Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

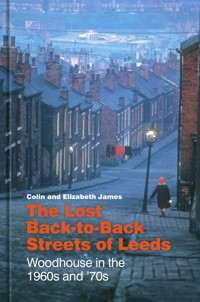

Despite what journalists chose to highlight, the gas lamps in Woodhouse still had work to do because the streets were not empty of life. Some houses were boarded up but many – often next door – were still family homes, albeit in the last years of occupation. Shops were still open, the washing lines swung in the wind across the streets where the children were playing, the cats and dogs sunbathed on doorsteps. They were a fertile source for photographs. In the 1960s and 1970s the suburbs of Woodhouse were undergoing a sweeping transformation from groups of back-to-back terraces to late-twentieth century houses amid green spaces. Chronicling this period of change was a student with a camera. The Lost Back-to-Back Streets of Leeds tells the story of Woodhouse's shifting urban landscape through pictures and the meticulous research behind them. At their heart are not just houses and shops, but also the people who lived or worked in them in a time of such great change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 96

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Colin & Elizabeth James, 2024

The right of Colin & Elizabeth James to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 515 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword by Dr Joanne Harrison

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Back-to-Back Houses of Leeds and Why They Started to Disappear

Chapter 2: Exploring ‘Great’ Woodhouse and its History

Chapter 3: Little Woodhouse and Burley

Chapter 4: Bringing the Streets to Life

Chapter 5: Shops, Shopping and Economic Changes

Chapter 6: The Changing Landscape in the 1970s

Chapter 7: The ‘Woodhouse (Rider Road) Clearance Area’ and a Reprieve for Some Householders

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Notes

Colin James has been an active photographer since he acquired his first camera at the age of 12. He began taking photographs in Leeds as a student at the University studying for a food science MSc, (1967-69). His career was spent in the food industry and latterly in school but his first love is photography and he rarely leaves home in King’s Lynn without a camera! Some of his pictures have appeared in magazines and other publications, plus requests from local organisations for event pictures to be submitted to the local press.

Elizabeth James read Latin at the University of Leeds (1967-70) and also holds an MA in local and regional history from the University of East Anglia (1991). She is a retired administrator of King’s Lynn Minster, and formerly a curator of the Lynn Museum. Her first love is local buildings and heritage but whatever she studies is rooted in the lives of the people at the heart of it. Alongside working on Leeds with Colin, she collaborated with a friend on a book publishing over seventy songs collected in Lynn by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1905, for which she researched the lives of the individual local singers.

Foreword

I was really pleased to have been recommended by Leeds Civic Trust to write the foreword for this book. As I found out during the course of my MA and PhD research on back-to-back houses in the Harehills neighbourhood of Leeds, my twenty-year connection with the houses is not a long one – I met some residents and former residents whose family had lived in a single house for around eighty years. I only lived in mine for five, but there was something about them that fascinated me, and I’ve spent the last ten years doing the same things as Colin and Elizabeth have in producing this book – trekking the streets with my camera and survey forms, trawling through archives, and trying to piece together the architectural and social history. There is a lot of interest throughout Leeds in the back-to-back houses, demonstrated not just to me as a researcher, but to Leeds Library and Leeds Museums, who have reported on the popularity of my guest blogs and exhibitions. But interest is wider than that, evidenced by the success of my academic articles and my TV appearance on Great British Railway Journeys.

In Harehills, developed from 1888, most of the streets are still extant, but I led a community project in 2021 that was a spin-off of my main research. Entitled ‘Rediscovering the lost streets of Victorian Burmantofts and Sheepscar’, I couldn’t help smiling when I saw the title of this book. These two neighbourhoods comprised predominantly Victorian terraced houses, but the houses and most of the streets were lost to so-called slum clearance. The designs, and I expect also the social history of these earlier houses, have much in common with those in Woodhouse featured in this book.

The importance of the history and heritage captured in this book cannot be overstated. The houses and shops may be lost on the ground, they may be lost in the memories of younger generations, and they may not even be known to newcomers, but now we have a comprehensive collection of photographs that can be passed on and remembered. What is also of significance in this work is that the period of the photography was one of rapid transition between the Victorian and Edwardian way of life and the modernity that we now have.

My own research indicated that despite the back-to-backs having more sophisticated facilities than similar-sized houses in other towns at the turn of the twentieth century, they did not change much at all until the government-initiated improvement programmes of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. Colin and Elizabeth report much the same in Woodhouse.

Another important insight, again replicated in the Harehills research, is the way in which residents of back-to-back houses complied with the same social norms as their counterparts in small through terraces, for example by washing clothes in the kitchen and hanging it on a line to dry. It seems obvious enough, but adaptations were made to achieve this, most notably, hanging washing across the street rather than in a back yard.

Colin and Elizabeth are astute in their selection of quotes and their observations, showing the many facets of a declining neighbourhood and the concerns of residents awaiting relocation prior to demolition of their houses. These themes are evident in other research too; not just in Leeds’s twentieth-century history, but more recently in Liverpool’s Welsh Streets, where residents suffered at the hands of the government’s Housing Market Renewal Programme, aka ‘Pathfinder’.

The final chapter ensures that this is not just another local history book. Moving into discussion of architectural conservation and separating cosmetic or service deficiencies from the structural integrity and heritage value of the houses, it adds to the growing literature on the relevance of older working-class housing for twenty-first-century living and the value it brings to our neighbourhoods.

This book will undoubtedly be of interest to current and former residents of Leeds, but also to historians, architects, planners and policy-makers throughout the UK who may look to it to fill a void in knowledge so they can learn from the past and develop their own work. Working in all of these fields, it is a book I shall keep close at hand.

Dr Joanne Harrison

Introduction

Books about local history based on old photographs are often a collection from several sources, but not this one. These pictures were taken in the 1960s and ’70s, by one photographer, who is joint-author of this book. His fellow author has written the text, and we believe that the photographs have become an archive of an important period in the changing Leeds suburban landscape. Our book’s aim is to share a selection of the pictures; it is our contribution to the records of the city where we met, while we were students at the University of Leeds.

Colin arrived from London and I from Norwich in the autumn of 1967. We found Leeds a very interesting city, full of friendly people but undergoing rapid changes. During that term my mother sent me a four-page feature on Leeds, dated 13 November 1967, from the Daily Mirror’s ‘Boom Cities!’ series.1 Full of enthusiasm for change, progress and explosive economy, it highlighted the sweeping redevelopment of city centre buildings and suburban housing alike. The university, embarking on its own wave of major rebuilding, was described as ‘a hotch-potch of ancient villas, stone blocks and holes in the ground’. That was sweeping journalism; we also had the venerable Waterhouse buildings in University Road and the lofty white Parkinson clocktower, reminding students of lecture times and regulating the neighbours’ timepieces. But the Mirror feature also referred to back-to-back terraced housing, empty in expectation of the arrival of new houses, where ‘cobbled streets sprout grass, corner shops are shuttered. A gas lamp lights no footsteps.’

Colin was and is a keen photographer and he brought his cameras to his new home on campus. Just across Woodhouse Lane (the A660) he discovered the streets of back-to-back terraced housing. Despite what journalists chose to highlight, the gas lamps in Woodhouse still had work to do because the streets were not empty of life. Some houses were boarded up but many – often next door – were still family homes, albeit in the last years of occupation. Shops were still open, the washing lines swung in the wind across the streets where the children were playing, the cats and dogs sunbathed on doorsteps. They were a fertile source for Colin’s photographs because there was nothing like them back home.

Publishing a selection of the pictures was the result of a chance suggestion by friends, who saw them as an archive to be shared with a wider audience. To help us select pictures and identify the right narrative theme for them we had two vital resources: the detailed photographic lists Colin had maintained at the time and the survival of our 1960s street atlas of Leeds. So many streets had vanished: their successors often perpetuate the venerable names of their predecessors, but they do not always follow the same layout on the ground. We loitered on street corners looking puzzled, map in hand, sometimes approached by helpful passers-by who thought we might be lost!

Much supporting research was needed for the text; we now live in Norfolk but it was a good excuse for repeated, if sporadic, visits to Leeds to carry it out. We needed to explore the rise of Victorian and Edwardian housing in Woodhouse and even to find out why the houses were built that way in the first place. Whose were the names above the shops? What did the residents think about the great 1960s clearance and rebuilding and where they would be living next? What was said to them about why it was thought necessary? Come to that, who decided it was necessary and why?

We received very generous help to find the answers from people who sometimes went the extra mile in doing so and they are named with gratitude in the formal acknowledgements. At such a distance we still do not feel qualified to write an exhaustive account of how one area of the city among many went through such a transformation; our narrative focuses on the story as told by the pictures themselves.

In addition to Woodhouse itself, Colin also took interesting pictures of the terraces just above Burley Road, technically part of ‘Little Woodhouse’, and at Burley itself, which it seemed a shame not to include. We have also included some well-chosen present-day photographs to provide clarity, add extra information and help to show good things that came out of the redevelopment: pleasant houses and wide green recreational spaces where there were none before.

All buildings are shaped by the needs, whether or not well-met, of the people who have lived or worked in them. People appear in many of these photographs because a good photographer knows that they bring a picture to life. The November 1967 Daily Mirror