4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

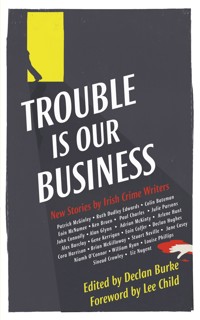

Thrilling, disturbing, shocking and moving, Trouble Is Our Business: New Stories by Irish Crime Writers is a compulsive anthology of original stories by Ireland's best-known crime writers. Featuring: Patrick McGinley, Ruth Dudley Edwards, Colin Bateman, Eoin McNamee, Ken Bruen, Paul Charles, Julie Parsons, John Connolly, Alan Glynn, Adrian McKinty, Arlene Hunt, Alex Barclay, Gene Kerrigan, Eoin Colfer, Declan Hughes, Cora Harrison, Brian McGilloway, Stuart Neville, Jane Casey, Niamh O'Connor, William Ryan Murphy, Louise Phillips, Sinéad Crowley, Liz Nugent. Irish crime writers have long been established on the international stage as bestsellers and award winners. Now, for the first time ever, the best of contemporary Irish crime novelists are brought together in one volume. Edited by Declan Burke, the anthology embraces the crime genre's traditional themes of murder, revenge, intrigue, justice and redemption. These stories engage with the full range of crime fiction incarnations: from police procedurals to psychological thrillers, domestic noir to historical crime – but there's also room for the supernatural, the futuristic, the macabre. As Emerald Noir blossoms into an international phenomenon, there has never been a more exciting time to be a fan of Irish crime fiction.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

TROUBLE IS OUR BUSINESS

TROUBLE IS OUR BUSINESS

Edited by Declan Burke

Foreword by Lee Child

Trouble Is Our Business

First published in 2016 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Foreword © Lee Child, 2016

Editor’s Introduction © Declan Burke, 2016

Individual Stories © Respective authors, 2016

The authors have asserted their moral rights.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-563-9

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-564-6

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-665-3

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2, Ireland.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Foreword by Lee Child

Editor’s Introduction by Declan Burke

Patrick McGinleyA Doctor in the Making?Ruth Dudley EdwardsIt’s Good For YouColin BatemanThe Gaining of WisdomEoin McNameeBeyond the Bar, WaitingKen BruenMiller’s LanePaul CharlesIncident on ParkwayJulie ParsonsKindnessJohn ConnollyThe Evenings with EvansAlan GlynnThe CopyistAdrian McKintyFivemiletownArlene HuntThicker than WaterAlex BarclayRoadkill HearGene KerriganCold CardsEoin ColferA Bag of HammersDeclan HughesThe Time of My LifeCora HarrisonMara’s First CaseBrian McGillowayWhat Lies InsideStuart NevilleThe CatastrophistJane CaseyGreen, Amber, RedNiamh O’ConnorCrushWilliam RyanMurphy SaidLouise PhillipsDoubleSinéad CrowleyMaximum ProtectionLiz NugentCruel and UnusualForeword

by Lee Child

Generally I’m wary of national stereotypes, but experience and observation have proved a few things true: the French are great cooks; the Italians make great coffee; the English can’t play tournament soccer; and the Irish are great storytellers.

Some Irish people don’t like to hear that. Some say using the word ‘storyteller’ rather than ‘novelist’ demeans them by focusing on an earlier, primitive, oral tradition. I say that’s a distinction without a difference. For about a hundred thousand years all storytelling was oral. Mass literacy and mass-market printing are very recent. If the history of human narrative was an hour long, then novels as we understand them are about five seconds old. The newer tradition was born of the old, and has deep roots there. Novelists are oral storytellers, at a temporal remove: not face to face and contemporaneous, but later, with the printed text acting as a crude audio recording. The two traditions are inseparable. The Irish are good at both. I can pick up an Irish novel and feel the same warm, anticipatory glow as I do when sitting in a pub and watching an Irish friend’s eyes light up as he launches into a long and convoluted tale.

Why? Obviously there are reasons. They can’t be based on literal DNA, because all humans share the same basic genes. I think they’re based on a kind of cultural DNA. Like French cooking: it’s the penultimate stage in a precious and well established ritual, that starts with daily shopping for locally grown artisanal ingredients, which by dint of stubborn tradition remain largely organic and unadulterated. Typically the cook lets the best available ingredients dictate the recipe, rather than vice versa. The actual stove-top work is one component among others, all of which collectively guarantee the quality of the result.

Same with Irish storytelling, I think. Whether writing or speaking, an Irish storyteller leans in and begins with a certain kind of aplomb that seems to come from a certain kind of confidence: he seems to assume he’ll get a fair hearing. Because storytelling is a two-way street. It’s a transaction. First a story is told or written; then it’s heard or read; then it exists. The better it’s told or written, the better it will be; but also, and crucially, the better it’s heard or read, the better it will be.

The Irish are great storytellers because the Irish are great story-listeners.

Irish writers start with that knowledge. Sure, if they’re boring, eventually they’ll be ignored. But they’ll get a fair shake first. That breeds confidence. They can relax. Nothing needs to be rushed. A little patience is permissible. The basic transaction is underwritten by cultural DNA. It’s a virtuous circle.

The proof is in this collection. Trust me, these writers are saying: Give me a minute or two, or a page or two, and I’ll give you a story. And what stories they are. The mutual agreement between writer and reader produces organic tales, going where they need to go, free of anxiety, free of nerves. It’s a glorious, spacious, permissive ritual, and long may it last.

Lee Child

New York

2016

Editor’s Introduction

I was very pleased, of course, when Dan Bolger invited me to curate a collection of crime stories for New Island. Roughly two decades on from when a number of writers – Patrick McGinley, Colin Bateman, Ruth Dudley Edwards, Eugene McEldowney, Eoin McNamee, Hugo Hamilton, Joe Joyce, Jim Lusby, Vincent Banville, Julie Parsons, John Connolly, Ken Bruen – began regularly publishing crime fiction and mystery novels, it seemed a good time to celebrate Irish crime fiction.

About five minutes after agreeing to do so, however, the doubts set in. The first had to do with who to include – or, more pertinently, who could be left out (a few omissions were unavoidable, in that some novelists simply don’t write short fiction, some writers were so tied to deadlines that they were unable to contribute, and some of the earlier practitioners are no longer publishing). A collection featuring twenty writers, we felt, would suffice to provide a timeline from the 1970s to the present day, to give a sense of the progression and evolution of Irish crime writing. Naturally, we were wrong. The number of writers publishing under the Irish crime fiction banner has mushroomed dramatically, especially in the last five years, and it immediately became clear that we could not include every writer who deserved to be represented. Any collection such as this invariably gives rise to the ‘But what about . . . ?’ question; it goes with the territory. Unfortunately, had we included every writer we would have liked to include, the book could easily have ballooned to twice its current size. If your favourite writer isn’t to be found here, we beg your indulgence.

Another doubt revolved around whether there is actually such a beast as ‘Irish crime fiction’. Some of the best-known Irish crime writers weren’t born in Ireland; others have yet to set a novel in Ireland; some began by setting their stories elsewhere before choosing Ireland as a setting, while others have moved in the opposite direction. Indeed, ‘Irish crime fiction’ is probably a little too diverse for its own good, at least for the purpose of definition (or, as it’s known in publishing, ‘marketing’): it encompasses thrillers and private eye stories, urban noir, who- and why-dunnits, psychological thrillers, police procedurals set at home and abroad, cosy crime, historical mysteries, conspiracy thrillers, comedy crime capers, domestic noir, spy novels … In other words, ‘Irish crime fiction’ is a very broad church, and grows broader by the year, to the point where attempting to impose a definition would be virtually meaningless. And yet here we are, with Irish authors merrily ignoring any attempt to corral them into any definition and by now firmly established as best-sellers, prize-winners and ground-breakers on the international crime fiction stage …

Further complicating the issue (in a good way, we hope) is that the remit offered to the contributing writers was something of a blank slate – all we asked for was a short story, without specifying that it should be a crime or mystery story. Some writers responded with a traditional crime/mystery, others with stories radically different from their previous work, or offering an unexpected variation on the traditional crime/mystery story, while others sent stories that couldn’t be considered crime/mystery at all. Trouble Is Our Business, then, isn’t so much a collection of Irish crime fiction stories as it is a collection of stories by Irish crime fiction writers, which I’ll cheerfully admit was something of a relief: I was dreading the idea of editing an entire collection of stories in which Inspector O’Plod tries to discover who murdered whom in the library with the shillelagh …

Finally, a word on gender. One of the most notable trends in Irish crime fiction over the last five years or so has been the way women have come to dominate the number of debut Irish crime novels being published. Very few women feature in the first half of Trouble Is Our Business, but women outnumber men in the later stages of the collection (a fact reflected in the fact that the past four winners of the crime fiction gong at the Irish Book Awards have all been women). The reasons why are beyond the scope of this collection, but along with the emergence of a generation of Northern Irish crime writers engaging with ‘the Troubles’ or the ‘post-Troubles’ landscape, it’s the most exciting development in the current incarnation of Irish crime writing.

Declan Burke

May 2016

Patrick McGinley

Several of Patrick McGinley’s novels (e.g. Bogmail, Goosefoot, Fox Prints) occupy an ill-defined place somewhere on the periphery of the crime genre. Bogmail, first published in 1978, was nominated for an Edgar and received a special award from the Mystery Writers of America. Patrick was born in Donegal in 1937 and was educated at Galway University. He moved to London in 1962 to pursue a career in book publishing. He now lives in Kent with his wife Kathleen. His latest novel, Bishop’s Delight, is published by New Island. His favourite detective novel is E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case. His favourite crime story is Roald Dahl’s Lamb to the Slaughter.

A Doctor in the Making?

‘Telephone engineer,’ he said solemnly.

To judge by his manner he could have been a solicitor or even a doctor, though he looked too young to have qualified as either. Tall and fresh faced, he wasn’t what she’d call handsome. He was what Melanie, her flatmate, liked to call ‘a middling man’. She led the way into her office and pointed to her desk telephone and computer.

‘No matter what number I dial, I get the same response,’ she explained. ‘“The number you have dialled has not been recognised.” I can’t send or receive emails either.’

He picked up the receiver, dialled a number, and listened.

‘It’s probably a faulty connection,’ he said as if to remind himself. He was obviously not a talker. Probably one of those men who communicate from behind an invisible screen. Melanie knew about men; she ‘collected’ them as you might collect butterflies. She would be interested to hear about this latest specimen of what she called ‘the problematical sex’.

He opened his tool bag and rummaged through an assortment of screwdrivers, flex and electronic gadgets. He tested the connections to what he called the router. Next he opened the junction box and then the socket and terminal in what she could only describe as willed silence. Still, she watched him at work because she liked to find out for herself how things related one to the other. Now and again she asked a question, to which he replied without pausing to look at her.

The thought occurred to her that perhaps he felt shy with young women. Melanie said that some young men open up to middle-aged women more readily than they do to women of their own age, but then Melanie had her own view on everything. She said that electricians, plumbers, and boiler men in particular like to wrap themselves in mystery as if they were some sort of secular priesthood without the grandeur of robes or vestments.

‘None of the connections is at fault,’ he said as if delivering a hard-won diagnosis.

‘So what can it be?’ She felt pleased that finally he had spoken without being prompted.

‘It can only be the wiring.’

He inspected every room in the flat, including both her bedroom and Melanie’s, tracing the path of the wiring and examining Melanie’s computer and micro-filter. Wherever he went, she followed, because she felt that she should keep an eye on him. To soothe any feeling he might have of being monitored, she began telling him all sorts of tittle-tattle about Melanie, about how she and her boyfriend were keen bridge players, for example. Melanie was so bright that her boyfriend was worried he might lose her to some clever dick from Trinity, where she worked in administration.

At eleven she gave him tea and two chocolate biscuits. When she asked if he took sugar, he said, ‘No sugar, just a dash of milk.’ That surprised her because Melanie claimed that all workmen took three spoons of sugar in their tea with lashings of milk. It had become obvious that he was no ordinary workman. Earlier she had spied a book protruding from the pocket of the anorak he’d draped over the back of a chair – having first asked for her permission. She concluded that he’d had a good upbringing and liked to give the impression that he was something of a gentleman.

‘Sections of the wiring are old and defective,’ he said. ‘I’ll have to replace them, I’m afraid.’

‘These flats were once part of a Victorian mansion. Very likely some of the wiring may be up to eighty years old.’ She felt pleased that at last she could offer an intelligent comment relating to the work in hand. She had no wish to leave him with the impression that she was yet another dumb blonde. It was now 12.30, and she was seized by an idea that gave her a sense of largesse.

‘What do you do for lunch?’ she asked.

‘I work through my lunch hour so that I can knock off early.’

‘I’ll prepare a light snack for us both,’ she said casually. ‘That is, if you don’t mind.’

Since he did not respond one way or another, she went to the kitchen and put a quiche in the oven to heat up. Half an hour later she brought him half the quiche with a glass of Chablis, thinking that perhaps he’d never had Chablis with quiche before, and that the combination would surprise him. When he thanked her and said he’d eat while he worked, she insisted that he join her at the small round table in the living room.

‘I can see you’re a reader,’ she smiled. ‘I spotted a book sticking out of your jacket pocket.’

‘It’s my favourite book, the story of a young man called Gregor Samsa who woke up one morning to find that during the night he had turned into a monstrous beetle.’

‘Sounds positively revolting.’

‘But it’s true. I would even say that it is the truest story ever told. You see, it has layer upon layer of meanings, so many layers that no one reader can ever hope to exhaust its range of possibilities. I have now read it fourteen or fifteen times and I still haven’t come to the end of its wealth of suggestion. At times I feel that what I need is a kind of literary potentiometer to measure its full potential.’

‘You’re not a professor on sabbatical, by any chance?’

‘Oh, no, I haven’t read enough unreadable books to qualify as a professor. I just keep reading and rereading the same handful of books over and over again.’

‘So you’re a specialist then, reading deeply rather than widely?’

She felt pleased that he had begun to talk. The Chablis had helped him overcome his shyness. She poured more wine and asked if he would like some coffee.

‘Quiche with white wine, and now coffee! I’m living it up today!’

When she came back from the kitchen with the coffee, she found him stretched out on the sofa in his stocking feet with one arm over his eyes. It was not what she had expected. A trifle eccentric, even irregular, she thought.

‘Coffee up!’ she said, loud enough to rouse him.

He rubbed his eyes and looked all around in a daze. ‘Well, blow me down! It must have been the wine. I never have wine at lunchtime, you see.’

He did not allow the wine to impair his dedication to his job, however. He worked steadily through the afternoon until he had renewed all of the defective wiring. Finally, around 4.30 he asked her to test her phone and computer.

‘Well done!’ she said, noting his delighted smile. ‘What a relief to be back on the air again. I simply felt marooned without my computer and telephone. I really must get myself a smartphone. I’d like to have your name or business card in case anything goes wrong again.’

‘Nick Stout,’ he said.

‘I love monosyllabic names because they sound so strong. Before you go, we’ll enjoy what’s left of the wine while you tell me the complete history of Gregor Samsa and all the potentiometers you have found in it.’

She meant it as a joke because she thought the word ‘potentiometer’ amusing. He was not offended, however. As he sipped the wine, he told her the story of Gregor Samsa from start to finish, and then began telling her a few of the thousand or more interpretations that might be put on it.

‘It’s a most original story,’ she said in order to encourage him further. Melanie was always saying that she should talk to men more often and find out about their fads and fancies. She even suggested that she harboured an unconscious hatred of men, which she knew wasn’t true. ‘Not talking to men is one way of making yourself ill again,’ Melanie had advised. When she replied that she could never think of anything interesting to say to men, Melanie claimed that if you talk to any man about himself, he will listen to you for hours on end.

‘Why do you say the story is original?’ Nick asked.

‘Because thinking up a story about a man turning into a giant beetle takes nothing short of genius.’

‘There are several stories of men turning into wolves, and gods turning into bulls and swans. That is not what makes it so original.’

‘A bull is strong and a swan is beautiful – but a big, ugly beetle! It’s disgusting.’

‘And isn’t that what makes reading it such an unforgettable experience – the horrible obscenity of the subject. Just think of the misery endured by poor Gregor, coping with life in the body of a beetle while his mind remains that of a man. And think of his sufferings as he tries to cope with his enraged father and uncomprehending family, not to mention his impossible boss. His life is hell – hell in himself and hell in his relationships with other people. Hell both inside and out.’

‘How he must have longed to be back in his own familiar skin again! I suppose we all should value our bodies more,’ she smiled. ‘After all, they’re more comfortable to live in than a beetle’s repulsive frame.’

‘That isn’t what the story is about,’ he said with a vehemence that made her take note.

She was enjoying the conversation, telling herself that for once Melanie would be proud of her. ‘What do you think it’s about then?’ she asked.

‘It’s about an ordinary man with an extraordinary handicap, and how he tries to get by in an indifferent and indeed hostile world.’

She did not agree with him but she thought it best not to express dissent just yet. Instead she smiled and asked him what he himself would like to turn into, thinking that he would say a billionaire.

‘I’m saving up to become a doctor. I’m a medical student, you see. In my holidays I work as a telephone engineer to get enough pocket money together for the next term.’

‘I admire determined men. Dedication is the surest way to success. Just imagine all the good a truly dedicated doctor can do. My father was a surgeon, so absorbed in his work that his patients and students saw more of him than I did. When you qualify, try to lead a balanced life. Balance is the secret – no matter what you’re doing.’

‘Balance!’ he raised his head and looked at her as if he had never really looked at her before.

‘You’ve given me a fresh insight into the life of our friend!’ he said enthusiastically. ‘I do believe that between us we’ve hit on something. I’ll read the story again in the light of your idea.’

‘I’ve just had another idea,’ she said almost conspiratorially. ‘If you’re not planning to go out this evening, I’ll prepare a simple meal for us both and we’ll talk more about the effect that living in a beetle’s body must have had on poor Gregor’s mind. With your interest in medicine, you must have a view on the subject.’

‘After a day’s work I look forward to going back to my flat, stretching out on my old horsehair sofa, and listening to music – mainly Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Stravinsky. All four had an impeccable sense of balance.’

‘If you stay to dinner, you could listen to some Scarlatti sonatas with me. You can tell me about Stravinsky, and I’ll let you in on the secret of enjoying Scarlatti as interpreted by Vladimir Horowitz.’

‘It’s very kind of you but I simply couldn’t sit down to dinner without at least having had a shower after my day’s work.’

‘Nothing is impossible in this most impossible of worlds,’ she assured him. ‘Let me show you to the bathroom and get you a fresh towel. Sadly, I don’t rise to a razor. As you may have noticed, I have no need of such male accoutrements.’

While he showered, she prepared a chicken salad with avocado, cucumber, grated carrot and radishes. She felt quite pleased with herself and with how the day had gone. Here she was doing something Melanie had never done: giving dinner to a doctor in the making, perhaps even a dedicated humanitarian with a life of good works ahead of him.

He entered the living room refreshed and smiling. He now looked quite handsome in spite of his stubble. He was no longer tongue-tied. Over dinner he asked her what she did for a living, and she told him that she was a freelance researcher.

‘I work on projects for authors, journalists, professors, publishers, in fact anyone who needs a dogsbody to ferret out facts in libraries or wherever they are to be found.’

‘You must be a treasure-house of abstruse information!’

She could see from his look that he was impressed. ‘I enjoy the ferreting, but I spend far too much time here on my computer trawling the internet for leads – you know the drill. Ideally, I’d like a job where I could be with other people without being seen by them.’

‘How come?’

‘No matter where I go, I feel that people don’t see me as one of themselves. They treat me differently and say things to me that they’d never say to each other. It began at boarding school. The other girls didn’t like my bleached hair and whiter-than-white skin. First they called me Albino O’Leary, then AOL, and finally Whitewash. Life at a girls’ school can be very cruel.’

‘But your hair is lovely, so fine to look at. They were obviously jealous of your smooth good looks and so transparent skin.’

‘I was different. That’s the nub of it. I was another Gregor Samsa. Now you know why I am so taken with his story. I really must read it because it’s the story of my life so far.’

‘Please have my copy. I’ve read it so many times that I know it by heart.’

‘I wouldn’t dream of accepting your copy of such a precious book.’

‘I have it in seventeen different editions, including a limited edition of five hundred copies. My copy is numbered 432. If you add those numerals together, they come to nine, a mystical number, you see. For me it’s a kind of bible, a book of life that has often rescued me from despair.’

‘We’ve only just met but I feel I know you better than anyone I’ve ever spoken to.’

‘And I feel I know you as well as I knew my little sister Emily, who died when she was ten. She was very dear to me. I think of her every day.’

‘It’s so nice to be compared to a favourite sister. I envy women who have a brother to be close to. I’m an only child, you see.’

‘I know the feeling. When I lost my little sister, I felt I’d lost a world. My father and mother stopped talking to each other. No one laughed or made fun anymore. I grew up in a house of silence which at times made a screaming noise inside my head. At school I found it difficult to talk to the other boys and girls. I had become another Gregor Samsa long before I knew his name. It’s strange how a story written before I was born could foreshadow my life with such daemonic accuracy.’

‘The world is full of Gregor Samsas, I suspect.’ She gave him a sympathetic smile.

He looked as if taken aback, perhaps even angry, as if she’d said something quite outrageous. For a moment she felt afraid.

‘Gregor Samsa was a very special person,’ he declared, ‘and only very special people can claim to know what he came through. We mustn’t exaggerate the extent of our sufferings but neither must we make light of them. Like Samsa’s, they are unique. There is no Samsa Society, and never will be … Oh, I do think I’ve talked too much. If you don’t mind, I’ll have a little snooze on your sofa before I leave. It’s been a lovely evening for me, a visit to fairyland and a world of childhood simplicity that I didn’t know still existed on this ravaged planet.’

‘You look tired. You’d better lie down for a while,’ she advised. ‘I’ll wash up and wake you at eleven.’

She, too, had enjoyed the evening, so different from anything she’d ever experienced. She had proved to herself once and for all that a man could take her ideas seriously. She found herself hoping that their paths might cross again. If not, she would still have something interesting to tell Melanie when she returned from Paris.

He woke up on her bed the following morning. They were both naked and her body felt cold in his arms. He looked for blood but there was none. Next he examined her face and arms for signs of violence. He turned her over on the bed. There were no telltale marks on her back or buttocks. It simply made no sense. Then he noticed the open drawer and her underwear strewn all over the floor. The silk scarf was still around her neck. Beneath it were the marks he had hoped never to see again.

The last thing he could recall was her promise to wake him up at eleven. In death she reminded him of Emily when she was only ten and he fourteen. She, too, had a silk scarf round her neck but he had no recollection of how she had died. His father whispered the word ‘blackout’ to his mother. They told the family doctor who nodded and put it down as a childhood accident.

This was different. It was 8.30 on a Saturday morning in April. He was now twenty-two, and his real life had not yet begun, as she had reminded him twice over dinner. The company van was still parked in the road outside for all to see. She had a perfect body, and she was such a lovely person, just like Emily. It was his personal tragedy, falling in love with girls he should never have loved. He would never again meet anyone like her.

What on earth was he to do?

Ruth Dudley Edwards

Ruth Dudley Edwards is an historian and journalist. The targets of her satirical crime novels include the civil service, Cambridge University, gentlemen’s clubs, the House of Lords, the Anglo-Irish peace process, the Church of England and literary prizes. She won the 2010 Crime Writers’ Association Non-fiction Gold Dagger forAftermath: The Omagh Bombings and the Families’ Pursuit of Justice, the 2008 CrimeFest Last Laugh Award forMurdering Americans– set in an Indiana university – and the 2013 Goldsboro Last Laugh Award for her twelfth novel,Killing the Emperors, a black comedy about the preposterous world of conceptual art. www.ruthdudleyedwards.com

It’s Good For You

‘That Deirdre Plunkett must’ve been a saintly woman,’ said Detective Inspector Jeffrey King. ‘And that’s the thanks she gets for it!’

‘It could have been an accident, Jeff. Couldn’t it?’

‘You’re too soft, Mandy. I’ve seen people who’ve fallen down stairs and people who’ve been pushed and I’m telling you Miss Plunkett was shoved by that woman she was caring for. Why else would the two of them have fallen?’

‘Maybe Miss Plunkett was helping Kate Kenna down the stairs and one of them tripped and brought the other one down. You know, like mountain climbers on a rope.’

‘Maybe, but I doubt it. It doesn’t fit with the way they were lying or that mark on Plunkett’s face. I’ll bet that loony did for her in a fit of temper. Only consolation is it did for her too.’ King took another slug of coffee, banged the mug back on the coaster that said ‘Save Water Drink Beer’, and shook his head with despair at the frightfulness of the human race. ‘Murderous bitch.’ He embarked on one of those rants about modern society that Sergeant Mandy Cox was well used to. Absentmindedly nodding as words like ‘entitlement’ and ‘ingratitude’ floated by, she focused her mind on the scene in Acorn Cottage. The two women sprawled together in death on the stone slab at the bottom of the wooden staircase had been a striking contrast. Underneath, facing upwards, plump, pink-cheeked, enveloped in a scarlet kaftan and with her hair dyed orange, was the house-owner, Deirdre Plunkett. On top, facing down, was scrawny, mousey Kate Kenna, wearing a dirty pale pink polyester nightdress.

Mandy was still more squeamish about corpses than she could afford to let on, and so had been relieved that these two weren’t long dead. Had the postman not seen them through the hall window when he rapped on it to get Deirdre Plunkett’s attention, who knew how long they might have lain there.

‘However, I’d better shut up and you’d better get a move on,’ said King, one of whose saving graces was that venting his ire restored him to relative equanimity. ‘We’ll need more info about these women for the inquest. And since I’ll lay you a tenner at 5-to-1 that the PM finds some evidence that Kenna pushed Plunkett, we’d better look for a motive other than her being mental or the human rights brigade will be after us.’

‘The postman didn’t seem very clear what he meant by “mental”, Jeff.’

King yawned vigorously. ‘We know sod all. I’ve got to get back to work on those stabbings, so you bugger off and get busy. And come and tell me about it when you’ve got something.’

‘That’s terrible,’ said the ward sister. ‘I remember Kate Kenna very well. Nice woman. Very gentle and undemanding.’

‘But with mental problems?’

‘No. She’d been a bit low, but so would anyone have been. Her parents had been killed in the car crash in which she broke her legs and pelvis, an operation went a bit wrong, she was in traction on and off and she got a nasty infection. So she was here for several months. Anyone would be depressed.’

‘That’s odd. The postman spoke of her as “mental”.’

‘Did he know her?’

‘No. He said he’d never met her but that he’d once seen her waving at him from an upper window and Ms Plunkett told him she was recovering from a nervous breakdown. He thought Plunkett was a saint to be looking after her.’

Sister Coulson had another look at the file. ‘This is a bit odd. When Kate was discharged four months ago she was thought to be well on the road to a full recovery. Her legs and pelvis had healed and she was beginning to walk normally again, the infection had cleared up, and though she was still grieving, she seemed anxious to start a new life. It says here she was offered antidepressants, but she said she was fine and turned them down.’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t get it, officer. And I don’t get why she stayed so long with Ms Plunkett. She definitely said she was going travelling soon in France.’

‘Did you know Deirdre Plunkett?’

‘Just a bit. She was a patient here for a few days after she had a nasty break to her arm. That’s how she met Kate and afterwards she used to visit regularly.’

‘Did you talk to her much?’

‘Sometimes she’d stop by to say hello, and, of course, Kate sometimes talked about her. They were both Irish so they could chat about places they knew and so on. She seemed to be a lovely person, full of life and energy and with a big personality and you couldn’t but be struck by how much she wanted to help people less fortunate than herself. Kate said she talked about all the suffering in the world and how only little acts of kindness could improve things. And she was a great one for those. She’d bring little treats for Kate and chocolates for us. “They’re good for you,” she’d say laughingly when we said she shouldn’t. And she insisted that when Kate left she should stay with her for a few days of normality and a bit of cosseting after being cooped up so long in hospital.’

‘A few days?’

‘Yes, that’s definitely what Kate said.’ Sister Coulson shrugged again. ‘Maybe they got on so well they decided she’d stay for much longer.’

‘Or maybe she had some kind of relapse soon after she went there and Ms Plunkett was looking after her.’

‘But you’d expect her to come back to the hospital, and there’s nothing about that on the file.’

‘Maybe she went to Ms Plunkett’s doctor.’

‘Maybe. I don’t think I can help any further, officer. Here are the contact details and copies of the medical records and if I find anyone who might be able to tell you more about either of the ladies, I’ll let you know. But I think it’s unlikely.’

‘It’s plain as a bloody pikestaff, Mandy. The postman was right. She must have been mental to launch herself like that at poor Miss Plunkett and kill the two of them. The pathologist was clear that Kenna head-butted her. The coroner shouldn’t have any difficulty in coming up with a verdict of murder and suicide. After all, wasn’t there a padlock on Kenna’s door, presumably for when she was violent?’

‘I just don’t think it’s that simple.’

‘Oh really! So what was going on? S&M wrestling at the top of the stairs that went wrong? These days, you never know.’

Mandy smiled indulgently. ‘No. They didn’t look the types. But I don’t think we can be certain that Kenna was mad and Plunkett was an unlucky victim. There are a few inconvenient facts. First, why didn’t Plunkett mention Kenna’s condition to her doctor? What right did she have to lock her in? Why was Kenna so much less healthy than when she left hospital? The pathologist mentioned malnutrition. And why was she dirty?’

‘Here’s a question for you. Why do you have to complicate everything? Can’t we just leave it as it is?’

‘If you really believed that, Jeff, you’d have pushed the interpretation that it was a double accident instead of wanting to nail it on Kate Kenna. It’s from you I’ve learned the satisfaction of trying to find out what really happened rather than what’s convenient to believe.’

‘Flattery never fails with me, does it?’ King sighed. ‘You can have a couple of days and PC Jones to dig around and then I’ll haul you back to something useful.’

Mandy loved working with Joe Jones, a solid, unambitious, conscientious constable who lived for his family, his church and his improbable fan-ship of Deanna Durbin, a wholesome film star who had blossomed in the 1930s and 1940s and then faded into obscurity as a good wife and mother. She had, Joe explained, the rare combination of talent, beauty and goodness. When lumbered with yet another investigation into greed or violence or degradation or just plain wickedness, he found it a great release to go home and watch her singing on YouTube, or to chat on Facebook to some of the faithful about the finer points of one of her movies about the triumph of innocence.

‘You know what I want, Joe.’

‘Everything I can find out about the two of them on the net and the phone.’

‘That’s about it. When I’ve harassed the IT crowd about getting into Plunkett’s computer, I’m off to check out the house and the neighbours.’

The only neighbours, several hundred yards away from Acorn Cottage, knew nothing about Deirdre Plunkett except that she was big, wore bright clothes and had lived there for years. She would wave at them if she passed them in her little car, but from the beginning she’d turned down all friendly overtures by making it clear she liked to keep herself to herself. Seemed a bit odd, they said, that anyone would want to live such a solitary life, but there was no accounting for tastes. Extracting from them an address and number for the couple they’d bought the house from, she walked back to the cottage, which didn’t seem initially to yield much either. Forensics had done their stuff and had cleaned up after themselves.

Apart from the room at the top of the fatal stairs, it was clean and rather characterless. The store cupboard and the wide range of cookery books in the kitchen indicated Deirdre Plunkett had been a keen cook, the sitting room suggested she enjoyed intricate embroidery and watching nature films, she was keen on books of quotations and her wardrobe had a lot of loose, bright clothes. All of which made the room that was presumably Kate Kenna’s a strange contrast.

There were a few books and DVDs – all majoring in violence. If these were her choices, this woman was big on horror, particularly Clive Barker and Stephen King: as a viewer, she opted for the likes of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Reservoir Dogs and Django Unchained. Mandy looked disbelievingly at Crash. Wasn’t it beyond weird for a woman who’d been in a fatal accident to want to watch a film about people with a sexual fetish for car crashes?

And how could Deirdre have put up with such a filthy visitor? Everywhere was dusty, and her bedclothes looked as if they hadn’t been changed for months. The bathroom wasn’t much better except for the bath, which looked unused. A dead insect was lying near the plughole, and Mandy turned on the cold tap to wash away the corpse, but nothing happened. There was no hot water either. The sink provided cold but not hot water.

You could hardly blame Kate for being dirty if there wasn’t any water, thought Mandy, texting Joe Jones to find out if local plumbers had done or been asked to do any work at Acorn Cottage recently. Didn’t seem to be any bathroom cleaner either, or even soap, and the only towel was very small. She looked in the closet for clothes and found none. The drawers were empty too, and there were no suitcases and no handbag.

Maybe Kate had lost all her belongings in the crash, thought Mandy, but she wouldn’t have left hospital wearing only a nightdress. She went around the house looking for her possessions, and found nothing. A search in the tidy garage was similarly unsuccessful. She sat down in the little conservatory and tried to make sense of this, until interrupted by a cat that came through the door flap and seemed to expect her to be overjoyed by his antics with a tormented baby bird. When she reluctantly wrung the fledging’s neck and dropped the tiny corpse in the bin in the kitchen, the cat was extremely indignant. It slunk off to the end of the small garden in search of more prey, which seemed to be promised by a bird table in a corner of a tiny rose garden overlooked by a tree which the cat scaled rapidly. As he crouched on a branch looking expectant, she went uneasily back into the house and looked vainly for cat food to distract him. She was out the door like a rocket a few minutes later, shouting as the cat approached bearing a new squeaking burden, an adult sparrow which proved already too injured to save. This time she placed the dead bird under one of the rose trees, which were arranged in a row, which looked odd because they were at very different stages of growth. It’s the cat I should be strangling, she thought: he’s going to work his way through the entire family by the weekend at the rate he’s going.

Leaving the scene of his crime, she went back into the house and made phone calls.

‘I’ve talked to the previous neighbour, Joe. He met Deirdre Plunkett about fifteen years ago when she became companion/carer to Acorn Cottage’s Maggie Hayward. He said that when Maggie became ill she became reclusive, as was Deirdre after Maggie died, leaving the cottage to her.’

‘What did she die of?’

‘He thought pneumonia.’

‘Do you want the death certificate? And anything the doctor might remember?’

‘Yep. And the will. And anything useful from the solicitor.’

‘Of course. Now here’s what I’ve got that’s interesting …’

She brought Joe Jones with her to back her up when she’d made her case to DI King, who took copious notes and didn’t interrupt. ‘OK,’ he said, when she’d finished. ‘You’ve concocted a pretty tale, but there’s no proof.’

As she opened her mouth to object, he went into familiar demolition mode, banging right-hand index finger against left as he numbered his points. ‘One! The doctor didn’t think Margaret Hayward’s death suspicious.’

‘But why hadn’t Plunkett called him in?’

‘Because pneumonia doesn’t always show. Two! It’s perfectly natural that Hayward would have left the house to Plunkett. She didn’t have close relatives.’

‘But she did change her will, sir,’ said Jones.

‘Yes, but why shouldn’t she have? She wasn’t robbing any relatives. You tell me she’d left her money to the Distressed Gentlefolk’s Aid Association, for God’s sake. Seems perfectly reasonable that instead of leaving it to toffs, she’d be glad to leave it to someone who’d looked after her.’

‘But the solicitor did admit to slight unease that he never saw Mrs Hayward alone to discuss her change of mind.’

‘Slight unease butters no parsnips, Joe. Three! You’ve discovered that Plunkett felt done down when her grand-aunt left her nothing in her will. Happens all the time. Doesn’t turn people into murderers.’

‘She’d looked after her in a lonely farm in the west of Ireland for five years,’ said Mandy. ‘And then she leaves everything to the son in America who hardly ever came home to see her. It could sour anyone.’

‘That’s the sort of thing Irish peasants do, isn’t it? Favouring sons and that and everyone making a big deal of it. I saw some movie where they were all killing each other over some grotty old field. One of my wife’s Irish cousin’s been conducting a feud over a will for the last twenty years.’

‘Exactly. Plunkett had been promised a substantial legacy, and she got nothing, sir.’

King spotted that his contribution had not helped his rebuttal. ‘That’s just the story the gossipy old neighbour told you, Joe.’

‘Isn’t what’s relevant is that it’s what Deirdre told the gossipy neighbour?’ asked Mandy.

‘No, because either of them could be making it up. Now let’s get on with it. Four! Joe’s found a couple of old biddies that everyone’s lost track of that are supposed to have been friendly with Plunkett when they met at church. So what? They’re still drawing their pensions.’

‘But are long gone from the addresses their banks have for them.’

‘So they’ve moved and didn’t mention it. Old ladies vanish. Happens all the time. Five! Mandy thinks Plunkett wasn’t looking after Kenna properly. And the plumber she used says he hadn’t been called to fix her bathroom. Bloody hell! She was inefficient. And as for those possessions, maybe she’d got rid of them until Kenna was better and they could get some more. Maybe she thought they were infected. Old people get funny ideas. What have I forgotten?’

‘Kenna’s money, sir?’

King knew Mandy was rebuking him when she called him ‘sir’. He suddenly grinned in the disarming manner he employed when he most needed it. ‘I grant you that, Mandy. Haven’t come up with a way of explaining it away. I don’t know why so much was being steadily drawn out on her debit card and where it went and I grant you it looks suspicious. You two can have another twenty-four hours to come up with something.’

He looked sternly at her. ‘But you can forget that stuff about what might be in the rose garden. We’re cops. Not fiction writers.’

Mandy had another go at the IT people, and was promised a result later in the day. She left the money-chasing to Joe and, bearing a tin of cat food, returned to Acorn Cottage to look for inspiration. There was no sign of the cat, so maybe he was an impertinent stray and the cat flap was from earlier days.

Having been back to Sister Coulson to ask more about Kate, she had been grimly unsurprised at being told she was a) fastidious and b) mostly read Victorian novels.

Unhappily, she went up the stairs to where Kate had spent her last days, surrendered to her imagination and pretended she was imprisoned. She considered escaping through the window, but it was double-glazed and appeared to have been glued shut. Besides, the drop was sheer and even at her age and with her relative fitness, she doubted if she could have reached the ground alive. She searched the bed to see if by any chance some of Kate’s treasures were hidden there. All she found was a biro under the dirty pillow.

But there was no paper.

It took her only a couple of minutes to race through the books flicking through the pages until she found one with writing on the inside of the covers and wherever else there was space. Kate Kenna had – if not a black sense of humour – an instinct for the apposite. She had left her testimony in Stephen King’s Misery, a book about someone being tortured to death by a woman who had claimed to be his saviour.

‘I’m in a nightmare and can see only one way of getting out of it, which will probably prove fatal to me. I’ve been imprisoned for several months by someone who is trying to drive me mad or kill me, or both. Does anyone realise I’m missing? If they do, they won’t have the faintest idea where I am. Having no access to a phone or the internet, I haven’t been able to communicate with the outside world. I stare out the window in the hope of seeing someone pass by, but no one does except for the postman and he never looks up since the time I waved at him.

‘What happened to me? Well, I was very vulnerable and Deirdre was very charming. Solicitous, sympathetic and interested. She asked me for my story, wanted to hear everything, listened intently and asked good questions. I was desperately lonely and opened up to her. I told her about my marriage in America, about the hopeless attempts to conceive, the divorce and about how I could no longer face teaching. I told her I’d always been close to my parents and would ring them every week, but had no other family except my sister whom we hadn’t seen since she joined the enclosed convent. About how I’d gone back home to County Clare to lick my wounds and work on the farm and about how at that time I hadn’t been ready to socialise. And how my parents and I decided to make a new start and sell the farm. And about how, after getting a good price, after their lifetime of drudgery and mine of disappointments, we were intent on enjoying ourselves for a change and were on our way to France to find a little house to rent somewhere warm before deciding where we wanted to settle. She kept saying what a good idea that had been and that at least when they died my parents were happy.’

Mandy’s phone announced a text message from Jones. ‘Blimey! Wait till you see what’s on her computer!’

‘Back to you in ten,’ she replied.

‘It was nice that she was Irish, and had been to my part of the country and that we could talk a bit about the scenery. And she seemed to know a bit about some writers I mentioned. I now realise that if I said a name, she went home and looked it up, which is why she’d later produce germane quotes from Jane Austen or Dickens or Yeats. In fact, she’d quote bits of poetry to me that were sometimes comforting and inspirational. She found out what kind of books I liked and gave me the odd one.

‘I’d been in such a half-life for a long time, I was only just coming back to some kind of normality. I would ask her about herself, but didn’t realise until later how sparing she’d been with information. There had been a period caring for a beloved cousin who’d left her some money, she had a modest pension from her job working for a world peace charity, a peaceful little cottage in the country and a rescue cat. She had a gift for play, and we had silly games about pet hates and our Room 101 terrors. Talking like that was good for me, she said. It was her favourite phrase and it seemed very positive at the time. All I can remember is that she hated beer, marmalade and beige. As I later discovered, she noted my admitted hates and fears and put them to good effect: pale pink, polyester, parsnips, lumpy porridge, liver, snails, oysters, organs, Creme Eggs, graphic violence, horror and ghost stories. Anything I didn’t like, Deirdre had conscientiously stocked up on. Dirt came naturally.