21,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

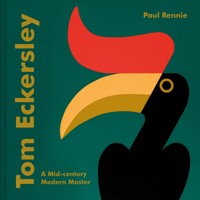

An overview of the work of 20th-century graphic design icon Tom Eckersley – packed with hundreds of his instantly recognisable designs. From iconic posters for the Post Office and London Transport to designs for brands such as Guinness, this richly illustrated book explores the work of influential British poster artist and design teacher Tom Eckersley (1914–1997). Part of the 'outsider' generation that transformed graphic design in Britain in the mid-century era, Eckersley's instantly recognisable posters have become true icons of 20th-century style. Here, design writer and former Eckersley archivist Paul Rennie gives a fascinating exploration of Eckersley's life and work, from his Northern upbringing and early career, through pioneering work during the Second World War, to his central role in mid-century graphic design in the decades that followed. Over 200 designs from throughout Eckersley's career are featured. Made in his signature style combining bold, bright colours and flat graphic shapes, there are designs for clients such as the BBC, British Rail, Keep Britain Tidy, Gillette, BP and Shell. The book also examines Eckersley's position at the forefront of the explosion of print culture in the 20th century, how he helped to transform design education in Britain, and the lasting legacy he left behind. A celebration of a true mid-century modern master, this is the first book on Tom Eckersley of its kind and will appeal to anyone interested in graphic design and visual communication.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 218

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

National Business Calendar Awards (detail), 1983

Eckersley Archive, LCC

For Karen

Contents

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 North-westernismThe Modern Machine-ensemble and Manchester, the Great City of Progress

Dissent, Design and Progress

The Modern Machine-ensemble

The Making of Manchester (a grand city of progress)

North-western Dissenting Radicalism

CHAPTER 2 Early YearsIllness and Reading, and Drawing

Salford School of Art

Paul Nash (1889–1946)

Edward McKnight Kauffer (1890–1954)

Adolphe Mouron (Cassandre) (1901–68)

CHAPTER 3 London and the 1930sA Network of Patronage

Patrons of the Poster

Other Work

CHAPTER 4 1940sCrisis and Compatriots

The RAF

Safety and Industrial Production

Post-war RoSPA

The Wartime GPO

The Post-war Environment

Gillette

Book Illustrating

Ealing Films

CHAPTER 5 1950sInternational Colleagues and Outlook

Alliance Graphique Internationale

Poster Design, 1954

The Design Research Unit and Mass Observation

Artist Partners

London College of Printing (LCP), Back Hill

CHAPTER 6 1960sModern Design and Modern Life

Teaching in the 1960s

Design Work in the 1960s

1960s Poster Design

CHAPTER 7 1970s and BeyondRetirement and Reputation

Work for London Transport, 1970s and Beyond

Valedictories

Design Legacies

AppendixVisual Communication, Economy, Social Progress and Intelligence

Colour Lithography

The Lithographic Poster in Modern Life

Photo-mechanical and Offset Reproduction

The Offset Poster and Modern Life

Post-war Printing

The Ideas Poster

Power: Position, Scale and Point of View

Flat Colour

Sparkle and Pattern

Economy

How Posters Survive

Poster Sizes

Bibliography

Thanks

Index

Picture credits

Introduction

TOM ECKERSLEY was a distinguished member of an ‘outsider’ generation that transformed graphic design in Britain. As a graphic designer and poster artist, he also contributed personally to the explosion of visual print culture in Britain during the twentieth century. During the 1950s and 1960s Eckersley helped to transform design education in Britain. At precisely the time when the visual economy was growing, he was instrumental in providing a greatly expanded form of design formation, and to a great many more students. This produced a cascade effect that impacted directly on British people’s lives, through the experience of new forms of communication and the elaboration of attractive new ideas and lifestyle choices, made visible.

The social changes of the late 1960s, combining counterculture and consumerism, were projected through the new print economy of colour-illustrated magazines, picture books and posters, and also, increasingly, through television. The image culture of the 1960s, presented in larger scale and in colour, helped forge a new optic for the late twentieth century. The new vision helped transform the perception of Britain in both local and international terms.

Today, we take the presence of intelligent communication design for granted. But it’s worth remembering that it wasn’t always like that. Tom Eckersley helped to establish the templates for intelligent and modern graphic design in Britain. One of the criticisms levelled at design, by the cultural commentator Peter York for example, is that designland has a tendency to speak to itself. Eckersley’s work was always public-facing and was characterised by modernist economy (always conforming to the idea that less is more) leavened through the expression of a typically English sense of humour. The combination of a modernist sensibility with a light touch is well worth celebrating in itself.

The circumstances of twentieth-century economic transformation, political hiatus and conflict created a context in which the expanding print economy and the emerging practice of graphic design became increasingly appealing to creative sensibilities. Not surprisingly, the emergence of this new form of cultural production was attractive to outsiders who had previously felt excluded from the longer-established parts of the creative economy.

Nowadays, the émigré contribution to British design after the Second World War is acknowledged and well documented, and rightly so. Tom Eckersley was from another outsider group: northern, working class, and Chapel. Today, these traditions can seem historically remote, at least in contrast to the émigrés who arrived as modernists in the 1930s. The old-fashioned combination of a work ethic and the values exemplified by Eckersley’s background played out through the specific development of design in Britain until the 1980s at least.

Tom Eckersley was from a north-western and Nonconformist background. This combination of geography and values provided a powerful motive for a form of design that derived from the blending of dissent and progress. Luckily for Eckersley, he found colleagues that shared this idealism.

Tom Eckersley sustained a career in graphic design for more than fifty years. His career began at a time when the term ‘graphic design’ was hardly used or recognised, and continued until the beginning of the digital era. Eckersley’s success was testimony, against a backdrop of twentieth-century upheaval, to both his talent as a designer and to his personal resilience; and also to the qualities of his personality. The achievement of sustaining a career in a newly emerging part of the economy against a background of rapidly changing technological change should not be underestimated.

Along the way, Eckersley produced a body of work in posters and graphic design for different organisations that amounts to one of the most substantial and sustained achievements in the history of British graphic design. The first objective of this book is to share his work with a wider public.

Eckersley was a designer who was certainly recognised in his own lifetime. He received various awards and was elected to both international and domestic design associations. Eckersley posters appeared in the specialist design press from the late 1940s onwards and were featured in important exhibitions at home and abroad. This book acknowledges Eckersley’s significance in the development of British graphic design and aims to account for the different strands of his work and to present it within the specific contexts that sustained it.

I was always aware of Tom Eckersley. As someone who was interested in the historical development of graphic design in Britain, I recognised his name as one that recurred, at intervals, from the 1930s through to the 1970s. Indeed, I was conscious of seeing Eckersley’s work displayed on the platforms of London Underground in the 1970s and 1980s. When I began to take a more serious interest in graphic design and poster history, I was fortunate to meet him on a number of occasions, most notably when I interviewed Eckersley and his contemporary Abram Games for a Dutch poster magazine in the early 1990s.

Portraits of Tom Eckersley

Eckersley Archive, LCC

Later, I began a project that examined the industrial safety posters produced by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) during the Second World War. I started by looking at a number of posters designed by Tom Eckersley for this campaign and it turned out that he had been one of the principal personalities involved in guiding this venture. In 2016, the academic work that I had begun on safety posters was presented as part of RoSPA’s centenary celebration. It’s fair to say that, looking back over the last thirty-odd years, I seem to have always been writing about Tom Eckersley.

His personality was reserved but friendly. I remember that he seemed always to say few words and to choose them carefully. Quite often, he might remain completely silent. He had an independent cast of mind and had resolved, from the first, to work independently. This didn’t mean that he worked in isolation. On the contrary, he combined independence of mind with a friendly and collegiate association with colleagues in Britain, Europe and from around the world. By virtue of his personality, approach and body of work, Eckersley’s career provides a powerful example of how to combine life, work and design.

His reserved personality meant that he guarded his own privacy; the details of his private life are scant and he remains something of an enigma. There are few records beyond those of professional advancement. Nevertheless, the poster images survive. The broad outline of Eckersley’s professional career was sketched out by George Him in 1980 in his introduction to an exhibition at Camden Arts Centre. Elsewhere, there is a partial transcript, compiled by Chris Mullen, of a talk given by Tom Eckersley at Norwich in the early 1980s.

Accordingly, this book is not a straightforward biography rooted in the personal detail of Eckersley’s life; it is more a book that examines a life in design by reference to the changing shape of design in Britain, and by reference to the networks, contexts and communities that nurtured and supported him, and that sustained his practice as a designer. I’ve tried to zoom out and position Eckersley in as wide a context as possible.

The present interest in Eckersley derives from the stylishness of the images that he produced, and in his legacy of a substantial body of work. The poster images seem to have become more contemporary-looking with the passing of time. This suggests that Eckersley was forward-looking and, in design terms, ahead of his time. His work was always recognisable from its combination of a sharp clarity of line and boldness of colour, with a message lightened by humour, combining the better parts of continental modernism with a dash of British quirkiness.

Both Tom Eckersley and Abram Games remained enthusiastic and optimistic about the cultural importance of graphic design. They both retained their belief that design was an intrinsically progressive activity that aimed to make the world a better place, and that good ideas and technique could be combined with precision to communicate in an emotionally engaging way. Both were entirely sanguine about the advent of digital processes in design. Indeed, they believed in the primary significance of ideas and understood, even early on, that the digital would express itself as a continuous stream of poster-style pages, combining images and text.

Until recently the history of British graphic design had remained relatively obscure to anybody who existed outside the industry.

Nowadays, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, we can begin to see that the visual expression of the digital stream combines image, text, sound and movement, but that at its heart remains the powerful combination of efficacy and economy that derives from the poster pioneers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and from the simple combinations of word and image.

Against this backdrop of digital expansion, the interest in vintage posters and graphic design history has never been greater. Indeed, this book is testimony to this present-day cultural phenomenon. Far from consigning the poster to history, the internet has consolidated the form as the source code and wellspring of modern communications. Again, this should make Tom Eckersley’s career in poster design and education more relevant and interesting to those of us living and working within the expanded circumstances of communication design today.

Eckersley’s contemporaries Abram Games, F.H.K. Henrion and Hans Schleger (Zéró) were from Jewish and émigré origins, while Eckersley himself was from a North Country Noncomformist background. This last strand of outsider contribution to design needs a little explanation, and the first part of this story describes the combination of values and enterprise that took the tolerant, outward-facing, liberal and enterprising identity of the north-west of England and applied it to the wider projection of British values.

In addition to presenting Eckersley’s work over the years, the account of his life presented here frames his professional activities within a series of networks of people. The networks evolved and changed over time, the protagonists moved on; but Eckersley found, by virtue of his personality and professionalism, a role at the centre of this exciting story.

The outsider status of these early designers combined with the relatively small scale of the creative economy back then to provide for a specific community of design. It is to Tom Eckersley’s great credit that he was able to move from one network to the next and sustain his career through a number of iterations of the British design industry. Part of this story is about the shift from the patronage of individual artists, associated with the ‘pictures-for-business’ model of commercial art, through to the more technocratic specification of design deriving from the necessities of the Second World War, and to the international and system-based design processes of the 1960s and beyond.

When I began writing about graphic design, I was especially interested in the perceived tension between continental modernism and twentieth-century British sensibilities. I was always surprised that it was possible for people to suggest that there had been, simultaneously, too much modernity in Britain or, at the same time, not enough!

It’s been reassuring over more recent years to see how the specific and different contexts for design have allowed for a wider range of modernisms to flourish locally and to have been more clearly distinguished from each other. It’s natural that, in the first stages of design history, individual personalities are identified as significant and that particular examples of work are signalled as iconic.

We now live in a society defined by a system of structures derived from the standards and consistency of property rights, legal precedent and logic. But we experience all this through feeling.

Design became a process that could provide an interface between this system of logic, in its material form, and our sense of the world through feeling.

It’s a bit peculiar to be thinking, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, about problems that derive from an eighteenth-century systemic antagonism between logic and feeling. We just need to think of ourselves as parts of a long process. The huge development of technology has allowed for communication design to move beyond the confines of the print economy. We are entering a world where, thanks to the combination of technology and ideas, the activities of design combine to help us to begin constructing our own identities.

Five Decades exhibition poster

London College of Printing, 1975

Eckersley Archive, LCC

CHAPTER 1

North-westernism

The Modern Machine-ensemble and Manchester, the Great City of Progress

Editorial illustration

News Chronicle, 1936 (with Eric Lombers)

Eckersley Archive, LCC

Dissent, Design and Progress

The development of the creative economy in Britain has advanced through the alignment of several distinct structures and systems of our society. In this chapter, I want to present a broad-brush account of the historical progress of this positive and constructive alignment. I believe that it accounts for Tom Eckersley’s specific approach to design as humanistic, progressive and as an idealistic expression of human enterprise and effort.

This section proposes an alignment between the traditions of Nonconformism and political radicalism in the north-west of Britain in general and around Manchester in particular. In Manchester, the activities of manufacturing and trading laid the foundations of the modern liberal economy and also supported a form of radicalism that has, in the main, aligned itself with social progress.

The origins of graphic design are not to be found in the ancient languages that combine writing and picture-making. Rather, graphic design has emerged as the visual and technologically enabled expression of a specific set of cultural values that attach to a particular form of social organisation. These values are associated with both the organisation of industrial economy and with the machine-ensemble of modern urban life. The combination of system and progress derives from the emancipatory critique that powered the eighteenth-century philosophical Enlightenment.

The most significant concepts I want to introduce in relation to this developmental trajectory of design are those of the machine-ensemble and of dissent, especially that deriving from religious Nonconformism. The connection between dissent and design is more than one of historical coincidence. The dissenting tradition provided for a powerful critique of the existing institutions and organisations within society, and at the same time pointed towards something different and better.

The Modern Machine-ensemble

Joseph Whitworth, the great nineteenth-century engineer from Manchester, played a crucial role in the successful extension, through the integration of parts, of the Victorian machine age. In 1841 Whitworth proposed a general specification of screw-threads and fixings that became a national standard. Suddenly, the parts began to aggregate into something much bigger.

In the same way, Manchester’s specific combination of liberal values and enterprise spread to a series of satellite towns across the whole of the north-west of England. The agglomeration of towns and cities became a visible manifestation of the nineteenth-century network of the machine-ensemble.

The term machine-ensemble was first coined by Wolfgang Schivelbusch in relation to the nineteenth-century railway system. The term acknowledges the scale, scope and speed of industrial machine integration so that the systemic and mechanical workings of the whole are given expression through this term.

As the term suggests, the machine-ensemble was formed as a group of connected machines of different sorts that each combined to form a network system. The network quickly became more than the sum of its parts and began to work as a meta-machine itself and form the basis for the emergence of a specific logic of machine philosophy.

The first glimpses of the machine-ensemble became evident within the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth century. New inventions greatly increased production while at the same time reducing costs through much-improved labour efficiencies. The standard forms of machine-made parts further advanced these economies and efficiencies by allowing for an increasing interchangeability of elements.

The theatre of machines was quickly recognised as an exemplar of mechanical intelligence. Charles Babbage, the computer pioneer, understood that the physical arrangement of machines could provide for an automatic and logical sequence of productive events. Babbage describes this specific logic in his On The Economy of Machinery and Manufactures (1832). It took some time for the logical consequences of this organisation to become evident beyond the immediate circumstances of workshop and factory. The imposition of standard parts led to the standardisation of working practices and towards a more general co-ordination of elements across civic life.

The machine-ensemble became bigger through aggregation, but as it became bigger it also became faster. We can understand this through the evident acceleration of modern life as evidenced by the speed and stages of foot, horse, railway and internal combustion. Later, there would be jet-powered, solid-state and digital developments. Eventually, fibre optics would see things move at the speed of light.

Each of these technologies provided the basis for a step change, or quantum advance, in the speed and production of everything; including a specific image culture associated with the speed of the ensemble. The integration of elements and the automation of function that was implicit in the machine-ensemble changed the way that people saw and experienced the world. Society produced, at intervals, the new kinds of image culture required to represent the world as it was being experienced.

The modern poster, distinguished by colour, scale and the integration of word and image, provided for a form of communication that could be understood from a distance, at a glance, and while moving. But the speed of the machine-ensemble also changed painting, film, literature and music! In short, the machine-ensemble produced its own image culture to keep pace with the new technology.

It’s worth noting, too, that the image speeds up in several ways: it speeds up as a convincing representation of the acceleration of modern life, and is also produced more quickly through improved technology.

Of course, Manchester wasn’t the only place where these conditions pertained. But the scale and scope of Manchester’s growth, and its long tradition of radicalism, helped to make this alignment more tangible.

The Making of Manchester (a grand city of progress)

Manchester developed in record time, and as a consequence of the accelerated industrialisation of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, officially obtaining city status in 1853. By the 1820s, it was established as a great centre of manufacturing and as the wellspring for a political ideology of liberalism and free trade.

For many observers, the development of modern Manchester was both exciting and appalling. The scale and energy of enterprise was exciting, while the living conditions of workers were frequently squalid. Friedrich Engels visited Manchester during the 1840s and described the living conditions of workers in his The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845). Engels was guided through Manchester by Mary Burns and was able to observe the various horrors of child labour, the despoiled environment and the squalor of its overworked and impoverished workers. The brutality of the system he observed could be recognised in the many people broken as a consequence of unregulated working conditions and industrial accidents. For Engels, as for many others, Manchester seemed a portent of something both wonderful and terrible.

The historian Patrick Joyce has described the development of Manchester in terms of the normative structures, systems and civic organisation of political administration. This, he suggests, provided both the platform and bulwark to support the democratic extensions of the nineteenth-century reform movement. The great experiment combined, in the end, to promote a form of liberal governance and a connected form of specific social identity.

The historical development of Britain’s great provincial cities has been well documented. Manchester, because of its size and success, and because of its association with both Nonconformist dissent and political radicalism, remains the most potent and significant exemplar of the Victorian industrial metropolis and of an expansive ideal of social progress. Asa Briggs and, more recently, Tristram Hunt have both written accounts of the spectacular expansion and growth of Manchester during the Victorian period in Britain.

Manchester grew rapidly from modest beginnings. In the course of the eighteenth century, the town’s population grew several times over. The circumstances of Manchester’s early growth placed it beyond the usual controls of democratic representation. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, its scale and prosperity had begun to demand a closer alignment between the material living conditions of the majority, and the regulatory framework within which they lived.

The emergence, from the beginning of the nineteenth century onwards, of new centres of population beyond the traditional boundaries of parliamentary representation required the reform of both democratic geography and of voting rights. The Great Reform Act of 1832 marked the first step towards redrawing electoral representation so as to take account of this. The Act also increased the number of people able to vote in elections.

The misalignment between the traditional spaces of power and their representation within the democratic process had been made especially evident by the imposition of Corn Law tariffs from 1815 onwards. These tariffs impacted disproportionately upon urban populations such as Manchester. The imposition of these unjustified tariffs on basic foodstuffs was quickly recognised as especially punitive to the energy and prosperity of Manchester. The imposition of tariffs was also understood, from the first, as being both unfair as a matter of principle, and as a flagrant attempt to shore up the prosperity and influence of landowners. Opposition to the Corn Laws was mobilised through the Anti-Corn Law League, established by Richard Cobden in 1839.

The opposition to the Corn Law tariffs soon became generalised beyond the original scope of the campaign to align both middle-class merchants and worker interests within its objectives. Manchester quickly became identified as the de facto centre of these new class interests. The violent suppression of the worker gathering at Peterloo in 1819 had provided an early and tragic testimony to the tensions arising from this emerging struggle for power.

In its early phase, the Industrial Revolution was slightly distant and separate from the London political elite. By the 1830s, the success of the industrialists, their wealth, power and influence, had made them significant for this elite. The northern industrial base was assimilated into the establishment, along with its values of self-help, free trade and co-operation, through the Great Reform Act.

In the end, the scale and dynamism of Manchester turned the city into a powerful symbol of both energy and progress. In political terms, the city became a physical and intellectual manifestation of a liberal, outward-facing and expansive engagement with the world.

Patrick Joyce describes the emergence of Manchester as a symbolic demonstration of a specific form of political economy. The broad streets, straight lines and improved visibility suggested a city where people and goods, and even ideas, could circulate freely and at the required speed demanded by the machine-ensemble. The city became cleaner and better-lit, the modern iteration of the ‘shining city on a hill’.

From the 1840s onwards, the urgent assimilation of the northern cities provided the backdrop for a number of technical and moral standardisations. These were applied to the new social body, identified as representative of the industrial city and of its progressive agenda. These reforms took on a number of different forms and extended beyond Manchester. Among the most significant of these new systems and structures was the advent of a standard time deriving from the railway, and the elaboration of the Penny Post and its attendant developments in relation to street-naming and the concomitant identifying of individuals and addresses. Joyce also describes how the civic growth of Manchester combined elements of both expansion and control. The main streets of Manchester became wider and straighter. It was within this context that the graphic expression of modern life began to be displayed and consumed.

The events at Peterloo (1819), where troops charged a largely peaceful crowd, provide a foundation myth for democratic reform in Britain. The events of 1819 prepared the route towards the Great Reform Act of 1832, and helped to establish Manchester as a city of enterprise and social progress.

The individual freedoms of modern democracy became exemplified by both the physical environment of the city, its panoptic and controlling organisation, and by the social body of its citizens. In short, Joyce suggests a relationship between people and things that is not simply one of practicality and efficiency, but which constitutes the condition of progressive possibility and social potential identified as ‘design’.

North-western Dissenting Radicalism

Looking back at the history of modern design in Britain, it is tempting to imagine that the emergence, during the late twentieth century, of a powerful creative economy has simply been a consequence of Britain’s pioneering first-mover position in relation to industrial organisation. In fact, the origins of design pre-date the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. The philosophical discussion associated with the English Reformation and its aftermath expressed itself freely through speech and through print culture, and the 1640s witnessed an explosion of short-form writing that could be printed economically through letterpress and widely distributed. From the first, the dissenters gave careful consideration to the visual appearance of their printed pamphlets and tracts.