22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

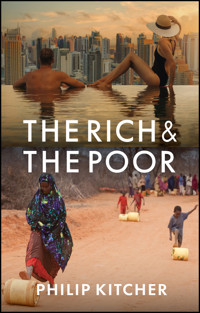

The Rich and the Poor is part chronicle, part analysis of a disturbing sea-change: the abandonment of ethics in public policy. Seventy years ago, it was possible for serious thinkers, including some in the governments of affluent nations, to consider policies for raising living standards worldwide. Today, by contrast, the principal policy questions revolve around how to stay on top in a dog-eat-dog world.

Philip Kitcher, one of the world’s most eminent philosophers, offers a new account of how ethics and politics should mix. The world needs to explore and reprioritize ethical questions, through inclusive deliberation that is both factually informed and mutually engaged with other perspectives. Achieving that end is hard, but without aspiring to it, we are likely to condemn our successors to lives of great hardship. Climate change demands global cooperation of a kind that can only be obtained by returning to ethical inquiry. The divorce between ethics and economics threatens disaster for all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 377

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Dedication

Title Page

Copyright Page

Quote

NOVEMBER 2024

Preface

Notes

1 The Erosion of Kindness

Notes

2 Rethinking Aid

Notes

3 Ethical Inquiry

Notes

4 The World is Out of Joint

Notes

5 Nothing to be Done?

Notes

Index

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1.1

Relative gain in real per capita income by global income level, 1988–2008...

Figure 1.2

Percentage of absolute gain in real per capita income received, by global income...

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

Dedication

For Ayşe Buğra and Osman Kavala,and in memory of Evelyn Fox Keller,three friends whose actions have constantly reassured methat compassion and courage are not extinct.

The Rich and the Poor

PHILIP KITCHER

polity

Copyright Page

Copyright © Philip Kitcher 2025

The right of Philip Kitcher to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2025 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

111 River Street

Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-6347-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024945216

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Quote

NOVEMBER 2024

O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this.

King Lear

The sea demands: reluctantly we give

a sliver of a cliff, a spit of sand.

Will paying willing tribute let us live

in greater safety on contracted land?

A cloud no bigger than a human hand

on the horizon – swells, turns grey, then black.

Ignored by those who chant “Consume! Expand!” –

they will not suffer from the tides’ attack.

Recruited by the press of urgent need,

new regiments of the dissatisfied

must supplicate in temples built by greed,

trusting that ostentation will provide.

The hurts we feel defeat our common sense.

Sclerotic policies denounce reform.

A world gone mad repudiates defense

to shield its children from the coming storm.

The sea demands: we fancy we have found

permanent refuge from its fiercest waves –

until our hard-earned legacies are drowned,

submerged forever in unquiet graves.

New York City

Preface

The seed from which this book has grown was planted in my young adulthood, half a century ago. It was embedded as I came to recognize how extraordinarily fortunate I had been. My life, I saw, was on track to be different from those of my parents, or indeed of any of my forebears. Unlike my father, who had left school at 12, or my mother, whose education had finished when she was 14, I had been able to attend one great university as an undergraduate, to receive a doctorate from another great university, and to have been given the opportunity of embarking on an academic career. Later, when I attempted to trace my ancestry further, I realized that the relatives I knew had been comparatively lucky. For their parents and grandparents had almost certainly been siphoned off into the workforce before they reached the age of 10, assigned to the exhausting low-paying jobs in which they would pass their lives, subservient to masters whose orders they must obey, and reprimanded whenever they were taken to have made an error. The men toiled as day laborers on richer men’s farms; the women were servants in the houses of the wealthy.

I had been born, I came to see, in one of the rare right places at one of the rare right times. After the Second World War, the Labour government, led by Clement Atlee, designed and set in place the British welfare state.1 As one small part of their achievement, local education authorities received funds to enable needy students to attend universities. In my case, given the low income of my parents, I was awarded a grant not only to pay the fees but also to cover the costs of daily life. It was sufficiently generous to allow me to send a little money home. Originally, though, when I had presented the form to my mother for her (necessary) signature, she had hesitated. Universities were not for “people like us.” With the education I had already received, I could “get a good job.” I could, for example, become an accountant or an actuary. It took some persuasion before the form was ready to submit.

For more than 20 years, the reforms providing increased opportunities to Britain’s poorer people were accepted by later governments, even when Conservatives were in power. Beginning around 1980, however, the generosity I had enjoyed began to be retracted. The policy of providing grants to needy students was abolished; it was one of the many victims of the 1990s assault on public goods. Part of my luck resulted from the electoral success temporarily enjoyed by a party genuinely concerned with opening possibilities to working people – and their children. Another part stemmed from a strange convergence between the sympathies of a Tudor monarch and the judgment of a primary school teacher.

Towards the end of his brief reign, Edward VI, the only male heir of Henry VIII, was moved by a sermon preached by Bishop Ridley (who would later be burned at the stake under orders from Edward’s sister – and successor – Mary). Shortly before the young king died, he signed the charter to create three institutions for the poor: Christ’s Hospital, Bridewell Hospital, and St Thomas’ Hospital. Only one of these (St Thomas’) is a hospital in the contemporary sense; the other two are schools, originally designed for housing and educating poor children.2 By the early twentieth century, Christ’s Hospital had moved out of London, and was open to children from all parts of the British Isles – provided that the family income was sufficiently low. (The ceiling in the mid-twentieth century was £1,000, roughly double what my parents earned in their best year.) It is a school with a distinguished history, and, during my boyhood, the boys’ school enjoyed one of the best academic records in the United Kingdom.

The school’s quality was well known in some educational circles. That knowledge prompted a master at St Mary’s school for boys, my local primary school in Eastbourne, to change my life. One afternoon in 1954, as school was ending, Mr. Manson, assigned to teach the 7-year-olds, took me aside. He asked me if my parents would be at home later – causing me to wonder, of course, what I might have done wrong. His intention, as I found out when he came, was not to report a misdemeanor. He wanted to tell my mother that he thought I would benefit from the fine education Christ’s Hospital offered. If I continued on the same trajectory, he explained, I might well succeed in the open entrance exam. His advice was absorbed and pondered. In due course, I applied, took the exam, and was admitted. In consequence I enjoyed an education of a sort I could only dream of for my children and can only dream of for my grandchildren.

My life, then, has been transformed by an odd conjunction of agents: a cluster of progressive politicians, a sensitive boy king, and an unusually thoughtful and kind schoolmaster. And, of course, by three magnificent educational institutions – Christ’s Hospital, Cambridge University, and Princeton University – that opened their doors to a serving-class boy.

*

During my career as a professor, spent teaching in American universities, the original sense of my good fortune has only increased. Moreover, as I have compared the opportunities for poor children in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s with those available to kids like me in the 1950s and 1960s, the rhetoric celebrating “the land of opportunity” has only come to appear more vacuous, more nonsensical, and more morally bankrupt. Since the 1980s, of course, the diminishing interest in funding public institutions, especially in programs to enlarge the fortunes of the poor, and the correlative hostility to taxing the rich, on both sides of the Atlantic, have led me to despair of the political condition of the two prosperous nations I know best. Elsewhere in the affluent world, the losses have been less. Vestiges of welfare states still survive. Yet, even in the places apparently most committed to the flourishing of all their citizens – the Nordic countries, for example – it is impossible not to observe a retreat. The army of disposable people is growing, just as the rich grow ever richer.

The repugnance I feel in contemplating the gap between the lives of the rich and the lives of the poor has bubbled away under the surface of my philosophical writing, even when I have been concerned with apparently unrelated topics. In criticizing human sociobiology (and later kindred ventures in evolutionary psychology), I was concerned to expose the flaws in claims that progressive attempts to enhance human opportunities would “rub against the grain of human nature.” My reflections on the uses of contemporary biomedicine concluded with a reminder that many human lives are limited not primarily by people’s genetic endowment but by the harmful environments in which they live: enthusiasm for molecular adjustments should be matched (or exceeded) by a resolution to provide access to medical care, to safe housing, and to schools in which children might learn. In considering the roles of scientific research in democratic society, I have emphasized the importance of attending to all people. My approach to ethics (presented in chapter 3) has opposed the thought of moral principles delivered from on high, commending instead inquiries that respond to the perspectives of all those affected by an issue. Most explicitly, in proposing that societies should rethink education, I have argued for programs that replace the vision of children as potential contributors to national wealth with emphasis on their development as individuals and as citizens who can cooperate for the common good.3

Themes that have been implicit before become explicit in the chapters that follow. I was led to be more forthright by a message from my undergraduate college, Christ’s College Cambridge. In January 2022, the eminent legal scholar, Jane Stapleton, then Master of the College, invited me to give the C. P. Snow Lecture during the academic year 2022–23. The series, honoring Snow, a former College Fellow, had enjoyed a distinguished succession of lecturers in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, before a roughly 10-year hiatus. I accepted eagerly, but felt a heavy responsibility – to prepare something worth hearing.

In considering a topic, I began in the obvious way, by returning to the Rede Lecture, delivered in Cambridge in 1959, with which Snow has been identified ever since. The first part of that lecture, in which Snow distinguished two cultures, one scientific and one humanistic, and went on to urge greater emphasis on science in British education, gave rise to heated debate. Yet when I reread the lecture, and pondered Snow’s retrospective reflections on it (available in the excellent edition edited by Stefan Collini4), I discovered something I had never previously noted. Snow identified his main thesis as developed in the second part of the lecture. Science should have greater prominence in the curriculum, he claimed, because the transformation in standards of living achieved in the affluent world through science-directed technology ought to be extended to the people of all nations. Closing the gap in the quality of lives between the rich and the poor was, for him, a morally and politically important task.

And in the world of the 1950s, in a country with a flourishing welfare state, none of his hearers dissented from that.

Fast forward to the present and the recent past. The part of the lecture that was once controversial is broadly accepted. Around the world, scientific education is viewed as the key to economic development, and therefore emphasized (to the extent that countries are able to do so). But the idea of a large-scale moral mission to give aid to those who have less – commonplace at a time when intra-national inequalities of opportunity were being diminished – has vanished from the contemporary scene. The burning policy questions for nations center on how to get ahead, or stay ahead, in a dog-eat-dog world. Productivity becomes everything. Social institutions, including the education of the young, are wrenched into a form geared to narrow economic success.

Recognizing this reversal, I found the theme for my lecture. What has happened? What gains and losses have been made? Who has benefited and who has lost? As I wrestled with these questions, I came to see an issue even larger than whether the rich have an obligation to aid the poor. For the decades between 1980 and the present have witnessed the withdrawal of ethics from policy decisions. Governments rarely ask what is right, but wonder what is expedient. If we are lucky, they ponder what is expedient for the nation; all too often, they focus on what is good for particular political careers. The large issue, then, concerns the place of ethics in politics. Oddly, my Snow Lecture inchoately juxtaposed two perspectives, those of the idealist who regards the neglect of ethical ideals as scandalous, and those of the realist who recommends that we figure out what works in the world we live in.

This book is my attempt to address the larger issue, using inequality within and among nations as my leading example.

*

I begin with a review of what has occurred. Since the 1980s, inequality among nations has decreased. At the same time, inequality within nations has typically increased, with the phenomenon especially marked in countries that have long been prosperous or that have recently joined the club of the relatively affluent. On their own, however, numbers do not tell the important part of the story. We need to understand what economic gains or losses mean with respect to the quality of the lives people live.

Gaining such understanding is begun at the end of chapter 1, and continued in chapter 2. Here, I take over (and develop in my own way) a framework for assessing the quality of lives (and thus of the need for aid) articulated by the economist/philosopher Amartya Sen and by the philosopher/legal scholar Martha Nussbaum. They focus on capabilities. Can a person find safe shelter, maintain health, become educated, be a member of a mutually supportive community, have genuine options for a life’s trajectory? In asking whether capabilities increase or decrease under economic change, we have a way of tracing the significance of what has happened.

Yet, when some gain and others lose, a measure of the consequences for individuals is not sufficient. We must ask if some redistribution is in order. The situation calls for ethical inquiry. How is such inquiry properly conducted? Chapter 3 proposes a methodology for investigating ethical questions. It centers on a special form of deliberation, one that includes representatives of all the people who are affected by the question, one that is factually well-informed, and in which each representative attempts to enter into the perspectives of each of the others, and to fashion an answer all can tolerate. Realists will protest that this is utopian. They are correct to do so. Nevertheless, in attempting to resolve ethical questions together, we should strive to embody the three virtues – being inclusive, well-informed and mutually engaged – to the greatest feasible extent.

In chapter 4, I use the frameworks presented in chapters 2 and 3 to evaluate the data reviewed in chapter 1. The retreat from considering ethical ideals in matters of policy turns out, unsurprisingly, to be an ethical catastrophe. Even people unmoved by that verdict (hardline political realists prominent among them) must recognize the consequences of the economic reshaping of the global social world. Climate change threatens to make life considerably harsher for those who will come after us, even for the children and grandchildren of many people living today. For nearly 40 years the problem has been recognized. Nonetheless, virtually nothing has been done. Moreover, nothing is likely to be done unless the nations of the world recognize the obstacles human inequality poses to any progress on the issue – and move to demolish them. The right thing turns out to be what is expedient – indeed, what the world urgently needs.

The final chapter considers whether there are any practically possible ways to reverse the ethical regression of the past decades. Although I outline some steps that could be taken, I am not optimistic. The best hope is that diagnosis, elaborated by writers and artists more gifted than I am, may serve as a wake-up call. Or, perhaps, that others will see options I have overlooked.

*

Along the way, I have been helped by many people. As I was crafting the lecture, Nancy Cartwright, Michela Massimi and Susan Neiman gave me perceptive feedback on early drafts, enabling me to improve the version I ultimately delivered. Lively discussion after the lecture not only encouraged me to think about developing further the central ideas, but also pointed me in valuable directions. I am particularly indebted to conversations with Duncan Bell and William Peterson, and to an email exchange with Partha Dasgupta. My first complete version of the whole book was read by four generous scholars, Paul Auerbach, Quassim Cassam, Angus Deaton, and Jan-Christoph Heilinger, all of whom have given me much advice and many suggestions that have enabled me to be clearer, more careful, and more accurate than I would otherwise have been. Julia Griffin has drawn my attention to unclarities in some of my formulations. I am also greatly indebted to two anonymous readers for their superbly thoughtful and constructive comments. Finally, I have benefited from a workshop, organized by Jan-Christoph Heilinger, at which I received many helpful suggestions that have helped me to do some fine-tuning.

In thinking about the questions I deal with, I owe much to two colleagues at Columbia. During two decades I co-taught the senior seminar in Economics and Philosophy, first with Ronald Findlay and then with Dan O’Flaherty. I have learned much from these two outstanding economists, and I hope they enjoyed our weekly exchanges as much as I did. An even older debt is to a long-standing friend, Michael Rothschild, with whom I have discussed issues in economics over nearly three decades.

It has been a pleasure working with a legendary editor, Ian Malcolm. His early enthusiasm for this project encouraged me to think that my lecture might become a useful book. He has constantly drawn my attention to sources I might have overlooked, and pointed me towards questions I might have bypassed. I am immensely grateful to him.

Finally, as always, I thank Patricia Kitcher for her support, her detailed suggestions and her practical wisdom.

*

The book is dedicated to three people in whom I have seen the exemplification of its message. In 2011–12, Ayşe Buğra and I were Fellows together at the Wissenschaftskolleg in Berlin. Our many conversations ranged over a number of disciplines, and I learned much from her expertise in social theory. Ideas from those discussions have seeped into the pages that follow. Through her I also met her husband, Osman Kavala, a philanthropist who supported local programs in arts and culture accessible to all people as a means of self-expression and mutual understanding. Today he has become even more famous, as an example of the repressive policies of the Erdoğan regime. Initially arrested over four years ago, he was acquitted when the case against him came to trial, only to be re-arrested on his way out of the courtroom. Autocrats rarely make the same mistake twice. Erdoğan was careful to ensure that the judge presiding over the next trial would be one who would deliver the “correct” verdict. Osman remains in a Turkish prison. Meanwhile, Ayşe’s own freedom is periodically in jeopardy.

My late friend and co-author, Evelyn Fox Keller, is the third dedicatee. She was not vulnerable to punitive actions from her government. The United States has not yet become an autocracy. Her life, too, was directed towards expanding the opportunities for disadvantaged and marginalized people. Despite the hostility sometimes directed towards her within the academy, she was constant in pursuing her ideals, however unpopular that pursuit might make her. Her legacy, in the understanding of science and society, and in the articulation of a rightly influential feminist perspective, is rich and enduring.

When I left Christ’s Hospital in 1966, I heard the words always uttered at the leaving ceremony. Like generations of other leavers before us and after us, we were enjoined to remember the benefits our education had conferred upon us – “from those to whom much has been given, much will be required.” That formula is not a veiled pitch to make donations to the school. Rather, it commands us to make use of our education for the wider good. We must give something back.

Although they were not given the admonition I received, none of Ayşe, Osman, and Evelyn have shirked that task. All three have felt compassion for the poor and the downtrodden. All three have worked, in different ways, to alleviate their plight. All three have been prepared to pay the costs.

The world has been kinder to me than to these three friends of mine. But I would like to think that this book, in a far slighter way, is part of my own efforts to “give something back.”

Notes

1

For a perceptive historical analysis of the considerations leading to the welfare state, see Tony Judt,

Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945

, London: Heinemann, 2005, especially the chapter “The Rehabilitation of Europe”.

2

Christ’s Hospital served as a school from the beginning. Bridewell Hospital originally discharged two unrelated functions: one part of Bridewell Palace was used as a place where “disorderly women” were disciplined; the remainder provided housing for homeless children. It later evolved into a school, and, after moving to Surrey, is now known as King Edward’s School.

3

For the critique of human sociobiology, see

Vaulting Ambition: Sociobiology and the Quest for Human Nature

, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985; for biomedicine, see

The Lives to Come: The Genetic Revolution and Human Possibilities

, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996, especially the final chapter, “An Unequal Inheritance”; for science and democracy, see

Science, Truth and Democracy

, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, and

Science in a Democratic Society

, Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2011; for ethics, see

The Ethical Project

, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2011, and

Moral Progress

, New York: Oxford University Press, 2021; for education, see

The Main Enterprise of the World: Rethinking Education

, New York: Oxford University Press, 2022.

4

C. P. Snow,

The Two Cultures

, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

1The Erosion of Kindness

Public lectures typically have an ephemeral impact. Even when they are delivered by well-known experts, whose rhetorical skills capture the audience for an hour or so, the effect usually fades quickly. Occasionally, however, things go differently. A speaker touches a nerve. A new question is posed and gives rise to impassioned debate. Discussion continues for decades. Half a century on, there are retrospective analyses, attempting to fathom the central significance of what was said. In extreme cases, the lecturer may come to be defined by the occasion, known principally as the person who said that then, rather than by whatever accomplishments generated the invitation to speak in the first place.

This scenario unfolded over the latter half of the twentieth century, beginning in 1959. C. P. Snow – recently knighted and later to receive a peerage – delivered the Rede Lecture in Cambridge.1 Sir Charles Snow had been a research scientist, though not a particularly successful one. He had also written a series of popular novels. His knighthood had been conferred primarily because of his work during the Second World War, when he had served as a civil servant, responsible for coordinating scientific contributions to the war effort. He had discharged this important task in ways that elicited admiration and gratitude. Standing at the podium of the University Senate House, he could be seen as representing both the sciences (primarily because of his administrative achievements) and literature (although, as some critics would already have pointed out, he had not written any “serious literature”).

The full title of Snow’s lecture was “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.” In virtually all subsequent discussions, including Snow’s own, the title was abbreviated.2 It became simply “The Two Cultures.” The shift reflected the heated debate ignited by his remarks. The first part of his presentation portrayed intellectual life as an arena containing two distinct and mutually uncomprehending cultures. One of these, the “scientific culture,” received a largely sympathetic treatment. Its rival, the “literary culture,” was depicted more harshly, characterized as irrelevant, reactionary, elitist or worse. Unsurprisingly, some humanists took up arms against Snow’s contrastive judgment, viewing it as based on vulgar, Philistine misunderstandings. None did so with more fury than the Cambridge literary critic, F. R. Leavis, whose polemics had an intensity (and, some said, even a breach of good manners) that inspired commentators to talk of the “Leavis–Snow debate.”3

Four years later, Snow published his own afterthoughts. He reflected on the reactions to “The Two Cultures,” expressing one regret. He had originally intended, he announced, to call his Rede Lecture “The Rich and the Poor.”4 He now wished that he had stuck to that original decision. For, in retrospect, he lamented the neglect of the second part of his lecture. The more important theme, he claimed, was his attempt at “sharpening the concern of rich and privileged societies for those less lucky.”5 That theme had been untouched by the furor he had provoked. In effect, he was declaring that the torrid controversy had bypassed his most significant point.

In that debate, a favorite phrase of Snow’s had inspired mockery from some of his detractors. “Scientists,” he had told his audience, “have the future in their bones.”6 Whatever the merits of the metaphor, it served as a pivot for connecting ideas about culture and education to the theme of global inequality in wealth. The phrase captured Snow’s enthusiasm about what he called a “Scientific Revolution.”7 The episode he had in mind was not the one given that name by historians of science, when they reflect on (or wonder about) the birth of modern science in the seventeenth century. Snow focused on a more recent development, occurring in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, through which scientific knowledge had been harnessed to direct technology.8 On his interpretation, that revolution had already transformed the lives of citizens in affluent nations, and the task he envisaged for the future was to extend the process, improving human life world-wide. The project of extension, morally required and also, he supposed, politically inevitable, would call for people thoroughly trained in the sciences, especially in their applied branches.9 The close of his lecture expressed his concern that Britain’s educational system, hidebound and handicapped by a “literary culture,” was inadequate. His country could not play its proper part in an important enterprise.

Snow’s worries on this score were not focused quite as narrowly as my summary may suggest. His concern with Britain’s potential shortfall in discharging a moral duty, was accompanied by an anxiety; he shared a post-war sense of belonging to a once-great country, now searching for a new role on the global stage. Cold war politics prompted him to envisage a struggle for winning the hearts of the world’s developing nations. Waged between the Soviet bloc and the West, it would require troops to be recruited from the member states. If the United Kingdom failed to amend its anachronistic educational system, its contributions would be negligible, and its status accordingly reduced. Britain would become “an enclavein a different world,” and, if the Soviets were to capitalize on their early lead in the appropriate type of education, it would be “the enclave of an enclave.”10

Although, as it seems, the lecture was originally intended to deliver a moral message, it ended by intertwining moral and political considerations.

*

That is not the way we live now. Subsequent history has falsified Snow’s predicted future. No large political movement, whether exporting science-based technology or proceeding independently of it, seeks to spread wealth from the affluent world to poorer nations.11 To cite one obvious symptom of “realistic” indifference (one to which I shall return), the poorer nations of the world, vulnerable to the effects of climate change, plead again and again for support to mitigate the effects of the changed atmosphere generated from the emissions through which other countries have gained their wealth; at best, their pleas are answered with grudging donations of ludicrously inadequate size. Snow’s focal question, “How can we decrease global inequality?,” does not guide policy in the fashion he and his contemporaries believed it should. Governments today ask a different question. Not “Can our nation play a role in human progress?” but “How can we continue to compete in a global economy?” Intellectuals and policymakers of the 1950s and 1960s would view that change as a disastrous moral lapse. As do I.

The retreat from recognizing a duty to decrease poverty in distant places is accompanied by an abstinence from charity closer to home. Within nations once committed to expanding opportunities for their poorer citizens – and apparently with enough resources to carry out that commitment – programs once hailed for the social good they generated have been scrapped. Ambitious attempts to enable all citizens to maintain their health have been diluted through underfunding. Public housing is scaled back, forcing large numbers of people to participate in housing markets largely uninterested in meeting their needs. Homelessness increases. For those barely able to scrape together enough cash to pay the rent, the only affordable accommodation is often dangerous and unhealthy. Schools are starved of the resources they need, and millions of children attend institutions staffed by a rotating corps of overworked and underpaid teachers. Food banks are the only source of sustenance for many families. In a country once proud of its welfare state, there are now more food banks than there are public libraries.12

Sixty-five years after Snow’s lecture, the transition he celebrated in the affluent world is a thing of the past. With its passing, come a host of blighted opportunities. So many lives narrowed and damaged because the public institutions that used to expand horizons have been allowed to decay, or, in many instances, have been intentionally and savagely destroyed.

To repeat: Snow’s auditors, as well as most of their contemporaries, would see what has happened as an ethical catastrophe. For most contemporary policymakers and politicians, however, these developments represent social progress. In their view, we have rightly abandoned vainglorious attempts to realize unattainable ideals. We have learned to be realists, doing what we can to promote ethically appropriate goals. It is, of course, regrettable, that nothing more can be done for the people whose lives excite the sympathies of soft-hearted idealists: for the homeless; the families dependent on food banks (and their unlucky relatives who have no food banks to supply the nutrition they need); for the children who attend decaying and dangerous schools, and are taught, in too large numbers, by overstressed and poorly trained teachers; for the many poor people who cannot take the steps to preserve their sight and hearing, who cannot afford the medicines for the disease conditions that affect them; for the young whose best career option is a life of crime; and for the victims whose only housing options are in places where such careers are pursued. But we should realize that these are the unfortunate side effects of the best overall policies. Think of them as unavoidable collateral damage.

Two contrary ethical judgments: which, if either, is correct? This book tries to answer that question. It must begin, of course, with a serious attempt to review what has occurred, not just in a small sample of places, but globally. My first aim, then, is to try to understand the effects of the changes in policymaking, not simply in the spare economic terms in which they are typically presented – a table of crude figures about average income, here, there, and everywhere – but recognizing the impacts on people’s lives. The precise reports of economic gains and losses are a helpful beginning (to be explored later in this chapter). But they must be supplemented by relating them to the quality of human lives. That task, begun in the present chapter and continued in the next, will lead us to focus on opportunities, on what people are able to do, on what matters in human lives. We shall find, as we might expect, that there are winners and losers. The question – to which Snow and his contemporaries assumed an idealistic answer – becomes one of deciding what forms of redistribution, if any, are ethically required of us.

Yet there is a larger issue, one that must be addressed if the investigation undertaken here is to succeed. Behind the contrary ethical judgments lie two radically different stances with respect to ethics and politics. Idealists are troubled by the neglect of the poor, because they view social policies as properly shaped by attempts to follow an ethical principle. Realists, on the other hand, accuse such efforts of overlooking constraints, and thus producing ethically worse outcomes than might have been achieved.

Thus, this book, like Snow’s lecture, will be concerned with the opposition between two perspectives – or, if you like, between “two cultures.” They are not, of course, the pair whose merits Snow’s supporters and his opponents debated. According to one, political realism, it is naïve and dangerous to think that moral ideals can ever dictate policy. Instead, our moral precepts must be adapted to the realities of the situation. According to the other, moral idealism, important moral principles cannot be overridden, subordinated to considerations about the context in which they should be applied. Where realists view sophisticated politics as rightly responsive to features of the world limiting the direct realization of a moral ideal – and thereby, perhaps, expressing a deeper moral commitment – idealists see these allegedly more mature judgments as abandoning moral duties.

The contrast I have just drawn helps in orienting us as we engage with the larger question. It is too stark, however. Many political realists are by no means impervious to the force of moral ideals. They worry, however, about the tendency to demand their implementation, come what may. We should, they believe, always be wary in case the circumstances are unfavorable for the application. When that is the case, devotion to the ideal is likely to cause considerable harm. The moral upshot of idealist insistence turns out to be much worse than policies based on limiting the ideal – or even disregarding it entirely. Adopting this stance can easily harden into habitual suspicion. Political realism then comes to insist on evidence for taking pursuit of the ideal to be unproblematic. Attempts to realize a moral ideal are suspect until proven innocent.

Although they are often portrayed as starry-eyed dreamers, bewitched by illusions of impossible utopias, many moral idealists are far from naïve. They agree about the relevance of the actual circumstances. For them, however, the burden of proof lies on political realists. The strategy of trying to implement the ideal is a good default option. Trying to act in accordance with an ideal is taken to be benign until the shortcomings of the venture are shown. Hard-bitten realists, as idealists see them, acquiesce too easily in thinking of a course of action as hopeless. Their suspicions lead them to settle for inferior options – indeed, often for policies that allow many human lives to wither. They give up trying, assuming, almost automatically, that anything better is impossible. Moreover, those who quickly espouse a “realistic” solution to a problem are often comfortably situated. They are not those who suffer from the policy they favor – and they may even benefit from its pursuit.13

The opposition that concerns me is simpler and more familiar than a controversy often pursued by political philosophers, in which self-styled realists debate with proponents of ideal theory, posing general questions about the nature and scope of politics.14 My interest lies in understanding the role moral considerations (ideals or principles) should play in specific policy decisions. The political realists who interest me include many non-philosophical folk, people who worry about particular well-intentioned efforts they see as likely to end up doing more harm than good. The moral idealists who oppose them decry a complacent acceptance of alleged constraints, campaigning for social change to promote a worthy cause.

Conflicts of this type are hardly esoteric. They often erupt before a large public. In what follows, we shall not need to venture into territory explored by a sophisticated and interesting branch of political philosophy. We shall, however, need a more refined understanding of the everyday opposition between realists and idealists. For the standard way of characterizing the controversies is to ask whether a principle both sides accept can be compromised. As we shall see, in chapter 3, this way of framing familiar debates misconstrues the ethical project and its applications to political life. I shall attempt to correct the misconception by viewing the disagreement as one to be settled through ethical inquiry. By focusing on methods for ethical investigation, controversies apparently headed for stalemate – or, more typically, won because realists are the ones in power – can be resolved. Moreover, some of the resolutions will provide moral idealists with everything they want.

Snow figures as an – unreformed – moral idealist. He took a principle for granted, seeing it as brooking no exceptions. The rich nations of the world have the obligation to spread their wealth and their expertise to aid the poor. He also believed firmly in the possibility, indeed in the inevitability, of attaining the goal demanded by the obligation. So too did his hearers and readers: there was no controversy over the second part of his lecture. That absence of a reaction expresses the spirit of an age. During the decades immediately after the Second World War, not only Snow, not only Cambridge academics, but even governments accepted the idea of framing policy to shrink the gap between the rich and the poor.

They were, I claim, right to do so. I suspect, however, that the basis for their judgment was dogmatic acceptance of an unrestricted principle. Moral idealists can do better. As later chapters will try to show, their debates with realists don’t have to end with shouting and stamping of feet. I am a reformed moral idealist. But in accepting the resolution of the debate my unreformed predecessors announced, I give the process that has led to substituting issues about national productivity for questions about transnational aid a pejorative name: during my lifetime, I have witnessed “the erosion of kindness.”15 That process is part of a wider habitual tendency towards “realism,” one that has effectively marginalized ethics in debates about economic and political decisions. My task in what follows is to explain what has occurred, to show how regressive it has been, and thus to argue for a change of direction. Reformed moral idealists, I might say, “have the future in their bones.”

*

Ironically, with respect to educational policy, the politicians and pundits of today tend to agree with Snow’s call for reform. Around the globe, in a majority of nations (although not in all16), children must be trained so as to deliver the goods. A cluster of subjects is given priority. We must produce more scientists, technologists, engineers, and mathematicians. Not because they are to be sent out as missionaries, to lend a hand to the hitherto benighted, bringing cutting-edge technology to every part of the world. Snow’s idealistic vision gives way to a sober appreciation of the economic realities. Barack Obama’s emphasis on STEM subjects was motivated by America’s need to remain economically competitive (or should it be “dominant”?). Other, less idealistic, leaders have recommended more radical surgery. Margaret Thatcher’s vision of education recognized the necessity of a broader collection of “practical” subjects: applied economics, business, finance, graphic design, advertising, fashion, and so forth. These subjects were unavailable in the universities Snow knew – and even later during my own higher education. In some places, they have displaced options on the menu from which students in the 1960s and early 1970s could choose.

Leavis would be further incensed by this trend. But Snow? Would his approval of the celebration of STEM transfer to the Thatcherite expansion? The question is unanswerable. What is clear, however, is a shift in points of comparison. No longer would he be concerned with the differences among the UK, the USA, and the USSR. Instead, I imagine him wondering why other nations have not emulated South Korea, building campuses like that of Seoul National University with its huge complexes of buildings dedicated to highly specialized applied sciences; and with its small enclave in which the humanities are housed.

The Rede Lecture has triumphed in its first, initially controversial, educational theme. It has failed dismally in its second, in the confident claim about the spread of technology and of wealth around the globe. The thoughts for which Snow was often vilified have won the day; those then viewed as uncontroversial, and retrospectively seen by him as most important, have been decisively defeated. Why did his predictions on this score go awry?

One of his milder humanist critics, Lionel Trilling, offered a perceptive criticism. “The Two Cultures” neglected politics.17 The significance of the point was revealed by later developments. What Thatcher appreciated, and what Snow missed, was that knowledge does not automatically flow wherever it might be needed, to be translated into the benefits it potentially provides.18