7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

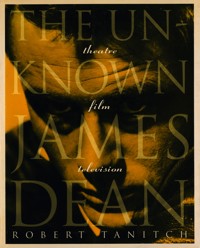

This biography, lavishly illustrated, traces Dean's development as an actor through his film work and numerous lesser-known roles in the theatre and television.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 225

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

THE UNKNOWN JAMES DEAN

Forty years after his death, the memory of James Dean’s mercurial talents remains undiminished. This lavish pictorial study highlights not only Dean’s film career but also his less familiar work in theatre and television.

THE UNKNOWN JAMES DEAN traces Dean’s development as an actor through his numerous roles in theatre and television when he worked with the leading authors, directors and actors of the day (including Ronald Reagan!).

THE UNKNOWN JAMES DEAN is handsomely illustrated throughout with both classic and less familiar stills and portraits, and also looks at the documentaries, films and plays which have been inspired by Dean’s life and work.

ROBERT TANITCH, playwright, author, critic, has published 12 highly acclaimed theatre and filmographies. These include books on the careers of Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Alec Guinness, Dirk Bogarde, John Mills, Sean Connery and Marlon Brando.

THE UNKNOWN JAMES DEAN

THE UNKNOWN JAMES DEAN

ROBERT TANITCH

CONTENTS

Introduction

Theatre

Television

Film

Documentary

Related Works

Awards

Chronology

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

JAMES DEAN, an actor of outstanding promise, never lived to see his fame, his career tragically cut short almost before it had begun. This book is a pictorial record and chronology of his work in theatre, television and film.

James Dean’s fame as an actor rests on three roles: Cal Trask, the bad twin, in John Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1955), directed by Elia Kazan; Jim Stark, the definitive 1950s teenager, in Rebel Without a Cause (1956), directed by Nicholas Ray; and Jett Rink, the cowhand turned megalomaniac tycoon, in Edna Eerber’s Giant (1957), directed by George Stevens. He was nominated for an Oscar for two out of these three films, but strangely, not for his best performance.

For those who know only of Dean’s acting career through these films, it may come as a surprise to learn that between 1951 and 1954 he acted in two major stage roles in New York and in over 30 plays on television, appearing in works by John Drinkwater, William Inge, George Roy Hill, Rod Serling and adaptations of Sherwood Anderson and Henri Bernstein. It is a reminder (if a reminder is needed) that actors do not suddenly appear out of nowhere.

His roles on television tended to be crazy mixed-up kids, teenage delinquents on the run, vagrants, convicts, safe-crackers, counterfeiters and killers, though from time to time he was also cast as a farm boy, a bellhop, a lab assistant, a stevedore and, perhaps more unexpectedly, as a French aristocrat, an apostle and even an angel.

His roles in the theatre included the simpleton in Richard J. Nash’s See The Jaguar (1952), the homosexual Arab street boy in Ruth and Augustus Goetz’s adaptation of André Gide’s novel, The Immoralist (1954), and Herakles in a Sunday night reading of Sophocles’s The Women of Trachis (1954) in a racy translation by Ezra Pound.

James Dean in The Immoralist

Right at the very beginning of his career he landed bit parts in three minor Hollywood movies, playing a GI in Korea in Samuel Fuller’s Fixed Bayonets! (1951), a boxer’s second in the Dean Martin–Jerry Lewis comedy, Sailor Beware! (1952), and a young man ordering an ice-cream sundae in Has Anybody Seen My Gal (1952).

James Byron Dean, son of Winton and Mildred Dean, was born during the American Depression on 8 February 1931 in Marion, Indiana. The family moved to Los Angeles in 1936 and shortly afterwards his mother died of cervical cancer when she was 29 and he was only 9. Her death left him insecure and vulnerable for the rest of his life. ‘What did she expect me to do?’ he would ask later. ‘Do it all on my own?’

His father, a dental technician, sent him back to Fairmount, Indiana, alone (accompanied by his mother’s coffin) to be raised by his aunt and uncle on their 180-acre farm. He saw little of his father thereafter. His aunt was a member of the Women’s Christian Union and he learned religious tracts on the evil of drink, which he read to the congregation in the church, his first tentative steps in drama.

At Fairmount High School he was an average student, who was good at athletics and played in the basketball team. He took part in a number of school productions, mainly melodramas, and entered a speech competition, coming first at State level and sixth at the National level. His text was ‘The Madman’s Manuscript’ from Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers.

James Dean in East of Eden

In 1949 he enrolled in the pre-Law programme at Santa Monica City College, choosing as his subsidiary subject the history of theatre arts. He joined the Jazz Club and Jazz Appreciation Society. He painted the scenery for The Romance of Scarlet Gulch at the Miller Playhouse Theater Guild and appeared in the Santa Monica Theater Guild production of She Was Only A Farmer’s Daughter.

In 1950 he gave up Law and enrolled at the University of California to study Theatre and played Malcolm in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, his Indiana twang causing much amusement among the students.

In January 1951 he dropped out of university and went to New York and successfully auditioned for The Actors Studio (known to its detractors as ‘the slouch and mumble school’) becoming one of their youngest members. His idols were Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift and such was his obsession with both actors that he would sometimes sign his letters James-Brando-Clift-Dean. He took dancing lessons with Katherine Dunham.

He made his Broadway debut in 1952 in Richard J. Nash’s See The Jaguar as a simple-minded and bewildered lad who had been locked up in an ice-house all his life. The play was dismissed as sententious and baffling. ‘If you want to see See The Jaguar,’ advised John McClain in The New York Journal American, ‘you had better hurry.’ Theatregoers who did not hurry missed it. The production ran five nights. Dean’s notices, however, were excellent (Lee Mortimer, critic of The New York Daily Mirror, thought he stole the show) and they led to television engagements.

The early 1950s was the Golden Age of Television in America and drama was one of its staple diets. Dean was one of many young actors who took advantage of the open casting calls. The teledramas were cheaply made, underrehearsed, poorly designed, flatly lit and crudely staged, but they were an excellent training ground. In the same way that a British actor in the 1950s got his experience in weekly repertory so the New York actor got his experience on television.

His first role was in a religious drama, Hill Number One, for Family Theatre (‘The family that prays together stays together’) in which he was cast as John the Apostle in a retelling of the story of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection.

Between 1952 and 1955 it must have seemed as if he was never off the box, acting opposite such actors as E. G. Marshall (Sleeping Dogs), Cloris Leachman (The Forgotten Children), Rod Steiger (The Evil Within), Gene Lockhart (The Bells of Cockaigne), Dorothy Gish and Ed Begley (Harvest), Mildred Dunnock (Padlock), Eddie Albert (I’m a Fool), Mary Astor and Paul Lukas (The Thief) and Ronald Reagan (The Dark, Dark Hour).

He also worked for such prestigious television series as Omnibus in William Inge’s Glory in the Flower, which starred Jessica Tandy and Hume Croyn, and Schlitz Playhouse in The Unlighted Road in which he was the star.

The shows were live but many of the video tape backups (in case of an emergency on the day of transmission) have been found and these are preserved and can be seen at The Museum of Television and Radio in New York on consoles.

Dean quickly developed a reputation among directors and actors of being difficult to work with. ‘I don’t see how people stay in the same room with me,’ he once said. ‘I know I wouldn’t tolerate myself.’ The complaints were legion: he was ill-mannered, he arrived late, he didn’t learn his lines, he didn’t stick to the script. He may have been good at improvising on the spot and using the props around him, but he was not so good at finding his marker on the floor and often moved out of the frame. His spontaneity and unpredictably worried and annoyed actors not brought up in the Method school of acting.

In 1954 he was cast as Bachir, the homosexual Arab houseboy in Ruth and Angus Goetz’s adaptation of André Gide’s The Immoralist, starring Geraldine Page and Louis Jourdan. Though the play was perhaps the most serious and outspoken treatment of homosexuality that Broadway had yet seen, the subject was treated so clinically that there was no drama. Dean, however, got excellent reviews, his performance admired for its realistic venality and insidious charm. He left the cast almost immediately after the first night having landed the leading role in Elia Kazan’s film version of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden.

His film debut was an overnight sensation: ‘unquestionably the biggest news Hollywood has made in 1955... the screen’s most sensational find of the year... the most dynamic star discovery of the year... outstanding talent... the best youngster to hit the screen in years... destined for a blazing career’.

Influential film columnist Louella Parsons guaranteed her readers that ‘the twenty-three-year-old actor from Broadway will be the rave of the season.’ Her rival Hedda Hopper was not to be outdone: ‘I do not remember’, she wrote, ‘ever having seen a young man with such power, so many facets of expression, so much sheer invention as this actor.’

Cal Trask was a wonderful role for an actor’s screen debut. There was hardly a scene in which he did not appear and he was very photogenic. For those who admired his performance, his ability was strikingly in evidence. He was likened to a captive panther and a young lion and said to have the grace of a tired cat. His good looks, his sensitivity and his dynamism were much commented on. Those who didn’t like his performance found him stylized, hard to understand and too much on one note. They saw merely a carboning of Marlon Brando’s acting style, personality and mannerisms without Brando’s talent and power.

There was hardly a critic who didn’t compare Dean with Brando. True, they had been to the same school, the same Method school of acting, The Actors Studio, and Dean had acquired the Method’s characteristic vocal and physical mannerisms. But he was nothing like Brando. Brando was 30 and looked it. Dean was 24 and looked like a teenager.

By the time East of Eden was released, Brando had appeared in The Men, A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata, Julius Caesar, The Wild One, On the Waterfront, Desirée and Guys and Dolls. It is difficult to imagine Dean playing Stanley Kowalski, Zapata, Mark Antony, Terry Malone, Napoleon Bonaparte and Sky Masterton. He would have been the right age for The Wild One (righter than Brando at any rate) yet hardly convincing as leader of The Black Rebels’ Motor Cycle Club.

Dean’s admiration for Brando was wellknown but he was understandably irritated by the comparison. ‘I have my own personal rebellion,’ he was quoted as saying in Newsweek. ‘I don’t have to rely on Brando’s.’

Brando was equally irritated: ‘I have a great respect for his talent. However, in East of Eden, Mr Dean appears to be wearing my last year’s wardrobe and using my last year’s talent.’ Despite the specific reference to East of Eden, I suspect his remark was based more on Dean’s off-screen behaviour rather than his on-screen performance. It would have been fascinating to see them acting together in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, cast as the Tyrone brothers, Dean as consumptive Edmund Tyrone opposite Brando’s drunken James.

James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause

James Dean in Giant

Originally Kazan had wanted Brando and Montgomery Clift to play the bad and good twins in East of Eden but, by the time he had managed to get the production off the ground, they were too old.

Since there were no box office names in East of Eden, the film opened to middling business until Dean’s death gave the box office the boost it needed. Cal Trask was not, of course, the first of his tortured, inarticulate adolescents – he had already played endless variations on the role on television – but it was the first time the mumbling, the stricken face, the delicate bruised emotions, the upturned eyes, the wrinkled brows, the Kabuki-like knit eyebrows and the hunched shoulders had been seen on the big screen. His vulnerability created enormous empathy. He was not Steinbeck’s Cal (though Steinbeck said he was) but rather Dean’s Cal. It was an astonishing performance for his first major film.

He was nominated for an Oscar. So were James Cagney in Love Me or Leave Me, Frank Sinatra in The Man with the Golden Arm and Spencer Tracy in Bad Day at Black Rock. They all lost to Ernest Borgnine in Marty. Elia Kazan was also nominated for an Oscar and he lost out, too, to Delbert Mann, the director of Marty.

East of Eden was the only time Dean got to witness his success. Rebel Without a Cause (billed as ‘Warner Bros Challenging Drama of Today’s Teenage Violence’) was premiered four weeks after his death. The film was not only a seminal work on juvenile delinquency but also a damning indictment of parental shortcomings, and as such, it had an obvious appeal to adolescent audiences. Dean became an instant star, an instant symbol of and for disillusioned youth, a prototype rebel, epitomizing every 1950s teenager’s frustration and isolation. His affinity with the role was patent and it was the role which would do most to create and perpetuate his image and posthumous myth and cult.

His close relationship with the director, Nicholas Ray, gave him tremendous creative freedom, allowing him to develop his character and even shape the movie itself. No one had previously portrayed the angst, insecurity and bewilderment of youth quite so well. Rebel Without a Cause was, perhaps, the first film in which an actor had portrayed a teenager with whom other teenagers the world over could identify. ‘Take both your parents to see it’, advised one newspaper’s headline. The film would be much imitated.

Once again his reviews were excellent: ‘a remarkable talent... a player of unusual sensibility and charm... exceptional power and sensitivity... unusually gifted... brilliant... his intensely original performance has the marks of greatness... (and in one silly headline) Not Even Brando Could Equal This’.

His next role was Jett Rink in Edna Ferber’s Giant, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson, and directed by veteran director George Stevens who (to Dean’s undisguised annoyance) did not give him the freedom Kazan and Ray had. Jett Rink was a relatively small part, a supporting role, though important enough for many of Hollywood’s leading actors to want to play him. At the premiere, a year after his death, Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson found themselves playing a supporting role to Dean whose every appearance on the screen was greeted with an ovation.

The critics were divided about the film, their evaluations ranging from ‘a large and satisfying entertainment’ to ‘as indigestible as a Texan breakfast of steak, fried eggs and beans’. The critics were also divided about Dean. There were those who thought he was ‘great... magnificent... the most brilliant of all the young players Hollywood has discovered since the war... a tour de force’. There were many who did not find him great at all. ‘Since Dean is dead I shall say nothing about his attempt to portray the mature Jett Rink,’ wrote Courtland Phipps in Films in Review, ‘except to say it is embarrassing to see.’ Georges Sadoul went further. Writing in Les Lettres françaises, he said Dean had ‘descended to third-rate acting’.

The real problem was that he had to age 30 years. Some people were surprised how convincing he was as a middle-aged, power-crazy tycoon; the majority did not find him convincing at all. He was inevitably much more persuasive in the first part of the movie as a young and inarticulate ranchhand. Nevertheless, he was nominated for an Oscar, no doubt because he was dead and no doubt out of respect for the box-office as well. Rock Hudson was also nominated. So were Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life, Laurence Olivier in Richard III and Yul Brynner in The King and I. Brynner got the award.

Apart from acting, Dean’s other great obsession was cars and racing. On 30 September 1955, less than two weeks after completing Giant, he was driving to Salinas to participate in a race when he was killed in a crash with another car. He was 24 years old.

‘Dean’s career is not over,’ affirmed the Reverend Xen Harvey, officiating at the funeral and getting carried away by the occasion. ‘It’s only the beginning and remember God is directing the production.’

There had been nothing since the death of Rudolf Valentino in 1929 to equal the mass hysteria which followed. Fans worldwide refused to believe he was dead. There were rumours he was still alive and disfigured in a sanatorium. His homes were ransacked. His Porsche was put on exhibition and dismantled by people wanting souvenirs. Dean became much more famous when he was dead than he had been when he was alive.

For three years after his death he was receiving more letters than any living star. He was widely copied, his image appearing everywhere, on posters, T-shirts, mugs, clocks, even tattooed on people’s backs. In the decades which followed he would continue to be seen on hoardings and in commercials helping to sell jeans and banks. Forty years on, he is still in vogue, remembered more vividly than many better actors with far longer careers.

Had he lived he was set to appear on television as the Welsh miner in Emlyn Williams’s The Corn is Green and in two boxing films, an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s The Battler and Somebody Up There Likes Me, the latter the story of Rocky Graziano, played eventually by Paul Newman, who had been a strong contender for East of Eden. Nicholas Ray was convinced that, had he lived, he would have discarded acting entirely in favour of directing.

Because Dean died at 24 he remains forever young, immortalized as the ultimate teenage screen hero and rebel. He never had time to destroy his image. He was dead before his hold on the public had weakened. His last film was Giant, but his screen epitaph will always be Rebel Without a Cause. His best film, however, remains East of Eden, which offered him his greatest role and his greatest performance.

The pages which follow are a record of James Dean’s work and mercurial talent, his magnetism and charisma, and his enduring and universal appeal across the sexes and age groups.

School Days

James Dean was at Fairmount High School from September 1943 to May 1949 during which time he appeared in a number of school productions. His drama teacher was Adeline Nall, a major influence during his school days.

To Them That Sleep in Darkness

Role

Blind boy

Date

1945

The blind boy regained his sight. The play was performed at the Back Creek Friends Church where his family worshipped.

The Monkey’s Paw

Writers

W. W. Jacobs and Lewis N. Parker

Role

Herbert White

Date

1946

The monkey’s paw offered its owner three wishes. It was Herbert White who suggested his father should wish for £200 to clear the family debts. He then went off to the factory where he worked and got caught up in the machinery and was mangled to death. The firm offered his parents £200 by way of compensation. Mrs White begged her husband to wish their son alive again. The moment he did, there was a knock at the door and it grew louder and louder and more and more insistent. As she struggled with the door’s chain and bolt, Mr White wished his son dead. The knocking stopped instantly. First published in 1902, the story is regarded as one of the best ‘three wishes’ stories ever written. Dramatized in 1910. it quickly became popular with amateurs with a penchant for the macabre.

Mooncalf Mugford

Writers

Brainerd Duffield and Helen and Nolan Leary

Role

John Mugford

Date

1947

Mugford was a mad old man who had visions. Thirty-six years later in Hollywood: The Rebels, a documentary about Dean, Adeline Nall would recall how, in his enthusiasm for acting, Dean had practically throttled the poor schoolgirl who was playing his wife.

Our Hearts Were Young and Gay

Writers

Cornelia Otis Skinner and Emily Kimbrough

Adaptor

Jean Kerr

Role

Otis Skinner

Date

October 1947

The comedy was set in Paris of the 1920s and described the adventures of two unchaperoned 19-year-old girls who were courted by two young Harvard men. Dean played Cornelia Otis Skinner’s father, a famous American actor (1851–1942), probably best remembered for the beggar Hajj in Kismet.

Goon with the Wind

Roles

Villain and Frankenstein’s monster

Date

29 October 1948

Goon with the Wind was an entertainment specially produced for Hallowe’en.

You Can’t Take It With You

Writers

Moss Hart and George S. Kaufman

Role

Boris Kalenkhov

Date

1949

The Pulitzer Prize-winning You Can’t Take it with You, a gentle satire on materialism, preached a folksy message that money wasn’t everything. ‘Life’, said Hart and Kaufman, ‘is kind of beautiful if you let it come to you.’ The play, first produced in 1936 (and later filmed by Frank Capra with James Stewart) was the perfect antidote for the Depression years. It ran for 837 performances on Broadway. A cast of loveable innocents, eccentrics and dreamers has made it popular with professionals and amateurs ever since.

James Dean in an unidentified school production

James Dean in Macbeth

One of the running gags was at the expense of the Russian aristocracy, who having fled the Revolution, were slumming in New York and taking any menial job they could get. Boris Kalenkhov (Dean’s role) was a booming, hairy, exuberant, pirouetting, former ballet master who believed ‘art is only achieved through perspiration.’ He had only one pupil and she had no talent. ‘Confidentially,’ said Boris, ‘she stinks.’

The Madman’s Manuscript

Adapted from Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers

Role

Madman

Venues

Peru, Indiana; Longmont, Colorado

Dates

April 1949

The manuscript was the purported memoirs of a raving lunatic, who had long believed that hereditary madness existed in his family. He attempted to murder his wife and though he failed, the attempt itself drove her insane and to an early death. Shortly afterwards he successfully strangled her brother.

Dean acted this masterly bit of Grand Guignol (written by Dickens when he was 25 years old) as his entry for the dramatic declamation in the National Forensic League competition. He won first place at state level and sixth place at national level. He might have done even better in the Final had he kept within the time limit laid down by the Board. But, despite having been warned, he refused to cut anything, overran, and paid the penalty. He then had the gall to blame Adeline Nall for his failure.

College and University Days

James Dean was at Santa Monica City College from September 1949 to May 1950 and at the University of California, Los Angeles, from September 1950 to February 1951.

His drama teacher at College was Gene Nielsen Owen. They worked on Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart, the latter no doubt due to his success with Dickens’s Madman.

At University he studied the Method with a small group of students under the tuition of actor James Whitmore, a key figure in his development as an actor, and whose help he would always acknowledge. It was Whitmore who recommended he should go to New York.

During this period he was involved in the following productions:

The Romance of Scarlet Gulch

A melodrama with music

Role

Charlie Smooch

Theatre

The Miller Playhouse, Theatre Guild, Los Angeles

Dates

August 1949

A Summer Stock production. The action was set during the Californian Gold Rush. Charlie Smooch was a drunk. Dean (billed in the programme as Byron James) also painted the scenery.

She Was Only A Farmer’s Daughter

A melodrama by Millard Crosby

Role

Father

Theatre

Santa Monica City College

Dates

May 1950

Iz Zat So?

A revue

Role

Various

Theatre

Santa Monica City College

Dates

May 1950

Macbeth

A play by William Shakespeare

Role

Malcolm

Director

Walden Boyle

Theatre

Royce Hall, UCLA

Opening

29 November 1950

Malcolm, eldest son of the murdered King Duncan, led a victorious army (famously camouflaged as Birnam Wood) against Macbeth. Harve Bennett, a student at UCLA, writing in the university’s Theatre Arts newsletter, Spotlight, said that ‘Dean had failed to show any growth and would have made a hollow king.’

William Bast, also a student, and later his friend and biographer, thought it was the worst performance he had ever seen and that Dean had no chance of an acting career whatsoever.

The Actors Studio

“After months of auditioning I am very proud to announce that I am a member of The Actors Studio. The greatest school of theatre. It houses great people like Marlon Brando, Julie Harris, Arthur Kennedy, Elia Kazan, Mildred Dunnock, Kevin McCarthy, Monty Clift, June Havoc and on and on and on. Very few get into it, and it’s absolutely free. It’s the best thing that can happen to an actor. I am one of the youngest to belong. If I can keep up and nothing interferes with my progress, one of these days I might be able to contribute something to the world.

James Dean in a letter to his uncle and aunt

The Actors Studio was a New York-based workshop for professional actors founded by Elia Kazan, Cheryl Crawford and Robert Lewis. Lee Strasberg was the artistic director from 1951 to 1982.

The Studio was not a school and it was very difficult to get into; but once an actor was accepted as a member, he was a member for life. Here actors studied the Method, an introspective approach to acting based on Stanislavsky. The aim was to create a character from within through improvisation. The school’s mumblings, hesitations and naturalistic business were made famous by Marlon Brando in Elia Kazan’s stage and film productions of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront.

James Dean became a member in 1952 and over the next two years appeared in a number of productions and staged readings on Broadway, Off-Broadway and in in-house performances at The Studio.

Matador

Adapted from a novel by Barnaby Conrod

Role

Matador

Venue

The Actors Studio

Date

1952