Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

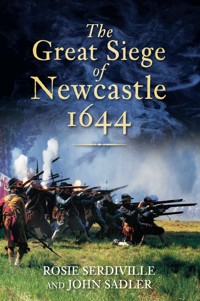

In the autumn of 1644 was fought one of the most sustained and desperate sieges of the First Civil War when Scottish Covenanter forces under the Earl of Leven finally stormed Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the King's greatest bastion in the north-east and the key to his power there. The city had been resolutely defended throughout the year by the Marquis of Newcastle, who had defied both the Covenanters and northern Parliamentarians. Newcastle had held sway in the north-east since the outbreak of the war in 1642. He had defeated the Fairfaxes at Adwalton Moor and secured the City of Newcastle as the major coal exporter and port of entry for vital Royalist munitions and supply. Without this the north was lost. If anything, Newcastle was more important, in strategic terms, than York and it was the city's fall in October which marked the final demise of Royalist domination of the north. The book tells the story of the people who fought there, what motivated them and who led them there. It is also an account of what happened on the day, a minute-by-minute chronicle of Newcastle's bloodiest battle. The account draws heavily on contemporary source material, some of which has not received a full airing until now.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TheGreat SiegeofNewcastle1644

TheGreat SiegeofNewcastle1644

ROSIE SERDIVILLEAND JOHN SADLER

Dedicated to all Time Bandits, past and present

Cry, valiant soldiers, laid not your arms,

Listen to the whispers of the night.

Look into your heart and seek,

Find the truth and fight.

Let not your courage be meek.

Like the lion roar.

Worthy your part play, comrades, when battle has begun,

Loosen the dogs of war.

Death shall be your only song,

And like the brave, shall leave their mark in a lonely grave.

Jennifer Laidler

First published 2011

The History PressThe Mill, Brimscombe PortStroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved© Rosie Serdiville and John Sadler, 2011, 2013

The right of Rosie Serdiville and John Sadler to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5349 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

Timeline

Dramatis Personae

Glossary

1.

Being Introductory

2.

Laud’s Liturgy

3.

The Gathering Storm

4.

War in the North 1642–3

5.

The Winter War 1644

6.

No Coals from Newcastle – Autumn 1644

7.

Storming the Walls – 19 October 1644

8.

Aftermath – Fortitur Triumphans Defendit

Appendix 1: The Art of War in the Seventeenth Century

Appendix 2: Siege Warfare

Appendix 3: The Scots Army

Appendix 4: The Battlefield Trail Today

Appendix 5: The Storming of Newcastle – Poem

Appendix 6: Mapping the Wars

Appendix 7: The Order to Reduce Newcastle

Notes

Select Bibliography

Preface

As a boy, youth and young man, one of the co-authors spent many hours inside Newcastle Keep, that great dark tower so anachronistically placed, surrounded by the rush and consequence of a much later and dismissive era. It has withstood several centuries of Scottish raiders, their Tudor reiver descendants, the ravaging of civil wars, a brash Industrial Revolution and the neglect of contemptuous progress. Relatively few medieval citadels survive in our major cities, the White Tower of London being almost certainly the grandest.

Newcastle’s keep was already old when King Charles I raised his standard at Nottingham in that distant summer of 1642, thereby igniting a conflict that would rage and then splutter for another eighteen years till, after a vast effusion of blood and treasure, his son ascended a throne vacant since the regicide of 1649. It would be reasonable to assert that none of those who embarked upon the course of civil strife intended, at that point, to kill the King and establish a republic. Their aims were far more conservative and the vast majority of Parliamentarians would have recoiled from being tarred by any revolutionary brush. It was intended that the royal prerogative be curtailed, rather than cut off. None who marched in the early days behind Parliament’s banner had any notion of redistributing wealth. The wars were fought more for control than for radical change. Many would be astonished by the changes strife engendered, less than happy with the consequences and the rise of radical sectaries. Many would be surprised by their own actions – few of the regicides, for example, would have ever contemplated at the outset that they might feel themselves finally driven down such a path. We should not lose sight of the fact that, considering the size of our population in the mid-seventeenth century, the Civil Wars took, pro rata, a worse toll than even the First World War.

The Great Siege and Storming of Newcastle in the autumn of 1644 was an important episode in significant period during the First Civil War (1642–46) and yet it is one which is largely forgotten. This modern study of the siege seeks to shed light upon the nature of polity and division within urban communities and how local factors influenced and shaped allegiances. In the case of Newcastle this led to a tragic and ultimately futile campaign that could have only one outcome. It is said that the term ‘Geordies’ was coined during a later conflict, the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion, when the Newcastle miners and artisans were so universally Whig in sentiment they drowned out calls for ‘King James’ with cheers for King George or Geordie. This appears a fundamental shift from the position some sixty years earlier when the city was so resolutely held for the exiled Stuart’s father. Yet the situation on Tyneside during the Civil Wars was by no means as clear cut or so demonstrably partisan as might, at first glance, appear to be the case.

The late Professor Terry, who published a series of erudite papers in Archaeologia Aeliana in the closing years of the nineteenth century and was a distinguished scholar who had done much work on the army of the Covenanters, provided a detailed study of the primary source material. An interesting local work had earlier been complied in 1889 and subsequently reprinted in 1932 under the title The Siege and Storming of Newcastle. Most of the recent writers on the military aspects of the Civil Wars have neglected both the winter campaign in the north east during those early snowbound months of 1644 and the subsequent autumn siege and storming. Even Gardiner in his great history, provides us with scant detail. A more recent and local historian, Stuart Reid, who is a constant and accomplished student of the pike and shot era, has written a carefully researched and lucid account of the campaigns of 1644 but does not shed light upon the subsequent siege.

For the enthusiast and collector of battlefields the city holds many traces, some of which still rise unscathed from the post-industrial detritus around. The Civil War tour is more fully discussed in appendix two. This co-author can claim to have had a long association of involvement with the Keep as both father and father-in-law were representatives of the Society of Antiquaries with responsibility for fabric and collections and he spent some school summers in anorak heaven cleaning and displaying arms and armour. Without that, perhaps this history might not have been written.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due from the authors to Anna Flowers and colleagues from Newcastle City Libraries, Colm O’ Brien and other colleagues at the North East Centre For Lifelong Learning, Nicky Clarke and members of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne, the staff of the Great North Museum, the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle upon Tyne, Liz Ritson, Jo Raw and staff at Woodhorn County Museum and Archive, Adam Goldwater and Gillian Dean of Tyne and Wear Museums, Bill Griffiths of the Museums Hub, Tony Ball of Newcastle Keep, Robert Cowper, the late Professor George Jobey, the late Alec Bankier, Charles Wesencraft, Dr Jo Bath, Bill and Diane Pickard, Sarah-Jayne Goodfellow, Diane Trevena, Doug Chapman, Tony Hall and Lyn Dodds, to Adam Barr for the photographs, Jennifer Laidler for the verse extracts and Chloe Rodham for the maps; another successful collaboration. For all errors and omissions the authors remain, as ever, responsible.

Quotes from Napoleon’s maxims are taken from the late Dr David Chandler’s The Military Maxims of Napoleon (Greenhill: London, 2002).

All pictures are from the author’s collection unless otherwise stated.

Timeline

1625–39

June 1625 – Charles I of England marries Catholic Henrietta Maria, daughter of Henry IV of France

May 1626 – Charles dismisses Parliament

March 1628 – Parliament recalled; issue of the Thirty Nine Articles

7 June 1628 – Petition of Right

22 August 1628 – James Villiers, Duke of Buckingham is murdered

March 1629 – The Three Resolutions; nine MPs arrested

1632 – Thomas Wentworth (‘Black Tom Tyrant’ & latterly Earl of Strafford) is appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland

August 1633 – William Laud is appointed Archbishop of Canterbury

18 June 1633 – Charles is crowned King of Scotland in Holyrood Palace

1634–6 – Imposition of Ship Money

February 1638 – Attempted imposition of ‘Laud’s Liturgy’; Scots enter into Solemn League and Covenant

June 1638 – John Hampden tried for refusing to pay Ship Money

1639 – The pacification of Berwick; First Bishops’ War ended

1640

13 April – The Short Parliament

28 August – The Rout of Newburn Ford

21 October – Treaty of Ripon

November – The Long Parliament

1641

20 May – Execution of Strafford

Summer – Triennial Act

Late summer – Rebellion in Ireland breaks out

22 October – Catholic revolt in Ireland

November – The Grand Remonstrance

1642

4 January – Attempt to arrest the five members

March – The Militia Ordinance

April – Charles before the gates of Hull

June – The Nineteen Propositions

July – First Siege of Hull

22 August – Charles raises the royal standard at Nottingham; the Civil War begins

23 September – Skipton Castle besieged

23 October – Battle of Edgehill

13 November – Charles halts before the Parliamentarian forces at Turnham Green

1643

27–29 February – Newark attacked by Ballard

13 April – Battle of Ripplefield

18 June – Skirmish at Chalgrove Field (John Hampden killed)

23 June – Battle of Adwalton Moor

13 July – Battle of Roundaway Down

July – Chester besieged

10 August – Gloucester besieged

20 September – First Battle of Newbury

25 September – Scots enter into Solemn League and Covenant

11 October – Battle of Winceby

November – Basing House besieged and relived

29 November – Anglo-Scottish Treaty formalised

25 December – Pontefract besieged by Lord Fairfax

1644

19 January – Scots cross the border into Northumberland

25 January – Battle and relief of Nantwich

28 January – Scots at Morpeth

3 February – Scots storm the Shieldfield Fort

19 February – Skirmish at Corbridge

1 March – Pontefract again besieged

March – The Wearside Campaign

21 March – Prince Rupert relieves Newark

22 April – Marquis of Newcastle besieged in York

10 May – Montrose and the Earl of Crawford launch unsuccessful attack on Morpeth Castle

29 May – Morpeth surrenders to the Royalists

June – Rupert lays siege to and captures Liverpool

25 June – A further Scottish force under Callendar crosses the border

24 July – Battle of Marston Moor

27 July – Scots return north, leaguer of Newcastle begins

August–October – Siege of Newcastle

19 October – Storming of Newcastle

Dramatis Personae

John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse (1615–1689)

The second son of the 1st Viscount Fauconberg, North Riding gentry and staunch Catholic. He joined the King’s Oxford army having raised a regiment of horse and taken command of his father’s foot regiment. He fought at Edgehill and the First Battle of Newbury before being transferred to Newcastle’s army early in 1644, taking control of York when the marquis moved north to confront the Scots. He was left with the unenviable task of containing the resurgent Fairfaxes with slender resources. Having lost Bradford, he was captured in the Parliamentarian assault at Selby on 11 April, remaining a prisoner till January 1645.

William Cavendish, Marquis of Newcastle (1593–1678)

A grandson of the formidable Bess of Hardwick. In his youth, more famed for his equestrian and fencing skills than academic achievement, he was nonetheless a distinguished member of a glittering scientific circle in the 1630s. On the death of his father in 1613 he inherited the Cavendish estates, was created Viscount Mansfield in 1620 and Earl of Newcastle eight year later. He was, on his mother’s side, a representative of the old Northumbrian Ogle line. An accomplished courtier who expended vast sums in support of the King, he was governor to the Prince of Wales. No soldier, his service in the Bishops Wars was marked only by his hostility to the Earl of Holland. He raised his famous tercio of Whitecoats to serve Charles in the north, where he was placed in charge of Royalist forces with military advice from a number of experienced captains such as Goring, Langdale and Eythin (see p. 13). In June 1642, he was elevated to his Marquisate and defeated the Fairfaxes resoundingly at Adwalton Moor. He fled the realm after Marston Moor only returning with the Restoration.

Sir Hugh Cholmley, 1st Baronet (1600–1657)

Elected as MP for Scarborough in 1624, his regiment fought at Edgehill. Subsequently defected from Parliament’s side and was appointed as a local commander by the Earl of Newcastle with responsibility for the northern section of the Yorkshire coast. After the disaster at Marston Moor, he continued to hold Scarborough for the King before surrendering in July 1645. His final years were spent in exile.

Edward Conway, 2nd Viscount Conway, 2nd Viscount Killultagh (1594–1655)

Son of the 1st Viscount. An Oxford scholar, he studied the art of war under the aegis of his uncle by marriage, Sir Horace Vere and served several terms as MP for Warwick. He was moved to Ireland after the debacle at Newburn in 1640.

Sir John Digby, 1st Earl of Bristol (1580–1653)

Scion of Warwickshire gentry and educated at Cambridge, Digby embarked upon a diplomatic career acting as ambassador to Spain from 1611–24. He failed to broker a Spanish alliance and, though raised to his earldom in 1622, fell foul of the King and spent several years as a prisoner before being released through Parliament’s intervention. Though he agreed with some aspects of parliamentary reform, he remained a Royalist at heart and was imprisoned by them in turn. He died in exile.

Ferdinando, 2nd Lord Fairfax (1584–1648)

Fairfax, whose seat was at Denton Hall in Wharfedale, has always been rather overshadowed by the achievements of his eldest son Sir Thomas (see below). He did, however, serve a military apprenticeship in the Netherlands before serving Charles I in the First Bishops’ War. He was essentially a moderate though opposed to abuses of the Prerogative and remained steadfast in his allegiance to Parliament.

Sir Thomas, 3rd Lord Fairfax (1612–1671)

‘Black Tom’ was the first Lord General of the New Model Army and led them to decisive victory at Naseby. Upright, chivalrous and honourable, a lion in battle, though somewhat inclined to hypochondria, he was less sure in politics where his moderation became unfashionable, leading to a distance between he and Cromwell. He survived the Restoration and ended his days in quiet seclusion.

Sir Thomas Glemham (1594–1649)

A scion of Suffolk gentry, Glemham served his military apprenticeship in Europe from 1610–17. He served in Buckingham’s ill-conceived expedition to La Rochelle then acted as governor of Hull, accompanying Charles I on his abortive attempt to gain control of the city. He next governed York before being sent north in November 1643 to watch the border, falling back before Leven’s army in January 1644. After the Sunderland campaign and Newcastle’s withdrawal into York he resumed the governorship, remaining proactive during the siege. After Marston Moor was lost he was left with skeleton forces and a hopeless position. Nonetheless, he managed to negotiate remarkably lenient terms. Thereafter he continued to serve the King as governor of Oxford. He died in exile in Holland.

Lord George Goring (1608–1657)

Perhaps the very ideal of the beau sabreur – a popular and dashing cavalier. Born of Sussex gentry, he married an Irish heiress in 1629 but squandered most of her cash on drink and dice. He served with some distinction in the Netherlands and was elected MP for Portsmouth. Regarded as a Parliamentarian, he was given responsibility for the defence of the city but declared for the King once the standard had been raised. He defeated Fairfax at Seacroft Moor but was subsequently captured and held in the Tower until being exchanged in spring 1644. He was able to join Rupert in time to fight well and with all his customary dash at Marston Moor. His career then entered a downward spiral and he died, penniless in Madrid at the age of forty-nine.

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose (1612–1650)

Montrose is one of the most renowned and quixotic figures of the Civil Wars. He inherited his lands and title from his father on the latter’s death in 1626. An advocate of the Covenant, he served the Estates well until his allegiance to the King proved too strong. Disregarded by Rupert he nonetheless went on to campaign successfully in Scotland during the ‘Year of Miracles’. This came to an abrupt and bloody finale when he was defeated by David Leslie at Philliphaugh. He never regained his former glory and died an ignominious death at the vengeful hands of his former allies. His legend, however, persists.

James King, Lord Eythin (1589–1652)

An Orcadian by birth, King was a natural grandson of James V. He learned his trade under Gustavus and then Leslie where he served with some merit. He was never in step with the Covenanters, leaning towards the King. He served Newcastle as a competent chief of staff though, after January 1644 and Leslie’s invasion, he was treated with some suspicion. This festered at York where his marked antipathy to Rupert proved damaging. He died in exile in Sweden.

Sir Marmaduke Langdale (1598–1661)

Born in Beverley, Langdale fought in the Palatinate, receiving his knighthood in 1628. A leading member of the Yorkshire gentry, he opposed the Ship Tax but was still trusted by the King and created Lord-Lieutenant of the shire in 1639. A loyal cavalier, he retained command of Newcastle’s cavalry units after Marston Moor. Brigaded as the Northern Horse, they noted for their dash and fire if not for their discipline.

Alexander Leslie, Earl of Leven (1580–1661)

Despite being illegitimate, Leslie pursued an active military career from an early age, serving in the Dutch Wars and then with great distinction under Gustavus. He fought at Lutzen in 1632, where his patron was killed. Despite this, he continued to serve under Queen Christina and remained until 1636, when he retired as a full field marshall. On returning to Scotland, and regarded as the nation’s leading soldier, he was the natural choice to command the Covenanter army. In the Second Bishops’ War he showed masterly skill in routing the King’s forces at Newburn Ford and taking Newcastle. He returned at the head of the army in January 1644 and had conduct of the campaign in the north. He commanded all Parliamentarian forces at Marston Moor but then and thereafter he failed to display his former energy, clearly suffering from the rigours of campaigning. He went on to command Parliament’s forces during the siege and storming of Newcastle.

David Leslie, 1st Newark (1600–1682)

The son of the 1st Earl of Lindores, he was the nephew of the Earl of Leven. Leslie learned his profession in the Swedish service and acted as Leven’s second in command in 1644. His cavalry did good service at Marston Moor and it was he who finally cornered and defeated Montrose at Philiphaugh, though the victory was soured by atrocity. He fought for Charles II after 1650 and hemmed Cromwell into the Port at Dunbar. Interference from covenanting clergy affected his ability to command and provided an opportunity for Cromwell to strike and win what was perhaps his greatest victory.

John Lilburne (1613?–1657)

Known as ‘Freeborn John’, Lilburne was a native of Bishop Auckland who attended Newcastle’s Royal Grammar School. He became a celebrated agitator and pamphleteer. Flogged and imprisoned by the King, he fought with some distinction for Parliament at Edgehill, was subsequently captured and exchanged, next serving with the Eastern Association. He was an intimate of Cromwell’s, though no favourite of Manchester who considered him a dangerous lunatic. His libertarian and Leveller view put him at odds with Cromwell after the Putney Debates and most of his later years were spent in gaol though he was increasingly paroled as his religious views softened and he became a Quaker. He died of fever probably at the age of forty-two.

James Livingston, Lord Almond & 1st Earl of Callendar (d.1674)

The third son of the 1st Earl of Linlithgow, Livingston learnt his trade in the Dutch Wars but never learned to love the covenant. He served Leslie as chief-of-staff in the Second Bishops’ War but sided later with Montrose and signed the Cumbernauld Bond. He was reconciled to the King in 1641, but despite doubts over his loyalties served Leslie again after the latter led the army into England in 1644. He remained in charge of reserves stationed on the border till marching south in June. There were mutterings over his alleged reluctance to fight against Montrose but he served his commanding general throughout the blockade, siege and storming of Newcastle.

Sir John Marley (1590–1672)

A staunch and unrepentant Royalist, Marley famously defended Newcastle as mayor in 1644. His uncompromising stand seems to have earned the resentment not just of the Scots but also of many less committed townsfolk. He escaped from custody (or was allowed to escape) into exile but may have returned as early as 1658 to facilitate the Restoration. He again served as mayor in 1661.

Sir Henry Slingsby (1602–1658)

A Yorkshire landowner and West Riding MP, related by marriage to Belasyse, he fought in the Bishops’ Wars and officered the queen’s escort from Bridlington. He fought for the King at both Marston Moor and Naseby, remaining a convinced Royalist. He plotted to overthrow Cromwell and was involved in a scheme to seize Hull. When this was uncovered he was tried and subsequently executed.

Henry Wilmot, 1st Earl of Rochester (1612–1658)

A constant and successful Royalist, Wilmot learned the art of war in Holland, where he served with Goring. After service in the Bishops’ Wars he pursued a distinguished career as a Royalist officer, participating in many actions, beginning with Powicke Bridge though he could not get along with Prince Rupert. His finest hour was victory over Waller and the virtual destruction of Parliament’s western forces at Roundway Down. His later career was controversial but always colourful. He died of fever at Sluys in Flanders.

Sir Henry Vane (1589–1655)

A Kentishman by birth, Vane qualified at the Bar and was knighted by James I. Able and ambitious, he bribed his way into a string of political offices, rising to high favour with Charles I, who entrusted him with a series of high-level diplomatic missions. He subsequently quarrelled with Strafford and was a prosecution witness at the latter’s trial. After the setback of the Second Bishops’ War, he retained the King’s confidence but subsequently fell from grace and defected to Parliament. His accumulation of wealth in the 1630s had enabled him to acquire Raby, Barnard Castle and Long Newton in Durham. He remained high in Parliament’s counsels though no friend to Lilburne and the Levellers. There was a suggestion that his death was suicide.

Glossary

Abatis – Improvised defences of cut branches planted points outwards toward an enemy, sixteenth-century barbed wire

Ambuscade – Trap or ambush

Backsword – A form of weapon with one sharpened cutting edge and the other flattened and blunt, primarily a horseman’s weapon designed for the cut

Banquette – Earth step within the parapet which allows the defenders to fire

Barbican – A form out defended outer gateway designed to shield the actual gate itself

Bartizan – A small corner turret projecting over the walls

Bastion – Projection from the curtain wall of a fort, usually at intersections, to provide a wider firing platform and to allow defenders to enfilade (flanking fire) a section of the curtain

Batter – Outward slope at the base of a masonry wall to add strength and frustrate mining efforts

Battery – A section of guns, may be mobile field artillery or a fixed defensive position within a defensive circuit

Blinde(s) – A bundle of brushwood or planks used to afford cover to trenches

Brattice – A temporary series of timber hoardings affording extra cover for defenders

Breast and back – Body armour comprising a front and rear plate section

Breastwork – Defensive wall

Broadsword – A double-edged blade intended for cut or thrust, becoming old-fashioned though many would do service, often with an enclosed or basket hilt

Buff Coat – A leather coat, long skirted and frequently with sleeves, fashioned from thick but pliant hide, replaced body armour for the cavalry

Caliver – A lighter form of musket, with greater barrel length than the cavalry carbine (see below)

Cannon – Heavy gun throwing a 47lb ball; a demi-cannon fired 27lb ball; cannon-royal shot a massive 63lb ball

Caracole – A form of cavalry tactic whereby the riders approach the enemy infantry in ranks, discharging pistols then wheeling aside before contact

Carbine – A short barrelled musket used primarily by cavalry

Case-shot – Also referred to as canister this was a cylindrical shell case, usually tin, sealed in beeswax and caulked with wooden disks, wherein a quantity of balls were packed and filled with sawdust. A cartridge bag of powder was attached to the rear and, on firing, the missile had the effect of a massive shotgun cartridge, very nasty

Casement – A bomb-proof chamber or vault within the defences

Chevaux-de-frise – A large baulk of timber set with sharpened blades to form an improvised defence, often employed to seal or attempt to seal a breach in the defender’s walls

Clubmen – Bodies of local men who formed associations of militia to defend their localities against incursions by forces from either of the warring factions – armed neutrals

Commission of Array – This was the ancient royal summons issued through the lords-lieutenants of the counties to raise militia forces, in the context of a civil war such an expedient was of dubious legality as it was clearly unsanctioned by Parliament

Committee of Both Kingdoms – This was brought into being as a consequence of two parliamentary measures (16 February and 22 May 1644) to ensure close cooperation between the English and Scots, Cromwell, Manchester and Essex were all members of the Committee which sat at Derby House

Cornet – A pennant or standard and thus also the junior officer who carried it

Corselet – This refers to a pikeman’s typical harness of breast and back, with tassets for the thighs

Counterscarp – Outer slope or wall of a defenders’ external ditch or moat

Covered Way (or Covert) – A covered or protected position, usually a lowered earth parapet on the counterscarp of an outer glacis

Cuirassier – These were heavy cavalry wearing three-quarter harness, something of an anachronism. Sir Arthur Hesilrige’s ‘Lobsters’ were the most famous example; as the wars progressed reliance upon armour decreased considerably

Culverin – A gun throwing a 15lb ball. Mainly used in siege operations, the guns weighed an average of 4,000lb the lighter demi-culverin threw a 9lb ball and weighed some 3,600lb

Dagg(s) – Wheel-lock horseman’s pistols, usually carried in saddle holsters

Dragoon – Essentially mounted infantry, the name is likely derived from ‘dragon’ a form of carbine; their roles was to act as scouts and skirmishers and they could fight either mounted (rare) or dismounted

Defilade – Where one party, probably a defender, uses any natural or man-made obstacle to shield or conceal their position (see also enfilade below)

Drake or Saker – Gun firing a 5¼lb ball

Enceinte – The circuit or whole of the defensive works

Enfilade – Where one party is in a position to direct fire onto the longest exposed axis of the other’s position, e.g. an attacker is able to shoot along a defender’s trench from the flank

Ensign (or Ancient) – A junior commissioned officer of infantry who bears the flag from which the name derives

Falcon – Light gun firing a 2¼lb ball

Falconet – Light gun throwing a 1¼lb shot

Field-works – A system of improvised temporary defensive works employed by an army on the march or protecting an encampment

Fleche – A projecting V-shaped defensive outwork

Flintlock or firelock – A more sophisticated ignition mechanism than match; the flint was held in a set of jaws, the cock, when released by the trigger, struck sparks from the steel frizzen and showered these into the pan which ignited the main charge

Foot – Infantry

Free Quarter – Troops paying for food and lodgings by a ticket system, requisitioning or outright theft in practice

Fusil – This was a form of light musket usually carried by gunners and latterly by officers, hence ‘fusilier’

Gabion – Wicker baskets filled with earth which formed handy building blocks for temporary works or sealing off a breach

Glacis – A sloped earthwork out from the covered way to provide for grazing fire from the curtain

Granado – Mortar shell

Guns – Artillery

Halberd – A polearm, outdated in war but carried as a staff of rank by NCOs

Harquesbusier – An archaic term describing the cavalryman armed with carbine, sword and brace of pistols, the latter sometimes still referred to as ‘daggs’

Horse – Cavalry

Linstock – A staff with a forked end to hold match – used for discharging cannon

Lunette – Flanking walls added to a small redan (see below) to provide additional flanking protection and improved fire position; a ‘demi-lune’ is a crescent or half moon structure built projecting from the curtain to afford greater protection

Magazine – Bomb-proof vault where powder and shot are stored

Main Gauche – Literally ‘left hand’; this was a form of dagger used in conjunction with the rapier

Matchlock – The standard infantry firearm, slow and cumbersome, prone to malfunction in wet or wind, it was nevertheless generally reliable. When the trigger was released the jaws lowered a length of lit cord ‘match’ into the exposed and primed pan which flashed through to the main charge, where the charge failed to ignite this was referred to a ‘a flash in the pan’

Matross – A gunner’s mate, doubled as a form of ad hoc infantry to protect the guns whilst on the march

Meutriere – Or ‘murder-hole’, a space between the curtain and corbelled out battlements enabling defenders to drop a variety of unpleasant things onto attackers at the base of the wall

Minion – Gun shooting a 4lb ball

Morion – Infantry protective headgear, the morion was a conical helmet with curving protective brim and central ridged comb intended to deflect a downwards cut

Musket – The term refers to any smooth-bored firearm, regardless of the form of lock, rifled barrels were extremely rare, though not unknown at this time

Ordnance – Artillery

Pike – A polearm with a shaft likely to be between 12 and 18ft in length, finished with a diamond-shaped head (see appendix 1)

Postern (Sally Port) – A small gateway set into the curtain allowing re-supply and deployment of defenders in localised attacks on besiegers

Rapier – A slender, long-bladed thrusting weapon, more likely to be owned by gentry; bespoke and more costly than a trooper’s backsword

Shot – Musketeers

Ravelin – A large, V-shaped outwork, beyond the ditch or moat, intended to add protection to a particularly vulnerable point

Redan – Smaller than the ravelin, this is a small outwork with two walls set at a salient angle facing the enemy, typically the rear or gorge is uncovered, similar to a fleche

Redboubt – A detached, square, polygonal or hexagonal earthwork or blockhouse

Robinet – Light field gun firing a 1¼lb shot

Scarp – Inner wall of ditch or moat

Sconce – A small detached fort with projecting corner bastions

Snap – Cold rations carried in a ‘snapsack’

Swine-Feather – Also known as Swedish feathers, a form of metal-shod stake that could be utilised to form an improvised barrier against an enemy

Tasset – A section of plate armour hinged from the breastplate intended to afford protection to the upper thigh

Tercio – A Spanish term for the military formation, derived from the Swiss model which dominated Renaissance warfare, developed into a more linear formation after the reforms of the Swede Gustavus Adolphus

Terreplein – A level space upon which defenders guns are mounted

Touch-hole – The small diameter hole drilled through the top section of a gun barrel through which the linstock ignites the charge, fine powder was poured in a quill inserted into the touch-hole

Train – A column of guns on the move, the army marches accompanied or followed by the train

Trained Bands – Local militia

Wheel-lock – More reliable and much more expensive than match, this relied upon a circular metal spinning wheel wound up like a clock by key. When the trigger was released the wheel spun and the jaws lowered into contact and fitted with pyrites, showered sparks into the pan

1

Being Introductory

The Forward Youth that would appear

Must now forsake his muses dear,

Nor in the shadows sing

His number languishing

Tis time to leave the books in dust,

And oil the unused armour’s rust,

Removing from the wall

The corslet from the hall.

‘An Horatian Ode upon Cromwell’s return from Ireland’ Andrew Marvell (1621–1678)

The first consideration with a general who offers battle should be the glory and honour of his arms; the safety and preservation of his men is only the second; but it is in the enterprise and courage resulting from the former that the latter will most assuredly be found.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Into the Breach

On the afternoon of 19 October 1644, a grey day of autumn, smoke eddied over the scorched walls of the northern city and the jumble of close-packed buildings gapped and scarred by shell. Civil strife, unseen in England since Bosworth and Stoke Fields more than a century and a half ago, was now enjoying a full, bitter flowering. In part this was an ancient grudge, Scots and Northern English, honed by three full centuries of bitter hate and constant strife, from snarling lancers with border names, to crack of cannon and the clothyard storm on a dozen bloodied fields and more.

The attackers shuffled out into columns, a drab legion in ragged hodden grey, morion and corselets scoured to a dull glow. Dry-mouthed, each man stood, waiting, while dour ministers moved along the columns offering the solace of God’s word.

Above, the cannonade reached a fury. Great black clouds of sulphurous fumes obscured the lines already half hidden by camp followers burning rubbish, the ancient Scots’ smoke screen. Trumpets blared and the assault started, men stumbling forward hefting the ungainly weight of puissant pike or blowing on match, officers drew swords.

It was begun.

The Great Cause