Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

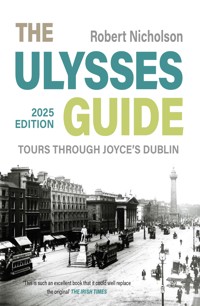

The Ulysses Guide: Tours Through Joyce's Dublin is an essential resource for readers of James Joyce's Ulysses. Following the novel's eighteen episodes through their original locations, it recreates the Dublin of 1904 against the backdrop of today's streetscape. First published in 1988 and updated here for 2025 to reflect new Joycean research and changes that have taken place in the continued evolution of Dublin city, The Ulysses Guide is a beloved companion to Joyce's masterpiece and a classic of Irish literary criticism.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 290

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Robert Nicholson was born and lives in Dublin. He studied English Language and Literature at Trinity College, and became curator of the James Joyce Museum at the Joyce Tower in Sandycove in 1978. He was also appointed curator of the Dublin Writers Museum in Parnell Square in 1991, and retired from both positions in 2019. The Ulysses Guide was first published in 1988, establishing him as an authority on the locations of Joyce’s novel, and in 2007 he wrote and presented a DVD for Arts Magic, James Joyce’s Dublin: The Ulysses Tour. He is co-author with Vivien Igoe of Tales from the Tower: A Personal History of the James Joyce Tower and Museum by its Curators (Martello, 2023). He is a founder member of the James Joyce Cultural Centre as well as a former chairman of the James Joyce Institute of Ireland. He is a regular contributor to The James Joyce Broadsheet.

The Ulysses Guide

Tours through Joyce’s Dublin

2025 Edition

Robert Nicholson

The Ulysses Guide

First published 1988

This edition published 2025 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

newisland.ie

Copyright © Robert Nicholson, 1988, 2025

The right of Robert Nicholson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-83594-016-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-83594-032-7

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Product safety queries can be addressed to New Island Books at the above postal address or at [email protected].

Set in 11 on 14.25 pt in Garamond

Typeset by JVR Creative India

Cover design by New Island Books

Cover image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Introduction to the 2025 Edition

Ulysses: The Episodes

Tour 1Telemachus, Nestor

Tour 2Nausikaa, Proteus, Hades, Wandering Rocks (vii, iv)

Tour 3Calypso, Ithaca, Penelope, Wandering Rocks (iii, i, ii)

Tour 4Circe, Eumaeus, (Ithaca), Lotuseaters, Wandering Rocks (xvii), Oxen of the Sun

Tour 5Wandering Rocks (xv, ix, xvi, x, xiii, xi, xiv, viii), Sirens

Tour 6Aeolus, Laestrygonians, Scylla and Charybdis, Wandering Rocks (vi, v, xviii)

Tour 7Wandering Rocks (xix) – The Viceregal Cavalcade

Tour 8Wandering Rocks (xii), Cyclops

Notes

Appendix I The Movements of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus on 16 June 1904

Appendix IIUlysses: The Corrected Text

Appendix III Joyce’s Schema and the Episode Titles

Appendix IV Stephen’s Morning Itinerary

Bibliography

Index

List of Illustrations

1. Sandycove Point

2. Sandycove Point in 1904 (Joyce Tower/Bord Fáilte)

3. The Star of the Sea Church, Sandymount

4. Irishtown Road

5. The Crampton Memorial (Dublin Civic Museum)

6. Glasnevin Cemetery

7. The Mater Hospital, Eccles Street

8. St Francis Xavier’s Church

9. Aldborough House

10. The O’Brien Institute

11. Amiens Street Station

12. Tyrone Street (Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland)

13. Beresford Place

14. Eden Quay and Butt Bridge

15. Brady’s Cottages (Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland)

16. St Andrew’s Church

17. The National Maternity Hospital, Holles Street (Nat. Maternity Hospital)

18. City Hall

19. Eustace Street

20. Grattan Bridge

21. The Chapterhouse of St Mary’s Abbey (Dúchas/The Heritage Service)

22. O’Connell Street (formerly Sackville Street)

23. O’Connell Bridge

24. Westmoreland Street

25. College Green

26. Grafton Street

27. Parkgate

28. The Four Courts

29. Foster Place

30. James’s Street (Guinness Brewery Museum)

31. Barney Kiernan’s (Dublin Civic Museum)

Photographs, except where otherwise stated, are reproduced by courtesy of the National Library of Ireland from the Lawrence, Eason and Keogh Collections. The maps were drawn by Neil Hyslop.

A Note on the Maps

For the sake of clarity, only the most useful and essential details are included on the maps. The reader may find it helpful to study an Ordnance Survey street map of Dublin for additional information on street names and peripheral detail. The principal route on each map is indicated with a bold line, while a broken line signifies a detour or link route. Alternate arrows pointing in opposite directions indicate that this part of the route is retraced in reverse.

Acknowledgements

No work relating the action of Ulysses to its locations can be complete without reference to Clive Hart and Leo Knuth’s excellent Topographical Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses, which identifies all addresses mentioned in the book and supplies some useful comment on the timing of each chapter. In 2004 this enormously helpful work reappeared in a new and improved form, compiled by Clive Hart and Ian Gunn with Harald Beck, under the title James Joyce’s Dublin: A Topographical Guide to the Dublin of James Joyce (published by Thames & Hudson). I am indebted to the many new insights and information provided by this book, and also to the past few years of contributions and discussions by its authors and the various other members of the ‘Ulysses for Experts’ web group. Further useful information has emerged from the Irish national census for 1901 and 1911, placed online by the National Archives and available to all at www.census.nationalarchives.ie, and from James Joyce Online Notes, edited by Harald Beck and John Simpson at www.jjon.org. Other sources are listed in the bibliography.

For permission to reproduce photographs from the invaluable Lawrence Collection in the National Photographic Archive, I am grateful to the Trustees of the National Library of Ireland.

My particular thanks are due to the late Patrick Johnston, Curator of the Dublin Civic Museum, to Peter Walsh, formerly Curator of the Guinness Brewery Museum, and to Con Brogan in the Photographic Unit of Dúchas, the Heritage Service, for photographs and valuable information; to Des Gunning and his successors in the James Joyce Cultural Centre, for helpful research; to Gerard O’Flaherty, Vincent Deane and other members of the James Joyce Institute of Ireland, for points of information; to the Photographic Department, Bord Fáilte, for assistance; and to my colleagues in Dublin Tourism for help of various kinds.

Citations from Ulysses are according to the critically edited reading text, © Hans Walter Gabler, 1984.

Introduction to the 2025 Edition

The Guide

When James Joyce wrote Ulysses, he did so with a copy of Thom’s Dublin Directory beside him and a precise idea in his head of the location of every action described in the book. The city of Dublin, more than any scholarly work of reference, is the most valuable document we have to help us appreciate the intricate craftsmanship of Ulysses. To follow the steps of Leopold Bloom, Stephen Dedalus and their fellow Dubliners from one landmark to the next has become an act, not merely of study, but of homage. It is, in effect, a sort of pilgrimage.

This guide is intended to enable pilgrims, be they scholars, students or ordinary readers, to follow the action of Ulysses as near as possible to the locations in which it is set. To facilitate the traveller it is arranged on an area-by-area basis rather than taking the episodes in sequence. The eight itineraries, which vary in length from one to two hours, occasionally overlap, and indications are given of how to link one route with others nearby. All are designed to be followed on foot except those of the funeral procession (Tour 2) and the viceregal cavalcade (Tour 7). Some of them begin or end conveniently near to a DART station. At certain points detours or extensions are suggested to places of Joycean or general interest. Followers of this guide now have further means of exploring Joyce’s metropolis. The introduction and spread of the dublinbikes rental scheme gives travellers the opportunity to pick up a pair of wheels at stations throughout the city centre and follow some of the longer routes without wearing out shoe leather or being swept off course in motor traffic. For those immobilised or abroad, or confirmed desk potatoes, there is now the option of Google Street View, which has recently been extended to most of the streets in Dublin (but not so far to all of the itineraries described in Ulysses). And even without such technical assistance, this book may still help readers with the visualisation of the time and space within which Joyce’s characters move.

Incorporated in the guide is an outline of the action of Ulysses as it is presented in each episode. It concentrates on the activities and movements of the characters throughout the day that is described (as distinct from memories, imaginings and ideas) and is, of course, intended neither as a substitute for, nor as an interpretation of, Ulysses itself. Page numbers, given in this ebook edition as digits in superscript within the text, refer to the standard Corrected Text of Ulysses (see Appendix II), but the guide may be followed using any edition of the novel.

There are many popular misconceptions about Ulysses, one of them being that the book describes a walk by Leopold Bloom which can be followed continuously from one chapter to the next like some sort of tourist trail. Bloom’s day is no stroll. He covers a total of about eight miles on foot and a further ten by tram, train and horse-drawn vehicle. Of certain periods of the day there is no definite account at all, and much occurs between chapters which is simply not described. The guide fills in these gaps as far as possible, and a table is appended charting the known movements of Bloom and Stephen over the course of the day.

Finally, there is one puzzle in Ulysses which this guide makes no attempt to solve, namely how to ‘cross Dublin without passing a pub’. Maybe you will be in one when you read this.

The Changing City

Since 1904 (and even since 1988 when this guide first appeared) Dublin has altered considerably. Buildings have gone, streets have been renamed, and shops and businesses continue to change hands. Some – but only a part – of this transformation is due to the destruction caused by the Easter Rising of 1916, the War of Independence which followed, and the Civil War of 1922–3. The ravages of these events were confined to certain streets and public buildings, some of which have been restored to their original appearance. Much more widespread is the effect of the gradual removal of old houses, sometimes piecemeal and sometimes by entire blocks, which has been taking place increasingly – and especially during the booms of the 1960s and the 1990s – to make way for new property development. Many old buildings which have been preserved have also been freshened up and deprived of the shabbiness which was characteristic of Joyce’s Dublin. The Celtic Tiger years strewed the city with spectacular buildings and ambitious developments, many of them in the docklands area (hailed, incidentally, as ‘the new Bloomusalem’ by Taoiseach Charles Haughey at the opening of the International Financial Services Centre). The crash which followed, and the impact of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, led to changes and closures.

In Bloom’s time the streets were laid with cobbles or setts; main thoroughfares had tram-tracks, standards and overhead cables; motor cars were a rarity (only one appears in Ulysses) and most people walked, cycled or took the tram. Without the roar and fumes of present-day motor traffic, it was possible to converse in the street as so many of Joyce’s characters do, and to cross the roadway at any point without the benefit of traffic lights. Horse-drawn vehicles, however, were plentiful, and the streets were presumably foul with dung, except at the established crossings, where a line of granite setts would be kept clean by sweepers. Dublin was lit by gas; façades were not obscured by plastic and neon signs; there were no television aerials. Shopfronts were more discreet, less flashy; most shops had awnings to shade them from the sun. Most of the city’s fine stone buildings were blackened and grimy with coal smoke. Without trees, traffic islands or painted lines, Dublin’s wide streets appeared even wider. Plastic bags and bottles, parking meters, traffic notices, drink cans, bilingual street signs and burglar alarms were other unknowns.

Letter boxes were red, bearing the royal cipher VR or EviiR; now painted green, some of these older boxes may still be found here and there in Dublin. Coins of the period, particularly the large copper pennies, were still in circulation up to decimalisation in 1971 – twelve pence to the shilling, twenty shillings to the pound. The guinea, worth twenty-one shillings, was a unit frequently used for fees and prices. The pound disappeared from the Irish purse in 2002 at a rate of one euro and twenty-seven cent.

Number 7 Eccles Street has gone, and so have the Freeman’s Journal office and Bella Cohen’s brothel. Much, however, remains – the banks, the public buildings, all the churches and nearly all the pubs mentioned in Ulysses are still there. While some of the Joycean locations have succumbed to the march of progress, others have managed to retain their identity, and there are even examples of resurrection. Sweny’s pharmacy has survived closure and is preserved as a Joycean landmark. Barney Kiernan’s, formerly a fading memory, has regained something of its original appearance, and trams are running again in Dublin. Many of the original buildings have altered little, despite changes of ownership. Businesses move or disappear so frequently nowadays that street numbers are included in many of the addresses given in the Guide to aid identification.

It is easy to fall into the nostalgic trap of thinking of ‘Joyce’s Dublin’ as a city in a golden age – a time of sepia photographs, parasols, penny tram fares and the leisurely clop of horses’ hooves. What we rarely see in the old photographs are the barefoot children, the rampancy of tuberculosis and rickets, the squalor of tenement life and the infamous brothels of Nighttown. Standards of hygiene and personal cleanliness were lower. The shirt which Bloom wears throughout that hot day under his black waistcoat and funeral suit will probably be worn again the next day with the cuffs turned over and a clean detachable collar. Public toilets were of the most rudimentary kind and were not provided for women. Though the poor and the intoxicated are always with us, they were there even more in Bloom’s day. ‘Dear, dirty Dublin’ was the provincial capital of a neglected country, and if independence, prosperity and cosmopolitanism have changed it, it is not altogether for the worse.

Reading Ulysses and exploring Dublin are two forms of the same process. Even as a confirmed resident of both the book and the city I make daily discoveries about each of them, in the most familiar passages as well as those that remain labyrinthine and challenging. If Dublin is no longer structurally the city that I knew at the beginning, so too Ulysses now seems to be different as more of it becomes apparent, and with every new reading it takes on a new complexion. I am grateful to the companions, both on the pavement and the page, who have supported me in my explorations, and I am grateful to New Island for the excuse and the encouragement to go out and do it all again.

Those who read Ulysses will know that Joyce was recording not merely the Dublin of 16 June 1904, but the quality of Dublin that survives through ever-changing forms. This guide provides the facts of Bloomsday; by using it the reader may also discover the enduring Dublin of then and of today.

Robert Nicholson

Ulysses: The Episodes

1.Telemachus 8 a.m. The Tower, Sandycove (Tour 1)

2.Nestor 9.45 a.m. The School, Dalkey Avenue (Tour 1)

3.Proteus 10.40 a.m. Sandymount Strand (Tour 2a)

4.Calypso 8 a.m. 7 Eccles Street (Tour 3)

5.Lotuseaters 9.45 a.m. Sir John Rogerson’s Quay to S. Leinster Street (Tour 4)

6.Hades 11 a.m. Sandymount to Glasnevin (Tour 2b)

7.Aeolus 12.15 p.m. The Freeman’s Journal, Prince’s Street, and the Evening Telegraph, Middle Abbey Street (Tour 6)

8.Laestrygonians 1.10 p.m. O’Connell Street to Kildare Street (Tour 6)

9.Scylla and Charybdis 2 p.m. The National Library of Ireland, Kildare Street (Tour 6)

10.Wandering Rocks 2.55 p.m. Dublin City

i. Father Conmee: Gardiner Street to Marino (Tour 3)

ii. Corny Kelleher: North Strand Road (Tour 3)

iii. The onelegged sailor: Eccles Street (Tour 3)

iv. Katey and Boody Dedalus: 7 St Peter’s Terrace (Tour 2b)

v. Blazes Boylan: Thornton’s, Grafton Street (Tour 6a)

vi. Almidano Artifoni: Front Gate, Trinity College (Tour 6)

vii. Miss Dunne: 15 D’Olier Street (Tour 2b)

viii. Ned Lambert: The Chapterhouse, St Mary’s Abbey (Tour 5b)

ix. Lenehan and M’Coy: Crampton Court to Wellington Quay (Tour 5)

x. Mr Bloom: Merchants’ Arch (Tour 5)

xi. Dilly Dedalus: Bachelor’s Walk (Tour 5)

xii. Mr Kernan: James’s Street to Watling Street (Tour 8)

xiii. Stephen Dedalus: Fleet Street and Bedford Row (Tour 5)

xiv. Simon Dedalus: Upper Ormond Quay (Tour 5)

xv. Martin Cunningham: Dublin Castle to Essex Gate (Tour 5)

xvi. Mulligan and Haines: DBC, Dame Street (Tour 5)

xvii. Cashel Boyle O’Connor Fitzmaurice Tisdall Farrell: S. Leinster Street and Merrion Square (Tour 4)

xviii. Master Dignam: Wicklow Street (Tour 6b)

xix. The viceregal cavalcade: Phoenix Park to Ballsbridge (Tour 7)

11.Sirens 3.40 p.m. Wellington Quay to the Ormond Hotel (Tour 5/5a)

12.Cyclops 5 p.m. Arbour Hill to Barney Kiernan’s, Little Britain Street (Tour 8)

13.Nausikaa 8.25 p.m. Sandymount Strand (Tour 2a)

14.Oxen of the Sun 10 p.m. Holles Street Hospital to Merrion Hall (Tour 4)

15.Circe 11.20 p.m. Talbot Street to Beaver Street (Tour 4)

16.Eumaeus 12.40 p.m. Beaver Street to Beresford Place (Tour 4)

17.Ithaca 1 a.m. Beresford Place to 7 Eccles Street (Tour 3/4)

18.Penelope 2 a.m. 7 Eccles Street (Tour 3)

Tour 1 Telemachus, Nestor

Telemachus, 8 a.m.

The Sandycove Martello Tower, known as the Joyce Tower, stands on a rocky headland one mile southeast of Dun Laoghaire, off the coast road. To get there take the train to Sandycove Station and walk down to the sea, where the Tower on Sandycove Point will be clearly visible. Cars should be parked by the harbour as the Tower is on a narrow road. Turn off Sandycove Avenue at the harbour and walk up past the distinctive white house designed as his own residence by the Irish architect Michael Scott, who also designed the present Abbey Theatre, the central bus station in Store Street and other notable public buildings. Follow the path behind the house leading to the Tower.

They halted while Haines surveyed the tower and said at last:

–Rather bleak in wintertime, I should say. Martello you call it?

–Billy Pitt had them built, Buck Mulligan said, when the French were on the sea. But ours is the omphalos.

Coincidentally enough, the order for the building of this tower, and others in the area, was dated 16 June 1804. Altogether about fifty towers of similar design were erected at strategic points on the Irish coast, of which more than half guarded the shores of County Dublin. The name ‘Martello’ comes from Mortella Point in Corsica, where the original tower was captured, and later copied, by the British. The expected Napoleonic invasion, however, never took place, and most of the towers were demilitarised in 1867. The Sandycove Tower was one of those retained, along with the nearby battery where frequent artillery practice was a source of discomfort, according to Weston St John Joyce (no relative), to nearby residents whose windows were shattered by the concussions.

1. Sandycove Point, looking eastwards from the coast road. The ladder may be seen beneath the door of the Tower, and the structure visible to the left of the Tower, behind the rooftop, was an outdoor privy.

Eason Collection

EAS

1760, courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

.

2. Sandycove Point in 1904: A map from the lease signed by Oliver Gogarty. The dotted line around the Tower and battery shows the War Department boundary line with its boundary stones. The ‘creek’ of the bathing place can be seen to the right of the battery.

Courtesy of the James Joyce Museum

.

To their relief the positions were demilitarised in 1897, and in 1904 the Tower was available for rent at the sum of £8 a year. The letting was taken by Joyce’s friend and the model for Buck Mulligan, Oliver St John Gogarty, in August 1904. Gogarty’s plan was to establish the Tower as an omphalos or new Delphi where he could invite other young writers and kindred spirits to join him in the preaching of a modern Hellenism and more convivial pursuits. James Joyce, who arrived on 9 September, was probably more interested in having a roof over his head. His friendship with Gogarty was already cooling and he left precipitately during the night of 14/15 September, never to return.

Gogarty stayed in the Tower regularly, and continued to occupy it up to 1925. Many literary friends visited him there, including George Russell (‘A.E.’) who painted a picture on the roof, Padraic Colum, Seamus O’Sullivan, Arthur Griffith and possibly also W. B. Yeats, who was reluctantly persuaded to take a swim in the Forty Foot. The Tower might well be known now as ‘Gogarty’s Tower’ had Joyce not used it as the setting for the opening of Ulysses. His implication that he himself had paid the rent effectively meant that he stole the Tower for posterity.

The James Joyce Museum, originally run by the Joyce Tower Society, was officially opened by Sylvia Beach, the publisher of Ulysses, on Bloomsday 1962. The members of the Society, a voluntary organisation, were brave but unable to carry the financial and administrative burden of running a museum, and within two years it was placed in the hands of the regional tourism organisation. In 2022 the licence was transferred to Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council and the Tower is now governed by its own management company, under whose auspices it is run by a curator with the assistance of voluntary staff and kept open throughout the year. For up-to-date information on opening hours, call the Museum at (01) 2809265 or consult its website (www.joycetower.ie).

Access to the Tower is through the modern exhibition hall, added in 1978. Pass the admission desk and turn right through the new doorway in the base of the tower. At the back of the gunpowder magazine is a narrow spiral staircase leading up to the rooftop, where Ulysses begins.

3 ‘Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him on the mild morning air.’ Around the central gunrest, which Mulligan mounts for his parody of the Mass, and the step beneath the parapet run two rails which supported a gun carriage, swivelling from the pivot in the centre.

Stephen Dedalus, ‘displeased and sleepy’, follows Mulligan from the stairs and watches as he anticipates the whistle of the departing mailboat (the jet of steam in the harbour would have been visible a couple of seconds before the sound reached the tower). The step across the doorway where Stephen leaned his arms has since been removed to make access easier. ‘Chrysostomos’, the word which occurs to him as he observes the gold fillings in Mulligan’s teeth gleaming in the sunlight, means ‘golden-mouthed’, a reference to St John Chrysostomos, who was an early father of the Church and, appositely enough, a namesake of Mulligan and his original, Gogarty, who 4 both have ‘St John’ as a middle name. While Mulligan shaves, he and Stephen talk about their companion Haines and his nightmare about a black panther. Haines’s real-life counterpart was Gogarty’s Anglo-Irish friend Samuel Chenevix Trench, and Joyce, as we shall see, had good cause to remember the nightmare. Mulligan then calls Stephen to look at ‘The snotgreen sea. The scrotumtightening sea.’

5 ‘Stephen stood up and went over to the parapet. Leaning on it he looked down on the water and on the mailboat clearing the harbourmouth of Kingstown.’ Kingstown, named to celebrate the departure of King George IV in 1821, reverted to its original name of Dun Laoghaire with the coming of Irish independence in 1922. To the east can be seen the Muglins, a small island with a beacon, and on the next point at Bullock is another Martello tower of almost identical design. To the north, on the far side of the bay, is Howth Head, where Bloom proposed to Molly. Nearby on Sandycove Point is the half-moon battery built with the Tower, beside the Forty Foot bathing place. According to Thom’s Directory, most of the houses presently on Sandycove Point were there in Joyce’s time (but the house next door is entirely modern). Stephen, however, can only look at ‘the ring of bay and skyline’ and compare it in his mind to the bowl into which his dying mother 6 had vomited. Mulligan’s teasing about his appearance only makes his mood worse as they walk around the Tower arm in arm.

7 ‘They halted, looking towards the blunt cape of Bray Head that lay on the water like the snout of a sleeping whale.’ Bray Head is not, in fact, visible from the Tower – it is to the south beyond Killiney, whose hill with an obelisk is on the skyline – and scholars continue to agonise over whether this is a genuine slip or a deliberate error. Some diehards have drawn comfort from the possibility that the word ‘towards’ does not necessarily mean that they were looking at the Head.

8 Following his argument with Stephen, Mulligan goes downstairs, leaving Stephen to brood alone while the sun, by now somewhere over the Muglins, 9 disappears behind a cloud. His reverie about his mother reaches an anguished climax just as Mulligan returns to bid him to breakfast.

10 Stephen descends halfway down the stairs to enter ‘the gloomy doomed livingroom of the tower’. To the left is the fireplace between the two window shafts (called ‘barbacans’ by Joyce); to the right is the heavy door opened by Haines to let in ‘welcome light and bright air’ from the sunny side of the building. It is unused now, and the huge key is on display downstairs. None of the original furniture (mainly supplied by Gogarty from his family home in Parnell Square) remains, but the room has now been refurnished from the evidence of contemporary documents to give an impression of the scene as it was at the time, with a shelf around the walls, a small cooking range and beds in the corners. The floor was in fact wooden rather than ‘flagged’, and Haines’s hammock was probably Joyce’s invention as there was nothing to sling it from.

It was here, on the night of 14 September 1904, that Joyce, Gogarty and Trench were sleeping when Trench had a nightmare about a black panther which he dreamed was crouching in the fireplace. Half-waking, he reached for a gun and loosed off a couple of shots to scare the beast away before going back to sleep. Gogarty promptly confiscated the gun. ‘Leave the menagerie to me,’ he said when Trench’s nightmare returned, and fired the remaining bullets at the saucepans over Joyce’s head. Joyce leapt out of bed, flung on his clothes and left the Tower immediately. He walked all the way into Dublin and appeared at the National Library at opening time. He never returned to the Tower, and the following evening he and Nora Barnacle made their decision to leave Ireland.

The big door was the only way in and out of the Tower, and was approached by a step ladder attached 11 to the outside wall. As the three men begin their breakfast, Haines sees the old woman coming with the milk, and they have time to exchange a page of dialogue before she reaches the top of the ladder.

The doorway was darkened by an entering form.

–The milk, sir!

12 Haines, anxious to try out his Irish on a native, speaks to her in Gaelic, which Joyce does not attempt to reproduce. Haines’s original, Trench, was a keen student of the Gaelic Revival and took every opportunity to air his Connemara Gaelic, which was unfortunately marred by a strong Oxford accent.

13 The milkwoman is paid her bill (somewhat reluctantly) by Mulligan and leaves. Mulligan, obviously hopeful of getting money or drink from his friends, urges Stephen to ‘Hurry out to your school kip and 14 bring us back some money’ and encourages Haines to add Stephen’s Hamlet theory to his collection of Irish studies. Stephen embarrasses him by asking tactlessly, ‘Would I make any money by it?’

15 Mulligan gets dressed and the three leave the Tower to walk to the Forty Foot. Before following their path, it is worth lingering in the Tower to view the collection, which includes several of Joyce’s possessions and manuscript items, first editions of Ulysses and other works, and all sorts of photographs, paintings and miscellaneous Joyceana. Joyce’s guitar, waistcoat and travelling trunk may be seen, as well as one of the two death masks made by the sculptor Paul Speck in Zurich. Among the Ulysses trivia are the key pocketed by Stephen, a Plumtree’s Potted Meat pot and an original photograph of Throwaway, the outsider which won the Ascot Gold Cup and indirectly led to Bloom’s hasty departure from Barney Kiernan’s. Books are available for purchase at the entrance desk..

Leaving the museum, turn left down the path along the top of the cliff, where Mulligan chants his 16 ‘ballad of Joking Jesus’ on the way to the bathing place.

17 Stephen follows with Haines, foreseeing correctly that Mulligan will obtain the key from him and prevent him returning to the Tower. He explains to Haines how he is the servant of two masters – Britain and the Roman Catholic Church – and a third ‘who wants me for odd jobs’; this last, though unspecified, is probably Irish nationalism. In his mind he has a vision of the Church and its banishment of all those who dared contest its dogmas.

18 They followed the winding path down to the creek. Buck Mulligan stood on a stone, in shirtsleeves, his unclipped tie rippling over his shoulder. A young man clinging to a spur of rock near him, moved slowly frogwise his green legs in the deep jelly of the water.

The sign at the entrance to the bathing place once read, ambiguously, ‘Forty Foot Gentlemen Only’. The latest wisdom on the mysterious origins of the name suggests that an offshore fishing ground gave the title to what became known as the Forty Foot Hole. The bathing place itself is only half that depth and has a long and colourful history. Probably established as a men’s bathing place by the soldiers of the battery garrison in the early 1800s, it was maintained by regular bathers who in 1880 formed the Sandycove Bathers’ Association. The granite screening wall protecting bathers from the east wind and the public gaze was built in the 1890s, while the concrete shelters, erected in 1969, replaced a Victorian structure on the same spot. Nude bathing, once very much the custom at the Forty Foot, has declined since women starting bathing there in the 1970s, although the Sandycove Bathers’ Association remained by constitution an all-male body up to 2014. In 2015 responsibility for the Forty Foot was taken over by the County Council, and the Association retains only a social rôle.

19 Stephen has awaited the moment when Mulligan will demand the key, and has even gone out of his way to the Forty Foot to give Mulligan the opportunity. Finally he has to prompt him by announcing his departure, and the ‘usurper’ does what is expected of him.

‘—And twopence, he said, for a pint. Throw it there.’ Mulligan and Haines arrange to meet him again at The Ship pub, where presumably he will be expected to buy them drink. He leaves them and walks back up the path on his way to Dalkey.

The most direct route, and the one which Stephen probably took, goes by way of Sandycove Avenue East and left along Breffni Road and Ulverton Road, passing Bullock Castle on the left. The castle, built in the thirteenth century, dates from the time when Bullock Harbour was the principal port of entry to Dublin for traders from abroad. Several castles in this area guarded the port and the lands of rich monasteries round about. The castle is now attached to Our Lady’s Manor, a home for elderly people.

At the far end of Ulverton Road is the village of Dalkey, which in Joyce’s day was the last stop on the tramline from Dublin. Dalkey has been celebrated by two later Irish writers, Flann O’Brien and Hugh Leonard. Flann O’Brien’s comic novel The Dalkey Archive (1964) involves a demented scientist named De Selby who plans to destroy the world with a patent substance known as DMP; also featured is James Joyce, who is discovered alive and well and claiming that Ulysses was a smutty book compiled under his name by a ghostwriter. Hugh Leonard’s plays Da (1973) and A Life (1980) and his autobiography Home Before Night (1979) lovingly recreate the Dalkey of his childhood in the 1930s. A Heritage Centre in the castle in the main street tells the story of Dalkey – including its Joycean connection and other literary links – through exhibits, images and information panels. A visit to the battlements provides a view of the local topography. The Centre is open every day except Tuesday.

Stephen’s route continues up Dalkey Avenue as far as the corner with Old Quarry on the right.

Nestor, 9.45 a.m.

20 —You, Cochrane, what city sent for him?

—Tarentum, sir.

On the corner of Dalkey Avenue and Old Quarry, just a mile from the Tower, is a large, very rambling house named ‘Summerfield’. It was once the home of the poet Denis Florence McCarthy (1817–82), whose Poetical Works