Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

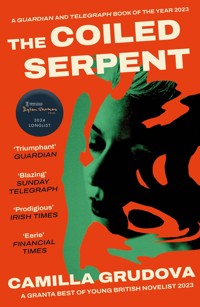

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

LONGLISTED FOR THE DYLAN THOMAS PRIZE 2024 GUARDIAN BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 TELEGRAPH BOOK OF THE YEAR 2023 A little girl throws up Gloria-Jean's teeth after an explosion at the custard factory; Pax, Alexander, and Angelo are hypnotically enthralled by a book that promises them enlightenment if they keep their semen inside their bodies; Victoria is sent to a cursed hotel for ailing girls when her period mysteriously stops. In a damp, putrid spa, the exploitative drudgery of work sparks revolt; in a Margate museum, the new Director curates a venomous garden for public consumption. In Grudova's unforgettably surreal style, these stories expose the absurdities behind contemporary ideas of work, Britishness and art-making, to conjure a singular, startling strangeness that proves the deft skill of a writer at the top of her game.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Camilla Grudova:

The Doll’s AlphabetChildren of Paradise

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 byAtlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024.

Copyright © Camilla Grudova, 2023

The moral right of Camilla Grudova to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EBook ISBN: 9781838956370

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Through Ceilings and Walls

Ivor

Description and History of a British Swimming Pool / Banya Banya!

The Custard Factory

The Green Hat

A Novel (or Poem) About Fan, Aged 11 Years or The Zoo

Mr Elephant

Avalon

The Poison Garden

The Surrogates

Madame Flora’s

The Coiled Serpent

The Meat Eater

White Asparagus

The Apartment

Hoo Hoo

‘I shall rage on raw meat’

VLADIMIR MAYAKOVSKY

Through Ceilings and Walls

I travelled to the island – one of the largest and most isolated in the world – by boat, and arrived on a drizzly, humid morning. The island’s government, in liaison with my university and my own government, had organised accommodation for me in a city not far from the purported site of some important Roman remains. I took a train there from the seaport, where they had confiscated my old maps and guide to their country, saying they were of no use anyway. They had, however, let me keep my small green edition of Homer’s Odyssey in the original Ancient Greek. At the train station, I was able to buy tea in a grey paper cup, a small boiled potato wrapped in foil and a chocolate bar. There was no one else in the station except for an old woman wearing a lopsided wig, strands of her own white hair sticking out from underneath the brown curls. She was slowly eating a boiled egg with one hand and clutching a grey paper cup of tea with the other. The chocolate bar was pale and very sweet. It did not melt in my mouth, but stayed solid until I chewed it and swallowed it in waxy lumps.

My accommodation was in a terraced house built from the city’s famous grey stone. It had large windows, one of which was blocked out with stone in the same pattern as the panes in the other windows. Many of the houses on the street also had this, some with more blocked stone windows than others.

My host was an older woman wearing a green tweed jacket and skirt. Stapled to the lapel of her jacket was a dried white flower. She wore a matching green hat, with plastic green eggs on it, and brown leather shoes. Her legs were bare even though it was cold. Our countries both spoke English, but it was hard to understand her, as every word sounded like a yawn. I stared at her mouth as she spoke. It was like there was something else in it besides her tongue, teeth, gums and tonsils. I imagined a strange growth in each of her cheeks, swollen and sore. There was wet snot in one of her nostrils and she dabbed it with a patterned hanky.

In the hall of the guest house there were framed grey etchings of whale and fox hunting, and a large painting of the Prime Minister. He wore a purple suit and tiny thick round spectacles. He was bald. He wore a white poppy on his suit lapel. I had seen paintings of him at the port where I arrived, and in the train station too. He had been Prime Minister of the island since long before I was born.

My landlady took me up to my room, using a torch, as the lamps above us were dim. She did not give me a tour of the rest of the house. The bedroom was sparsely decorated: a desk, an empty shelf and, taped to one of the walls, a picture, ripped from a newspaper, of a royal wedding from long ago. The bride’s face and hands were blocked out with green crayon scribbles, which made it look like the prince was marrying an empty white dress. The bed frame was in a nook in the wall, and it was so tall there were steps leading up to it. The room had been fitted with two hotplates, an electric kettle, an antique-looking toaster, a radio, a small variety of pots and pans and tins which said ‘Sugar’, ‘Coffee’ and ‘Tea’ on them but, on closer inspection, were empty. It was clear the landlady intended me to cook in my room rather than in the kitchen. I asked about a fridge or freezer.

‘We don’t normally refrigerate eggs and such things,’ she said, then pointed to the windowsill. ‘But that will do for milk. It is quite cold here, even in summer.’

After she left me to unpack my things, I realised there was a chamber pot in the room. I did not know if it was for decoration or my use. She did not show me where the bathroom was, but I found one down the hall from my room that seemed little used. There was black mould on the walls, a clawfoot tub stained with rust, and a vase of dried roses beside the sink. The window was misted glass and there was a very ancient newspaper by the toilet. I did not know if it was meant for wiping or to read, but I took it to my room to read and made my way to find toilet paper at a nearby shop.

The window display of the only shop I found was wholly comprised of cuts of raw red meat, as if the meat were the tongue of the shop and the window was its mouth. Inside I found potatoes, Brussels sprouts, small apples, eggs, white bread, bottles of milk, a larger variety of meat, lollipops, boiled sweets, the same brand of chocolate I had purchased at the train station which didn’t melt in the mouth, and spices in jars with orange lids. There were shelves and shelves of sweets, called Milk Chews, which came in white wrappers with a cow on. There were many of the same toy, a stuffed green wingless dragon or dinosaur with a long tail, and dolls with straw-blonde hair holding small national flags. These too were wrapped in plastic.

I was a vegetarian, as most people were in my country, so I avoided the cuts of meat. I bought apples, potatoes, eggs and a jar of peppercorns, along with a packet of coffee powder and some of the Milk Chews, out of curiosity. I had read that the inhabitants of the island only traded with one South Asian country, which led to their reliance on turmeric, pepper, curry powder, tea and coffee. It was a country they had once pillaged and claimed to own, and I suppose they had a certain violent pride in eating the spices from there. The coffee did not smell of coffee and the eggs were rotten inside.

At the guest house, I grabbed a pan and went to the bathroom to get water. It looked like there was a green olive stuck in the drain of the sink. I poured water from the tap on it to push it down, but it only quivered. I touched it – it was softer than an olive – and pressed on it. It quickly disappeared into the dark of the pipes.

When I returned I noticed a large porcelain jug in the room, filled with water. I suppose my landlady had filled it for me to prevent me from wandering to other parts of her house. I boiled the potatoes and ate them for supper with pepper. I found a copy of Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher in the room, and read it after my meal. I had given up on the newspaper I had found in the bathroom, as it only contained old royal gossip, recipes and children’s stories. There was no news of the outside world. I hadn’t seen any newspapers in the shops. I had an apple and some Milk Chews for dessert. The Milk Chews were beige squares that were hard to chew; I couldn’t finish one, and I took it out of my mouth, leaving it on my bedside table with the apple core. I brushed my teeth using the water from the bathtub drain.

The next morning, I set out to find ruins. I was met at my lodgings by an old man who said he was an eminent historian. He wore a green jumper with brown stains on it, a grey blazer and a sagging leather satchel, which smelled. His face was covered in cuts and long hairs that had been missed by the razor; he had shaved it that morning, I suppose, in expectation of our meeting. He was accompanied by a young woman whose black hair was braided into a crown around her head. She dressed like my landlady, more or less, and was not introduced to me, though it was she who drove the eminent historian and me to the ancient site. Her car was a white Volkswagen Beetle, with thick wool blankets over the seats, which I found stifling in the humid morning.

They took me to the site of an ancient wall which divided the north and south of the country. I felt I couldn’t dig around comfortably in front of them, so I waited until they were turned in another direction, chatting with the same overcrowded mouths as the landlady, then I crouched, my back turned to them, digging quickly with my hands. All I found was more dirt. I put some in my pocket, along with a stone. When I turned around, I saw the professor step on a large snail. He crushed it with his foot until it looked like a shattered teacup full of jelly. The woman giggled. It was a Roman snail, imported by the Romans, along with dormice, because they had liked to eat them.

When I returned to my lodgings, my landlady, waiting by the door, commented that my clothes were quite masculine, as was my short black hair. I said it was common in my country for both men and women to dress the way I did, and she said, ‘Not here.’

Back in my bedroom, I took the soil and stone out of my pocket and wrapped them in cling film. I would take the bundle back to my country and do tests on it in my university’s laboratory.

I woke up to find a long, floral dress on a hanger on my door, which had been opened an inch to hang it. I folded it – it smelled as if it had been worn long ago and not washed – and left it on a small chair in the hall.

The historian and his driver picked me up again, and took me on a city tour of bland government buildings, schools and nineteenth-century monuments of royals. I asked the historian about certain other sites I was intent on visiting – a bathhouse, a mosaic depicting fish and fruit, the remains of an amphitheatre – and how to get to them from where I was. He drew me a very vague map using his knee as a desk. When he handed it to me, I noticed the ink had leaked onto his trousers. I asked him about trains, and he shrugged and said he was driven everywhere.

I returned to my room, exhausted and disappointed, and examined the map the professor had given me. I decided I would leave in the morning, to take whatever train I could, wherever I could, to find more ancient sites. It was better than staying where I was. I put on my pyjamas.

I didn’t want to eat. I developed a stomach ache and wind – from eating too many of the apples, I supposed – and my faeces that night reminded me of the green gelatinous substance I had seen in the drain, which filled me with the horrible thought that it had been faeces in the sink. Worried about my health, and too bewildered to seek medical attention, I pushed my excretion around the toilet bowl with a spoon from my room, which I vowed to remember by the tiny royal on its tip and return to the kitchen. I don’t know what I sought: perhaps blood, or remnants of what I had eaten, but I was surprised when one of the pieces moved of its own accord and slid down the pipe. The others, less firm, crumbled as I touched them with the spoon, until they resembled pond algae.

There was another sound in the bathroom, coming from one of the plastic mousetraps that were all over the house, the kind like a miniature hallway with a door that locks once the mouse goes in. There were four in my bedroom alone. I had seen my landlady carrying three from elsewhere in the house to a bathroom. I had heard the toilet flush and she returned with the empty cages, their doors open, revealing speckles of mouse poo. The water pressure in the house was very bad; I couldn’t imagine the mice being swallowed with one flush, and instead imagined them squeaking as they drowned in shallow water with no escape.

I went downstairs to get more water, holding my stomach, and the now filthy spoon.

My landlady was playing Madame Butterfly downstairs. It sounded off – something was wrong with the shrill voice of the singer – until I realised she was singing in English rather than Italian.

My landlady wasn’t in the kitchen, but there was a gramophone in there I hadn’t noticed before. I walked towards it to see the record label, which read ‘Moira McKeller Sings Mrs Butterfly’. Around it were piles of commemorative royal plates from many, many years. All the crockery was in commemoration of different royal events: coronations, weddings, jubilees, their odd and ugly royal faces surrounded by leaves or gold braid.

I opened one of the drawers. Each piece of cutlery had a little royal face on the end. I put the filthy one in with the others.

On the table, there was roast chicken, herring and pigs’ feet, left over in bowls covered with cloth. I peeled back the cloth, watched the skins gathering condensation. The walls were covered in shelves of jars of spices, and jars of jams and chutneys, a few bottles of what looked like homemade ketchup, dark brown and thick. There was some food left on a plate, with a fork and knife set down as if it were a meal to be returned to: grey slices of chicken slathered with strawberry jam.

I turned on the kitchen tap. Water didn’t come out: something slimy and green did. Something was wrong with the plumbing, and my faeces was coming out of the kitchen sink. It did not stop coming out, there was so much – it was more than I alone could have produced, accompanied by hair and tiny bits of undigested food. I would have to leave the taps to run, until the slime cleared.

I thought I saw something move inside the gramophone’s flaring horn, the same quivering green exuding I had seen in the sink, and backed away. There was a white and pale yellow growth on the pile of green coils in the sink, like the yolk of a partially cooked egg. There was no sign of water. I would break it open with a fork or knife. I took the fork off the plate of chicken, and as I moved closer, the smell became worse, the smell of old pipes, of everything swallowed by a drain. The growth moved, the top layer disappearing, revealing a dark gap of pupil. I could make no sense of its anatomy. Its body was everywhere, not just in the sink. It was in the pipes, the walls, the furniture. I was already in its stomach.

Ivor

‘The days passed.’

ALFRED HITCHCOCK, DOWNHILL, 1927

We are all second, third or even fifth sons. We were sent to Wakeley Boarding School aged eight for Year Five and stayed on until Year Twenty. We didn’t count how many years that was, or fully comprehend how much time constituted a year; we were just excited to go off to boarding school like our fathers and older brothers, to leave the nursery. We were disappointed not to go to the same school as our fathers and eldest brothers, but so were our sisters, who were not sent to school at all. We were given a brochure from Wakeley: there was an illustration of a beautiful, dark-haired boy playing rugby on the cover. Our nannies packed up our teddies and toys, photos of our families, shortbread and chocolate. Some of our nannies wept; we did not know why: we assumed we would see them again soon.

Wakeley was in the middle of the countryside. Which county, we couldn’t say. Some of us remembered our fathers saying they were taking us to Derbyshire, others to Somerset, though a senior student with a passion for nature said based on the studies he did of animals and flora on the school grounds we were in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. The land surrounding the school was beautiful and hilly; the grounds so extensive we had no need to go beyond them. There was a stable with horses, a swimming pool, tennis courts, a library, a graveyard, a chapel and several dormitories, each with its own housemaster and tutors. We had advanced lessons: every year for biology, a zoo donated an elephant fetus for us to dissect and for months the specimens lay in tanks and jars of formaldehyde in our classroom like wrinkled old raincoats. There was a big grey computer that could do sums. Languages we could study ranged from Arabic to Russian.

As younger boys, we had to do tuck-shop runs for the seniors in our house who had their own rooms, a mark of their status. Chocolate bars, haemorrhoid cream, newspapers, boiled sweets, Gentleman’s Relish, malted milk, cigarettes. One senior would cane us if his newspaper was wet. We didn’t like the seniors and didn’t understand how they could look like our fathers and grandfathers yet were still boys at school wearing the same striped ties and caps as us. The headmaster told us they were special boys who had a lot to learn before going out into the world, and that boys who entered the world too soon missed school and their friends terribly. We half forgot about these older students unless we were doing chores for them. We had our own classes, games, celebrations, clubs – the Cheese Club, the Ancient Rome Club, the French Club. The older boys blended into the antique furniture of our houses, red-faced and dusty like velvet armchairs, or spindly and brown like side tables.

As we got older and became seniors ourselves, we were dependent on those tuck-shop excursions, those moments of forced tenderness from the younger boys. We recognised the disappointment of a damp newspaper, pages stuck together, that as new, young boys we had not understood.

The main chore we had to do for the seniors was make toast and cut it into little pieces for them. We saw house tutors tie bibs around their necks for each meal and accompany them to the bathroom or push their wheelchairs throughout the halls of Wakeley, cut their toenails in the evening and insert their false teeth in the morning. Our teachers told us it was gracious to help the elderly. We had to ignore the sounds of them soiling themselves in the halls, or when they pinched our bottoms, weeping as they did so, their own backsides sagging like abandoned bowls of porridge.

The boys in the fourteenth form who resembled our teachers and our half-forgotten fathers were still hearty and athletic. They didn’t need our help and they ignored us completely. They had their own clubrooms where they drank and argued. Occasionally one would come into our dorms at night very drunk and the tutors had to chase them off using brooms and smiles. Sometimes they were so quiet that none of us, not even the tutors, heard them, and we would wake up in seething, mysterious pain to find one of them sleeping beside us, hulking and stinking.

Everyone competed to prepare toast for Ivor, a head boy and senior. He didn’t look like any of the other seniors: he was still beautiful, he was still captain of the rugby team, played lacrosse, swam, sang and took part in all sorts of games.

He never asked for anything from the tuck shop but we brought him presents anyway. We learned that he liked rhubarb and custard sweets and disliked the newspapers – he never read them and rolled the pages into balls he threw at other boys, sometimes filled with flour so that those he hit were left with white faces like clowns.

Ivor was the only one we served toast whole to – he didn’t need it quartered.

For breakfast, Ivor had toast with anchovy paste, a beef sausage split down the middle and filled with marmalade and a cup of tea with neither milk nor sugar.

He ate heartily of whatever was on offer for lunch and supper: steak pie with stew, boiled fish, roasts, kedgeree, Wellington, rarebit, ham, puddings, and in later years, lasagne and curry, chips, baked potatoes and chilli.

Ivor had dark curly hair that never went grey, red lips, flushed cheeks and a pallor so powdery some of us thought he wore makeup.

The so-called ‘makeup’ did not come off or run in the shower or bath, nor did he sweat when he played sports.

When he was playing a rugby game, a few of us snuck into his room and ransacked it, looking for makeup or hair dye, but we didn’t find any. In the drawers of his desk and under his mattress we found only old playing cards and a purple wrapper from a chocolate bar.

On his desk was an unopened Kendal mint cake, three Rupert annuals and his Greek books, a cup full of pens, a tin of rusty pen nibs and a jar of blue ink, a paper bag of stale penny sweets shaped like bottles and babies. He only wrote with dark blue ink and we imitated him. Most of the teachers could not tell the difference between dark blue and black, but we could.

Above his desk he had a picture of the Queen. When the Queen died, the image was replaced by a picture of the King, then later another king, and then a queen again. No one knew where the old pictures ended up. They were always in the same frame.

He had piles of sports things: a pig’s bladder football, wooden tennis rackets and lacrosse sticks made with sheep intestine webbing, yellowing cricket pads. On his bed was a dirty teddy bear with a crooked face named Bombozine. In between Bombozine’s legs were badly sewn stitches holding a hole together. There were milk stains on the legs, the fur stiff and bunched together.

He had a small taxidermy crocodile, mounted on his wall, and a wooden African mask. These items were a source of wonder to us.

When we first arrived at Wakeley we copied the way Ivor did everything until his habits came naturally to us. His way of pushing back his hair when reading, or humming as he tied his shoes, the way he wrapped his wool scarf around his neck and used words like ‘ripping’ and ‘first rate’ and the Scots word ‘blether’. We soon called him Ivy. Some of us bought red lipstick from the tuck shop and wore it as we got older and our natural boyish colours faded.

The toilets at Wakeley were unreliable, with cracked wooden seats, and rarely flushed properly. We would often judge each other’s defecations by size and shape. Once, a boy using the bathroom after Ivor discovered a perfectly white piece of faeces, like crushed wet chalk. It smelled of nothing. He said it reminded him of a cloud. Like most of us, Ivor did not like to take baths or showers because the water was lukewarm. Our hair was greasy, our bottoms as dirty and cracked as those of stray cats. We rolled in mud on the grounds and spilled mashed potato, snot and puddings on our uniforms.

Every term a man would come to inspect everyone’s hair for lice. He had a black comb which he kept in a jar of blue liquid and carefully brushed each boy’s head, wearing a pair of magnifying spectacles. He was very tall and thin with a pot belly. His own head was shaven, except for a white wisp over one ear. He complained to the headmaster if he found too much dandruff, saying the boys needed to have their hair washed more often.

Though Ivor’s hair always appeared to be clean and well brushed, he had the most bugs in his hair. Each time the inspector came he would find fleas, bedbugs, ticks, little white worms, dozens of eggs, and Ivor would be prescribed a foul-smelling pink shampoo we never saw him use. The inspector seemed to enjoy combing through Ivor’s hair; almost every strand of hair was covered in black insects.

The man squeezed the bugs between his fingers then dropped them on the towel positioned beneath his inspecting stool where the boys sat. One boy, Clive, who was more infatuated with Ivor than most, grabbed one of the bugs that was still alive; he cradled it in his hands and took it to his room where he put it in an old cigar box he had stolen from a senior. Unoriginally, he named it Ivor.

Clive fed the bug bits of sweets and cake and drops of his own blood by pricking his finger with the tip of his fountain pen. It grew very fat and soon became the size of a guinea pig, and he got a bigger box to put it in. It gave off a sickly sweet smell from the food Clive gave it. It was round and brown in colour with bits of black, as shiny as the polished wooden floors in our dorms, the ridges in its shell resembling the cracks between the boards. It had six furry legs and a pair of pincers.

He had read in a magazine about flea circuses and tried to teach the creature tricks. He trained it to jump through a ring and climb a set of steps he made from toy blocks and rubbers.