Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ubooks

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Deutsch

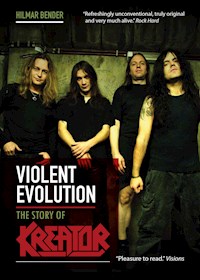

VIOLENT EVOLUTION tells the story of Kreator - the titans of teutonic thrash - from the coal-mining town of Essen, Germany. It is the story of a group of bored teenagers who brought the brutality of everyday life into the rehearsal room. They let their hair grow, formed a band and landed a record deal before they had even reached twenty. Drawing on exclusive interviews with the band's members (both past and present), family, producers, filmmakers and crew, Violent Evolution explores the band's remarkable rise from formative years to spectacular success, headlining the greatest open-air stages on the planet. This is their story, from the start to today; from Kindergarten (literally) to rulers of the Thrash Kingdom. An exciting chronicle of one of the most important thrash metal bands in the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

VIOLENT EVOLUTION

THE STORY OF

HILMAR BENDER

Translated and edited by Emma Östmann and Kathryn Fetteroll

Second Edition, April 2013

Copyright © 2011, 2013 by Hilmar Bender

Cover: Andreas Schmidt and Emma Östmann

Original German title:Violent Evolution

– die Geschichte von Kreator

Released by Ubooks, Germany

Translated and edited by Emma Östmann and Kathryn Fetteroll

with special thanks to Hilmar Bender, Joyce Fetteroll and

the Mille Militia Mädels – www.facebook.com/groups/306536389383810/

ISBN 978-3-944154-95-4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced, in any form or by any means,

without the prior permission in writing of Ubooks-Verlag.

Did you like this book? Tell us what you think at:

U-Line UG (haftungsbeschränkt Neudorf 6 64756 Mossautal Germany

www.uline-store.de | www.u-line-verlag.de

Special thanks to photographers Siarhei Hahulin, Christian Hasselbusch (www.c-hasselbusch.de), Harald Hoffmann (www.haraldhoffmann.com), Natalia Stupnikova and Pieter Verdoes. Thank you Andreas Stein, Roberto Fioretti and Frank Gosdzik for sharing your

For my little son.

A new breed has formed here, with tone and manners in common, and all the advantages and disadvantages of the young: freshness, mixed with an easygoing, almost colonial, barbarism. The province – the Ruhr region – does not open itself up to strangers. It is averse to visitors, suspicious of idle people, and the tourist facilities are only for casual visitors, not for those who want to stay. [...] Only hard-working people are sought after, invited, welcomed here. And yet, the Ruhr region still has its attractions. It still smells of money; of hard-earned, easily-frittered-away money; mercenary money, 10-day-wages, measured in material things.

Heinrich Böll, 1958

(Translated from the German originalIm Ruhrgebietby Heinrich Böll. In Werke, Kölner edition, volume 10. © 1958, 1967, 2005 Kiepenheuer & Witsch GmbH & Co. KG, Köln)

WE ASKED FOR AN ENGLISH EDITION AND THEN ENDED UP DOING THE TRANSLATION OURSELVES

“Hey, Kat! What do you say we give the people the background story to how all of this came about?”

“Of course! I think people would enjoy hearing how all this madness was born! Between broken computers, Kreator concerts, balancing life and full-time jobs, switched deadlines and battling words for months, we managed to pull off a translation of something we ourselves were so excited to read! Emma brought the idea to life, and we ran with it! So she should tell the story of how everything actually came into being.”

“Yes! This whole thing started on Christmas Eve 2011. I wrote a message to Cindy in Australia, because on her Facebook profile it said, ‘I love it when Mille yells!’ This girl must be as crazy as I am, I thought. A couple of weeks later we started a Facebook group, the Mille Militia – International Miland Petrozza Appreciation Society for Women, and began posting Kreator photos, interviews and YouTube clips. The group grew and today we are 47 members from all over the world – women only – except for Hilmar, who is the only man allowed because he wrote this book. But what is the Mille Militiareallyall about, Kat?”

“Appreciating Mille! Everything to do with him and his music! And we really do mean everything, too. Which is how I originally found the Militia, wandering around on the internet until I found a place where I could share photos, videos, stories, my artwork and worship in the Temple of Mille … or I mean, discuss matters in a group of cool, like-minded people on the internet. Yes. That then led to me joining Emma on her endeavor to translate this book!”

“Yes, that’s how it all started a year ago. Actually, I think it was Lorena from Brazil (another one of the Mille Militia Mädels) who first suggested we should do the translation ourselves. Some of us had already readViolentEvolutionin German, and we knew there was a great demand for an English version. Also, this new edition provided a great opportunity to share some of the rare photos we have found, and Kat’s amazing Kreator fan-art! Some of those drawings now illustrate this book, along with lots of exclusive photos – both new and old. And stories, stories, stories! There are so many interesting little tour stories and anecdotes in this book already, but we have even more! Please share that funny elevator story, Kat!”

“Yes! One of my favorite Kreator stories was told to me by Kurt Brecht of DRI: Back when the two bands were touring together in the late ‘80s, it took Kurt a few shows to catch a whole Kreator set. Finally, he was able to and one song in particular stuck out for him. Later on, Kurt ran into Mille in the hotel elevator. Psyched to tell Mille how much he liked the one specific song, he told the Kreator frontman which one it was. Mille’s expression of excitement dissolved to despair. When Kurt asked why, Mille explained, ‘That song you mentioned. It’s called “Lambs to the Slaughter.” It’s a cover song. The only cover song we do!’ It was a very awkward rest of the elevator ride after that for the both of them.”

“Hahaha, poor Mille! I have another funny story first hand from Mikael Stanne of Dark Tranquillity. This was also back in the late ‘80s, and Mikael and his friends had a garage band in Gothenburg, Sweden. Their first really important musical influence was Kreator’s ‘Flag of Hate’ on vinyl, bought at the local record store. (Mikael told me how they bought everything that came out on Noise Records, because ‘how can you not trust a German record label?’) Anyway. Mikael was blown away by ‘Flag of Hate’ and wanted to do a cover of the song with his own band, but he couldn’t make out the lyrics! What to do? He somehow managed to get hold of the phone number to Mille’s parents in Essen, Germany (this was when Mille was still living at home), called them up and asked if he could speak to Mille. He wanted Mille to read him the lyrics to ‘Flag of Hate’ over the phone!”

“There are too many ridiculous and silly stories to tell about the translating process too, most of which happening on very little sleep and overdosing on Kreator at hours of the night no one should be up editing passages about headbanging cows. Or the mysterious drug, Prolofan. But that’s what this was all about: having a blast doing the coolest job two Kreator nuts could ask for. Translated with loving care by fans for fans! Lots of loving care!”

“Oh yes! All for the love of God of Riffs! We asked Mille once in an interview how it felt to have his own female fan club; did it make him feel proud or embarrassed? Mille answered, ‘Both!’ … (Sorry Mille, we didn’t mean to embarrass you! :-)”

“I think the best way to sum up the Mille Militia is at the end of this book where Emma has lovingly captured one of our finest moments getting quite excited over the infamous Kreator Beach Picture. Going into detail about how I felt when I first saw that would not be safe right now. So go look at the picture instead and enjoy the craziness that ensued!”

“Ooo, I feel a little bit embarrassed myself right now! Haha! But that photo is just too good not to share with the rest of the world. Thank you Kreator for the inspiration! And special thanks to Hilmar, who has been extremely supportive and put up with our endless questions. We would never have pulled this off without you. Thank you, Hilmish! I hope we did your story justice.”

“I’d also like to give a shout out and thank my mother, Joyce, for stepping in when my computer decided to quit on me in the middle of editing! Right close to the deadline! She really saved us.”

“Thanks Joyce! And very special thanks to Cindy Karastanovic and the Mille Militia Mädels worldwide – all of the same blood! And finally, thank you Kreator for the music! Thanks to the former band members and especially to Mille, Jülle, Speesy and Sami. Without you there would be no story to tell!”

Emma Östmann and Kathryn Fetteroll

Stenungsund and Dearborn Heights

January 2013

PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION

Crossing borders has been usual for Kreator since the very early days. They already hopped the ocean to play America at nineteen, and continued to unite thrash metal fans all over the world for the next 25 years. Until recently, when they got deliberately hampered to play a Middle East show by border officials. 2000 fans from surrounding countries had already gathered in Istanbul. A simple clue that shows: terror prevails.

But, thank god for the internet, other boundaries untied. This is how I met Emma, Kat and the Mille Militia. These guys spent a lot of enthusiasm to spreadViolent Evolutionaround the world, by translating it into English. Thank you for enhancing this book. It was a pleasure.

Hilmar Bender, January 2013

This book is based on narratives by:

Mille – Miland Petrozza – Guitar, Vocals

Jülle – Jürgen “Ventor” Reil – Drums

Rob – Roberto Fioretti – Bass

Tritze – Jörg Trzebiatowski – Guitar

Frank Blackfire – Frank Gosdzik – Guitar

Joe Cangelosi – Drums

Tommy Vetterli – Guitar

Speesy – Christian Giesler – Bass

Sami Yli-Sirniö – Guitar

Stoney – Andreas Stein – Merchandise, Kreator-Museum

Ulsch – Ulrich Weitz – Tech, Driver

Boggi – Bogdan Kopec – Management

Karl-Ulrich Walterbach – Founder of Noise Records

Manfred Reil – Father

Barbara & Piero Petrozza – Parents

Andreas Marschall – Graphics, Filmmaker

Thomas Schadt – Filmmaker

Sung-Hyung Cho – Filmmaker

Stephanie von Beauvais – Filmmaker

Moses Schneider – Producer

Nagel Mann – Singer, Writer

and

Stefan Remter

Markus Tenbergen &

Christoph Dreher

IT AIN’T WHERE YOU’RE FROM, IT’S WHERE YOU’RE AT

Miland Petrozza stared into space. He dropped his guitar case on the floor and pushed the strap of his duffel bag from his shoulder. Never before had he returned home feeling so useless. He could still feel the back slaps from the show the night before, but the last few hugs and handshakes had felt more like farewells to the best times of his life. The band was in shambles. Metal was on its deathbed. It was late February 2000 and everything Petrozza had lived for over the last fifteen years had ended.

The tour with the young, gothic metal band Moonspell as a headliner had been a painful farce. With all due respect, Kreator opening for Moonspell? Nobody had made any money from the tour. Management, promotion, line-up, producers – nothing fit together anymore. Too much smoke in the air, too many ice cubes in the bong, too many false notes played.

Farewell, youth ofThrash, Altenessen. Welcome, age of tedium, Essen.

One more band dumped, like overburden on the coal mine spoil tip: wrung out, lifeless, worthless. Nothing justifies the existence of a band that doesn’t believe in itself anymore, a band whose audience only loves them for what they used to be in their glorious past. To leave everything behind would be so simple.

But Miland Petrozza doesn’t give up that easily. He thought of his band mates. He thought of Speesy, of Jülle. Mille made a call.

“We need to talk. We have to remember what made us great, what made us something special. We have to go back to our roots and get that old energy back. We need new blood – call the Finn! He fit in well when he toured with us two years ago. We need a fresh start. Fuck writing for the record company! We’ve got to take everything back into our own hands. We have to keep thrashing, blow everyone away and remember how it all started!”

One part of this story was born deep in Calabria in the toe of Italy’s boot, where the sun beats down relentlessly and you had better find yourself shade lest it burn you to a crisp. There, a shoemaker fed his family from film screenings and making prosthetic limbs for soldiers who lost their real ones in the last war. This life sustained his family until the shoemaker passed on, leaving his 12-year-old son to look after his mother. Some years later, the son decided it was time he seek his fortune somewhere far away.

Another part of the story began a bit further north, in L’Aquila, not far from Rome, where the earth threatens – with terrible grinding noises – to swallow up the houses, with no regard for how many hundreds of years they have stood. From there, three brothers went to Germany and one to France in search of happiness.

Finally, the roots of this story also grew in Poland, East Prussia, as well as east of Berlin, in places where hardly anything remained after the World War II commanders and their troops had ravaged the area.

Kowalski, Schimanski, Petrozza, Kokoschinski, Wiesioreck, Kopec, Fioretti, Grzeca or even Trzebiatowski. Whatever name it was your parents carried, a common denominator among the boys was that their surnames looked absurd. You had to figure out some way to pronounce them, so consequently, the names soon turned into nicknames. This potpourri was a normal expression of a motley crew. Demarcation unnecessary. Solidarity inevitable. No matter if you were Italian, Yugoslavian, Turkish, Polish; or whatever, your nationality was just another personal characteristic rather than a social division.Unter Tage*sind alle Fratzen grau. Down in the coal mines, all faces are grey. Everyone was the same; all human. Only there, where a glimpse of blue sky, a breath of fresh air was never found, did the fathers meet. From them is where this story derives its origin.

*Translator’s Note:Unter Tageis a German expression for working in the mines, literally “below daylight.”

The Ruhr region, 1970s. Northern Essen, Altenessen.

In the shadow of the highway, Emscherschnellweg, a street called Hohendahlstraße bends in a U, right across the road from the Emscher School. Around the corner to the right is the Thiesstraße, where, within a few yards of each other, a gaggle of boys all around the same age grew up together. Their fathers worked in the mines while their mothers stayed home to tend to their broods. The apartments were small, the families large, and the boys’ childhoods, through their teenage years, were lived in the streets.

Young Jürgen was eager to help when his father and their neighbor worked on their cars through the evenings, tinkering away. “They did everything themselves. When the transmission case broke down, they went to the junk dealer for replacement parts. My father first had a Käfer, then an Opel Rekord, then an Opel Granada, and our neighbor had a Commodore. They even exchanged engines right there in the yard in front of our neighbor’s garage. They built themselves a derrick with a winder that my father got from the mines. That’s what they used to lift the engines out. As a little kid, I used to hang around them all the time, watching. No wonder I wanted to be a mechanic later on. That way I could always help my father out.”

Working in the coal mines was out of the question for Jürgen. “My father had told me all the horror stories. Even then he said to me, ‘You can do whatever you like for a living. Anything at all. But I do not want you to be a miner.’ He did not want that for me. Obviously, he wore his arguments in plain view: On his shoulders were coal scars made blue from the coal trapped under his skin, and marks from the biggest to the smallest accidents he had endured.”

Despite this, father Reil worked in the mines, well aware of the risk that his son might have to grow up without him. A little more than two years later, when Jürgen’s younger brother was born, Mr. Reil changed jobs in the coal industry and stopped his work in the mines.

He keeps an old photograph in his house: of Jürgen standing in line with Miland in front of a slide.

“The kindergarten was right down the road from us. I’ve known Miland for thirty-eight years now.”

Mille’s family lived just around the corner. There was always music playing in the Petrozza residence. “My grandfather played the banjo and the piano. My father played acoustic guitar in an Italian orchestra. That was in the ‘60s. They played at dances on Sundays, and from time to time he sang with the Italian Catholic congregation. Father was a music fan with a very broad, varied taste in music. He liked everything from Italian operette to German schlager. I learned early on not to limit myself to a single genre of music. Father recorded everything that was on TV. He recorded the sound from the TV using a special cable: disco, hits and the showMusikladen. We listened to the tape over and over until the next show was on, and then we used the same tape again for the next recording.”

Mille, a comic book nut, devoured everything from Marvel that he could get his hands on.Spider-Manin particular appealed to him. This interest is what drew him to the KISS characters in their makeup, like superheroes themselves. “We stood in front of the KISS posters in Karstadt. It was glamour, it was surreal. I was most fascinated by the cat character.”

At thirteen, a dream came true for Mille: KISS had an internal band crisis and cancelled the tour, but they were coming back to Germany the following fall. Everyone who listened religiously to Mal Sondock’s radio show on West Germany’s radio every week was up to date. (Sondock was not only the one who brought American pop culture to West Germany, he was also a self-declared buddy of KISS.) Mille begged his mother to let him go to the Philipshalle in Düsseldorf. That way he could experience KISS a couple of days before everyone else in the Ruhr region, since the show in the Westfalenhalle in Dortmund was already sold out. Mille was allowed to go, in the company of his older cousin. He describes his memories from the show inRock Hardmagazine, issue #250:

The train ride itself was an adventure! There were all sorts of cool people on the train, some of them in makeup like Paul, Gene, Ace or Peter (even though the drummer had left the band before the tour in Germany and was replaced by Eric Carr – the fox). There were lots of rockers with long hair as well as many pretty girls on the train. I felt like the odd one out in my very uncool kiddy anorak that I used to wear at the time, but in the parking lot outside the Philipshalle I bought myself a tour scarf. Now I belonged!

The opening act was an unknown band called Iron Maiden. They were pretty cool too – mostly because of their monster that came out on stage during the last song – but I was waiting for my American heroes!

The temperature was rising. After Maiden the hall was lit up again and I saw how big the crowd was. In Essen, my hometown, I knew maybe five people who liked KISS, and here there were thousands! [...] I can still remember that I started to scream like a madman when the lights went out, and did not come to my senses again before the end of the show. In between, I tried to sing along to the lyrics in my kiddy English and couldn’t fathom what was going on on the stage. I had never seen anything like it in my life! KISS was the essence of everything I loved as a child: comic characters that played totally heavy music: Gene – the demon that spat blood; Ace – the space man; Paul Stanley and Eric Carr; fire, explosions and a mega light show. Total terror! Genius!

It felt much too short, even though it was a normal length show. I wished it would never end. It was difficult to convey to my friends what I had seen, and still today it is not easy to describe an experience like that in something as trivial as words. Anyone who cares about music can remember their first live concert as a truly remarkable – sometimes even life changing – experience. [...] The message you can find in a good song that comes from the heart is ‘true’ beyond comparison. Much more so than anything society wants you to believe is truth.

Being a musician means absolute freedom to me; to be able to express myself and turn my negative energy into something positive that I can share with other people. Still to this day there is nothing greater for me than to create a new exciting song out of, as it were, thin air.

When the lights go down in the hall at my own concerts, I still scream like a madman from the stage. Sure, I’m singing my own lyrics now, but the feeling is very similar to what I experienced in the Philipshalle in the beginning of the ‘80s. Without sentimentality, I can truly say that September 12, 1980 completely changed my life for the better.

Back at home, Mille spent hours meticulously building his own guitar from Styrofoam. He put a lot of love and effort into the realization of his very own “Iceman,” complete with silver foil; the same guitar that Paul Stanley played. In his bedroom in front of the mirror, Mille practiced all the poses he had seen his idols strike on the stage. “But I was too wild and ruined the guitar. Michael Wulf was mad at me and hit me over the head with the sad remains of it, and all my hard work was ruined. That was it: I needed a real guitar.”

Jülle was not that interested in guitars. He had a lot more fun being the makeup artist for the boys. He took on the job of doing everyone’s KISS face paint.

While Mille took his first guitar lessons, Jülle turned his attention to the drums. “I practiced at home using long pencils. They were thick ones, souvenir type, with pictures of the Schwarzwald and big erasers on the tops. My grandmother had bought them on holiday – one for me and one for my brother. I built myself a couple of boxes and practiced on them with our pencils.”

This was in an age long before music television and the internet, and information was hard to come by. But Jülle was lucky. “We got to know this rock band that lived a couple of blocks away. (The Hopeless Rears – later Indigo Dawn – still local heroes in Essen.) The first time I got to play on a real drum kit was in their rehearsal room. ‘Come on Jülle, play something!’ they egged me on, eagerly. ‘But I can’t!’ I said. The band had a lot of fun on my behalf. ‘Bullshit! Just sit down and give it a go!’ they insisted.”

Jumping into something takes courage. The first step is always the hardest. “But I wasn’t completely unprepared and I did have a certain natural talent for it,” Jülle says. “Anyway, after that initial jump I was hooked for life.”

The next time Jülle had a chance to sit behind a real drum kit – rather than one made out of boxes and pencils – was at a music expo. While a crowd gathered around Mille (amused commenting on his loud vocal attempts in the amp department), Jülle tried out their material on the drums.

“We went to the music expo very self-assured; we called ourselves musicians! Haha!”

Soon after that, a drum kit of his own was on top of Jülle’s wish list. “All of us went to talk to my father together. I said, ‘Let’s all of us go and ask him.’ I thought that if we had us all there, maybe we could convince him.” But drum kits are expensive and Manfred Reil could not manage the 2,000 DM** needed. “I had 1,700 DM from my confirmation in a savings account, and my father contributed the rest,” remembers Jülle. “We went to Musik Axel and then we were ready to go. Naturally, we couldn’t put the drums in our house. Now we needed somewhere to practice.”

**TN:Deutschmark(DM), the unit of money used in Germany before the euro.

On a different front another spark was building:

“Hey, guitar teacher, we don’t want to play ‘Get Back’ and ‘This Land Is Your Land’ on the acoustic guitar anymore. Teach us something by Ace Frehley. That’s what we want to play.”

“Excuse me?”

“Well, why else would you have an Ibanez poster on the wall?”

“All right, all right. Funny, boys. You can’t even play anything yet – but you want to try out the Les Paul? That’s what you had in mind? Well, it’s not going to happen!”

“Come on, Wulf, let’s get out of here! We don’t need this! Let him try that Peter Bursch*** crap on somebody else.”

***TN: Peter Bursch, famous German guitar teacher.

The Karstadt shopping center in Altenessen provided the essential ingredients to add to the bubbling Kreator broth; the base for what would later become the Kreator we all know. Four boys pressed their noses flat against the shop window. There was a special offer on display: an electric guitar for 260 DM. All of them managed to scrape together the money and each bought one of the guitars. Before the band was even fully fledged, they had more guitar players than any band would ever need: Roberto Fioretti, Michael Wulf, Michael Huizkez, Miland Petrozza and yet another guy on bass. Since the shop only had three guitars at the special offer price, Mille bought himself another model, just a bit less terrible than the cheapest line.

“Okay boys, let’s start a band.”

Michael Wulf’s basement was cleared out and given a good cleaning. In the spirit of the times, they used the standard low-tech solution for noise reduction: All the walls were plastered with egg cartons, ‘80s-style. Finally, they were good to go. Everyone who owned a guitar and dared to, wanted to, had to join. Yet only three weeks later, the evolution of the band began: Michael Wulf quit. He had realized that, while Mille had a menagerie of good riff ideas, he himself had none. So Wulf decided they needed to go their separate ways, and he made plans for a band of his own. Wulf’s parents took advantage of the situation and kicked the band out of their basement.

Mille is still convinced Wulf’s parents had had their own agenda. “They just needed somebody to clean out their dusty old basement. That was their plan from the start, I’m sure of it. They wanted a good storeroom for their liquor store down there. So we threw out all their rubbish for them, cleaned up and renovated the thing,” Mille says with a sneer.

“Our old guitarist’s mother thought we were too loud, and that’s why they kicked us out. Of course, before that, we had spent hours upon hours scouring their shitty old basement, full of 400-year-old plums,” Jülle asserts.

Mille had realized, from a musical point of view, that their first line-up had been doomed from the start. “It was obvious that we couldn’t possibly have four guitarists, all with different ideas. Or, to be honest, some of them had no ideas whatsoever.”

After being kicked out of the basement, the band began their first serious attempt at making music. Now, only Roberto, Mille and Jülle remained in the band, sharing their interest in music. They found a rehearsal room in the basement of the youth center and started out by playing cover versions of “Breaking the Law” and dabbled with some Twisted Sister. Mille even mastered one of Led Zeppelin’s riffs, but that wasn’t considered cool enough by those around him.

“Stop playing that. That sucks.”

Jülle listened to Judas Priest’sBritish Steelon headphones and played along with the recording. The others joined in on their instruments. The young musicians hungered for songs they could jam along to, but their talents had yet to catch up to what their itching fingers yearned to play. Iron Maiden was too complex for them, KISS too difficult. Still, they really wanted to play whole songs right away. The band was stuck on the first level. And it didn’t help that they were plagued by one very big problem: They had no singer.

“In the beginning, everyone wanted to play guitar and I was supposed to be the singer,” Jülle explains, “but that was before we had even fully formed the band. We thought it would be cool to have a big front man, and I didn’t want a guitar anyway. It wouldn’t look good on me. I’ve always been too big for a guitar.”

Since they couldn’t find another drummer, Jülle announced: “‘All right. Then I’ll do both. I’ll play drums and sing at the same time.’ The only problem was that there were so many songs. Then more songs. Before long, I was out of breath. Thus, I started sharing singing duty with Mille.”

Mille, in his turn, was happy that Manfred Rehberg showed up. Manfred wanted to be a singer and had talked his father into buying him an expensive vocal amplifier. A good 3,000 DM went over the counter for that one. “Then we got a rehearsal room in the youth center where we always hung out anyway. Every now and then we had a singer (the guy with the vocal amplifier),” remembers Jülle. “We had to persuade him into rehearsing every time, and more or less go pick him up from his parents’ house to get him to come to practice. At first, we had no problem with that, but then we started to see less and less of him until, eventually, he wouldn’t show up to practice at all. After some time, we decided his amp was better than our guitar amplifiers, so we simply used that for our guitars, bass and vocals together until it inevitably melted. After that we started rehearsing in the girls’ room in the youth center instead. Once we were finished with practice for the day, we would have to shove all of our stuff into one corner and cover it up so the girls wouldn’t touch it.”

Obviously, it was time for a better solution.

In the block where they all grew up, where the Hohendahlstraße forms a U (near the walkway between the school and the kindergarten), is the Emscher School Youth Center. It was once a special needs school, and now they were going to let the boys use the attic above it. The attic, under the huge, pitched roof of the building, was completely empty and became the band’s new rehearsal room. It seemed brilliant. That is, until the first rehearsal.

“It got really hot in the summer and there was no insulation in the room. One day the pastor came by. Behind the kindergarten was the Catholic Church, and every sound from the attic could be heard clear as a bell from the church building. Only a thin wall separated them. The pastor was showing the youth leader around the church and discovered the church windows rattling away from our playing.”

And that was the abrupt end to what seemed to be a perfect solution.

“But those people went out of their way to get us somewhere else to rehearse. They were really cool that way. They were completely on our side. In school, everybody took us for complete morons. If you told anyone you were in a band, it was just like, ‘Yeah, right! Get out of here!’ Everyone was like that, from the headmaster of the school to the substitute teacher. Everyone except my class teacher. She was cool,” Jülle remembers.

Barbara Petrozza has not forgotten about when her oldest son was almost expelled from school because of his long hair and the band logos he had painted everywhere. They made him wash off those marks before he changed schools.

“I had a talk with the principal of the school on Mallinckrodtstraße. He was a local CDU (Christian Democratic Union) politician,” says Barbara. “When they won an election, he boasted about it all over the area. ‘Just you let that boy walk around as he pleases,’ I told him, ‘and before you expel him from this school, I would prefer to take him out of it myself.’ After that, Miland started attending another school in Karnap, where he graduated without any difficulties. The school itself had been the problem, not the kid.”

“I learned more about life from metal than anyone could have ever taught me in school,” Mille says with confidence.

Besides the benefit of reduced stress over the faculty, the change of schools offered the bonus of new classmates to make contacts with. “Mille had to change schools, and ended up at Karnap, which was where I was attending at the time,” says Tritze. “He was a big Judas Priest, Saxon and Hawaii fan, and he used to call me Udo, because I was ‘the guy with the hat.’ I was an Udo Lindenberg fan and he was a real metalhead, complete with leopard stretch pants, leather motorcycle jacket and long hair. We would sneer at each other in the beginning,” laughs Tritze. “Then came our connecting link: Udo Lindenberg releasedDie Keuleand Don Dokken played guitar on it. Because Dokken was featured on the Lindenberg LP, Mille and I started talking to each other. We’d found something we were both interested in.”

Jörg “Tritze” Trzebiatowski from Essen Karnap was the singer in another rock band, and soon, his combo and Mille’s band shared a rehearsal room together. “I went along to the first Tormentor show as Jülle’s personal drum roadie,” says Tritze. “I was a singer and a Lindenberg fan, so it was only logical that I turned to the drums, because that was Udo’s first instrument. I pounded away on Ventor’s kit and anything else I came in contact with, and I thought it was so much fun. Next, I started getting into the technical aspects of assembling drum kits, rather than just playing them. It’s really interesting how you put something like that together. So there you have it. All of a sudden I was a drum tech.

“In the meantime, I had picked up practicing the guitar a bit too, with no real aspirations to go far with the instrument; I had mastered a couple of barre chords. Mille was a real inspiration to me, and I thought learning guitar would be pretty cool, too. When Mille played Judas Priest songs through his Marshall, it sounded exactly how it did on the albums! I found that totally fascinating. The arrangements of heavy metal songs were very minimalistic. To be able to play a Lindenberg song – and make it sound even remotely like it did on the album – you needed so much more. For something like Saxon or Judas Priest, a single guitar was enough; you would just start playing and it sounded like Priest. I found it amazing that with so little to work with, you could create so much emotion.”

Soon, it was time for the group’s first performance. The Emscher School provided everything the boys needed to make it possible. It was like a giant playground for them. “Before the show, the social workers had made a backdrop with a message to hang up behind us on the stage. ‘HEAVY METAL FOR PEACE’ was emblazoned on large pieces of paper behind the drums. What’s with all this shit? For peace? No way! We were different. We were terror! That backdrop had us concerned, and in no time, we’d ripped down the ‘FOR PEACE’ and left the ‘HEAVY METAL’ to fly high. Now, finally, everything was complete to put on our first show.”

Before then, the band was still called Metal Militia, but the name was switched around on a weekly basis. “As a general rule we used song titles from bands that we were into at the moment for our moniker.”

Show time was drawing near, yet the band’s singer was nowhere to be found. He hadn’t shown up for rehearsals. He had chickened out. The rest of the band had decided he was out for good anyway, but what would they do without a singer? Their first solution was that Jülle and Mille shared the singing duties between them. Their songs were called “Shellshock,” “Shoot them in the head” and “Heavy Metal Fight.” Some bad-ass song titles.