The Rage to Live - The International D.P. Children's Center Kloster Indersdorf 1945-1948 E-Book

Anna Andlauer

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: epubli

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book documents two historical humanitarian efforts to help the youngest victims of National Socialism in postwar Germany: After the liberation of the concentration and labor camps, from July 1945 to July 1946, a team of UNRRA pioneers provided 613 Jewish and gentile child survivors in Kloster Indersdorf (near Dachau) with the initial help they needed to pick up the pieces of their shattered existence and go on with their lives - either in their home country or in a completely different environment. Taking care of hundreds of young Holocaust survivors and other displaced children posed a challenge hitherto unknown. The humanitarian workers focused on the children's individual needs and psychological responses to persecution and displacement. They listened attentively when the child survivors talked about their suffering and loss; they had to understand that these traumatized young people urgently needed to gain control over their haunting experiences. From August 1946 - September 1948 in the Jewish Children's Center Kloster Indersdorf, the Zionist kibbutz movement Dror, along with the UNRRA, also had to meet the basic needs of hundreds of young Holocaust survivors from Poland, Hungary and Romania. The youth leaders offered schooling, games, sports, concerts and cultural activities. But as their primary aim was to prepare these child survivors for their future life on a kibbutz in Erez Israel, they also engaged them in helping with farm and household tasks, they practiced roll-calls and self-defense, and they taught them Zionist and socialist principles. Sixty to seventy years later, the author interviewed more than a hundred survivors who were either in the International Children's Center or in the Jewish Children's Center Kloster Indersdorf. She paints a vivid picture of everyday life in both children's centers and creates portraits of many of these child survivors "then and now".

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of Greta Fischer

1910-1988

About the Author

Anna Andlauer majored in English, sociology and art history. During her years as a high school teacher, she began guiding tour groups at the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial, and this focus on contemporary history eventually found expression in exhibitions and newspaper articles on the history of the Dachau Camp. She is the author of Du, ich bin der Häftling mit der Nr. 1 about Claus Bastian, the first registered prisoner at the camp. While teaching in German schools and participating in teaching exchanges in the UK and the USA, she always invited Holocaust survivors to address her classes. Since 2008 she has researched the International D.P. Children’s Center Kloster Indersdorf, tracing survivors now spread all over the world, who had been cared for at the center in the immediate postwar era. She has interviewed them and invited them back to visit “their cloister” to meet each other and local people, and to talk about their experiences.

Anna Andlauer

The Rage to Live

The International D.P. Children’s Centers Kloster Indersdorf 1945 - 1948

This book was first published in German in 2011: Zurück ins Leben. Das internationale Kinderzentrum Kloster Indersdorf 1945-46.

In 2017 the book was updated and expanded to include the Jewish Children’s Center at Kloster Indersdorf, from August 1946 – September 1948.

This book is the English version, published in 2018. Translation and editing was supported by Diana Morris-Bauer.

Copyright© 2018

Anna Andlauer

Hauswiesen 1

D-85757 Karlsfeld

All rights reserved

Distributed by: epubli – a Service of neopubli GmbH, Berlin

Contact according to EU Product Safety Regulations:

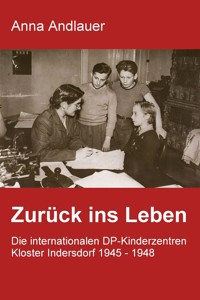

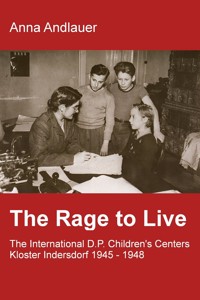

Cover photo: Helen Steiger interviewing Russian orphan Lene Walekirow while Walter Hahn (left) and Pjotre Fabiszewski listen in.

Title photo: Greta Fischer playing with young survivors

at Kloster Indersdorf

Contents

Preface

Foreword

Help for Survivors

The “International D.P. Children’s Center Kloster Indersdorf” Opens Its Doors

Helpers in the pioneer project

Displaced children arrive

Jewish child survivors

Gentile displaced children

Displaced babies

Creating a Therapeutic Environment

Satisfying the need for food

Struggling to restore health

Individual clothing styles and self-esteem

Survivors cling to each other

Babies need individual care

Easing the young people’s hearts

Identifying the children

Searching for relatives who might have survived

Conflicts

How much emotional guidance is needed?

Suddenly discovering sexuality

Clashes with the German locals

Should survivors help with housework?

Should Jews and Gentiles be separated?

Education and Leisure

General education

Vocational training

Leisure activities

The Children’s Center Changes

Dealing with unanticipated problems

Significant fluctuations

The first kibbutz arrives

Attempting to plan for the future

Repatriating Gentile children and teenagers

The move to Prien am Chiemsee

Beit Jeladim Ivrit, the Jewish Children’s Home at

Kloster Indersdorf (1946-1948)

Learning to Live with the Aftermath

And How Life Went On

Greta Fischer – Portrait of a Remarkable Life

Resources and Works Cited

Archives, Journals, and Periodicals

Films

Books

Photos

Internet Sites

Notes

Preface

Every year in July, dozens of senior men and women from around the world return to Germany. They have accepted an invitation from the concentration camp memorial at Flossenbürg, and their motives to come vary. They set out on the arduous journey to mourn their murdered family members, friends and comrades. They travel for the sake of finding traces of their own suffering, looking for graves and for those still missing. They come out of a sense of personal or family responsibility, from political conviction or psychological necessity.

Participants are getting on in years, the youngest among them are today in their mid eighties. As children or teenagers they managed to escape the clutches of the National Socialist concentration camp system. Driven along on one of the most notorious death marches, they were liberated literally in the very last minutes before it was too late for them. They had survived systematic murder by the National Socialist regime, most often the only members of their families to have done so.

Martin Hecht was only fourteen when he survived Flossenbürg concentration camp. Here he is next to his October 1945 picture from Kloster Indersdorf on permanent display at the Flossenbürg memorial site.

In May 1945, these twelve- to fifteen-year-old children found themselves in a dramatic situation. The end of their imprisonment in camps meant far more than a mere liberation; it propelled them into a full realization of their loss. They had been robbed of all their family and social relationships. Their parents and relatives had been murdered; their childhood homes had ceased to exist. The experience of absolute vulnerability had had such a profound and shocking influence on them that normal social roles were turned upside down. As a result of living in permanent fear of death – a terror from which their parents had been unable to protect them – they had lost every shred of trust in the world of adults. In the camps, these youngsters had been painfully forced to fend for themselves if they were to survive. Survival had consumed all their energy. In terms of their psychological development, they stood on the threshold of puberty while disoriented and in extreme need of care. Given their experiences, however, they were no longer really children or youths.

For the Allied troops, the military government, and international charities, taking care of these young concentration camp survivors posed a challenge hitherto unknown. First, adequate housing and sufficient food had to be provided. The United Nations refugee organization UNRRA established children’s centers and tried to meet the humanitarian and pedagogical challenge. Now that they were sheltered and cared for, the young people were encouraged to leave the camps behind them and to regain a life appropriate to their age. They were compelled to literally rediscover their real names, relearn basic social roles and gradually place an increasing trust in adults.

In this book, Anna Andlauer describes the history of the UNRRA Children’s Centers at Indersdorf. The story, however, encompasses far more than local historiography. From the start, the author was interested in the lives of the young camp survivors and their thorny paths back to “normal” living. She began a systematic search for the “Boys” of Indersdorf and discovered along the way far more than she had at first expected. Her meeting with them confronted her with history and narrative, trauma, hope, and survival. Research for this book made Anna Andlauer not merely an explorer, but a social worker, counselor and friend of the “Boys,” now quite advanced in years.

These roles have been decisive for both the structure and style of the book. The author is an empathetic listener and an equally empathetic writer. In dense descriptions Anna Andlauer repeatedly allows her emotions to emerge; she approaches the feelings and sensations of these youths, and this permits her to convincingly portray their former survivors’ worlds.

She reconstructs the individuality of these former teenagers, today’s eighty-year-olds. This constitutes the book’s humanizing achievement.

The study also honors the undeservedly obscure social worker Greta Fischer who, with others, cared for the young survivors and after whom in 2011 a school in Dachau was named – this dedication, too, to the author’s credit. The story of the “Boys” has now been told by Anna Andlauer. And we can’t thank her enough.

Flossenbürg, summer 2018

Jörg Skriebeleit

(Director, Flossenbürg Concentration Camp Memorial Site)

Foreword

“It was astonishing to see what a miracle could be worked for children orphaned by the Holocaust when the right thing was done,”1 Greta Fischer discovered. She was one of the social workers on a UN team that set to work in Bavaria’s Kloster Indersdorf to receive and help displaced children and youths. Here in an old monastery not far from Dachau in July 1945, the first international children’s center in the American Zone in Germany was set up, an orphanage where Jewish and Gentile children and teenagers of various nationalities were cared for together, including those liberated from concentration camps, former forced laborers, and children of forced laborers — young people who had survived the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust and who had to be helped back on the road to life.

These young people had endured so much in the previous months and years, their suffering having been not only physical, but also, and even more important, psychological. They were devastated and highly disturbed. They had lost their next of kin, been removed from environments they could trust, and been forced to witness incomprehensible horror. All this left indelible marks on their souls.

In what state were these young, neglected, traumatized youths after liberation? What needed to be done to help them in the short and long term?

It was, of course, impossible to effect a real rehabilitation of young victims of National Socialism within six months or a year. Nonetheless, in the first months after liberation, significant strides were made.

Hans Keilson, who researched long-term effects of persecution, recognized that what occurred immediately following the war would have a decisive influence on survivors’ later lives: “Above all, I realized the meaning of the period immediately following the war as the children became aware of their fate and the help they were able to receive or miss out on during this important period.”2

The United Nations pioneers from UNRRA Team 182 faced a challenge like no other. There was no one to advise them on how these Holocaust victims would be able to overcome the emotional ramifications of their own survival. And yet they were endowed with the mission of not only satisfying the basic physical needs of hundreds of young people at a critical maturational phase, but also paving the way for them to form new lives. The UNRRA team wanted to help relocate these young survivors to where they could find solid prospects for a new life outside of Germany.

Indersdorf Survivors’ Reunion participants in front of a picture of Greta Fischer in July 2008. (from left) Hans Neumann, Erwin Farkas, Martin Hecht, Avram Leder, Eva Hahn, Walter Hahn, Zoltán Farkas, Michael V. Roth.

For the sake of research as well as human relationships, it is especially remarkable that in recent years more than one hundred former residents of this children’s center could be found: in the USA, Canada, Brazil, England, Belgium, Poland, Hungary, France and Israel. Today – over seventy years later, that is – they are returning to visit “their” Kloster Indersdorf once more. They look back over the many years that have gone by, their childhoods, their youth during the Holocaust and how things went for them afterward. In the meantime, they remain eyewitnesses who have managed to live their daily lives in vastly different environments surprisingly well despite profound trauma.

These observations – even if valid for only a portion of those cared for at the time – lead to the question, what were the qualities and resources necessary to help these children regain their physical and mental health despite conditions immediately after the war?

Greta Fischer, the major chronicler of events, was in the midst of the action as she put her schooled therapist’s eye to work in writing about her experiences. In the beginning of 1946 she penned a 33-page report about her UNRRA team’s work with these “lost children of Europe.”3 The report is written as an international appeal to receive these displaced young people and give them an opportunity. Similarly, when later employed in Canada, Morocco, and Israel, she sought ways to promote her work with these young Holocaust survivors.4 She constantly insisted that “the story of the children from Kloster Indersdorf must be told — their will to survive, their indescribable rage to live.”5

From her experience as a social worker, Greta Fischer saw above all in these traumatized youngsters, “proof of the resilience of people and the indomitable courage of the human spirit.”6 Conducting a type of longitudinal study in the first four decades after the war, she found that many of her former charges became productive and successful members of their respective communities, but “when we talk about their personal happiness, ... they’re not so communicative.”7

In the 1980s, Greta Fischer stood again in front of the door of Kloster Indersdorf to see once more her former workplace. But because the old Bavarian convent now housed a lively school, and since hardly anyone present there knew anything about the place in the immediate postwar years, she was sadly denied entry. In December 1986, fewer than two years before her death, she wrote to her friend Esther Halevi that, since she had seen the film Shoah, she had become even more firmly convinced that the story had to be told. But how, she wondered, admitting that she nearly phoned Elie Wiesel, whom she had met in Toronto, for help.8

Following her aunt’s sudden death in 1988, Lilo Plasches found among Fischer’s papers reports of Indersdorf and many unique historical photos9 — expression of her unfulfilled desire to let the world know about her experiences with the youngest of Nazi victims. This book serves to convey some of the story Greta Fischer wished to tell. The text is based on her writings as well as a video interview from 1985. Documents housed in various archives (above all the United Nations Archives), letters and a report from the nuns employed in the convent and especially the survivors’ memories flesh out the picture. Much of what was found, even items of seeming insignificance, speak for themselves, detailing daily life in postwar Kloster Indersdorf and, hopefully, helping to open the doors to former residents who have made return visits from all corners of the globe.

Only since the mid-eighties has German historiography concerned itself with Jewish DPs; it took even longer before attention was paid to the special situation of the youngest victims in numerous children’s centers,10 despite the fact that the fate of the children is mentioned in nearly all publications on the history of Jewish DPs.11 Here we should mention the seminal studies: Juliane Wetzel’s Jüdisches Leben in München 1945-51. Durchgangsstation oder Wiederaufbau? (1987) and Jaqueline D. Giere’s dissertation, Wir sind unterwegs, aber nicht in der Wüste. Erziehung und Kultur in den jüdischen Displaced Persons Lagern der Amerikanischen Zone im Nachkriegsdeutschland 1945-1949 (1993).

This pioneering research notwithstanding, the many efforts to begin life anew in Germany after the war – and to renew daily life in children’s camps in particular – have not received systematic attention.12 The first comprehensive book to address a broad public on this issue appeared in 1994, Angelika Königseder and Juliane Wetzel’s Lebensmut im Wartesaal: Die jüdischen DPs (Displaced Persons) im Nachkriegsdeutschland. It contains the first mention of Indersdorf as an international children’s center and later a Jewish orphanage.

Then in 2006, Jim G. Tobias and Nicola Schlichting dedicated a chapter in their book Heimat auf Zeit. Jüdische Kinder in Rosenheim 1946-47 to the Indersdorf Children’s Center.

This study continues the research begun by Königseder, Wetzel, Tobias and Schlichting and describes the first year in operation of the “International D.P. Children’s Center Kloster Indersdorf” and the entirely different life in Beit Jeladim Ivrit (August 1946 – September 1948), a subsequent orphanage exclusively for Jewish children, housed in Kloster Indersdorf.

Even though I have lived for more than thirty years near Dachau and have been engaged in historical research, I was largely unaware of the story of postwar Kloster Indersdorf. I have Eleonore Philipp to thank for bringing this topic to my attention. I discovered Greta Fischer’s report in the archive of the Heimatverein — a local historical society — of Indersdorf. As a teacher at Markt Indersdorf high school, I assigned a student to delve further into the report and soon recognized the unique value of this historical document. Since then I have been on an exciting voyage of discovery. In archives all over the world I have found photographs and documents, but above all, I have met these child survivors, who immediately after the war took their first steps toward a new life in Kloster Indersdorf.

My research first appeared in Nach der »Stunde Null«. Stadt und Landkreis Dachau 1945 bis 194913 and in the 2010 yearbook of the Nürnberger Institut für NS-Forschung und jüdische Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts [Nuremberg Institute for Research on National Socialism and Jewish History of the Twentieth Century].14 Further publications appeared in volume thirteen of the Dachauer Symposien zur Zeitgeschichte 15 [Dachau Symposia on Contemporary History] and in volume three of the yearbook of the International Tracing Service (ITS).16 The international traveling exhibition Life After Survival illustrates with historical photos and a short film the therapeutic environment critical to the immediate help extended to these child survivors. In January and February 2016, we installed the exhibition in the United Nations Headquarters during the yearly Holocaust commemoration, its themes adopting a new urgency in light of the current global situation in which millions of people seek refuge. We have been able to trace more than one hundred former child survivors to Israel, Poland and above all to the English-speaking world. Many of them have visited, together with their families, “their” Kloster Indersdorf again, to renew acquaintance with one another after all these years and to give eyewitness testimony.17 In 2011 a school in Dachau was named after Greta Fischer, so inspired were the teachers, therapists and school administration by the spirit of her work with child survivors in the postwar years.

The State of Bavaria and the Concentration Camp Memorial at Flossenbürg have been inviting survivors annually since 1995 to Flossenbürg (in northern Bavaria) – a significant gesture in contemporary memorial efforts that, even 70 years after liberation, is recognized by former prisoners and their relatives all over the world. These annual gatherings have permitted me since 2008 to invite those who had been cared for in Indersdorf to revisit “their” center and participate in discussions with peers, to enjoy celebrations and go on day excursions. A ZDF (TV) film Aus der Hölle ins Leben [From Hell Back to Life] documented these events,18 as well as the BR [Bavarian Broadcast Company] film Die Kinder von Indersdorf [The Children of Indersdorf].19

Indersdorf Survivors’ Reunion participants in 2014 at the Greta-Fischer-Schule in Dachau. (left to right) Henia Marcus, Martin Hecht, Abraham Maisner, Leslie Kleinman, Miriam Stein, Erica Spindler, Aida Bar-Hecht and Erwin Farkas. In background, the Author.

I thank all the survivors for their moving stories, photos and documents that became a part of this book, directly or indirectly, especially Salek Benedikt, Jan Topolewski, Manny Drukier, Henia Marcus, Nahum Bogner, Masha Goren and Ester Katz. I’m grateful for their many expressions of friendship and hope that I’ve done them justice in this work.

For generous financial support, without which this project would not have been possible, my special thanks go to the Stiftung Bayerische Gedenkstätten [Foundation for Bavarian Memorials], the Bayerische Landeszentrale für politische Bildungsarbeit [The Bavarian State Agency for Civic Education], the Foundation “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft,” [Remembrance, Responsibility and Future] the BMW Group, the Sisters of Mercy of Saint Vincent de Paul, to the district of Upper Bavaria, to Dachau county, to the community of Indersdorf and the Heimatverein Indersdorf (historical society). Very special thanks go to the team of the Flossenbürg Memorial, the teaching staff of the school Vinzenz von Paul and the Greta-Fischer-Schule, and last but not least, all the enthusiastic supporters of our Indersdorf project, such as Hadas Littman, Tsvi Yeshurun, Tseela Yoffe, Niva Ashkenazy, Miri Nehari, Irma Wilfurth, Elly Ott, Gottfried Biesemann, Inge Künzner and my husband Jörg.

A hearty thanks goes to the relatives and friends of Greta Fischer, who were so generous with photos, documents and personal memories which enriched this book, for example, Micha Plaschkes, Hanna Corbishley, Edward Merkel and Fraidie Martz. I also owe thanks to Ester Brumberg from the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City, Melissa Yaverbaum from the Council of American Jewish Museums and Jude Richter from the US Holocaust Memorial Museum for their cooperation. In addition, I would like to thank Diana Morris-Bauer, Ilse Greif, Michael Buchmann and Jörg Skriebeleit. They scrupulously read my text and made excellent suggestions to improve its content and style. My special thanks go as well to Nicola Schlichting and Jim G. Tobias of the Nürnberg Institut für NS-Forschung und jüdische Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts [Nuremberg Institute for Research on National Socialism and Jewish History of the Twentieth Century], whose constructive engagement, critical commentary, advice about the structure of the study as well as expertise, accompanied me patiently while I wrote. Naturally, mistakes may have crept in for which I alone am responsible. Errors of course may occur but I have done my very best to come as close to the historical truth as possible.

Weichs, summer 2018

Anna Andlauer

Greta Fischer (right) among the ruins of a south German city after the end of the war.

Help for Survivors

On May 8, 1945, the war ended on the European front. Twelve years of National Socialist rule had left widespread material, human and moral devastation and a Europe on the brink of utter chaos. The Second World War, along with the events which a decade later became known as the “Holocaust,” had driven millions of people from their homelands and had destroyed families all across Europe. Among the millions of refugees were those liberated from concentration and labor camps as well as those who had survived the Nazi dictatorship in hiding or by using a false identity. To answer the immediate needs of these abducted, homeless and uprooted people, called Displaced Persons (DPs), food, clothing and medicine had to be supplied. To manage this task, the Allies in their respective occupation zones constructed so-called DP camps. These sprang up wherever the necessary infrastructure could be found: in former concentration camps, in barracks that had served the army or SS, in hotels, monasteries or private homes.20

In the mid-1940s, the Allies had already anticipated dealing with innumerable prisoners and forced laborers after liberation,21 and in November 1943 the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA)22 was founded. As the first organization to establish refugee assistance on an international level, by the end of World War II, UNRRA became the largest transnational relief organization in operation.23 UNRRA’s mission was to provide basic care for countless uprooted and displaced persons in so-called “assembly centers” and to assist them with reconstructing their lives.24 The UNRRA teams were attached to various military divisions and followed the fighting troops in order to support the military in caring for the millions of victims and – whenever possible – preparing for their expected repatriation. The sheer scale of crimes committed against civilians confronted the UNRRA teams with unprecedented human adversity in need of immediate relief. Their task appeared larger than ever before but demanded immediate action.

Meeting of UNRRA Team 182. (from left) Marion E. Hutton, director Lillian D. Robbins, André Marx, Dr. Gaston Gérard, Harry C. Parker, Greta Fischer, Helen Steiger, unidentified.

With only a vague idea of what awaited her, thirty-five-year-old social worker Greta Fischer25 arrived in Germany in June 1945 with UNRRA Team 182. In London, just days before the end of the war, she had signed up as a volunteer to aid a devastated Europe. At an orientation course in Granville, France, she was assigned to Team 182, which was ordered to report to Section G-5 of the Third US Army in Munich for further instructions. “There was no order of the day. Everything was kind of spontaneous. And there was [great] confusion in Germany also. Soldiers coming back from the war, other soldiers coming to help in the liberation … .”26

Fischer was especially worried about the “unaccompanied children,” the young, including teenagers, who were left to wander without their parents or other adult companions.27 “Homeless, emaciated, covered with scars, fearful, bitter victims of robbery, witnesses of horrors – those were the children of liberated Europe.”28 “Lost children” Greta Fischer called these young foreigners who, alone or together in groups with adult displaced persons, lived in provisional camps or ceaselessly searched for relatives and food, asking how and if they would be able to move on with their lives.29 In order to funnel aid directly to these uprooted children and teenagers, UNRRA Team 182 and Greta Fischer were charged with determining the magnitude of these “unaccompanied” young survivors and creating a refugee center for them. The center had to be close to the Munich headquarters of the Third US Army in order to better ensure essential support.30 “[N]obody knew what to expect, the extent of the need, nor the nationality or age grouping of the children.”31 Section G-5 of the Third US Army, responsible for DPs, estimated that in its area alone, there would be 7,000 children.32

So that they could quickly and efficiently fulfill their mission, members of UNRRA Team 182 paired off daily in three groups. For instance, in Munich UNRRA workers discovered more than 50 small children in private homes or public buildings.33 The Feldafing camp housed 400 teens while in Traunstein 249 foreign children were on the road, at times with their teachers.34 These uprooted youngsters could be found everywhere, and they needed immediate aid.

The “International D.P. Children’s Center Kloster Indersdorf” Opens Its Doors

A mere fifteen kilometers from the recently liberated Dachau concentration camp in a small Bavarian village, UNRRA volunteers found the old convent Kloster Indersdorf35 on June 25, 1945. The centuries-old building, located in the Upper Bavarian market town of Indersdorf, had long been the diocesan and commercial center of what is today the county of Dachau. The founding of the original Augustinian monastery dates back to 1120. In the early nineteenth century the Community of Salesian Sisters had taken over the building and maintained a school for girls. From 1856 to 1938 the Sisters of Mercy of Saint Vincent de Paul had likewise cared for children and teens here until after more than eighty years, they had to vacate the building to make room for the National Socialist People’s Welfare (NSV) organization, more specifically the Bavarian Agency for the Homeless,36 which provided “compulsory care for homeless youths” until the end of the war.37 Only later did the UNRRA team gradually learn about the existence of an appalling children’s barracks adjacent to the convent wall, a so-called “Foster Home for Foreign Children,” in the last nine months of the war. The pleasant-sounding name had concealed an institution in which children of “foreign races” were systematically “fostered” to death.38 The National Socialist youth institution located in the convent had carried out the management of the barracks. At the directive of Heinrich Himmler, leader of the SS, female foreign forced laborers all over the German Reich had had to either give birth to their children at special maternity clinics or surrender their babies to the appropriate “foster home” immediately after birth. At the end of the war, surviving children of these local barracks were cared for by the Protestant Innere Mission, along with the remaining young inhabitants left in the convent.

From Team 182’s perspective the former convent had the basic equipment to open a children’s center quickly. Within days, the US Army took possession of the old building and handed it over to UNRRA Team 182 on July 7. Fifteen of the children who were already there simply remained because it was presumed they were foreign-born. Twenty more children whom the UNRRA team or the US Army had discovered in Munich would follow soon after.39

At first glance, the centuries-old convent had seemed appropriate as a refuge for children; up to twenty-five young people could be accommodated in dormitories with beds. There were leisure areas; a large, central, elegant baroque hall became the dining hall; two well-equipped kitchens were quite conveniently attached.

The “cloister”40 had a gymnasium, lavatories and workshops. It also had its own farm with 11 cows, some 30 pigs, 4 horses, about 240 hens, ample fields for crops, and well-kept vegetable and flower gardens, which suggested the residents would be able to at least partially supply their own food.41 A second glance, however, revealed the disadvantages of an ancient building: it had no hot running water, the large rooms were heated only with wood stoves, and the long corridors were uncomfortably drafty. Nonetheless, because hospitals and sanatoria for the wounded were overcrowded, the big building would have to do for the time being while better housing was sought.42

Aerial photo of Kloster Indersdorf in the 1950s.

Indersdorf was a pioneer project43 served by eleven and later seventeen highly motivated and dedicated UNRRA volunteers from all over the world.44 In December 1945 the international team consisted of fifteen people: American director Lillian D. Robbins, Belgian doctor Gaston M. Gérard, seven “Welfare Officers” Greta Fischer (Czechoslovakia), Helen Steiger (Switzerland), Catherine Tillman (USA), Edna Davis (Australia), Anna Marie Dewaal-Malefyt (the Netherlands), Marion E. Hutton (USA) and André Marx (Luxembourg), as well as American secretary Mary W. Taylor. Englishmen John Gower and Harry C. Parker were Supply and Warehouse Officers for the procurement and administration of supplies. Josef Conrady from Luxembourg served as head cook, and the two Frenchmen Gustave de Sile and Lucien Picou as drivers.45 The UNRRA workers wore uniforms of their respective countries with UNRRA lettering on the upper arm and a globe as the UNRRA insignia on their headgear.

The first director of UNRRA Team 182 was the experienced social worker Lillian D. Robbins. She was replaced in early 1946 by Canadian Jean Margaret Henshaw. Dr. Gaston Gérard took care of emergency treatment for new arrivals as well as routine health checks for every resident. Since Anna Marie de Waal-Malefyt had served in the war as a nurse, she could lend the doctor a helping hand, later joined by the French nurse Yvonne Menny.

UNRRA Team 182 served at Kloster Indersdorf from July 7, 1945 until the end of July 1946: (first row from left) Harry C. Parker, Greta Fischer, unidentified, Helen Steiger, Director Lillian D. Robbins, unidentified, André Marx, Marion E. Hutton. (second row from left) John Gower, Dr. Gaston Gérard, unidentified, Mary W. Taylor, unidentified and the two French drivers, Gustave de Sile and Lucien Picou.

A social worker’s duties included registering the children, looking after their physical and psychological well-being, seeing to their education, searching for family members and starting the immigration or repatriation process. None of the “welfare officers” were actually trained social workers and couldn’t anticipate what duties would fall to them. Only Greta Fischer had worked previously in London as a certified kindergarten teacher in a home for war-traumatized children. There she had become familiar with Anna Freud and the emergent field of children’s trauma therapy. As the main eyewitness of events, Greta Fischer wrote about the group: “We started with the United Nations team, … which were all professionals, professional people, I would say, very special people, each one in professional know-how and also in devotion, resourcefulness and commitment to the cause.”46 At first Marion E. Hutton was the Principal Welfare Officer, but later Greta Fischer and André Marx also received this title as a result of their accomplishments.

Many of the responsibilities were assigned ad hoc. Greta Fischer’s duties consisted at first of securing optimal care for the youngest victims, as well as training and supervising personnel. Starting in the fall of 1945, she became responsible for planning the entire program. Even though many of the UNRRA team members spoke several languages – Greta Fischer, for instance, spoke German, English, Czech, French and some Polish – basic communication was not always easy.

Owing to her excellent knowledge of foreign languages, the task of interviewing and registering newcomers fell to Swiss teacher Helen Steiger, who recorded every detail of their backgrounds and history of persecution and reported them to the UNRRA central tracing service in order to find any possible surviving relatives. André Marx was a Jewish survivor 47 who, along with Greta Fischer, was responsible for planning and overseeing the school curriculum. As a trained cantor he especially cultivated the Jewish traditions and celebrations. Many of the teens looked upon him as they would a rabbi. “He is the light of our ethical lives; for our education alone, he strives,” as one Jewish survivor rhymed about him.48

Edna Davis saw to physical welfare and hygiene. She undertook hiring seamstresses and a shoemaker to make suitable clothing and shoes as best they could and was also assigned to clothing distribution as well as English instruction. In the fall of 1945, Catherine Tillmann took charge of leisure activities.

All volunteers needed many skills. For instance, the cook was expected not only to provide meals for hundreds every day, but also to oversee the convent butcher shop and ensure that sufficient food provisions from the local farms were delivered to the kitchen daily. He was also expected to know about special dietary requirements. The two French drivers had not only to manage transports from the supply depots, but it was also helpful if they could repair vehicles or speak other languages.49 In September 1945, Mary Heaton Vorse, the renowned American journalist and activist for women’s and workers’ rights, assisted the UNRRA team in caring for the children and reported on the team’s work in American newspapers.50

To house the UNRRA personnel, the US Army requisitioned the finest houses in the village; some volunteers, however, like Greta Fischer, preferred to live in the cloister together with the young DPs they were caring for.

Helpers in the pioneer project

When opening the Children’s Center, the volunteers faced serious challenges. While the building was being cleaned and supplies stored, the first small children and youngsters had already arrived. On September 15, 1945, 192 boys and girls from 13 different nations, including 49 Jewish concentration camp survivors had already moved in.51 These children needed not only food, clothing, clean beds, warm baths and medical care, but also psychological counseling, education and leisure activities. Organizing all of this exceeded the resources of the eleven-member UNRRA team. Not until 1946 were other welfare agencies such as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJJDC) and the Jewish Agency able to supply assistance.

Mother Superior Dolorosa Mayer (in black) with the Sisters of Mercy of Saint Vincent de Paul, 1945.

After the war the Sisters of Mercy intended to return to Kloster Indersdorf and reclaim their religious community. However, their return took place under other conditions than they had hoped.52 By arrangement with the American occupation forces, the Sisters were to help the UNRRA team care for the uprooted children. After their seven-year absence the first Sisters returned on opening day, July 11, 1945, in their blue tunics and large white headpieces. The villagers and the UNRRA team greeted them warmly, and the nuns “… got along well with their American supervisors; however, they had difficulty identifying with the disorder and lack of manners prevalent in the children’s home.”53 The ten Sisters were put to work on the farm and in the kitchen, the laundry and the sewing workshop; as experienced nursery school teachers, Adelgunde Flierl and Audakta Huber were ideal for the little ones. The nuns were treated by the UNRRA team in a “friendly, helpful, tactful and courteous manner,”54 wrote head nun M. Dolorosa Mayer, who was in charge of household and personnel management. Her letters to their motherhouse in Munich describe the work: “We have to clean and set up the place as quickly as possible, but my hands are tied because I’m told to do too much at the same time. For example, we need to clean and furnish a huge area to store everything ordered for the house… . It’s not easy.”55 So soon after the war there were indeed supply shortages:

“Yesterday Sister M. Ado tackled a whole mountain of laundry. Unfortunately, the washing machines are broken. Not a single one can be used. It was really tedious. She had no soap, no brushes, and hardly any washing powder; and yet, she did it! As for Sister M. Audakta, she’s with the children. … Sister M. Adelgunde really had her hands full trying to get everything done that she’d been assigned. Yesterday, for instance, she had to deal with two whole truckloads of kitchen things, bedding and material; every day brings something similar.”56 The Sisters’ management of the center proved to be remarkably focused and energetic; the UNRRA team considered them a loyal and hard-working staff, as Greta Fischer noted forty years later, still full of praise: “The nuns [there] to help us were really wonderful people.”57

If the young survivors were to be well cared for, and especially in light of general scarcity, the center had to turn itself into a productive unit, a stressful and demanding task. The fields and vegetable gardens were still tended with the most primitive tools; pails were used to carry hot water for bathing and cleaning; the old wood and coal stoves had to be managed by hand. There was a shoe repair workshop for refurbishing children’s footwear, but there was a scarcity of leather for making new shoes. Children’s clothing had to be sewn from fabric, blankets or second-hand uniform components whenever they could be obtained. The center’s own butcher worked overtime slaughtering and preparing enough meat.

Of the earlier German personnel who had been employed at the previous Indersdorf children’s center, only one girl for the kitchen, a seamstress, a maid, and the secretary, Centa Probstmayr, would see their employment renewed. The latter had been working at the center since 1941 and at times had been solely responsible for managing the entire institution.

German workers keep house and do farm labor.

To overcome the lack of workers, in July 1945, 10 farm-hands, 6 gardeners, 5 seamstresses, 3 washerwomen, 8 kitchen helpers, 14 housemaids, a nurse, 3 nursing assistants, a guard, a handyman, 2 office staff and a custodian were hired.58

In July 1965 Greta Fischer moved permanently to Israel. There she was hired by Jerusalem’s Hadassah Hospital, the largest and most prominent in the nation, where she built up the Social Work Department and directed it until her retirement in 1980. As a faculty member at the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work, she helped prepare students for their future profession. Fischer was a doer; she saw to it that patients who were released from the hospital continued to receive care once they were at home. She set up a telephone hotline for cancer patients. She also founded “Melabev,” today the leading Israeli aid organization for dementia patients and their families; she initiated short-term care facilities and senior citizens’ clubs. Everywhere she inspired people to offer empathetic support to others. The prominence of social work in Israeli hospitals is her special legacy.658

The hiring of German personnel ensured the center’s economic functioning, but even more urgent was the question of care. Who could be entrusted with direct interaction with the youths? Understandably, this task could not be given to Germans.61 Yet members of UNRRA Team 182 were unable to master this immense assignment on their own. As a rule, those responsible for the children’s care worked in rotating shifts: two days from 7:00 a.m. until 7:00 p.m. followed by two days from 1:00 p.m. to 10:00 or 11:00 p.m. The goal of an eight-hour workday with one day off per week was never reached.62

Greta Fischer was often on duty day and night: “My memory goes back to many nights looking after 25-30 babies who demanded to be fed and comforted, trying to snatch a couple of hours of sleep in-between.”63 As increasing numbers of “unaccompanied children” arrived at Indersdorf, their numbers having reached more than 200 in the meantime, the striking lack of employees grew unbearable. Adult DPs were therefore tasked with helping the child survivors as house parents and teachers since they, too, had endured similar experiences, coming from the same cultures and speaking the same languages. The aim was to have one adult for five or six kids, “in order … that the children were cared for individually and could speak their own languages.”64

It wasn’t easy, however, to find qualified personnel in the ranks of the other DPs, quite simply because “many of the best professional leaders of the Allied countries [had] been exterminated.”65 Adult DPs were also in want of aid, had been marked by their own persecution or internment in camps and were emotionally unstable. Greta Fischer points out that they were often wholly consumed by their own repatriation issues, involved in political disputes or more interested in satisfying their own needs than in overseeing young people’s development. However, housing in bedrooms for two or three and payment in kind with cigarettes, chocolate, “fine soap” and clothing was enticing.66 After years of malnutrition, most grown-up DPs came to the center merely for the better care, or at least so it seemed to the Sisters of Mercy.67

In the meantime, 94 adult DPs had taken up residence in the house – a number far exceeding the guidelines issued by the UNRRA. In November 1945 an UNRRA screening team even came to the hard conclusion that not only did “a large percentage” of grown-up DPs offer “no value for the children,” but even worse, that “their presence disturbs the atmosphere in the home.”68 Some adult DPs therefore had to be sent away; others had their DP status revoked 69 while still others allowed themselves to be repatriated at a time when these individuals were still urgently needed in the Children’s Center.

Sister Adelgunde Flierl, UNRRA correspondent Mary Heaton Vorse and an adult DP (left) with infants in the center’s washroom.

Thus, again and again we find numerous reasons for the lack of reliable teachers as well as resident foster “parents.” What’s more, tensions between the foreign teenagers and German help made it hard to retain or hire German personnel, strains that even broke out in isolated incidents of violence. As a result, the situation found relief only once organizations like the international World ORT Union70 assisted with vocational training, or the Jewish Agency and the Polish and French Red Cross helped with drawing up departure paperwork for the respective countries. For example, Dr. Martha Branscombe from the US Committee for European Children was helpful in preparing orphans for immigration to the USA. 71

Displaced children arrive

By June 12, 1946, more than 6,000 foreign children, who were without parents or other relatives, had been registered in the US occupation zone. About 2,000 had been found by UNRRA search teams. The others had been discovered in DP camps together with adults or had been noticed by chance by the US Army or UNRRA because they huddled together in groups and generally appeared to be in a pitiful condition.

The Jewish displaced children lingering in the US occupation zone immediately after the war were mainly survivors of concentration camps. The majority of Gentile boys and girls had been forcibly displaced from Poland or Ukraine as forced laborers in Germany, although others had also suffered in concentration camps.

Among the Gentile displaced children, a distinction existed, however. In the western part of the US Zone there were mainly teenagers who, as a result of individual tragedies such as “accidental separation from the parent, death of the parent or abandonment,” had been housed in German establishments; in the eastern part, in Bavaria, large groups of children and youths were found who had been “violently removed from their homes” and “brought back from Eastern European countries.”72

Some teenagers, chiefly those from Upper Silesia or Slovakia, who proved to be more or less “Germanized,” had been forcibly removed from their homes and sent to institutions where no language other than German was permitted. In the Bavarian region around Regensburg, Traunstein and Straubing, a significant number of such Upper Silesian minors were found. Even if many of these children and teenagers considered themselves to be Germans, or in fact came from German Upper Silesian families, immediately after the war they had to pretend to be Polish or had to report violent treatment at German hands so that the Children’s Center could classify them as “Allied children” to be reunited with their families, as Upper Silesia had become a part of Poland again.

Because in summer of 1945 no one had any idea of how large the need was, UNRRA Team 182 was mandated to assist every non-German orphan found in the territory overseen by the UN. As a result, things got off to “an uncontrolled start,” when the heavy doors of the convent were thrown open to the displaced children in southern Germany.73

Between July 1945 and July 1946, at least 613 Jewish and Gentile child survivors were taken in and cared for at Kloster Indersdorf.

The numbers of foreign unaccompanied minors demanding admission to this initial reception center were high: “Since Monday children have been arriving daily. The first group consisted of 10 boys from 14-17 years, Hungarian Jews. That already sent us into shock. Then on Tuesday 25 Polish kids arrived, from tiny two-month-olds to two-year-olds and some girls and boys up to 16. On Wednesday, nine more little ones … and yesterday again seven bigger girls with scabies — totally neglected. I simply can’t see how we’re going to manage with 200 kids like that without the proper supervision and instruction. On the first day the boys had already taken the horses from the stable and [ridden] away. … Tomorrow 35 Poles are due to arrive; I think boys and girls.”74