20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

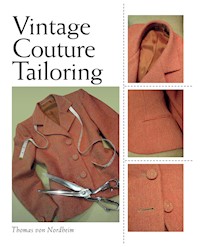

Traditional tailoring is a fascinating craft, which has not changed for many centuries, however, the techniques are now known only by a few practising in the best couture ateliers and bespoke tailor's workrooms. Nothing feels quite so luxurious or sophisticated as bespoke clothes, but the tailoring skills they require are often seen to be shrouded in mystery and the clothes therefore only accessible to the rich and famous. This practical book reveals the trade secrets of couture tailoring and brings vintage couture tailoring within the reach of all. With step-by-step photographs and professional tips throughout, it shows how a ladies' jacket is made and thereby introduces a range of fundamental tailoring techniques. These can be used for garments for either gender, as well as other sewing projects: moulding fabric to shape with the iron; employing loose interfacings; hollow shoulder construction; pad stitching canvas; interlining and weighting hems;making tailored and bound buttonholes;.... and many more forgotten techniques.Written by a tailor of international repute, Vintage Couture Tailoring is dedicated to all who appreciate the highest standard of craftsmanship, and who like using their eyes and hands to produce beautiful garments.Vintage couture tailoring is practised by only a few establishments around the world today and this practical book reveals the trade secrets of couture tailoring. An invaluable guide for professionals wishing to further their skills, and for enthusiasts with an interest in traditional tailoring. Shows how to make a ladies' jacket from preparation through to assembly and reveals the exquisite finishing details that are the hallmark of couture tailoring. Superbly illustrated with 417 colour step-by-step photographs.Thomas von Nordheim is a tailor of international repute.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Vintage Couture Tailoring

Thomas von Nordheim

Copyright

First published in 2012 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This impression 2012

This e-book first published in 2013

© Thomas von Nordheim 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 588 1

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the memory of Mrs Lore Lang, at whose Haute Couture Salon in Düsseldorf, Germany, I did my apprenticeship between 1989 and 1991. She died aged 82 in March 2011. I will always remember Lore Lang as a strong character, a very chic woman, and an uncompromising perfectionist as far as craftsmanship and the running of her business were concerned.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

01 A brief history of tailoring

02 The tailoring process

03 Tools of the trade

04 Preparations, cutting and marking

05The use of interlinings

06Creating and supporting shape

07Building the jacket fronts

08The jetted pocket

09The tailored collar

10 The tailored sleeve

11 Lining the jacket

12 Buttonholes

List of suppliers

Bibliography

Index

Other craft technique books from Crowood

Preface

We live in an age in which fashion and clothing have become casual, fast-lived consumables. For many people the number of items in their wardrobe and how often they change them is more important than their quality and longevity. Because of that, clothes no longer need to be made to last.

This has not always been so. Even fifty or sixty years ago clothes used to be purchased only every so often and even when bought off the peg, they were constructed to last and were handed down, remodelled, mended, and cherished. The craft of tailoring was well regarded and most towns had their tailors and dressmakers, frequented even by people of limited means. National UK statistics of the 1930s indicate that every other man in the population had a suit made every two years. It is likely that women called upon their tailors even more often, to have their ‘costumes’ made (as suits were called back then). In addition most women knew how to sew; if they had not learned sewing at school they would have been taught by their mothers and often showed considerable skill in manufacturing dresses and basic tailoring for themselves, as well as clothing their children.

With the disappearance of handicrafts (most of them in fact), whether due to technical advances in manufacturing, rising costs of labour and cheap competition from the East, or changes in attitude – most likely a combination of all of these – a good deal of culture and its associated base of skilled artisans have vanished from our lives. Apprenticeships have mostly disappeared, aside from the fact that most young people nowadays aim to pursue a career after going to university, rather than learning a trade; even some MA fashion design students lack very basic construction skills. Yet it requires modellers, pattern cutters, fitters, tailors, dressmakers, machinists and hand finishers to put designers’ visions into reality. The question is how long it will be before there are only a few people left who will be able to pass on their knowledge. Already there is a shortage of experienced technicians at colleges and the remaining bespoke tailors complain of having difficulty in hiring highly skilled staff.

In recent years the trend has returned towards handcrafted products, mostly textiles-based accessories, but also niche market clothing with a twist on something – for example reconstructed vintage or garments made from ecologically sourced fabrics with a particular provenance. A new generation of environmentally conscious middle-class consumers is looking for customized, well-made but quirky clothes with individuality. They are tired with what they can find in the high street or in expensive designer boutiques. This must be a welcome trend, but has little to do with craftsmanship or indeed couture.

In these modern times, a few couture houses are surviving like dinosaurs and cater for this already rare species, the typical couture client: mature, discerning, used to the best of everything, knowledgeable about quality and fit, able and prepared to pay. In their view the expense of having clothes made is well worth it: many upper-class people wear their bespoke clothes until they literally fall apart, having got more than their money’s worth out of them. The garments have lasted well in the first place because of their superior materials and construction. Moreover, their classic style remained fresh over many years. Ultimately this means fewer clothes, but of better quality. Even peoplewith lesser means shouldlearn from this attitude; couture clothes are often seen as a luxury, but are actually worth every penny. Truly extravagant are those people who consume cheap, high-fashion items and discard them after wearing a few times. Historically, couture has always done well in times of recession, showing that even in times like this, those who prefer flawless craftsmanship and no-nonsense styles will not accept second best. They would rather buy one or two fewer outfits a year, but stillcommission investment pieces.

Couture is not about sketching pretty clothes and entertaining glamorous clients. Making bespoke clothes is hard work and this should be considered if you are thinking of using your skills professionally. Fashions aside, you need to be able to customize designs and have an aesthetic feel for colours, fabrics and textures, as well as an understanding of what suits different figures. Next comes the cutting, a profession in itself, and there are also many different technical skills in garment manufacture. Fitting is another most important skill, as every client’s figure is different – couture clients used to consider their fitters more important than the designers, and would follow them to other houses. Lastly you have to have the necessary skills to run the business side: there will be frantic periods and those with no orders at all. This advice is not intended to discourage, but it is important to learn to walk before you run. Every piece has a soul: the cut and shape, colour and texture are as individual as the style and personality of the customer who is going to wear it!

Many people have taken up sewing as a hobby again, as proven by increased sales of sewing machines in recent years, and this is an encouraging development. As opposed to paying a lot for having their clothes made, those who actually work the couture way are investing a good deal of time and effort in their work. They will come to appreciate the amount of labour and skill that goes into the manufacture of bespoke garments. Needless to say they can choose what really suits and flatters their physique and can creatively customize their wardrobes by building up useful unique pieces. There is of course the added satisfaction of achievement, having made something yourself which you can wear with pride.

Although an advanced skill, traditional handcraft tailoring in its pure form is the base for all other sewing. A tailor can make a dress, but a dressmaker cannot make a tailored jacket. Most stitches in tailoring encompass those used in other needlecrafts, including millinery. This book will explain step by step how to build a jacket from scratch. It is a ladies’ jacket tailored the men’s way, but the techniques can be utilized in the manufacture of garments for either gender. The cut, governed by style and the female anatomy, as well as some minor finishing details (most of which are invisible from the outside) would differentiate the jackets. Learning how to make a tailored jacket includes fundamental skills and techniques that will be useful for all your other sewing projects. Whether you are a professional wishing to refresh or deepen your knowledge or a sewer wanting to explore tailoring, this book is dedicated to all those who appreciate quality and craftsmanship and wish to know more about the trade secrets that hide behind the mystique of old-school couture tailoring.

Author’s remake of a 1951 Balmain suit.

Chapter 1

A brief history of tailoring

The two-piece suit is nowadays the internationally accepted apparel, but few know the origins of these garments. The collar and lapel of modern tailoring (formerly worn up at times as a means of protection against the elements), as well as details such as the buttoned cuffs (also referred to as ‘surgeon’s cuffs’, indicating they can be unbuttoned to allow rolling up the sleeves to engage in ‘dirty’ work) and vents in the back of a jacket (so the wearer can sit comfortably on a horse), are not thought about much and are commonly seen as ‘classic design’ from which even cutting-edge designers cannot get away. They have no utilitarian function as they did 200 years ago, so really they are decorative anachronisms.

Tailoring is a very old craft and was already regulated by Guilds during the Middle Ages in Europe. The origins of tailoring are supposed to be rooted in the structures made by stitching together material and wadding (pad stitched as we still use it now), to be worn under armour so that the body was protected against the heavy metal casings.

Retaining the stiffness of armour, but no longer a functional feature, in the late Middle Ages and during the Spanish fashion of the Renaissance period heavily padded clothes were worn: rigid fabrics, cod pieces, extreme shoulder puffs and peascod belly doublets. This created extravagant fashion silhouettes, which did not resemble the human shape underneath but represented the status and wealth of the wearer in their geometric formality.

After the unrest of the Thirty Years’ War in the early seventeenth century, clothes became less structured. The loose-fitting buttoned coat with narrow, sloping shoulders (worn with casual nonchalance) was the most popular men’s garment. Over the century and during the next, they became increasingly formal again and elaborate rows of decorative buttoning and rich embroideries adorned the fabrics. Coat skirts became fuller and were executed in stiff silks and velvets. Worn with a waistcoat and breeches, this was the prototype for the modern men’s three-piece suit, although each garment was made from different materials and the collar did not exist as such by then.

In the late eighteenth century, fashion looked to England, where country gentlemen wore informal woollen frock coats with collar and lapel. This was the start of a swing towards more casual and comfortable clothing again, which was to impress with proportion and fit, rather than ostentatious surface decoration. Around 1810 English tailors cut the coat with a waist seam, which allowed the garment to be more fitted. This cut was used on men’s coats throughout the nineteenth century, into the early 1920s on suit jackets, and is still in use today on morning coats and tail coats, the two most formal pieces of men’s clothing to have survived. At this time wool fabric replaced the stiff, rich fabrics of earlier times. With the help of discreet padding, clever cutting and tailoring techniques (the malleable wool fabrics reacted to heat and steam), a new sartorial ideal was invented. Tailoring firms like Stultz in London’s Savile Row or Staub in Paris’s Rue de Richelieu founded the reputation for these still flourishing world-class tailoring centres.

Pattern cutting systems, complicated apparatus for measuring, and the inch tape itself, were invented. Prior to that, strips of paper with notches were used to keep a record of customers’ measurements, but there were no templates. Customers had to supply their own material purchased at a draper’s shop and then each garment was cut by guessing and altered by the tailor with more or less skill, a lengthy process involving many fittings.

As a rule, garments were made to order; however, a few tailors started selling made-up garments in the late eighteenth century. The appearance of the straight-cut long overcoat in the 1840s meant that this type of unfitted garment could be made in advance and more merchant tailors offered these off the rack. Technical innovations of the Industrial Revolution meant goods could be acquired more cheaply and there was more demand for formal clothing from an increasingly ambitious and wealthier middle class. It has to be remembered that at this point the sewing machine had not been invented and all clothing, bespoke or confection (ready-made clothing), was entirely hand sewn. When it did arrive in the 1850s, it was not frequently utilized. A hundred years on from then, many ready-to-wear tailored garments were still hand finished, including buttonholes and lining around the armholes.

Throughout the nineteenth century, tailored garments were stiffened with various starched linen canvases, stiff buckram, even cardboard; padding was made from horsehair matting, cotton wadding or kapok (all of which are still used in traditional upholstery, a related craft). Coats were tight-fitting, achieved through multiple seaming in the coat. Around 1850 the coat was cut short to what we now know as a jacket. This was in response to increased demand from men to wear more comfortable clothes for leisure and sports. The buttoned sleeve cuff allowed workmen, doctors and so on to turn up their sleeves when needed.

Men’s fashions.

In the mid-nineteenth century it was not yet fashionable to wear coat, waistcoat and trousers made from the same material – quite the opposite. The three-piece lounge suit made en suite, resembling the modern business suit, arrived in c. 1870 and became the most popular men’s apparel. It was, however, considered distinctly lower class and was only worn for country pursuits and travelling by higher members of society. The frock coat and the semi-formal morning coat, still worn with contrasting trousers, were worn by upper-middle-class businessmen, politicians, bankers and doctors. Considered old-fashioned by then, they disappeared entirely from general wear between the two world wars. As with all old-fashioned dress styles, they either vanish or live on as a kind of costume reserved for special formal occasions (white tie for banquets, morning coat for weddings, events at court, and so on); alternatively they become a dress style reserved for servants (very grand staff wore eighteenth-century style liveries well into the mid-twentieth century, including wigs). Even today, waiters still wear black tie in some establishments.

Throughout the nineteenth century, coat styles changed with fashions, but this was limited to the style, length and width of lapel, trimmings, pockets, quarter details, etc. The jacket shape was basically an unshaped straight-cut garment to cover the natural human body without exaggeration. Towards the end of that century, jackets were fitted more closely to the body. Just after the First World War and until the early 1920s, jackets had heavily padded fronts with stiff built-out chests (referred to as bombé in French), although this was due to the poor quality of materials available at the time. From the late 1920s, jackets were very fitted and had wide and straight padded shoulders – a look that would last throughout the 1930s. Attributed to a London tailor called Scholte, a new cut called the ‘drape cut’ (also known as ‘London cut’) was introduced. By widening and padding the shoulders and cutting the chest with extra cloth so it draped before the armhole, the figure seemed to have the fuller chest of an athletic person. This cut is still used by some establishments today.

Horsehair canvas had been made since before the First World War, but only became popular as body interfacing, rather than just for chest re-inforcement, in the 1930s. More tailors accepted that the superior springy quality of hair canvas led to an improvement in the construction of jackets, replacing the previous layering of limp linen. By this time suit jackets never had vents in the back, whether single or double; this only applied to riding jackets. Generally, single-breasted styles were considered less formal than double-breasted, but before the war, were acceptable when worked with peak lapels (when the revers goes into an upward point).

After the Second World War the American V-silhouette, with its extremely wide, padded shoulders and long, straight, oversized cut, became the fashion. In 1950 a neo-Edwardian style was propagated by London tailors, and taken on by the Italians, who became ever more prominent as fashion trendsetters in the 1950s. Jackets with wide but rounded shoulders, short lapels and only slightly fitted at the waist, were the look. From the mid 1960s jackets were cut closer to the body again and in the early 1970s very tight-fitted jackets with narrow but high padded shoulders and very wide lapels became the fashion. This was an exaggerated ‘retro’ take on the 1930s, and was followed by a more relaxed fit, but still cut quite closely to the figure. Oversize styles with ridiculously wide padded shoulders for both sexes were the fashion from the mid 1980s.

Traditionally only men did tailoring (‘man-tailored’); they also fashioned ladies’ corsets and riding habits. Though professional seamstresses were employed to do trimming and hand-finishing, they never designed, cut or fitted garments. In the eighteenth century this changed: dressmakers set up businesses and formed their own guilds. It was here that the differences in craftsmanship in traditional gents’ and ladies’ tailoring began.

Ladies’ tailoring

When it became fashionable for women in the last quarter of the nineteenth century to wear crisply tailored suits in nautical, equestrian or military styles, men’s tailors again were sought after for their high standards of exquisite craftsmanship. At this time many prestigious businesses renowned for their ladies’ tailoring such as Redfern (with branches in London, Paris and later New York and Edinburgh) were established and houses such as Henry Creed (est. 1760) rose to fame.

Around 1870 ladies began to wear so-called ‘tailor-mades’, meaning a shirt and jacket worked from the same material. They existed alongside ‘faux suits’, where the jacket was joined to the skirt. Suits, later called tailleurs, then known as ‘costume’, were considered to be distinct street wear and featured collar and lapels like men’s suits. The sleeves usually had cuff details rather than buttoned vents. All jackets were extremely closely fitted over the corseted figure, shaped by means of multiple seamed panels and sometimes boned so as to lie flat. Sleeves were always tight, except in the late 1890s when huge leg-of-mutton sleeves were fashionable. Always fashionable was the cut-away style.

In the last half of the 1910s short bolero-type jackets and loose-fitting longer jackets were worn. After the First World War Chanel presented unstructured suit jackets, something for which she later became world famous. (Then, as now, a Chanel jacket had no interfacings.) With the un-waisted 1920s fashions came the straight cut, often collarless jackets and coat. Sleeves were now straight and comfortable. Crêpes and jerseys were used as materials and this added to the soft, ‘dressmaker’ look, which lasted through to the late 1930s.

Ladies’ jackets and coats then became more structured and fitted again; the styling (collar and lapels) as well as the fabrics resembled the men’s jacket and has done ever since. Although tailored trousers were already worn by some women in the 1930s – Marlene Dietrich famously had her suits made by gents’ tailors, including Savile Row’s Anderson & Shepperd – this was the exception and seen as film-star eccentricity. Trousers were reserved for beachwear.

Ladies’ fashions.

The mid 1930s can be seen as the birth of what is considered now ‘the classic suit’, both for men and women. In London, Digby Morten, then designer at Lachasse, popularized masculine tweeds and made these fabrics acceptable for any time of the day, as well as for town wear, quite a novelty then. From 1938, jacket shoulders became wider and heavily padded, a uniform-like look that did not change throughout the wartime period.

Dior’s ‘New Look’, presented in 1947, epitomized a tendency towards more feminine styling after the war: with its rounded shoulders, defined bust and small waists, and fuller and longer skirts, it was the opposite of what had been the fashion. However, this look took a while to filter through and most suit jackets and coats remained wide and square-shouldered through to the early 1950s, often more exaggerated than the men’s jackets.

In the 1950s Dior imposed new fashion lines every season. Suit jackets ranged from very fitted with tight waists and extremely rounded, padded hips and stiffened basques, to semi-fitted and loose styles. Master tailor Balenciaga presented a short coat that was fitted in the front, but had a wide swing back. The couture tailoring of the 1950s, with its incomparable array of architectural styles and structured details such as collars, fly-away cuffs and so on, required a return to stiff interfacings as well as padding and even boning. As a direct contrast, in 1954 Chanel re-launched her famous unstructured soft suit. A trend for sleeves cut in one with the front and back of the jacket, as opposed to the traditional set-in sleeves, became very popular for the next decade or so. Many women still went to their local dressmakers or made clothes themselves at that time, however.

From the mid 1960s, women also wore trouser suits as an alternative to skirt suits, a trend lasting well into the 1980s. The ‘ready-to-wear’ industry really took off and this is where the decline in handcrafted clothes started.

The 1970s saw tight-fitting masculine jackets, often with the fashionable ‘pagoda’ shoulder. The 1980s saw a decline in the wearing of suits and gave way to co-ordinates, separates and ensembles. The look was, as in men’s fashion, oversized with wide, padded shoulders.

In the 1990s, tailoring became less popular, but it has returned to the fashion scene with the adoption of 1960s/1970s retro styles in the early twenty-first century.

Whilst all these fashion phases are coming and going, classic tailoring has really never been away. Women have always had the tailored jacket, which, combined with a matching skirt to make up a formal suit, with trousers for semi-formal or business wear, or dressed down and combined with jeans, has remained the staple backbone of many wardrobes for decades, whether bespoke or high street.

Gents’ tailoring has always been executed by craftsmen, often without acknowledging any fashion influences; indeed, some establishments distinctly refuse to take notice of clients’ wishes, even if they ask for a more adventurous cut. This makes dating men’s clothing somewhat more difficult than women’s, but the styles can often be distinguished by details in cut or by the materials and trimmings used.

For example, a beautiful, almost unworn overcoat from navy herringbone wool and cashmere complete with velvet collar and silk lining was bought in a second-hand shop a few years ago by the author. It was a timeless classic that style-wise could have been anything from 1900 onwards, but its immaculate condition suggested that it was made more recently. On examining the inside pocket, where tailors put their label with the client’s name and date of manufacture, it was discovered that the coat had been made in 1968, making the coat the same age as the author!

The jacket front ready for mounting to canvas.

Chapter 2

The tailoring process

Many sewers will have considerable experience in dressmaking and even tailoring. This is undoubtedly an advantage, but you may wish to re-consider some of your techniques and take from this book what works best for you. The reasons behind doing things a certain way will be explained at each stage, making the processes easier to remember; they will soon become a habit. A thorough training in tailoring involves doing most things by hand in the traditional way – whilst using a stock cube in cooking is just fine, to know how to make proper stock from scratch is a different matter altogether! Amongst all the different designers and houses there are many ways of doing things, and only individual circumstances can justify the preference of one technique over the other. Once you know how to do things properly and understand the reasons behind the various techniques, you will be able to judge when cutting a corner is acceptable.

Fitting stages

Garment construction in ladies’ couture and gents’ bespoke tailoring goes in stages, usually with three fittings. These will differ slightly from establishment to establishment.

The first fitting

The first fitting is completely hand-basted only. Some gents’ tailors call this ‘skeleton baste’. All sections are cut with larger inlays and hems so as to allow for alterations such as displacing seams or ‘crookening’ (changing the balance) the shoulder or back. Even if you have kept a copy of a customer’s pattern, the fit might have to be adjusted differently every time, because every cloth behaves differently. All seams and darts are tailor tacked and basted together. Then the seams and hems are tacked flat so they appear pressed. The garment sections might be ironed to shape and shoulder pads are inserted. The jacket fronts are mounted on canvas so that it supports the shell fabric. The first fitting has no sleeves and no collar. The sleeve is pinned on so as to establish the correct pitch and length. The collar, cut in canvas only, is pinned to the neckline and the lapel width and collar notch are established. The pocket positions are established with a piece of canvas, or may be just marked with chalk.

Each tailor has a different way of indicating necessary alterations by putting pins in a certain code and pattern on the garment. After the fitting these pins are thread marked, usually in a coloured thread. (In continental couture houses the superstition is never to use green thread for this, as it is unlucky.) The flat basting is opened, the canvas removed and any alterations are carried out to the seam lines, according to the pin marks the fitter has placed. The sleeve is taken out, but not before balance marks have been carefully made to indicate the armhole and sleeve head shape as well as the pitch.

The second fitting

For the second fitting usually the seams and darts are machined and pressed. The lapels are pad stitched and an under collar padded and tacked to the neckline. The outer edge of the jacket might not be final, so finishing the edge with stay tape is not yet carried out. Pocket flaps, welts or patch pockets are prepared and basted in place. The hems and outer edge are tacked flat again and the machined but not finished sleeve is basted into the armholes.

Some tailors will finish pockets and even put facings as well as the top collar on for this fitting.

After the second fitting the alterations are again marked with thread, but this time in a different colour for reference.

The third fitting

For this (usually final) fitting the pockets are made, the facings and top collar are put on and the lined and finished sleeve is basted into the armhole. The jacket is still not lined, although some gents’ tailors line the back for the second fitting. Buttonholes can be made at this point, but it is not unusual to leave this until the very end. After this fitting the jacket gets finished, ready to be dispatched or collected by the customer.

Sequence of work

This book is not written in the absolute sequence of how a tailor would work; for example, making a hem is explained in the section on interlining. Two ways of applying buttonholes to a garment are also explained, but these need to be made at different stages of construction.

Below is a list of the usual sequence of work in the construction of a jacket. The fitting stages have been omitted. For ease of reference, the page number for each stage of construction is given.

Preshrink cloth (page 30)Establish side and direction of cloth (page 29)Cut out the garment (page 31)Mark the garment with tailor tacks (pages 32-35)Pre-shrink canvas (page 40)Cut out and construct the canvas (pages 40-46)Execute dart and join the side panel onto jacket front (pages 67-69)Mount jacket fronts to the canvas construction (pages 69-73)Pad stitch lapels (pages 73-75)Stay the edges and break line (pages 75-79)Apply bound buttonholes (if applicable) (page 145)Apply pockets (pages 91-97)Apply the revers facings (pages 79-89)Open the back of bound buttonholes (if applicable) (page 150)Join the back to the fronts (page 87)Interline and make the hem (to include vents if applicable) (page 47)Execute the shoulder seam (page 89)Make and apply the collar (pages 99-107)Execute the gorge seam (pages 106-108)Make and insert the sleeve (pages 111-121)Apply shoulder pads (and all other padding if applicable) (page 122)Make and apply the lining (page 125)Apply tailored buttonholes (if applicable) (pages 139-145)Sew on buttons (page 145)Garment terminology.

Terminology

The diagram shows the terminology for the garment sections as used in this book.

01/ Armhole or scye: where the tailored sleeve gets sewn in.

02/ Sleeve cuff: the bottom part of the sleeve; this can be vented, plain or cuffed (turned over), or have a separate cuff.

03/ Inside facing: the section of the facing on the inside of the jacket front, as opposed to the visible part on the revers.

04/ Lapel or revers: the section of the jacket front that folds back.

05/ Collar stand: the collar stand is the part not visible from the outside as it is hidden by the collar fall.

06/ Collar fall: the section that folds on the collar break line and comes over to the outside.

07/ Collar notch: the gap between collar and lapel. In a peak lapel the lapel continues and forms a point beyond the collar point.

08/ Gorge seam: where the revers facing joins the top collar.

09/ Quarters: the lower front sections of the jacket fronts. This can be square, rounded off, cut away or otherwise shaped.

10/ Sleeve head or sleeve crown: the top part of the sleeve which is set into the armhole with ease. This can be flat, high, round, square, roped, gathered, pleated or darted depending on the style.

11/ Break line: where the lapels turn over. This is never pressed flat, but should gently roll.

12/ Break point: the point at which the lapels roll. This is where the buttoning starts.

13/ Dart: fabric sewn away from the back to create suppression.

14/ Neckline: the point onto which the collar joins (can also be bagged out in collarless styles).

15/ Bust point: natural bust point, usually but not always the end of the front dart.

16/ Centre front line: where the two jacket sides meet exactly on top of each other; over- and underlapping are referred to as wrap and button stand respectively.

17/ Front panel or foreparts: the whole garment front.

18/ Side panel: the side garment section, often several pieces rather than one.

19/ Lining: separately made-up material to cover the insides of the jacket.

Terminology

Canvas: refers to the interfacing construction in the jacket front, even if other material has been employed.Interfacing: material to stiffen and give support to the jacket. This can be the canvas or a mounting material.Staying: keeping fabric from stretching where it is off grain, with stay tape, bridles or straight cut fabric.Easing: making fabric shorter in sections by shrinking or gathering it.Padding: stitching two or more materials together with pad stitches; also supporting shape by stuffing garment parts (such as shoulders or sleeve heads) or as in balancing padding.Hem: bottom edge of the garment or sleeve; also extra amount of fabric on the inside of the hem.Seam allowance, inlay: extra amount of material on the inside of a seam.Threads

You can buy threads made from various fibres: polyester, cotton and silk. In ladies’ tailoring, silk thread is generally used by fine tailors, even when working with wool. Seams stitched with silk will not break, due to silk’s natural elasticity, and will meld into the fabric. It is easy to work with for both machine and hand sewing.

In gents’ tailoring, cotton thread is traditionally used. This is somewhat hard, but stronger and well lasting. High quality polyester thread can be acceptable for stitching, but not for very light fabrics as it very sharp.

For general hand and machine sewing, use thread with a thickness of Nm100 (the number should be displayed on the reel). The number indicates the number of metres of thread that is 1 gram in weight; therefore the higher the number, the finer the thread. The only other thread used in tailoring is buttonhole thread, which can be obtained in silk on 10 metre reels or polyester in 50 metre reels. The choice of colours is somewhat limited. Buttonhole thread has a thickness of about Nm40 and is used to make buttonholes, for stitching on buttons, hooks, eyes, etc, and for decorative top stitching. In gents’ tailoring, linen thread is often used for sewing on buttons.

Hand stitching techniques

There follows a list of the stitches you will need to master when following the construction process as presented in this book. Some will be familiar; some might be new. If you are right-handed, all hand seams are carried out from the right to the left side or towards you if you angle the work. The only exception is the cross- or herringbone stitch, which is executed from left to right. If you are left handed the opposite applies.

A seam joins two or more layers of fabric and may perform the following functions: temporary joining of materials (as in basting); control of fullness; protective, so as to prevent fabric from fraying; permanent joining of materials; and for decorative purposes.

When a material joins another material, it can either be a raw or folded edge. Joining two raw edges is possible in very thick materials (this is called ‘stoating’), but more commonly one raw edge gets joined to another material, for example a men’s under collar joined to the neckline. In some of the illustrations, the stitching has been executed in thick silk thread, often in a contrasting colour, so that it shows up better. In general, all stitching is done with a single strand of thread (the only exceptions are tailor tacking and easing the back armhole with a chain stitch, both of which are done with double basting cotton). All hand seams start with a tailor’s knot unless otherwise mentioned.

Running stitch.

Running stitch

The running stitch is the most basic of stitches. It is used for basting seams; to temporarily control fullness, such as in gathering the sleeve head; to make tailor tacks; and to hold together layers of material permanently where the stitching is not visible, for example holding together canvas and shell fabric around the armhole.

Fell- or slip stitch.

Fell or slip stitch

Felling is used to attach a folded edge to a flat surface invisibly, such as stitching lining in place or attaching the edge of the stay tape. Slip stitching can also join two folded edges invisibly, such as on the facing hem (two folded edges on top of each other) or on the gorge seam (two folded edges against each other).

Sink stitch.

Sink or prick stitch

This stitch invisibly joins fabrics together, usually done through the ditch of a seam, for example on the bound buttonhole or jets of a pocket. If it does not go through a seam, such as on a gents’ jacket edge, little pricks will show. The thread should not be pulled too tight as this results in dimples.

Padding stitch

Padding stitch

The padding stitch is used to join two or more layers of fabric together. The stitch is only visible on the side where it has been executed. It is used for the lapels and the collar and to fix interfacing (such as on the hem) in place. As it is done diagonally, it is quite an elastic stitch. It can also be used to baste cloth in place temporarily, for example the revers facing or top collar. Padding stitch will form the characteristic herringbone pattern.

Cross stitch.

Cross or herringbone stitch

The cross stitch holds a raw edge securely against a flat surface, for example when stitching the bust dart in the canvas or to hold a seam allowance or pocket bag down. It can also be used as a strong hem stitch.

Whip stitch.

Whip stitch

The whip stitch overcasts a raw edge to keep it from fraying, such as the tailored buttonhole or a seam allowance. It can also join a raw edge to a flat surface such as the stay tape to the canvas, seam allowances on the jacket edge, or the raw edge of the facing to the interfacing.

Whip stitch variation.

A variation of the whip stitch is shown here. Instead of inserting the needle a little further on from where the needle comes out on the raw edge, resulting in the visible part of the stitch being slanted, the thread is pulled straight across at a right angle and re-inserted there. In a way it is a felling stitch with part of the thread visible. This stitch is used to stitch on a gents’ undercollar.

Blind hem stitch.

Blind hem stitch

This stitch joins two layers so as to be invisible from either side of the fabrics between which it has been executed. It is mainly used for hemming, as the name suggests.

Back stitch.

Back stitch

The back stitch is a very strong, yet elastic stitch and is used in tailoring to sew sleeves into the armhole or for the crotch seam on trousers. It is also used as a temporary basting stitch, for example on the collar and lapels, to keep several layers from shifting during pressing.

Chain stitch.

Chain stitch

This is the same as the embroidery chain stitch, except in tailoring the stitches are pulled tight. Each stitch locks fullness, as opposed to gathering where you are able to move the fullness about. The chain stitch is done with double thread.

Feather stitch.

Feather or baseball stitch

This stitch butts up two folded edges temporarily such as on the jetted pocket. It keeps the two edges from overlapping and shifting. It used to be used for joining canvas panels that had been cut to shape.

Buttonhole stitch.

Buttonhole stitch

The buttonhole stitch is made in thick silk thread to oversew the cut edge of a buttonhole opening. It is a very durable stitch as with every stitch you knot the thread. It can also be used to sew on hooks, bars, eyes and to make thread bars, swing catches and so on.

The tailor’s dummy and tape measure.

Chapter 3

Tools of the trade

As with any craft, it is of paramount importance to have tools of the best quality you can afford. This is certainly true for tailoring. Although some tools need only to be basic to achieve good results, some are now so specialized that they are very difficult to obtain, and have to be sourced from countries such as Switzerland, Italy and Germany. It is possible to source some of these tools from vintage junk shops, auction sites and the like, but there are also some home-made alternatives, as explained below.

Tools can be categorized as follows: sewing, cutting, pressing, measuring and drawing tools.

Sewing

Sewing machines

People ask, ‘Why is it called ‘hand-craft’ tailoring, if you use a sewing machine?’ You may be surprised to learn that of the thousand or so stitches that go into the making of a tailored garment during its construction, only a fraction are permanent, and only a small proportion of those are executed by machine. Bespoke tailoring is a process in which a garment is assembled by hand for fittings and then taken apart again numerous times until all seams are permanently stitched, by hand and machine. All of the tailor tacks and bastings are temporary. Seam lines are marked, seams are basted together, then basted flat to look as though they have been machined and flattened with the iron. All of the edges get basted flat before they are permanently pressed with the iron; and all seams get basted first before being stitched by machine, so that the fullness stays in the right place and the fabric cannot shift. The long seams of a garment are machine stitched, as are the pockets and anything that is bagged out, like facings. Sleeves are also stitched in by machine; however, some old-fashioned tailors prefer to sew those in by hand. Depending on the type, a hand seam can be stronger than a machine one. A back stitch where the thread is not pulled too tightly is very strong, yet has some elasticity, which is required in seams that are under great stress (crotch seams in trousers for example, which are also often done by hand). Modern high-end tailoring production uses machines that pad stitch lapels and collars, blind stitch the stay tapes, bridle and hems, imitating the hand stitching of bespoke tailoring. There are also specialized machines that prick or saddle stitch along the edges of jackets or when lining gets sewn in. Sewing machines have been around since the 1850s, yet even today they cannot entirely replace hand-stitched seams although they try to resemble them.

Many people spend significant sums of money on sewing machines, but unless you are using the computerized functions of fancy sewing machines on a regular basis, spending exorbitant amounts is a complete waste of money. To make tailored couture garments all you need is a machine with a simple straight stitch; this is what is used in all the tailoring workrooms. The simpler something is, the less likely it is to go wrong. Old machines are very solidly built and many of them can last for several generations.

The foot pedal operated machines, whether industrial or domestic, a Singer sewing machine, old or new, will be an excellent brand choice, preferred by some tailors, although they might seem anachronistic. Sometimes the precision required in couture work means that the fast, industrial machines are unsuitable. It is rather unfortunate that just these are being used at fashion colleges. Amongst the good domestic machines are Swiss-made Bernina, which the author would recommend above others.

Whatever your choice of machine, it is important that you look after it, protect it from dust when not in use, and clean and oil it regularly. If you are starting out in tailoring, it is recommended that you buy a basic, good quality machine with a straight stitch and blow the budget on good scissors, which are expensive.

For your machine you need needles in various gauges. For very fine fabrics and all silks No. 70 sewing machine needles are required; No. 80 is a good, all-round needle that will sew most medium-weight fabric. A No. 90 or No. 100 should be reserved for very thick fabrics, top stitching, and so on. There are also special needles available, such as a ball point for knitted fabrics and needles for denim and leather.

Experiment using different threads with different gauges of needle and always do samples to check the tension is correct.

Hand sewing

NEEDLES

These are available in various lengths and thicknesses and are numbered accordingly (the higher the number, the thinner the needle). When buying hand sewing needles make sure that the end with the eye is not thicker than the needle itself, as this will make it cumbersome to push through some fabrics repeatedly. For general sewing, Sharps No. 9 is a suitable needle, but for felling and padding some tailors prefer to use a very short needle, such as Betweens No. 9. The shorter the needle the faster it will pass through your work, but someone sewing slowly with a short needle will still take longer than someone fast with a long needle. A long needle should really only be used to tailor tack. John James is a UK brand of superior quality. If your needles or pins go slightly blunt, push them repeatedly into a little cotton sack containing emery or strike them over a piece of leather.

THE THIMBLE

There are open-top and closed thimbles; the latter are usually used by dressmakers. Most students and home sewers do not use a thimble; some do not know how to use one. It takes getting used to, but once accustomed to it you will not want to be without it. Open-top thimbles are traditionally used by tailors, who use the side of the finger to push the needle through their work, rather than the tip, which has less strength. When stitching together several layers of heavy fabric and canvas, when padding for example, you will appreciate the use of a thimble as without a thimble your fingers would go raw after some hours’ work.

The best thimbles are made from steel and if you are lucky enough to find any, get the brass-lined ones that are no longer in production. Try to get a thimble that is dented (to accommodate the tip of the needle) all over. Avoid those thimbles with a ridge half-way down and the rubber-covered ones offered by some quilting supply companies. The rubber coating will come off after a while.

Thimbles come in different sizes, so make sure it fits. Once it is on your middle finger, the only correct place to wear it, it should not come off again unless you pull it. It helps to moisten the finger with your breath before putting it on, as the thimble will stick to your skin.

BASTING COTTON

Since this thread is only used for temporary marking and basting seams and is removed entirely after it has served its purpose, it must be seen as a tool also, rather than a material employed in the manufacture. Basting cotton is loosely twisted un-mercerized cotton yarn. Because of this it will break very easily, so it cannot damage seams when garments get ripped apart after fittings. It is used for all temporary basting on a garment and also for tailor tacking.

Cutting

Scissors

The saying, ‘your work is only as good as your tools’ is certainly true for scissors. Scissors may be anything in length below 6 in/15cm; bigger than that they are referred to as shears.

Try not to drop scissors as this could permanently damage them. Only use them for cutting cloth, never paper, as this will make them go blunt very quickly. Keep a pair of less good shears for cutting tough fabrics, canvas etc. Clean the blades regularly, to prevent lint from settling near the pivot point. Clean them with a few drops of oil on a clean cloth and rub the blades. Also use oil on the screw to keep this supple.

CUTTING SHEARS

For cutting cloth an 8–12 in (20–30cm) pair of shears is recommended, depending on the size of your hands and type of cloth that you use most often. If you can afford only one, buy a 9 in/23cm one, as this is the most useful size.