Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

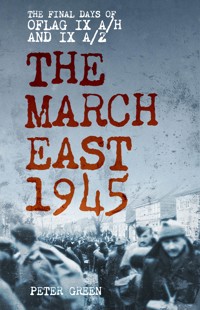

During the final days of the Second World War, for 900 Allied officers held by the Germans, freedom was still a world away. Marched east by their captors, away from the liberating American forces, March and April 1945 was a time of great trials, at the mercy of vengeful Nazis and Allied air raids. Amongst their number were men whose names would become famous post-war, such as actor Desmond Llewellyn, cabinet minister Frederick Corfield and Major Bruce Shand, father of the Duchess of Cornwall. The March East 1945 draws on official and eyewitness accounts, as well as over 30 diaries and memoirs. With more than 120 photographs and exceptional illustrations taken and drawn by PoWs as well as the German instructions for camp evacuation, it reveals the human story that unfolded in Hesse, Thuringia and Saxony, and explains how the prisoners survived until their final liberation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustrations: Front: Captain John McIndoe (Otago Settlers’ Museum, New Zealand); Back: Oflag IX A/Z walk down the main street of Dachrieden, 3 April. (Green Collection)

First published 2012 by Spellmount, an imprint of The History Press

This paperback edition first published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Peter Green, 2012, 2020, 2025

The right of Peter Green to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75247 857 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Timeline

1 Prisoners, Captors and Witnesses

2 Liberation on the Fulda?

3 Eastwards

4 The German Plan B

5 Freedom for Some

6 North then South

7 Unexpected Finale

8 Afterwards

Appendix – People

Sources and Bibliography

Index

About the Author

FOREWORD

Every child has a question of their father – whether that father lived his life to the full or not. My father died when I was 20 months old so I was never able to ask the question. Had he been alive as I grew up I would probably have to ask the question now.

My father would have behaved as a father with me and as someone very different in Oflag IX A/Z. The essence of the person remains however and my very scant memories of him were as a larger-than-life person. All accounts from members of my family who knew him said roughly the same thing.

Through this book I have gained insights as to how his life as a POW may have been. I can imagine him having such a mixture of feelings, from extreme excitement that this Boy’s Own event could be happening to him, to despair that his life might end after many years of captivity, when all he wanted to do was burst with life on the whole world. I don’t think he would have explained it this way, I don’t think he would have been able to explain his feelings. He just did what he did – take photographs – and his excitement is captured in the picture of the jeep moving through Wimmelburg, on 13 April 1945. In contrast, there is the wary relief in the faces of the two concentration camp prisoners; surely he and most of the other POWs would have shared that feeling.

I am sure that all who read this account of the journey in 1945 will gain insights into their fathers who survived something unimaginable. It helps to answer the question – who was my father?

David McLeod Hill, son of Leighton McLeod ‘Lee’ Hill

Pohangina, New Zealand

ANZAC Day 2012

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research for The March East has depended on the cooperation of many individuals and organisations. However the greatest assistance and encouragement has come from Björn Ulf Noll. Björn has unselfishly worked to provide a great deal of information regarding Oflag IX A/Z at Rotenburg and the work of Gunnar Celander. He could always be relied upon to overcome an apparent dead end in the research or open up a new avenue of inquiry; and his personal experiences from living alongside the camp have been beyond price.

The major individual contributors in the UK have been from four participants on the marches: Ernest Edlmann, who made his time available for interviews and provided access to his wartime diary and reports; Michael Langham, who sadly passed away before he could see the results of his contribution; and Robert Montgomery and William Watson, whose memories included insights into the detail of camp life at Oflag IX A/H Upper Camp.

Any reference to the march of Oflag IX A/Z has to include the contribution made by Muriel Roberts, the widow of Harry Roberts. Muriel refused to be thwarted in her efforts to publish her husband’s account of the evacuation, which was one of the starting points for this book. She has very kindly provided access in addition to Harry’s wartime log. Sadly, she passed away as this book went to press.

Jean Beckwith and Gillian Barnard have also been unstinting in their time and in providing access to Ted Beckwith and Rupert Holland material; as has Hugh Wilbraham with regard to his father’s unpublished manuscript.

Björn Ulf Noll’s contribution was in many ways mirrored by Harald Schlanstedt, another witness to events in 1945, who has also unearthed witnesses to the march in its later stages. The other local historians who have made major contribution are Eduard Fritze, Professor Hans Heinz Seyfarth, Thilo Ziegler, Peter Lindner and Fred Dittmann. Horst Ehricht, a family friend, for whom Oberstleutnant Brix was always ‘Uncle Rudolf’ has provided wonderful insights into the life of the Commandant of Oflag IX A/Z.

The contributions of other members of prisoners’ families are very gratefully acknowledged, in particular: Eva Hill, David Hill, Megs Fawkes, Sholto Douglas, Kathleen Biddle, Anthony Foster, James Forbes, Michael Fuller, Thelma McCurchy, John McIndoe, Sheena MacDonald, Simon Mountfort, Sally Phun, Brenda Norris, Alan, Tim and Julie Redway, Sarah Rhodes, Mrs Henrietta Taylor and Grace Westcott. Marion Gerritsen-Teunissen for access to Kenneth Grayston White’s YMCA log and his collection of Lee Hill photographs.

John Irwin, Bob Cardinall and Robert Patton, former members of the United States Army, have helped to explain the ‘Other Side of the Hill’ in a story that is predominantly set in a German context. Ann Sumners has kindly provided access to Charles Sumners’ photographs of US 6th Armored in April 1945.

Ingemar Björklund generously contributed translations of Gunner Celander’s reports to the Swedish Red Cross, whilst Tony Herbert willingly undertook an interview with a camp survivor in Shropshire at very short notice.

The staff of the Otago Settlers Museum, Dunedin, New Zealand, have been extremely generous with their time and in providing access to the John McIndoe material. Other archives, particularly UK’s National Archive, the Imperial War Museum, ITS Internationaler Suchdienst, Riksarkivet and the Bundesarchiv have met all my requests for material with great patience and contributed ideas for further research. Valuable assistance has also been received from the Australian War Memorial, Australian Film Archive, Kings Own Border Regiment Museum and in particular Stuart Eastwood, Maidstone Museum, The New Zealand Film Archive, New Zealand Defence Force Records, Royal Army Chaplain’s Museum, Royal Engineers Museum, The Alexander Turnbull Library, Ushaw College Library, War Art New Zealand and the Zoological Library, Oxford.

Fellow-researchers have contributed via electronic media, but in particular the Feldgrau bulletin board should be singled out for its ability to unearth the more esoteric data about the German Army in 1945.

Finally, I must acknowledge the support of my wife for her contribution and her forbearance in the face of a husband’s obsession with somewhere in Germany in the spring of 1945.

INTRODUCTION

We set off on a march that lasted fifteen days and took us on a zig-zag route across 230 kilometres. It was a march none of us will ever forget.

Lee Hill, ‘Forced March To-Freedom’, Illustrated magazine,12 May 1945

Leighton McLeod ‘Lee’ Hill was a remarkable man. A pioneer of the New Zealand Film industry, he recorded the march east by the Germans of Oflag IX A/Z in 1945 with his camera and diary. His entrepreneurial instincts took over when he sold his photographs and text to the British magazine Illustrated on his return to the UK. The story that appeared under his by-line has some elements of truth but large parts of it are fabrications. We will never know the role that the editorial staff of the magazine played.

What can be said with great certainty is that the article would have played well with its British readers at the time: the German guards were Nazi brutes with whips; it was the evil Germans who shot up Red Cross vehicles; and the prisoners were hostages on their way to the Southern Redoubt. All these stories are contradicted by Lee Hill’s own diary and those of the other participants. The journeys of Oflag IX A/Z and its sister camp Oflag IX A/H do not form part of the canon of Nazi brutality. They were certainly not death marches.

John McIndoe, also a New Zealander, kept a sketchbook during the march and produced images that complement Lee Hill’s photographs. In addition there are over 40 accounts of differing lengths by those who took in the journeys or witnessed them.

Contrary to the expectations of the prisoners, the German commanders were able to keep their prisoners out of the hands of American divisions travelling at many times the speed of the plodding columns. At the same time, the Germans kept the men safe from the rogue elements in the collapsing regime. Nevertheless, for both camps the evacuations became an ordeal that they shared with their guards and the civilians they met at each overnight stop.

This account helps to put the record straight and gives an insight into one small part of Germany’s collapse into chaos in the last weeks of the war.

TIMELINE

22/23 March

Rhine crossings by Allies

27 March

First official warnings that the camps might be evacuated

29 March

Oflag IX A/H walks to Waldkappel, arrives after midnight

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Rockensuß, arrives after midnight

30 March

Oflag IX A/H walks to Wanfried, arrives in the early hours

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Oetmannshausen area

31 March

Oflag IX A/H rest day at Wanfried

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Wanfried, the Kalkhof

1 April

6th Armored cross the Fulda

Oflag IX A/H at Wanfried

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Diedorf

2 April

US 11th Armored reach the Reserve-Lazarett at Obermaßfeld

Oflag IX A/H walks to Lengenfeld unterm Stein

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Lengefeld

3 April

6th Armored cross the Werra

Oflag IX A/H at Lengenfeld unterm Stein

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Windeberg

4 April

Americans reach Mühlhausen and Ohrdruf

6th Armored liberates Oflag IX/AH

Oflag IX A/H at Lengenfeld unterm Stein

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Friedrichsrode

5 April

US Army repatriate the remainder of the patients from Reserve-Lazarett Obermaßfeld

Oflag IX A/H at Eschwege

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Nohra

6 April

Oflag IX A/H at Eschwege

Oflag IX A/Z rest day at Nohra

7 April

German counterattack at Struth

Oflag IX A/H at Eschwege

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Uthleben

8 April

Oflag IX A/H flies to Paris

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Buchholz

9 April

Oflag IX A/H flies to UK

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Uftrungen

10 April

Oflag IX A/Z walks to Dittichenrode

11 April

3rd Armored reach Nordhausen

Oflag IX A/Z by lorry to Wimmelburg, arrive after midnight

12 April

3rd Armored in action with AA guns between Sangerhausen and Wimmelburg

US 9th Army reach the Elbe

Franklin Roosevelt dies

Oflag IX A/Z at Wimmelburg

13 April

3rd Armored reach Wimmelburg

Oflag IX A/Z at Wimmelburg

14 April

Oflag IX A/Z at Wimmelburg

15 April

Oflag IX A/Z at Wimmelburg

16 April

Oflag IX A/Z flies to Liege from Esperstedt

17 April

Oflag IX A/Z at Brussels

18 April

Oflag IX A/Z flies to UK

1

PRISONERS, CAPTORS AND WITNESSES

At last, we rolled into that fateful year 1944 and the invasion of Normandy and then the realisation that the British and Americans were really on the road to the conquest of Germany. Slow as it might seem, we realised at long last that they were coming.

Major ‘Peter’ Brush, Rifle Brigade, captured Calais,May 1940.

In March 1945 the Western Allies had reached the Rhine. Across Germany prisoners of war could finally believe that freedom could not be far off. At Spangenberg and Rotenburg near Kassel, in two camps – Oflags – for British and Commonwealth officers, the inmates had been anticipating release ever since the momentous news had reached them of D-Day in the summer of 1944. Life in the camps was recorded by the prisoners, 45 records discovered in all, some long, some detailed, others very patchy. Those records, including drawings and photographs of the last two weeks of captivity in one of the camps, are amongst the most comprehensive of any camp. They include German, American and Red Cross accounts and show not just the concerns of the men, but also those of the civilians and soldiers in the countryside around them.

The men in the two camps were amongst the most fortunate of the many victims of the Third Reich. Despite the chaos in which they found themselves, German commanders were able, against all probability, to maintain control of their captives and keep them safe from extreme Nazi elements and Allied aircraft. To the prisoners, their experiences from March to mid-April 1945 were evidence of desperate, on occasions random, German attempts to prevent them from being liberated. In fact their captors were acting logically, whilst around them the German Army was fighting on hopelessly and German society was collapsing.

Oflag IX A/H at Spangenberg was an Offizierlager, a camp for officers. It was in Wehrkreis IX – military district IX. ‘Oflag’ was the German abbreviation of its full title. It was the senior camp or Hauptlager, hence the ‘H’ and Oflag IX A/Z at Rotenburg an der Fulda was its sub camp, or Zweiglager, hence the ‘Z’. Rotenburg was eight miles south of Spangenberg. Somewhat confusingly, Oflag IX A/H was itself divided into Upper Camp, in the Schloß and Lower Camp in the former manor of Elbersdorf, a village on the edge of Spangenberg. Between them the three sites held around 900 British and Empire prisoners. Both camps also held Polish prisoners captured whilst serving alongside the British Army. In the camps the men called themselves ‘Kriegies’ from Kriegsgefangener, the German for prisoner of war. Once liberated their formal title changed to RAMPs.

At both camps the Kriegies included men captured at all stages of the war. The oldest group were men captured in Norway in the spring of 1940. They were about to start a fifth year in captivity. Lieutenant W.K. ‘Butch’ Laing, at Oflag IX A/Z, had been captured in Norway whilst serving in the Sherwood Foresters. In a regimental photograph taken just before the war, Laing appears keen, an enthusiastic teenager. In civilian life he was a teacher at an unnamed public school. He seems to have fitted easily into school and prison camp. Both were disciplined environments with lots of cold water and poor food. Certainly some officers compared their life in prison camp favourably with their time at public school. Laing also appears a little naïve. At one stage in the camp’s evacuation he misidentified Russian POWs being mistreated by their German guards as French Moroccan and Indo-Chinese prisoners under their own French officers.

Oflags IX A/H and IX A/Z in Germany, 1945. (Peter Green)

The Upper Camp exterior of Oflag IX A/H, showing the entrance bridge that crossed the castle’s deep moat. This picture was drawn in 1940 by Captain John Mansel, Queen’s Royal Regiment, before he was transferred from Oflag IX A. Mansel spent time in camps at Thorn and Warburg; by April 1945 he was at Eichstätt in Bavaria. Mansel had trained as an architect at Liverpool University before the war, and his skills were put to use forging travel documents for escapes. (Gillian Barnard Collection)

Laing’s shooting war had lasted less than a month. He joined the Territorial Army in January 1939 and was called up in September 1939. In April 1940 he left Britain for Norway and was captured by the end of the month. On his way to prison camp in Germany, he and others were paraded before Hitler, who told them of his sorrow that Germany and Britain should find themselves at war. Laing might have been forgiven for having similar thoughts, as failure in Norway was followed by defeat in France and it appeared that Laing might not see England again for a very long time. Laing taught basic German at Rotenburg. One of students, Captain Theodore Redway, Durham Light Infantry, recalled that their text books were the children’s stories Hansel and Gretel.

Spangenberg castle is now a hotel. (Ingmar Runge, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence)

Laing’s account of his capture and time in captivity is almost completely devoid of emotion. The occasional exclamation mark and reference to astonishment is the closest he gets to describing his feelings. Most of the men’s accounts are factual and often dry, though emotion does burst through when liberation arrives and many admit to being close to tears or of finding a quiet spot to reflect on their recent past. The men’s military training encouraged brevity. Occasionally they would admit to feeling tired or miserable, but when they do so it was only temporary. Stiff upper lips rapidly reasserted themselves. For example, Captain Ernest Lorne Campbell Edlmann, Royal East Kent Regiment (The Buffs), wrote on Easter Sunday 1945, ‘Woke up filthy and miserable. No Easter feeling at all. But wash and some porridge sends up morale.’ Edlmann was a career soldier. He had been captured in France in May 1940. After the war he returned to his regiment, eventually commanding the 1st Battalion in Aden in the late 1950s. Ernest had made several attempts to escape whilst a prisoner of war. His final and successful one would come in April 1945. When interviewed in 2009 aged 95 he still retained his military directness and confidence. Aged 31 in 1945, he was one of the younger men captured in 1940.

The Upper Camp interior of Oflag IX A/H, inside the Schloß looking back towards the gateway and bridge over the moat, also drawn by John Mansel. The room where Robert Montgomery and the rest of the Wash Kitchen team boiled water for washing and hot drinks, and watched over the camp comings and goings looked down in this yard. (Gillian Barnard Collection)

The Lower Camp of Oflag IX A/H, Elbersdorf. (Imperial War Museum)

A watercolour of the Lower Camp of Oflag IX A/H, painted by Major Borrett, Royal Engineers. Lower Camp was a former farm in the village of Elbersdorf, which then become a hostel. Elbersdorf lay in the shadow of the castle and its hill, northwest of Spangenberg. Inmates of Lower Camp were imprisoned in close proximity with German civilians. In civilian life Borrett was an architect; he was captured when on leave in the Caribbean. His ship was torpedoed and he was rescued and captured by the U-boat crew and returned to Europe. (Green Collection)

Oflag IX A/Z from the east bank of the Fulda. It was originally a teacher training school, becoming a prisoner of war camp in the autumn of 1939. John McIndoe’s watercolour was painted just above the main road running from Rotenburg towards Kassel. In front of the school building it is just possible to make out the wooden hut built to hold Red Cross parcels. (Otago Settlers’ Museum, New Zealand)

The view from Oflag IX A/Z, painted in May 1943. In the foreground the Red Cross parcel hut is beginning to take shape, whilst in the distance above the trees is the spire of Rotenburg’s Lutheran parish church, dedicated to St James. (New Zealand War Art Collection)

The building remains the home to Jakob Grimm Schule, a secondary school, on the outskirts of Rotenburg. (Peter Green)

Ted Beckwith produced a magazine, The Quill, at most of the camps he was held in. The magazine was original text and images bound between wooden boards and passed around its readers. Finding a reliable source of paper was a constant problem. (Green Collection)

One corner of Rotenburg’s small parade ground in the autumn of 1943. Although by this time Rotenburg camp had only held British and Commonwealth POWs for a year, most of its inmates had been imprisoned for three years. (Otago Settlers’ Museum, New Zealand)

Captain E.G.C. ‘Ted’ Beckwith, also captured in Norway whilst serving with the Sherwood Foresters and held in Oflag IX A/H at Spangenberg, was older than Edlmann. He was 40 years old in 1945 and had 18 years service in the Territorial Army before being captured in Norway. He was an employee of Imperial Tobacco in Nottingham and after the war he went on to become a director of the company, before retiring to Oxfordshire. Beckwith had a life-long interest in literature and prison life allowed him to pursue it more fully. He created and edited the Quill, a literary magazine. It was entirely hand produced, each edition a single copy that was passed from ‘subscriber’ to ‘subscriber’. Thirty-one editions were produced in the various camps that Beckwith passed through. The 31st Quill was ‘published’ three weeks before he was liberated. Beckwith compiled an omnibus edition that was published by Country Life in 1947.

One of his poems, written on 4 September 1942 whilst he was briefly held at Rotenburg, discusses the contradiction between the prisoner’s experience and that of the previous inhabitants of the camp buildings. The sorrow it expresses is melancholic, rather than desperate. Melancholia better matched the stoicism, the calmness under pressure, that were expected of an officer.

AUSGANG ZUM GARTEN

[Inscription over a door in the hall at Oflag IX A/Z,

which was formerly a girls’ school.]

What high ideals inspired its builder’s minds

This nursery for Teutonic womankind

On Fulda’s bank, hard by the little town

On which the sheltering tree-clad hills look down

We cannot know. Imagination plays

With scenes and sounds of bygone, happier days

When Mädchen laughter echoed through its floors

From roof to hall, and carried out-of-doors

Into the garden, green then, where the breeze

Stirred, as it does today, the chestnut trees.

Today! The smiling valley lies as green

Among its hills, and Fulda flows between

Its banks, as ageless as the summer skies

Which form their canopy.

But other eyes

Look on the new-reaped fields beyond the wire

(High, tangled barbs) – and in those eyes desire,

And wistfulness, shadows of private troubles,

Longing for other hills and farms and stubbles…

And other feet now tread the gravelled ground,

That once was garden, tramping round and round.

Beckwith combined his writing with breeding canaries. In a world where there was no privacy, there was also none of the intimacy that comes from family or pets, so Beckwith found some of that emotional satisfaction from his canaries. ‘Canary’ was also the nickname the prisoners gave to their secret radios. Rotenburg held a man whose interest in bird life was more academic. It led to him publishing a monograph on the goldfinch after the war. Lieutenant Peter Conder, Royal Signals, had been captured with 51st Highland Division. After the war he he became Warden at Skomer Island field study centre, before becoming the Director of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Whilst at Rotenburg he recorded seeing an albino buzzard for a couple of years, as well as irregular sightings of sea ducks and sandpipers on the Fulda. Conder was not the only prisoner with an interest in wildlife. His notebooks include a record contributed by Ernest Edlmann of a hare that, after being disturbed by a party of walkers on parole, had ‘jumped into the river that was quite full and flowing, swam to the other side splashing a bit, on reaching the far bank resting for some time’.

The fall of France led to the capture of more senior staff than at any other time in Europe. In 1945 Spangenberg held 46 colonels, including Lieutenant-Colonel E.H. Whitfield of the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, whose German POW number was 1. He had been captured in France after the prisoners from Norway so the German prisoner administration was less logically organised than one might imagine. Rotenburg held more young men and by 1945 it had only seven colonels amongst its inmates.

The Senior British Officer (SBO) at Spangenberg was Colonel Rupert Holland, Royal Artillery. Holland had been the town commander at Calais in May 1940. He was captured with the rest of the Calais garrison on 26 May 1940. More fortunate than some of the others captured at Calais, he was moved by car, lorry and train to his first camp, Oflag VII C, in a castle at Laufen in Bavaria. Most walked to the Rhine.

As the SBO of both Upper and Lower Camps at Spangenberg, Holland was involved in negotiations with the Germans and in the absence of German camp records his diary provides the little that is known of German planning for the time when Allied troops might arrive. Holland’s diary was written after the war. It is clear, concise, almost a civil service note of his time in camp. Perhaps he was not such a stuffed shirt; Holland’s nickname was ‘Pixie’, given to him whilst in his first camp at Laufen, where he made a hat from a greatcoat pocket that stuck up like a pixie hat. Although the men’s accounts often lack emotional content, they certainly did have worries. The major one was how would the war end for them? Massacres or hostage taking had long been topics of conversation in the camps. In 1944 the Senior British Officer at Rotenburg had warned the War Office that there was concern in the camp that the Germans might massacre them at the end of the war. This might not have been done by their own guards, but more likely by retreating troops taking revenge for Allied successes or by diktat from Berlin. Following the bombing of Dresden, Goebbels suggested that Allied POWs should be shot as a reprisal, but with the Allies holding large numbers of German POWs and the risk that it might provoke the use of gas or biological weapons, the idea was dropped. At Rotenburg, after more senior officers refused to produce a plan to avert a massacre, Captain Richard Page, Royal Artillery, created a scheme for the prisoners to take over the camp, imprison the guards and move into the nearby woods to wait for liberation. His plan required prisoners armed with chair legs to overcome the guards with their rifles, so perhaps the more senior men showed more wisdom. Lieutenant-Colonel Frost, 2 Para, had urged a similar plan on senior officers at Spangenberg. To his disgust, his plan, which included doping the guards before an assault on the guard house under the cover of smoke bombs by prisoners armed with hockey sticks, was rejected.

The most immediate concern, however, especially in early 1945, was the lack of food. Article 11 of the Geneva Convention required that the ‘food ration of prisoners of war shall be equivalent in quantity and quality to that of the depot troops’. By 1945 the Germans were finding it hard to feed their own troops and the destruction of the German railways by Allied bombing meant that Red Cross parcels were becoming rarer. During the war the Red Cross tried to provide each prisoner with the equivalent of one parcel a week and at Rotenburg the supply was at around this until the winter of 1944. It then dropped to half a parcel a week in 1945 and the supply had all but dried up by March 1945. The last batch of parcels for the two camps was sent in mid-March. It did not arrive. Instead it was diverted to the main prisoner of war hospital in the Wehrkreis, Reserve-Lazarett Obermaßfeld, 30 miles away, which was in greater need.

The daily food ration, drawn by John McIndoe in August 1944, before it was further reduced. It demonstrates the essential role of Red Cross parcels in supplementing the prisoners’ diets. (New Zealand War Art Collection)

Red Cross parcels supplemented and at times replaced absent German rations. A wooden hut had been built at the front of the Jakob-Grimm-Schule to hold the parcels and allow them to be searched for contraband – including escape equipment – before being released to the men. (Otago Settlers’ Museum, New Zealand)

Harry Roberts, 24 in 1945, was one of the youngest men whose diary has survived. His account was published as ‘Capture at Arnhem’ in 1999. Like Ernest Edlmann, Lieutenant Harry Roberts, REME, wrote his account of capture at Arnhem and life as a prisoner. Unlike Edlmann, who wrote up his notes in 1945, Harry Roberts waited until 1990. The combination of the immediate and raw response of the diary with a later response that drew on his wider memories makes his record extremely valuable.

Harry Roberts recorded the amount of food provided by the Germans, or more likely that which was expected to be provided, from 5 March to 8 April. He estimated the average intake per day from German supplies was 1497 calories. The current level recommended by British nutritionists is 2550. Ominously his records are preceded by a table describing the effect of starvation on a cat, with percentages of tissue loss. The entry concludes with the comment that animals typically die when their body weight has been reduced by 60 per cent. During March 1945 Roberts recorded the expected German rations for the month:

Margarine

170g (6oz)

Sugar

140g (5oz)

Meat and wurst

200g (7oz)

Potatoes

2400g (5lbs)

Coffee

14g (1/2oz)

Bread

1780g (4lbs)

The bread was made from dark rye flour and had such an effect on the men that many former prisoners refused to eat any kind of brown bread after the war. A modern British sliced loaf weighs 800g. So the men were expecting the equivalent of two loaves of bread during the month.

Special meals described as ‘bashes’ are a regular feature of prisoners’ diaries. ‘Bashes’ were often prepared by the men themselves from food they had managed to squirrel away. Captain E.H. Lynn-Allen, Gloucestershire Regiment, defined ‘Bash’ in a ‘Glossary of Words and Phrases’ for the Quill:

Bash (To). 1.

Indulge in gastronomic excess (if possible, at someone else’s expense).

2.

To consume at a sitting

Gastronomic excess would not have matched modern definitions of either gastronomic or excess and, with the exception of meals to celebrate the Rhine crossings in March, were few and far between after Christmas 1944.

The former Manager of the Droitwich Spa Hotel, Lieutenant Robert Lush RASC had been captured whilst serving with the Expeditionary Institute in France in 1940. According to John Logan in Inside the Wire, Lush was appointed catering manager at Rotenburg after a scandal with the existing catering. His portrait was painted by David Feilding. (Imperial War Museum)

Some meals were provided by a central kitchen and others by the men themselves in their dormitory messes. Both relied heavily on Red Cross food parcels. From the summer of 1943 Rotenburg’s kitchen was run by Lieutenant Robert Lush, Royal Army Service Corps, who, pre-War, had managed the Droitwich Spa Hotel. It is not clear who provided a central food service at Spangenberg. However Captain Robert Montgomery MC, Royal Engineers and Commandos, was part of a team heating water for washing and afternoon drinks at Upper Camp. The team used camp rubbish as fuel for the boiler. The Wash Kitchen was close to the main gate and was a useful vantage point to observe the guards. Also near the main gate was a group of small rooms that housed colonels and senior majors in groups of around four to a room. The other men were housed in communal rooms. Montgomery remembered that Room 19, which predominately housed young subalterns, was the source of most of the jokes and stupidity in the camp. William Watson, Black Watch and Commando, recalled that this room was also known as the ‘Arab Quarter’. Montgomery and Watson were survivors of Operation Chariot, the raid on the dry dock capable of holding the Tirpitz at St Nazaire. The leader of the raid, Lieutenant-Colonel Augustus Newman VC, was also held in Spangenberg. Their presence is a reminder that although many in the camps came from France in 1940 or Greece and North Africa in 1941, there were men captured throughout the war, including some taken when the Allies were in the ascendant in North Africa and Italy – and of course during the disaster at Arnhem.

Lieutenant-Colonel John Frost was one of the men captured at Arnhem who were sent to one of the two camps: 55 to Spangenberg and 36 to Rotenburg. These last additions were younger and fitter, even if many were wounded. Lieutenant-Colonel Frost was the most senior, but unlike the older Colonels captured in Norway or France, he was only 33. His wartime biography has little to say on his time at Spangenberg or at Obermaßfeld hospital where he was transferred when his wounds proved reluctant to heal. He was certainly disappointed by the lethargy of many of the men he met at Spangenberg. In March 1945 his suggestion that the prisoners seize control of the prison hospital as the Americans approached was overruled.

Lieutenant Hugh Harry Langan Cartwright, 2 South Staffs from 1st Airborne Division, published his experiences of Arnhem and in prison camp afterwards in a piece for the Airborne Museum at Oosterbeek. It has only a few paragraphs on prison life.

Lieutenant Alan Thomas Green, 1 Border, kept a prison diary in great detail until January 1945, when it stops with no explanation. He later compiled notes on his experiences after this date. Of all the Arnhem captives Harry Roberts’ account is the most detailed.

The Swiss Government made what was to be the last inspection of the camps in early March 1945. They found the prisoners in good spirits. The prisoners’ concerns over their use as hostages or of a possible massacre were perhaps not best raised with the Swiss in the presence of the Germans, who included officers from Berlin. Several prisoners comment on the reassurance they got from being marched out of the camp with their usual guards. Had they been replaced by SS troops the prisoners’ mood would have changed. The splendidly named Lieutenant Terence Cornelius Farmer Prittie, Rifle Brigade, remembered at Oflag IX A/H that one of the few things they were told in advance of the evacuation was that they would be under the escort of their own camp guards.

Only slightly less alarming was the idea that they might be held hostage, perhaps in a redoubt in the mountains of Bavaria. The idea of a Nazi last stand based on underground factories, stockpiled supplies and SS divisions became prevalent amongst the Allies in 1945. An intelligence briefing for the British 21st Army Group, prepared in March 1945, suggested that the Redoubt was centred on Salzburg and Berchtesgaden, ‘a region from which the most persistent reports emanate concerning the arrival of ammunition, food and other supplies’.

Nazi redoubts were illusory; but they had a strong hold on the minds of Germans and Allies alike. It was therefore only natural that this would be a concern to all POWs. John Logan, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, published his wartime experiences as ‘Inside the Wire’ in 1948. ‘We often try to visualise the end as it concerns us … Some visualise the Germans carrying on a guerrilla war in Bavaria and the Tyrol and our being moved down there.’ Logan’s diary covers almost the whole period of his imprisonment from 1940 until the day before the camps were moved. On his arrival at Rotenburg, in July 1943, he thought it a ‘pretty dull spot’ with low morale caused by too many of the men being older prisoners. By November he describes it as a ‘most comfortable building’. Logan was 38 in 1945, so he was not one of the youngest prisoners himself.

Optimists in both camps believed that they would be abandoned by their guards and peacefully liberated by Allied troops as the front line rolled over them. The belief was based on the argument that the Germans would not want to burden themselves with moving prisoners when they had more than enough problems in moving their own troops. Though logical, this overlooked the high value that the Germans attached to their prisoners. During one of Hitler’s military conferences in January 1945, the fate of Allied airmen, prisoners at Stalag-Luft III, who were now close to the Eastern front, had been discussed. Göring suggested that they should be left for the Russians. Hitler’s response was, ‘They must leave, even if they march on foot. The Volkssturm will be mobilised for that. Anyone who runs away will be shot.’

Stalag IX A at Ziegenhain, a grossly overcrowded camp for NCOs and other ranks, was liberated by American troops with its inmates in situ. Stalags were intended to be administrative centres for the working parties – Arbeitskommando – in German agriculture or industry. In the confused conditions of spring 1945 Ziegenhain simply filled up with men as the Germans were unable to allocate enough of the incomers, many Americans from the Ardennes, to external kommandos. In the end the German attitude to their prisoners at the two Oflags was simple. The men as officers were a valuable resource, even if many were old and out of touch with modern warfare.

Like Harry Roberts, Captain John Humphrey Sewell, Royal Engineers in Oflag IX A/H, had been employed by the London and North Eastern Railway, also in York, before he was called up and then captured in Greece in 1941. John Sewell’s diary is perhaps most interesting for its almost obsessive attention to meals and food. This entry is typical:

Wednesday 14th March

Breakfast 8.45: 2 slices bread (incl. 1 crust) with Ger. marg and Ger. jam

cup of tea with RX dried milk.

Lunch 12.30: the usual – 1 plate vegetable soup, ½ slice bread with Ger. marg cup RX cocoa with cond milk RX and 2 sacherins.

Supper biscuits and 2 ovaltine tablets.

Sewell retained his railway associations as a prisoner of war. Included in his papers is a photograph of fellow prisoners that has, along with their signatures, the names of their peacetime railway employers.

Sewell shared a room at Spangenberg with Captain Ralph Venables Wilbraham MC, Pioneer Corps. Ralph Wilbraham was born in 1893, making him at 52 one of the oldest men in either camp. He had won the Military Cross whilst serving as Brigade Signals Officer with the Cheshire Yeomanry in Palestine in the First World War. Called up in 1939, he went to France as a Captain in the Auxiliary Military Pioneers and was captured near Rouen in June 1940. After time in various camps he eventually arrived at Oflag IX A/H. After the war he became the Director of the Cheshire Red Cross.

Another older officer, who had also seen service in the First War, was Lieutenant Edward Baxter, Royal Army Ordnance Corps. He was 48 in 1945 and in Oflag IX A/Z. Baxter was captured in Greece in 1941. In his liberation questionnaire he gave his pre-war occupation as ‘writer’. Baxter’s account of his life as a prisoner, which he wrote later, provides more background than others but is still light on emotional content. Baxter was one of the prisoners who did not believe that the Germans would move them but did record rumours that they would be marched away. He attended a lecture given by one of the survivors of the appalling winter marches through the snow from the East, ‘It had been a terrible thing, and several men had died. We did not relish the prospect at all.’

Two men from Spangenberg captured in France in 1940 wrote an account of their time in captivity and their attempts to escape that became a best seller in the early 1950s. South to Freedom was written by Terence Prittie and Captain William Earle ‘Bill’ Edwards, Royal West Kent Regiment. Lieutenant Prittie went on to be a more well-known writer than Edward Baxter. He had been captured at Calais along with Colonel Holland in 1940. He made the first of his six escape attempts whilst still in France being marched eastwards. In January 1943, as a repeat escapee, he was to have been transferred to Oflag V C at Colditz, but at the last moment it was found that Colditz had no space and he was sent to Spangenberg instead. Terence Prittie believed strongly that the Germans would not simply abandon their prisoners, ‘That many officers still resolutely believed that the Germans would leave us to take our chances in Spangenberg was an amazing tribute to the myopic futility of war-weary minds.’ Prittie wrote a series of articles for the Cricketer magazine whilst at Spangenberg that were posted back to London. Each article was written, as Prittie remarks, without access to Wisden and yet they are packed with statistics and team details.

It was possible to let off steam playing sport. Spangenberg had a sports field that men from Upper and Lower Camp were allowed to use under parole but not at the same time. Contact between the two sites were very limited. It was therefore very unusual in December 1944 when the pantomimes from Lower and Upper Camp were performed at both sites. Ted Beckwith was allowed to visit Upper Camp to collect contributions for the Quill.

Cricket was possible within Lower Camp, but sport within the Schloß was limited to using the moat for cricket, football and hockey, on a very small pitch. Flooded and frozen, it was used for curling in the winter. Rotenburg had to make do with its small parade ground for most sporting activity, but the men were allowed access to what John Logan called a ‘rough mossy piece of course pasture’, where occasional team games could be played. It had been an athletics track. More regular sport was to be had on the camp’s skating rink each winter. Half of the parade ground was flooded within snow banks. Once the water froze there was space for skating and ice hockey. In January 1945 a Canadian hockey team drew with England 4-4.

The parade ground at Rotenburg was not large, but during the winter months it became traditional to surround part of it with low snow banks and then flood the interior to create a rink for skating and ice hockey. International matches were held, usually featuring a Canadian team. (Otago Settlers’ Museum, New Zealand)

Gambling was a major activity in the camps. ‘Race meetings’ were popular: model horses were moved by a throw of the dice around a course. The meeting drawn by McIndoe on 29 May was threatened with cancellation when Oberstleutnant Brix learnt that one of the horses had been christened ‘New Commandant – By Little Adolf out of What’s Left’. John Logan’s diary for 22–28 May 1944 records that two prisoners had been marched before the Commandant as a result. (Otago Settlers’ Museum, New Zealand)

Most of the Canadians had arrived in the camps after Dieppe, but the Arnhem operation brought ‘CANLOAN’ officers; subalterns, of whom the Canadian Army had a surplus, who served with British regiments. The unusual regimental affiliation made many existing prisoners suspicious of the newcomers until news of the scheme spread through the camps.

There was of course no opportunity to play polo, nor the other favourite activity of former cavalry regiments, hunting. Major Bruce Middleton Hope Shand, 12th Lancers, the father of the Duchess of Cornwall, felt the loss. Shand had been captured in the confusion of the Eighth Army’s pursuit of the Afrika Korps after El Alamein. Shand was able to get into the surrounding country on parole walks and in parties to cut wood for the castle’s central heating boiler. It is unlikely that ‘Gone away or the Harkaway Hunt’, a board game for two players devised by Ted Beckwith, fulfilled Shand’s fox hunting desires. Ted Beckwith also did some yacht racing at Spangenberg, but again sadly it was one of his board games.

Captain Ian Reid, Black Watch, was another horse-lover and like Shand was unfortunate to have been captured as the Allies were in the ascendancy in North Africa. His account of time in and out of Italian camps and his final escape was published in 1947 by Gollanz as Prisoners at Large; the Story of Five Escapes. Reid was an inveterate escapee and was one of the first to part company with Oflag IX A/Z, on 29 March 1945. In 1970 he achieved a life-long ambition by becoming the Point-to-Point correspondent on The Times.

The Canadians introduced baseball and softball to Rotenburg. One game is described in a poem written in the camp, a match between the ‘Mandarines’ and the ‘Tomcats’, on which men had ‘pledged their pants and their back pay’. A chaplain describes there being three ‘firms’ of bookmakers at Rotenburg. Bets were made on almost anything, including the next day’s weather. Favourite bets were on the date of their liberation or the end of the war.

Escape attempts occurred at both camps. The only successful one from Rotenburg was in early 1943 by two Indian Army officers who reached Switzerland. Unfortunately, the British official histories of the camps do not explain how they got out of the camp. Spangenberg Upper Camp in the Schloß and sitting on its rocky promontory was not an easy place to escape from. For almost a year from July 1942 there was work on a tunnel, before the Germans discovered it. The other route out of Upper Camp was by variations on booms and aerial runways to cross the moat. Two men did get across the moat in October 1943 and reached Darmstadt before being recaptured. A tunnel at Lower Camp that was planned to go 40 yards collapsed after 19 yards.

Bill Edwards, who collaborated with Terence Prittie on an account of his time in camps and their escape attempts, was also a pretty regular escapee. He had been captured whilst serving with 7th Battalion Royal West Kent Regiment. His penultimate escape attempt was from Obermaßfeld prison hospital in 1943, where he had been temporarily transferred from Spangenberg. He was within 15 miles of the Swiss border when he was recaptured.

The War Office history of Rotenburg rather oddly omits the last escape from the camp, made in September 1944. Seven men, disguised as orderlies under the supervision of two other prisoners disguised as German guards, walked out of the main gate having made a copy of the key to the gate. Lieutenant Hamish Forbes, Welsh Guards, describes the key being dropped accidentally by a guard, found, copied and returned to the Germans, in the hope that its loss would not be reported and new locks fitted. The ‘guards’ had wooden rifles and uniforms made by the prisoners. The men were all back in the camp in October. Whilst in police hands, they were threatened with being handed over to the Gestapo, as a result of the hardening of German attitudes to escape following the breakout from Stalag Luft III. Forbes had been captured in France near Dunkirk in 1940 and in all made an impressive 10 escape attempts.

One of the oddest escape attempts was a tunnel at Rotenburg that started above ground, on the first floor. The tunnel went into an outside wall in an upstairs toilet and then down inside the rubble-filled core of the wall. It was to have then gone under the surrounding concrete and asphalt, and out beyond the perimeter wire. The Germans discovered the spoil from the tunnel dumped in the roof space in June 1944, but it took them a month to find the tunnel. When the Jakob-Grimm-Schule was renovated in the 1980s there was still rubble from the tunnel lying on the rafters in the roof.

The most senior officer at Rotenburg to record his experiences was a member of the escape committee. Major Edward James Augustus Howard ‘Peter’ Brush, Rifle Brigade. Peter Brush was Security Officer at Rotenburg. He had been captured like Rupert Holland and Terence Prittie at Calais in 1940. He was 44 in 1945. His diary shows him as a blunt, no-nonsense man. An Ulsterman, in the 1970s he confided to friends that he could sort out the IRA very quickly if he and his old regiment were given a free hand. Brush’s account includes this exchange concerning the end: