13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

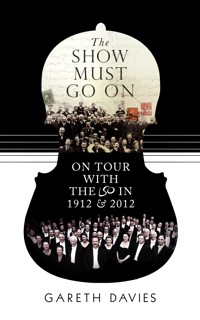

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A memoir of the London Symphony Orchestra on tour in the US and beyond, focusing on their historical first visit to America in 1912 when they were due to sail on the Titanic, and their most recent travels. Gareth Davies, Principal Flautist at the LSO, tells the remarkable story of a groundbreaking expedition through recently discovered diaries, archive material from London and New York and newspaper reports from the time. Against this is set a behind-the-scenes account of the LSO's worldwide touring schedule, which finds that a surprising number of the same challenges remain. We join Gareth and his colleagues as they contend with airports, volcanoes, travel strikes, illness and even life and death situations. As well as vivid descriptions of sitting centre stage surrounded by music and working with Haitink, Gergiev and Sir Colin Davis, we get to glimpse into the backstage goings on and see inside the mind of a professional musician as never before. Written by someone at the centre of the action, we follow the travels of two musicians, a century apart in the same orchestra. The show does go on.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 343

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

THE SHOW MUST GO ON

THE SHOW MUST GO ON

On tour with the LSO in 1912 and 2012

Gareth Davies

Frontispiece images:

Top: Members of the LSO aboard the liner Baltic, 1912.

Bottom: Valery Gergiev conducts the LSO in Japan, 2012.

First published 2013 by

Elliott and Thompson Limited

27 John Street, London WC1N 2BX

www.eandtbooks.com

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-90873-981-0

Text © Gareth Davies 2013

The Author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

All photography in the book is reproduced by kind permission of the author and the London Symphony Orchestra.

Cover image and image on rear endpapers: the London Symphony Orchestra at its London home, the Barbican. Photo: LSO/Alberto Venzago.

The LSO logo is used by kind permission of the London Symphony Orchestra.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover design: kid-ethic.com

Typesetting: Louis Mackay / www.louismackaydesign.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

1. 1912: Upbeat Before the Downbeat

2. 2012: International Commuters

3. 1912: Travel Arrangements

4. 2012: A Long Way From Home

5. 1912: The Men and Woman of the London Symphony Orchestra

6. 2012: Planes, Trains, and Automobiles (and Bicycles, and Running)

7. 1912: The First Concerts

8. 1912: First Impressions

9. 2012: America

10. 1912: A Party in Boston?

11. 2012: The Universal Language of Mankind

12. 1912: Arthur Nikisch: 12 October 1855 – 23 January 1922

13. 2012: Conducting a Conversation

14. 1912: A Plague of Locusts

15. 2012: FAME

16. 1912: Bad News

17. 2012: The Show Must Go On

18. 1912: Almost There

1912 London Symphony Orchestra

2012 London Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra, Conducted by Arthur Nikisch, Tour to USA and Canada 1912

Acknowledgements

Index

For Mum and Dad. For giving me words and music

Introduction

Every musician I know has a tale to tell of life on the road. As in any oral tradition, facts become blurred, names confused and words embellished or lost; but every now and again, someone will recount a story full of detail, as clear as when it took place … because they were there.

There are two parallel histories of the London Symphony Orchestra. The official version begins in 1904 and continues, uninterrupted, to this day. Alongside it runs another version, a secret history of players’ memories and experiences – some of which have been shared along the way, others kept hidden from view, and a very few put down on paper.

In 2007 I started writing a blog for the LSO whenever we went on tour. My posts there served as a record of the orchestra’s life during our travels around the globe. As the years passed, describing concert after concert became more challenging, and the entries gradually became a record of my own experiences and memories: my history of the orchestra.

The LSO archives hold evidence of many important moments in the orchestra’s history, but one event that still captures the imagination and has passed into LSO folklore is the 1912 trip to America (when, the story goes, the players nearly set sail on the Titanic). They were the first European orchestra to undertake a journey across the Atlantic, and there must have been so many stories to tell from that trip – all, it was assumed for decades, lost in time.

However, two years ago I had a chance conversation with our archivist Libby Rice which unexpectedly opened a door to the past. The few sketchy details we had about the 1912 tour were mainly press reports and administrative documents – the official version. What we didn’t have were the tall tales and memories of our musical ancestors, how they felt discovering the New World, what they thought of the concerts, what they ate … and that, incredibly, was what had suddenly come into Libby’s hands. A package had arrived at the LSO office from Roberta Gagliani, who had been clearing out her great-aunt’s attic and discovered some of her grandfather’s possessions. Among these was a small pocket notebook which mentioned the LSO. Realizing its significance, Roberta sent it to Libby.

Pages from Charles Turner’s 1912 diary, mentioning the Titanic.

The notebook belonged to LSO timpani player Charles Turner, and chronicled his experiences during that 1912 tour to North America. Incredibly, a few weeks later we were contacted by Jack Nisbet, who sent us a copy of a diary written by his grandfather, flautist Henry Nisbet, during the same period.

Overnight, many of the questions I had were answered, gaps in our knowledge filled; through Turner’s and Nisbet’s words, we had a glimpse into what life was like for them on the road exactly one hundred years ago. Some of the stories that had been presumed lost were sitting on the page in front of me.

Two things struck me as I went through the diaries: how much has changed, and how much remains the same. It was then that the idea for this book entered my head. I had originally intended it to be an extended blog entry, but as my research drew me in and more information came to light and the project got bigger, the parallels between the LSO in 1912 and in 2012 became more pronounced, and I just kept on writing. Each chapter in the book about 1912 is followed by a chapter about 2012. As the story from last century revealed itself, the narrative naturally fell into themes: travel, conductors, discovering new places, being away from home and, finally, dealing with life and death.

The book will introduce you to the players of 1912, and to the musicians I work with every day in 2012; to legendary conductor Arthur Nikisch and to our current principal conductor, the mesmeric Valery Gergiev. We will travel from London to Japan, China, most of Europe and, importantly, New York City, exactly one hundred years after the orchestra’s first visit. I hope it gives you a unique insight into what makes an orchestra tick, but also what it’s really like to be a musician travelling with one of the world’s greatest orchestras. The travel arrangements and working hours have changed, but many things haven’t – not least, the kind of individual who decides to become an orchestral musician. This is the story of the London Symphony Orchestra in the words of the players themselves: three musicians, one orchestra, a century apart.

1

Upbeat Before the Downbeat

1912

It’s 1.30 p.m. on Thursday 28th March, 1912. Euston Station is unusually crowded as the one hundred musicians of the London Symphony Orchestra stand around saying their goodbyes to friends and family before embarking on a historic tour to the United States of America.

No European orchestra has ever travelled across the Atlantic before, and this departure is the beginning of an adventure that has been two years in the planning. The newspapers in London and New York have been full of articles publicizing the tour, pictures of the conductor Arthur Nikisch have been plastered on the front page of the New York Times, and gossip columns have whispered about his alleged fee of $1,000 a night. The headline in an article published in New York on that day boldly describes the tour as ‘An American Conquest’ and even the King himself has given it his seal of approval. For a fledgling orchestra, born out of rebellion only eight years earlier, it is an early statement of intent that the LSO is forging its own path; it is a young, ambitious newcomer. Sit down, be quiet, and listen.

Souvenir programme from the 1912 American tour.

Sir Thomas Beecham had planned to take the Queen’s Hall Orchestra to America a few years before – plans that came to nothing – and perhaps it was his failure that galvanized the board of directors at the time to make sure the LSO made the first move. However, the name of the London Symphony Orchestra on its own was not enough. In the last few months before commercial recording of the symphonic repertoire really took off, only people who had travelled had heard the legendary ensembles of central Europe, and the mythology of these great performers loomed large in people’s minds. The Berlin Philharmonic, Leipzig Gewandhaus and America’s own Boston Symphony Orchestra were the Holy Grail for an orchestral enthusiast. However, surely this dynamic ensemble with an already turbulent history was going to be welcomed in the land of the free.

From his offices on 42nd Street, the New York-based promoter Howard Pew had been bringing musical acts of varying sorts to American audiences since 1885. He had had great success persuading Presidents Harrison and McKinley to allow him to take the US Marine Band around the country, as well as bringing a host of Italian opera stars to sing for the eager American public. A long-held dream of his was to bring a premier European ensemble across. Nobody had done it before, and he was a man with a shrewd business sense as well as high artistic standards, so the LSO was not his first point of call in 1910. He knew that to sell tickets and encourage other rich benefactors to help him make it happen he needed a big name on the rostrum; and so, before he could decide on an ensemble, the first piece of the jigsaw was to secure the services of the conductor Arthur Nikisch.

Nikisch was revered in America, thanks to his highly successful tenure as principal conductor with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. His performances were still being talked about 19 years later, especially as he hadn’t returned to the USA; audiences were desperate to see him again. Before the advent of the jet-setting conductor, audiences had to wait a long time between appearances, which only increased the mystique surrounding Nikisch and consequently his draw at the box office. The combination of high artistic standards and box office receipts was what attracted Pew.

From the outset, Nikisch made it clear that he was interested in coming on one condition: that he could bring the orchestra of his choice. Knowing that it would always be the conductor rather than the orchestra that would sell tickets, and also aware that Nikisch would hardly agree to come all the way back to the States with a second-rate band, Pew agreed immediately. Nikisch then proudly announced that the only orchestra he would consider accompanying across the Atlantic was the London Symphony Orchestra.

Pew must have been delighted. He knew that bringing Nikisch back for a triumphant return was going to generate huge press interest. It would also attract some of the musically-minded philanthropists he had in mind to help pay for the small matter of bringing an entire orchestra and their instruments across the sea, not to mention insuring their instruments and paying for food, hotels, travel, and music hire. The costs were going to be high, the risks even higher; everything had to be right for the tour to be a success. However, as Henry Kniebel wrote in the New York Tribune in 1912 shortly before the tour began:

In the highest form of instrumental art, as in the hybrid form of opera which chiefly lives on in affectation and fad, it is the singer and not the song that challenges attention from the multitude. We used to have prima donnas in New York whose names on a program ensured financial success for the performance … for prima donna … read conductor, and a parallel is established in orchestral art which is even more humiliating than that pervading our opera house.

Kniebel’s disapproving remarks suggested a future in which a new world of superstar conductors travelled the globe, commanding adoration and large fees: exactly what Pew wanted. Negotiations began.

As plans progressed for the 1912 tour, LSO managing director Thomas Busby realized that if it was to become a reality, financial support would be needed – preferably from both sides of the Atlantic. Howard Pew was constantly sending letters to the board of the LSO about ways to keep down costs, which were beginning to spiral out of control owing to the sheer scale of the tour. At a meeting, the orchestra had agreed to the trip and sent a list of requirements to Pew. He was to provide

All meals, three a day and accommodation in which not more than two should occupy a room. Mr Pew should provide a capable baggage and instrument porter in addition to the LSO porter and that $20,000 to be deposited with Brown and Shipley and Co. prior to the departure from England.

Ultimately, most of these demands were met, but in a more creative way than perhaps the board had imagined. Accommodation was indeed provided, a hotel in New York being the first port of call; although, as Charles Turner reveals in his 1912 diary, this was not quite what they were expecting: ‘Go to Hotel Victoria, Broadway. A giant place but more trouble. They have put 3 or 4 beds in one room. Large, beautiful rooms but the fellows don’t like it. Beautiful lunch anyhow at 12 o’clock.’

The player-to-room ratio was not as per the contract (although a stationary hotel was a temporary measure in any case), but at least Turner’s lunch was satisfactory. After leaving New York on April 9th, the players would not sleep in a hotel room again until the end of their trip, on April 28th. To save costs whilst still keeping his end of the agreement, Howard Pew had come up with the idea of sending the orchestra around America on a specially chartered train. The fly in the ointment was that the players’ accommodation during the trip would consist solely of several shared sleeping cars on the train. Turner’s diary reveals that immediately after most concerts the band would trudge back to their train, drink, smoke, and play cards until the early morning, and then catch a little sleep in their bunks. This was not the accommodation they might have hoped for, but then, as now, in the arts world, every penny counted.

At a board meeting in November 1911, Thomas Busby had presented a piece of paper that would be of great help in securing funding for the tour. He had come directly from a meeting at Buckingham Palace, where he had asked the King to consider giving his patronage to the LSO, pointing out that this would greatly benefit the special relationship between Britain and America. There was an ulterior motive to his request, in that 18 members of the LSO were also members of the King’s Private Band, and as such were contracted to be available to perform at the palace at all times. Many were key players, and so by gaining the King’s patronage, Busby ensured that these players would be released to play in the concert tour. There was one small condition: all 18 members were required to wear three King’s Medals at every engagement in America, so that members of the public could pick them out from the rest of the orchestra. Busby and Pew must have been delighted; the letter from the King was proudly displayed at the front of the souvenir programme.

In one of the many pre-tour articles that appeared in the American press, Busby, when asked about the repertoire for the tour, declined to reveal it, but boasted that the audience was in for a treat and a surprise. The truth was that there were huge arguments going on between Pew and the LSO board about what should be played, and who should pay for it. Busby therefore had no clear idea of the intended programme.

In a 1911 board meeting, a letter from Pew was read out in which he complained that he ‘didn’t see why he should share in the royalty charged for the Richard Strauss works’. One reason why the LSO thought that he should pay was that he had requested that they play Strauss in the first place. The board had come up with a series of programmes that was at first rejected on the basis that, with so much travelling, it would be better to concentrate on two or three programmes and repeat them around the country, thereby saving on rehearsal time and costs. At this time, the orchestra was associated with the music of Sir Edward Elgar, and the board was keen to programme some of his works; however, Howard Pew’s representative in London – a Mr Blumenburg – made his feelings clear on the matter at a meeting in July 1911:

Mr Blumenburg was dissatisfied with the programme as arranged and [said] that more Brahms, Strauss, Mozart and Bach music should be included and that if any Elgar items were included he would fire the whole scheme up as far as he was concerned.

Busby was asked at the same meeting to draw up some new programmes fairly swiftly, with no Elgar.

Once the patronage of the King had been secured, funding and sponsorship from sources on both sides of the Atlantic followed. Towards the end of 1911, the musical instrument manufacturers Boosey and Hawkes offered to donate trumpets, horns, and trombones to the orchestra with the proviso that the players actually played on them throughout the tour, which seemed a reasonable request. A financial compromise was made that required the musicians themselves to insure their own instruments, something that Busby boasted in the New York Times made the value of $500,000 the ‘most valuable set of instruments ever to make the journey across by boat’. No publicity opportunity was missed. Finally, Howard Pew managed to secure a private donor whose patronage and substantial investment would make the whole trip possible, in the form of one Warren Fales.

The letter from Buckingham Palace confirming the King’s patronage.

Warren R. Fales of Providence, Rhode Island, was well known across the country as a patron of good music. He claimed to own the biggest manufacturing plant in the world, making machinery for the cotton mills. As a result, he was very wealthy indeed, and spent a lot of his free time and money on the arts. He was conductor of the American Brass Band of Providence, which was a famous ensemble at the time and claimed to have the ‘most notable bass drum in the USA’. Very well travelled in Europe, he even boasted of having made a complete circuit of the globe several times.

One thing is certain. The LSO would not have been able to make the trip if it hadn’t been for the financial help Fales provided. Howard Pew had the ideas; Fales the money to realize them.

2

International Commuters

2012

Super Mario goes to Sonic City

After our first concert in Osaka, we all piled onto a bullet train, which is always one of the highlights of touring Japan. Unlike the trains on which I am normally incarcerated, these ones are fast and clean, leave on time, and look cool. The efficiency with which everything runs in Japan extends to the railways, and to keep to their tight schedule there is a time limit for the opening of the doors. When you get on or off a bullet train there’s a sort of high-pitched electronic whistle, and a very twitchy guard stands and waves a torch down the platform to signal that it’s time to shut the doors and move off. There is a guard on every door, whereas in Britain we have one guard for every train – strikes, leaves, and weather permitting.

You can imagine that for a two-week tour of the London Symphony Orchestra, suitcases are on the large side. So that we don’t bring the Japanese transport system to its knees, our cases are transported for us on a separate truck, leaving us relatively unencumbered and ready for the frantic race that is disembarking. On the first day we arrived it was chucking it down with rain, prompting many of us to buy cheap umbrellas. The only ones we could easily find were old-fashioned long umbrellas, the kind British businessmen used to swing briskly on their way to work in the days when everyone dressed as an extra from Mary Poppins. Because of this, we were a large group of Westerners all looking terribly English indeed. All we needed was a copy of the Financial Times under our arms and the cliché would have been complete.

The train pulled into the station, with most of the orchestra poised to get off as quickly as possible. The doors opened and we jumped off one by one, opening our automatic umbrellas with a click, whump sound. The scene was reminiscent of a parachute regiment being flung out of a plane. We leapt onto the platform as the guard was gradually becoming frantic: his door was obviously going to be the last to give the green light in the chain of command. All the other guards along the platform were giving him evil looks. He started to sweat and shout. This would normally have been the point at which Sue Mallet, our director of planning, joined in with the shouting until the guard was shocked into submission. However, she was in London, and this tour was being run by Mario de Sa, our tour manager and one of the coolest customers there is. He often greeted us in the morning with a cheery ‘Morning, chaps!’ I expect in a former life he was a pipe-smoking World War II fighter pilot and a thoroughly good egg.

Mario remained calm under the increasing pressure being exerted by the guard. The high-pitched whistling was replaced with a lower beeping noise, sending the guard into a silent rage; perhaps we were affecting his targets for the week. Realizing that the doors were soon to shut, Mario raised his long umbrella and, without taking his eyes off the guard, smilingly jammed the end of it into the door’s way, preventing it from closing. It began beeping more loudly. The last of the jumpers appeared on the platform, and Mario leaned forward and looked into the carriage, which was empty apart from a shocked-looking elderly couple wondering what had happened to their normally prompt and reliable train service. Just as the guard spotted the umbrella jammed in the door, Mario removed it with another smile and said, ‘Thank you very much.’ The door closed, relieved, and the train moved off one minute late. Mario ran to the front of the group, holding his umbrella up. ‘This way, chaps!’

We were in Omiya, at the fantastically named Sonic City, to play Mussorgsky/Ravel, Pictures at an Exhibition. I hate this piece. I don’t really know why. Maybe it’s because I’ve played it in so many education concerts in my time, or outdoors in fields. I often find it a bitty piece – lots of disjointed pictures – and it’s tricky to play. I should have seen it coming, of course: Valery Gergiev, our principal conductor, started pulling it to pieces in the rehearsal just before the concert. He wanted more extremes of dynamics and sound, more theatre, more effort in general.

Nigel Thomas (timpani) and Sharon Williams (piccolo) get some rest on a train somewhere in Japan.

As Phil Cobb, our principal trumpet, threw the opening volley out into the hall, the majestic sound of the LSO brass filled the room, but there was no pause between pictures for Valery as he plunged straight into the low, aggressive burble of ‘Gnomus’. I saw a lady in the front row jump in her seat. Valery has the ability to pluck details from the music that no one else seems to pick up on; almost as if he has access to a different score from everyone else. He takes well-known pieces and breathes new life into them. The pauses in this movement were long and ominous before Lorenzo Iosco’s sinuous bass clarinet gurgled around the bass section. But it was ‘Baba Yaga’ that took my breath away.

I have become used to playing ‘Baba Yaga’ in Discovery concerts for eight-year-olds at which, during the pause bars, a presenter on stage talks, describing the terrifying image of a hut on chicken’s legs going round eating kids. They always seem to conclude by saying, ‘… and he swallowed the children: yum, yum.’ I suppose we don’t want to send the kids home scared, but this has spoiled the piece somewhat for me. Until, that is, Valery launched into the most awesome, abrasive version I have ever heard. There was no need for talking: the full might of the orchestra screamed from the stage and grabbed people from their seats, rendering ‘Baba Yaga’ truly nightmare-inducing. As we finally reached the ‘Great Gate of Kiev’, the whole orchestra was in full flight, and it was over all too quickly.

On the train back, we boarded in record time, and Super Mario relaxed as we left Sonic City behind. I sat down next to my friend Chi-Yu Mo, a clarinet player.

‘I normally hate that piece.’

‘Me too.’

‘It was awesome.’

‘Yum, yum.’

Quite.

The long haul

On my suburban train last week, I read in the Metro free newspaper an extraordinarily in-depth article claiming that if you spend two hours of each working day commuting, by the end of your working life you will have spent twelve years of your life sitting on a train. Or, in my case, standing up.

It struck me that as LSO players, we often spend significantly more time than this ‘commuting’ to various places around the globe. This week, for instance, we are spending more than 24 hours in transit. This is not unusual for us, but does mean that if you spend your entire working life with the orchestra (I joined when I was 28, and am now older), you will spend something like 20 years commuting.

It is a measure of what an odd existence life in an orchestra can be. We are currently on the second day of a trip to Spain and Portugal. Yesterday I got up at 5.30 a.m. and drove to Stansted Airport, caught a flight to Valencia, had a bite to eat, then went to a rehearsal and concert. I crawled into bed at about 1 a.m. We played Schubert 5 and Bruckner 7; or was it Bruckner 5 and Schubert 7? I forget …

The hall in Valencia is one of my favourites: it has a very good sound, and you are surrounded by the audience. It almost feels like playing in the round, which can be unnerving if something goes wrong. However, with Sir Colin Davis wielding the baton we are in very safe hands. I love playing Bruckner 7 with him. In such a huge work, you really need a conductor who understands the overall architecture of the piece, otherwise it can end up sounding like a long line of unrelated chunks of sound. Sir Colin keeps the music flowing, and doesn’t let the long melodies wallow around. When we do slow down at an important climax – such as where the cymbals and triangle make their only appearance, in the slow movement – it makes a huge impact. By the end of the symphony I always have a sense of the long, arching journey we have made from start to finish. Last night’s audience certainly agreed, as Sir Colin was called back on four times.

Tonight in Lisbon we are performing Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and Bruckner 6. (Interesting that Bruckner’s 9th was unfinished, but is never called ‘the unfinished’. I suspect this may be because, even in this state, it is over an hour long. Bruckner’s ‘thank goodness it’s unfinished’ symphony, maybe?) I shall leave you with a mathematical observation.

The Metro piece suggests that you spend twelve years of your life commuting if you travel two hours a day. Sir Colin Davis is 80, and probably travels many more miles than the average commuter. As his working life is already far longer than most normal men, by my calculations, he will soon have ‘commuted’ for almost 120 years.

This either means my maths isn’t what it used to be, or – just maybe – the newspaper article has some slightly inaccurate figures. I know: it shocked me, too.

The Italian job

London’s black cabs have rescued me from certain lateness on many occasions. As someone who usually walks or rides a Brompton bike, it’s only when things are desperate that I get into a cab. It gives me a feeling of self-importance to jump in the back and say ‘Barbican Centre, please, and don’t spare the horses!’ I wonder whether anyone ever asks cab drivers to take the scenic route?

As you probably know, black-cab drivers have to pass an exam for which they must memorize all the street names in the city and be able to navigate them successfully. This is called ‘The Knowledge’. It is astonishing how much information they manage to retain about the muddled street system, while still leaving room for unique opinions on important world matters, usually involving Boris Johnson, the cost of the Olympics in 2012, and the dregs of society (otherwise known as cyclists). Sort-of-joking aside, it’s easy to take for granted the good things on your own doorstep. As I type this, my knuckles are still white with fear after gripping my seat very tightly indeed during a taxi ride in Turin.

On Friday we arrived in Pisa to kick off this Italian tour, and what a beautiful place it is. The famous tower seems to lean much more than pictures suggest, and the surrounding buildings are breathtaking in their beauty. It was hot in the Duomo for the concert, and guest leader Andrew Haveron’s Lark Ascending soared beautifully around the wooden ceiling, enjoying some much-missed summer warmth. Yesterday, a Saturday, we were greeted with a train strike and had to endure a very long coach journey to Milan, where the audience was appreciative. Playing Mozart and Beethoven with Sir Colin conducting continues to be one of my greatest pleasures in the LSO; he makes it so much fun.

After the concert we took buses to our hotel in Turin, arriving at about 2.30 a.m. A very long day indeed. The hotel is a huge building that used to be the Fiat factory. If you’ve seen the film The Italian Job – the original one with Michael Caine, set in Italy, not the American remake – it features heavily. There is a famous scene in which three Minis are driven through the factory and up onto the rooftop test track. This really did exist and, I suppose, honed the drivers’ skills somewhat, as it is a very long way down if you skid off. These days it is the hotel jogging track, complete with banked corners. I went up there this morning and there were two blokes running round making car revving noises. As well as the race-track scene, you may recall the fantastic stunt driving through the streets, pavements, and shopping arcades of Turin, where the Minis are driven down steps and through shops at breakneck speed. I can’t help thinking that whilst London cab drivers spend a couple of years going around London on a moped with an A–Z learning their craft, the cab driver I had last night simply watched the Italian Job driving sequences and was promptly handed his keys. I’m not sure whether he did actually mount the pavement, as everything was too blurred. When he heard my accent he locked the doors, looked at me in the rear-view mirror, started whistling ‘The Self-Preservation Society’, and took off. It was truly terrifying.

We have a concert this evening in the hall inside the factory building: a fantastic hall, with a very reverberant acoustic. I listened to the rehearsal of Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 4, as I don’t play in the piece. The hall allows the quiet passages to float effortlessly towards the back, and the loud moments rock the foundations. It should be a great evening: a great hall, great music, and I can’t think of a better conductor to lead us in this repertoire.

As the orchestra attacked the final forte chord of the symphony, Colin raised his eyebrows and looked taken aback at the sheer level of sound. He turned to the auditorium, seemingly watching the sound echo around the hall, then turned back to the orchestra and said something that made them all laugh. I couldn’t hear it from where I was sitting, but I have a sneaking suspicion it was ‘You were only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!’

Far, far, far, far East

I think someone has moved Japan since I was last here.

It’s taken us such a long time to get here, it’s the only explanation I can come up with. I left home at midday on Monday, and finally got into bed in Sapporo at midnight on Wednesday. Even taking into account that Japan is nine hours ahead of London, that’s one hell of a long time: about 28 hours of travelling. For those of you who travel business class and sit on twelve-hour flights there: well, if you carry on walking for another 50 metres, you’ll reach cattle class, where all of us sit. Evidently the music business doesn’t qualify. It’s a bit cramped, to be honest, and even someone as short as me finds it a squeeze for that long. On this occasion we arrived at Osaka airport, where the efficiency of the staff meant that (unlike at Heathrow) we were through immigration and baggage in about 20 minutes. Unfortunately we then had to wait another six hours for our flight to Sapporo.

I have never been so bored in my life. It was Chi’s birthday, but no matter how many times we wished him many happy returns, no matter how many free drinks he was given, no matter how many cards he received, we couldn’t get away from the fact that today, his birthday, was rubbish. To make matters worse, the orchestra had been split into two groups, and the other group left London after us and arrived in Sapporo before us. There was a secret ballot, so I’m told – so secret, in fact, that nobody knows who did it. Maybe I should start being nice to Sue Mallet again.

Rehearsal in Japan.

When we finally arrived at Sapporo airport, we faced an hour-and-a-half bus journey to the hotel. I could resist sleep no longer, and finally drifted off. When we pulled up outside the hotel I could see the other half of the orchestra in the bar opposite, eating and drinking and trying really hard not to look smug. They were totally unsuccessful. I piled straight in for some food and beer until I lost the ability to talk, which made some people very happy, then collapsed into bed and slept heavily.

We had a free day on Wednesday, and went to a volcano. It hasn’t erupted for a while (and didn’t when we went), but it was free to get in, so I didn’t complain. It was very nice to walk around after being stuck on public transport for a few days. Once again, I slept well last night, unusually for me in Japan.

Today we started the musical part of our tour. At the rehearsal, the band and Valery sounded and looked a little sleepy. He asked us to save our energy for the concert, which we did. The people I work with never cease to amaze me: we all got changed, Gergiev walked on stage, and the orchestra played as if its life depended on it. I was only in Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet in the second half, but the audience demanded an encore. We played the March from The Love for Three Oranges, an excellent encore, loud and short! Tomorrow the tour starts in earnest. We leave early and go hell for leather for the next week, with a concert every day. We have to fly from the North Island to the South Island. Let’s hope they haven’t moved that, too.

This way, this way, that way, this way, this way or that way …

I am writing this whilst travelling unbelievably smoothly and quickly on the Shinkansen train to Tokyo. You probably know it best as the bullet train, and it certainly lives up to its name. Its aerodynamically shaped front end looks like the love child of a train, a space shuttle, and a mutant duck, and when it shoots through the station at full speed the sense of harnessed power is awesome.

Today, we are on the 9.26 train. The carriages are double deckers, and we are on the lower deck, so the eye level from our seats is level with the platform, giving me a great vantage point from which to study Japanese footwear. The train is clean, all the toilets work, and the staff are polite. As we pull out of the station we accelerate at incredible speed, and everything becomes a blur apart from the mountain ranges and Mount Fuji in the distance.

This is my sixth visit to Japan. Every time I come, I am astonished by the efficiency with which it is run: the trains are on time, everything is clean, and the concert halls – even in out-of-the-way places – are spectacular. When I was lost at the station earlier in the week a young lady from the railway company asked me in perfect English if I needed help, and then proceeded to help me buy the correct ticket, take me to the platform, and make sure I was sitting in the right seat. As someone accustomed to the begrudging, monosyllabic grunting that passes for customer service in Britain, I was quite astonished.

The people who shepherd us round Japan are from the Kajimoto concert management company. If they were allowed to run countries, I am convinced they would end world hunger in a flash (although they would probably be more precise than me, and end it on a Monday at 9.23 a.m. GMT). From the moment we arrived, greeted by a smiling face and an LSO sign pointing us in the right direction, we have been looked after like royalty. In Sapporo earlier this week, we actually had to walk from the hotel to the concert hall unaided – but to prevent us getting lost on the way, one of our guides sat in the hotel foyer and showed us which door to go out of (there are two doors, you see). I walked a few yards to the edge of the hotel grounds and found an LSO logo on the lamppost with an arrow pointing left. I turned left. As I did so, I could see the next LSO sign on the next lamppost: it pointed straight on. I went straight on. When I reached this sign I began to panic – it was a pedestrian crossing which I had to negotiate on my own – but, fortunately, I could see another LSO logo across the road. I crossed. This next sign had the logo, and two arrows, one pointing left and the other pointing straight ahead but saying ‘slippery way’. Faced with this sudden test of initiative, I decided to live dangerously and go the slippery way. It was indeed slippery. At the end of this road was – you get the idea – a sign with the logo, telling me to turn left. I could see the hall now. When I reached the stage door there was another sign telling me to go in, and even more signs inside showed me where the dressing rooms, stage, and toilets were. By the time I had finished my walk to the hall, my eyes were exhausted.

The journey took three minutes.

Earlier this week, one of my friends left his mobile phone on a train seat. Back home, you would have simply cancelled the number and replaced the handset, as the chances of it being recovered were slim. On our return journey we went to the information office and filled in a form, not really certain that it was the right one. It took us an hour to get back to the hotel, and on our return there was a message at reception. The lost phone had been picked up, handed in, and would be delivered to the hotel at 10.30 the following morning unless we needed it earlier, in which case they could bring it over straight away. I expect they’d topped up his credit too.

When we arrived at our hotel yesterday another of our tour managers, Miriam Loeben, was presented with a letter from the previous hotel which consisted of a list of items accidentally left behind by members of the orchestra. The summary gives an idea of the attention to detail that’s typical of this country.

Left Articles in LSO Rooms

One jacket

Five coins

One Eurostar ticket (used)

One paper cup

One cleaning cloth

One nightgown from unknown room, cleared up with sheets by mistake

What a brilliant place this is!