11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

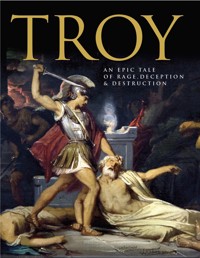

“Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships/ And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?” – Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus A story of gods and mortals, of such famous episodes as the Trojan Horse and Achilles mortally wounded in his heel, of warriors such as Odysseus and Hector, of beauties such as Helen, of leaders such as Agamemnon and Menelaus, the Trojan War is a classic story from the ancient world that never ceases to lose its appeal. But how well do we really know it? Do we remember Odysseus feigning madness to avoid the battle? Or Achilles, that great warrior, disguising himself as a woman so that he didn’t have to fight? Troy – An Epic Tale of Rage, Deception & Destruction tells the story of the Trojan War from its beginnings with the sparring of the gods to the love story between Paris and Helen to the war fleet, the siege, and on to the final battles and destruction of the city. From a conflict that’s set in motion by Helen – ‘the face that launched a thousand ships’ – it ends, ten years later, with Odysseus setting sail on what turns out to be his own ten- year voyage home. The book offers a fascinating history that provides a broader context for the war, examining the social and political background, the role of women in Greek society, and the weapons and style of warfare practiced. It also highlights where sources differ on aspects of the story. Illustrated with more than 180 colour and black-and-white artworks, photographs and maps, the book is an expertly written account and investigation of one of the classic stories of ancient mythology.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 275

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

TROY

TROY

AN EPIC TALEOF RAGE, DECEPTIONAND DESTRUCTION

BEN HUBBARD

This digital edition published in 2024

Copyright © 2018 Amber Books Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright holder.

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

United House

North Road

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

X (Twitter): @amberbooks

ISBN: 978-1-83886-621-1

Project Editor: Michael Spilling

Designer: Jerry Williams

Picture Research: Terry Forshaw

Contents

Introduction

1. The City of Troy

2. The Warrior Kings

3. The Role of Women

4. The Savagery of the Siege

5. The Death of Patroclus

6. Gods, Men and Homer

7. New Civilizations from Old

Map of Bronze Age Greece

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

Troy is perhaps the most famous city in history, the poem about the Trojan war perhaps the greatest ever written. It is how the world remembers the ten-year Greek siege and the saga of ‘strife, havoc and violent death’ that raged before Troy’s walls.

The fall of Troy is depicted here on the fifteenth century bronze doors of Castel Nuovo, Naples.

THE DOWNFALL of Troy is not described by Homer, author of the Iliad, the epic poem about the war, but the Roman poet Virgil. It is the Trojan prince Aeneas, hero of Virgil’s Aeneid, who details the terrible slaughter of his people. Aeneas tells about the deception of the wooden horse and how the Greeks put Troy to fire and the sword. No-one found was spared, not the young, female, nor old:

Pyrrhus came on, like Achilles himself in his onset. No bolts or bars, no guards could hold off that attack. The door crumbled under the ceaseless battering. The hinge-posts were wrenched off their sockets, and fell outwards. Utmost violence opened a passage. With access forced, and the first guards cut down, the Greek army flooded in and filled all the palace with its men; more fiercely even, than some foaming river which breaks its banks and leaps over them in a swirling torrent and defeats every barrier. –VIRGIL,AENEID, BOOK II

A rendering of Troy being sacked by the Mycenaeans is shown in this seventeenth century painting by Jean Maublanc.

The legendary city of Troy, a once great trading centre of splendour and sophistication, was destroyed by war some time in the thirteenth century BCE. For centuries afterwards, the ruined stone and rubble of this city lay buried with the secret of its fate. There has seldom been a more complicated archaeological pile than the mound known as Hisarlik in Turkey. Here, where experts agree Homer’s Troy lies, are buried not one but nine different cities. The hill contains skeletons, heaps of sling missiles and evidence of fire and violent destruction. Troy was a city that tried to defend itself, but was in the end overrun. Does this mean the stories of Homer and Virgil were true?

The archaeologists set out to prove they were; that a coalition of Greeks had sailed to the city to take back Helen, estranged wife of Menelaus of Sparta. But Troy’s walls could not be breached and the Greeks besieged the city for ten years before winning it by trickery. Helen, slaves, plunder and vengeance were the prizes.

The first man to dig for the truth was nineteenth century millionaire, Heinrich Schliemann. Schliemann was a fantasist who falsified evidence to fit the myth of Troy. His approach at the dig site was brutal. In his rush to discover the city, Schliemann cut a deep swathe through the centre of Hisarlik, destroying large chunks of evidence in the process. The amateur archeologist partly redeemed himself, however, when he unearthed the tombs of the warrior kings who ruled at Mycenae.

Glory and Treasure

The warriors of the Iliad belonged to a great age of heroes, when the superpowers of the Bronze Age were led by battle-hungry aristocrats bent on glory and treasure. Homer describes the complications of this warrior code: there is pig-headed Agamemnon, king of the Greeks; there is the coward who caused all the trouble, the prince Paris; there are Hector and Achilles, the supreme warriors doomed to die.

No one is a match for Achilles in war, but his rage and his self-centredness cost the lives of ‘countless’ numbers of his comrades. Achilles refuses to continue fighting when his leader Agamemnon takes from him Briseis, a female slave won in battle. He sulks in his tent while the Greeks are slaughtered. The use of women as commodities is one of the central motifs of Troy; the capture of female slaves as booty the reality of Bronze Age war.

This bronze Corinthian helmet dates from around 500 BCE.

The great Mycenaean city-states were wholly dependent on a workforce of slaves. The Mycenaean warriors were predatory raiders who attacked Aegean settlements and took captives as forced labour. Much treasure was needed to support the lifestyles of the palace nobles; being a ‘sacker of cities’ was a title of honour among them. Tablets found at the palace of Pylos list hundreds of women snatched from Anatolian shores. Some have wondered if the Iliad’s Helen was simply a metaphor for the many slave women taken from Troy.

To bribe Achilles back into the siege at Troy, Agamemnon offers Achilles ‘twenty Trojan women, the loveliest after Helen herself.’ The extent of Achilles’ interest in female sex slaves, however, remains in dispute. It is the death in battle of his beloved Patroclus that persuades Achilles to return to the fight. When he hears Patroclus has been slain, Achilles wails inconsolably and throws himself over the corpse. This gesture was usually reserved for the wives of fallen husbands, and many Greeks believed that Achilles and Patroclus were not only brothers-in-arms, but also lovers.

Love Between Men

Ancient Greece had a long tradition of acceptance and even celebration of male homosexuality. Some city-states practised an elaborate code of pederasty, or sexual relationships between a man and a boy. The Theban Sacred Band was a formidable fighting elite made solely of homosexual couples; the Greek historian Plutarch was a great advocate of this model’s effectiveness in war.

The Theban Sacred Band was a formidable fighting elite made up solely of homosexual couples.

In a blind rage, Achilles sets out to avenge the death of Patroclus, a period of wanton slaughter that ends with the slaying of the Trojan prince, Hector. Achilles cuts holes in Hector’s ankles so he can drag his body around the walls of Troy by chariot. Such is the characteristic brutality of the Iliad. Homer is a virtuoso of literary violence. His warriors are graphically maimed and slain, their skulls split and their eyeballs popped, their teeth shattered by spears and their severed heads rolling in the dust while ‘yet speaking’. However, alongside the brutality is pathos, as Homer gives each fallen warrior a name and a biography. The terrible human cost of war is never forgotten.

In the historical world, however, those who fell in the great Bronze Age collapse remain largely faceless and nameless. At this time, the great city-states of the Mediterranean and the Near East were attacked by earthquakes, famine and barbarians. As a dark age descended, the symbols of civilization were lost: trade, diplomacy and literacy. When the Greeks re-emerged from the dark they had to reinvent themselves and their alphabet. A great Greek poet probably used it to create the Iliad. And with it, the story of Troy became part of history.

THE CHARACTERS OF TROY

THE CHARACTERS OF the Iliad, the Odyssey and the Aeneid are central to this book. A short biography of each follows:

THE GREEKS

Achilles

Born of the goddess Thetis, Achilles is the greatest Greek warrior. He slays the Trojan champion Hector, after sulking for much of the war.

Agamemnon

King of Mycenae and leader of the Greeks, his clash of egos with Achilles nearly costs him the war.

Helen

Princess of Sparta and daughter of Zeus, Helen is the most beautiful woman in the world, and her abduction leads to the war.

Patroclus

Achilles’ closest comrade in arms and presumed lover, Patroclus’ death sparks Achilles’ return to war.

Menelaus

Helen’s husband and Agamemnon’s brother; it is partly to save Menelaus’ honour that the war in Troy is launched.

Odysseus

King of Ithaca and architect of the wooden horse, he is the hero of the Odyssey, the sequel to the Iliad and the tale of Odysseus’s journey home after the fall of Troy.

THE TROJANS

Hector

Second in war only to Achilles, Hector is the son of Priam, king of Troy.

Priam

The great leader of the fabled city, Priam is doomed to die because of his son Paris’s folly.

Paris

Vain and cowardly, Paris is a womanizer who prefers the bedroom to the battlefield.

Aeneas

Warrior and leader of the survivors of Troy, Aeneas will lead them to found the new civilization of Rome.

THE GODS

Zeus

King of the Gods, who sides with the Trojans and then the Greeks, after striking a deal with his wife, Hera.

Hera

The wife of Zeus and hater of the Trojans after Paris declares Aphrodite, and not her, winner of a beauty contest.

Apollo

Son of Zeus and champion of the Trojans, Apollo brings a plague upon the Greeks for disrespecting his priest, Chryses.

Athena

Champion of the Greeks, Athena helps break the truce between the two armies by appearing as a mortal and injuring Menelaus so the fighting will resume.

Aphrodite

Goddess of love and champion of the Trojans, Aphrodite offers Helen to Paris.

CHAPTER 1The City of Troy

Troy has haunted the world’s imagination for 3000 years. There is no more famous tale than that of Achilles and Agamemnon, the Trojan Horse, the great city itself and Helen, ‘the face that launched a thousand ships/And burnt the topless towers of Ilium’.

The ancient ruins of Troy, excavated from the mound of Hisarlik in modern-day Turkey.

TROY, or Ilium as Christopher Marlowe calls it above, is portrayed by Homer as a city of great splendour and sophistication. Protected by huge limestone walls and towers, Troy sits high on its rocky prominence like a mounted jewel, a coastal beacon that flashes across the windswept Anatolian plain below and the wine-dark Aegean beyond.

It is to the city that Helen is brought – either willingly as the seduced woman, or by force – by Paris, son of King Priam of Troy. This insult to the honour of Helen’s husband, King Menelaus, sparks the massive Greek expedition to the shores of Troy. Here, as the siege unfolds over ten years, the coalition boils and seethes and threatens to tear itself to pieces; the Greek heroes snarl at one another and snap over the spoils, from this war and others past.

For many of the warriors, loot is the main payoff in a conflict whose purpose is often in dispute. Over time, the lives of the common soldiers encamped in their makeshift beachfront huts becomes squalid. During the day, they are caught in a stalemate of attack and retreat on the battlefield plain before them. At night, they return to rest on beds made of animal skins as wild dogs feed on the carcasses of the fallen. Here, the still battlefield becomes a dark wasteland of ‘corpses, abandoned weapons and black blood.’ Standing behind the Greek soldiers are their ships, ready to transport them back to home and family; except the sails and timbers have long since rotted.

Internal Divisions

While the Greek soldiers remain largely loyal and faceless, their storied leaders are murderously divided. At the start of the Iliad, the supreme Greek leader, King Agamemnon of Mycenae, has a violent argument with the greatest Greek warrior, Achilles, over a woman taken as a trophy of war by Achilles.

This artist’s rendering of the city of Troy during the Bronze Age suggests an all-out assualt on the city’s high walls would have been an unrealistic strategy.

The argument between the two heroes quickly becomes brutal, personal and undignified. Achilles accuses Agamemnon of greed and cowardice. He calls him a drunkard ‘with the eyes of a dog, steeped in insolence and lust of gain.’ The great king, he says, is more interested in loot than in fighting – a deadly insult according to the terms of the warrior code.

This mosaic discovered at the Roman city of Pompeii depicts Achilles and Agamemnon from the Iliad.

Agamemnon in turn accuses Achilles of arrogance and sedition and invites him to return to Greece. ‘There is no king here so hateful to me as you are, for you are ever quarrelsome and ill-affected…go home, then, with your ships and comrades.’

As the anger and uncertainty mounts, their supposed prize, Helen, sits protected in the high citadel of Troy. Here, she weaves a crimson blanket that tells the tale being played out in her honour. The splendid city is set in brutal contrast with the undignified scrap among the Greek soldiers in their makeshift camp. Troy is calm, stable and concerns itself with family life, even during warfare. Inside there is luxury, comfort and resources enough, even after ten years, to make sacrifices of twelve heifers to the gods; outside, the city’s high walls show no signs of buckling before the invaders. The scene is described in the Iliad:

An artwork showing the famous walls of Troy from the north. According to legend, only trickery could bring about the city’s fall.

The splendid palace of King Priam, adorned with colonnades of hewn stone. In it there were fifty bedchambers – all of hewn stone – built near one another, where the sons of Priam slept, each with his wedded wife. Opposite these, on the other side of the courtyard, there were twelve upper rooms also of hewn stone for Priam’s daughters, built near one another, where his sons-in-law slept with their wives. – HOMER,ILIAD, BOOK VI

So Homer paints the picture of the two opposing forces during the action of the Iliad. Here are some of the main players in the drama: Achilles, Agamemnon, Priam, Helen and the city of Troy itself. In the end it would take an act of trickery to bring about the city’s downfall. The Trojan Horse, with its secret band of Greek soldiers, is a symbol so powerful that 2800 years after the famous text was written we still use it as a metaphor in everyday speech. With the horse, the siege is ended and the Greeks destroy the great city with terrible brutality.

THE TROJAN HORSE

PRESENTED TO THE TROJANS as an oversized goodbye offering – but in reality hiding a handful of Greek commandos ready to sow murder and ruin after nightfall – the horse is one of the most unlikely aspects of the Trojan War. Menelaus briefly recounts the story in the Odyssey, as it is Odysseus himself who creeps from the horse with his men and opens the gates for the freshly returning Greek ships.

It might seem inconceivable that the Trojans would be so stupid as to accept the gift. As the Odyssey tells us, some inside the walls of Troy also had their suspicions. Helen herself walks around the horse like an enchantress, mimicking the voices of the Greek soldiers’ wives in an apparent attempt to make them give themselves away.

Can the horse be explained? One theory is that it was actually a siege engine, a type of battering ram housed in a horse-shaped structure that brought down the city gates. This would fit with Homer’s picture of the Greeks as underdogs who had to resort to trickery to win the day.

Another suggestion is that the horse was merely a metaphor for an earthquake that weakened the city’s defences enough for the Greeks to enter. After all, goes the theory, in ancient Greece Poseidon was the god of earthquakes who often took the symbol of a horse. There is also evidence of a devastating earthquake at the supposed site of Troy.

Perhaps it is better to remember that Homer was a poet before all else, and that his poem is a work of imagination. His story might include ancient memories of siege engines and earthquakes along with the knowledge of human treachery. The horse is then both a symbol and an evocation of ancient legend.

More prosaically, the Trojan Horse was traditionally made of wood, so it would have rotted long ago. The horse eludes the archaeologists as it continues to tantalize the historians. The horse, therefore, has to remain a mystery for now.

The 675 BCE Mykonos vase is the earliest object depicting the Trojan Horse. Human bones were discovered inside the vase.

The tale of Troy has the grandeur and apparent inevitability of tragedy. The circle of devastation now complete, Helen travels back to Sparta as Menelaus’ wife; for the Greeks, order is restored; for the Trojans, there is ruin and slaughter.

But the readers of the Iliad, the Aeneid, the Odyssey and the Epic Cycle are left with one overriding question: did any of this really happen?

Searching for Troy

With Troy, a simple question leads to ever harder and more complicated ones. But there are certainly some obvious ones: Was Helen a real person? Would a coalition of Greeks have gone to war over her elopement with a Trojan? Did Troy exist? Where was it? Could it have withstood a siege of ten years? If the war took place, who were its protagonists? Were Achilles, Agamemnon, Priam, Hector and Paris real people? And finally, was the Trojan Horse real and could the Trojans have been naïve enough to bring it within their city gates?

Schliemann was something of a huckster: a scoundrel and self-aggrandizing fantasist who falsified his evidence to fit the myth of Troy.

The answer to most of these questions is: yes, why not? After all, ancient and modern history is full of stranger stories than the legend of the Trojan War. However, there is also nothing conclusive in the evidence for mythical Troy, no clear proof that places Helen, Achilles and the horse at the heart of a decade-long siege. But an examination of the archaeology and history can provide some interesting clues.

The Archaeologists

Archaeologists were often romantics with large imaginations. The early archaeologists who went to excavate Troy were certainly of this sort. Most were hell-bent on proving that Homer’s Iliad was true, to show the world that the bard’s tale was about history. Somehow a poem ‘based on a true story’ seems to have an authenticity lacking in a work of pure fancy.

One of the first and most famous of these early searchers for Homer’s Troy was the nineteenth-century German businessman, Heinrich Schliemann. A self-made millionaire, Schliemann has been called ‘the father of Mycenaean archaeology’, and was once considered among the founding greats of archaeology itself, a science in its infancy when he first travelled to Turkey in 1868. However, despite uncovering much of the site now accepted to be the city of Troy, Schliemann is now also known as something of a huckster: a scoundrel and self-aggrandizing fantasist who falsified his evidence to fit the myth of Troy. Despite Schliemann’s duplicity, he nevertheless made some of the most important discoveries known to archaeology.

Schliemann began his excavation of Hisarlik, a rubble-strewn hillock where archaeologist and colleague Frank Calvert insisted to him that Troy must be buried, in 1870. According to his diaries, Schliemann had stood in a stunned reverie at the site, a copy of the Iliad in hand and seeming to see the Greek army massing on the plain below. Eventually, ‘darkness and violent hunger’ forced Schliemann to retire for the night.

Heinrich Schliemann overlooks his excavation, which ploughed a destructive trench through the centre of Hisarlik.

It had, Schliemann insisted, been his lifelong fantasy to find Homer’s Troy, a fascination that stemmed from a boyhood image of the city given to him by his father. This seems fanciful, as Schliemann – an obsessive compiler of his own documents, which include an 11-volume autobiography, 18 travel diaries, 60,000 letters and nearly 200 volumes of excavation notes – does not mention Troy or the Iliad once before he retired from business aged 45.

Despite his habit of airbrushing his own history, there is no doubt that Schliemann devoted the rest of his life to the pursuit of Troy. He took to the hill of Hisarlik with ferocious gusto and a crew of 200 pickaxe-wielding men. Calvert had explained to Schliemann that there were likely to be many layers on Hisarlik and he would have to dig deep to discover the city supposedly dating from the thirteenth century BCE.

This map drawn by Heinrich Schliemann shows what he believed to be the city of Troy as described by Homer.

Part of the ancient road through Troy. Schliemann took the road as proof of the Iliad’s authenticity, as it was wide enough to accommodate a chariot.

Schliemann’s crew ploughed fast and furiously into Hisarlik, cutting a 14m (46ft) deep trench through the middle of the hill and destroying many precious archaeological treasures in the process. What the crew uncovered within the fifty or so layers of Hisarlik was not one but several cities built on top of the other. Near the bottom, the city later known as Troy II appeared wildly promising. Here were walls and a wide paved road that could accommodate two chariots side by side: it seemed straight out of Homer. More tantalizingly still, Schliemann found evidence of fire scorching the walls, leading him to dub Troy II the ‘Burnt City’. Could this be the remains of the fire the Greeks set in Troy to raze the city to the ground?

International Stir

Schliemann’s find caused a small tremor in the world of archaeology and classical studies. For centuries, Homer’s Troy had been dismissed as a fairy story, a long-distant tale told by a long-dead bard. Now it seemed a real city. Look, boasted the businessman with a sort of proprietorial air, at these ‘great walls’. Beneath the clouds of legend sat a rock of hard fact.

But what proof had Schliemann found? The answer, apart from scorched walls and great mounds of rubble and earth, was very little. The naysayers back in Europe were quick to denounce ‘Homer’s City’ as ‘Homer’s Pigsty’, and even Schliemann himself began to wonder. He needed something concrete, and quickly.

Sophia Schliemann bedecked in the ‘Jewels of Helen’ which, after being photographed, were smuggled out of Turkey in a crate.

Whether out of coincidence or necessity, Schliemann’s moment arrived in 1873. Then he presented to the world one of the greatest discoveries in archaeological history – a cache of precious objects that he called ‘Priam’s treasure’. Schliemann claimed he had found the hoard – gold, bronze and silver weapons and jewellery – with his teenaged wife Sophia one eventful morning. Sophia had gathered many of the smaller items, including rings, bracelets and a diadem, in her apron and carried them back to their house for further inspection. Sophia was famously bedecked and photographed in the jewellery – subsequently dubbed the ‘Jewels of Helen’ – before it was smuggled out of Turkey in a crate to Schliemann’s palatial home in Athens.

The find set the scholarly world ablaze and captured the popular imagination. But the whole business was suspect. For one thing, Sophia had not been on the site at the time of the discovery, but with her family in Athens. It also emerged that the hoard had not been discovered all at once. Instead, evidence pointed to a series of smaller finds over the digging season, which Schliemann had put together as a glittering job lot. The ‘Priam’s treasure’ tag brought priceless publicity, but it was wrong. The treasure was actually found to date from around 2300 BCE: 1000 years too early for Homer’s Troy. Troy II, therefore, could not be the mythical city.

Schliemann had had his doubts privately. Troy II was little more than a citadel 100 metres square (1076 square ft); too small to be the grand city of the Trojan War. The disappointment was intensified by the exhausting task of the dig itself. Malaria, scorpions and biting insects combined with unceasing wind, dust and unrelenting heat often left Schliemann too sick and depressed to oversee the excavation.

There were also problems with the authorities. Schliemann had previously ignored the need for an excavation permit and now the Ottoman government was furious at the theft of its national treasures. A lawsuit ensued. Schliemann would later heal this rift with a sizeable donation. However, he broke his promises to split any findings with the government and not to damage existing structures. This led to great trouble for all archaeologists who followed Schliemann to Hisarlik.

WHERE IS TROY?

THE REMAINS OF THE city believed to be Troy are situated on a northeastern corner of the Mediterranean in what is modern Turkey. Troy would have commanded a strategic point at the southern entrance to the Dardanelles, a narrow strait that links the Black and Aegean Seas via the Sea of Marmara.

Positioned between the Scamander and Simois Rivers (today called Menderes and Dumrek Su), Troy overlooked a large Bronze Age bay that has since silted over and become farmland. This is the Troad, ‘The Land of Troy’. Troy’s location on the trading route between the civilizations of the Mediterranean and those in the east would have made it an important commercial centre as well as a natural stopping-off point for merchants on their voyages through the Dardanelles or the Hellespont, as the strait was known to antiquity.

An aerial view of Hisarlik with the Troad and Dardanelles in the background.

Schliemann claimed that this cache of precious objects, which he dubbed ‘Priam’s treasure’, had been unearthed one evening with his wife Sophia. This turned out to be a lie.

Mycenae

While waiting for the furore to pass, Schliemann turned to the Greek side of Homer’s story. If Troy indeed existed, then so must have the Greeks who attacked it. The natural starting point therefore must be the grand palace of Mycenae, where Menelaus had supposedly pleaded with his brother, King Agamemnon, to help recapture his estranged wife.

Mycenae had been deserted for 2000 years by the time Schliemann reached it in 1874. Located in the Peloponnese on mainland Greece, the citadel of Mycenae commanded a lofty position between the mountains of Hagios Elias and Zara and the plain of Argos stretching out below. To Schliemann, the city seemed as Homer had described, ‘broad-streeted and golden’. The citadel beyond the city’s grand Lion Gate certainly seemed a worthy resting place for Agamemnon, who, according to the story, was famously murdered by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus when he got home from Troy.

For Schliemann to find Agamemnon’s tomb would be to confirm that the ancient king existed and bring the Homeric age of heroes to life. In the late summer of 1876, this is exactly what Schliemann did.

Here, an illustrator offers an interpretation of the Schliemanns discovering Trojan treasures at Hisarlik.

Schliemann was not the first archaeologist to dig at Mycenae, but he was the first to excavate inside the citadel. Within a few metres, he hit paydirt. The first objects to appear were upright stone grave monuments, some of them bearing the carved images of warriors in chariots. But the best was to come: rectangular grave shafts containing the remains of 19 adults and two children, every one of them covered in gold. Fitted over the men’s faces were portrait-type masks beaten from thinly hammered gold; on their chests were gold rosettes and sunburst decorations. The women wore diadems on their heads, and all around the adults lay bronze swords and daggers, their hilts and scabbards depicting scenes of hunting and battle. There was more besides in this splendid hoard: silver and gold goblets and boxes, ivory chests, and hundreds of gold discs decorated with animal motifs.

One of the beaten gold death masks unearthed at the shaft graves at Mycenae.

Schliemann was in no doubt that he was looking at the characters and treasures from the Iliad. There were too many connections for it not to be. Within the scenes hammered out in gold were the boar tusk helmets described by Homer and a depiction of the ‘tower-shield’ as carried by Ajax. There were even the same ‘silver-studded’ swords that Hector gave to Ajax. Vindicated by one of the single greatest discoveries in archaeology, Schliemann described the find in his book Mycenae: ‘For my part, I have always firmly believed in the Trojan War; my full faith in Homer and in the tradition has never been shaken by modern criticism, and to this faith of mine I am indebted for the discovery of Troy and its treasure.’

Except that, once again, Schliemann was wrong. Simply, the graves were from an earlier period, perhaps not even connected with the supposed dynasty of Agamemnon at all. The proof was in the gold itself, found to date from around 1600 BCE, 400 years too early for Homer’s Troy. Once again, the entrepreneur was undone by the complexities of archaeology and the problem of linking myth with fact. The more important truth, however, was that while being dazzled by the riches unearthed at Troy and Mycenae Schliemann had overlooked a far humbler but altogether more significant find that linked the two cities together: fragments of Mycenaean pottery.

Colleagues such as Frank Calvert had insisted to Schliemann that the Mycenaean pottery found at the site at Hisarlik was of great relevance to his search for Troy and should not be dismissed. However, this pottery had been found at Troy VI and VII, both cities at a much higher level than the feverishly uncovered Troy I and II. Now Schliemann realized that much of the valuable material from these upper cities had simply been thrown away. In his haste to find Troy, Schliemann had destroyed much of the evidence in front of him. Convincing himself there was still time to discover his dream, Schliemann organized another dig for 1890. But he collapsed on Christmas Day in Naples and died the following day. The first great archaeologist of the myth of Troy had been utterly defeated by its enduring mystery.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld, assistant and successor to Heinrich Schliemann.

Into the Light

After Schliemann’s death his work continued under his assistant, Wilhelm Dörpfeld. Like Schliemann, Dörpfeld was an incurable romantic obsessed with recovering the mythical city. However, Dörpfeld was a rather more careful archaeologist than his former boss and mentor. Trained as an architect, Dörpfeld sought to develop an overall image of the shape of Troy VI, the city that, according to the Mycenaean pottery found there, was the most likely candidate for Homer’s Troy.

THE NINE CITIES OF TROY

THE SITE OF TROY is made up of nine cities that spanned more than 4000 years of history. A brief description of each is given here:

TROY I: Founded around 3000 BCE, Troy I was a small citadel containing around 20 rectangular mud-brick buildings and surrounded by a 90m (295ft) fortified wall. Its lofty location gave Troy I both a commanding strategic position and access to the sea trade routes through the Dardanelles.

TROY II: Built in around 2500 BCE, Troy II added mud-brick houses alongside its citadel to accommodate its growing population. The citadel was protected by two gates and featured large, rectangular buildings called megarons; these were the religious and political heart of the city. Troy II was probably destroyed by fire.

TROY III–V: After the destruction of Troy II, the settlement went into decline. Little is known about the cities of Troy III, IV and V, except that they became smaller, more fortified and wholly contained within the citadel. After a time of relative isolation, a new city, Troy VI, emerged in around 1900 BCE.

TROY VI–VII: The large Bronze Age cities of Troy VI and VII were protected by great defensive walls, towers and ditches and were home to around 8000 inhabitants. The cities’ economy centred on trade and home-crafts such as spinning and weaving and the manufacture of purple dye from seashells.

TROY VIII: After being abandoned around 1100 BCE, the city re-emerged in 700 BCE as Troy VIII, a Hellenistic city called Ilion. The acropolis, agora and temples were typical of Greek cities during that period.

TROY IX: Sacked by the Romans in 85 BCE, Ilion became a Roman city that was partially rebuilt by the general Sulla. The emperor Augustus later built Ilion into a large city, which survived until around 324 CE. Then Constantinople was founded and Troy fell into its final decline.

A map showing the nine cities of Troy.

By digging around the outskirts of the settlement rather than through its middle, Dörpfeld quickly made a discovery of seemingly greater relevance to the myth of Troy than anything produced by Schliemann: magnificent, towering walls. Buried under 15m (50ft) of soil and rubble, the thick limestone walls were flanked by large watchtowers and stood 8m (26ft) high. These were of a far more sophisticated build than any of the fortifications around Mycenae. There was also compelling evidence that linked the walls with the Iliad