18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This is the story of two single-handed non-stop round-the-world voyages: Robin Knox-Johnston's in 1968/69 and Ellen MacArthur's in 2004/05. Although there were similarities – both voyages started and finished in Falmouth, for instance, and neither sailor was in a conventional race – the story is mainly one of contrasts, mostly as a consequence of thirty-six years of technological developments. These gave MacArthur the opportunity for a considerably faster voyage, but that didn't necessarily make things any easier for her. When Knox-Johnston set sail in Suhaili, no one knew if it was possible for a human being or a boat to survive such a voyage; and when MacArthur commissioned her boat B&Q, many considered that a high-performance trimaran of that size could not be safely sailed around the world by one person. Whatever comparisons are made, the question as to which was the greater achievement is futile: both voyages were utterly remarkable. MacArthur is no longer 'the fastest', of course – her time has since been beaten by three Frenchmen – but she is still the fastest British solo circumnavigator, while Knox-Johnston's record as 'the first' will be there for all time.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

THE FIRST AND THE FASTEST

THE FIRST AND THE FASTEST

COMPARING ROBIN KNOX-JOHNSTON AND ELLEN MACARTHUR’S ROUND-THE-WORLD VOYAGES

NIGEL SHARP

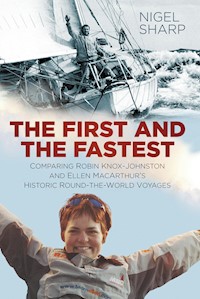

Front cover illustrations:

Top: 22 April 1969: Robin Knox-Johnston waving from his 32ft yacht Suhaili off Falmouth, England just before completing the world’s first solo non-stop circumnavigation, having set out from Falmouth 312 days earlier. Even seasoned yachtsmen thought it would be an impossible feat, and for everyone else it was: of the nine starters in this Sunday Times-sponsored round-the-world race, Robin was the only finisher. (Credit: Bill Rowntree/PPL);

Bottom: 9 February 2005: Ellen Macarthur in Falmouth, soon after breaking the solo non-stop round-the-world record. She crossed the finishing line – between Ushant on the North coast of France and the Lizard on the Southwest coast of England – the night before, having completed the voyage in 71 days 14 hours 18 minutes and 33 seconds, over a day quicker than the time set by French sailor Francis Joyon a year earlier. (Credit: Phil Russell/PPL)

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Nigel Sharp, 2018

The right of Nigel Sharp to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8694 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

1 Robin and Ellen

2 The Golden Globe – the Conception

3 Background to Ellen MacArthur’s Voyage

4 Communications – 1968 and 2004

5 Choice of boats

6 Falmouth

7 Departures

8 The Golden Globe

9 MacArthur’s Voyage

10 Homecomings

11 Tributes

12 Navigation

13 Weather and Forecasting

14 Repairs and Maintenance

15 Well-Being

16 What They Did Next

17 More Record-Breaking

18 The French Connection

19 Other Round-The-World Races

20 The 2018/19 Golden Globe

Bibliography

With huge gratitude to Robin Knox-Johnston and Ellen MacArthur, for their contributions to this book, but, much more than that, for their epic voyages.

Foreword

I was 20 years old when Robin Knox-Johnston sailed into the record books. His solo non-stop circumnavigation remains the most significant small boat voyage from the past century and, as with thousands of others, had a major impact on my life.

A college student, I was captured by the whole adventure and avidly read every report on the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race. It was as much a race between Fleet Street’s finest as it was on the water, with the Sunday Mirror (which sponsored Robin), Sunday Express and News Chronicle all vying to scoop The Sunday Times on their own story.

And there wasn’t much news to go round. Knox-Johnston’s radio was swamped by a wave early on in the Southern Ocean, and Frenchman Bernard Moitessier didn’t even have one, relying instead on a catapult to fire nuggets of information to passing ships. But that didn’t stop the Sunday papers from running double-page spreads each week and sending their correspondents on expensive wild goose chases in an effort to intercept these boats. In the weeks, even months, between valid reports and sightings, these correspondents simply interviewed their typewriters, pinpointed positions with the accuracy of a 6-pint darts player and swallowed whole the fraudulent position reports and speed record claims from Donald Crowhurst, who, instead of chasing the leaders round the globe, skulked around in the South Atlantic ready to ‘slot back in’ once the leaders had turned north after rounding Cape Horn.

These newspaper hacks were predicting that it would be a neck-and-neck finish from as far away as New Zealand, the last contact Knox-Johnston and Moitessier had with the outside world, and continued with this paper-selling pretence until the Frenchman fooled all the ‘experts’ by turning up in Table Bay, Cape Town and Suhaili was finally sighted by the oil tanker Mobil Acme two weeks before his finish.

In reality, Moitessier rounded Cape Horn nineteen days behind Knox-Johnston with neither knowing where the other was. Robin is a firm believer that the Joshua skipper, who had set out from Plymouth six weeks after Suhaili left Falmouth, knew in his heart that the race was ‘lost’ even before crossing the Date Line, and simply continued East after rounding Cape Horn to ‘Save his soul’ as Moitessier put it, because he was by then at one with the sea and didn’t cherish the idea of returning to an increasingly commercial world.

The myth, still widely believed in France, is that Moitessier led Knox-Johnston around Cape Horn and would have won the race easily had he not been thinking on a higher plane.

But as readers, we lapped up whatever story would sell newspapers and thirsted for more. Knox-Johnston’s triumphant return to Falmouth was the first live outside broadcast streamed by the BBC, the Sunday Mirror was the first to experiment with ‘wiring’ a photograph over the airwaves from out at sea, (to scoop The Sunday Times again), and thousands lined the waterfront to get a first sight of this new national hero.

Knox-Johnston’s achievement was as significant then as Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon three months later. The voyage encouraged hundreds of thousands around the globe to jump in a boat and led me to take up sailing as a career. People with the fortitude, strength of character and sheer bloody determination to achieve such heights in life usually emerge just once a decade. Britain was lucky to have three emerge in one era: Francis Chichester, Alec Rose, Knox-Johnston – and Chay Blyth who, after dropping out of the Sunday Times race, returned to become the first to complete a solo non-stop circumnavigation the other way round.

It took another three decades before Britain could champion another superhero in the diminutive form of Ellen MacArthur, a 5ft 2in (1.57m) human dynamo. The challenge for her was very different to that faced by Knox-Johnston. Her 75ft (23m) trimaran was built for speed and equipped with every labour-saving device, and far from being alone with her thoughts for months at a time, as Robin had been, she had weather routers, mast, sail and boat technicians, and most of all a manager/mentor on call via satellite phone twenty-four hours a day.

This of course is the modern way, but her feat still required great fortitude and spirit. And by smashing the record by a day and a third, her achievement also had a major impact on reducing male chauvinism within the sport and led to a lot more young women taking part.

Barry Pickthall Media Director, 2018 Golden Globe Race and Chairman of the Yachting Journalists’ Association.

Knox-Johnston’s route

MacArthur’s route

Introduction

Falmouth, Cornwall, is a town steeped in maritime history, but rarely can it have witnessed two more significant events than the arrival of two particular sailing boats: one in April 1969 and the other in February 2005. Although they were fundamentally different types of boats – one a 32ft 6in (9.9m) ketch with a ‘wallowing trawler appearance’ as she was later described in The Sunday Times, and the other a 75ft (22.9m) lightweight trimaran – they were inextricably linked by a common accomplishment: they had both been sailed from the same port single-handed and non-stop around the world and, in doing so, had reached hugely significant milestones in maritime history. The first was Suhaili, whose skipper Robin Knox-Johnston had left Falmouth 312 days earlier and had become the world’s first non-stop solo circumnavigator; the second was Ellen MacArthur’s B&Q which, in a little over seventy-one and a half days, had become the fastest.

Prior to Knox-Johnston’s voyage, about thirty people had sailed single-handed around the world, but they had all stopped along the way, the majority of them numerous times. Of these, there were three particularly notable circumnavigators.

The very first was Joshua Slocum, who left Boston, USA in April 1895 in his 36ft 9in (11.2m) sloop Spray. His initial plan was to sail eastabout, but when he stopped in Gibraltar – with a view to then continuing through the Mediterranean Sea and the Suez Canal – he was advised by officers of Britain’s Royal Navy who were stationed there that it would be dangerous to continue that way due to the threat of pirates. So he changed his mind and went westabout, and from Gibraltar he sailed across to South America, through the Straits of Magellan and eventually around the Cape of Good Hope and back to America. He arrived in Newport, Rhode Island – having converted Spray into a yawl by adding a mizzen mast along the way – in June 1898, having sailed 46,000 miles.

Vito Dumas was an Argentinian who, in June 1942, set off from Buenos Aires in his 32ft (9.76m) Colin Archer ketch Lehg II while most of the world was waging war. Four hundred and thirty-seven days later, he returned to the same port, having sailed around the world through the Southern Ocean, stopping just three times: in Cape Town, Wellington in New Zealand and Valparaiso, Chile. He was the first solo sailor to round Cape Horn.

Francis Chichester was a British adventurer who originally achieved fame though his solo flying exploits. In 1929 he flew a de Havilland Gipsy Moth biplane from England to Australia, taking forty-two days. Two years later he became the first person to fly solo from New Zealand to Australia, using the same aircraft but now fitted with floats so he could land and refuel at Norfolk Island and Lord Howe Island.

After the Second World War, he became interested in sailing, and in 1953 he bought a yacht called Florence Edith and changed her name to Gipsy Moth II. He raced her with increasing enthusiasm, and in 1959 he commissioned Robert Clark to design, and John Tyrrell of Arklow to build, a 40ft (12.2m) cutter, which he named Gipsy Moth III. The following year he was one of five competitors to compete in the very first single-handed transatlantic race, sponsored by the Observer newspaper and therefore known as the Observer Single-handed Transatlantic Race (or OSTAR). Gipsy Moth III won the race in a time of just over forty days, beating Blondie Haslar – who had done much to develop self-steering systems, which were fundamental to single-handed ocean racing – by eight days. Four years later, the OSTAR attracted fifteen competitors, but this time, although he improved his time by over ten days, Chichester’s Gipsy Moth III was beaten into second place by the Frenchman Eric Tabarly in his custom-built 44ft (13.4m) ketch Pen Duick II. As a result of this, Tabarly was ‘feted in his homeland,’ Yachting World reported, ‘and after a tumultuous welcome in Paris, General de Gaulle made him a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.’

Soon after completing the 1964 OSTAR, Chichester commissioned Illingworth and Primrose to design, and Camper and Nicholsons to build, a boat specifically for him to sail solo around the world, stopping just once. The result was the 53ft (16.1m) ketch Gipsy Moth IV, which Chichester famously came to despise, although it is generally considered that her flaws were the result of the unreasonable demands he made on her designers. On initial sea trials in the Solent, she heeled over alarmingly in a Force 6 gust. ‘Here was a boat which would lay over on her beam ends in the flat surface of the Solent,’ Chichester wrote, ‘the thought of what she would do in the huge Southern Ocean put ice into my blood.’ Gipsy Moth was then slipped so that 2,400lb (1,090kgs) of additional ballast could be added, but even then he described her as ‘still horribly tender’. Once the voyage was under way he found more faults: she had a tendency to ‘hobby horse’ when sailing close hauled, whereby relatively small waves would reduce her speed significantly and, if she had four or five such waves in succession, she might even come to a standstill; he had trouble setting up the self-steering gear so that she would keep on course when close hauled; and finally she had a tendency to broach – ‘as easily as a flick of the cane’ – when sailing downwind in a big sea. He wrote after his circumnavigation:

Now that I have finished I don’t know what will become of Gipsy Moth IV. I only own the stern while my cousin owns two thirds. My part, I would sell any day. It would be better if about a third were sawn off. The boat was too big for me. Gipsy Moth IV has no sentimental value for me at all. She is cantankerous and difficult and needs a crew of three – a man to navigate, an elephant to move the tiller and a 3ft 6in chimpanzee with arms 8ft long to get about below and work some of the gear.

Nonetheless, she safely carried him around the world as he had planned. By the time he arrived back in Plymouth he was a national hero, and he was welcomed by a vast armada of small boats and a quarter of a million people on Plymouth Hoe. Soon afterwards he was knighted at Greenwich by Queen Elizabeth II with the same sword that her namesake had used to knight Francis Drake.

Chichester’s declared target was to complete each of the two legs of his voyage – from Plymouth to Sydney and back again – in 100 days which, he estimated, was the average time it used to take the wool and grain clipper ships to sail the same route in the nineteenth century. In that respect he failed – he took 107 and 119 days – but the voyage was nonetheless ground-breaking. It was the first ever solo circumnavigation with only one stop; each leg of his voyage was more than twice the distance that he, or any other single-handed sailor, had ever sailed before; and it was also the fastest ever circumnavigation by any small vessel. He had paved the way for someone to go one better: to sail single-handed non-stop around the world.

The thought that he might attempt this feat first occurred to Robin Knox-Johnston in March 1967, when he was at his parents’ home in Kent while on leave from his job as a merchant seaman. Chichester was still at sea and would not finish his voyage for a couple of months, and Knox-Johnston’s father was reading a newspaper article about Eric Tabarly, who was planning to compete in the 1968 OSTAR in a new trimaran. Father and son began to speculate what other plans Tabarly might have, and whether these might include a non-stop solo circumnavigation. ‘It’s about all there is left to do,’ said Knox-Johnston senior. This planted a seed of thought in his fiercely patriotic son’s mind: it had to be a ‘Brit’ who would achieve this landmark voyage first.

In 2003, the record for sailing single-handed non-stop round the world was a little over ninety-three days. This had been set in a 60ft (18.3m) monohull by the Frenchman Michel Desjoyeaux when he won the 2000/01 Vendée Globe, the fourth edition of the race that was first held in 1989/90, and which starts and finishes in Les Sables-d’Olonne on France’s west coast. Ellen MacArthur finished second in that race, just over a day behind Desjoyeaux, and two years later she made the decision to commission a trimaran with the express purpose of trying to break a number of records, including a circumnavigation. However, by the time her new boat was launched, her primary goal would be considerably more difficult: another Frenchman, Francis Joyon, had just completed the voyage in his own trimaran in a little less than seventy-three days. ‘On that day the challenge before us got a whole lot bigger,’ she later wrote.

Robin and Ellen

Robin Knox-Johnston

Robin Knox-Johnston was born in Putney, London on 17 March 1939, the eldest of four brothers. During the war, he and his family were bombed out of their flat near Liverpool and then moved to Heswall on the Dee Estuary, and it was there that his interest in boats took root. At the age of 4 he built a raft and carried it a mile to the sea, where it sank as soon as he stood on it. ‘I had lost my first command,’ he later wrote. His next craft – a 10ft (3.05m) canoe – came a decade later when he was a pupil at Berkhamsted School in Hertfordshire. He built her in his grandparents’ attic, but she too sank, or at least initially, but she was later declared seaworthy when the family took her to Sussex for their summer holidays.

At the age of 17, Knox-Johnston was keen to join the Royal Navy. He duly sat the Civil Service Commission’s exams, but didn’t make the grade in all of the subjects. He later wrote that, at that time, he ‘had difficulty in applying theory and experiments of the General Certificate syllabus to any practical problems that came my way.’ So he decided to apply for the Merchant Navy instead, and on 4 February 1957 he joined the British India Steam Navigation Company’s ship Chindwara as an Officer Cadet. He spent most of his apprenticeship on the Chindwara as she made her way backwards and forwards between London and various ports in East Africa, and in October 1960 he passed his Ministry of Transport Second Mate’s Certificate exams. He then served on British India’s Dwarka between Indian and Persian Gulf ports. In 1962 he married Sue, his childhood sweetheart, and they set up home in Bombay and subsequently had a daughter, Sara.

It was on his next ship, the Dumra, that he served with Peter Jordan, and the two of them decided to build a boat and sail it back to England with a view to selling it at a profit. The result was Suhaili, which was launched on 19 December 1964. Soon afterwards, Knox-Johnston returned to England to take his Master’s Certificate and also to take up a new role as a Royal Naval Reserve Officer.

By this time, Jordan (and also Mike Ledingham, who had joined them in the Suhaili project) had made other plans, so when Knox-Johnston was ready to sail her home from India, he recruited his brother Chris and a Marconi radio officer called Heinz Fingerhut as crew. They set sail on 18 December 1965 – almost a year to the day after Suhaili had been launched – and, after calling at Muscat, Salala, Mombasa, Zanzibar, Dar-es-Salaam, Mtwara, Beira and Lourenco Marques, they arrived in Durban in April 1966. By now they had all run out of money, so they decided to stay in Durban and seek employment. After eight months’ work – Knox-Johnston serving on merchant ships – and a further delay while they replaced Suhaili’s mainmast which had been broken in an accident, they set sail again. After calling at East London and Cape Town, they set off on the final non-stop leg back to England on 24 December. Seventy-seven days later, they arrived at Gravesend on the Thames.

Knox-Johnston then reported to British India that he was ready to resume his Merchant Navy career, but he was told that the ship on which he was due to serve as First Officer, the Kenya, wouldn’t arrive in London for another month and so his leave would be extended. It was during that month that he had that fundamentally life-changing conversation with his father.

Ellen MacArthur

Ellen MacArthur was born in Derbyshire on 8 July 1976. Her parents were both teachers, and she had two brothers. Just as Knox-Johnston built his first vessel when he was 4, MacArthur first dreamt of being at sea at the same age. She first sailed when she was 8, on her Aunt Thea’s 27ft (8.2m) boat Cabaret (a Diamond 27) at Burnham-on-Crouch, and it wasn’t long before the family took regular holidays on the south coast with sailing at the top of the agenda. MacArthur later wrote that, whenever Cabaret’s sails were hoisted, she ‘was riddled with a restless excitement’.

From then on, she began to save her dinner money – just keeping back 80p per day to buy beans and mash – and this allowed her to buy her first boat, a Blue Peter dinghy which she named Threpn’y Bit. She loved animals and had ambitions to be a vet but this plan reached a significant setback when she contracted glandular fever just before she was due to take her A-Levels. However, while she was laid up in bed she happened to watch a television programme about boats sailing around the world and this made a hugely significant impression on her. It was at that moment that she realised she would pursue a career in sailing.

She then began to teach sailing courses in Hull and she herself passed her Yachtmaster exams at the age of just 18, as a result of which she won the 1994 Young Sailor of the Year Award. When she was presented with this she had the opportunity of meeting her childhood hero Robin Knox-Johnston, with whom she found herself posing for photographs.

She then bought a Corribee 21 that she named Iduna and which, in 1995, she sailed around mainland Britain single-handed, anticlockwise via the Caledonian Canal. She set off from Hull on 1 June and in many of the thirty-nine ports she visited she made a point of meeting schoolchildren and local sailors at their yacht and sailing clubs Admittedly, she did ‘race’ for the last twenty-four hours to avoid arriving back in Hull on Friday 13 October: she got there the day before. In the process of the voyage she even managed to raise money for the RNLI. ‘Everything about the journey fascinated me,’ she wrote after she completed her voyage, ‘and every decision, repair or manoeuvre was part of a huge puzzle that I was relishing the opportunity to solve.’ Iduna was exhibited at the London Boat Show the following January and it was there that she met Mark Turner who was, at that time, the sales manager for the marine equipment company Spinlock.

During the course of 1996, MacArthur sailed offshore for the first time, crossing the Atlantic twice in Open 60s, two-handed both times. The first was a delivery trip from Boston, USA to France and then, almost as soon as they arrived, she flew to Canada so that she could race with Vittorio Malingri on his Open 60 Anicaflash in the Quebec to Saint-Malo race, a voyage on which they ran out of gas halfway, and of food two days before they finished.

In January 1997, she and Mark Turner formed a business partnership – which would soon become the company Offshore Challenges – while the two of them were planning to take part in the Mini Transat. This is a biennial single-handed race from Brest to Martinique via Tenerife, which is sailed in the 6.5 metre Mini class. MacArthur, sailing Financial Dynamics, was the only woman in the 51-boat fleet, and she finished twenty-sixth on the first leg and fifteenth overall, while Turner was fifth. After the race, Turner decided he would step back from competitive sailing so that he could manage both the company and MacArthur’s subsequent sailing programme.

The next milestone in MacArthur’s sailing career might have been the Around Alone – the four-yearly ‘stopping’ race around the world which was previously known as the BOC Challenge and would later be renamed the Velux 5-Oceans. The next edition was due to start in the latter part of 1998 from Charlestown, USA with stops in Cape Town, Auckland and Punta del Este before finishing back in Charlestown. MacArthur, however, was looking further forward, to the Vendée Globe, the non-stop round the world race, the next edition of which would start in Les Sables d’Olonne in November 2000. That was her real goal but she and Turner knew that she had to have the right preparation for it, and they decided that the Around Alone would detract from that. They thought she would be better off taking part in the French classic Route de Rhum – the four-yearly single-handed race from Saint-Malo to Guadeloupe – while watching the progress of the Around Alone competitors.

In June 1998 MacArthur took part in the two-handed Round Britain and Ireland Race with David Rowen in the Open 50 Jeantex and came first in class. She was then fortunate enough to come to a last-minute agreement to charter Pete Goss’s Open 50 Aqua Quorum – in which he had competed in the previous Vendée Globe – to take part in the Route de Rhum.

The boat was renamed Kingfisher after the company whose high-street brands included Woolworths, Comet, B&Q, Castorama and Superdrug, and from whom she and Turner had managed to secure sponsorship. In a fleet of seventeen monohulls – most of them Open 60s – she finished fifth and was the first of the Open 50s. In recognition of this achievement she became the youngest ever winner of the Yachtsman of the Year award, and soon afterwards Yachting World described her as ‘Britain’s most single-minded 22-year-old’.

During the course of 1999, as part of her ongoing plan to learn as much as possible about racing Open 60s, MacArthur sailed with Frenchman Yves Parlier on his Aquitaine Innovations, first in the fully-crewed Round Europe race, and then in the two-handed biennial Transat Jacques Vabre from Le Havre to Cartagena, Colombia. She also took part in the Fastnet Race with Laurent Bourgnon in his 60ft (18.3m) trimaran Primagaz, campaigned a Laser 4000 dinghy with Olympic sailor Paul Brotherton to sharpen her racing skills, and received personal tuition regarding weather routing from meteorological expert Jean-Yves Bernot.

The boat in which MacArthur would do the Vendée Globe was designed by Merf Owen and Rob Humphreys, and built by Marten Yachts in New Zealand – the first Open 60 to be produced in that country. She was officially launched by Sir Peter Blake’s wife Pippa – and christened Kingfisher – in Auckland on 18 February 2000, the eve of the America’s Cup which Team New Zealand would successfully defend. ‘Ellen climbed up to the first set of spreaders and popped open a bottle of champagne,’ it was later reported in Yachting World. ‘Firecrackers exploded and the boat and crowd were showered in streamers and confetti.’

At the time of the official launch, MacArthur had had a chance to sail her new Kingfisher just once. ‘She handled brilliantly,’ she said afterwards. But she soon got the opportunity to share a lot more sea miles with her. Part of the reason that a New Zealand company had been chosen as the builder was to give MacArthur experience of sailing in the Southern Ocean while bringing the boat back to Europe. For that stretch of the delivery she had a crew of three but after they got off the boat – in a cove called Caleta Martial, about 10 miles north of Cape Horn – she had the chance to sail her single-handed for the remaining 7,000 miles.

On 4 June 2000, just four months after Kingfisher was launched, MacArthur set off from Plymouth at the start of the Europe 1 New Man STAR single-handed race (the equivalent of Chichester’s OSTAR) to Newport, Rhode Island – the first time she had raced an Open 60 solo. In a fleet of nineteen IMOCA 60s, she became the first British winner of the race since 1968, a feat which Yachting World described as ‘a colossal confidence boost for Ellen MacArthur’.

Five months later she was in Les Sables d’Olonne as the youngest ever entrant in the Vendée Globe, the start of which was delayed by four days due to a ferocious storm in the Bay of Biscay. The Frenchman Michel Desjoyeaux took the lead soon after reaching the Southern Ocean, at which point MacArthur was in fourth place, but when she rounded Cape Horn she had moved up to second, about 600 miles behind Desjoyeaux. On the way up the Atlantic she gained on him and before long the two boats were trading places. They were neck-and-neck at the equator but MacArthur’s chances of winning were eventually scuppered when she hit a semi-submerged object – most likely a container – and had to slow down and make repairs. She eventually finished in second place, just a day behind Desjoyeaux but almost two days ahead of the third boat and over a week ahead of the fourth. She arrived back in Les Sables d’Olonne to a tumultuous welcome, which Andrew Bray, the editor of Yachting World, later described as ‘quite the most incredible sight I have ever seen at any sailing event the world over, and that’s in a career in sailing journalism of thirty years.’

MacArthur’s Corribee Iduna, in which she had sailed around Britain less than six years earlier, had been refitted and shipped to Les Sables and put on show there. MacArthur was also taken aback by the welcome. ‘I could not believe the crowds,’ she said, ‘It was the most amazing experience in my whole life, I thought they were cheering for someone standing behind me.’ The image of her kissing the side of Kingfisher as soon as she stepped on to the pontoon has become a particularly iconic moment in MacArthur’s sailing history. ‘The best thing in the race was crossing the finishing line, the hardest was leaving my boat,’ she explained. Soon afterwards she won the Yachtsman of the Year award for the second time.

Desjoyeaux was now the fastest ever solo circumnavigator and MacArthur the second. But soon after she finished the Vendée, she and Turner formulated a five-year plan that included an attempt at this solo non-stop round the world record. ‘Since being in the Southern Ocean in the Vendée,’ she said, ‘I’d been both enchanted by and drawn to its seductive beauty, and I knew I had to return there.’ However, she knew that she would need to attempt such a record in a multihull and she also knew that she had practically no multihull experience – that was something that she would start to address later in the year.

Her next race on Kingfisher was as co-skipper (with Nick Maloney, another normally-solo sailor supported by Ocean Challenges) in the fully-crewed EDS Atlantic Challenge, a five-leg race which started from Saint-Malo in July and involved two Atlantic crossings. Kingfisher won three of the five legs, and overall victory.

At the end of 2001, MacArthur again took part in the Transat Jacques Vabre two-handed race – again starting from Le Havre but this time finishing in Salvador de Bahia in Brazil, making it the first transatlantic race to cross the equator – with her good friend Alain Gautier on his ORMA 60 trimaran Foncia. They finished second in a fleet of fourteen boats.

At the London Boat Show in January 2002, MacArthur announced that she intended to challenge for the Jules Verne Trophy, and would be looking for a suitable boat and recruiting a crew to do so. This competition had been inaugurated in 1991 to see if any fully-crewed boat could sail around the world – starting and finishing on a line between the Lizard Point and Ushant – in under eighty days. The first boat to win the trophy was the catamaran Commodore Explorer, which completed her voyage in a little more than 79 days and 6 hours in 1993. At the time that MacArthur made her announcement, the record stood at 71 days and 14 hours – achieved by Oliver de Kersausen’s trimaran Sport Elec – but, shortly afterwards, Bruno Peyron’s catamaran Orange reduced it still further to 64 days and 8 hours. ‘The bar for us was undoubtedly raised higher,’ said MacArthur. However, it soon became apparent that Orange herself was available and so MacArthur’s sponsors, Kingfisher PLC, bought the boat, thus solving one of the major issues. However, this giant catamaran already need a serious refit, and matters got worse when, before MacArthur’s team was able to take her over, she was dismasted while sailing in the Mediterranean. Luckily, a spare tube section was readily available, although there was a fair amount of work involved to complete, rig and step it, and this work wasn’t completed until mid-December.

Meanwhile, MacArthur was racing her Open 60 Kingfisher for the last time, in the Route de Rhum. Once again, she won her class but this time she did so two days ahead of the record time and even finished before any of the multihull class, which had been decimated by appalling weather. It was the first time that a monohull had crossed the finish line first in the 24-year history of the Route de Rhum, which Yachting World described as ‘the race that confirmed her ascendancy as Britain’s finest offshore sailor’.

For her Jules Verne attempt, MacArthur had thirteen crew, four of whom knew Orange well as they had sailed on her with Peyron when breaking the record in 2002. This was a far cry from the single-handed and two-handed sailing that had dominated her sailing career to date, and she realised that much of it was a new experience for her.

With Orange re-named Kingfisher II, she moved from Cowes, where the refit work had taken place, to Lorient, which would allow easy access to the Atlantic during the short time available after the new rig was stepped. On 15 January 2003, the crew went on standby, awaiting news from their shore-based weather router that the conditions would be good to start. Just over a week later they were called back to the boat and, on 27 January, they set sail. On the way to the start line, around 100 miles away, they noticed that there was some damage to the mast track and so they headed to Plymouth to fix it. After a quick repair, they set off again and crossed the start line in gusts of 60 knots.

Not only would MacArthur and her crew be pacing themselves against Orange’s record, but also against another boat – the trimaran Geronimo, in which Oliver de Kersausen was trying to reclaim the record – which had started before them and was now heading into the Indian Ocean.

Just over three weeks later, Kingfisher II was, herself, about halfway across the Indian Ocean. After a relatively slow start, things had been going better for her: she had just overtaken Orange’s record pace and news had come through that Geronimo – which had been two days ahead of the record – was just past Cape Horn and beginning to slow. But, just before dawn on 22 February, when they were about 100 miles past the Kerguelen Islands, disaster struck. MacArthur was at the chart table at the time, discussing the weather with her shore-based weather router on the sat-phone, when she was ‘jolted forwards’ just as she heard a ‘gut wrenching, ear-piercing, crunching and snapping sound’. At first she thought that Kingfisher II had hit an iceberg but that was not the case: the mast had snapped.