17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

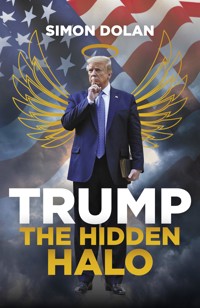

According to most of the media, the left and the political establishment, Donald Trump was a racist, sexist, dangerous man who debased the office of US President, embarrassed his country and brought it to the brink of civil war. Throughout his administration, the contempt in which the billionaire businessman and TV personality was held across the Western world led to sneering at any alternative view. And yet Trump came within inches of re-election, and had it not been for the coronavirus pandemic he almost certainly would have succeeded. Undeterred by all the noisy vilification, more than 70 million Americans formed their own view – and they liked what they saw. Now, determined to redress the balance of a fiercely partisan debate, Simon Dolan, a multi-millionaire British businessman and entrepreneur, looks behind the hyperbole to offer a very different take on Donald J. Trump. Just what were the achievements and personality traits that appealed to voters in their millions? Trump: The Hidden Halo sets out to reconsider this most divisive figure through the eyes of those who supported him. Looking to his economic record, the impact of 'America First' and the effect of his bombastic approach to foreign policy, this timely consideration of Trump's appeal to the masses presents the man in a new light: did he have a hidden halo after all?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 541

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

iii

TRUMPTHE HIDDENHALO

SIMON DOLAN

v

To the American Republic and the people who defend it.

CONTENTS

FOREWORDBY NIGEL FARAGE

What will Donald Trump’s legacy be? After four tumultuous years, most contemporary commentators will want to focus on the storming of the Capitol on 6 January 2021. When the mob walked up the steps of the Capitol, the President’s opponents had the moment they had been waiting for, and they will never let it go. Yet that awful episode did not define Trump’s presidency and should not overshadow all he achieved. From the announcement of Trump’s candidacy in 2015 to the end of his administration, the Establishment never gave the man who became 45th President of the United States a chance. Early ridicule turned into obsessive condemnation: the phenomenon of ‘Trump Derangement Syndrome’, which dictated that nothing he ever did was right.

I joined the Trump train in 2016, shortly after the Brexit vote. What I saw was a big personality, full of charisma and – rather to my surprise – charm. I saw a man prepared to take on corrupt elites: a process he knew would be difficult and ugly but was ready to embrace.

At that point, few in Washington took Trump seriously. When, in November 2016, he beat Hillary Clinton, they were in shock – and they stayed that way throughout his tenure. The joke candidate was heading for the White House, and they couldn’t believe it.

Trump had come right out of left field. Though he attended an elite college – the University of Pennsylvania – he is not classic Ivy xLeague. Indeed, he did not excel at school, eventually graduating from college without honours. Disconcertingly for the Washington elite, he had never been involved in mainstream politics. In fact, until the age of seventy, he had not held a single elected office at any point in his life. Before entering the world of showbiz, he’d had a gun-slinging career as a New York real estate guy, where, on occasion, he had to run the gauntlet of the mob. It was rough and tough, and he had to duck and dive to thrive. He developed important life skills, but not of the kind that were appreciated by the liberal elite. There had never been a modern American President with such an unpresidential background, and that is partly why he was so loathed by the media: he was simply not one of them. He was completely different to anything they had encountered in national politics, and they could not accept his rise.

It was not just his background but his language and vocabulary that offended them. The way he spoke alienated the affluent, educated New York, Washington and Los Angeles types. He didn’t sound like a politician, and they interpreted his limited use of vocabulary and habit of repeating himself as a sign of stupidity. It was a lazy and offensive assumption. Having spent a significant amount of time with him over the years – sat with him over dinner; talked to him over the phone; appeared at his rallies – I have no doubt that he is incredibly sharp. I was struck by the ease with which he understood the impetus for Brexit: while many European leaders struggled to grasp why millions of British people might want to leave the EU, Trump instinctively understood the desire for freedom from overbearing, distant, bureaucratic institutions. Such was his hatred of globalist corporate structures that sometimes I thought he was more Eurosceptic than I am.

Trump was a leader guided by principles: first and foremost, the fundamental right of sovereign nations to put the interests of their people first, while working with other nations to stamp out war and injustice and promote global prosperity. I remember watching his xi2018 speech to the United Nations. At the time I was still a Member of the European Parliament and was listening to him from Brussels. He spoke simply and plainly about the existence of the nation state and why it was the only model that allowed democracy to flourish. That speech defined him. When historians ask, ‘What was Trumpism?’, the answers are in that speech. He was driven by a firm belief that globalist bureaucracies are expensive and unresponsive and that their power needs to be controlled.

One of his greatest attributes was his natural affinity with voters with whom – ostensibly at least – he had nothing in common. This was not fake: he really did care about the challenges faced by ordinary hard-working Americans, particularly those living in old industrial areas, as they tried to build better lives. I remember sitting with him in Trump Tower, with its lavish gold-inlaid front door, surrounded by Roman-Emperor-scale wealth. There he was, in his magnificently opulent surroundings, talking passionately about the struggling workers of America’s Midwest. For all his wealth, he was a blue-collar billionaire, instinctively in tune with the ordinary ‘American Joe’. It led to the most appalling snobbery against him. In tones of derision, the commentariat would call him a truck driver, as if driving a lorry should be a source of shame.

During his presidential campaign in 2016, Trump made a series of promises to the American people that he intended to keep. In the White House, he was as good as his word. I remember going into the West Wing in February 2017, when he had been in office for just over a year, and seeing a big whiteboard listing all his election promises. Next to each pledge was a tick or a timetable, setting out what had been delivered and what remained to be done. I told him that I thought he was helping to restore faith in the democratic process. ‘I’ve kept more promises than I’ve made!’ was his proud response.

During the 2020 presidential election campaign I was surprised and honoured when he invited me to join him on stage at a rally in xiiArizona. Addressing thousands of his supporters, I called him the bravest man I know, for his sheer resilience and will against a vicious media and the Washington DC swamp. Against overwhelming opposition and the determination of powerful vested interests to portray everything he did in the worst possible light, he never wavered from his principles: to do everything he could to stand up for forgotten and marginalised American voters and make his country great again.

Naturally, I was castigated for my tribute to Trump that day. But as I read Trump: The Hidden Halo, I realised that my words in Arizona were correct. As this powerful and important book sets out, his achievements during his four years in office were remarkable. The Hidden Halo charts the battles he faced and shows how, in most cases, he overcame extraordinary obstacles to deliver for the American people. It gives him the fair hearing he was consistently denied and the credit he deserves.

Nigel Farage February 2021

INTRODUCTION

How will Donald Trump be remembered? Thanks to his response to the outcome of the 2020 election and the awful scenes in Washington when his supporters stormed the Capitol, there has not exactly been a clamour to make a positive case. Frustratingly for those who believed he was doing great things for his country, his strategic errors in the final weeks of his presidency played directly into the hands of everyone who had always despised both him and his supporters.

Yet, as the 74 million Americans who wanted to give him a second term know, the 45th President of the United States was so much more than the circumstances surrounding his departure. To many he remains a hero. This book explores why.

I’d never been interested in politics in general – still less what goes on in Washington – until Trump entered the White House. I’d always taken the view that politicians on both sides of the Atlantic, and almost everywhere else for that matter, are either corrupt or incompetent, or indeed both. Surveying the quality of Members of Parliament in the UK, especially during the years of chaos when the government struggled to implement the result of the Brexit vote, just made me depressed. These elected individuals rule us, I thought resentfully, but most of them seem so useless, I doubt they could get any other job.

All my life, I’ve disliked being told what to do, which is probably why I have always run my own businesses rather than work for anyone else. The fact that these clowns had so much power and xivauthority annoyed me. However, there didn’t seem much I could do about it, so, like millions of other people, I switched off.

Then, in 2015, reality TV star and New York real estate mogul Donald Trump decided to run for office. This piqued my interest. Of course, he had no chance of winning: even his own party was against him. The ‘Never Trumpers’ in the Republican movement dismissed him as an embarrassment and a joke. Initially, the media was amused but wrote his candidacy off as nothing more than a publicity stunt. It wasn’t until later, when it became apparent that his campaign was gathering ground, that they started to panic.

As for me? I started to think: what if? What if a businessman actually got to run a country, rather than one of the dull, standardissue, ‘normal’ politicians?

In my mind, this was only ever a thought experiment. The badass in me liked the idea of this swaggering figure wrongfooting all the naysayers, winning by a landslide, then going into the White House and smashing everything up. I didn’t crave wanton destruction, or the arbitrary jettisoning of carefully crafted policies that had been proven to work; I just liked the idea of a charismatic outsider doing things differently, challenging the status quo.

Imagining this scenario became a kind of guilty pleasure. Like almost everyone else, I assumed Democrat candidate Hillary Clinton would win by a landslide. After all, when Trump entered the race, the front page of his hometown newspaper, the New York Daily News, declared that a ‘clown’ was ‘running for Prez’. They chose the worst picture of him they could find and mocked it up with a stupid painted smile and a big red nose. They used variations of this image time and again, under front-page headlines labelling him ‘Dopey’, ‘Brain Dead’ and – when they thought he was about to lose – a ‘Dead Clown Walking’.1 Broadsheet newspapers may have used fancier language, but they were no less brutal in their character assassinations. Cover to cover, they routinely depicted the prospect of a Trump presidency as both improbable and a disaster.

xvIt was not just the media but almost everyone else with a platform or voice. Hollywood hated him. Rappers who once idolised him as a boss man, the personification of brash self-made success and an icon of shameless bad taste and bling, suddenly decided he was a dangerous racist. In April 2016, hip hop artists YG and Nipsey Hussle released a song called ‘FDT’ (F*** Donald Trump), featuring disobliging soundbites from a bunch of black students who had been ejected from a Trump rally in Georgia. It took the pair less than an hour to record, yet the Los Angeles Times declared it ‘the most prophetic, wrathful and unifying protest song of 2016’.2 The bien pensants in the City of Angels, and everywhere else, had decided Trump was the devil – and should be sent back from whence he came.

Surveying the relentlessly hostile commentary, I felt sure that, come autumn 2016, he would be heading back to his old life as a reality TV star.

Yet something strange was happening. That summer, following his official nomination as Republican candidate, Trump’s campaign, which I’d read was chaotic and run by complete novices who had no idea what they were doing, began to gather momentum. At Trump rallies, the crowds seemed to love him. There was an energy and excitement around him. He spoke for voters who felt forgotten. This was broadening out into a powerful anti-Establishment movement.

As his campaign picked up pace, he took aim at the cosy elites and the ‘Washington swamp’3 – and they fought back. I watched, fascinated, as they threw everything at him. They spent tens of thousands of hours and millions of dollars trying to dig up dirt. Of course, anyone who runs for such high office can expect every aspect of their life and background to be raked over, and rightly so. But the treatment of Donald J. Trump was off the charts. Celebrity A-listers were threatening to leave the country if he got in. It was months until the election, but hysterical left-wingers were already trying to figure out how to impeach him. All this struck me as very odd. If he was such a joke, why were they so scared? Did they think he could actually win?

xviI’ve always loved an underdog. Now I was really engaged. And then it happened. I was in a hotel in London on 9 November 2016. I turned on the TV in my room and saw news anchors in tears, people rioting, celebrities in a panic.

What natural disaster had occurred? Had Obama died? What could have caused this? It turned out that nobody had been hurt. What had happened was that Trump had done the unthinkable: he had won. The butt of a million jokes was now the President-elect of the United States.

My wish had been granted. A businessman was now running a country. Not any country but the most powerful on earth. That morning, I felt a sense of excitement, anticipation and mischief. One in the eye for the Establishment.

While I was excited about what lay ahead, I knew that mighty forces were stacked against him. They would stop at nothing to get him out. This time, there would be none of the usual warm words from the losers about giving the victor the benefit of the doubt. There would be no temporary suspension of hostilities while the country came together to celebrate the dawn of a new political era in a spirit of unity and hope. As an outsider, all I could detect among the political classes and commentariat in America was fear, horror and disbelief.

As for ordinary American voters? Millions were euphoric. They felt as I did: that this much-reviled and derided figure might actually do some good.

In the years that followed, I watched in disbelief as the worst possible complexion was put on Trump’s every utterance and move. As far as the liberal elite and their media mouthpieces were concerned, he could simply do no right. To me, the way he was publicly judged made no sense. In 2009, Barack Obama, whose foreign policy attracts little praise from historians, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Obama had been in office for just nine months when he received the prize, acquiring it for ‘extraordinary efforts to strengthen xviiinternational diplomacy and cooperation between people’. Apparently even he was surprised. ‘To be honest, I still don’t know what my Nobel Peace Prize was for,’ he has said.4 Former secretary of the Nobel Peace Prize committee Gier Lundestad has since hinted that the decision was a mistake.

To me, this says it all. At the same stage in his presidency, Trump was embroiled in a witch-hunt over allegations of conspiracy with Russia, whipped up by vested interests determined to discredit him. According to the conspiracy theory, this President was not just stupid, ridiculous and racist – he was a traitor. Unlike Obama, who waged military campaigns in Somalia, Yemen, Libya and Syria and failed to extract the US military from either Iraq or Afghanistan, Trump started no new wars during his tenure in the White House – at least not of the conventional military kind. To me, a cool assessment of the facts suggests that he achieved more in foreign policy terms than any of his recent predecessors. Yet, to date, he has received no international recognition for his efforts whatsoever.

Even among Republicans, there has been a wilful blindness to anything positive he achieved. At times, the hypocrisy has been extraordinary. Of course, Trump didn’t help himself: quite the reverse. It is evident from multiple authoritative insider accounts of his administration – and indeed his own Twitter account – that the way he treated some of those who worked for him, those people having given up highly rewarding careers in finance and other fields to support him and his administration, left a little to be desired. He ruffled the feathers of decorated military men, captains of industry and all sorts of other distinguished experts and professionals. The way he spoke about other world leaders could come as a shock. When he behaved like this, the word most often used, even by those who sought to see the best in him, was ‘unstatesman-like’ – and perhaps they were right.

This book is not going to pretend that none of that happened, or that his verbal tirades were not sometimes ugly. I have not set out xviiito reveal that Donald Trump secretly loves small babies and kittens, nor that he makes midnight visits to hospitals to comfort cancer patients. I doubt he has ever volunteered in a soup kitchen, doled out bags of pasta at a food bank or paused to listen to the life story of a homeless man on the street. That is just not him.

What I am interested in is not his character but what he actually achieved. His army of detractors spent four years playing the man not the ball. Now he is off the pitch, it seems worth studying his best moves. This book seeks to separate his policies from his divisive personality. A long line of smart, successful and very well-informed people have articulated the case for the prosecution of Donald Trump, including those who have a great deal of expertise in the aspects of his administration they have examined. Precious few have made the case for the defence. This book sets out to redress the balance.

This man said he was not ‘President of the World’ but President of the United States, and he would put ‘America First’.5 I want to make the case that, in many ways, Donald J. Trump did just that. In November 2020, 74 million American voters thought he deserved a second term – so it seems they agree.

Some will ask what qualifies me to attempt such an assessment. The answer is nothing more than the impartiality of an outsider who has no vested interest whatsoever in putting an unduly positive gloss on these events. I do not claim to be an international trade or foreign policy specialist, nor even an economist. Then again, neither are the vast majority of Americans who determine the outcome of presidential elections. And perhaps the fact that we are not experts gives us some advantage. ‘Experts’ have become an increasingly important part of our lives, but how often do they actually turn out to be correct? If ‘expert’ economists actually understood as much about the real world as they think they do, then they would be billionaire traders. ‘Expert’ foreign policy advisers have presided over an awful lot of wars. The same can be said for xixthe war on drugs, the war on poverty and so on. Experts abound, but they often achieve little to nothing. Finally, of course, we have Covid. How many expert opinions on the pandemic have been proven wrong?

Sometimes what is needed is less ‘expert’ opinion, and more basic common sense. But then I would say that – I am not an expert.

Among all those who bitterly resented the decision of some 63 million American voters to put Trump in the White House in the first place, there is an overwhelming sense of relief that he is gone. The brash showman with the vulgar taste for big suits, sunbeds and colossal chandeliers has been stripped of power. The ‘basket of deplorables’ who supported him have been put back in their place. As Joe Biden begins his presidency after the most toxic election in modern American history, those who always wanted Trump out of the White House will hope that his departure will usher in a new and much less divisive era. They would like to imagine that the 45th President was some kind of aberration, and that all those Americans who felt he understood their worries and somehow shared their hopes and dreams will simply retreat to the shadows, ashamed that they ever fell for his mesmerising sales pitch.

I am not so sure. Trump’s supporters have had a taste of a very different kind of leadership, and, for all his faults, they loved it. It seems probable that their continuing belief that the election was rigged and sense that their hero was hounded out of office will only exacerbate the grievances that propelled him to power in the first place.

As for all those who are celebrating the end of his administration and think Biden is the answer to America’s problems, perhaps the passage of time will inject some much needed perspective. With the benefit of hindsight, might they come to realise that the man they painted as the devil actually had a hidden halo?

Simon Dolan February 2021

xx

NOTES

1 Elise Viebeck, ‘A visual history of Trump’s battle with the N.Y. Daily News’, Washington Post, 10 February 2016.

2 August Brown, ‘“I feel good for speaking up”: YG on his 2016 protest anthem that goes after Donald Trump’, Los Angeles Times, 17 November 2016.

3 ‘Trump in Ocala: “I never knew the Washington swamp was this deep”’, Bloomberg Quicktake [video], YouTube, uploaded 16 October 2020.

4 Heather Saul, ‘Barack Obama on Stephan Colbert: “To be honest, I still don’t know what my Nobel Peace Prize was for”’, The Independent, 19 October 2016.

5 Mythili Sampathkumar, ‘Donald Trump puts “America First” stating he is not “president of the world”’, The Independent, 5 April 2017.

PART ONE

FIGHTING THE GOOD FIGHT2

1

ALIENS – TRUMP AND IMMIGRATION

The big, beautiful wall. What a striking image. Whether you like the idea or not, it’s easy to visualise. For me, a wall serves to keep intruders out. It’s a physical barrier to stop people going where they are not entitled to go. To Trump’s detractors it was a symbol of cruelty and racism.

All countries have borders. Indeed, a country ceases to be a country if it does not have borders. Like many Presidents before him, Trump simply wanted a border that actually worked. Border patrol wanted one that worked. Legal immigrants wanted one that worked. Most American voters wanted one that worked. Some likened it to the Berlin Wall. Of course, that particular wall was designed to keep people in not out. Do you have a wall or a fence around your house? Does that make you racist or simply sensible?

In spring 1989, New York lived up to its regrettable reputation as one of the most dangerous cities in the world when two women were raped and almost killed in unconnected attacks that took place within three weeks of each other. The first victim, aged twenty-eight, was jogging through Central Park after dark when she was violated, beaten to within an inch of her life and left for dead in a shallow ravine. After she was discovered, she spent twelve days in a coma before regaining consciousness. The second victim, aged thirty-eight, was robbed by three teenagers who then coerced her onto a 4rooftop in Brooklyn. There, she was brutally assaulted before being thrown down a 50ft air shaft. Like the woman who was attacked in Central Park, her survival was considered miraculous.

Any rape is indescribably appalling, but the first of these two cases received significantly more public attention than the second. The US commentariat generally attributed this discrepancy to the fact that the Central Park jogger was a white middle-class American, whereas the woman assaulted in Brooklyn was a Jamaican immigrant. Among a number of high-profile figures drawn into this row was Donald Trump. His personal reaction to these two shocking events is early evidence that he is not, as his critics constantly claim, fundamentally and intrinsically ‘anti-immigrant’ – still less anti-immigration per se.

When the Central Park attack was reported, Trump spent thousands of dollars taking out full-page advertisements in four New York newspapers in which he called for the return of the death penalty for the perpetrators of such felonies. (As it happens, the five individuals who served prison sentences for this crime were exonerated in 2002 after another man confessed.) Following the second – under-reported – attack in Brooklyn, Trump, Mayor Ed Koch and Cardinal John O’Connor, the Archbishop of New York, were all publicly accused of failing to show as much compassion to the victim as they had shown to the Central Park jogger. The charge was led by the Reverend Herbert Daughtry, a civil rights activist. There may be all sorts of reasons why Trump did not take a public stand against this crime sooner, but a seething hatred of the victim on the grounds of race and immigration status was not among them. He was deeply affronted by the accusation, and immediately arranged to visit the Jamaican woman at the Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, where she would spend a total of four months recovering from her injuries. Afterwards, he pledged to pay her medical bills. Making good on his promise, in November 1989 he sent the Rev. Daughtry a cheque for $25,000 for this purpose.

Stemming the tide of illegal or low-skilled immigration to 5America was a centrepiece of the Trump campaign in 2016, but the impetus was economic, not, as his opponents like to suggest, either xenophobic or racist.

After all, Trump’s first wife, IvanaZelníčková, to whom he was married for fifteen years and with whom he has three children, was born and raised in Czechoslovakia and only became an American citizen in 1988, more than a decade after their wedding. His current wife, MelaniaKnavs, the mother of Trump’s youngest child, Barron, was born and raised in the Socialist Republic of Slovenia and became a US citizen in 2006, the year after their marriage. She is only the second First Lady to be born outside America, the other, Louisa Adams, having lived in the White House from 1825 to 1829. Trump therefore knows about immigration at first hand just as well as anybody. Not only that, but his father, Fred, grew up in a German-speaking household having been born in New York in October 1905, three months after Trump’s grandparents moved back to America from Germany. His mother, Mary, emigrated to America from Scotland aged eighteen in 1930. That Trump is in fact a product of immigration himself is all too easily forgotten by his critics.

Trump’s focus on immigration, pushed during his first presidential campaign and the early days of his administration by his fiercely nationalistic chief strategist Steve Bannon, was all about protecting the livelihoods – and security – of American citizens. It was a response to the practical concerns of voters who know there are two types of immigration: legal and illegal. There are also two types of immigrant: law-abiding and criminal. It was illegal and criminal immigrants to which Trump devoted most of his energy between 2016 and 2020.

• • •

When President Bill Clinton delivered his State of the Union address in 1995, he received a standing ovation from Congress for his 6forceful comments on illegal immigration. Nobody seemed to mind that he referred to individuals who should not be in the country as ‘aliens’. Indeed, he used the phrases ‘illegal aliens’ or ‘criminal aliens’ four times in the space of a few seconds – language and emphasis that would trigger a chorus of righteous indignation were it to come from Trump.1 Clinton said:

All Americans, not only in the states most heavily affected but in every place in this country, are rightly disturbed by the large numbers of illegal aliens entering our country. The jobs they hold might otherwise be held by citizens or legal immigrants. The public service they use impose burdens on our taxpayers. That’s why our administration has moved aggressively to secure our borders more by hiring a record number of new border guards, by deporting twice as many criminal aliens as ever before, by cracking down on illegal hiring, by barring welfare benefits to illegal aliens. In the budget I will present to you, we will try to do more to speed the deportation of illegal aliens who are arrested for crimes, to better identify illegal aliens in the workplace as recommended by the commission headed by former Congresswoman Barbara Jordan. We are a nation of immigrants. But we are also a nation of laws. It is wrong and ultimately self-defeating for a nation of immigrants to permit the kind of abuse of our immigration laws we have seen in recent years, and we must do more to stop it.

Within a week, a Washington Post–ABC News survey gave Clinton a 54 per cent approval rating, up ten points in a month and the highest rating he had enjoyed in ten months, supporting the view that the public liked what they heard.

Across the Western world, politicians of all parties worry about immigration because of the potential impact on a country’s public services, housing stock, wages, employment and national security. The same politicians also know that acknowledging these concerns 7is crucial to connecting with taxpayers. So it is no surprise that Clinton, a Democrat, made these commitments the year before he sought re-election – and he won.

Has Trump gone much further? Not really. Of all his promises before the 2016 election, his vow to build a wall between America and Mexico attracted most attention. Covering 1,954 miles and with about 350 million crossings each year (up to 500,000 of which are said to be illegal immigrants), this border is the most frequently used in the world; yet it has long been seen by conservative Americans as the principal entry point for gangs, drugs and victims of human trafficking. Trump’s very tangible pledge to erect a huge physical barrier between the United States and its southern neighbour – and to make the Mexicans pay for it – was designed to convince voters that on this issue he would be tougher than any of his predecessors. It was a piece of political messaging genius: even the simplest of voters could understand and remember the pledge. In reality, the only real difference between what he was promising, and the border reinforcement works initiated by his predecessors was that he called it a ‘wall’ and not a ‘perimeter’ or a ‘fence’.

Barack Obama may not have made a similarly tub-thumping immigration speech during his tenure in the White House, but he did deliver a televised address to the nation in November 2014 in which he echoed Clinton’s point about the US–Mexico border, proclaiming that he had been even more robust. Obama declared that since taking office in 2008, he had deployed more agents and more technology to secure the border than at any time in America’s history. ‘Over the past six years, illegal border crossings have been cut by more than half,’ he boasted.2 He was right. Construction of a federally funded border fence began in 1993, during President George H. W. Bush’s administration, when fourteen miles were built near San Diego. Bill Clinton continued with the project during his first term. Then, in 2006, the Secure Fence Act was passed during President George W. Bush’s second administration, ultimately allowing for about 700 miles of 8additional double-layered fencing, which was completed by 2015, the year before Obama left office. Significantly, the 2006 legislation enabling the erection of this border was passed with support from three notable Democrat senators: Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden.3 None of them has ever been accused of racism for backing it.

Indeed, by the time Trump was elected, some 700 miles of border fencing was already in place. Naturally, most voters didn’t know much about the existing infrastructure, and most of those attracted to Trump’s policy just liked the sound of it. Ironically, ‘the wall’ was not even Trump’s own idea. It was cooked up as a so-called ‘mnemonic device’ – a technique used to aid memory – by political consultants Roger Stone and Sam Nunberg, to remind Trump to talk about illegal immigration on the campaign trail. No doubt they were spurred on by polls such as one conducted in 2015 for Washington Post–ABC News, which found that 65 per cent of Americans supported building a 700-mile fence along the border with Mexico and adding 20,000 border patrol agents. The same survey found that 52 per cent still wanted a wall even when told it would cost $46 billion. In other words, Trump is not a knuckle-dragging racist, as is so frequently characterised, but was instead responding – via his advisers – to public opinion.

According to Joshua Green, a CNN political analyst, the wall was Stone’s brainchild. In his 2017 bestseller Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and a Nationalist Uprising, Green revealed:

Inside Trump’s circle, the power of illegal immigration to manipulate popular sentiment was readily apparent, and his advisers brainstormed methods for keeping their boss on message. They had learned that Trump was not interested in policy detail: he preferred information and concepts to be presented in a simple, bite-sized way that voters would find easy to understand. They needed a trick, a mnemonic device. In the summer of 2014, they found one that clicked. 9

Nunberg, who worked with Stone, confirmed: ‘Roger Stone and I came up with the idea of “The Wall”, and we talked to Steve [Bannon] about it. It was to make sure [Trump] talked about immigration.’4

The scale of public enthusiasm for the wall was not that surprising. America may have been built on immigration, but even in this land of opportunity, many voters are at best conflicted about the notion of welcoming in penniless foreigners seeking the so-called American dream.

The Immigration Act of 1924, introduced after the population reached almost 112 million, limited the number of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe in favour of those from Britain and Canada, and banned all immigration from Asia, but subsequent liberalisation made America one of the most immigrant-friendly countries in the world. Over the past forty years, the official population has rocketed to an estimated 330 million. All the while illegal immigration has also thrived, most of it coming via Mexico. This legal and illegal population boom has occurred in tandem with the deindustrialisation of swathes of the country. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, one third of manufacturing jobs disappeared between 2001 and 2009. The impact of this in general terms has been that more people – both Americans and immigrants of all kinds – went in search of fewer jobs at the lower end of the pay scale at the same time, leading to a justifiable sense of apprehension among resident blue-collar workers.

The scale of the challenge was exposed in a 2017 report released by the Federation for American Immigration Reform, a non-partisan not-for-profit group that campaigns to reduce immigration. It claimed that taxpayers ‘shell out approximately $134.9 billion [annually] to cover the costs incurred by the presence of more than 12.5 million illegal aliens, and about 4.2 million citizen children of illegal aliens’.5 (It did acknowledge that illegal immigrants probably pay about $19 billion in tax – and of course calculating such costs is notoriously difficult.) The following year, a study carried out by Yale 10University suggested that the actual illegal immigrant population of America may be as high as 22.1 million.6 The very nature of illegal immigration means it is impossible for anybody to know the real numbers involved at any given time. All that is clear is that illegal immigration in America has become a significant and very costly issue – a reality that Bill and Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama and Joe Biden have all been prepared to acknowledge. Yet since Trump began talking about immigration, a gulf has opened up between the two main parties over how to approach the issue. For reasons which will become clear, it is hard to conclude that this is attributable to anything other than individuals playing politics: what Bill Clinton was able to get away with saying, Trump was not.

• • •

By the time Trump launched his presidential bid on 16 June 2015 at Trump Tower in New York, he said he had spoken to guards on the US–Mexico border. His conversations with these officials led him to conclude that ‘the US has become a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems’.

‘When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best … They’re sending people that have lots of problems,’ he went on. ‘They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.’7 Then he unveiled the policy that would become the focal point of his campaign: his promise to ‘build a great wall, and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me, and I’ll build them very inexpensively, I will build a great, great wall on our southern border. And I will have Mexico pay for that wall.’8

The commentariat was shocked. This, they predicted, would be the end of Trump’s nascent campaign. How could a serious politician get away with such inflammatory language? Washington Post writer Jonathan Capehart declared that the speech had sounded ‘the death knell’ for the Republican Party. ‘I’m going to go out on 11a limb and predict that Trump will not be the next president of the United States or even the GOP nominee,’ he wrote the following day, predicting that the candidate’s ‘harsh rhetoric’ and ‘xenophobic zingers’ he would hurl on the debate stage would hobble his efforts to secure the keys to the White House.9

In the weeks that followed, Trump’s Republican rivals for the presidential candidacy piled in. Marco Rubio, the Florida senator and son of Cuban immigrants, called the comments ‘not just offensive and inaccurate, but also divisive’.10 Jeb Bush, the former Florida governor whose wife is Mexican and who supported legalising the status of undocumented immigrants, said: ‘His remarks … do not represent the values of the Republican Party, and they do not represent my values.’11 With Trump leading Rubio in the polls by this stage, and almost neck-and-neck with Bush, it is hardly surprising that they lashed out. Of the other Republican presidential hopefuls in the nomination race during the summer of 2015, the sole fellow candidate to back Trump’s remarks was Ted Cruz, the Texas senator who, interestingly, was born to a Cuban father. He said Trump ‘speaks the truth’.

Perhaps most crucially for a businessman – especially one who was also a complete outsider to win the White House in 2016 – Trump’s hard-line stance had immediate commercial repercussions. Carlos Slim, once the richest man in the world, announced he was ending a joint venture that he and Trump had pursued in Ora TV. Univision, the largest Spanish-language network in the US, and NBC, the US media giant, said it was dropping its broadcasts of the Miss USA and Miss Universe pageants, which Trump co-owned. The department store Macy’s axed his line of suits and ties. And Nascar, the motor racing body, said it would no longer use one of his hotels for its end-of-season awards. Speaking to Fox News on 4 July, Trump said he was surprised by the strength of the backlash. ‘I knew it was going to be bad because all my life I have been told: if you are successful you don’t run for office,’ he said. ‘I didn’t know it was going to be this severe.’12 He defended his ideas, however, and 12said he had become a ‘whipping post’ for talking about immigration and crime. Even when the going got this rough, though, he stuck to his course, suggesting he did believe he could fix the immigration problem. It remains a moot point if others in the race would have made such financial sacrifices for the potential of the White House.

When Hillary Clinton’s Democrat Party published its manifesto in July 2016, it accused Trump of ‘demonising’ Mexicans and claimed, ‘He wants to build walls and keep people – including Americans – from entering the country based on their race, religion, ethnicity, and national origin.’13 The Democrats produced no hard evidence to back up this assertion. The fact that Mrs Clinton had voted for George W. Bush’s border fence a decade earlier seemed to have slipped the party’s mind. Crucially, the Democrats’ proposals also included an effective amnesty for the ‘more than 11 million people living in the shadows, without proper documentation’, who, the party said, ‘should be incorporated completely into our society through legal processes that give meaning to our national motto: E Pluribus Unum’ (‘out of many, one’). Anecdotal evidence suggests that immigrants in Western democracies are overwhelmingly more likely to vote for parties regarded as being on the left rather than on the right. Given the biggest landslide in American presidential history was only 17 million votes, it was even suggested that this amnesty was a cynical way of guaranteeing them power.14

In any case, four months later this platform was rejected at the polls when Trump defeated Clinton in an Electoral College victory, carrying thirty states and securing 304 electoral votes to Clinton’s 227. Furthermore, the House of Representatives and the Senate remained in Republican control, theoretically giving it the power of the White House as well as both chambers of Congress for the first time since 2007. Trump now had a mandate to deliver on ‘the wall’. With such numerical advantages, what could possibly go wrong when he tried to deliver the immigration policy that helped to get him to the White House? 13

• • •

Trump’s own definition of his US–Mexico border wall changed over time. On 20 May 2015, for instance, he gave an interview to the Christian Broadcasting Network in which he referred to it twice as a ‘fence’ rather than a wall. There was also significant debate before he was elected about how long it should be – or could be, given that natural terrain such as rivers and mountains along the 1,954-mile route eliminated the need for a wall covering that distance. The other crucial question was who would pay. Despite Trump’s claims, the Mexican government had made clear that it would not.

Almost as soon as he was sworn into office as the 45th President of the United States in January 2017, Trump issued a series of executive orders. They included Executive Order 13767, signed on 25 January 2017, which instructed the government to begin constructing a border wall using existing federal funding. A notice on the White House website left little doubt over where the President stood on this issue. It read:

The United States must adopt an immigration system that serves the national interest. To restore the rule of law and secure our border, President Trump is committed to constructing a border wall and ensuring the swift removal of unlawful entrants. To protect American workers, the President supports ending chain migration, eliminating the Visa Lottery, and moving the country to a merit-based entry system. These reforms will advance the safety and prosperity of all Americans while helping new citizens assimilate and flourish.15

Despite Trump’s determination, his efforts hit their own wall pretty quickly, partly thanks to Democrat stubbornness. Given that Trump had won the election on a platform of immigration control, that party’s opposition to his proposals made a nonsense of its name. 14On 11 July 2017, House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, issued a statement on the Republican Appropriations Bill to fund President Trump’s border wall, in which she referred to the wall as ‘immoral, ineffective and expensive’. A stand-off ensued, which would ultimately require Trump to find innovative ways to obtain the necessary funds to get the programme on track. In the process he would be hit by a barrage of lawsuits from states, environmental groups and border communities. The primary legal challenge surrounded the diversion of billions of dollars of military funding towards construction of the wall.

The Trump administration’s ‘family separation policy’ fanned the flames. In April 2018, the then Attorney-General Jeff Sessions announced that all adults arrested while crossing the Mexican border into America illegally would face criminal prosecution on federal charges. While they were in custody, any minor travelling with them would be placed under the supervision of the US Department of Health and Human Services. ‘If you don’t like that, then don’t smuggle children over our border,’ Sessions said.16 It may have been harsh – but nobody could claim they had not been warned. In the preceding decade, tens of thousands of child immigrants had arrived in America, with many ending up in care homes. Trump’s policy was tough, but to many American voters, it seemed a reasonable way to tackle an escalating problem that they did not consider their responsibility.

Between 19 April and 31 May 2018, according to a Department of Homeland Security spokesman, nearly 2,000 children were separated from their parents and guardians and placed into holding facilities. The scope for emotive opposition was considerable – and officials carrying out federal government’s orders sometimes played into critics’ hands. Hostility to the policy intensified when an eight-minute audio recording surfaced in June 2018, apparently of young immigrant children on the Texas border howling after being separated from their parents while a US border patrol agent made 15mocking remarks. A group of seventy-five former US attorneys wrote an open letter to Sessions calling for a rethink. Three airlines, American Airlines, United Airlines and Frontier Airlines, issued a statement asking the government not to use their planes to transport migrant children who were separated from their parents. Even Melania Trump published her thoughts on the issue, saying she ‘hates to see children separated from their families and hopes both sides of the aisle can finally come together to achieve successful immigration reform’. On 20 June 2018, Trump was forced to perform a U-turn, signing an executive order ending family separations at the border.

Multiple Western countries have faced – and continue to face – dilemmas over how to deal with illegal immigrant children, whether or not they are accompanied by adults. There are few easy answers: governments cannot afford to send out the message that anyone with youngsters will be given a free pass. The opposition to Trump’s policy was at least partly politically motivated by looming Congressional elections in November 2018. For example, the cover of Time magazine, published on 2 July 2018, showed a crying two-year-old Honduran girl, Yanela Sanchez, mocked-up next to a stern-looking Trump. Ten days later, Time was forced to issue a correction explaining that the girl had been crying while her mother was questioned but the two were never, in fact, separated. Meanwhile prominent Trump opponents, including Jon Favreau, President Obama’s speechwriter between 2009 and 2013, shared pictures of young immigrants in cages on social media. The ruse backfired spectacularly when it transpired that the images had been taken at an Arizona family detention centre in 2014 – when Barack Obama was in the White House. Evidently, in 2014 Obama’s administration had come up against exactly the same problem as Trump faced in 2018, as almost 70,000 child migrants flooded into America. The Obama administration’s response was, on occasion, to incarcerate these children – and the media did not make any fuss.

16While it may be true that there was a key difference between the way this was handled under Obama and Trump – namely that the Obama administration did not separate families as a blanket policy, as Trump’s has done – it is intriguing to note that Democrat Texas congressman Henry Cuellar told CNN in June 2018 that he had released some of the offending photos because ‘it was kept very quiet under the Obama administration’. The left-wing American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) also alleged that month that immigrant children had been physically and sexually abused while in custody. The ACLU claimed to have 30,000 pages of documents detailing the ‘monstrous’ behaviour of Obama’s border patrol force. It is a classic example of the hypocrisy Trump endured throughout his administration.

In October 2018, a growing number of illegal border crossers threatened to trigger what Kevin McAleenan, US commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, described as a ‘border security and humanitarian crisis’, as officials dealt with nearly 1,900 people per day, either presenting themselves at ports of entry without the required documents or attempting to cross the border illegally.17

Yet still Congress had failed to agree to funding ‘the wall’. So, Trump deployed 5,200 troops to the border in an attempt to contain the crisis. Matters reached a head on 21 December 2018, when the government began a partial shutdown after Republican senators failed to secure enough votes to approve the $5 billion Trump wanted for construction costs, thanks to opposition from Democrats. Bar the length of time it took to get things going again, there was nothing particularly unusual about this deadlock: the governments of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama had also shut down, putting hundreds of people who work for the executive office of the President on furlough. At thirty-five days, Trump’s hiatus was the longest in American history and showed the level of dysfunction over immigration in Washington.

In February 2019, with matters still unresolved, Trump declared a state of national emergency over the border crisis. As the Democrats, 17now in control of Congress, continued to block his funding request, it was the only way he could unlock billions of dollars to construct additional barriers on the southern border. According to the White House, up to $8.1 billion would become available in this way, from the Treasury Forfeiture Fund, the Department of Defense and a congressional spending package. Although the emergency declaration received criticism from congressional Democrats, it was not without precedent, with several of Trump’s predecessors having declared more than fifty such ‘emergencies’ between them since 1976. In November 2019, Customs and Border Protection chief Carla Provost declared that 78 miles of construction of the border wall system had been completed with 158 miles under construction and 273 miles in a ‘pre-construction’ phase. Progress continued to be made on the 30ft-high wall. Given the scale of opposition Trump faced both in Congress and among special interest groups who busied themselves filing lawsuits which certain ‘activist’ judges in America’s lower courts were happy to uphold, his determination was impressive.

On 23 June 2020, Trump visited the south-western border in San Luis, Arizona, to sign a plaque commemorating the building of the 200th-mile of new border wall. By the following month his government had obtained a total of $15 billion for the project, only 30 per cent of which was agreed by Congress. The rest came from repurposed funds from Defense Department accounts. By early October 2020, a total of 350 miles of fencing had been completed, using 524,000 tons of steel and 752,000 cubic yards of concrete, according to the US Customs and Border Protection Agency. The administration hoped to complete 450 miles of border wall by the end of 2020.

Trump’s critics have found many ways to lambast the wall, pointing out that Mexico has never directly paid for the project despite his initial insistence that it would foot the bill. Yet Trump can talk legitimately about the 15,000 troops that Mexico deployed at the 18border between 2016 and 2020 to help to stop illegal crossings. Moreover, while he had to refine his original ambition of constructing a barrier along the entire border (which he could never have done anyway because some of the land is impassable), he overcame hurdle after hurdle to complete more than 350 miles of wall.

In fact, much of this border replaced and updated existing fencing that was badly in need of repair, yet its existence acts as proof of Trump’s unwavering resolution to fulfil a campaign promise. The entire project has been estimated to cost $20 million per mile, according to a report by US Customs and Border Protection produced in January 2020 – substantially more than the 700 miles of 18ft-high fencing built by President George W. Bush, which cost an estimated $4 million per mile. But Trump’s structure is all singing and dancing, featuring floodlights, surveillance cameras and an access road.

As for how effective Trump’s border controls were, according to the United States Border Patrol there were 851,508 apprehensions of illegal immigrants in the financial year to September 2019, a 115 per cent increase from the previous year and the highest total since 2006. As impressive as this was, it is ironic to reflect on the fact that this figure fell far below the 1,643,679 apprehensions recorded in 2000 – the peak year – when Bill Clinton, a Democrat, was in power.

Either way, Trump certainly changed the debate about American immigration. In July 2020, the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan organisation, produced a lengthy piece of research entitled ‘Dismantling and Reconstructing the US Immigration System: A Catalog of Changes under the Trump Presidency’. It calculated that his administration had made ‘more than 400 policy changes on immigration’. The report concluded that Trump’s administration had had a ‘dramatic’ effect on immigration and made the first serious reforms in this area since 1996. This includes new rules making migrants ineligible for asylum if they failed to apply for it elsewhere en route to America; establishing asylum co-operation 19agreements with Central American countries allowing the United States to send asylum seekers abroad; and a new policy of making asylum seekers wait in Mexico for their adjudications, as opposed to being free to live in America. Reversing these policy changes will be a huge political challenge for any successor, so Trump’s decisions are likely to continue to have a bearing on America’s immigration system for years to come.

POSTSCRIPT

In August 2018, a 95-year-old former Nazi collaborator, JakiwPalij, who served as a guard at the Trawniki concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War, was deported from America. He had arrived in the United States in 1949 and had been a citizen since 1957 but in the 1990s it came to light that he had lied to immigration officials about his role in the war, falsely claiming to have been a farmer and factory worker. When federal authorities learned the truth about his dark past, his citizenship was revoked, and his deportation was ordered by a judge in 2004. It took fourteen years to remove him. Part of the problem was that the United States cannot criminally prosecute Second World War crimes that were carried out abroad. Additionally, perhaps unsurprisingly, no other nation was willing to allow Palij entry. Germany, Poland, Ukraine and other nations refused to take him, and so he continued living in limbo with his wife in New York, the last Nazi war crimes suspect in America. Given that thousands of Jews were slaughtered at the Trawniki camp, his presence was a running sore among New York’s Jewish community. It was Trump who made it his business to have this Nazi collaborator taken off US soil. In September 2017, all twenty-nine members of New York’s congressional delegation signed a letter urging the State Department to follow through on his deportation. After weeks of diplomatic negotiations, Palij was 20sent to Germany, where he died a few months later. At the time of his death, Richard Grenell, the US ambassador to Germany, praised President Trump’s leadership in helping to resolve the protracted legal dispute, saying: ‘I am so thankful to Donald Trump for making the case a priority. Removing the former Nazi prison guard from the US was something multiple Presidents just talked about – but President Trump made it happen.’

Not only did Trump succeed where his predecessors failed in the case of JakiwPalij, but no meaningful objections were raised to this particular hardline action against an immigrant. Whether this proves that everybody – Democrat and Republican – can agree that some immigrants are less welcome than others in America is an open question. What is more certain is that, seemingly, no other President showed as much will as Donald Trump in addressing this undoubtedly complicated case. Furthermore, it is a near certainty that none of Trump’s predecessors was as willing as he was to get their hands dirty. As America’s population continues to edge towards 350 million, perhaps future generations will be rather more appreciative of his efforts.

NOTES

1 William Jefferson Clinton, ‘State of the Union 1995 (delivered version) – 24 January 1995’, available at: http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/presidents/william-jefferson-clinton/state-of-the-union-1995-(delivered-version).php

2 ‘Full text of President Obama’s speech on immigration plan’, Reuters, 21 November 2014.

3 Annie Linskey, ‘In 2006, Democrats were saying “build that fence!”’, Boston Globe, 2017.

4 Joshua Green, Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Nationalist Uprising (New York: Penguin Books, 2017), p. 111.

5 Jill Colvin, ‘AP Fact check: Trump exaggerates cost of illegal immigration’, AP News, 5 December 2018.

6 ‘Yale study finds twice as many undocumented immigrants as previous estimates’, Yale Insights, 21 September 2018.

7 Philip Bump, ‘The toxic power of Trump’s politics’, Washington Post, 15 July 2019.

8 Glenn Kessler, ‘A history of Trump’s promises that Mexico would pay for the wall, which it refuses to do’, Washington Post, 8 January 2019.

9 Jonathan Capehart, ‘Donald Trump’s “Mexican rapist” rhetoric will keep the Republican Party out of the White House’, Washington Post, 17 June 2015.

10 Martin Pengelly, ‘“Offensive and inaccurate”: Marco Rubio rejects Donald Trump’s Mexico remarks’, The Guardian, 4 July 2015.

11 Philip Sherwell, ‘Republicans cast into turmoil as Donald Trump rides the populist surge’, Daily Telegraph, 5 July 2015.

12 Ibid.

13 Milco Baute, Democrats vs Republicans: For Whom Should We Vote? (Tampa: Baute Production Publisher, 2018), p. 92. 312

14 Walter Williams, ‘Why Dems changed course on illegal immigration’, Boston Herald, 17 January 2019.

15 Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart, Cultural Backlash and the Rise of Populism: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), p. 186.

16 ‘Attorney General Sessions delivers remarks to the Association of State Criminal Investigative Agencies 2018 spring conference’, The United States Department of Justice, 7 May 2018.

17 ‘Trump sends 5,200 troops to Mexico border as caravan advances’, Reuters, 29 October 2018.