Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

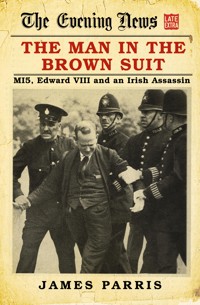

On 16 July 1936 a man in a brown suit stepped from the crowd on London's Constitution Hill and pointed a loaded revolver at King Edward VIII as he rode past. The monarch was moments from death. But MI5 and the Metropolitan Police Special Branch had known for three months an attack was planned: the man in the brown suit himself had warned them. This mysterious man, lost to history, was George McMahon, a petty criminal with a record of involvement with the police. He was also an MI5 informant, providing intelligence on Italian and possibly German espionage in Britain. Dismissed by the rest of the world as a drunken loser and fantasist, he saw his life as an epic drama. Why did MI5 and the police fail to act? Was it a simple blunder on the part of the security services, or was something far more sinister involved? In this first full-length study of the threat to the life of Edward VIII, James Parris uses material from MI5 and police files at the National Archives to reach explosive conclusions about the British Establishment's determination to remove Edward from the throne.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE MAN IN THE BROWN SUIT

MI5, Edward VIII and an Irish Assassin

THE MAN IN THE BROWN SUIT

MI5, Edward VIII and an Irish Assassin

JAMES PARRIS

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© James Parris, 2019

The right of James Parris to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9355 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Prologue

I Two Men: Edward and George

II Prelude to Assassination

III ‘The Dastardly Attempt’

IV McMahon’s Trials

V Afterlives

VI Bungling or Collusion?

Select Bibliography

Notes

Prologue

‘Thou shalt not kill; but needst not strive

Officiously to keep alive.’1

At 12.30 p.m. on 16 July 1936, as the massed bands of the Brigade of Guards had passed and King Edward VIII was following on horseback, a limping man in a shabby brown three-piece suit pressed his way through the crowd lining the pavement along Constitution Hill and drew a loaded revolver from his pocket. Edward was a few yards and seconds from death. In a flurry of panic and confusion, the gun left the man’s hand, skidding across the road, coming to rest between the hind legs of the king’s horse. The Annual Register for 1936 recorded that this ‘alarming incident created a momentary panic throughout the country’.2

The man with the gun was George Andrew Campbell McMahon, a 32-year-old Irishman. At his Old Bailey trial in September he was dismissed by the Attorney General Sir Donald Somervell as an attention-seeking eccentric acting in pursuit of a petty grievance against the police. Pronounced guilty by the jury of unlawfully and wilfully producing a pistol with intent to alarm the king, McMahon was sentenced to twelve months in prison with hard labour.

So far, so simple.

But MI5, the British security service, had been aware since April 1936 that there was a plot to assassinate Edward: McMahon himself had told them. He informed an MI5 officer with whom he was in regular contact that the attack was planned for June or July and that he was involved. He had even shown the agent the revolver he said he always carried. Interviewed by Special Branch, McMahon told the same story. When McMahon met his MI5 handler on 13 July he named the day and place that the attempt would be made. MI5’s chief, Sir Vernon Kell, discussed the threat with the Metropolitan Police assistant commissioner, Norman Kendal.

Despite knowing what was coming – where, when, how – MI5 and Special Branch did nothing: they neither placed McMahon under close observation nor tailed him as he set out from home on 16 July carrying a .36 calibre revolver loaded with four bullets, with more ammunition in his pocket. McMahon had the nerve to ask a mounted policeman to shift out of his line of vision and took the gun from his pocket, yards from the king. Why were MI5 and Special Branch paralysed? Crass bungling, or was something more sinister involved? Were they intentionally standing aside, allowing an attempt on the king’s life to proceed?

Edward had no doubt that the threat to his life had been real, masking his concern with an attempt at a joke. His courage in the circumstances was admirable. ‘We have to thank the Almighty for two things,’ he later wrote to the general who had been accompanying him on horseback from the ceremony in Hyde Park. ‘Firstly, that it did not rain, and secondly that the man in the brown suit’s gun did not go off!!’3 The king’s mistress and future wife Wallis Simpson wrote after the incident, ‘The shot at HM and the upset summer plans have all been very disturbing … No place seems very safe for kings.’4

Assassination was certainly in the European air. On 6 May 1932 Paul Gorguloff, a Russian refugee from the 1917 revolution, fired three pistol shots at the French president, Paul Doumer, at the opening of a Paris book fair. Two bullets hit the 75-year-old Doumer, one in the right armpit, the other his head. He died in a hospital bed the following day. Gorguloff, a convicted abortionist, had been angered by what he saw as the French government’s weak attitude towards Communists. In court Gorguloff’s lawyer claimed his client was insane, a plea the jury rejected. Gorguloff was condemned to death and despatched by guillotine on 14 September.

Two years later, on 25 July 1934, a squad of Austrian Nazis gunned down Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss in a failed coup attempt. The plotters were tried and hanged. Not long after, on 9 October, King Alexander I of Yugoslavia was shot, along with his chauffeur and the French foreign minister, Louis Barthou, while driving through the streets of Marseilles at the opening of a state visit. Both the king and the minister died. The assassin, Vlado Chernozemski, a Bulgarian separatist, was slashed by a cavalry sabre, trampled by the crowd and shot by a police officer, dying the same evening.

In 1929 the French writer André Breton proposed in his Second Manifesto of Surrealism: ‘The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistols in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.’5 Breton intended no such thing and this display of intellectual terrorism was merely an attempt to shock the bourgeoisie. By coincidence, an International Surrealist Exhibition opened in London in the summer of 1936, with Breton – the ‘Pope of Surrealism’ – a dominating presence. The exhibition catalogue claimed for the movement: ‘It is defiant – the desperate act of men too profoundly convinced of the rottenness of our civilisation to want to save a shred of its respectability.’6

A few weeks later, McMahon stood on Constitution Hill brandishing a loaded revolver. Cold and efficient, the weapon – even in the hands of an inexperienced gunman – was capable of unleashing five bullets in two seconds. His exploit appeared as senseless as Breton’s projected acte gratuit, an empty gesture. When he came to trial, the prosecution seemed determined to convince an Old Bailey jury that this was indeed the case, minimising the deadly implications of McMahon’s action. The essential difference was that he carried a real weapon, with real bullets, in the presence of a living king.

Was McMahon acting out his own surreal fantasy, or had MI5 and Special Branch allowed or perhaps even colluded in something far graver and far more disturbing? There were many in the political establishment and in the royal family itself who had long believed Edward was not fit to be king, even that he represented a danger to national security.

King Edward VIII did not die as some may have wished in the summer of 1936. The problem of removing an unsuitable monarch found its resolution a few months later with Edward’s self-inflicted social death, his act of abdication. He and Wallis Simpson – the twice-wed and twice-divorced ‘woman I love’ – went into exile, married and measured out the decades that followed in an idle faux-aristocratic charade as the ‘Duke and Duchess of Windsor’.

His conversations often began, ‘When I was king …’ The couple’s associates were seedy, moneyed Americans, minor European nobility of dubious provenance, and – with an all-too-apt irony – their near neighbours the fascist Mosleys, Oswald and Diana. The duke died in 1972, aged 77, followed fourteen years later by his widow. But Edward had faced the possibility of his actual demise, his physical death, much earlier, while the forces of law and order stood by with arms folded.

I

Two Men: Edward and George

1

At first glance, the contrast between the two men whose paths crossed so dramatically on Constitution Hill on 16 July 1936 – Edward Windsor and George McMahon – could not have been greater: the invisible man emerging from the crowd to confront the all-too-visible man, history from below clashing with history from above. But what they had in common would have surprised them. Both were estranged from their families, having broken painfully and irrevocably. Both had brothers who outshone them in managing the business of everyday life. Both took pains with their appearance, anxious to present a stylish image to the world. Both flirted with the politics of the right. Above all, both sought to escape the constricted and unsatisfying existences to which they felt themselves condemned. Their shared unwillingness to accept the parts birth intended them to play made them, despite the vastly different arenas in which they performed, companions in subversion.

2

Unlike the ever-obscure George McMahon, every fact is known about Edward Windsor, every detail set out, scrutinised, analysed, fictionalised. A glance each morning at the Court Circular in The Times, Daily Telegraph or Morning Post in the 1920s or ’30s would tell the reader where Edward had been and was due to go, though not what he was thinking. Blessed, or cursed, with a sensitivity that heightened an awareness of his position, Edward recognised early on the essential emptiness of the public role to which he was destined. A fellow European royal, Victor Emmanuel III of Italy, had been advised by his father Umberto, ‘Remember: to be a king, all you need to know is how to sign your name, read a newspaper, and mount a horse.’ Victor Emmanuel, like Edward, eventually abandoned his throne. At the age of 25 the Prince of Wales bemoaned to his private secretary, ‘Christ, how I loathe my job now and the press “puffed” empty “succés”. I feel I am through with it and long to die.’1

Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David Saxe-Coburg und Gotha was born on 23 June 1894 at White Lodge, Richmond, the first son of the Duke and Duchess of York. Four names – George, Andrew, Patrick, David – were intended to represent in his person the unity of the nations making up the kingdom. The Independent Labour Party Member of Parliament for West Ham South, Keir Hardie, outraged the House of Commons a few days after the birth by telling them, presciently:

From his childhood onward this lord will be surrounded by sycophants and flatterers by the score (Cries of ‘Oh, oh!’) and will be taught to believe himself as of a superior creation. (Renewed cries of ‘Oh, oh!’) A line will be drawn between him and the people whom he might be called upon some day to reign over. In due course, following the precedent which has already been set, he will be sent on a tour round the world, and probably rumours of a morganatic alliance follow (Loud cries of ‘Oh, oh!’ and ‘Order!’ and ‘Question’), and the end of it all will be that the country will be called upon to pay the bill.2

Half a century later Edward, now Duke of Windsor, would write of Hardie that, ‘as a prophet of Royal destiny he has proved uncannily clairvoyant.’3

The roll of the child’s godparents at his christening in July showed the wide reach of the family’s European network, a Monarchic International: Queen Victoria (great-grandmother), King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Denmark (great grandparents), the Prince and Princess of Wales (grandparents), the Duke and Duchess of Teck (grandparents), the Duke of Cambridge (grand-uncle), the Duke of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha (grand-uncle), Queen Olga of Greece (grand-aunt), Prince Adolphus of Teck (uncle), the Tsarevitch Nicholas of Russia (father’s cousin), and King William II of Württemberg (mother’s cousin).

Within two decades many of the titles had gone, the emperors, kings and nobles banished, leaving Britain one of the few countries maintaining the institution of monarchy. Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, left to the mercy of the Bolsheviks by his fearful cousin George V (Edward’s father), was driven from the throne in 1917 and then a year later executed, wife and children perishing with him in a Yekaterinburg cellar. All the German princes and dukes lost their crowns in 1918, and Kaiser Wilhelm, another of George’s cousins, scuttled off to exile in the Netherlands as his country went down to defeat and revolution. In total, five emperors, eight kings and eighteen minor dynasties were stripped of their crowns during George V’s reign.

How long would the British monarchy survive? Even before the First World War Edward’s grandfather, Edward VII, was bleakly pessimistic about the Crown’s prospects, as the former Grand Duke Alexander of Russia recalled in 1932:

I shall never forget the reconciled irony of Edward VII’s voice when, as he sat on the terrace of his summer palace and looking at his then very youthful grandson, the present Prince of Wales, playing in the garden below, he nudged me and said with the air of an astrologist reading the future: ‘You see that boy – the last King of England!’4

In 1917 Edward’s family began adjusting to what already promised to be a new and, for them, alarming state of affairs. In February cousin Nicky had been toppled from the Russian throne. In July, with no end in sight to the war and the embarrassing paradox of the Saxe-Coburg und Gotha clan leading the nation against the Hohenzollern house in Germany impossible to ignore (particularly when Gotha bombers appeared over London), the royal family adopted a fresh, more English guise. Summoned by the king to Buckingham Palace on his appointment as prime minister in December 1916, the relatively lowly born David Lloyd George had asked, ‘I wonder what my little German friend has got to say to me?’ Older members of the family had been so at ease with their Teutonic roots, Edward recalled in later life, that they relaxed into German once the English servants were safely out of the room.5

‘We,’ George proclaimed on 17 July 1917, ‘having taken into consideration the Name and Title of Our Royal House and Family, have determined henceforth Our House and Family shall be styled and known as the House and Family of Windsor.’ Hearing the news, the German Kaiser – Queen Victoria’s grandson, Edward’s first cousin removed – laughed and said he was off to the theatre to see a performance of Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. The household of one of Edward’s cousins and future close friend Louis made the equally hasty transition from Battenberg to Mountbatten.

As well as undergoing this change of surname at the age of 23, Edward would pass through a succession of titles: Prince Edward, Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay; Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester; King and Emperor of India; finally coming to rest as Duke of Windsor. To family and close friends he was David, not Edward. His early formation had all the casualness of preparation for an insubstantial, if not inconsequential, life: a man born to what he had no choice but to become. Reared with the emotional neglect common to the contemporary upper classes, tormented physically and psychologically by his nanny, Edward was barely educated by a private tutor chosen for sporting rather than academic ability. ‘He never taught us anything at all,’ Edward recalled to a friend half a century on, adding in an almost word-for-word echo of something George McMahon would say, ‘I am completely self-educated.’6

Edward often complained in later life that he had felt unloved as a child. ‘I had a wretched childhood,’ he was quoted as saying. ‘Of course, there were short periods of happiness but I remember it chiefly for the miserableness I had to keep to myself.’7 Whether George V actually made the terrible promise, ‘My father was frightened of his mother; I was frightened of my father, and I am damned well going to make sure that my children are frightened of me,’ and it is disputed, he certainly gave the impression this was the child-rearing philosophy he felt happiest with. A family acquaintance once remarked that Edward’s father enjoyed setting ambushes for his children on trivial points of etiquette or dress so he could then berate and humiliate them, his booming voice taking a sarcastic edge. The outcome for his sons was hardly surprising: Edward, a fashion-obsessed playboy with an inability to concentrate; Albert (Duke of York, later George VI), who suffered from a stutter, a ferocious temper, lifelong gastric problems and an obsession with uniforms; George (Duke of Kent), a sexually ambivalent drug addict.

When Edward’s emotionally inhibited mother, Queen Mary, died in 1953 he observed to his wife, ‘I somehow feel that the fluids in her veins must always have been as icy cold as they are now in death.’8 The Liberal Chancellor of the Exchequer Lloyd George, who organised Edward’s investiture as Prince of Wales in 1911, underlined this feeling about Queen Mary’s distance from her son, telling his private secretary, ‘She was always against the little fellow.’9 Mary herself was once heard describing Edward as ‘my poor silly son’.10 As if this sense of a dearth of affection were not enough, Edward had little contact with children of his own age, playtime confined to his brothers and carefully selected companions.

In 1907 Edward followed in his father’s steps as a cadet at Osborne, the naval college on the Isle of Wight, despite failing the entrance exam. This was a necessary emblematic move in a Britain that ‘ruled the waves’. Tearful on arrival, he was the only boy never to have been away from home before. Asked his name – an obvious provocation, as no one could be in doubt – he replied, ‘Edward’. ‘Edward what?’ – ‘Just Edward, that is all.’ Shy and small for his age, he was stamped with the nickname ‘Sardine’. Thrust into the company of thirty strangers in a dormitory, Edward was bullied and given a reminder one afternoon that England had executed a monarch. A group of cadets seized him, raised a sash window, slowly lowered the frame until he was held by the neck, and ran off. This symbolic acting out of the axe that had decapitated Charles Stuart, and of the French revolutionary guillotine, continued until the boy’s cries brought release.

The Royal Naval College at Dartmouth was the next destination for a young man intended for a career as a sea-going officer. Edward went on to Dartmouth in 1909 but it soon became obvious that a naval life was out of the question and that his future would be purely ceremonial. On the death of Edward VII in May 1910 and his father George’s accession to the throne, Edward became heir, taking the title Duke of Cornwall and the duchy’s revenues of £90,000 a year, largely held in trust until he reached 21. His grandfather’s funeral at the end of the month represented the last unified parade of European monarchy, with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, the kings of Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Greece, Norway, Belgium and Bulgaria, together with representatives of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria, Tsar Nicholas of Russia and the King of Italy.

A year later, on his sixteenth birthday, Edward was invested as the nineteenth Prince of Wales at Caernarfon Castle in an ‘invention of tradition’ ceremony mocked up by Lloyd George – Constable of the Castle, as well as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He primed the prince with a few rudimentary Welsh phrases. Against a background of suffragette ‘outrages’, bitter class war in Britain’s industrial areas, and intensifying strife over Irish home rule, Edward and his family were called upon – not for the last time – to provide a colourful diversion from reality.

At the conclusion of his course at Dartmouth, Edward went briefly to sea, spending three months as midshipman on the battleship HMS Hindustan, never leaving British waters, hardly more than a lengthy cruise. Nevertheless, it was the taste of a career Edward might have enjoyed had he been free to choose. A letter from the ship’s captain to Queen Mary praised her son’s zeal. But George called Edward to Sandringham, the family home, and told him he would have to leave the navy, which he said was ‘too specialised’ an activity for the heir to the throne. The adult Edward understood all too well the irony of his pretend life, joking that though he was now entitled to wear an admiral’s uniform he pitied anyone having to rely on his navigational ability.

The pattern of Edward’s existence now seemed determined – shifting from one activity to another, with no opportunity to focus or concentrate on an occupation or endeavour that might satisfy him. In October 1912, after spending four months in France with the Marquis de Breteuil to develop his French, Edward registered as an undergraduate at Magdalen College, Oxford. His stay at the university had originally been intended to last for one year, but he stayed for two. Though accompanied by an equerry, his childhood tutor and a valet, Edward enjoyed greater freedom than he had previously known, living and mixing with a wider range of men – though obviously still within a narrow class band – hunting, playing tennis, golf and polo, turning out for the college football 2nd XI, and parading with the Officers’ Training Corps. He was also celebrated for annoying his neighbours with incessant strumming of the ukulele. Naturally, he was elected to the Bullingdon, the socially exclusive dining club, but was forced to resign by his mother, Queen Mary, when she had reports of a particularly raucous evening.

Edward took little if any interest in what Oxford had to offer academically. His tutors cobbled together a special course in history and modern languages, but there was never any intention he should take a degree. He passed the Easter and summer vacations in the palaces of a string of his German relations. Kaiser Wilhelm, with whom Edward stayed in Berlin, described him as ‘A most charming, unassuming young man … a young eagle, likely to play a big part in European affairs because he is far from being a pacifist’.11 Edward later wrote of how the Germany he knew at this time impressed him. ‘I admired the industry, the perseverance, the discipline, the thoroughness, and the love of the Fatherland so typical of the German people, qualities that were to be found in every calling …’12

Wealthy and with no encouragement to take up interests that could in any way be described as cultural or intellectual – ‘Bookish he will never be,’ his Oxford tutor blurted out to The Times in 1914 – Edward became devoted to fashion. This was understandable given that the role to which he was born involved turning up at the right place at the right time in the right outfit. Appearance was everything. For Edward as Prince of Wales and as king the cut and pattern of trousers (from Foster & Son) and jackets (from Frederick Scholte of Savile Row) took on an absolute importance. He single-handedly created a new vogue by defying his father and wearing brown shoes with a navy blue suit. In later life he described himself, with no hint of irony, as a ‘true British dandy’. In 1934, as Prince of Wales, Edward could claim to have been the first man in England to replace the conventional button fly in trousers with the zip, a move followed by his brother, the Duke of York, and his cousin Lord Louis ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten.

George V had developed the solid and unostentatious respectability of a country squire during his reign, marking out the contrast with his own father, the rakish Edward VII. George’s son, whose manner of life would make him increasingly vain, selfish and extravagant, found this a difficult part to play. ‘We have come to regard the Crown as the head of our morality,’ Walter Bagehot had written in The English Constitution in the reign of Edward’s great-grandmother, Victoria. George understood that; Edward could not or preferred not to. The danger for Edward lay in continuing to play the eternal pretty youth, slim, slight and irresponsible, into adulthood. In 1916 Lord Edward Cecil would describe to his wife how the 21-year-old prince had struck him: ‘He is a nice boy of fifteen, rather immature for that age … I hope he will grow up, but he is leaving it till late.’13

Two decades later Wallis Simpson, the double divorcée Edward abandoned his throne and country to marry, called him ‘Peter Pan’ when writing to a previous husband, in what had been a long-standing private joke between them. As Peter says in J.M. Barrie’s play, ‘I just want always to be a little boy and have fun.’14

3

Two days after Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Edward was commissioned and drafted into the 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards. His first hope had been to rejoin the navy, where he had trained to be an officer. His pleas in October to be allowed to accompany his regiment to the battlefront in France were rejected. He told the War Secretary, Lord Kitchener, that with four brothers in line to replace him as heir to the throne his death would hardly be a disaster. Kitchener’s response was that he was less concerned with Edward being killed than with the possibility of his being taken prisoner. To Edward’s disappointment he was transferred to the 3rd Grenadier Battalion at Wellington Barracks and then attached to the staff of the commander-in-chief, Sir John French. A general promised the king in November he would keep his son well occupied and as far from gunfire as possible.

Edward was deployed on morale-boosting visits to the armies in France, generating what appeared to be a genuine and long-lasting affection for him among the troops who, despite the extra bull and cleaning his appearances demanded, perhaps instinctively recognised – albeit from a distance – his genuine and sympathetic humanity. But he complained to a family friend in March 1915, seven months into the war, ‘I hold commissions in both services and yet I’m not allowed to fight. Of course, I haven’t got a proper job, which is very painful to me and I feel I am left too much in a glass case.’15

In Autumn 1915 Edward conducted a tour of inspection of the front line with the Guards Division commander, the Earl of Cavan, during a lull in the Battle of Loos. Waves of men had advanced earlier across open ground towards enemy trenches and many of Edward’s Grenadier comrades were lying where German machine guns had cut them down. This was his first real encounter with the carnage of battle. As he returned to the royal Daimler with Cavan the area came under shell fire, forcing them to take shelter. When the bombardment ceased and they emerged into the open, Edward found his car riddled with shrapnel, his driver killed. He wrote in his diary, ‘I can’t yet realise that it has happened!! … This push is a failure … I have seen & learnt a lot about war today.’ The impact of all this remained in his mind and he was to write thirty years later, ‘The battle of Loos was one of the great military fiascos of the war.’16

Edward was distressed by his recognition of the essentially make-believe nature of his role. He slept comfortably in chateaux in France, never in a trench or dug-out under shell fire, plagued by rats and the ever-present fear of death. He was to write bitterly forty years later, ‘It took me a long time to become reconciled to the policy of keeping me away from the front line. Manifestly I was being kept, so to speak, on ice, against the day that death should claim my father.’17 His frequent periods of leave in London and the frustration of his position encouraged a taste for drinking and lounging in nightclubs he was never to lose.

In the June 1916 King’s Birthday Honours list Edward was awarded the Military Cross. The medal had been instituted in 1914 as a decoration for officers carrying out ‘acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy’. He was aware of the contempt fighting troops felt for staff officers sporting decorations intended to commend acts of exceptional bravery. He tried to reject the award, just as he had earlier attempted to decline the presentation of the Croix de Guerre from France and the Order of St George from Russia. Edward wrote to his father, ‘I think you know how distasteful it is for me to wear these two war decorations having never done any fighting & having always been kept well out of danger!!’ He continued, ‘I feel ashamed to wear medals which I only have because of my position …’18 His father ordered him to have the medal ribbons sewn onto his uniform tunic at once. Edward went on to protest at the absurdity of his promotion from lieutenant to captain when he held no position of command over troops and was never likely to.

The pressure of war was teaching Edward a lesson about the nature of monarchy. What he saw as undeserved medals and unmerited promotion symbolised an existence he found humiliating: never really a sailor, a student, a fighting soldier or an officer with responsibility for the lives and welfare of his men; always the pretender. Edward’s war continued uneventfully with six weeks in Egypt, ostensibly inspecting and reporting on transport and supply organisation in the Canal Zone, but mainly devoted to visiting Australian and New Zealand troops recently withdrawn from the Dardanelles debacle, and sightseeing along the Nile. He interrupted his journey home to pass a few days near the front against the Austrians with Victor Emmanuel of Italy, whose father had tutored him in the minimal demands made on kings; he returned to France in September 1918, attached to the Canadian army staff until the Armistice ended the war in November.

In 1919 Edward described his wartime experience to a City of London audience: ‘The part I played was, I fear, a very insignificant one, but from one point of view I shall never regret my periods of service overseas. In those four years I mixed with men. In those four years I found my manhood.’19 This was an honest, if touchingly immature, estimation of the part he had played. But a manufactured myth that Edward had endured the danger and squalor of the trenches was encouraged to take root in the popular imagination. The Times once described King Edward as ‘a soldier proven in war’.20 The fascist William Joyce – who as ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ would go on to broadcast Nazi propaganda from Berlin in the Second World War – exaggerated even more in an article praising Edward, describing him as ‘a soldier, who possesses actual fighting experience’.21

Edward would surely have shown himself to be as brave and dogged as the millions of men in every army thrown into battle as volunteers or conscripts. As a steeplechase rider in the 1920s his nerve would border on the reckless. But fate denied him the chance to test himself under fire. Though he certainly suffered the distress of hearing that friends and army comrades had been killed, Edward did not experience the trauma of their dying beside him. On 1 April 1918, as the German Spring Offensive on the Western Front was breaking through the Allied lines, he wrote to his new mistress Freda Dudley Ward: ‘How kind fate is to have sent me back to Italy, so that I am escaping that fearful battle!! It’s very unpatriotic of me to say this but still these are my genuine feelings …’22 It was only to Freda that he could reveal these kinds of emotions and thoughts.

An official photograph of Edward taken shortly after the war shows him dressed as the recently appointed colonel-in-chief of the Welsh Guards, a lavish display of medal ribbons over his left breast pocket, three lines in all, not a single one earned under fire, much to his regret. There is another side to this, a spontaneous display of immense compassion. Following the Armistice in November 1918 Edward visited a Belgian military hospital and was taken to a ward where twenty-eight horrifically wounded men were being cared for. He greeted and exchanged a few words with twenty-seven and then asked where the final man was:

They explained that this case was too ghastly a wreck of humanity. He was no more than a breathing lump of ruined flesh. None knew even his nationality. The Prince demanded to see him, and against what was left of that face he put his cheek.23

The war had given Edward a ringside seat at the fracturing of the old order throughout Europe. It was inconceivable that, as for many of his generation, this would not have an impact on his attitude to life and his response to what the world expected of him.

4

At Buckingham Palace, Edward’s post-war role as Prince of Wales was already being mapped out behind his back. As early as April 1917 – when Tsar Nicholas had lately been deposed by his subjects and the word ‘revolution’ was beginning to ring out across Europe – the Bishop of Chelmsford, John Watts-Ditchfield, suggested to the king’s private secretary, Lord Stamfordham, that ‘the stability of the Throne would be strengthened if the Prince of Wales married an English lady,’ adding that she must be ‘intelligent and above all full of sympathy’.24 After the embarrassment of a war fought out by the subjects of inter-married royal cousins, making the farcical name change from Saxe-Coburg und Gotha to Windsor an urgent necessity, the future monarchy must be fully English, with no European influences there to provoke awkward questions about the meaning of ‘patriotism’. The Daily Express, though, thought it might be an idea for Edward to marry an American.

A new face of monarchy was being prepared, one that left the palaces and showed itself to the public. One, in Stamfordham’s words, that demonstrated that the Crown was ‘a living power for good’.25 An early signal was the appointment in 1918 of a full-time Buckingham Palace press officer. Next, there were plans to deploy royal patronage of charities and voluntary social services to make the monarchy appear relevant to people’s everyday lives. An occasional wave from the fairy-tale coach was no longer seen as enough. This would, the feeling was, justify the institution’s continuing existence at a time when, as Lloyd George put it at the London Guildhall the day the war ended, ‘Emperors and Kingdoms and Kings and Crowns are falling like withered leaves before a gale.’26

The part Edward personally was to play was outlined in October 1918 by Clifford Woodward, soon to be appointed as the king’s chaplain and future Canon of Westminster Abbey. He recommended to the influential Stamfordham that in view of the Labour Party’s growing strength, and the threat of a levelling revolution, the Prince of Wales should engage himself with social problems to consolidate working-class loyalty to the Crown. ‘It would, I suppose, be far easier for him than for the King and it might lead to very big results.’ Woodward submitted that Edward night even set up home for a time in one of Britain’s major industrial centres.27

Edward was never forced to make that always-unlikely move to the provinces, but his parents and their advisers encouraged him to present himself over the next decade or so as ‘the people’s friend’ to further the Windsor survival strategy. A deferential and compliant media – the press, the cinema newsreel corporations and BBC radio – bolstered him in this until the very moment of his abdication in 1936. He eventually became patron of over 750 charitable and welfare organisations.

But first came the Empire, as Edward was despatched to reinforce imperial unity, ‘a family of nations bound together’, as The Times was to put it, ‘by the golden link of the Crown’. It had, of course, been Queen Victoria’s assumption of the title ‘Empress of India’ in 1876 that re-injected popular enthusiasm into a faltering monarchy. A parallel role was to drum up trade for British goods – one newspaper described him as the ‘Empire’s star salesman’. Edward’s next few years were taken up with a run of visits to Britain’s overseas possessions, confirming the forecast Keir Hardie had made in 1894. From August to November 1919 Edward toured Canada (also taking in the United States), cheered by rapturous crowds, eulogised by the press in every city as a royal for the modern age (as every young royal invariably is), descending into the multitude to bestow the princely touch. When the prince’s arrival in Basutoland (now Lesotho) coincided with the end of a long drought, he was eulogised for his supposed supernatural powers.

In almost daily letters to his mistress Freda Dudley Ward, the estranged wife of a Liberal MP sixteen years her senior, Edward revealed the self-doubt and sense of entrapment plaguing him behind the smiling mask. A month into the tour he complained about the pressure of maintaining the ‘P. of W. stunt’ and doubted his fitness for kingship. ‘I feel I am through, & realise as I have so often told you sweetheart that I’m not ½ big enough man to take on what I consider is about the biggest job in the world.’ Two weeks later he complained, ‘I feel like a caged animal.’28

When he came to write his autobiography A King’s Story after the Second World War Edward described what his father had said to him in 1918, and would often repeat: ‘Remember your position and who you are – in the years that were to come that injunction was to be dinned into my ears many, many times. But who exactly was I?’29 Edward knew the crowds flocking to greet him did not see an individual, a man, but a walking symbol. ‘I am not so foolish as to think that the wonderful welcome given me in Canada and again today are mere tributes to myself,’ he said on his return to England from North America. ‘I realise that they are given to me as the King’s son and heir.’30

What followed from this for Edward was whether he could feel confident anyone at all would like, love, admire or respect him for the person he was rather than the title he carried, or, as he had said, whether they saw only the fiction the press created. Every prince is handsome, every princess is beautiful, every king dutiful and wise. The prison in which he believed himself trapped could drive him to an agony of despair and self-loathing. In a Christmas 1919 letter to his private secretary, Edward wrote, ‘No one else must know how I feel about my life, and everything … I do feel such a bloody little shit.’31

Edward felt no enthusiasm for what he described to Freda as the ‘next fucking trip’, to Australia and New Zealand in 1920. His companion – cousin, and at the time his closest friend, ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten – calculated that the 210-day round of charming strangers, delivering speeches and dancing with smitten women ate up 45,000 miles, taking in 208 cities and towns. Being in such intimate confinement for such a length of time gave Mountbatten insight into Edward’s moods. He wrote to his mother, ‘At times he gets so depressed, and says he’d give anything to change places with me.’32

In one letter to Freda during the long Pacific crossing Edward wrote that he longed to marry her, that he could marry no other woman, but that it would be cruel to ask her to take on the job of wife to the Prince of Wales. ‘It just would not be fair on you sweetheart though who knows how much longer this monarchy stunt is going to last or how much longer I’ll be P. of W.’33

In March 1920 the anguished prince confessed, ‘I’m not strong by nature & so have to rely on other people for help in my work & have to be bolstered up though I know it’s silly and unnecessary; if only I had some guts.’34 Two years later his mood had not altered: ‘What I wouldn’t give to chuck this P. of W. job. I’m so fed up with it you know & don’t fit in.’35 He was a man trapped, self-destructive, self-pitying, already desperate to cast off the role he was born to, sixteen years before his eventual abdication. Freda recalled a fraught conversation in which Edward asked why he could not live an ordinary life. ‘You were born to be king,’ she told him,

It’s there waiting for you, and you can’t escape it.

Again and again I heard him grumble, ‘What does it take to be a good king? You must be a figurehead, a wooden man! Do nothing to upset the Prime Minister or the Court or the Archbishop of Canterbury! Show yourself to the people! Mind your manners! Go to church! What modern man wants that sort of life?’36

The years 1921 and 1922 found Edward representing his father the king-emperor in India, Ceylon and Malaya. India he felt was the most dispiriting destination of all. The tour of these imperial possessions came not long after the Amritsar massacre, when Indian troops under British command killed over 300 unarmed civilians protesting peacefully against the deportation of two nationalist leaders. The atmosphere was bitter. Edward had tried to persuade Prime Minister Lloyd George to talk the king into sending his younger brother Albert instead.

Despite his self-image as ‘progressive’ and a ‘democrat’ to whom the experience of army life had given the common touch, Edward seemed to have no comprehension of the widespread resentment Indians had towards alien British rule. He was critical of even the most limited moves towards self-government, denouncing them as ‘pandering to the natives’. As Edward’s official biographer tactfully put it, ‘He had no doubt that the Indians and Burmese were wholly incompetent to run their own affairs and would be lost without the benevolent supervision of their colonial masters.’37

Agitation by Mahatma Gandhi and the pro-independence Congress Party ensured, despite mass arrests of activists, that the crowds greeting Edward were meagre compared to those he had grown accustomed to in North America and Australia. Security was tight as plans were uncovered to bomb Edward’s party. He wrote to his father on 16 December 1921, ‘Well I must tell you that I’m very depressed about my work in British India as I don’t feel I am doing a scrap of good; in fact I can say that I am not.’38

Edward boasted in his autobiography, A King’s Story, that he was a rebel, scorning the outdated values of his father’s generation, and in some minor ways he was and did. But one value he did share was their deeply rooted sense of white superiority, a prejudice he was to maintain all his life and took no trouble to hide from his peers. He wrote to Freda from Barbados in March 1920, ‘I didn’t take much to the coloured population, who are revolting.’ In July he wrote excitedly from Australia:

Oh, I forgot to tell you that they showed us some of the native aborigines … they are the most revolting form of living creatures I’ve ever seen!! They are the lowest known form of human beings & are the nearest thing to monkeys I’ve ever seen … these filthy nauseating creatures …39

Stopping briefly in Mexico during the cruise home from Australia and New Zealand, Edward gave Freda his impression of the town of Acapulco. ‘The people are too revolting for words, sweetheart,’ he wrote, ‘super dagoes & some of them are quite black as a result of Spaniards inter-breeding with the Indians; & of course they only talk Spanish so that i couldn’t make myself understood even in my bad Italian …’40

5

Edward’s expeditions to Britain’s industrial and mining areas through the 1920s followed a similar pattern to his Empire tours and were undertaken for similar reasons – an attempt to bind together an economically fragile nation, one still psychologically traumatised by war, through the magic of monarchy. In post-First World War Britain, the fear that discontent could lead to revolution, though exaggerated, remained in the minds of the authorities. Returning from Glasgow, the city of the radical Clydesiders, Edward wrote to Freda, ‘I do feel I’ve been able to do just a little good propaganda up there and given Communism a knock.’41 He would later say in his memoirs, ‘These provincial forays were miniatures of my Imperial tours.’42 The left-wing Labour MP Aneurin Bevan spotted the inference of this de haut en bas attitude on one of Edward’s visits to South Wales, organised, Bevan commented angrily, in ‘much the same way as you might go to the Congo’.43

In July 1922 Edward came closer to danger than he realised when two Irish Republican Army volunteers contrived an audacious plan to kidnap him at the Cowes Regatta. On 22 June two IRA gunmen – both former British soldiers – murdered the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Henry Wilson, outside his London home, firing six bullets into him. Surrounded by a crowd and captured, the men were tried and sentenced to death. A London-born Republican activist, John Carr, persuaded Dublin IRA command that their lives could be saved by taking the Prince of Wales hostage, holding him to force the British authorities into granting a reprieve. Carr and a Republican volunteer named Denis Kelleher made their way to the Isle of Wight, close to the house where Edward was staying with the Barings, the Anglo-German banking family. But when an alert constable began to take an interest in Kelleher’s strong Irish accent the pair were scared off and abandoned the attempt.

It takes only a small leap of the imagination to see the dire possibilities had the Republican exploit gone any further. A bungled attack could have seen Edward shot. Had the kidnapping succeeded, he might have died in a subsequent botched rescue attempt or been murdered by the IRA men out of desperation. Edward would never have become king and the succession would have passed to his younger brother, Albert, the future George VI. The plan itself was patently amateurish and absurd, the work of two not-very-bright pawns in a wider struggle. But the same could have been said of a plot to murder the Chief of the Imperial General Staff in a London street in broad daylight. That had succeeded.

In England, Wales and Scotland, as in Canada, Australia and India, Edward stood before audiences grinding out the platitudinous speeches written by his private secretaries Godfrey Thomas and Alan Lascelles, affecting knowledge and experience he had never achieved.44 The comic Charlie Chaplin performed an impression among friends of Edward addressing a crowd that captured the vulnerability of his style. ‘Chaplin tugged at non-existent cuffs, acknowledged the thunder of the mob, licked a lip and bobbed his head in nervous modesty from side to side: almost a prevision of the melancholy future King.’45

In May 1926 Edward addressed the annual pageant of the Boys’ Brigade in the tone of confident faux-wisdom common to royal speeches. ‘It has been stated, and it most certainly is not exaggerated, that the most important members of the community are the boys, not only for the future of this nation, but for the future of the British Empire.’46 The man who would never spend a moment of his life in productive work or knowingly risk a penny of his unearned wealth in any kind of useful enterprise instructed an audience of hard-headed Birmingham businessmen in January 1927 to visit Canada, where he owned a 4,000-acre dude ranch. ‘Canada and the Canadians are a real tonic. They sharpen one up, and they provide, on the serious side, a widened outlook in business ideas which will compensate for any apparent loss of time in work over here.’47 Edward’s problem was that while he could rustle up a convincing performance, he understood the absurdity of what he was doing only too plainly.

Despite the Bishop of Chelmsford’s hope in 1917 that Edward would eventually marry ‘an English lady’, Edward’s preference for relationships with already married women suggested he was reluctant to adopt the ostensibly settled domestic life the public had been led to expect from the heir to the crown. His father, George, had married at 28, and his grandfather – the philandering Edward VII – even earlier at 21. Edward remained a bachelor when he came to the throne at the age of 41, his lustre already showing signs of fading. ‘I have an inordinate dislike for weddings,’ he wrote to his mother, Queen Mary, in 1922. ‘I always feel so sorry for the couple concerned.’48

Why was he loath to marry? There were rumours, impossible to substantiate, of gay flings with his cousin ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten during their Empire tours together, with his equerry Major Edward ‘Fruity’ Metcalfe, and earlier, at Oxford, with his private tutor Henry Hansell. But Lady Diana Cooper, at the heart of the prince’s circle in the 1920s and 1930s laughed at the idea when it was put to her. ‘Don’t be ridiculous. He was never out of a woman’s legs.’49

In 1916 Edward’s fellow officers had taken him to a brothel in Calais, where he was entertained by some kind of sexual performance. ‘A perfectly filthy and revolting sight, but interesting for me as it was my first insight into these things,’50 he recorded in his diary. His first heterosexual experience was orchestrated in the same year by two Guards officers, who introduced him to a prostitute in Amiens named Paulette. In April 1917 he began an intense liaison lasting some months with an up-market prostitute Marguerite Alibert, four years his senior.

Edward’s next physically and emotionally significant relationship was with Freda, wife of the Liberal MP William Dudley Ward and mother of two daughters. It was to her – as his many letters showed – he could openly express his unhappiness about his role as heir to the throne. The affair was at its most fervid from 1918 to 1923, when Freda cooled, but she remained his closest confidant until the mid-1930s. In the early years, one biographer observes, Edward was ‘madly, passionately, abjectly in love with her’.51 Edward’s affairs, while enthusiastically gossiped about in high society (to the embarrassment and anger of his parents), were kept from the public by an obsequious press absorbed in projecting him as the eternally eligible bachelor.

His final mistress before Wallis Simpson made her appearance, was Thelma, wife of Viscount Furness. From early 1930 Thelma and Edward, whom she called the ‘Little Man’, were regular weekend companions at his home, Fort Belvedere, and at her houses in London and Leicestershire. In January 1931 she introduced Edward to her friend Wallis, unwittingly bringing forward the woman who would turn out to be her replacement.

In one aspect of his life, Edward gave every appearance of feeling comfortable with established practice – Freemasonry – though he makes no mention of this enthusiasm in A King’s Story. As Prince of Wales he restored the convention broken briefly by his father, George V, of members of the royal family joining the ‘Craft’. He was initiated into the Household Brigade Lodge No. 2614 in March 1919 and elected master of the lodge by fellow members in 1921. He was additionally a member of the St Mary Magdalen Lodge No. 1523 (master in 1925), the Lodge of Friendship and Harmony No. 1616 (master in 1935), and the Royal Alpha Lodge, No. 16.

Edward rose through Masonry’s perhaps intentionally comic-sounding hierarchy until in June 1936, five months after succeeding to the throne, he broke his formal connection and took the title ‘past grand master’. Not before, however, exerting his influential position to ease the passage of Wallis Simpson’s husband Ernest into his lodge, angering fellow masons who were convinced that by doing so Edward had broken his masonic oath.

In his private moments, Edward knew that for much of the time he was living a charade, aware how out of kilter he felt in the role to which birth had condemned him. Not only was there the existence that convention expected him to lead, there was the life the people – for all their enjoyment of his apparent informality – had been conditioned to anticipate. ‘How shall I behave here?’ Edward once asked an American as he walked into a Paris club. ‘Like a human being,’ the American replied, just as another English visitor bowed to the prince. Edward sighed, ‘How can I?’52 What could he have become had he been free to follow his inclinations, to find and develop his own talents? He least of all knew. ‘I am a misfit,’ he told his private secretary in 1927.53 George McMahon, despite the gulf in their circumstances, would, if he were being honest, have echoed Edward’s words exactly.

6

Jerome Bannigan, there can be no doubt, was in revolt against the narrowness of the life to which he seemed destined. His brother Patrick, seizing one opportunity open to a bright young Roman Catholic, trained for the priesthood, while another held ‘a fairly responsible position’ in a Clyde shipyard office. Jerome left school at 14 to work as a barboy. In his late twenties he changed his name to George Andrew Campbell McMahon, perhaps hoping that a new identity would open up fresh prospects. He remained in the world’s eyes a loser, thwarted in his aspirations, an unstable drunk, always on the look-out for a financial opportunity, a chronic – though at first hearing plausible – liar. He was even untruthful about his father’s occupation when he came to marry, trying to elevate himself a notch or two up the class hierarchy.

But McMahon was also a complex man, risking his liberty to expose corruption among Metropolitan Police officers, spying on refugees from Fascism and Nazism, consorting with the intelligence agencies of three European powers, and confronting the King-Emperor with a loaded revolver. There was more to him than the ‘ordinary’ man with a petty grievance that the police, press and courts worked in concert to persuade the public he was in 1936.

‘I should think that he is the sort of man who is perpetually thinking out magnificent schemes, but who has very little ability to execute them,’ an MI5 officer would note.54 ‘Since a child I never had a chance,’ McMahon complained in a petition to Edward VIII in February 1936.55 The following year he wrote to Lieutenant Colonel Cecil Bevis, a justice of the peace and regular visitor to Wandsworth Prison who had befriended him, ‘My career has been a varied one in retrospection. I have very little to enthuse over.’56

McMahon sometimes seems a figment of his own imagination. His history is fragmented to the extent that even the vividly dramatic moment in the summer of 1936, at which he was the centre, remains a puzzle. An account of his life has to be weaved together from reports and memoranda in MI5 and police files, from responses his father and friends gave to journalists’ questions, and from the sketches McMahon made of himself in letters, petitions and court testimony, rarely reliable and sometimes contradictory. The expression ‘unreliable narrator’ might have been invented for him. An editorial in The Times wrote him off as a sociological and psychological cliché, though one requiring punishment:

McMahon is evidently part of the economic wreckage of the day, an intellectual and moral weakling broken by unemployment and poverty, nursing his grievances until they become a blind rancour against society … But, however pitiable, such men are dangerous and it is necessary to remove them to a place where they can do no harm.57

There was more to him than a piece of economic wreckage, though he was sometimes that. But if this was all he amounted to he would have lived and died an alcoholic petty criminal in Glasgow, never leaving, never heard of. What was consistent was the way McMahon slid easily into a world of exaggeration and make-believe, one in which everyday reality was fashioned into a shape more closely resembling his dreams. He had, out of context, the contorted sensibility of the spy, the urge to shuffle identities, to contrive situations, to see how far the game could be taken.

When war broke out in 1939 a drifting McMahon wrote to MI5 applying for employment – ludicrously, given his personal history and his recent chequered relationship with the security service, but apparently seriously. ‘I can prove useful if given a chance, and would if given a trial be found tactful and silent.’ An officer commented in disbelief to a colleague, ‘This man is slightly insane. He should not be employed in any confidential capacity.’58 Had McMahon been making a private joke? It was sometimes hard to tell. The head of the Criminal Investigation Department at Scotland Yard was just as dismissive, writing around the same time, ‘Everybody who knows McMahon is satisfied that he is a border line mental case and a born liar.’59 Nobody used the word ‘misfit’, but the implication was always there.

One thing is certain: McMahon perhaps was Jerome Bannigan. Jerome, for Roman Catholics – as the Bannigan family were – is the patron saint of people with ‘difficult personalities’. Why he should have chosen the particular alias George Andrew Campbell McMahon he never explained, though it must have been when he was fleeing Glasgow, the place of his childhood and youth. Five members of a Belfast family named McMahon had been murdered by police in a revenge shooting in 1922, killed for being readily available Catholic victims. McMahon is of ancient Irish origin and Bannigan may have adopted the family’s name as a token of Irish Republican sympathies, but this is conjecture. George, of course, was the name of the man on the British throne when McMahon took on his new identity.

Though he continued to sign himself ‘Jerry’ in letters to his wife and family, and was known as ‘Mac’ to acquaintances (and his MI5 handler) in London, ‘George’ served as a stage name, a nom de plume or nom de guerre. Like the existential hero he imagined himself to be, McMahon strained to throw off the burden of a troubled past, struggling to create fresh identities and opportunities by an act of will.