9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

10 September 1961: at the boomerang-shaped racetrack at Monza, in northern Italy, half a dozen teams are preparing for the Italian Grand Prix. It is the biggest race anyone can remember. Phil Hill - the first American to break into the top ranks of European racing - and his Ferrari teammate, Count Wolfgang von Trips - a German nobleman with a movie-star manner - face each another in a race that will decide the winner of the Formula One drivers' championship. By the day's end, one man will clinch that prize. The other will perish face down on the track. In The Limit, Michael Cannell tells the thrilling story of two parallel lives that come together in tragedy on a hot late-summer afternoon. He charts their careers from childhood and adolescence lived in the shadow of world war### through their gruelling experiences in such deadly road races as the Mille Miglia and the 24 Hours of Le Mans; to their coming of age in the hothouse atmosphere of Enzo Ferrari's Formula One team of the late 1950s. The quiet and self-contained Hill was a pathological worrier who vomited before a race and enjoyed Bartok and Shostakovich - rather than Campari and debauchery - thereafter; the dashing von Trips lived life as fast as he drove his 'sharknose' Ferrari, and yearned to inspire a nation fractured and traumatized by war. Both men strove to attain the perfect balance of speed and control that drivers called 'the limit': to drive under that limit was to run the risk of failure; to go beyond it was to dice with death. The Limit is a vivid and atmospheric recreation of a lost world of seductive glamour and ever-present danger. Michael Cannell tells a moving and unforgettable tale of high speed and burning rivalry - and of young lives lived in the shadow of oblivion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

THE

LIMIT

ALSO BY MICHAEL CANNELL

I. M. Pei: Mandarin of Modernism

THE

LIMIT

Life and Death in Formula One’s Most Dangerous Era

MICHAEL CANNELL

First published in hardback and export trade paperback in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Michael Cannell, 2011

The moral right of Michael Cannell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 184887 222 6 Export and Airside trade paperback ISBN: 978 184887 223 3 E-book ISBN: 978 085789 419 9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Evie and Cricket

Contents

Prologue

1. An Air of Truth

2. A Song of Twelve Cylinders

3. This Race Will Kill Us All

4. The Road to Modena

5. Pope of the North

6. Count von Crash

7. Garibaldini

8. Ten-Tenths

9. Birth of the Sharknose

10. 1961

11. Pista Magica

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Speed provides the one genuinely modern pleasure.

—Aldous Huxley

In Morte Vita (In Death There Is Life)

—the von Trips coat of arms

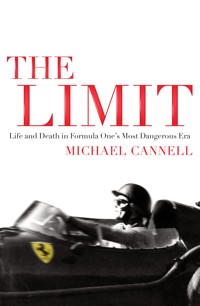

Phil Hill leads a procession of Ferraris on the notorious banking at Monza, site of the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. “This was a duel in the sun,” a correspondent wrote, “and the pace was too hot to last.” (Cahier Archive)

Prologue

THEY BEGAN ARRIVING a day in advance. The loyal Ferrari following—the tifosi—rolled up in caravans of Fiats and battered motorbikes to camp among the chestnut groves that spread more than six hundred acres around the boomerang-shaped racetrack in Monza, Italy. By the glow of evening campfires they raised cups of grappa to the great drivers, the piloti who once thundered around the terrible banked turns of the Autodromo Nazionale looming at the edge of the woods like a concrete cathedral.

Most of those piloti were gone now. Between 1957 and 1961 twenty Grand Prix drivers died. Many more suffered terrible injuries. By some estimates, drivers had a 33 percent chance of surviving. In the days before seat belts and roll bars, they were crushed, burned, and beheaded with unnerving regularity. One driver retired after winning the championship only to die three months later in an ordinary car accident near his home.

The survivors raced on, in spite of the ominously long death roll. Inside the autodromo half a dozen teams and thirty-two drivers warmed up for the 267-mile Italian Grand Prix, the climactic race of the 1961 season, with the spotlight focused squarely on Ferrari teammates Phil Hill and Count Wolfgang von Trips. The next afternoon, on Sunday, September 10, they would settle their long fight for the Grand Prix title, racing’s highest laurel. One last race remained, the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, New York, but Monza was expected to decide the back-and-forth battle between the two men.

Von Trips held a four-point edge, and he had earned the advantageous pole position with the fastest practice laps. His easy, agreeable manner gave him the air of an inevitable winner. He had the comportment of a champion. On the other hand, he had crashed twice at Monza over the previous five years. Either could have ended his career—or killed him. He had recovered, but the accidents clung to him like a curse. By comparison, Hill had won at Monza a year earlier, and he had set several lap records. If von Trips was the erratic star, Hill was his rock-steady complement. Like any great sports story, it was a pairing of opposites.

The two men had traded checkered flags all summer as the Grand Prix made its way through six European countries. Their contest reached manic proportions, just as Borg vs. McEnroe and Ali vs. Frazier would in the following decades. It played large on the front pages of European newspapers. “This was a duel in the sun,” the Times of London wrote on the eve of the race, “and the pace was too hot to last.”

Neither man was Italian, which suited Enzo Ferrari, the reclusive white-haired padrone of the Ferrari empire. Every time an Italian driver died the government launched a meddlesome investigation and the Vatican made thunderous condemnations.

The rivalry was made vivid by their polar personalities—the American technician versus the German nobleman, loner versus bon vivant, backstreet hot rodder versus Rhineland count. Each would be the first from his country to earn the title after the war. Each considered himself a nose faster.

The location only heightened the suspense. The Italians called Monza the Death Circuit, in part because the banked turns catapulted errant cars like cannonballs. The sloped surface was coarse and pockmarked, and it exerted a centrifugal pull the fragile Formula 1 cars were not designed to handle. (The British teams had boycotted Monza in 1960 because they judged the banking too perilous.) More dangerous still, the long straights allowed drivers to touch 180 mph, and to slipstream inches apart. A series of tight curves, known as chicanes, had been installed to slow the cars, but it was still a track to be driven flat out. As much as any racetrack in the world, it conjured racing’s heroics and horrors. To the north, it curved into a silent forest that was haunted by its many victims (or so went the legend).

The sun rose on a perfect cloudless Sunday with pennants snapping in a brisk breeze. The racetrack was bathed in soft September light. The pale outline of the Alps was visible to the north, glimpsed between a pair of Pirelli scoreboard towers. By afternoon the tifosi had gathered thirty deep at trackside railings, singing and drinking Chianti. They were jubilant in the promise of seeing the Italian cars humble the British—the hated Brits who had dominated the podiums over the previous few years with a new breed of lightweight, agile cars. Now the Italians were again ascendant, the British in retrograde. The anticipation was exceptional, even by the feverish standards of Grand Prix.

Down below, in the pits, mechanics clenching spanner wrenches and screwdrivers scurried around a fleet of low-slung single-seat cars painted national racing colors—red for Italian teams, green for Great Britain, silver for Germany—with no corporate logos to obscure them. Within a few years media handlers and sponsorship deals would inundate Grand Prix, setting it on its course to becoming the formidable business it is today, but in 1961 racing was more about nationalism than money. Though never stated explicitly, it was animated by dark, hawkish undercurrents. Ancient grudges were avenged with checkered flags. Young men died in the most advanced machinery their countries could devise, as they had in World War II.

The memories of the war, now sixteen years past, were increasingly overtaken by Cold War apprehension. Two weeks before the Monza race, Communist officials had sealed the border between East and West Berlin with concrete and barbed wire. Almost overnight it became a hair-trigger world fraught with spy planes and satellites, intercontinental H-bombs, and an emergent space race. Phil Hill recognized the sport’s ominous undercurrent. He and von Trips were, he said, gladiators in “an age of anxiety.” For his part, von Trips knew that the pageantry of a Grand Prix title would provide a unifying lift for his fellow Germans. Countries have a way of creating the hero they need, and von Trips fit the part.

The two men cleared their minds as mechanics rolled their red cars into formation. They lowered themselves into reclined seats made to their specifications, their legs reaching through the fuselage for pedals. Their shoulders pressed tightly against wraparound windscreens and their gloved hands clenched and unclenched small leather-padded steering wheels. Gauges jumped to life as the engines fired. Finely wrought Italian cylinders thrummed in staccato and a hornet shriek of exhaust resounded off the heaving grandstands. Smoke billowed behind them. They were alone now, each in their own world. If they went too slow they’d lose, too fast and they’d die. Within moments they would be engaged in a solitary pursuit of the sweet spot drivers called the limit.

THE LIMIT

Phil Hill after the 1950 Pebble Beach Cup, the last-to-first dash that converted him from mechanic to driver. (Pebble Beach Company)

1

An Air of Truth

PHIL HILL HATED THE DINNERS most of all. The vile dinners with his parents cursing each other across the long table in their Santa Monica dining room. Shouting, taunting, springing from their chairs and spilling wine. Hill sat in stony silence with his siblings, too shaken to touch the pot roast or fried chicken put in front of them. Even as their parents fought, the children were required to maintain perfect table manners.

It always happened the same way. In the afternoon Hill would hear the faint chime of piano keys, the major and minor chords chasing each other as his mother worked out arrangements for the hymns she composed for publication. At 5 p.m. sharp his father left his job as postmaster general of Santa Monica and drove to the Uplifters Club, a hard-drinking enclave of civic stalwarts and businessmen, where he was known for making extemporaneous political speeches over a series of whiskeys. After more drinks—sometimes a lot more—he headed home in a darkening mood.

Julia, the black cook, climbed the tiled stairs of their home on the edge of Santa Monica to tell Hill and his younger brother Jerry and sister Helen that they would eat with the grown-ups that night. They dreaded it. Their father was a devoted Roosevelt Democrat, their mother an avid Republican. Meals ended in political quarrels enflamed by booze. Later Hill would sleep with his hands covering his ears to muffle the screaming downstairs.

When Hill was fourteen his father came home drunk and hit his mother. Hill pushed between them and hit him back. “It was the first time I ever struck my father,” he said. “I had this feeling of power over him, finally. I remember it was a good feeling.”

It should have been an ideal childhood. The Hills were pillars of Santa Monica, a thriving community on the edge of Los Angeles with a palm-shaded promenade overlooking a broad beach where children swam and played ball in the California sunshine. They lived in a Spanish-style house on 20th Street with creamy stucco walls, exposed beams, and dark wood floors. Shirley Temple lived next door. It was the picture of California comfort.

The setting was no solace to Hill. He grew up wretchedly disconnected from his domineering parents and painfully unsure how to fit in to his surroundings. He was slightly built and sickly, and he stood aloof from the boys patrolling the neighborhood. When polio broke out in 1936, his mother hired a tutor to homeschool Hill and his siblings for a year. He was further confined by a sinus condition that required a tube inserted in his nose. He was too clumsy to find escape in sports. “I was awful,” he said. “When we played baseball I was always the poorest member of the team—the fact that I was cursed each time I came to bat didn’t help me play any better.” His only contentment was playing the piano. It was not just the music that captivated him, but also the reliable mechanical play of key, hammer, and damper.

His mother was too preoccupied with her own musical pursuits to pay much attention to family. She stayed up late listening to an Edison Victrola and writing hymns, including a popular song called “Jesus Is the Sweetest Name I Know.” She also wrote religious tracts refuting the claim that Prohibition had a biblical basis. By her reading of the Bible, God endorsed drinking. And drink she did. In the mornings she slept it off while a chauffeur delivered Hill and his brother to school. “Jerry and I hated to let the other kids see us,” he said. “This was during the Depression, and we felt just awful being taken to school like a couple of royal princes, complete with Buster Brown haircuts.”

Hill’s father, Philip Toll Hill Sr., was a disciplinarian with the rigid mindset of a lifelong civil servant. He came from a long line of stalwart northeastern burghers and businessmen, all of whom attended Union College in Schenectady, New York. He followed in their path, then became a navy lieutenant in World War I and city editor of the Schenectady Gazette before taking a sales job with Mack Truck in Miami, where he married Lela Long, a farm girl from Marion, Ohio, with musical ambitions.

Philip T. Hill Jr., was born on April 20, 1927. Four months later the family fled Miami as a hurricane bore down. Lela had lived through one hurricane, and she refused to face another. The family drove across the country to Los Angeles, where Hill’s father briefly worked as foreman of the L.A. Grand Jury, then became postmaster general of Santa Monica.

He was a remote figure who ruled the household with regimentation. His children addressed him as “sir.” He trained his sons to greet women with a bow and a crisp click of the heels. In 1935, he sent eight-year-old Hill to the Hollywood Military Academy. “Be a good little soldier,” his father told him. Hill was anything but soldierly. His one interest was the most unmilitary activity available: playing alto horn in the school band.

Hill found his salvation in the family garage. The story of his childhood is bright with automotive impressions—the elegant tangle of wires under the hood of his mother’s shiny Marmon Speedster; the Oldsmobile a family friend let him drive around the block, his back supported by pillows and his feet grazing the pedals; the 1928 Packard his parents drove up the coast road to Oxnard for picnics, with Hill egging his father on. “I remember going down one of those hills seeing 80 on the speedometer,” he said. “And stuff was blowing out of the car and my mother was screaming bloody murder—and I loved it.”

When Hill and some friends were driven home from a birthday party in a green 1933 Chevrolet sedan, he paid each passenger twenty-five cents for the privilege of sitting beside the driver and shifting gears. They laughed at his determination as they held out their tiny palms to collect the coins. “I was born a car nut,” he said. “Really a mental case.”

It was common for boys to fall for the full-figured cars of that era, but Hill verged on infatuation. Staring out at San Vicente Boulevard, he would challenge neighborhood boys to shout out the make and year of approaching cars faster than he did—’39 Chrysler Royal, ’40 Chevy Coupe, ’23 Dodge. They rarely beat him. He could spot a hundred models dating back to the 1910s. “It was as if I was trying to divorce myself from the presence of the people around me,” he said, “and focus myself only on the cars.”

The only adult who encouraged Hill was his aunt, Helen Grasselli, a wealthy Cleveland socialite. After divorcing her husband, a successful chemical manufacturer, she came west and settled in a house down the block from her sister. Helen had no children of her own, so she doted on her niece and nephews, buying them gifts and taking them on vacations in Miami. She favored Phil in particular, in part because she shared his fascination with cars. She let him sit on her lap and handle the oversized wooden steering wheel of her Pierce-Arrow LeBaron Convertible Town Cabriolet as they cruised empty canyon roads. It was a car of stately luxury with an outdoor seat for chauffeurs and a wood-lined passenger cabin furnished with a lamb’s wool rug and a beaverskin lap robe. “Phil was in awe of that car,” said George Hearst Jr., grandson of William Randolph Hearst and a classmate of Hill’s at the Hollywood Military Academy. “We all were.”

Before the development of automatic transmissions and power steering, driving was an act of physical athleticism. Climbing the Sepulveda Pass through the Santa Monica Mountains one day, Helen grew impatient as Louis, the chauffeur, ground through a ponderous series of ill-timed gearshifts. She shoved him aside and took the wheel. When Hill was twelve, he and Helen spotted a black Model T Ford in a used car lot while walking down Figueroa Street in downtown Los Angeles. “It had only 8,000 miles on it and everything was original,” he later said, “but they wanted an outlandish price for it—$40.” His aunt bought it for him and arranged for its delivery that evening. “I peeled back the curtains and there it was, shuddering back and forth in the street below, with that familiar whine of the planetary box, and unmistakable sound in low and reverse,” he said. “The salesman told me, ‘Now, you get low by pushing the left-hand pedal down, high by letting it out. The middle pedal is for reverse and the throttle is on the right side of the steering column. Have you got that, boy?’ ”

Hill’s father disapproved, and he ordered his son to stay off public roads. Fortunately for Hill, his friend George Hearst Jr. owned a slightly later version, the Model A. The boys drove the private roads of the Hearst estate in Santa Monica Canyon, and they staged races on a quarter-mile horse track on the property, skidding their way around the dirt oval.

“I learned a hell of a lot about the dynamics of cornering from that old Model T,” Hill said. Even then he knew how to pull back from the edge of recklessness. “I was enthralled with cars and power and speed, but I already had a certain saving caution. I did not, for example, ‘bicycle’ that Model T—in other words, corner it on two wheels, as some characters I knew often did with their cars.”

Hill learned how to handle the Ford, and he learned how to fix it. When the connecting rod for the pistons or crankshaft broke, Louis the chauffeur showed him how to replace it. While the neighborhood kids played baseball, he roamed junkyards looking for bargain cylinder blocks and carburetors. He could not stop his parents’ drinking and fighting, but he could mend a busted throttle. Just as the children of Narnia slipped an oppressive home by stepping through the wardrobe, Hill found enchantment under the hood. He absorbed himself in the intricate language of carburetor, clutch, camshaft, and cylinder heads. He had found an escape to an ordered and predictable world where every pedal and piston had a clear purpose and responded to his touch.

“I’ve always expressed myself via the automobile,” he said. “I guess I sensed that I was in an insane environment and that my only escape was in something that had structure. Cars gave me a sense of worth. I could do something—drive—no one else my age could do. I could take cars apart, too, and when I put the nuts and bolts back together again and the thing worked, no one could prove me wrong. That kind of technology was fathomable, made sense in a way people never did. Cars are easy to master; they hold no threat; and, if you’re careful, they can’t hurt you like people can.”

Pooling money from his allowance and a part-time job pumping gas, he bought a succession of cars, including a 1926 Chevy and a 1940 Packard convertible. He acquired them at a time when teenage boys, particularly Californians, expressed disdain for the fake chrome styling of Detroit by turning showroom models into hot rods, “hopping them up” with rebuilt transmissions, lightened flywheels, extra carburetors, superchargers, and half a dozen coats of shining lacquer. It was a subversive creativity, as graffiti and hip-hop would be to later generations. The kid who once breathed through a tube and could barely swing a Louisville Slugger had found his gift. He tested his handiwork on San Fernando Road and the side streets of Santa Monica, which in the 1940s were relatively empty and unpatrolled by police.

Teenagers met at stoplights and squealed away in clouds of smoke, their chrome exhaust pipes amplifying the throaty roar. “There was no problem in finding out whether a driver who pulled up beside me wanted to drag,” Hill said. “We had our little signals. If one guy revved his engine in a subtle way, and that was returned, then the drag would be on. My left foot would be trembling on the clutch in anticipation as I waited for the moment when I let it in and took off.”

Leadfooters and throttle stompers met at the Piccadilly drive-in on Sepulveda Boulevard or Fosters Freeze malt shop in Inglewood to eye each other’s hop-ups and talk to girls. Hill was shy, but handsome in the manner of California hot rodders, with a ripple of dark hair and muscled hands stained with grease. Gas rationing had ended, and Hill and his friends chased each other on coast roads and twisty canyon drives. The wind blew their hair. Girls laughed in the backseat.

On weekends he drove a hundred miles over the mountains to the flat expanse of dry lakebeds near Muroc and El Mirage, where teens and war veterans congregated beyond the reach of police. They rolled into the desert in the evening, their headlights winding through the mesquite and sagebrush, and gathered around bonfires with beer and bedrolls. They started their engines at dawn, before the sun warmed the flats.

The Southern California aircraft industry had produced a generation of young men adept at welding and lathe work. From their garages and backyards came a fleet of lowered and lightened hot rods—fenderless, hoodless, and roofless. They were uncomfortable but fast, skimming the hard-packed sand at 125 mph and kicking up thirty-foot rooster tails of chalky dust.

One by one, or in pairs, they peeled across the desert, reaching speeds as high as 125 mph or so before hitting what they called “the traps.” A stopwatch triggered when they crossed a rubber hose and stopped when they hit a second hose a quarter mile away. Timers seated at a makeshift table calculated their speed and shouted it to onlookers standing by in the hot rod uniform of Sinatra-slick pompadours and flapping shirttails.

Hill stacked issues of Autocar, Motor Sport, and other British magazines in his bedroom. At night he studied the grainy photographs of his faraway heroes—Juan Manuel Fangio, Luigi Villoresi, Alberto Ascari—leaning into curves on dusty Sicilian hills or rampaging down Adriatic straights. The images were like dispatches from a foreign war, their drama magnified by remoteness.

Hill had never seen specimens of that world up close until a boy named Donny Parkinson started showing up on the lakebeds in a Bugatti or BMW. Parkinson’s father was a prominent architect—he designed the Los Angeles Coliseum and City Hall—and a prodigious car collector. Parkinson, who would later marry Hill’s sister, invited Hill to borrow from the family’s automotive library, and to inspect their considerable stable of foreign cars. Hill passed his hands over the Italian leather seats and German steering wheels without much hope of ever seeing that world firsthand.

In fact, his future was altogether unclear. His friends Richie Ginther and George Hearst were drafted in advance of the Korean War, but the military rejected Hill because of his sinus condition. So he worked for a while on the opposite end of the war, as a nose-gun assembler at the Douglas Aircraft plant in Santa Monica. His father wanted him to attend Union College, but Hill defied him by enrolling at the University of Southern California where he halfheartedly studied business administration, a subject Helen urged because she expected him to someday handle her estate.

He joined Kappa Sigma fraternity, attended sorority parties, played folk songs on a guitar, and cruised fraternity row in Helen’s Pierce-Arrow. He did everything expected of a pledge, but his heart was not in it. Try as he might, he could not summon his father’s gusto for hobnobbing and backslapping. Even after moving into the frat house he would slip away a few nights a week to stay in the bedroom he kept at Helen’s house. He had long since abandoned his parents’ home.

Hill called his college career “a bust.” He was a lackluster student and an indifferent frat brother, but he could not come up with an alternative. In the late 1940s California was bursting with opportunities, but he was adrift. “From the time I was a little boy, people would ask me: ‘What do you want to be, Phil?’ I couldn’t tell them,” he said. It didn’t help that his brother Jerry was the classic California boy—blond, self-assured, athletic, and popular with girls.

Hill listened hard for a calling, but heard only pistons. Car mechanics was the one subject that stirred him, but grease monkey did not seem a plausible occupation. Mechanics were dropouts. It was considered a job of last resort.

Nonetheless, Hill jumped when a job presented itself. In June 1947, after Hill’s second year of college, Hearst referred him to a mechanic named Rudy Sumpter who needed help in the pit crew of a midget car owned by Marvin Edwards, a manufacturer of automotive springs. Hill abruptly left school and began working for Sumpter. “My parents were apprehensive,” he said, “but they didn’t seem to get through to me.”

From the college quadrangle to the midget pits: It’s hard to imagine a more radical change of scene. The midgets were stumpy little scaled-down cars built strictly for racing and usually sponsored by garages and gas stations. They were high-powered but relatively light, no more than 850 pounds, which made them entertainingly dangerous. Hill had a close-up view as the cars skidded around dirt tracks in a movable scrum, thumping off each other and smacking the fence—all the while kicking dirt into the grandstands and belching cumulus clouds of blue smoke. The drivers sat upright, exposed to flying clumps of hard sod. They pulled into the pits with fractures, burns, busted noses, and cracked teeth.

Midget racing played to beery blue-collar crowds. It was a cross between demolition derby and NASCAR—an ugly distant cousin of the European road racing Hill revered. During the warm-up laps at Gilmore Stadium in West Hollywood, an 18,000-seat arena built specifically for midget racing, a designated bad guy named Dominic “Pee Wee” Distarce (“Mussolini’s gift to midget racing”) gave fans the finger. A jolly chorus of boos rained down. Vendors hawked beer and peanuts. The air was filled with exhaust plumes and a cinderous odor.

A rousing former pilot named Gib Lilly drove the Edwards midget. He raced twice a week, at the Rose Bowl on Tuesdays and the Orange Show Speedway on Thursdays, consistently finishing near the top. In the grimy midget demimonde, he was a hero. Hill was a junior mechanic, known as a “stooge,” but he learned how to keep a car in winning form. He worked in the pits, a half-covered concrete command post stinking of Castrol oil and stocked with spare tires and tools laid out like an operating theater. When Lilly pulled in, Hill went to work—refueling, repairing, banging off worn tires and wrestling on fresh ones. “I was just a mechanic’s helper, but I had an identity,” he said. “I had a real label which I could hang onto at last.”

Not long after Hill began working for Sumpter, Hearst asked him to pick up his new car. Hill drove down Wilshire Boulevard to the dealership and saw Hearst’s MG-TC, a small, boxy British two-seat roadster, parked at the curb. The MG was a favorite of GIs stationed in England, and it touched off a sports car fad when they began bringing them home at the end of the war. The MG was flashy and fast—effortlessly reaching 70 mph on empty roads. It looked like a car Cary Grant might drive.

In the 1940s European sports cars were so rare that American owners honked and waved to one another. Hill had seen MGs in magazines, but this was his first intimate look at its round tachometer mounted on a curvy walnut-veneer dashboard, red leather upholstery, swoopy fenders, carpets, and wire wheels. “I could see so much classic beauty in that car,” he said.

After inspecting the MG, Hill sold his Ford, borrowed money from his aunt and assorted friends, and bought his own MG for a little more than $2,000 from International Motors, a dealership next to Grauman’s Chinese Theater on Sunset Boulevard. It was his first taste of European engineering, a revelation of handling and lively pickup. By comparison “the typical American car of the day was a wallowing pig. The sports car had—how should I put it?—an air of truth about it.”

Hill was working at the midget tracks two nights a week, but he now added a day job as a mechanic and salesman at International Motors, which sold MGs, Jaguars, and Mercedes to business leaders and movie stars. Their customers included Humphrey Bogart, Clark Gable, and Gary Cooper. He shared the showroom with Bernard Cahier, the son of a French general and a member of the Resistance who had enrolled at UCLA and married a sorority girl. Cahier’s gravelly French accent gave him a big advantage, particularly selling the two MG models, TCs and TDs, that were popular with American women. “You wanna Tissy or a Tiddy?” was his standard opening line.

Compared to the flamboyant Cahier, Hill was an unexceptional salesman, in part because of his unhinged enthusiasm for esoteric mechanical matters. “I’d stop to talk at length about cars and certain drivers and about the advantage of one kind of suspension over another with almost every customer who came in the place,” he said.

His jittery, overkeen manner might have vexed the management if Hill had not soon distinguished himself as a driver. In January 1948 he drove his MG in his first real competition, a rally at Palos Verdes, where he finished just behind his boss, an established amateur driver named Louis Van Dyke.

In 1949 a mix of foreign cars—MGs, BMWs, Morris Minors, Simcas, Fiats, and Austins—began racing on a half-mile paved oval called the Carrell Speedway in Gardena. Hill cleaned up. “Attendance was heavy for a while,” he said. “People came out for the comical aspect, to see those funny little wire-wheeled cars being stuffed into the fences. I avoided the fences and on a good night I could earn $400 to $500.”

California sports car culture was evolving fast and Hill moved with it. He traded his MG for a newer model with rounder lines and a stiffer, sturdier suspension (the same model that James Dean bought a few years later after earning a part in East of Eden). He hopped it up with tricks learned in the dirty midget pits: he installed a supercharger and modified the powerplant, lowered the compression ratio and used larger inlet valves. He knew that worn tires got better traction with more air pressure, and he figured out how to adjust the leaf springs to keep pressure on the inside rear wheel. He finished it off with a red-and-black paint job with white stripes along the doors.

“Certain guys had the touch, and Phil was one of them,” said John Lamm, a friend of Hill’s and a columnist for Road & Track. “He knew how to get that something extra out of an engine. It’s an instinct.”

When there was no official race Hill and his friends organized their own illicit rallies. As the sun set over the Pacific, half a dozen would meet at Saugus, twenty miles north of the San Fernando Valley, and take off down dark canyon roads at one-minute intervals. They considered it safer at night because headlights alerted them to oncoming cars. They called their fifty-mile loop the Cento Miglia in imitation of the Mille Miglia, a thousand-mile road race in Italy. Afterwards they bragged and joked and drank beer at a roadhouse restaurant.

With the MG’s windshield folded flat, the breeze whipped over the long hood, ruffling Hill’s dark hair and tearing his eyes. He felt as if he shared a nervous system with the car. He knew its moods and how to spur it on by dancing lightly on clutch and brake.

Hill still considered himself a misfit, an incorrigible car wonk, but he was unknowingly in tune with a restless undercurrent. Like many Americans coming of age between the atomic bomb and the Beatles, he turned to acceleration as an antidote to restive estrangement. “I mean, man, whither goest thou?” Jack Kerouac would write in On the Road a few years later. “Whither goest thou, America, in thy shiny car in the night?” Like the Kerouac hero Dean Moriarty, Hill was alive to the road without much thought of where it might lead.

Hill began dating a receptionist from International Motors. After work they drove his MG to Hollywood or San Bernardino for the twilight midget races. She sat in the stands eating hot dogs and talking with friends while he repaired midgets down in the pits. “I loved those days,” Hill later recalled. “I don’t really know why except that it was such a simple life. I was totally devoted to it and totally interested in it.”

The midget team was now racing seven nights a week. When a driver broke his leg, Sumpter asked Hill to replace him in a field of forty cars. He spun badly on the first lap of a qualifying race, then settled down as he got the hang of sliding around the dirt oval. The trick was to ride in what drivers called the groove, a line that cuts low on turns and wide on straightaways. He qualified for the finals “even though they told me I looked like a cow walking across an icy pond.”

Hill drove well enough to earn a regular spot, though the assignment soured when he performed poorly in a stretch of races, finishing in the back of the pack at Gilmore Stadium and smacking the fence at San Bernardino. Hill blamed his washout on poor mechanics. Sumpter disagreed. Hill quit.

Midget racing was a uniquely American sport taken up by tough young men from blue-collar neighborhoods. The fastest advanced up the ranks to the Indianapolis 500, the pinnacle of American driving. Hill might have followed that path, but he found oval racing a deadening merry-go-round. California had not yet built an extensive network of roads. Its racing was consequently modeled on horse tracks. Cars skidded counterclockwise around the same quarter mile lap after lap, their wheels perpetually swung leftward. European races, by contrast, were run on a car’s natural surroundings—long loops of closed-off public roads with a rich variety of rises and dips, twists and hairpins. As sports cars grew in popularity, the divide deepened. Hill’s friends from the midget ranks dismissed European sports car drivers as effete “tea baggers.” The tea baggers, in turn, mocked the midget drivers as “circle burners.”

Hill was more connoisseur than combatant. He far preferred the continental aesthetics of speed—the contours of a tapered car body, a finely calibrated engine working its way up the gears like musical scales, a coupe braking at just the right moment as it swung through a curve shaded by overhanging trees.

From his greasy perch in the repair shop of International Motors, he could imagine no happier future than tuning and repairing European cars. With that ambition in mind, he persuaded Van Dyke to send him abroad to study mechanics with the great British carmakers. In the late fall of 1949 he traveled by freighter from Boston to Southampton, England, and then by train to Leamington Spa, a short drive from the Jaguar plant. Hill was met at the train station by a man with the implausible name of Lofty England, who as team manager would lead Jaguar to five victories at Le Mans.

Hill spent a cold winter in a series of boardinghouses while he performed monthlong apprenticeships at Jaguar, SU Carburetors, Rolls-Royce, and MG. It was a harsh change from Santa Monica. In 1949 England was still scraping by on rations. Hill ate mutton and drank lukewarm beer with a coarse-talking crew of Cockney mechanics. “He found himself in this stunningly shabby and war-battered country where seagulls were coughing into the fog and people went about their business looking pale and broken,” said Doug Nye, author of more than fifty books on motor racing. “It was as different from California as a place could be.”

While training at Rolls-Royce, Hill stayed in a drafty Kew hostelry where guests deposited sixpence into an electric radiator for twenty minutes of heat. On his first night he noticed that one of the two heating coils was disconnected, so he screwed it back on. The next night he found that the landlady had disconnected it again. “Every day was this ritual of reattaching it before bed,” he said, “and detaching it in the morning so [the landlady] wouldn’t start augmenting my room rent.”

His intimate encounters with sports car history made up for the rude accommodations. The monthlong training sessions were like a master class, and they allowed him to bask in greatness. He was photographed behind the wheel of “Old Number One,” the first MG ever produced, and he met Goldie Gardner, an elaborately mustachioed old driver who held twenty-two international speed records. In May, toward the end of his stay, Hill rented a room on a farm in Billingshurst, south of London. Spring had come to West Sussex, and the countryside glowed emerald green. The fields carried the rich scent of springtime. That month may have been the only time that Hill enjoyed a peace of the spirit. “During that final month down there, before I headed home, I swore that I would never let myself get tense or nervous again,” he said. “The area had an Old World calm that settled into your bones. I’d roam the hills, walking the country, which was really beautiful at that time of year—and nothing seemed important enough to worry over.”

Hill broke from his respite long enough to attend the British Grand Prix held on a former World War II bomber base at Silverstone, Northamptonshire. It was a far grander event than he had ever seen, with 100,000 spectators in their Sunday best eating sandwiches in white canvas food tents and drinking pints served from forest-green beer trucks. It was the first race attended by a British monarch. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth shook hands with all twenty-six drivers, then retired to the royal box.

From his grandstand seat Hill could see the paddock, an enclosed area beside the racetrack where drivers, managers, reporters, and mechanics mingled among trailers and refreshment tents. The cigar-shaped single-seat Maseratis, Talbots, and Alfa Romeos rolled to the starting line and barked to life. They rumbled nose-to-tail around the flat 3.6-mile course marked by hay bales, flashing by the grandstand with a thumping vibration that Hill could feel in his sternum. He could not imagine that he would ever drive in such an event.

Seventy laps later the Italian anthem played in honor of the winner, an impassive Italian named Nino Farina who sang as he raced. Like the drivers of the 1930s, he wore no helmet, only leather goggles pulled over a linen aviator’s cap. He was among the first to strike a casual posture behind the wheel—arms outstretched at ten and two o’clock, head cocked to the side—that would be widely adopted by Hill’s generation. Farina would go on to win the 1950 championship, the first held after the war and the first governed by a new set of specifications for cars and engines known as Formula 1. It was considered the fastest, most advanced class of racing.

Hill returned to the United States in June with a souvenir, a long-hooded black Jaguar XK120 with an open cockpit, red leather upholstery, and rakish windscreen—a gleaming trophy of postwar modernity. The efficient sweep of its lines captured what speed looked like in 1950. Hill made it even faster by drilling holes in the alloy chassis for lightness and replacing the heavy leather upholstery with airplane seats.

During the war Jaguar had been limited to production of military motorbikes and armored sidecars while quietly refining the XK120’s engineering on paper. It was unable to produce the car until 1949. In May 1950, the roadster clocked 136 mph on a straight run along a Belgian highway, making it the fastest production car in existence. It was a sensation: within a year it would be driven by Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Clark Gable, and Lauren Bacall. The MG roadster that had seemed so advanced a year earlier now looked outmoded.

Hill’s Jaguar came with a plaque bolted to the dashboard certifying that it was a replica of the record-breaking model. It was packed in the hold when Hill arrived in New York on the Queen Mary. He disembarked on a West Side pier, drove over the George Washington Bridge, and motored 2,440 miles to California, stopping en route to see the Indianapolis 500. Before the construction of interstate highways, cross-country drives threaded through small towns. One can only imagine the reaction when the black Jaguar stormed by at 30 miles over the speed limit.

At twenty-three, Hill had no designs on greatness. “The limit of my ambition,” he said, “was someday to become mechanic to a great racing driver.” That would change soon enough.

On November 5, 1950, five months after returning from England, Hill waited in the fifth row of bulbous sports cars—Allards, MGs, a Frazer Nash—pushed into position at a makeshift starting line beside a horse corral. Earlier he had snuck into the woods to heave a hearty vomit, as he often did before racing. He inhaled deeply and rested his hands on the steering wheel. It was the biggest race of his life.