16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

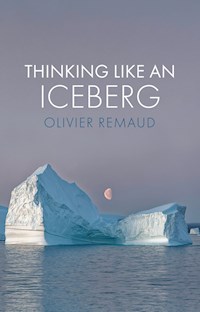

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

When we imagine the polar regions, we see a largely lifeless world covered in snow and ice where icebergs drift listlessly through frozen waters, like solitary wanderers of the oceans floating aimlessly in total silence. But nothing could be further from the truth. This book takes us into the fascinating world of icebergs and glaciers to discover what they are really like. Through a series of historical vignettes recalling some of the most tragic and most exhilarating encounters between human beings and these gigantic pieces of matter, and through vivid descriptions of their cycles of birth and death, Olivier Remaud shows that these entities are teeming with many forms of life and that there is a deep continuity between iceberg life and human life, a complex web of reciprocal interconnections that can lead from the deadliest to the most vital. And precisely because there is this continuity, icebergs and glaciers tell us something important about life itself - namely, that it thrives in the most unexpected of places, even where there seems to be no life at all. At a time when we are increasingly aware that the melting of ice sheets, glaciers and sea ice is one of the many disastrous consequences of global warming, this beautiful meditation is a poignant reminder of the interconnectedness of all life and the fragility of the Earth's ecosystems.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

The Issue

Prologue: They are Coming!

1 Through the Looking Glass

A game of hide and seek

Framing icebergs

The reign of the sublime

Lonely spectres

A story about skulls

Mirror, my beautiful mirror

Notes

2 The Eye of the Glacier

So other, so close

Way up above

A vocabulary crisis

The wanderings of a happy man

Are icebergs whale calves?

The spirit of laws

Do not choose the wrong world

Notes

3 Unexpected Lives

Disordered perception

Living ice

Iceberg portraits

All power to the verbs!

Incorporation/orientation

Noise and breath

The ear before anything else

Notes

4 Social Snow

The original iceberg

Practical words

The sea ice as an institution

Sensitive colossi

‘We are sleepwalking’

Respecting distance

Notes

5 A Less Lonely World

An endangered species

Empty or full?

Suddenly, nothing at all

Proof through emotion

The resistance of rocks

What separates and what unites

Notes

6 Thinking Like an Iceberg

Notes

Epilogue: Return to the Ocean

End User License Agreement

List of Illustrations

Chapter 1

Figure 1

Frederic Edwin Church, The Icebergs (1861–3), Dallas Museum of Art

Chapter 2

Figure 2

Diagrams extracted from Douglas I. Benn and Jan A. Åström, …

Chapter 3

Figure 3

Camille Seaman, Stranded Iceberg, Cape Bird, Antarctica, 2006.

Figure 4

Last Iceberg, Series I, II, III

Figure 5

Sound recording of WhiteWanderer Riverside

Chapter 5

Figure 6

Bréf til framtiðarinnar / A letter to the future.

Figure 7

Rise: From One Island to Another, a film by Dan Lin, Nick Stone, …

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Begin Reading

Epilogue

End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

183

Thinking Like an Iceberg

Olivier Remaud

Translated by Stephen Muecke

polity

Originally published in French as Penser comme un iceberg © Actes Sud, 2020

This English edition © Polity Press, 2022

Excerpt from Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez reprinted by permission of SLL/Sterling Lord Literistic, Inc. Copyright 1986 by Barry Lopez.

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-5148-4

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021949632

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website:politybooks.com

The frozen ocean itself still turns in its winter sleep like a dragon.

— Barry Lopez, Arctic Dreams

Acknowledgements

I would first like to thank Stéphane Durand at my French publisher, Actes Sud, for welcoming this book into his ‘Mondes sauvages’ series and for following every step of the process with attention and friendship.

I also thank Stephen Muecke for his translation into English and Elise Heslinga at Polity.

For their help in various ways (bibliography, translation, proofreading, illustrations, conversations), my gratitude goes to Glenn Albrecht, Þorvarður Árnason, Caroline Audibert, Petra Bachmaier, Chris Bowler, Aïté Bresson, Garry Clarke, Stephen Collins, Julie Cruikshank, Philippe Descola, Élisabeth Dutartre-Michaut, Katti Frederiksen, Sean Gallero, Samir Gandesha, Shari Fox Gearheard, Hrafnhildur Hannesdóttir, Lene Kielsen Holm, Cymene Howe, Nona Hurkmans, Guðrún Kristinsdóttir-Urfalino, José Manuel Lamarque, David Long, Robert Macfarlane, Andri Snær Magnason, Rémy Marion, Christian de Marliave, Markus Messling, Éric Rignot, Camille Seaman, Charles Stépanoff, Agnès Terrier, Torfi Tulinius, Philippe Urfalino, Daniel Weidner and Stefan Willer.

Finally, I am indebted to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the Leibniz Zentrum für Literatur und Kulturforschung in Berlin and the Institute for the Humanities at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver for allowing me to present parts of the manuscript as I was preparing it.

The Issue

Icebergs have been considered secondary characters for a long time now. They made the headlines when ships sank after hitting them. Then they disappeared into the fog and no one paid them any more attention.

In the pages that follow, they take centre stage. Their very substance breathes. They pitch and roll over themselves like whales. They house tiny life forms and take part in human affairs. Today, they are melting along with the glaciers and the sea ice.

Icebergs are central to both the little stories and the big issues.

This book invites you to discover worlds rich in secret affinities and inevitable paradoxes.

There are so many ways to see wildlife with new eyes.

PrologueThey are Coming!

The morning was dark. Fog was suspended over our heads. Pancakes of ice floated near the ice edge. The sea seemed sluggish.

Then a discreet sun lit up the horizon.

Three points appeared in the distance. A thin silhouette emerged from the fog. I could not immediately identify the shape, but it was becoming more and more curved. No whale has these spurs on its back; my nomadic brothers are larger.

The clouds began to glow.

A ship was approaching us.

It was making slow progress. Like a lost penguin, it took small steps sideways. When it anchored in our vicinity, I saw them stirring. They were huddled together on the forecastle, jumping up and down in a strange dance. They were pointing at me. Their faces were long, their beards shaggy, and they smelt strong. They looked like ghosts. I could only make out the males. Some smiled, others opened their mouths but no words came out. With their hands on the main mast, some were kneeling and bowing their heads. They crossed themselves as they stood up.

A man emerged from a cabin at the back of the ship. He climbed the stairs leading to the deck. A group followed him. Drumbeats echoed in the silence of the ocean. When the music stopped, he was announced by one of his companions.

Captain James Cook looked at the assembled crew and then addressed his sailors. His clear voice carried a long way. He told them that they had sailed far and wide, so far across the ocean at this latitude that they could no longer expect to see any more dry land, except near the pole, a place inaccessible by sea. They had reached their goal and would not advance an inch further south. They would turn back to the north. No regrets or sadness. He prided himself on having fulfilled his mission of completing his quest for an Antarctic continent. He seemed relieved.

As soon as the captain’s speech was over, a midshipman rushed to the bow. He climbed over the halyards and managed to pull himself up onto the bowsprit. There, balancing himself, he twirled his hat and shouted, ‘Ne plus ultra!’ Cook called the young Vancouver back to order, urging him not to take pride in being the first to reach the end of the world. Screaming thus in Latin that they would go ‘no further!’ made him unsteady over the dark waters. He could fall into oblivion with the slightest gust of wind. The crew burst out laughing. With a smile on his face, the reckless hopeful returned to the bridge like a good boy. Then they turned their backs on me and went back to their tasks, some disappearing into the bowels of the ship while others climbed up to the sails.

Those three words echoed in the sky. I remember it with pride.

Call me ‘The Impassable’.

I am the one who stopped Cook on his second voyage around the world, the happy surprise that cut short his labours at 71° 10’ latitude south and 106° 54’ longitude west.

I am one of the icebergs on which the Resolution, a three-masted ship of four hundred and sixty-two tons, would have crashed if the fog had not cleared. On that day, 30 January 1774, they saw me in all my imposing, menacing volume.

My comrades from Greenland are slender. I am flat and massive. I blocked the way without giving them the chance of going around me. In any case, there is only ice behind me, an infinity in which they would have become lost. I saved them from a fatal destiny.

Thanks to me, an entire era thought that no one before the captain had gone so far south, that he was the sole person, the only one, the incredible one to have achieved this feat. What can I say about the snow petrels that have been landing on my ridges for centuries? I am familiar with these small white birds with black beaks and legs. They are attracted by the tiny algae that cling to my submerged sides.

Cook and his sailors kept their distance. Except for the times when they took picks and boarded fragments of iceberg from longboats. They climbed over them, dug them up and extracted blocks of ice which they left in the sun on the deck of the big ship to melt so they could drink their water.

We were much more than their tired eyes could count, not ninety-seven but thousands, an ice field as far as the eye could see.

We were a whole population.

1Through the Looking Glass

A painter and a priest are standing at the rail of a steamer, the Merlin, on the way to the coast of the island of Newfoundland. They had left the port of Halifax, Nova Scotia, in the middle of June 1859 and are making their way to one of their destinations, Saint John. Having reached the foot of Cabot Tower, they meander north of the Avalon peninsula, between the Gulf of St Lawrence and Fogo Island, an area where strangely shaped blocks from Greenland are drifting. After about ten days, they embark on a chartered schooner called Integrity and sail towards the Labrador Sea. A rowboat is waiting on deck between the gangways that connect the forecastle and the stern. This will be their way to approach the giants.

Thus begins a chase that lasts several weeks.

A game of hide and seek

They are iceberg hunters.

They are armed with a battery of brushes and pens. Their satchels are overflowing with notebooks and drawing boards. Pairs of telescopic-handled theatre binoculars sit atop crates of paintings. Frederic Edwin Church intends to capture the volumes and colours of icebergs in oil studies and pencil sketches. He has a large work in mind. Louis Legrand Noble, on the other hand, is keeping a chronicle of their expedition. He wants to write a truthful account of it. The two friends play cards with other passengers. They reminisce, discuss the colour of the water and squint at the sky to judge the weather. They wait for the moment when they can see the faces of the ‘islands of ice’, as Captain Cook called them, up close. They are on the lookout, as eager as trappers, for an unusual catch. They are on guard, day and night, sleep poorly and flinch at the slightest sign. The swell makes their stomachs groan.

They made inquiries before leaving. They know that icebergs are a sailor’s nightmare.

For the past ten years or so, the northern latitudes have been the focus of attention. HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, the two warships that Sir John Franklin commanded in 1845 in an attempt to open the Northwest Passage, have been lost. Jane Griffin, otherwise known as Lady Franklin, moves heaven and earth to find her husband. She convinces the British Admiralty to mount several search expeditions. Other governments quickly follow suit. The physician and explorer Elisha Kent Kane publishes two first-person accounts of the campaigns organised by the American businessman and philanthropist Henry Grinnell. His descriptions of desolate Arctic landscapes provided a stock of images that inspired an entire generation.1

Everyone wants to know what happened to Franklin. Significant economic and political interests come into play. Curiosity becomes bankable. Public opinion is intoxicated. A nation’s reputation depends on this desire to know. But the research stalls. Until the mystery suddenly becomes clearer. In the spring of 1859, Francis Leopold McClintock, a regular member of the Royal Navy, and his officers collect evidence from an Inuit tribe on King William Island. They add more evidence and eventually find scraps of clothing, guns, bodies, a cairn, a small tent and a tin box on the ground with a clear message: the two ships had been icebound on 12 September 1846 and Franklin had given up the ghost on 11 June 1847. After this fatal winter, the survivors had decided, on 22 April 1848, to set out on a journey over the ice pack in an attempt to reach more hospitable lands. No one returned.2

Apart from a few minor scares, Church and Noble’s journey goes off without a hitch. The skies are clear, the sea is friendly. One fine day, the deckhand calls out: ‘Icebergs! Icebergs!’ Relief and euphoria: their goal is in sight. The passengers move towards the bow. Two elegant masses of unequal size emerge. The ship is slowly approaching the bigger one. The companions’ eyes widen. But a thick fog starts to spread. Clouds fall over the sea like a stage curtain. They cover the horizon and the show comes to an end. Having their final act taken away, the travellers are disappointed, almost offended.

During a stopover on land, fishermen explain to them that iceberg hunters must be patient. It is always a game of hide and seek. In this game, the roles are unequal and the rules are constantly changing. Icebergs know the winds and currents better than humans. They are mischievous and do not let themselves be caught. They disappear as suddenly as they reappear. If you get too close, they run away or get angry. They are more intelligent than their pursuers.

The icebergs have made a pact of friendship with the fog. No one can break it. When the clouds transpire, water droplets become ice crystals that pile up on top of each other. Then these crystals return to the clouds as they evaporate. In the meantime, the blocks take advantage of the moments when the air becomes thick with moisture to escape from view. Icebergs and mists unite the sky and the sea. Their relationship is mutual. Each partner benefits. By way of encouraging them to turn back, the fishermen tell our two dilettantes a secret worthy of the best pirate stories: ‘No jackal is more loyal to its lion, no pilot fish to its shark, than the fog to its berg.’3 A chill runs down Church and Noble’s spines: they understand that, in such reciprocal living pairs, the iceberg is the predator. Mists follow it everywhere. They are inseparable.

At the beginning of July 1859, a group of thirteen icebergs encircles the schooner. The painter and the narrator are ecstatic. They will finally be able to examine them closely. The boat is lowered. With the necessary care. When icebergs roll over, they take everything with them in their chaotic movements and cause panic around them. Sections of ice can collapse and crush the boat. The captain on board orders the rowers to keep a respectable distance.

For several minutes they make their way through the floating masses, taking advantage of a clearing in the sky and a calm sea. They hear all kinds of creaking noises. Intrigued, they turn around this group, whispering incomprehensible words. The reverend fills in his notebooks. He describes the electric murmur of the wind, the sounds of the water carving the walls, the countless plays of light. The show reinforces his conviction that nature is not monochrome but ‘polychrome’. Church, for his part, paints one gouache after another with a precision that belies the low swell.

Icebergs are multifaceted. They are always changing their appearance. So much so that Noble has the feeling that he’s seeing more than one iceberg when he walks along one of them. The first two bergs of a few days earlier had already captivated him. His imagination had been fired: he had seen the tent of a nomadic people in the thinnest iceberg and the vault of a greenish marble mosque in the thickest. It was as if there were secret correspondences between deserts of ice and deserts of sand. Then the masses disappeared in silence. The narrator had not even heard a sound as they fled.4

Among the icebergs, Noble experiences a kind of joyful stupor, like a deep empathy with another being. It is the joy of the ‘Indian’ faced with a deer, the unprecedented happiness of finally finding a ‘wild’ world. He no longer knows which metaphor to choose. One after another, he makes out Chinese buildings, a Colosseum, the silhouette of a Greek Parthenon, a cathedral in the early Gothic style, and the ruins of an alabaster city. Icebergs are great imitators. They recapitulate the history of world architecture with disconcerting ease. The Arctic Ocean becomes an open-air art gallery, a sanctuary of human creativity. Icebergs also summarise geological history. They evoke natural landforms located in the four corners of the globe. Sometimes they resemble ‘miniature alpine mountains’, sometimes the eternal snows of an Andean massif that the ocean has submerged. At this point in the story, Noble assures his readers that he and his painter friend share the views of the famous geographer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt had just died in Berlin. He had spent his life establishing that the ‘cosmos’ is unified in all its parts.

This episode with the group of icebergs changes the fate of our narrator. Nothing is really the same any more. The rest of the journey is a chaos of images. The more he crosses paths with other behemoths, the more Noble forges new ones to illustrate the encounters: a warship with pointed cannons and a sharp bow, ivory carvings, clouds depicting the faces of poets, philosophers or polar bears. He describes caves, niches, balconies and escarpments. He guesses that the icebergs cast a melancholy gaze on the ship’s passengers. He is saddened by the way some are obviously fragile. Meanwhile, on deck, Church finishes his preparatory oil studies. Then, in his cabin, he pencils a few sketches on the pages of a small notebook and carefully arranges his boxes.

Framing icebergs

Two years after their return, the painter unveils an impressive work to the New York public: The North. The painting is 1.64 m by 2.85 m. It is April 1861, opinion was positive, but not unanimous: too much emptiness, no signs of humans. Church reworked his large canvas. He decided, on the spur of the moment, to show it in Europe. In June 1863, an evening for the launching was organised in London. A number of prominent people attended, including Lady Franklin and Sir Francis Leopold McClintock. Observers in the British capital could see a broken mast, still with its masthead, pointing to a boulder on the right. Church added the detail in the final version. No doubt to evoke the tragic sinking of the Franklin and as a reply to his critics. All around the icebergs there is the same veiled Arctic glow. The painter renamed his work with the title it still bears: The Icebergs.

What reading can we give this painting?

A text printed on a sheet of paper was distributed when it was presented, in 1862, at the Athenaeum in Boston. In it, the artist explains his choice of perspective. He addresses the audience:

The spectator is supposed to be standing on the ice, in a bay of the berg. The several masses are parts of one immense iceberg. Imagine an amphitheatre, upon the lower steps of which you stand, and see the icy foreground at your feet, and gaze upon the surrounding masses, all uniting in one beneath the surface of the sea. To the left is steep, overhanging, precipitous ice; to the right is a part of the upper surface of the berg. To that succeeds a inner gorge, running up between alpine peaks. In front is the main portion of the berg, exhibiting ice architecture in its vaster proportions. Thus the beholder has around him the manifold forms of the huge Greenland glacier after it has been launched upon the deep, and subjected, for a time, to the action of the elements – waves and currents, sunshine and storm.

Figure 1 Frederic Edwin Church, The Icebergs (1861–3), Dallas Museum of Art

Church trains the viewer’s eye by detailing aspects of the scene. He believes that the audience needs this. For at least two reasons. On the one hand, the iceberg is a spontaneously pictorial object. But the variety of its lines must be shown. Otherwise, the viewer risks becoming bored with so much uniformity. On the other hand, the beauty of the iceberg is intriguing. The proportions of the iceberg throw Archimedes’ principle into doubt. The mass seems very heavy. And yet it floats! It is so light, almost airy. How can the combination of weight and weightlessness be represented?

The painter has observed the bergs closely. He knows that their plasticity is a challenge. Their straight lines intertwine and their curves overlap. The icebergs constantly alternate foregrounds and backgrounds. They compose volumes that seem eternal. Then they dissolve into the air and the ocean. The massive ice cubes metamorphose into small balls of volatile flakes.

Church wants to control these ambivalences. He directs the gaze into a well-defined space. Better still, he plays with the frame, making the ice occupy three sides of the painting. He freezes the icebergs in their materiality and makes a stationary image from an inanimate, hieratic world that is ice in every direction, except for on high, where it opens onto a horizon tinted with the sun of a peaceful late afternoon. This framing of ice by ice, saving one side for the source of the light, has only one purpose: to make the spectators understand that the real texture of icebergs is that of light. In the eyes of the painter, it is light that reshapes the forms.

A boulder can be seen on the right-hand side of the painting. This is not an aesthetic whim. The art historian Timothy Mitchell has shown that Church was taking a stand in a scientific controversy between Louis Agassiz and Charles Lyell from 1845 to 1860. The debate between the two scientists centred, among other things, on the exact nature of ‘erratic’ rocks and the role of icebergs.

Agassiz defended the thesis of an ancient global glaciation in his famous Études sur les glaciers and several other lectures. During a primordial ‘ice age’, the Earth was covered, and the so-called erratic boulders, which often adorn the sides of glaciers, were signs of this. Lyell proposed another theory in his no less famous Manual of Elementary Geology. On several field trips he had examined many deposits on shore that came from beached icebergs. He deduced that these alluvia corresponded to the rocky conditions of the continents. His opinion was that part of the Earth, including the North American plate, had not been covered by ice but, rather, submerged. Then as the water had receded, the continents reappeared and the icebergs had carried boulders from the land. The ‘floating mountains’ solved the riddle of rocks scattered far from any ice mass.

Lyell’s hypotheses influenced many explorers. They looked for evidence that icebergs carried pieces of rock. By the 1860s, however, empirical evidence confirmed Agassiz’s arguments. His rival eventually abandoned his theories of iceberg ‘rafts’.5

Church’s painting has gone through several versions and many variations. Long forgotten, it is now a much prized work. It is not only a tribute to Franklin and the strange beauty of ice, it is a nod to a geological argument about the Ice Age. Off the coast of the island of Newfoundland in the summer of 1859, Noble saw icebergs as the monuments representing the whole world. The artist painted his canvases imagining that these sublime masses carried the debris of a once sunken planet.

The reign of the sublime

Church went north with a mind full of books. Like most of his contemporaries, he was aware of travelogues and scientific writings. But at the forefront of his thinking were the now popular reflections of Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant on the sublime. In these theories of the previous century, the canonical examples are those of a mountain whose snowy peak pierces the clouds, of a storm breaking, or of a storm seen from the shore. The fictional viewer experiences a paradoxical feeling of a fear of dying while remaining in safety. All five senses warn one of the risks. At the same time, one feels infinitely free. One’s reason finds strength in confronting an idea of the absolutely immense, even of the unlimited. At a safe distance, one might assume that one’s life is not really in danger.

These ideas were widely disseminated among the international community of polar explorers. Confronted with icebergs, everyone feels the same contradictory emotions as those described by philosophers when faced with raging waves, lightning in the sky or alpine snow. Adventurers are both terrified and amazed, overwhelmed and exhilarated. They rediscover their dual nature as sentient and spiritual beings. They feel both fragile and powerful, both mere mortals and true demiurges. In Church and Noble’s time, the spectacle of the iceberg was already over-coded by theories of the sublime.

Another argument recurs in this interpretive framework: titanic forms bear the imprint of a higher principle. Kane described the Arctic as ‘a landscape such as Milton or Dante might imagine – inorganic, desolate, mysterious’. He was careful to add: ‘I have come down from deck with the feelings of a man who has looked upon a world unfinished by the hand of its Creator.’ The spectacular appearance of the icebergs is a reminder of the humble condition of humans. The drifting boulder is ‘one of God’s own buildings, preaching its lessons of humility to the miniature structures of man.’6 The theme is an old one. Long before the beginnings of polar exploration, the iceberg was seen as a work of providence.

We are in Ireland, in the sixth century.

A monk tells another monk about his voyage in a stone trough, as in the legends of the Breton saints. He evokes a remote, isolated and magical island. All shrouded in fog, it is hidden from inquisitive eyes and unvisited by storms. On this land, nothing happens as elsewhere: nature is luxuriant, time slows down, no one feels any material need. Faced with so many marvels recounted by his own godson, Mernoc the monk, Brendan de Clonfert decides to make the same journey. After months of meticulous preparations, he and his fourteen companions embark on a small boat made of wood and leather. They set off towards the Northwest in search of paradise.

In their frail curach, the pilgrims huddle around the single mast. The voyage is full of hazards and miracles. They come across birds singing divine hymns and drink sleeping potions. They inadvertently cook meat on the backs of gigantic dormant fish and are attacked by sea monsters.

One day, a crystal pillar appears. It seems very close, yet it takes them three days to reach it. When Brendan looks up, he cannot see the top of the transparent pillar, which is lost in the sky. Gradually, other pillars appear. At the very top, a huge platter sits on four square legs. A sheet with thick, undulating mesh as far as the eye can see envelops it. The monks think they are looking at an altar and a tapestry. They tell themselves that this is the Lord’s work.

Brendan notices a gap where their boat could slip through. He orders his companions to lower the sail and mast. They gently row into the crevice and find themselves inside a huge reticular mass. Corridors stretch out endlessly. The colours in the walls are shimmering, changing from green to blue. Shades of silver sparkle. Their fingertips graze a material that feels like marble. At the bottom of the water, they see the ground on which the diaphanous block rests. The sun is reflected in it. There is bright light, inside and out. Brendan takes measurements. For four days they calculate the dimensions of the sides. The whole thing is several kilometres and as long as it is wide. The pilgrims can’t believe it.

The next day, they discover a flared bowl and a golden plate adorning the edge of one of the pillars. Brendan is not surprised. He places the chalice and paten before him and begins to celebrate the Eucharist. When the ceremony is over, he and his companions hoist the mast and sail. They take hold of the oars and set off. On their return journey, they are carried by favourable winds that bring them home without incident.7

Brendan’s epic was copied hundreds of times between the ninth and the thirteenth century, a real bestseller. Today’s commentators believe that the travelling monks saw an iceberg floating off the coast of Iceland. They would have entered the straits where icebergs calve off the coastal glaciers of Greenland.

At the time Church and Noble were travelling, icebergs were, in the European imagination, sometimes the ancestors of a geological age, sometimes creatures in the service of a sacred history. In both cases, they are icons of the sublime. Our narrator and the painter are not the only ones to see ‘floating mountains’ in the ocean, or cathedrals, ruins of lost cities, winding avenues, and sometimes even the face of the Creator. When ships are icebound, there is plenty of time to observe the landscape, and at such moments the romantic mind opens its toolbox and chooses the most expressive aides.

Thomas M’Keevor served in 1812 as the physician for the Selkirk settlers in the Red River Colony in Canada. In a short travelogue, he expresses his fascination for the icebergs adorning Hudson Bay. Some of them, he wrote,

bear a very close resemblance to an ancient abbey with arched doors and windows, and all the rich embroidery of the Gothic style of architecture; while others assume the appearance of a Grecian temple supported by round massive columns of an azure hue, which at a distance looked like the purest mountain granite . . . The spray of the ocean, which dashes against these mountains, freezes into an infinite variety of forms and gives to the spectator ideal towers, streets, churches, steeples, and in fact every shape which the most romantic imagination could picture to itself.8

This description is already in the style of Louis Legrand Noble! It shows that icebergs have been perceived, in the Western world, as a real production in the amphitheatre of the most unbridled reveries. We all have the faculty of imagination in common. The five Labrador Inuit shown around London by Captain George Cartwright in 1772 thought St Paul’s Cathedral was a mountain. They mistook the bridge over the Thames for some kind of stone structure. Those from Avannaa who landed with the explorer Robert Peary in New York in 1887 were struck by the resemblance of the first skyscrapers in Manhattan to icebergs. Each, in its own way, mixes ‘the natural and the architectural’.9