7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

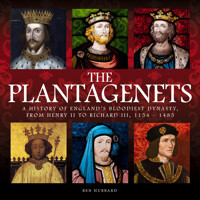

For almost 350 years the Plantagenet family held the English throne – longer than any dynasty in English history – and yet its origins were in Anjou in France, French remained the mother tongue of England’s monarchs for 300 years, and only in its family’s final decades did English rather than French become the language the king used in official correspondence. Furthermore, although the family managed to remain in power for so long, this was not without kings being deposed, ransomed and imprisoned, or without sons plotting against their fathers for the throne and wives turning against their husbands. The Plantagenets is an accessible book that tells the whole narrative of the dynasty, from the coronation of Henry, Count of Anjou, in 1145 to the fall of Yorkist Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. But in charting the fortunes of the family, the book explores not only military victories and defeats across Europe, on crusade and in the British Isles, but how England and its neighbours changed during that time – how the authority of Parliament increased, how laws were reformed, how royal authority could struggle with that of the Roman Catholic Church, how the Black Death affected England, and how universities were founded and cathedrals built. Illustrated with more than 200 colour and black-and-white photographs, maps and artworks, The Plantagenets is an expertly written account of a people who have long captured the popular imagination.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 276

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

THE PLANTAGENETS

A HISTORY OF ENGLAND’S BLOODIEST DYNASTY, FROM HENRY II TO RICHARD III, 1154–1485

BEN HUBBARD

Other related titles include:

Kings and Queens of the Medieval World by Martin J. Dougherty

Kings and Queens of Europe by Brenda Ralph Lewis

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

First published in 2018

This digital edition first published in 2019

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

United House

North Road

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2019 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-811-3

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

Contents

Introduction

1. Henry II

2. Richard I & John

3. Henry III

4. Edward I & Edward II

5. Edward III

6. Richard II

7. Henry IV & Henry V

8. Henry VI

9. Edward IV, Edward V & Richard III

Conclusion

Bibliography

Index

A representation of the enamel effigy of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, on his tomb at Le Mans Cathedral.

INTRODUCTION

According to legend, the Plantagenet royal line was literally the devil’s spawn. Their ancestor was the Count of Anjou, whose beautiful bride refused to attend mass. Confronted, she revealed herself as a devil and flew from the highest church window. All 15 Plantagenet kings were said to carry her demonic blood.

THIS COUNTESS of Anjou was alleged to be a daughter of Satan, or perhaps the serpent-fairy of medieval folklore, Melusine. One of the four sons she bore, was ‘Fulk the Black’, a notorious murderer and rapist who burned his wife at the stake in her wedding dress. Many believed the Plantagenets inherited their ferocious temper from Fulk; their golden-red hair came from Geoffrey the Handsome (1113–51), the future Count of Anjou and founder of the Plantagenet family line.

The French county of Anjou was the homeland of the Plantagenets, although few of its kings actually bore that name. Instead, it derived from the yellow broom plant, planta genista, a sprig of which was worn by Geoffrey on his hat. Geoffrey owned extensive territories in France, but did not rule, nor take any interest in England. That was instead the domain of his bride, Empress Matilda, widow of the Holy Roman Emperor and granddaughter of William the Conqueror.

Matilda was notoriously haughty and headstrong, and she wore her various titles with an arrogant pride. She therefore took it as a grave insult when her father, King Henry I of England, suggested she married Geoffrey of Anjou. Matilda’s last husband had been the Holy Roman Emperor, King Henry V of Germany, a powerful ruler who controlled a vast domain. Anjou, by comparison, was paltry, its heir a 15-year-old teenager. Matilda was 26 and a grand noblewoman in her prime.

The Great Seal of the Empress Matilda, heir to Henry I and wife of Geoffrey of Anjou.

Matilda, however, had no choice. Henry I did not have a male heir and hoped that Matilda’s marriage would supply a male to become the future Count of Anjou and King of England. In the meantime, Henry made Matilda his heir, a rare occurrence in an age when the line of succession was from father to son.

Many of the barons of England refused to accept the rule of a queen, and when Henry died in 1135 they invited Matilda’s cousin Stephen to seize the English throne. When Stephen did so it sparked a two-decade civil war known simply as ‘the Anarchy’.

A mock fight between cousins Matilda and Stephen, who both vied for the English crown.

During the Anarchy, the English barons fell in behind either Stephen or Matilda, and long periods of attritional warfare followed. To bolster his support, Stephen invited foreign mercenaries to England who, once there, committed brutal atrocities. It was during this dark period that ‘Christ and his saints slept’ according to the Peterborough Chronicle, a 12th-century Anglo-Saxon text.

‘They [the barons] sorely burdened the unhappy people of the country with forced labour on the castles; and when the castles were built, they filled them with devils and wicked men. By night and by day they seized those whom they believed to have any wealth, whether they were men or women; and in order to get their gold and silver, they put them into prison and tortured them with unspeakable tortures, for never were martyrs tortured as they were.’

– THE PETERBOROUGH CHRONICLE

The Peterborough Chronicle reported that the torturers hung people by their feet and smoked them over fires, or strung them up by the thumbs with chain mail armour strapped to their feet. Some had knotted cords tied to their heads, which were twisted until they broke through the skull; others were crushed in a shallow chest filled with sharp stones and stamped on; more still were simply thrown into dungeon oubliettes full of snakes, but with no food or water.

The war seemed to be about to end in 1142 when Stephen trapped Matilda in her castle in Oxford. His army laid siege for several months, and food inside grew perilously scarce. It was then, just before Christmas, that Matilda made a daring night-time escape dressed in a white cloak to camouflage herself against the snow. Her garrison surrendered the next day, but the deadlock of the Anarchy continued.

In the end, it took a male heir to resolve the English war of succession. This was Matilda and Geoffrey’s eldest son, the future Henry II, one of England’s most famous kings. Henry had all the characteristics typical of a Plantagenet: red-gold hair, a fiery temper and an insatiable desire to extend his power and lands.

Among Henry’s successors were the infamous English kings known so well to history: Richard the Lionheart, the Evil King John, and the nephew-murdering Richard III. Internecine murder and warfare is a hallmark of the Plantagenet story.

Here, Matilda performs her daring escape from Oxford Castle during the dead of night.

Henry II’s sons famously declared war on their father and nearly killed him with an arrow when he came to talk terms. As he handed over his kingdom to Richard, Henry snarled that he wished God would give him enough life to get revenge on his son.

Henry died a broken man, but he was one of the few Plantagenets to die of natural causes. Nor did many die a hero’s death on the battlefield. Dysentery was the leading killer, of kings as well as of common people. The most devastating medieval sickness was the 14th-century Black Death, which killed more than a quarter of the population; it took King Edward III’s daughters too.

The Royal Arms of England, shown here, were first adopted in the 12th century by the Plantagenet kings.

Edward was the romantic warrior king who fostered a national love of Arthurian legend and with it the ideals of chivalry. Edward held lavish tournaments known as Round Tables and led his army into war against the French. At Crécy, Edward wrought terrible devastation upon his enemy using thousands of archers with longbows; this new military tactic made the English army and its banner of St George the most feared in Europe.

St George and the three golden lions were only two of many symbols developed for the English kingdom under the Plantagenets. During their rule the Plantagenets transformed the cultural and political landscape of England: they built grand castles and gothic cathedrals, created the country’s parliament and its systems of justice, and made English, rather than French or Latin, the official language of government.

Many of the Plantagenets’ great castles remain standing today. Dover Castle, constructed by Henry II, is England’s largest.

However, these constitutional legacies don’t account for the dark appeal and lasting infamy of the Plantagenets. Rather it is their irresistible dynastic saga of murder, madness, betrayal and civil war. Few of the Plantagenet monarchs were good kings or decent men; but they are memorable monsters. Consider the catalogue of crimes and atrocities that occurred between the 12th-century Anarchy and the 1485 slaying of Richard III that ended the Plantagenet line.

These include: the murder of archbishop Thomas Becket by Henry II’s knights in Canterbury Cathedral; the 25-year squabble between Henry III and Simon de Montfort that resulted in the gruesome defilement of the knight’s body; the obsessional love between Edward II and Piers Gaveston that ended in the king’s alleged demise by hot poker; and the tyranny of Richard II leading to the Wars of the Roses, the most poetically named of England’s national bloodbaths.

The Wars of the Roses brought the Plantagenets full circle: their dynastic reign began during civil war and it would end during another. The end was as brutal as the beginning; it was perhaps a fitting conclusion. ‘From the devil we sprang and to the devil we shall go,’ Richard the Lionheart loved to say. This is the story of his family, the Plantagenets, the royal dynasty born of the demon Countess of Anjou.

The royal standard is laid at the altar at St Paul’s Cathedral following the Battle of Bosworth Field. Richard III, the last Plantagenet king, was killed during this battle.

Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket is confronted by the four knights who famously took his life in the cathedral.

1

HENRY II

King Henry II is best remembered for the bloody murder of Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. By chance or mishap, Henry infamously caused four knights to slaughter the priest in Canterbury Cathedral by crying: ‘Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?’

THE FIRST Plantagenet king never actually uttered the sentence about the ‘turbulent priest’. However, at the time, Henry was angry, drunk and tired after a long evening of feasting. What he actually said, moreover, was threatening enough. ‘What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household,’ he supposedly bellowed, ‘who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?’

Becket was indeed not of noble blood, but rather the son of a London merchant whose star was on the wane after a meteoric ascent through Henry’s court to the highest religious office of the land. Not that any of this mattered to the four knights who sat earnestly through Henry’s tirade and concluded it to be a direct order from their sovereign. They immediately set out at a hard gallop from Henry’s court in Bures, Normandy, to Canterbury and reached the cathedral a few days later.

Becket was in his inner chambers at dusk on 29 December 1170, when the heavily armed knights burst through his door. An argument broke out and Becket retreated, hurrying away to hear vespers. Now angry, the knights followed Becket into the cathedral and attempted to drag him outside. Becket resisted, crying out that if they wished violence upon him they would have to carry it out there, on consecrated ground. He grabbed a nearby pillar and held on for his life.

Henry II had inherited both the Plantagenet golden-red hair and the fiery temperament: his tantrums were legendary.

Swords were then drawn and Becket was struck with the flat of one knight’s sword. ‘Fly! You are a dead man,’ he told Becket as another dealt him a blow on his head. Blood streamed down Becket’s face and he fell to his knees. Another knight then swung at Becket with such force that he cut off the top of his skull and shattered his blade against the stone floor. The others proceeded to butcher Becket where he lay, one using his sword point to spread around the Archbishop’s brains. He then called out to his comrades: ‘Let us away, knights; he will rise no more.’

Standing in stunned silence in the shadows of the cathedral were Becket’s ecclesiastical staff. These were the men who would report the atrocity to the horrified ears of European Christendom. None were excluded from the appalled condemnation of Henry that followed. Louis VII of France, who had earlier lost his bride Eleanor to Henry and hated him passionately, demanded ‘unprecedented retribution’. ‘Let the sword of Saint Peter unleashed to avenge the martyr of Canterbury,’ Louis wrote.

The Becket Casket is a 12th-century gilt-copper and champlevé enamel reliquary depicting the murder of the Archbishop. Its contents are no longer present.

It would take three years for Becket to be canonized, but in the meantime his martyrdom was an instantaneous scandal. The people of Canterbury rushed to the murder scene waving pieces of cloth that they dipped in his blood and then tasted, and in some cases, put into their eyes. Sensing the possibilities, the priests of Canterbury immediately struck up a thriving trade in Becket’s blood. It was gathered and mixed as a tincture, heavily diluted with water, and sold in small, custom-made alloy vessels with the inscription ‘All weakness and pain is removed, the healed man eats and drinks, and evil and death pass away.’

This badge of Thomas Becket’s head was a common souvenir sold to pilgrims visiting his shrine at Canterbury Cathedral. The badge proved that the pilgrim had made the journey and was said to heal the sick or dying.

For those not able to afford a vial of Becket water, brooches and pins depicting the Archbishop’s likeness also became available. A kind of cult of Becket was created and pilgrims with mysterious ailments including cankerous sores and swollen limbs made long pilgrimages to his tomb. Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales is based on these pilgrims. Any member of the unwell who did not receive a healing miracle via the dead Becket was simply told they lacked the inherent faith to begin with. Nothing would slow the multitudes of pilgrims or the publicity it generated for Becket’s martyrdom; news of his murder spread quickly.

The irony was that Henry seemed as shocked by the news of Becket’s death as everyone else. After all, they had once been favourite friends. But more than that, Henry understood exactly what the fallout from the murder would entail: it would leave him as a pariah. He took to his bed for three days and refused food or water. He then set off for the furthest corner of Western Europe where he could stay out of view: Ireland.

THE KING’S BEGINNING

The Kingship of England had been one trial after another from the moment Henry, Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, took the throne at 21. Henry inherited his father Geoffrey of Anjou’s golden-red hair and a propensity for violent and vindictive rages. During one such fit, Henry ‘flung down his cap, undid his belt, threw from him his cloak and robes, tore the silk covering off his couch, and, sitting down as if on a dunghill, began to chew stalks of straw.’

Volatile and unpredictable anger was the characteristic that united all of the Plantagenet kings. On the one hand, Henry could be charming and held the wit and courtly courtesy expected of a medieval royal; he also dressed like a huntsman and was quick to take violent offence if he believed his authority undermined.

Henry was ruthlessly ambitious and his mother Matilda had urged him from boyhood to seize his birthright of England. In his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry had met an equal in ambition: the union brought great wealth to both parties and was also one of the great royal scandals of the age.

DESCRIBING THE KING

A CONTEMPORARY DESCRIPTION OF Henry comes from the Archdeacon of Brecon and historian Gerald of Wales, who wrote an account of the king’s 1171 conquest of Ireland. Although something of a panegyric, it does confirm other accounts of the king’s vigour and his apparent inability to sit still.

‘Henry II, King of England, was a man of reddish, freckled complexion with a large round head, grey eyes which glowed fiercely and grew bloodshot in anger, a fiery countenance and a harsh, cracked voice. His neck was somewhat thrust forward from his shoulders, his chest was broad and squat, his arms strong and powerful…He was addicted to chase beyond measure; at crack of dawn he was off on horseback, traversing aster lands, penetrating forests and climbing the mountain tops, and so he passed restless days. At evening on his return home was rarely seen to sit down either before or after supper. After such wearisome exertions he would wear out the whole court by continual standing.’

– Expugnatio Hibernica, Gerald of Wales

The Great Seal of King Henry II shows the king on his throne and astride his horse. Henry’s passion for riding made him bowlegged over time.

The traditional role of princesses during the Middle Ages was to be married off as a way of brokering an alliance between two great households. This could increase the wealth and assets of both or otherwise heal a rift that had previously resulted in conflict. Eleanor, however, was a rare combination of a keen brain and captivating beauty; medieval students in ale houses often sang bawdy songs about bedding her. Eleanor’s lands of Aquitaine, which covered a vast swathe of western France, were prize enough in themselves for any royal suitor. Eleanor was, in short, the greatest catch of the 12th century.

VOLATILE AND UNPREDICTABLE ANGER WAS THE CHARACTERISTIC THAT UNITED ALL OF THE PLANTAGENET KINGS.

King Louis VII of France wasted no time in marrying Eleanor himself, but the union was to be a disappointment for both newly-weds. Eleanor bore Louis two daughters but was unable to produce a needed male heir. Besides, Eleanor was a feisty, extravagant queen who loved luxury. Louis, by comparison, dressed drably and stuck to a simple diet. Eleanor once remarked: ‘I’ve married a monk, not a monarch!’ In the end, it was Eleanor who sought an annulment from Louis. To add insult to this injury, Eleanor was soon riding to the bedside of her next betrothed: Henry. The journey was dangerous, as several nobles had set out to kidnap Eleanor and force her into marriage, so desirable was her hand.

Eleanor’s marriage to Henry brought experience and sophistication to match the Plantagenet brawn: Eleanor was 30, Henry 19, and both wanted the world. With their territories combined and the lands later conquered by Henry, the couple would rule over a kingdom that stretched from Scotland to the Pyrenees; it represented the height of the Plantagenet’s physical dominion. Eleanor’s ambition, however, would prove to be Henry’s undoing.

Henry II and Eleanor are depicted riding into Winchester on their way to the king’s coronation in London.

Nevertheless, when Henry landed on the shores of England to claim the English throne and quell the civil war that had wracked the country for 16 years, it must have been a comfort to know Eleanor was standing steadfast beside him. England at that time was not a particularly desirable proposition. Henry landed at Malmesbury in Wiltshire, a town loyal to his enemy, King Stephen, with a small army numbering around 3000 infantry and 150 knights.

Henry’s winter crossing of the English Channel had been tempestuous, and he marched towards Malmesbury in a filthy mood. The castle itself was half-ruined after three years of siege. Inside, the exhausted inhabitants prepared, once again, to defend their town as Henry planned how to destroy it. The Gesta Stephani, a history of King Stephen, recounts the action:

‘So the Duke [Henry] collecting his forces, and with the barons flocking in eagerly to join him, made without delay for the castle of Malmesbury, which was subject to the king, and when a crowd of common people flew to the wall surrounding the town as through to defend it he ordered the infantry, men of the greatest cruelty, which he brought with him, some to assail the defenders with arrows and missiles, others to devote all their efforts to demolishing the wall.

When the town of Malmesbury was captured…behold, not long afterwards the king [Stephen] arrived with a countless army collected from all his supporters everywhere, as though he meant to fight a pitched battle with the duke, as the armies of both sides stood in array with a river dividing them it was arranged between them and carefully settled that they should demolish the castle, both because they could not join battle on account of the river and its very deep valley intervening and because it was a bitter winter with a severe famine in those parts.’

– GESTA STEPHANI

This map shows the extent of the Plantagenet kingdom directly after Henry II took the English crown.

Severe famine, civil war, a bitter winter. It’s a bleak picture of a broken England, a state torn and rudderless, desperate to be reconciled and reunited. Understanding this, Henry employed diplomacy rather than bloodshed to bring the English to his side. First he sent his mercenaries home – the English loathed the foreign fighters who had robbed, harassed and murdered so many during the Anarchy. Next he invited Stephen to parley. This was done more out of necessity than guile: expecting Henry’s attack to come at Wallingford Castle rather than Malmesbury, Stephen had led his army on a forced march for the 80km (50 miles) between the two.

An illustration depicting the meeting between Henry and Stephen across the River Thames. Their deal saw Henry crowned King of England less than a year later.

By the time Stephen reached Malmesbury his army was drenched and harried by a biting wind. Many could not hold their dripping wet lances. They outnumbered Henry’s men, but none had the stomach for a fight. The civil war had all but burnt itself out. In the end Stephen agreed to negotiate with Henry. Their agreement, called the Treaty of Winchester, promised that Henry could become King of England, as was his birthright, but only after Stephen had died. This turned out to be providential, as less than a year later Stephen complained of ‘a violent pain in his gut accompanied by a flow of blood’ and collapsed shortly afterwards. Henry was crowned at Westminster Abbey alongside Eleanor on 19 December 1154.

KING HENRY

King Henry II still had a lot to do in England. Under Stephen, many castles, towns and land had been given away to foreign lords in return for support of arms. Henry ordered the expulsion of all foreign mercenaries who had benefited from these favours, in particular the hated Flemish. He then began to demolish the many illegal castles that had sprung up during the Anarchy. Next, Henry went head to head with other barons plotting rebellion.

The most notable of these was Hugh de Mortimer, owner of four castles including Wigmore, who refused to swear fealty to Henry. The king marched his army to Wigmore, but in another display of diplomatic finesse, declined to give the order to attack. Instead Henry paused just long enough outside the castle for a panicked Hugh to wave the white flag. Even then, Henry did not punish the baron. Instead he rode his army into the castle and straight back out again. Henry was sending a clear message to Hugh and any other baron contemplating treason: he was the king and in England his control was absolute.

The remains of Wigmore Castle, stronghold of rebel baron Hugh de Mortimer. Mortimer would proclaim his loyalty to Henry without a drop of blood being spilled.

IN HIS REFORMS HENRY UNWITTINGLY INSTITUTED A LEGAL SYSTEM THAT TODAY FORMS THE BASIS FOR LAW IN BOTH BRITAIN AND THE UNITED STATES.

Shows of force were a useful temporary measure; a more systematic strategy was needed to create lasting stability. Henry had to find a way of both humouring and taming the barons. To do this he assembled an entirely new type of army: one made up of law clerks. Law would become Henry’s weapon of centralized control, and he would administer it by means of travelling judges in each of England’s counties. Up until then justice had been the domain of the sheriffs. English law itself was a hotchpotch of rules introduced by the Normans to oppress the English alongside the more ancient customs enacted by the Anglo-Saxons.

To dispense Henry’s justice, travelling judges, known as ‘assizes’, would arrive in a town or village, proceed down the high street with the sheriff and other dignitaries in tow, and then sit at a local hall to overhear a case. The judges would return to their headquarters at London’s Westminster Hall and compare notes with colleagues who had been administering justice in other parts of the realm. These discussions and the punishments served for crimes laid out a common set of principles, or precedents, which aimed to ensure consistency in the administration of justice. In time this became known as common law.

One of the responsibilities of the judges was to resolve disputes over land. This was a common problem in 12th-century Britain, a rural society whose central interest lay in dominion over arable land. For these cases, the judges would instruct 12 men to help them with the case and offer advice – a jury. Trial by jury thereafter replaced trial by battle and trial by ordeal, the previous means of settling disputes. In his reforms Henry unwittingly instituted a legal system that formed the basis for law still used today in both Britain and the United States.

TYPES OF TRIALS

TRIALS BY ORDEAL AND battle were legal methods, introduced by Anglo-Saxons, which left it to God to determine a person’s guilt or innocence. Ordeals were normally used when no other evidence, such as eyewitness accounts, was available. There were three such trials: by hot water or hot iron, by cold water, and by consecrated bread. All were administered by a priest in a church before witnesses.

In a trial by hot water, the accused was invited to pick up a stone from the bottom of cauldron of boiling water. In a trial by hot iron, the accused was asked to carry a red-hot piece of iron across a specified distance. In both cases, the accused was considered innocent if after three days God had healed the wounds rather than let them fester.

In a trial by cold water, the accused had their feet and hands bound and were then thrown in a river, pond or sanctified water. If the accused floated they would be declared guilty; if they sank, innocent. The rather more benign trial by consecrated bread was a way of testing the innocence of a cleric. The accused would be asked to swallow a piece of bread, and, if it made them choke, God was showing them to be guilty.

The Normans’ usual method of resolving a dispute over land or money was trial by battle, a duel between the two parties with the winner said to be the one favoured by God. The loser of the battle, if still alive, would often then be executed as punishment.

Villagers carry out a trial by cold water. The trial seldom ended well for the accused.

None of Henry’s legal reforms were enacted for the common good of his ordinary subjects. They were created simply to control the populace and fill the king’s coffers. Fines and other payments for breaking the law went straight to Henry; barons and other wealthy men were expected to give the king a monetary gift to grease the judicial cogs. In his legal reforms, therefore, Henry had successfully placed his barons under the royal thumb while also turning a healthy profit. However, his judicial reform could not reach the institution that had long been a rival for power with European monarchs: the Church.

In the 12th century, nearly one in six Englishmen belonged to the clergy. Many were poor, badly educated and even illiterate, but all enjoyed protection under the Church against criminal punishment. Clergymen, in other words, who stole, raped, maimed or killed, would receive their sentence from the Church’s own papal court – and the Church had a well-founded reputation for lenient treatment of its own. The exemption of clergymen from his new laws enraged the king; he regarded it as an insult to his regal authority. The Church would have to be dealt with.

A 12th-century depiction of prisoners awaiting trial in stocks and tethers.

An opportunity presented itself in 1161, with the death of Theobald the Archbishop of Canterbury. To bridge the gap between Crown and Church, Henry could install his own candidate. This was of course his friend and chancellor and the man he would later murder: Thomas Becket.

BROTHERS IN BLOOD

Becket impressed Henry from the moment they met. He was a clerk for Archbishop Theobald, and Henry was immediately struck by his confident and pragmatic approach. The two became famous friends, hunting partners and drinking companions. Before long, Henry had made Becket his chancellor.

It was a match of opposites: Becket was tall, dark-haired and pale with a long nose who, despite being of common stock, styled himself as a wealthy nobleman of importance. His patrician style was the perfect foil for the squat, ruddy king, who hated pageantry and courtly ceremony, and indeed, anything that might confine him to sitting still.

Henry teased Becket about his fine clothes. Once, when riding through the snow-covered streets of London, Henry remarked that it would be a charitable thing to give a nearby shivering beggar a warm cloak. When Becket agreed that it would, Henry tore the cape from his chancellor’s back and threw it to the beggar. Henry took pleasure in irritating the pompous Becket; he would ride his horse into Becket’s dining hall before leaping from the saddle to eat. However, Henry was also pleased to leave his chancellor in charge of court pageantry, at which Becket excelled.

Thomas Becket is shown in conversation with Henry II in Peter Langtoft’s 13th-century Chronicle, a history of England.

THE PARIS TRAIN

BECKET’s biographer and travelling companion William Fitzstephen describes one of the Chancellor’s trips to Paris. For such excursions, Becket travelled with a train of pack horses, carts and servants and brought gifts of jewellery, clothes and even monkeys to King Louis VII. Designed to dazzle all who witnessed the procession, such trips were publicity stunts paid for by Henry and executed by Becket:

‘Eight wagons conveyed all the requisites for the journey, drawn by five high-bred horses; at the head of each horse was a groom on foot, “dressed in a new tunic.”…The Chancellor’s chapel-furniture had its own wagon, his chamber had one, his pantry another, his kitchen another; others carried provisions, and others again the baggage of the party; amongst them, twenty-four suits of clothing for presents, as well as furs and carpets. Then there were twelve sumpter-horses; eight chests containing the Chancellor’s gold and silver plate; and besides a very considerable store of coin, “some books” found room…two hundred and fifty young Englishmen led the way in knots of six or ten or more together, singing their national songs as they entered the French villages…lastly came the Chancellor himself, surrounded by his intimate friends. “What must the King of England be,” said the French as he went by, “if his Chancellor travels in such state?”’

– THE LIFE AND MARTYRDOM OF SAINT THOMAS BECKET, WILLIAM FITZSTEPHEN

Thomas Becket is shown at the head of his ostentatious train as it makes its way through France towards Paris.

With his interest in ostentatious displays of power and material wealth, it is perhaps understandable that many of England’s clerics found Becket a poor fit for the job of Archbishop of Canterbury. He wasn’t exactly monastic in his approach. There were other objections to the appointment: Becket’s academic record was poor, he was too close to the king, he appeared by all accounts to be a secular figure, and had previously been verbally abusive to the monks while working for Theobald. Even Becket was unsure about his own credentials. He was, however, an ambitious man who did nothing by halves. If the king wanted him to be the archbishop, then he would be the archbishop, and he would make it his life’s work.

Becket’s religious detractors shouldn’t have worried, for when Henry made him archbishop, he embraced his new role with a passionate fanaticism. First, Becket resigned as chancellor as he felt the two roles to clearly be at odds with each other. With the chancellorship went the 24 silk suits he had taken to Paris, and any other material that might be considered a vanity. Instead, he switched to austerity, as William Fitzstephen explains: ‘Clad in a hair shirt of the roughest kind, which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin, he mortified his flesh with the sparest diet, and his accustomed drink was water used for the cooking of hay…He would eat some of the meat placed before him, but fed chiefly on bread.’

Thomas Becket is here immortalized in the middle stained glass window at St David’s Cathedral, Wales.

Thomas Becket took his role as Archbishop of Canterbury seriously: he washed the feet of beggars daily and wore a hair shirt.