Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

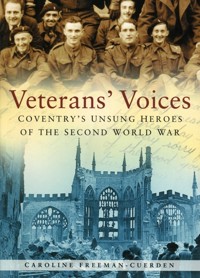

Turning the focus away from the city itself, Caroline Freeman-Cuerden has listened to the memories of 23 veterans, just a few of the thousands of Coventry men and women who served and fought in World War II. Their stories are recounted here in their own words, interspersed with letters, documents, diary excerpts and photographs.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 293

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Veterans’ Voices

Veterans’ Voices

COVENTRY’S UNSUNG HEROES OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Caroline Freeman-Cuerden

DEDICATEDTOTHEMEMORYOF CHARLIE BROWN, ARTHUR MILLS, GRACE GOLLAND, LES HAYMES, DENNIS WOOD, REG FARMER, JIM LAURIE, GORDON BATT, BENJAMIN CARLESS, ENID BARLEY, MARY ALCOCK, LES RYDER, THOMAS HORSFALL; AND CATHERINE COLLINSAND ESTHER SHAPLAND, WHOBOTHSURVIVEDTHEBLITZ.

First published in 2005 by Sutton Publishing Limited

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Caroline Freeman-Cuerden, 2005, 2013

The right of Caroline Freeman-Cuerden to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5325 2

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

PART 1:

In The Army Now

You Won’t Hear the Shell that Gets You

It Nearly Killed Us but We Were Fit as Fleas

PART 2:

In The Air

Even Better than the Birds

They Lived for the Day

That’s the Day I Should Have Died

Ordinary Chaps with a Job To Do

PART 3:

At Sea

You Can Say Goodbye when it’s Forty Below

It’s Got To Be the Navy

PART 4:

Women At War

A Few Feet Closer and We’d Have Gone Up

5,000 RAF and 80 WAAFs

Our Pauline Wouldn’t Do Anything like That

PART 5:

Normandy

They Called Them Stormtroopers

Am I in Heaven?

How Terrible War Is

PART 6:

In The Desert

The Horses Came First

Tanks Through the Minefield

PART 7:

The War With Japan

Something More than the Norm

He Died on the Spot and That’s All There Was To It

When Will We Be Out of Here?

For the Purposes of this Operation You Are Considered Expendable

They Looked like Skeletons

Cowboys and Indians

PART 8:

Prisoner Of War

There’s a Man in Here who Comes from Coventry

The Worst Three Weeks of My Life

PART 9:

Those Who Didn’t Come Back

There’s Someone Missing Here

PART 10:

The Veterans in 2005

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to James Cuerden, who interviewed some of the veterans in this book. Thanks also to Alan Roberts and Alan Hartley for the extra help they gave me in this project and to the following veterans: John Shuttleworth, Dennis Knight, Vick Wimbush, Sid Gardiner, Walter Throne, Mr A. Butcher, Ron Hadley, Les Porter, Roy Lewis, Les Ives, Joe Knatt, G. Cuddon. Thank you to Coventry’s Burma Star Association and Navy Association for putting up with James and me at their meetings on occasion, and to Evelyn Carless, Michael Carless, Linda Case, Mike Hurn, Richard Bailey, Robert Wilkinson and all the wives who have been so helpful. To those veterans who trusted me with precious photographs, logbooks and diaries (especially you, Jack Forrest) thank you so much, and lastly, thank you for your patience Alexander, Poppy and Alice.

Introduction

Bridge on the River Kwai, The Dam Busters, Pearl Harbor, we’ve all watched them. We’ve seen bullets shoot off helmets and bombs drop on homes. While Tom Hanks dodged the Germans in Saving Private Ryan, we ate our popcorn and learnt all about the horror of battle. We see war on the news all the time. We know what it’s like.

Do we? How does it feel to join up, to get the letter that tells you you’re being called up, to leave your girlfriend, your wife, for years? What was it like to lose your friends, to get hit by a mortar bomb, to see a man die, to see your first dead body, to bury one? How about when it all ended and you came home and tried to settle down? What’s it like now to live with the memories?

My aim in this book was to discover and document the stories of the men and women based in and around Coventry who served in the Second World War. Some people were reluctant to talk, others more willing; many had never recounted much of their story, even to their own family and a lot couldn’t understand why I would be interested. As one veteran said to me, ‘You know the programme Only Fools and Horses when that chap says “I remember the war”, and everyone tells him to shut up? Well, I used to feel like that.’

I spent a lot of Saturdays in Coventry Central Library sifting through old newspapers and tracing several veterans from articles printed sixty or so years ago. Sadly, when checking on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website I would discover that many of the people I was attempting to contact, particularly Coventry airmen, had been killed later in the war. Sometimes I struck lucky. I found a 1944 story of a Coventry girl who had received a medal for carrying on her duty under fire. I traced this girl who was now eighty-one and living in Wyken, Coventry.

‘Hello, is that Grace Golland? I’m sorry to bother you. You don’t know me but I’m researching a local history book on Coventry’s Second World War veterans and I found an article about you in an old 1944 newspaper. I wondered if you wouldn’t mind talking to me some time.’

‘How did you get this number?’ a very brusque voice asked me.

‘I looked up the Gollands in the phone book and by chance tracked down your sister.’

‘Well she shouldn’t have given you my number. Who are you anyway? A journalist?’

‘No, I’m not a journalist . . .’

‘A student?’

‘I’m just a mother and I’m interested in your story; I think it’s important what you did. I’ve spoken to lots of men but not many women. I don’t think your story should be forgotten.’

‘Well, I’ll have to think about it. I’ll let you know.’

About thirty minutes later Grace called me back. ‘I’ve thought about what you said, and I will talk to you.’ A few days later I sat in Grace’s living room while she searched out her medal for me from an old drawer and told me what it was like meeting the King and tracking German planes.

Some veterans wondered if they had a story at all. ‘I wasn’t a hero’ they’d say, and they’d tell me, almost apologetically, how their war was an easy one. I was told over and over, ‘it was our job, someone had to do it’.

Those who volunteered joined up for different reasons. Some were spurred into action by Coventry’s blitz, some followed a brother, a friend, for one woman it was an escape from her father; others pursued a passion for aircraft or a love of ships. Sometimes when veterans spoke to me I felt an underlying sadness hidden inside them, perhaps in the way a man raised his shoulders and breathed out a quiet sigh, a sense of loss for ambitions or dreams put to one side while men and women went to play their part in the war. ‘We gave up six years of our lives. I lost the wonderful opportunity of university.’

It seemed to me that the people I spoke to were from a generation who had to simply, in their own words, ‘just get on with it’. Many still suffer nightmares and some, more than sixty years on, wiped away tears as they remembered and spoke of lost lives. As one man said to me, ‘Nowadays counsellors talk to everybody. With us, there was no such thing.’

Among the discomfort, hardships and moments of boredom punctuated by action, there was always the comradeship. To many, coming back from war, from a life spent with mates, away from home and family, it was a tremendous adjustment to fit back into civilian life and more than a few missed the special bonds of friendship which had built up during the war years. ‘When I came out I missed the enormous brotherhood,’ one D-Day veteran told me. Another admitted, ‘It was more difficult coming back to Coventry than going into the Navy.’

Those who came back from Burma had their own, extra difficulties to contend with. As Charlie Brown, a Coventry soldier who had fought in the war with Japan, told me, ‘there were no flags or welcome. We just came home in dribs and drabs. I didn’t even have any money for my train fare. The guard at the station said if the inspector got on I’d have to get off. He did get on and I left the train. I didn’t mind. I just wanted to see my family.’

Having attended some of the meetings of the various veterans’ associations in the city and seeing the camaraderie and support among the members, I realise the great value of these groups. Associations such as the Burma Star offer veterans the chance to keep hold of that feeling of comradeship. For a few, now elderly, perhaps widowed and living alone, a monthly visit to the Navy or RAF Associations may be their only social life.

It was on 15 August that I attended such a gathering. A scattering of elderly men in smart blazers cluster outside the doorway of St Margaret’s Church in Ball Hill, Coventry. They are shaking hands, familiar faces, but fewer of them each year. These are the men of the Burma Star Association, here to mark the anniversary of the end of the war with Japan and remember their dead comrades. One of them, a Sean Connery type with silver hair and moustache, leads me in and introduces me to the vicar, Lydia. ‘We keep her in work burying us all!’ he jokes.

As the service starts the Association’s standard is marched solemnly down the aisle. Ernie Sherriff reads from the Bible, and as I look at him I think of his story and imagine him in his bomber wearing his lucky elephant badge flying above the ocean, plane swooping over sharks. I look around at other elderly men and their stories also come to mind. I picture one parachuting into the jungle, explosives strapped to his body; another waking from a nightmare, brushing non-existent snakes from his bed. We sing ‘Amazing Grace’, veterans, widows, grown-up sons and daughters all huddled together in the small chapel. The Last Post is sounded, I look across at the roll of honour, at the names of the dead carved into the Burma teak. I feel sad as I wonder if this service will even exist in ten years. The feeling of warmth and friendship is strong. The veterans care about each other, they take time to remember.

To many of us, as we busy around talking into mobile phones, dashing in and out of shops and offices, elderly men like these are just a few old blokes; what do they know about life? If we stopped to ask we would perhaps get some small insight into just what they did all those years ago. The vicar turns to me before I leave: ‘It’s an important job – documenting it all. Someone should listen.’ Here are the stories of some of them.

PART 1

IN THE ARMY NOW

You Won’t Hear the Shell that Gets You

The Story of Albert Dunn

Albert Dunn was the youngest of five sons, all of whom joined the Army. Albert was a driver for The Royal Army Service Corps and served at Dunkirk, in the Middle East and North Africa. His account focuses on his experiences at Dunkirk when he was just a young man of nineteen.

I was the youngest brother out of the lot and they really looked after me. I was always interested in warships and I wanted to join the Navy but my dad wouldn’t allow it. In 1926, when I was just six years old, he was working on a submarine, which was above the water and still in dock. For some reason or other it suddenly sank and six men were killed. My father lost his index finger. When I wanted to join the Navy he said, ‘no way. You’ll join the Army.’

So all us boys ended up in the Army. It was the first time I’d ever left them when I had to go to Dunkirk. I was a driver; I went through the whole war driving trucks, and when I came out I had to pass a driving test, would you believe, after all those years.

When we first got to France we were in one big street, trucks all lined up from one end to the other. We had different jobs to go to. I remember going to Vimy Ridge, which the Canadians had stormed in the First World War, and there were still shells sticking out of the trenches.

I had to get rid of my lorry on the way to Dunkirk, destroy it so the Germans couldn’t use it. You just pulled over to the edge of the road, put a brick on the accelerator, opened up the radiator and let the vehicle run dry. We followed behind all the evacuees; we didn’t know where we were being sent next and had no idea we would be sent home.

I stayed on the beach waiting for three nights and two days. We had no food. They were strafing the men, shelling us, planes coming over, Stuka dive-bombers coming down on us. You can imagine what we felt. I tripped up on an Army boot which was lying on the beach at one point. When I looked down at it there was a man’s foot inside. I could still cry about that. You never forget.

Albert (second on the left) and his four Army brothers. All five survived the war. (Albert Dunn)

I prayed a lot and I have to admit I did cry. People can call you a baby but you had to be there: the bombing, the shelling, ships sinking and smoking. How could you get out of it? We didn’t know what was going to happen. We’d dig ourselves into the sand dunes for cover, but you had to come out to queue up and get off the beach. We all stood in line together, officers mixed in with us waiting their turn the same as every man. There you’d be all lined up and the Germans would come, planes flying over you machine-gunning, shells exploding. You just had to run back into the dunes again. We slept in those dunes at night, dug right in, no protection or cover over us and sometimes they would shell at night. It was terrifying.

They say you won’t hear the shell that gets you. When we were making our way across the beach the shells were landing as usual. The lad next to me looked at a crater where one had just hit. ‘It never hits the same place twice,’ he said to me and he leapt in there for protection. A shell came over and landed right on top of him, blew his arm off. I’ll never forget him till my dying day. He was crying out, ‘please help me, please help me.’ I wanted to stop but some medics came up and told me to move on.

Towards the end the German planes dropped all these leaflets telling us to surrender. We didn’t bother with that. I remember one German who got shot down. His plane hit the water; you could hear the engines roaring as it went in. He parachuted out but he didn’t stand a chance. He was shot to pieces by machineguns before he hit the sea.

There were quite a few men drowned as they queued up in the water and tried to wade out to the boats. I couldn’t swim myself. You’d line up and people at the back would push forward, so you had no choice. You couldn’t do anything about it, you had to move forward and there were men went under. A lot of people were trying to bring their gear back with them too and that just wasn’t possible. I came back with nothing whatsoever, not even my tin hat.

I was lifted into the boat by these two sailors. I was absolutely exhausted, I just collapsed. They took my rifle off me, took out the bolt, threw that over one side of the boat and the rifle over the other, straight into the sea. They wanted to make more room for the men. I went back over to Dunkirk after the war and there used to be a shop that sold all the equipment, rifles and stuff that they’d picked up off the beach. I always remember when I eventually got on board HMS Golden Eagle they gave me bully beef, biscuits and hot cocoa.

There were smaller boats coming out to the ship. They had to be winched up and the men taken off. That was all too slow so we started pulling the ropes by hand to get the boats up faster. It was exhausting, we were so dead beat. The Germans started shelling the ship and we had to up-anchor and go out into deeper water. When we came back in to pick up more men all those little boats had gone and I never did know what happened to them.

When I got back to England it was to a place called Mansfield and I stayed the night at a school. The locals brought blankets and things and we slept on the floor. There was a barber over the road and he was giving all the men free haircuts. Three weeks later and I was posted somewhere else. I never got a medal for being in France because you had to be there for six months and I just missed that. I never got a medal for Dunkirk either because they said they didn’t give them for a retreat.

Paddle steamer, HMS Golden Eagle, commissioned by the Navy and the boat that took Albert back to safety from Dunkirk. (Tom Lee)

Only a few weeks after Dunkirk, Albert was posted again and spent the rest of the war in North Africa. (Albert Dunn)

The friendship in the Army was a great thing; it was the biggest thing of all really. You all got to live together and you could all die together. That’s the way we used to look at it. Dunkirk was a different experience altogether. You knew what you were going through and what all the other lads were living through. You thought to yourself, ‘well that’s it’ and you said your prayers. When I can’t sleep sometimes, even more than sixty years after Dunkirk, I think back to that time. My wife will stay up chatting to me and I’ll talk about those days and the things I saw, and I can still get upset even now I’m eighty-five.

It Nearly Killed Us but We Were Fit as Fleas

The Story of Dennis Wood

Dennis Wood joined the Army when he was seventeen, just before war was declared. He served in home defence at postings all over Britain.

My dad was in the Navy in the First World War, so listening to stories from him and his old shipmates I wanted to go to sea, the same as him. There was a two-day medical for that. I got through the first day all right but then failed on eyesight. I didn’t know I had a weak eye, I didn’t wear glasses or anything. When I got rejected by the Navy I tried the Army. I went down to Queen’s Road recruitment office; they sent me home, told me to come back nine o’clock sharp the next morning when I took the oath and was presented with the King’s shilling. I was in the Army.

I was told I was in the Royal Warwicks and I thought that’s a good local regiment, I shall be off to Budbrooke Barracks. Afraid not. They sent me to Aldershot. There were three of us from Coventry. We travelled together and when we got there we were taken to this hut and told that this would be our home until there was a sufficiency of us to make up a platoon.

This bugle sounded out and we were told this was the cookhouse call and to make our way there straightaway. We had no knives or forks, nothing at all. We were in civilian clothes and there were a lot of catcalls from all the blokes in fatigues. We were taken to this table for recruits, which was right at the far end of the dining hall, and we were shunned. It was like that meal after meal. After a few meals other recruits started to come into our hut, civilian lads like me, and after about a fortnight there was quite a collection of us. We still didn’t have anything; we couldn’t have a shave, we got a wash occasionally if we could hang out where the ablutions were and some kind squaddie would lend us his soap and his towel. That was the way we carried on. We were in a right state, not a clean shirt between us.

Eventually an orderly officer came into the hut and said there were now enough of us and to follow him to the quartermaster’s stores. We were issued with our kit at last and I ended up with a kitbag full of clothes. I had a stiff cap, highly polished peak, tunic with shiny buttons, Royal Warwicks badges on the lapel, Army boots and a swagger cane with a shiny knob on the end. After six or seven weeks more men joined, we became a platoon and then a company.

One day we were ordered to go to a certain point in the barracks. They’d rigged up these loudspeakers and they told us there was going to be an important announcement by Neville Chamberlain. It came over on the system that war had been declared with Germany. We didn’t know what it meant really. Everything felt so strange, so unreal.

After more training including eight weeks in the field, Dennis became a fully trained soldier.

We got called out as a company to help dig out this train that had been lost in the snow. It was a sub-zero winter. We got on a train at Coventry station with our pickaxes and shovels and drove out in blinding snow. Eventually the train stopped because it couldn’t go any further, there were great big drifts across the line. The order came, ‘everybody out!’ We had this little quartermaster sergeant and he jumped out and completely vanished into the snow. The snow didn’t cover the rest of us, we had our heads above it, but he just disappeared down this hole! You couldn’t move your arms, it was a hell of a game; you had to use your elbows and dig yourself up the hole to the top, lie horizontal, roll a bit, tramp the snow down and you could stand up. Everyone except this little sergeant. We felt like leaving him in there.

We marched along the line until we met this enormous wall of snow: ‘cut in there as far as you can,’ we were told. No hot drinks, no hot food, it was just a matter of getting on with it until you dropped. We were saturated and frozen, but at last we dug out the back of the train, the big buffers. We cut along to the door, opened it and there was a train load of passengers inside. They’d been stuck in there for hours. Luckily they’d had the steam heat from the engine to keep warm. We managed to unhook the last carriage with crowbars and get it moving backwards. Eventually we got the train out. It was a hell of a job for us climbing back up into our own train carriages, we were so frozen and wet we could hardly move. When we got back into Coventry they gave us a rum ration, the only time we ever had one. It was lovely and warm, just like fire.

We got called out to different things. Then one day we were issued with tropical kit and thought ‘bloody hell, we’re going out to the Far East’; then we had the lot taken off us and replaced with sub-zero kit. It was all to do with security so nobody could say where we were going. We ended up on board this big troop ship with umpteen decks. We were in the lower echelons somewhere, with no idea where we were headed. We weren’t allowed newspapers or the radio; they knew how to addle you, believe me. Eventually we could see the shadow of some land. It got lighter and as we got nearer we could make out these labourers leaning on long-handled shovels. Because of these shovels somebody said, ‘it’s bloody Ireland.’ They were right. We’d been posted to Ireland.

At one point when we were in Londonderry we got called out to the square. We were told there’d been a blitz on Coventry. All personnel from Coventry or the surrounding areas were to remain in the square and the rest were dismissed. There was a motley collection of us and we were asked if there were any slaters, tilers or bricklayers among us. I wasn’t skilled myself, but we were all given free passes to go home. They didn’t know what condition our houses were in, or whether our dependants were alive or dead; it was for us to find out.

It was a twenty-four hour journey. I came out of Coventry station and everything was normal until you got out of it. The whole geography of the city was altered. It was just a wrecked mess hidden in a fog of smoke. There were no roads, bricks all over the place, a bit of street would appear and then you’d lose it. I knew the general direction to go in and I can remember clambering over rubble in the direction of Broadgate. Stoney Stanton Road and Foleshill Road had gone. All I had to direct me was a line of poles that had carried the overhead tram wires. They’d all twisted in the heat and that was the only guide. I came to a part where there was very little bomb damage and apart from the roof our house hadn’t been touched. Some friends of ours had all been evacuated to a public air raid shelter and there’d been a direct hit on it. They were all wiped out.

We did gas training in Ireland, all to resist a German invasion. Your defence against the lung gases and nerve gases was the Army respirator and the anti-gas cape, which went right down to your boots. Unfortunately you only had to get a tear in that or a leak in your respirator and that was it. They took you through gas-filled chambers in darkness. You’d hear the swish of the tear gas and if you had a leak in your respirator you had to go round the walls, feeling your way until you found the door and then bang like mad until someone opened it. The gas used to make your neck all raw and inflamed where your respirator came round. You could hardly breathe anyway with the equipment on. You also had to fire rifles while you were gassed. The anti-smear cream on your mask was supposed to stop the lens fogging over but you still had a job to line your sights up.

Eventually the Yanks started coming over to Ireland. They were black-skinned from the southern states and they were gentlemen, they really were. They were so good-hearted, even more so than the British troops. If they found out you didn’t have a cigarette they’d throw you a carton, not just a packet. That was twenty packs of twenty and they wouldn’t take any money for it. They used the same pubs as us, went to the same dances. But then a contingent of white Americans came over and everything changed. Suddenly there was a colour bar. They segregated the pubs and it was blacks over there and whites over here. It was the first time we’d ever come across such a thing. The prices in the white pubs shot right up; that hadn’t happened before. They stayed the same in the black pubs. It was terrible because we couldn’t really afford the drinks then and just had the occasional dance to go to.

If there was any trouble it was nearly always started by the white Yanks. They’d come into a pub, go straight up to the bar, didn’t matter who was there, they’d shoulder their way through and start ordering drinks. The landlord would be all on his own and couldn’t keep up so they’d just jump over the bar and start helping themselves, that sort of thing. It was a big shock to us, we wouldn’t imagine doing that. Someone would tell the American police and they’d pull up in their Jeeps and pile in, batons drawn and they’d thrash about whacking people. They’d throw the Yankee squaddies out, literally drag them out and throw them into the Jeeps, chuck them in like a sack of potatoes. It didn’t surprise the Americans, they must have been used to that treatment back home I suppose, but it surprised us!

You were told what pubs you could use, what cinemas, right down to what side of the road to walk on. Blacks had to use one side of the road and the whites the other side. If you wanted to cross over you had to go to a special crossing point. The American police were really different to our own. If they told you to do something and you didn’t it was a bad do, no messing about.

At one point, when I’d been posted back to England, Montgomery took over, and from day one of his reign as brigadier things changed. We had cross-country runs before breakfast, no matter what the weather was like. We’d go out three weeks to a month at a time on manoeuvres; he really wanted to get us into shape. There was one exercise we did marching at night, full kit, full ammunition, attacking or being attacked. We did 125 miles on that march. Sometimes we had what they called doubling days. As soon as reveille went on the bugle call and your feet touched the ground you had to run on the spot. You had to get dressed running on the spot, you went out on a cross-country run, came back, washed yourself down as best you could and if you were spotted standing still you were on company orders. You could sit when you had your dinner but as soon as your feet touched the floor you had to run on the spot or jog, even when you washed your plate and cup, which was just done in a bucket of water thick as treacle. All day long you were jogging like that until lights out. It nearly killed us but we were fit as fleas.

After postings in defence at different locations in Britain Dennis had an accident which led to him leaving the Army.

I remember getting back to my bed and I can’t remember anything else after that. It seemed what had happened is I must have moved an item of kit and my rifle went off. The beds were the height of a man’s knee and it just blew my knee off. I can only remember small parts after that, I was drugged you see. The first bit I remember was a voice out of the haze telling me I would be all right, that I was at a casualty clearing station in Dover. God knows how long went by after that, it could have been days and nights, I don’t know. They told me they were going to fix a splint on me and that I had a long journey ahead. It ended up with a long rehab and my medical discharge from the Army. My knee is still a terrific trouble even after all these years.

PART 2

IN THE AIR

Even Better than the Birds

The Story of Gordon Batt

Ex-Bablake school boy Gordon Batt was twenty-two when war broke out. A fighter pilot during the Battle of Britain, he flew with 238 Squadron. Gordon’s life at this time was spent on alert, waiting for the call to scramble and take to the air.

I don’t think my father ever did get over me joining up, but I think he was proud of me eventually. My brother was the brainy one of the family. They used to H. get so mad at me at Bablake. Strangely enough I was never any good at school because I did the minimum to get by, but when they said to me at college, ‘if you don’t pass your ground subjects you don’t fly, you’re out’, I started working for the first time ever. My studies at the Technical College started off as night school twice a week plus homework and eventually became day release. You didn’t have much time to chase the girls round!

The worst part of a scramble was getting all these false alarms. When the phone went it was most likely change of duties, information, or ask so-and-so to go to headquarters. But then the phone would go and ‘scramble!’ Once you’d got into the aircraft, tucked your wheels up and shut the hood you felt safe because you’d got something to retaliate with. There would be a rough message to start with: Angels 15 or 20, Southampton or Portsmouth or whatever.