs. 44, 55, 94, 116; Mr. J. Dixon Scott, for Figs. 64, 120, 128, 129; Mr. Charles H. Stokes, of Exeter, for Fig. 51; the Rev. F. Sumner, for Figs. 89, 96; Mr. Will F. Taylor, for Figs. 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 17, 18, 23, 29, 33, 38, 40, 43, 49, 50, 52, 56, 59, 65, 68, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 84, 88, 92, 93, 98, 99, 100, 102, 103, 104, 106, 112, 114, 115, 117, 118, 119, 122, 126, 127; and Mr. W. W. Winter, of Derby, for Fig. 130. Figs. 53 and 111 were kindly supplied by the Great Western Railway Co., and Fig. 132 by the London, Midland & Scottish Railway Co. Figs. 113, 133 and 134 are included by courtesy of The Times, The Builder and The Architect and Building News respectively, and the colour frontispiece is reproduced, by permission of the authorities, from an original in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD By SIMON JENKINS

PREFACE

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

INTRODUCTION: Builders and the Fabric

THE MAJOR CATHEDRALS

Bristol

Canterbury

Carlisle

Chester

Chichester

Durham

Ely

Exeter

Gloucester

Hereford

Lichfield

Lincoln

London

Norwich

Oxford

Peterborough

Ripon

Rochester

St. Albans

Salisbury

Southwark

Southwell

Wells

Winchester

Worcester

York

THE PARISH-CHURCH CATHEDRALS

Birmingham—Blackburn—Bradford—Chelmsford—Coventry—Derby—Leicester—Manchester—Newcastle—Portsmouth—St. Edmundsbury—Sheffield—Wakefield

THE MODERN CATHEDRALS

Truro—Liverpool—Guildford

GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED

INDEX

2 ANGEL PLAYING THE CITHOLE : Carved Stone Figure from the Vault of the Gloucester Quire

3 WELLS : The ‘Poor Man’s Bible’ of the West Front. A Plastic Framework for one of the finest displays of Medieval Figure-Sculpture in England

INTRODUCTION

BUILDERS AND THE FABRIC

In the history of art in Western Europe, the building achievement of the Middle Ages provides in many ways the most remarkable chapter. In this country, in spite of the antiquarian researches of over a century, the extent of its surviving monuments is still seldom realised; and though it is customary to blame the Reformation and the religious struggles it engendered for a terrible programme of destruction, the fact remains that by far the greater proportion are church buildings since adapted to the sedate requirements of Anglican worship. Of these, the English village churches form a record of simple unpretentious craftsmanship flourishing in country places and reflecting the deep religious impulse and social outlook of a medieval peasant people. The greater parish churches of the towns represent a more complex and ceremonial way of living, the pride of gild and citizen and the keen local patriotism of a small world of rudimentary communications. The cathedrals are of loftier conception, crystallising the power and dignity of a rich and ambitious Church, yet revealing almost in every stroke of the mason’s adze that latent other-worldliness inseparable from the workings of the medieval spirit.

The period of the Middle Ages can be reckoned arbitrarily as the thousand years that followed the collapse of the Roman Empire, roughly from 500 to 1500. A.D. For the first part of it, the spiritual currents of art and thought were feeble and intermittent, but from a phase of disruption and darkness a new building movement was evolved that took virile form in the so-called Romanesque style, which, fostered by the great Charlemagne at Aachen and the rising prestige of the Benedictine Order, began during the ninth century to spread itself gradually but impressively over Western Europe. Among the conflicting influences that worked on this youthful style, the old Roman tradition of the basilica, aisled and wagon-vaulted, was long maintained and developed, emerging as a logical and appropriate expression in round arcuated forms, which, despite a certain laboriousness in construction, was to hold the field for nearly four centuries with some magnificent achievements to its credit, a characteristic technique of ornament, and a powerful and vigorous school of sculpture. This style was introduced into England probably about a century and a half before the Norman Conquest, when many existing churches were rebuilt in stone. At first its practice must have been crude and provincial enough; at the same time it is a mistake to regard Saxon Architecture as other than a simple and more primitive version of the Anglo-Norman that superseded it, to which it had already been groping its way slowly under potent pre-Conquest influences from across the Channel.

Though in many cases their religious foundations date from several centuries earlier, the history of the English cathedrals begins with the Conquest, when the unprecedented building wave that had already clothed Northern France with its “white robe of churches” finally swept over England. The majority of the cathedrals have at least a Norman core. Some, like Durham, Norwich and Peterborough, represent to all intents and purposes a Norman-Benedictine fabric, little altered at later periods, while others, as Exeter and Winchester, though rebuilt or transformed, still largely adhere to their Norman planning and proportions. By the middle of the twelfth century the style had reached its zenith in this country; but its maturity was short-lived. Already in the Île de France new tendencies were growing apparent that threatened to revolutionise previous architectural conceptions, and these, under the direction of a great creative innovator, the Abbé Suger, were crystallised in the new church then building at St. Denis, of which the consecration took place in 1144.

Northern France was the birthplace of Gothic Architecture and the Île de France its cradle. The innovations of St. Denis ran like wildfire through the small capital province, and there is nothing in history to compare with the mood of popular exaltation which, during the next eighty years, produced in superb sequence the cathedrals of Noyon, Sens, Senlis, Notre Dame de Paris, Laon, Bourges, Chartres, Rheims, Amiens and Beauvais. The new vernacular spread triumphantly through France, into Spain, Germany, England, and even as far afield as Cyprus and Sweden. For a generation nurtured on pastiche and revival, it is hard nowadays to realise the absolute unanimity of such a movement, and the spell that its productions cast over the popular imagination—a spell that remained potent until the first breath of humanism came to dissolve it like a mist that still clung reluctantly to the hollows. Gothic was first and foremost a folk art, expressing the physical and spiritual needs of a feudal and intensely religious people, and influenced by such powerful contemporary forces as Chivalry, the Gilds, and above all the majesty and ritual of the Church. Romantic and insistently linear in character, it was in its essence the art of the North, which, to some extent through the agency of the Crusades and of the cult of pilgrimages, had absorbed and utterly assimilated a group of complex Eastern influences; and it is a commonplace that it held the memory of the early forests. It was an art of craftsmen, not of aestheticians, an art that reached to uncanny heights of technical mastery through the heavy routine of bench and lodge, achieving at its summit a remarkable fusion of structural and spiritual aspirations. Constructionally it represented the spirit of collective adventure and exploration; its failures were crushing, its successes triumphant. It would never have admitted the psychology of small men bickering over Vitruvian precept; its master-craftsmen were grand extemporisers, but content by the canons of the times to work in anonymity, while the Church, the King or the patron took credit for the achievement.

And as an achievement it was staggering enough. It often seems as though the builders had actually competed in structural experimentation, aiming one beyond the other at an ever more emphatic verticality, an ever more daring economy of material; an ever vaster area for their lovely expanses of window, webbed with stone traceries and heavy with solemn colour. The introduction of the pointed arch brought into being the ribbed stone vault, its members gathered like sheaves into slender shafts rising through the three main storeys, its thrust counteracted on the outside by a scaffolding of flying buttresses, themselves steadied by a wealth of pinnacles. These, with the array of gables, tabernacles and buttresses with which the churches were literally clothed, produced an utterly new effect of fretted intricacy, beautiful from most aspects and perhaps most particularly in the bold semicircular sweep of the apse to eastward, rising superbly above its chevet of small chapels. But for the ordinary medieval man and woman, the chief wonder of the new cathedrals would be the sculptured caverns of their triple porches, with their range upon range of calm statues which seemed to breathe something of St. Bernard’s quiet mysticism, a new spirit of gentle faith and solace far removed from the demonomania and threatening austerities of their Romanesque prototypes.

With the intimate connections between England and the Continent under the Angevin kings, it was inevitable that the germ of the new movement should develop rapidly in this country. Yet the evolution of Gothic in England was by no means identical with that of the Île de France, nor for that matter, in the early stages, was it comparable with it. At first only tentative local experiment followed the whole-hearted metamorphosis that was in progress across the Channel, and it was not until the opening years of the thirteenth century that English Gothic established itself as a consistent national architecture, from thence developing independently on its own lines until in its last long phase it emerged under its true colours as an utterly vernacular style, without Continental parallel or precedent. The chronological nomenclature of this architecture remains a vexed subject; and while no entirely satisfactory system has been produced, that of Rickman, with its six divisions based on the styles of window tracery, still seems, despite its obvious limitations, the most practical for ordinary purposes. Actually, of course, it was a continuous and living growth, with intermittent phases of activity and maturity, and its classification by ‘periods’ is bound to produce a slightly artificial impression. Nevertheless, these descriptive labels have their value if used circumspectly and within limits, and a classification by centuries is often far less satisfactory, if only in view of the gamut of change that most of them witnessed.1

The provenance of the cathedrals as they stand to-day is also rather complex and confusing. Nine of the pre-Conquest sees (Chichester, Exeter, Hereford, Lichfield, Lincoln, London, Sarum, Wells and York) were served at their seats by secular canons; and to these were added after the Conquest the great abbey churches of Canterbury, Durham, Ely, Norwich, Rochester, Winchester and Worcester, each with its quire of Benedictine monks, but containing, by an arrangement little known outside England, the throne of a bishop. Carlisle Cathedral was served by a foundation of Augustinian canons, and at the Reformation, the Augustinian churches of Bristol and Oxford were also promoted to cathedral rank, with the Benedictine abbeys of Peterborough, Gloucester and Chester. The great churches of the Cistercians, however, fared less fortunately at this period, for, by the rigid constitution of their Order, all were built, like Fountains, Rievaulx and Byland, in remote places, and were thus unsuited for conversion even into parish churches. The ruin of their austere Transitional architecture is one of the major tragedies of English building. The remainder are of comparatively recent establishment, and form a heterogeneous collection of abbey, collegiate and parish churches, though in two notable instances, Southwell and Ripon, the buildings had already long been used as supplementary ‘bishopstools’ necessitated by the vast area of the York diocese.

Similarly the fabrics, as will be seen in subsequent pages, form in the majority of cases a remarkable patchwork of building periods, sometimes piecemeal, and sometimes so incredibly composite that their dissection is a major and delicate operation. In certain of them, as Winchester, with its Perpendicular nave and Norman transepts, the contrasts are violent and abrupt; in others, such as Wells and Lincoln, there is a regular and harmonious gradation of styles, generally achieving its rich culmination in the eastern limb. Except in instances of clumsy patching and improvisation, which are not wanting, the effect, though often staggering to the foreign purist, is infinitely satisfying and delightful. In their diversity of form and detail, their calm aristocratic untidiness, the interiors elude description, and must be visited to be appreciated. Despite the vicissitudes of Church history, their wealth of craftsmanship is still almost inexhaustible; and together they form a vast and splendid memorial to some seven centuries of English labour in wood and stone.

* * *

The typical Benedictine abbey church built in England after the Norman Conquest was arranged on a consistent cruciform plan, evolved in line with the requirements of monastic worship. The long westerly limb was an aisled nave for the secular congregation, closed off from the monks’ quire by a stone pulpitum or screen. Beyond it, the transepts were often built with eastern aisles for small altars, and over the crossing was usually a low tower surmounted by a short conical spire. The eastern limb contained the stalls of the monks and the sanctuary of the high altar, and the church ended eastward in either a trio of apses or a semicircular processional ambulatory, with a series of radial chapels opening from it. Beneath the quire was a vaulted undercroft, or crypt, where the saints’ relics in the possession of the monastery were exhibited. The cloister was almost invariably on the sheltered south side, between nave and transept, with the monastic buildings grouped around it in an arrangement generally similar in its essentials to that of Durham, shown in the plan on here.

4 DURHAM : The Piers of the Nave—perhaps the finest example of the Anglo-Norman Building Style of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries

5 WELLS : The Nave Design of 1174. A magnificent early essay in Gothic Building by a West-Country School

Something of the strength and dignity of these interiors emerges in the photographs of the Durham, Norwich and Peterborough naves on Figs. 4, 35, 76 and 80. But their present severity belies the smooth perfection of their original finish with a thin coating of plaster over all, clothing them on the outside in immaculate white, and on the inside forming the basis for an elaborate scheme of mural painting in bright diapers and figure pieces cognate in style with contemporary manuscript illuminations. The little St. Gabriel’s Chapel in the crypt at Canterbury, the fragments of wall paintings that survive at St. Albans (89), Chichester and Winchester, and the great diapered ceiling of the Peterborough nave, recall something of the pristine beauty of this decoration. Nevertheless these churches, though built on an unprecedented scale, were on the whole reticent in carved ornament, of which their range was limited to a few motives, though the luxurious decadence of the Cluniac Order brought a new decorative richness into the work of the earlier twelfth century, little represented among the cathedrals, however, save in the working of individual capitals and of heavily sculptured door tympana, as at Rochester and Ely (page 36).

At the same time, as the century advanced, signs were apparent all over the country of an impending break with Romanesque formula, which, though long ignored with typical conservatism by the Benedictines, found expression in some interesting Transitional experiments of local schools, as at Ripon (page 77), Worcester (this as early as 1140) (page 104), and above all in the virile independent style employed by the conversi, or lay builders, of the Cistercian Order for their northern abbey churches of Fountains, Kirkstall and Furness. The precise currents on which Gothic Architecture was borne into England provide an obscure and controversial problem much beyond the scope of this book; but it is certain that its development must not be attributed to any single stream of influence, nor must it be forgotten that while a French master-mason was supervising the erection of the Canterbury quire, an English school of the West Country was working out its own interpretation of the same ideas in the nave at Wells (5). St. Hugh’s quire at Lincoln (circa 1190) provides at once the culmination of the Transitional phase of the twelfth century and the inauguration of the building programme of the thirteenth in this country; and it is significant that the favourite English use of Purbeck marble from the Corfe quarries for shafting and string-courses, clumsily employed at Canterbury, here achieves its first maturity.