105,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The classical tradition—the legacy of Ancient Greece and Rome—is a large, diverse and important field that continues to shape human endeavour and engender wide public interest. The Classical Tradition: Art, Literature, Thought presents an original, coherent and wide-ranging guide to the afterlife of Greco-Roman antiquity in later Western cultures and a ground-breaking reinterpretation of large aspects of Western culture as a whole – English-speaking, French, German and Italian – from a classical perspective. Encompassing almost two millennia of developments in art, literature, and thought, the authors provide an overview of the field, a concise point of reference, and a critical review of selected examples, from Titian to T. S. Eliot, from the hero to concepts of government. They engage in current theoretical debate on various fronts, from hermeneutics to gender.

Themes explored include the Western languages and their continuing engagement with Latin and Greek; the role of translation; the intricate relationship of pagan and Christian; the ideological implications of the classical tradition; the interplay between the classical tradition and the histories of scholarship and education; the relation between high and low culture; and the myriad complex relationships—comparative, contrastive, and interactive—between art, literature, and thought themselves. Authoritative and accessible, The Classical Tradition: Art, Literature, Thought offers new insights into the powerful legacy of the ancient world from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the present day.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1150

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title page

Copyright page

Figures

Plates

Prologue

Practical Information

Acknowledgements

Part I: Overview

§1: The Classical Tradition and the Scope of Our Book

§2: Mapping the Field

§3: Eras

§4: Sustaining the Tradition

§5: Authority and Authorities

§6: Masters of Knowledge

§7: Models of Style

§8: Beacons of Morality

§9: Love Guides

§10: Special Relationships

§11: The Visual Arts

§12: Popular Culture and Its Problematics

§13: Languages and Language

§14: Modes of Engagement

§15: Translation

§16: Science and Sensibility

§17: Looking at the Past

§18: The Classical Tradition – and the Rest

Part II: Archetypes

§19: Preface

§20: The Dome

§21: The Hero

§22: Word-Genres

Part III: The Imaginary

§23: Preface

§24: Myth

§25: The City

§26: Forms of Government

§27: The Order of Things

Part IV: Making a Difference

§28: Preface

§29: Originators

§30: Points of Departure

§31: Ideas and Action

Part V: Contrasts and Comparisons

§32: Preface

§33: Painting

§34: Political Thought

§35: Poetry

Epilogue

Bibliography

Supplemental Images

Index

This edition first published 2014

© 2014 Michael Silk, Ingo Gildenhard, and Rosemary Barrow

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Michael Silk, Ingo Gildenhard, and Rosemary Barrow to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author(s) have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Silk, Michael.

The Classical Tradition : Art, Literature, Thought / Michael Silk, Ingo Gildenhard, and Rosemary Barrow.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-5549-6 (hardback)

1. Classical literature–History and criticism. 2. Civilization, Classical–Influence. I. Gildenhard, Ingo, 1970- II. Barrow, R. J. (Rosemary J.) III. Title.

PA3013.S55 2014

880.09–dc23

2013028383

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

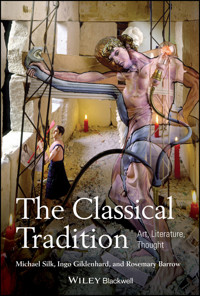

Cover image: Calum Colvin, Brief Encounter. By permission of the artist.

Cover design by Nicki Averill

Figures

1 Giulio Romano, ‘Jupiter and Olympias’

2 Nicola Pisano, pulpit detail (Hercules), Baptistery, Pisa Cathedral

3 Marcantonio Raimondi, engraving of the Apollo Belvedere

4 Flemish tapestry after Charles Le Brun, The Tent of Darius

5 Filippo Brunelleschi, Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

6 Forum shopping arcade in Caesars Palace, Las Vegas

7 Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat

8 Chris Gollon, Venus (I)

9 Thomas Gordon Smith, ‘Vitruvian House’

10 British Library piazza, London

11 Giorgio de Chirico, The Soothsayer's Recompense

Plates

1 William Blake, Albion Rose (Glad Day): see §3

2 Francesco Xanto Avelli da Rovigo, maiolica dish representing the Laocoon: see §11

3 Calum Colvin, Brief Encounter: see §11

4 Nicolas Poussin, The Arcadian Shepherds: see §14

5 J. M. W. Turner, Modern Rome: Campo Vaccino: see §17

6 Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space: see §17

7 Claude Lorrain, Aeneas on Delos: see §25

8 Titian, Worship of Venus: see §33

9 Jacques-Louis David, Paris and Helen: see §33

10 Giorgio de Chirico, The Uncertainty of the Poet: see §33

Prologue

During the writing of this book, colleagues who have enquired about the work in progress, and then learnt the title, have usually assumed that our collaboration must be intended to produce some sort of ambitious survey of classical receptions. What we are attempting is significantly different, but actually more ambitious: a rereading of a formative aspect of Western culture and, thus, a rereading, however partial, of Western culture itself in the perspective of the classical. Our scope is therefore wider, though our focus is certainly more coherent – but our potential readership is in any event more open-ended. We hope to appeal to a diverse readership among all who are concerned to make sense of almost two millennia of cultural developments and achievements, whether as advanced students, general readers, or fellow scholars; and if we have a particular hope, it must be that the outcomes of our efforts will be of serious interest to those with scholarly expertise across a broad spectrum of contemporary, modern, early modern, and medieval studies, along with the classics and its receptions, as well. We invite them, not least, to ponder the wider contexts into which we have placed their special concerns.

Although in various senses we do go ‘back to basics’, ours is not an introduction to the field. We do aim to offer an overview of the classical tradition, and a point of reference for a wide variety of different matters, but the book is not a survey, even if many of its sections do survey relevant material in whole or part. Nor is it a catalogue: we make no pretence to complete coverage of our field.

As we explain more fully in the opening section (§1), the book is a continuous work, and not a sequence of separate essays. It is not for us to dissuade readers from selective reading, but such readers should at least bear in mind that texts, works of art, topics, perspectives, may be presented in one section and presupposed in another.

We do not – let us stress at the outset – assume that the more classical is superior to the less, nor, indeed, that the less is superior to the more. If we assume anything, it is that a rereading like ours is as desirable as its subject is important.

If this was a research proposal, we would stress the extent to which we have sought to offer fresh appraisals of a wide range of material and to make new connections among a multitude of artists, writers, thinkers, works, and developments, well-known and lesser-known, that are not normally brought together in one volume, let alone in one (re)reading. Our ultimate concern, however, is with what is sometimes sceptically referred to as the grand sweep or the big picture. In today's academy, professional compartmentalization, allied to various strands of relativism (not least, postmodern suspicion of ‘metanarratives’), has encouraged a timidity in the face of such large readings which we see as, ultimately, absurd. Anyone who supposes they can do without grand sweeps or big pictures is deceiving themselves. Everyone relies on them. The question is whether it is enough simply to rely on them in the form of outdated surveys or, perhaps, fashionable critiques – or, instead, seek to improve on them. Assuming we have made some headway in that direction, however, we do not suppose that there can be anything definitive about any such improvement, and if our efforts provoke others to improve on ours, we shall be the first to applaud.

Ours has been a collaboration in the fullest sense of the word. Over a period of years, the co-authors have debated the contents, the arguments, the organization, and the minutest detail of the book, and while our respective spheres of special expertise have naturally helped to determine which of us produced an initial draft for which section, the fact is that every section has been redrafted several times, and that all three of us have contributed to every section as it now stands. The book has been a joint project, and we are, all three of us, committed to it, as a whole, in its final form.

‘Art, literature, thought’: we have sought to achieve a balance between our treatment of the three, not necessarily in quantifiable terms, but certainly in the sense that all three have been kept in view, as appropriate, throughout the book. ‘Thought’, perhaps, deserves a special comment. In our usage, the word in effect subsumes thought about antiquity, thought about art, thought about literature, and indeed thought about thought, as well as, for instance, specifiable aspects of cultural, ethical, and political thought; it would, however, be misleading to claim that technical philosophical or scientific issues, in particular, bulk large in our discussions.

Out of the many cultural traditions that have contributed to ‘the’ classical tradition, our concern (as we explain in §1) is primarily with four: the Italian, French, German, and those of the English-speaking world (in linguistic terms, this subsumes not only the corresponding four languages, but also post-classical, transnational Latin). In general, we have sought, once again, to keep a balance between our treatment of the four – but with one significant exception. Where close literary readings are called for, it will usually be literature in the English language that is to the fore – if only for reasons of simplicity of exposition and appropriateness for a readership whose common language is English.

Practical Information

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the following, for help with illustrations: Valentina Bandelloni and Alan Kirby, of the Scala Picture Library; Jacklyn Burns, of the J. Paul Getty Museum; Shelley Hales; and especially Calum Colvin, Chris Gollon, and Thomas Gordon Smith, for generously allowing us to reproduce their work; likewise to our respective universities for helping to defray the costs involved. We owe a debt of gratitude to Ian Wong for help with the index. Various friends and colleagues have read some or all of the book in draft: Matthew Bell, Antonio Cartolano, Terence Cave, David Hopkins, Deborah Howard, Sebastian Matzner, Rosa Mucignat. We offer them warm thanks for their comments and advice. We are grateful, too, for the helpful suggestions made by the publisher's readers and, not least, to Haze Humbert and the staff of Wiley-Blackwell, along with Graeme Leonard on the copy-editing side, for their efficiency and patience.

Michael Silk (King's College London)

Ingo Gildenhard (University of Cambridge)

Rosemary Barrow (University of Roehampton)

Part I

Overview

§1

The Classical Tradition and the Scope of Our Book

The classical tradition covers a millennium and a half of cultural achievements, historical developments, facts, fictions, and phenomena on many levels. It subsumes the many ways in which, since the end of classical antiquity, the world of ancient Greece and Rome has inspired and influenced, has been constructed and reconstructed, has left innumerable traces (sometimes unregarded), and has, repeatedly, been appealed to, and contested, as a point of reference, and rehearsed and reconstituted (with or without direct reference) as an archetype.

Interest in aspects of the classical tradition is currently as active as it is widespread. The classical canon may no longer dominate the modern mind, as it once determined the responses of elite circles in the past, but we live in a time when Hollywood blockbusters about ‘three hundred’ Spartans or the tale of ‘Troy’ attract enthusiastic audiences around the world, when innovative stagings of Greek drama are a familiar presence in many countries, when idealistic notions of, or anxieties about, ‘democracy’ continue to engender debate, and when the enduring tussle between Britain and Greece over the ownership of the Elgin (or Parthenon) marbles shows how cultural goods tied up with the classical tradition can still be a matter of high politics and national interest. These and countless other achievements, developments, and debates, past and present, are increasingly the focus of a miniature explosion in publishing and what is almost a new academic discipline in its own right.1 Various, often controversial, factors may have played a part here, not least the switch, within classical education in the English-speaking world, from language skills to ‘classics in translation’ (§§4, 15), but the level of interest in the classical tradition, both among the classically trained and across the arts and humanities, is beyond dispute.

What is ‘the classical tradition’? In contemporary usage, ‘classical’ and ‘the classics’ may mean a Beethoven symphony, the novels of Tolstoy, the films of René Clair – or a range of notable entities, from permanently-in-fashion dress designs to pre-quantum mechanics.2 For our purposes, ‘the classical’ means the world of ancient Greece and Rome, and ‘the classical tradition’ means reflexes of,3 uses of, reconstitutions of, or responses to, the ancient world from the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire to our own day. But – given that ‘classical’ has always had strongly positive connotations, and ‘tradition’, arguably, too (§2) – this entire domain is inevitably caught up in implications of value. For a start, it is not just any aspect of the Greco-Roman world that inspires and influences, but, overwhelmingly, the special and the privileged – Homer's Iliad, Plato's dialogues, the ruined glories of Phidias' marbles – even if the process of inspiring and influencing can sometimes seem to make the whole of antiquity special and privileged anew.

The classical tradition overlaps with the reception (or receptions) of Greece and Rome. They are not the same thing, and for several reasons.4 First, because the reception of Greece and Rome includes readings and rereadings from within the ancient world itself.5 There will be all manner of particular differences, but there is no necessary difference in kind or in hermeneutic status, between a response to Virgil's Aeneid from Virgil's own time, one from later antiquity, and one from a later age – say, T. S. Eliot's response, in a pair of provoking essays (§35). Yet though these are all instances of the reception of Virgil, only Eliot's essays can meaningfully be referred to the classical tradition. Conversely, the classical tradition is wider in scope. Many of its embodiments are not classical receptions in any meaningful sense. Post-classical versions of classical archetypes sometimes involve reception, sometimes not (§19). Equally, the Romance and Modern Greek languages are momentous post-classical reflexes of Latin and Ancient Greek, and as such clearly belong to the classical tradition, but they are not, in themselves, ‘receptions’ of anything. Whether the same should be said of Medieval Latin, and of Renaissance Latin too, is another matter; both, in any event, belong straightforwardly to the tradition.

Then again, the classical tradition, as a continuum, subsumes not only direct engagements with antiquity, but engagements with earlier engagements. Like Eliot, the poet Milton responds to Virgil's poetry; unlike Eliot, he responds not as critic, but by and within his own poetry, which – from Lycidas to Paradise Lost – creates (among much else) an idiosyncratic classicizing idiom that looks back to classical Latinity in general and Virgil's Latin among others. In this sense, Milton's poetic language represents a distinctive embodiment of the classical tradition; it is also the object of an Eliotian critique in a notable essay, which, however, makes virtually no reference to antiquity at all. That essay is eminently discussible as itself a critical contribution to the tradition and as significant evidence for Eliot's sense of his own distinctive place within it6 – but there is nothing in the essay to invite talk of ‘reception’ of antiquity, nor indeed is the essay commonly discussed as such.

Above all, though, whereas ‘classical’ and ‘tradition’ tend to prompt consideration of value, ‘reception’ does not. In a nutshell, the ‘classical’ of ‘the classical tradition’ tends to imply canonicity, even when the post-antique engagement with the antique is anti-canonical (as is the case, most obviously, with engagements within popular culture: §12). Indeed, notwithstanding the fact that it is precisely the value associated with the classical over hundreds of years that has brought its multiple receptions into being, reception studies tend to operate in a relativistic spirit, generally preferring cultural-historical engagement with such issues to critical engagement. All in all: reception studies have helped to make what was once the preoccupation of a minority of classicists, and others, fashionable – while reception theory has helped to generate better understandings of various aspects of the field – but in no sense has ‘reception’ itself been shown to redefine, let alone to replace, ‘the classical tradition’ itself.7

The scope of the classical tradition is vast. Its many continuities (and discontinuities) range from high culture to low, from politics to sport, from law to urban planning, from the Romance languages, and the Modern Greek language, to the international, largely Greek-derived terminology of modern science and the continuing use of botanical Latin names for plants – and not just by professional botanists, but by ordinary gardeners too.8 And if the scope is vast, the variety of usage that arises from particular points of reference is no less so.

Take Augustus and his age. Often regarded as (and seemingly regarding itself as) a ‘classical’ age in its own right, on the model of fifth-century Athens, with its sublimely assured art and architecture and public poetry, the Augustan age has in turn inspired classicizing revivals, along with other responses, in great profusion. It has bequeathed to the Western world the concepts of urban renewal in the grand manner9 and of ‘the classic of all Europe’ (Eliot on Virgil again: §35). And the ideals it has been taken to embody have been acclaimed and denied and reinvented, from Charlemagne and Alcuin (who relived the relationship between Augustus and his poets) to the Holy Roman Emperors (who retained ‘Imperator Augustus’ in their titles), from Cosimo I of Florence (who promoted himself as a Renaissance version of Augustus the autocrat, saving the state from the instabilities of republicanism) to John Dryden (founding father of the English ‘Augustan’ poets, who reconfigured the same historical schema in his youthful ‘Astraea Redux’, composed to celebrate the restoration of Charles II), from Joachim Du Bellay (who invoked ‘that most happy age of Augustus’ as a model for the emergent French aspiration towards a great language and a high culture) to Benito Mussolini (who commemorated his hero's 2000th birthday with a grandiose Fascist exhibition in 1937–8)10 to W. H. Auden (whose poem ‘Secondary Epic’ sniped from below at Virgil's lofty vision of Augustus as a carrier of destiny). In this example, and a host of others, it is hard to overstate the rich complexity of a tradition that has Greco-Roman antiquity as its unifying point of reference, but comprehends such a variety of forms and figures, social settings and relations, themes, media, and conflicting ideologies.

The range of our book, and the diversity of its connections and appraisals, reflects this ‘infinite variety’, but (we repeat) the book makes no attempt to take account of all possible points of reference, in topical, chronological, or geographical terms. While it contains its proper share of facts and figures, attested origins and unmistakable developments, our overall aim is an informed reading of the tradition that responds to diversity by making critical sense of it, and stimulates our readers to form, or sharpen, their own responses and assessments – perhaps in contrast to ours. Our emphasis is on art, literature, and thought: art, with more than passing attention to architecture; literature, with the same attention to theatre, opera, and film; thought, philosophy, and ideas, including, not least, ideas about, or associated with, art and literature themselves. Given the intricate relationships between literature and language, and thought and language, issues of language will impinge significantly on the discussion. So too will the interrelated histories of classical scholarship (§16) and education (§4), and also – interrelated again – of translation (§15). The ideological implications of the tradition will be a recurrent theme, as will the relation between high culture and low (we confront this directly in §12) and the related question of value.

Within art, literature, and thought, we have again made no attempt to scrutinize all media and all periods across all the cultures of the world. The classical tradition at its widest is a global phenomenon (witness Gandhi on Plato, Roman influences on the architecture of the mosque, the Greek-tragic evocations of the plays of Soyinka); and it has certainly been in constant dialogue with other cultural traditions throughout its history; but our discussion is concentrated on Western culture and, within Western culture, on the primary and closely related cultural traditions of Italy, France, Germany, and the English-speaking world.11 Among much else, this means that we have relatively little to say about Byzantium,12 which sustained the language, learning, and texts of Greek antiquity for a thousand years after the collapse of the Roman empire in the west, and which has considerable importance as a site of the classical tradition in its own right. Our focus is on the classical tradition in its undoubted heartland.

Within these limits, we seek to give a sense of the diverse contents of the tradition, but we are more concerned to ponder its coherence,13 delineate its profile, and explore its typology. In effect we are asking a series of questions about the tradition overall.

What is ‘the tradition overall’? How do we identify its boundaries? We confront this question repeatedly, especially in Part I of the book, from §1 (the present section) to §18.

What is its trajectory over time? Here, within the long march (or meandering) from late antiquity to the modern age, we give more than usual attention to the status of the eighteenth century as a transitional era, and to the Romantic generation as a turning-point (see, most immediately, §3 and §5). But the book is anything but a linear history, though many of its sections contain historical sketches.

What definitive forms does the tradition take? Reception, though itself a broad category, is only one such; and any answer to the question must take account, also, of reflexes (of which language is surely the most important: §13), of archetypes (§§19–22), and, as we have already pointed out, of engagements with earlier engagements (exemplified, representatively but not only, in §35). ‘Engagements’, in their considerable variety, we also categorize in different terms in §14.

What kinds of difference has the tradition made? This is a question we attempt to confront by placing the classical in and against the context of the non-classical. We do so both in large terms (§18) and by a focus on specific case studies (§§28–31). We also do so, more pervasively, by presenting the more ‘classical’, at any one time or place, as part of a less ‘classical’ whole. Our very different discussions of popular culture (§12) and Rome (§25) may be taken as representative here.

What kinds of relationship are there – comparative, contrastive, interactive – between the tradition in our four cultures? Between its embodiments in different periods? And (in some respects the most challenging question) between the art, the literature, and the thought of our title? – challenging, if only (though not only) because these three large areas of human creativity and endeavour are seldom brought together in any concerted way in contemporary understandings of the present or past, classical-related or other. These questions are not the kind that allow neat or simple answers, but we have had them in mind throughout.

And, not least, a question that arises directly from the others: what are the different ways in which the tradition can profitably be approached and understood? This question, along with the questions about relationship just cited, has determined the shape of our book. The body of the book is organized as thirty-five sections, of varying lengths, in five parts. Part I (§§1–18) is designed to represent an overview of the tradition and its diversity (this is outlined in detail in §2); Parts II–V present a series of closer readings from alternative standpoints: ‘archetypes’ (§§19–22), ‘the imaginary’ (§§23–27), ‘making a difference’ (§§28–31), ‘contrasts and comparisons’ (§§32–35).

In a more practical sense, considerations of diversities and alternatives have helped to determine the shape and size of the thirty-five sections. Some sections present their material at relative length, as with the important topic of language (§13). Others, much shorter, we offer as pointers for debate. Two in particular, §10 (‘special relationships’) and §18 (the classical tradition and other traditions), belong here – though in both cases the desire to avoid long lists of illusory counter-examples is also a factor. The shortest sections, designated as ‘prefaces’ to the several Parts that follow the overview (§§19, 23, 28, 32), seek to provide a theoretical framework for the different kinds of material, and different kinds of discussion, that follow them. But short or long, prefatory or discursive, every section is intended to contribute to a critical reappraisal of the tradition as a whole.

We use the word ‘critical’ advisedly. Any satisfying treatment of art, of literature, of thought, calls for critical judgement. Such judgement is exercised not least in the choice of examples, and here we are not just selective: we repeatedly argue from particular examples – a technique (this is no coincidence) most familiar in literary criticism. But in any case the classical tradition in these large areas is so implicated in value judgements from the past that any attempt at ‘impartiality’ now is likely to end up as a quaint evasion. Conversely, though, it may be acknowledged that in art and literature, in particular, achievement is not ‘superannuated’,14 and that there is a clear distinction between such areas and those where judgement now is largely superfluous and the classical tradition is a matter of essentially historical interest. The most obvious of the latter is the realm of scientific ideas, where a once common appeal to ancient authority – to the mathematician Euclid, to the medical expert Galen – has been superseded, since the age of Newton, by the dynamic of progressive discovery and the paradigm shift. Between the two extremes of art (visual or verbal) and science, what we are designating ‘thought’ tends to occupy an intermediate position.

In practice, our concern with critical judgement means attending, as sensitively as we can, not only to the variety of embodiments concealed within ‘the’ classical tradition, but also to the underlying presuppositions of our own discussion. This means that relevant issues are liable to impinge (they already have) as theoretical issues. For our explorations, theoretical perspectives are a prerequisite – as is a readiness to discriminate between, or beyond, them. Our discussions (or so we would like to think) are both theoretically informed and also actively engaged in current debate on a range of theoretical fronts, from hermeneutics to cultural studies to gender.

Notes

1 ‘New’, though ‘the classical tradition’ was identified as long ago as Victorian England (John Addington Symonds invokes, and contrasts, ‘Christian and Classical Traditions’ in his Renaissance in Italy: The Fine Arts, 1877, ch. 1), while it was formally institutionalized as a field of study in the Warburg Institute, first in Hamburg (from 1921), then in London (from 1934).

2 All, on different levels, authoritative. The association of ‘classical’ with authority is inscribed in its etymology from Latin ‘classis’ (‘fleet’/‘army’, as well as social ‘class’; cf. §3 n. 14) – as it is in (e.g.) the use of ‘classical’ architecture for buildings required to connote authority, from banks to museums. ‘Authority’: cf. §5.

3 We borrow – and extend – this use of ‘reflex’ from historical linguistics, where the word stresses the fact of descent without any implication of purposeful transmission or adjustment: ‘reflex … a word or other linguistic form which is directly descended within a particular language from an ancestral form taken as a reference point. For example … Italian donna “lady” is a reflex of Latin domina(m)’: Trask (2000) 278. In our extended usage, the word is reapplied from particular linguistic forms to whole language systems and other large behavioural structures. Thus, the Italian language per se is (largely) a reflex of Latin per se (§13), and medieval Italian carnival (partly) a reflex of ancient ceremonial or ritual (§12).

4 Compare and contrast e.g. Budelmann and Haubold (2008) and Caruso and Laird (2009) 2–3. See further §2.

5 Cf. e.g. Martindale (2006).

6 Milton, Eliot, and Virgil: §35.

7 Value: §§2, 18, Epilogue. Reception theory and the field: Martindale (1993), (2006).

8 In Britain, for instance, herbs like ‘salvia’ and ‘artemisia’ are as familiar under those names as under their English names, ‘sage’ (salvia officinalis) and ‘wormwood’ (artemisia absinthium). As these examples suggest, botanical Latin uses classical lexemes or word-shapes, but not necessarily according to the rules of classical Latin usage.

9 According to Suetonius (Augustus, 28), Augustus' proud boast was that ‘he found Rome built of brick and left it in marble’. Cf. §25.

10Mostra Augustea della Romanità.

11 Initially, but not of course exclusively, European. Here as elsewhere, recent scholarship seeks to take account of the marginalized and the peripheral (as, in conventional terms, they would be regarded), along with the canonical and the central: see e.g. Goff (2005), Goff and Simpson (2008), Hardwick and Gillespie (2007).

12 Our most significant omission besides is Spain (esp. significant in the Renaissance) and the Hispanic world.

13 Regarding this ‘coherence’, we note a revealing comment by the Nigerian playwright, Femi Osofisan, on his Women of Owu, an adaptation of Euripides' Trojan Women, first performed in 2004. His play addresses, not Western audiences (familiar, perhaps, with the Euripides), but ‘a Nigerian audience … the audience I am familiar with’: Budelmann (2007) 30. In a post-colonial perspective, there will be both new creativities to add to the old and new ways of reading the old, including the classical old: Euripides ‘reclaimed’ as ‘world literature’ is different from Euripides as part of the Western classical tradition.

14 Compare and contrast Eliot's refusal to ‘superannuate’ Shakespeare, Homer, or ‘the rock drawing of the Magdalenian draughtsmen’ (‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, 1920).

§2

Mapping the Field

The vast scope of the classical tradition, and the fact that at least until the nineteenth century it was so central to almost any cultural endeavour in the Western world that it was often taken for granted, explains in part why it lacks adequate disciplinary acknowledgement. Standard academic practice, applying the principle of divide and rule, chops it into chronological and geographical bits – Renaissance Italy, eighteenth-century France, German classicism, post-revolutionary America, Victorian Britain – for treatment by suitably trained experts. Such division of labour underwrites the modern knowledge industry, which favours specialization; but it cannot do justice to the classical tradition, one of whose hallmarks is precisely the way it spans nations and centuries, even though (to invoke a key tenet of reception theory) it is only ever ‘realized’ at a specific point in space and time.

At which point we might do well to pause and ask what constitutes a tradition as such – a question all the more urgent, given that common and critical understandings of the phenomenon tend to diverge. In everyday usage, ‘tradition’ carries connotations of longevity, or even invariance, in the reproduction and transmission of cultural practices or cultural goods. By contrast, scholars in various fields would agree that this fixity is at least in part a fiction – even if belief in its reality is a prerequisite for traditions to perform their ideological function for the social groups that sustain them. On critical inspection, any tradition will be seen to subsume continuity and change, stability and flux, repetition and innovation, though the specifics may vary greatly. There are distinctive oral traditions, which practise composition in performance and look to the legendary or timeless past, or else to the experience of recent generations (usually three generations) within ‘living’ memory.1 There are innumerable traditions of modest cultural practice, from specialized crafts to household activities to unwritten custom in everyday interaction. There are high-profile traditions rooted in ritual and belief, such as those that modern nation-states have fostered, or invented, to give their populations a historical identity.2 There are traditions centred on the transmission and exegesis of written, perhaps canonical, texts. There are artistic, literary, and intellectual traditions, perpetuated by artists, writers, thinkers, in dialogue with their predecessors, which might be said to limit – yet also, paradoxically, to facilitate – the originality of individual talents.3 And then there are fundamental traditions that give us our sense of meaning, of who and what each one of us is, traditions of practice and cognition that serve, if not to determine, then certainly to help shape, the specificity and identity of each human being as a being of culture, language, and history.4

Among traditions, the classical seems to be a special case, at least in the way we have defined it as made up of ‘reflexes of, uses of, reconstitutions of, or responses to, the ancient world’ (§1). To begin with, this is a tradition without an obvious owner. One can of course identify numerous individuals and groups who have engaged with aspects of classical antiquity and have thus invested in and perpetuated the classical tradition – while our own focus on the West, and on four cultures and languages within the West, might be said to suggest a certain kind of ownership itself. Even so, the sheer range of responses to antiquity, and the innumerable ways in which antiquity has outlived its chronological demise within art, literature, and thought, defy any attempt to establish clear proprietorship; even less so, once we bring into the reckoning the diverse realms of language and popular culture, education and scholarship, with which art, literature, and thought have been intimately, and very variously, connected; while in recent times, with the dissolution of a long-standing alliance between ‘the classical’ and ‘the elite’, the classical tradition itself has become unpredictably diversified, and has (perhaps) gained new vitality through its diversification.

The classical tradition is special in other ways too. Whereas many traditions serve to provide specific groups with a sense of their past and thus a sense of coherence in the present, the classical is ideologically diffuse: witness the fact that over the centuries recourse to antiquity has served a spectrum of national agendas and political movements, from the revolutionary to the established authoritarian, from the fascist to the democratic.5 Then too, this tradition has fed on the paradox that those who operate within it can do so by denying its premises. Where some have emphasized ‘legacy’, ‘inheritance’, ‘debt’, accumulated over generations, others, from Petrarch to Palladio to Nietzsche, have been prepared to brush aside the intervening centuries for a fresh encounter – perhaps a more ‘authentic’ encounter – with the ancient past. Indeed, one of the ideals, or fictions, that sustains the tradition is the holy grail of immediate, untraditional access to the ancient world and its creativity,6 the possibility of a privileged dialogical relationship that has helped to ensure the continual reshaping of antiquity itself in the image of the here and now. Much has changed – attitudes to the past and to tradition, not least – since the great Romantic shift around the end of the eighteenth century, but (say) de Chirico's fascination with the mythic Ariadne in the twentieth is, on a personal level at least, no less reflective of the dynamic than Petrarch's preoccupation with classical Latinity in the fourteenth.7 Conversely (to restate a point made in §1), the history of ‘the’ classical tradition abounds in instances where ancient texts and artefacts, ideas and ideals, have acquired new identities within other cultural traditions (developments intensified in recent years by the forces of globalization) – the upshot of which is a panorama of receptions, some of them remote from ‘our’ tradition altogether.

In the light of these variabilities, doubts may arise: is the phrase ‘classical tradition’ too limiting or else too contradictory to be useful? Some classicists, in any case, have criticised the notion on ideological grounds, playing off responsive, ‘liberal’, and active reception against a classical tradition conceived of as inherently monolithic, ‘conservative’, elitist, and caught up in the passive worship of past masters – though it is self-evident that a ‘reception’ can be passive too,8 while we have surely made it clear already that our understanding of the classical tradition is rather different. Others have queried whether the classical tradition can be discussed in a meaningful way as a whole, as if methodological propriety required us to limit our enquiries to the study of specific acts of reception. Coincidentally or not, in some languages there is no equivalent to ‘the classical tradition’; in German, for instance, the closest equivalents are Antikerezeption (a ‘reception’ word) and the paradoxical Nachleben (‘afterlife’), which has acquired some currency as a loanword in English, and which certainly captures the continuing vitality of classical antiquity (in the sense of its impact or influence) after its ‘death’.9

Against all these doubts, we insist on ‘classical tradition’ as a meaningful label and an essential critical concept. Not only is ‘reception’ too narrow a term to comprehend the full extent of ‘the’ tradition; it actually obscures the way that developments that are not receptions may themselves facilitate developments that are. Our example of language is once again paradigmatic here.10 In the study of Ancient Greek or Latin, as in the evolution of Ancient Greek into Modern Greek or the evolution of Latin into the Romance languages, the classical tradition has a powerful and pervasive presence beyond reception, but one which has repeatedly provided a crucial enabling condition for new engagements to emerge. The term, in fact, gives decisive shape to a crucial body of data, while the tensions between common and critical understandings of ‘tradition’ are surely one facet of the study of the classical tradition itself. We propose to continue to think with (but, if necessary, against) the notion in a theoretically informed way, rereading its historically accrued semantics, ideological functions, and past uses,11 as appropriate.

Meanwhile, the methodological objection to the analysis of ‘wholes’ (however construed) seems to us merely another mask for the gratuitous suspicion of big pictures and large meanings.12 Let us make our point more forcibly: all meaning is part of large meaning; and specific realizations cannot be understood at all without some conception of an overall reality to which they are seen to belong. Without the sense of a whole, it is impossible to discriminate between (or propose a restatement of) the peripheral and the central or, more simply, to grasp what has mattered when and why. In any case, the extraordinary phenomenon that classical antiquity has remained a source and a – shifting – point of reference down the centuries cries out for critical reflection in its own right, above and beyond specific engagements. And the consideration that any attempt to map the overall territory must be provisional (including any attempt to decide where ‘the’ territory stops) is no reason for not making the attempt. Quite the contrary: all critical or historical placing must be provisional; it is only by provisional attempts that more satisfying attempts are made possible in the future; and every interpreter of any instance or aspect of the classical tradition relies on some provisional placing in any case (their own or someone else's), whether they acknowledge it or not.

Our aim, in Part I of this book, is to get the overall shape of the tradition into view. To do so, we make free use of particular moments and examples, often pregnant moments and examples, whatever the possible methodological pitfalls involved in identifying a (or especially ‘the’) representative instance. In §3 (‘Eras’) we survey the place and status of classical antiquity within alternative historical frames, with special attention to the ways in which the classics have helped to determine how we conceptualize history and situate ourselves in time. The following section, on classics and education (§4), considers the professional experts, the sites of teaching and learning, the premises, and the techniques that have helped to sustain the tradition over the centuries. In §§5–10, from ‘authorities’ to ‘special relationships’, we explore shifts in taste and canonicity: which texts, which figures, which aspects of antiquity, have become influential or normative, and when, and why? Three sections are devoted to the distinctive trajectories, and problematics, of the visual arts (§11), popular culture (§12), and the Western languages (§13). We then consider the different modes of engagement with ‘the classical’ that ‘tradition’ has embodied, both in conspectus (§14) and with separate attention to three main ‘modes’: translation (§15), ‘scientific’ (and alternative) responses to the ancient world (§16), and looking at the past (§17). Finally (§18), we stand back and consider the place and scope of the classical tradition within Western culture as a whole: what belongs to it and, in particular, what does not belong to it?

Part I, it will be apparent, is not just ‘background’ for the more specific or circumscribed discussions that follow (though we are reasonably confident that it meets that need, among others). It represents an attempt to provide a coherent and theoretically informed refiguration of the classical tradition in its remarkable complexity: its categories and trajectories, definitions and problematics, contexts and relationships (suspected or unsuspected) – and also, not least, the correlations that emerge in some quarters and the seeming absence of correlations in others. Our quest for ‘meaning’ and our belief in the classical tradition ‘as a whole’ have not blinded us to the way that, for instance, individual creativities can sometimes defy general tendencies or, again, the way that one medium can work differently from others. Meanings do not have to be tidy, nor wholes the kind that number theorists work with.

Notes

1 The combination of legendary past and living memory typically gives the temporal profile of such traditions an ‘hour-glass shape’.

2 Compare the case studies in Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983).

3 We allude again to Eliot's ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’; cf. our Epilogue.

4 The underlying principle here we owe to Gadamer's Truth and Method (Wahrheit und Methode, 1960); we qualify it with reference to the inalienable freedom of human development. Nothing will come of nothing – but no formula for such development can be adequate that speaks the language of determinism and loses sight of individual agency and creativity (‘a growing and a becoming’, in Matthew Arnold's phrase).

5 Cf. §§26, 34.

6 As already in the Renaissance: ‘a first attempt … by going to the sources themselves to establish a past over which tradition would have no hold’: Hannah Arendt, ‘Tradition and the Modern Age’ (1968: cf. §34).

7 See, respectively, §§10, 33, 29.

8 Cf. Goldhill (2002) 297 and esp. Baehr and O'Brien (1994) 86–7: ‘“reception” implies a relatively weak or passive mode of acceptance or recognition.’

9 Not only, then, does the term, ‘classical tradition’, have a history (cf. §1 n.1); it also raises cross-cultural questions. Why do English, Italian (tradizione classica), French (tradition classique), have the term, if some other European languages do not?

10 But not unique: see esp. §12 on popular culture and §§19–22 on archetypes.

11 See Hall (2008a) for a related argument about ‘the classical’.

12 See Prologue, above.

§3

Eras

Periodization is inevitable and necessary, but in practice a tricky business, now that we have lost the robust naiveté of earlier ages. Today we think we know that any attempt to organize history and time is contingent on the observer – whether our point of reference is Hesiod and his five ‘Ages’, or the progression from mythos to logos in the tradition of Vico and Voltaire, or those late twentieth-century thinkers who have made it their business to deconstruct grand historical narratives. There are always possible reasons for huffing and puffing about chronological caesuras, most obviously because change needs to be calibrated against continuity. Not all the different groups in any one society (let alone all the individuals) march in step; ‘eras’ in literature, or art, or thought, do not necessarily coincide with each other or with ‘eras’ in political history; and (of direct relevance to the classical tradition) parallel developments in different countries, cultures, languages, do not always take place at the same time. Then again, hindsight tends to superimpose coherence that may well differ from perceptions at the time: modern understandings of the Renaissance as a definitive historical period centred on a broad-based artistic ‘rebirth’ of antiquity owe more to the classic study by Jacob Burckhardt than to any consensus during the Renaissance itself,1 while those living in the centuries before the Renaissance did not know that one day they would become ‘medieval’. Distinguishing ‘eras’ within the classical tradition is no easier than elsewhere. The ways that Greco-Roman antiquity has figured in post-classical culture have changed radically over time, but where best to draw the lines often remains an open question.2

For all that, distinguishing between conventionally acknowledged epochs has a great deal more to be said for it than against, both on a heuristic and a pragmatic level, quite apart from keeping the huffers and puffers in business. Accordingly, within the sequence that leads from Greco-Roman antiquity to our postmodern (or post-postmodern) present, we continue to distinguish late antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance (or ‘early modern’ period)3 – and then a series of periods which, indeed, oscillate awkwardly between the political and the literary-historical, art-historical, or history of ideas: the neoclassical era (subsuming the eighteenth-century Enlightenment); the Romantic period; the period of nationalism, empire, and ideology which in Britain, and sometimes elsewhere, is labelled the Victorian age; and then what one might call ‘classical’ modernity (subsuming the modernist movements, in art and literature) in, roughly, the first half of the twentieth century.

Revealingly, some of these ‘period’ labels derive from significant shifts in how one or other age assessed (or is perceived to have assessed) the inherent value, the historical position, and the larger cultural significance, of antiquity and the classical. Thus Petrarch ‘invented’ the Middle Ages as intervening between antiquity and a new age to come (§29), while Burckhardt defined the (Italian) Renaissance as an alliance between two separate cultural epochs of a single people.4 The classical, then, has played an essential part in providing Western cultural history with its ‘characteristic and unique “rhythmical form”’,5 and the more so because patterns of thought from antiquity itself have left their imprint on later constructions.

A case in point is the tendency to subdivide cultural traditions, whole cultures, and periods within cultures into ‘early’, ‘middle’, ‘late’, with latent but unmistakable implications of ‘immature’, ‘mature’, ‘in decline’. The schema can be traced at least as far back as Aristotle's view of Attic tragedy and Pliny's history of painting6 – and (in the same spirit) forward to the pioneering art criticism of Giorgio Vasari in the mid-sixteenth century and his sense of Roman art (on the model of the human life cycle) ascending from a ‘small beginning’ to a ‘great height’, before declining into ‘great ruin’;7 to the larger vision of ancient art developed by Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the eighteenth century; to the youthful Nietzsche's construction of Greek culture in the nineteenth; to Eliot's understanding of Virgil and ‘maturity’ in the twentieth.8 Related notions have been applied more widely – for instance, in Oswald Spengler's claim that ‘all civilizations pass through ages analogous to spring, summer, autumn, and winter; which is to say that historical organisms are equated with natural ones’.9 Less explicitly, notions of this kind underlie countless particular readings of particular periods in particular cultures, including those of concern to us. The particular readings, of course, may be disputed. For Petrarch, the Middle Ages were in effect ancient Rome's ‘winter’; to many Romantics, they were modernity's ‘spring’.

That medieval ‘winter’ (or ‘spring’) is, on any reckoning, a period with a special significance for the classical tradition, and is itself, from the first, marked by attempts to identify its own ‘historical’ relationship to the classical world. If the classical tradition begins where antiquity ends, we can pinpoint its birthday as 4 September 476 – the day when the ‘Arian’ warlord Odoacer dethrones Auden's ‘catholic boy’, the Roman emperor Romulus Augustulus, an act conventionally taken to mark the final demise of the Western Roman empire.10 Within a couple of generations, authors begin to refer to antiquity (‘antiquitas’) as a thing of the past; in the sixth century, for instance, Cassiodorus distinguishes it from ‘our own times’ (‘nostra tempora’) and ‘the modern period’ (‘saecula moderna’).11 However, such ruptures in high politics and historical consciousness should not be allowed to mask cultural continuities or, indeed, earlier moments that proved decisive in shaping antiquity's afterlife, including the formation of canons and the formative selection of artworks, texts, and ideas.

The first such moment is the conscious attempt to establish a corpus of approved texts through selective canonization which takes place hundreds of years earlier in third-century BC Alexandria: when the scholar-poets of that city (Callimachus and others) first set out to assemble and classify the approved literature of the Greek city-states in the creative centre of the new world-empire founded by Alexander, and seek, by selective and contrastive imitation of those works, to recuperate that earlier tradition as something exemplary for their own creative endeavour and (therefore) dissociated from it. And no less special is the moment, in that same century, when Livius Andronicus first translates a Greek text into Latin, thus initiating the momentous process of creating one national literature on the basis of another – an act of paradigmatic importance for the way later ages will come to deal with the classical canon and one which also guarantees the distinctively multilingual character of the classical tradition as a whole.12

During the late Roman republic and the early principate – say, between Cicero and Ovid – the Latin language reaches its ‘classical’ form, which has remained a point of reference and a standard ever since;13 and the interests of subsequent imperial elites ensure its perpetuation through the study of canonical authors (§4). Likewise, a parallel, but more diffuse, set of developments in the Greek-speaking ‘East’, from the Alexandrian recuperations to the linguistic Atticism of the first centuries AD, eventually establishes the Attic Greek of Aristophanes, Plato, and Demosthenes as what will eventually be called ‘classical’ Greek,14 in contradistinction both to the multifarious dialects of the city states before Alexander and to the Attic-based ‘common language’, the Hellenistic koine, which had been generalized as the lingua franca of the Greek world after Alexander and which continued to maintain its existence as the direct ancestor of the Modern Greek language today.15 The notion of the ‘classical’ and ‘the classics’ predates the advent of the classical tradition. And so too do the momentous tussles with an increasingly dominant Christianity that now define the tradition in the West for a millennium, and more.

Even though Christian writers look to the Bible for their basic temporal schemata, above all for the eschatological and chiliastic time-line from the creation of the world to the second coming of Christ,16 they increasingly turn history into a ‘privileged terrain of intellectual combat’ with pagan authorities.17 The integration of classical material into their organization of history constitutes an impressive piece of cultural imperialism.18 In the fourth century, Constantine the Great offers a messianic rereading of Virgil's fourth Eclogue,19 while Prudentius' hymn to the martyr Saint Lawrence rewrites the teleology of Virgil's Aeneid (where history effectively ends in the reign of Augustus) to proclaim Rome's overcoming of paganism as the ultimate historical achievement.20 Then, in the early fifth, Orosius makes much of the coincidence that Christ was born in the golden age of Augustus, thereby dissolving ‘the antithesis between Christianity and the Roman empire into the transhistorical continuity of all time since Christ's birth’21 – and this, despite the recent convulsive shock to the empire, when the Christian Visigoths sacked Rome in 410: an event that would inspire Augustine to compose his City of God, separating the historical from the spiritual realm, the real from the ideal.22