9,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: AJP

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

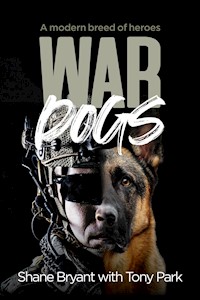

One man and his four-legged friends go to war in Afghanistan; a ten-year battle against enemies seen and unseen

In Afghanistan, sometimes all that stands between coalition troops and death or serious injury is a dog. Highly trained dogs and their handlers search for improvised explosive devices or hidden weapons out on patrol with combat troops.

It’s a perilous job, often putting them right in the firing line, and making them high priority targets for the Taliban insurgents they’re fighting.

Shane Bryant, a former Australian Army dog handler, spent 10 years in Afghanistan, working with elite American special forces alongside his four-legged buddies, Ricky and Benny, and managing teams of dogs and handlers.

War Dogs is Shane's story – a riveting tale of handlers and their dogs in combat, and a brutally honest account of how a decade as a contract warrior took its toll on Shane’s personal life and his mental health, and how he found hope again.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

About War Dogs

One man and his four-legged friends go to war in Afghanistan; a ten-year battle against enemies seen and unseen

In Afghanistan, sometimes all that stands between coalition troops and death or serious injury is a dog. Highly trained dogs and their handlers search for improvised explosive devices or hidden weapons out on patrol with combat troops.

It’s a perilous job, often putting them right in the firing line, and making them high priority targets for the Taliban insurgents they’re fighting.

Shane Bryant, a former Australian Army dog handler, spent 10 years in Afghanistan, working with elite American special forces alongside his four-legged buddies, Ricky and Benny, and managing teams of dogs and handlers.

War Dogs is Shane's story – a riveting tale of handlers and their dogs in combat, and a brutally honest account of how a decade as a contract warrior took its toll on Shane’s personal life and his mental health, and how he found hope again.

This book is dedicated to my five beautiful children: Corey, Lauchlan, Demi, Kyron and Jaylen. Every minute I have been away, you have always been in my heart and thoughts.

CONTENTS

GLOSSARY

.50 cal – .50 calibre Browning heavy machine gun. First used by the American Army in World War I and still in use today.

1 CER – 1 Combat Engineer Regiment.

240 – 7.62-millimetre light machine gun, adopted by the US Army as a replacement for the Vietnam-era M60 machine gun.

A-Team – Officially Operational Detachment Alpha, a twelve-man US Army Special Forces team.

AC-130 ‘Spectre’ – C-130 Hercules cargo aircraft configured as a gunship, armed with 40-millimetre cannons, six-barrelled 20-millimetre ‘Gatling’ guns and 105-millimetre howitzer.

AK-47 – Russian-made Kalashnikov assault rifle, in widespread use with both Taliban and Afghan government security forces.

Alice pack – The common name for the US Army’s aluminium-framed LC-1 backpack.

ANA – Afghan National Army.

Apache – US Army helicopter gunship, also used by the Dutch in Afghanistan.

B-Team – Officially Operational Detachment Bravo, US Army Special Forces administrative and headquarters element overseeing a number of A-Teams.

B1 Bomber – US Air Force supersonic strategic jet bomber, designed to drop nuclear bombs on Russia, but now in use in Afghanistan.

BBDA – Back blast danger area, the out-of-bounds area behind an anti-armour weapon while it is being fired.

Bison – Canadian armoured troop carrier, a smaller version of the light armoured vehicle.

Black Hawk – US Army troop carrying and medevac helicopter.

Brown Ring – Code name for regular supply run circuit flown by Chinook helicopters to firebases in Uruzgan Province.

C-17 – US Air Force medium-lift cargo jet.

C-130 – Four-engine Lockheed Hercules cargo aircraft.

CAI – Canine Associates International.

CANSOF – Canadian Special Operations Forces.

Carl Gustaf – Swedish-made 84-millimetre shoulder-fired anti-armour weapon used by US Special Forces.

CH-47 Chinook – Twin-rotor cargo helicopter, first used operationally in the Vietnam War, with variants still in service today.

Dooshka – Soviet-made DshK 12.7-millimetre heavy machine gun.

ETT – Embedded training team, coalition military personnel assigned to train and mentor Afghan security forces.

FOB – Forward operating base, outlying fortified encampment typically used by a Special Forces ODA.

GMV – Ground mobility vehicle. Also known as a ‘gun truck’, a humvee with a turret on its top and open rear load space. A heavy weapon launcher, such as a .50 calibre machine gun or Mark 19/Mark 47 grenade, would be mounted in the turret, and two 240 machine guns (or similar) mounted in the rear.

Haji – US Army slang for an Afghan male, derived from the name given to believers who have made a holy pilgrimage to Mecca.

Hesco – Steel mesh container lined with hessian and filled with earth, and used as a barricade.

Hooch – US Army slang for a dwelling.

Humvee – Short for ‘high-mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicle’. US military four-wheel-drive.

IED – Improvised explosive device, usually a roadside bomb.

JTAC – Joint terminal attack controller, US Air Force air-to-ground controller, responsible for coordinating air strikes and air support.

M4 – Standard US Army Special Forces 5.56-millimetre assault rifle, a shortened version of the M-16 rifle.

Mark 19/Mark 47 – Automatic belt-fed grenade launcher that fires 378 40-millimetre grenades per second.

MEDCAP – Medical Civic Action Program that provides medical care to Afghan civilians.

PKM – Russian-made 7.62-millimetre belt-fed light machine gun in common use with insurgent and government forces in Afghanistan.

Psyops – Psychological operations.

PUC – Person under consideration, such as a suspected Taliban or al-Qaeda member targeted for questioning or arrest. (To ‘PUC’ someone means to capture them.)

RPG – Rocket-propelled grenade, fired from a Russian-made RPG-7 launcher.

SAS – Australia’s elite Special Air Service Regiment.

SF – Special Forces

Soldier’s five – Australian Army term for a short lesson, or briefing, given by one soldier to another.

Space-A – Space Available transport.

Terp – Stands for ‘interpreter’, an English-speaking Afghan interpreter assigned to coalition troops.

TIC – Troops in contact, under fire or engaged in combat with the enemy.

Turtleback – A humvee with a fully enclosed roof.

VCSI – Vigilant Canine Services International.

AUTHORS’ NOTE

War Dogs was first released in Australia in 2010. This worldwide edition has been expanded and updated.

PROLOGUE

Uruzgan Province, Afghanistan

February 2007

The rain had stopped but it was still so cold up in the mountains, it hurt.

I took out a plastic bag of dog food and fed my dog, Ricky, then looked after my needs with some chunked-and-formed crap from an MRE – Meal Ready to Eat, or Meal Rejected by Ethiopians. I was in the team sergeant’s humvee. Before he did his evening walk-around the other vehicles, he told us what was what.

‘They’re all around us,’ the grizzled Green Beret said, almost as though he were relishing this revelation. ‘I got a feeling we’re going to get hit again tonight, so stay sharp.’

I nodded. Two TICs – troops in contact, what the Americans called firefights – in one day had been pretty full on, I thought. God knows what the night has in store.

‘We’re getting lots of ICOM chatter. They’re out there and they might be looking for another fight.’ The team sergeant added that headlights moving around the hills had been spotted, which was a bad sign, as villagers knew that, due to a curfew, they needed to be indoors by six in the evening. You could assume that anyone driving around at night was doing so for disturbing reasons. ‘Don’t worry too much, though. We got Spectre overhead tonight.’

It was good to know the AC-130 Spectre gunship was orbiting up there somewhere, unseen and unheard, ready to unleash its awesome fury if needed. The AC-130 was a converted four-engine Hercules transport aircraft, which was loaded with guns and ammo. It had 40-millimetre cannons, six-barrelled 20-millimetre electric Gatling guns and even a 105-millimetre howitzer on board.

Someone had radioed that they’d seen movement, at about 300 metres from our position, which was why Spectre had been called on line. I could hear it droning above us now and so could whoever else was out there among the rocks and boulders. I felt better – no-one fucks with you when they know Spectre’s overhead.

Like everyone else in the team, I had to take my turn on picket – my guard duty shift – during the night. The US Army – particularly its Special Forces (SF) – isn’t as slack regarding discipline in the field as some people like to make out. Smoking wasn’t allowed at night, so I had taken up chewing tobacco to help keep me awake. I’d chew it while we were driving around on missions as well, to help keep me alert and to give me something to do while I was sitting behind my gun. The tobacco doesn’t usually taste too bad, like a strange-tasting chewing gum. Some of the flavours, such as raspberry, are really disgusting, but I usually went with peppermint. The Americans are all into chewing tobacco and call it ‘taking a dip’.

As usual, I had a one-hour shift. One of the only things I was scared of in Afghanistan was fucking up and letting the team down. They treated me as one of their own. When I was pulling my night shift, other people’s lives were in my hands. I sat in the truck behind the 240 light machine gun, chewing tobacco and spitting the juice into an empty half-litre plastic water bottle. I stared out into the bleak mountain night, and listened to the muted voices coming from the radios of other vehicles in the convoy.

I was colder than I’d ever been while in the army in Australia. Those days seemed a lifetime away.

When my relief came up to the truck, I eased myself down and walked around for a bit to get some feeling back into my feet, then went to check on Ricky. He was tied under the truck, curled up on his own sleeping bag. ‘Good boy,’ I whispered to him.

I spat out the last of the chewing tobacco and wished I could have had a proper smoke before going to bed. I unzipped my Gore-Tex bivouac or bivvy bag – kind of like a waterproof swag – and slid into the sleeping bag inside it, still with my boots and all my gear on. If the team sergeant was jumpy, it was for good reason, and I had to be ready to stand-to in the middle of the night. I laid my M-4 in the bivvy bag and tried to get comfortable on the unforgiving rocky ground. I was shattered, but sleep didn’t come easily as I replayed the day’s events.

It had turned out that the second ambush we’d been through, earlier that day, was just one guy with a rifle taking pot shots at us, but it had turned into a full-on TIC from our side. The Taliban always had spotters in the villages, hills and mountains, keeping an eye on us whenever we were on the move. Sometimes they’d open up on us, which, I guess, was their way of screwing with us – delaying and making us expend some ammo that we then wouldn’t have if the shit went down for real. It was a high-risk strategy for the spotters, though, as the American SF guys were always looking for a fight, and if someone called game-on, they were ready to play. Sometimes the spotter would get away, but other times they’d nail him.

I dozed off, but woke again, busting for a piss. I checked the display on my watch. ‘Shit.’ It was three in the morning. When I unzipped the bivvy, I immediately felt the almost stinging cold on my face. Reluctantly, I walked a few metres away. Steam came off the ground. When I got back to my sleeping bag, I stepped on it in the dark and heard a growl. The sleeping bag started to wriggle.

‘Ricky?’

He’d crawled right inside my warm sleeping bag.

‘Cold, boy?’ I whispered. I opened the bag and saw him looking at me. When I reached in to drag him out, he gave another low growl.

‘Very funny. Move, boy.’

Ricky growled once more. I ran a hand through my hair and shook my head. I couldn’t blame the poor guy. He was probably freezing. I took a peek under the truck and saw that his water bowl was frozen over. ‘Fuck. At least move over, man,’ I said.

Ricky growled a little again as I shoved him, but he made just enough room for me to slide back inside. We couldn’t both fit, but Ricky nestled against me near the bag’s opening. I couldn’t do it up, but as I had German shepherd hair wrapped around my shoulders and face, the cold wasn’t too bad. Ricky seemed happy with this compromise and shifted a bit. He sighed.

‘Night, buddy,’ I said to him. Bloody dog, I thought, smiling as I tried to unwind and get back to sleep.

ONE

A picture of a man and a dog

1989, Kapooka, Australia

The soldier standing in the barracks block corridor tried to move his weight from one foot to the other surreptitiously. The bombardier’s spit-polished boots shrieked on the linoleum floor as he executed a perfect about-turn further down the line of green-uniformed recruits.

‘I SAID, DON’T MOVE, YOU FUCKING IMBECILE.’

‘Sorry, Bom …’

The bombardier, which is what the artillery calls its corporals, squeaked his way down the corridor to the recruit who’d been human enough to move, and stupid enough to try to apologise for it. He stopped a few centimetres from the guy’s nose. ‘DON’T FUCKING SORRY ME.’

The spittle must have hit the recruit in the face. I concentrated on standing perfectly still, and hoped the beating pulse in my neck wasn’t visible to the bombardier’s all-seeing eyes.

Sometimes you’d get a secret laugh or sly smile out of one of the instructors’ insults, but not this time. I can’t even remember who’d done what wrong, but the bombardier had made us all fall in and stand perfectly still in the corridor. Even for Kapooka, it was a bizarre and, in its own way, sadistic punishment – just standing still and silent, hour after hour. We would march all day, or so it seemed, and we’d do the run, dodge, jump obstacle course, and we’d do more physical training and at the end we’d be sore, and sorry for ourselves, but at least we’d been on the move. I didn’t mind the exercise, because I was a pretty active kid, but making us keep rock still in one position seemed all the crueller because of the active lives we’d been leading. If standing to attention in the corridor, not moving or speaking for two-and-a-half hours, was supposed to teach us something, it didn’t work, because I can’t remember it.

Lining the wall of the corridor were big blown-up drawings illustrating all the different jobs you could do in the Australian Army. There were guys posed next to trucks, an infantryman with a rifle and fixed bayonet, an artillery dude next to a big gun and a bloke in the turret of a tank. The one that most interested me, though, was of a soldier kneeling beside an Alsatian dog. For some reason, as soon as I saw that picture I knew that this was what I wanted to do in the army. Those blokes in the pictures all looked determined – happy, even – and they’d all gone through the shit that we were experiencing today. I sincerely hoped the real army wasn’t going to be like Kapooka.

The bombardier continued prowling along the corridor, watching, waiting for another victim to move. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the guy who had moved his feet stick out his right hand, his arm bent at 90 degrees at the elbow, which is how you put your hand up if you are standing to attention. ‘Bombardier,’ he said in a high-pitched voice.

The lino now screamed as the bombardier executed an about-turn and came marching back down the line. ‘Put-your-fucking-hand-down,’ he said slowly and quietly, sounding even more menacing. ‘I SAID, NO FUCKING MOVEMENT.’

‘But, Bombardier, I need to . . .’

‘SHUT UP!’

The guy apparently had a death wish and for a moment I felt sure that the non-commissioned officer was going to punch him. Instead, the bombardier repeated his order and walked up and down the line, telling us all that we needed to learn some fucking self-control.

A little while later, with the pain burning through the thick soles of my boots and my shoulder muscles starting to cramp, I heard it. I think everyone heard it, no matter how far along the corridor they were, but no-one wanted to look. Soon, I could smell it.

I risked moving my gaze to the recruit who had asked for permission to speak. The front of one leg of his green trousers was stained black, and a puddle of piss was fanning out on the lino, around his boots.

It was my mum who encouraged me to join the army.

I was born in Leichhardt, in the inner-western suburbs of -Sydney, where we lived until I was five. After that, we moved to Dapto, on the New South Wales south coast, which was a big change from the city’s cramped terrace houses and narrow streets.

I have two sisters and a brother, and am the oldest by five years, so I found myself doing quite a bit around the house after my folks split up when I was in fifth class. Later, my mum had twins, a boy and a girl, Reece and Naomi, from her second relationship.

Dapto’s big claim to fame is its greyhound dog racing track, but I don’t think this had anything to do with my future career choices. Dapto’s not by the beach and is pretty suburban, so I didn’t grow up a surfie, spending all my time on the sand, smoking dope and driving a panel van.

I wouldn’t live in Dapto now, but it was a good place to grow up. I started playing rugby for Wollongong, the nearest big city, when I was fourteen and that kept me occupied during my early to mid teen years. I always wanted to be outdoors, either riding my pushbike or playing sport, rather than hanging around the house.

Dogs became a part of my life pretty early on. I really wanted a Doberman, but mum bought me a cattle dog instead, which I called Sheba. I really liked being with her, and I’d walk her every day, along with a mate of mine who also had a dog. Sheba was a good friend and always happy to see me. At that stage, though, I had no thoughts of ever working with animals.

I wasn’t good at applying myself at school, and I couldn’t wait to get out and start doing something – anything. I just wanted to escape. Looking back, I wish I’d applied for a trade, or kept up with my studies. My mum wasn’t going to force me to stay on until Year Twelve, and she decided that if I wanted to leave, I should think about joining the army. My dad had been in the army, in the transport corps, so it wasn’t as though Mum was unfamiliar with the military life and all that it involved

The defence force recruiters, from the army, navy and air force, came to our school, and after their talks I spoke to the army guy. I’d already decided that if I were going to join one of the services, it would be the army. I told Mum this, and she called the recruiting office and arranged for someone to come to our house and talk to me about it some more.

The recruiter started the ball rolling and, before I knew it, I was on the train to Sydney for my medical and psych evaluation. I was told I had high blood pressure, so I had to go for more tests once I got back to Dapto. The doctor gave me the all clear and suddenly I was being sworn in as an Australian Army recruit.

I was seventeen years old and on a bus with a bunch of blokes I didn’t know, on my way to the 1st Recruit Training Battalion at Kapooka, near Wagga, in southern New South Wales. I was looking forward to starting my career and earning some money. The army recruiters had been friendly and supportive, and there were a few of them travelling with us.

There was a relaxed feel about the trip. We stopped at a roadhouse on the way to Kapooka and got some lunch, and everyone was in good spirits. The countryside was mostly wide open grazing lands covered with short, yellow-brown grass; very different from the rolling emerald-green hills of the south coast where I’d spent most of my life. The coast gets decent rainfall and it’s good dairy country, but out here in the inland, it was dry, tough country. I’d never really been away from home, and my senses were a bit overwhelmed.

It was about six in the evening by the time we reached Kapooka. When the bus stopped, the driver opened the door and a group of MPs – military police – in bright red berets got on board. It was as if someone had just flipped a switch on my life.

‘GET OFF THE BUS!’

We all looked at each other, and a couple of the guys smirked at the screamed command.

‘I SAID, GET OFF THIS FUCKING BUS NOW AND FALL IN OUTSIDE. MOVE IT!’

We suddenly all knew this was for real, and bumped into each other as we got out of our seats and pushed our way to the door.

‘NO FUCKING TALKING. GET OFF THE BUS. GET YOUR SHIT AND LINE UP OUTSIDE!’

Talk about a reality check! Once we’d had our names marked off, we didn’t stop running. Over the next few days we were issued with uniforms and a pile of other gear including a pack, webbing pouches and belt and harness, water bottles, boots, mess tins, hats, raincoats, sheets, blankets, towels and even a toothbrush. We were given everything we’d need to start our lives all over again. It was May, and although it wasn’t yet winter, that place was cold. Anyone who’s been to that part of Australia knows how bitter it can be when the chilled wind whips across those empty plains and you wake to find the grass white with frost. It was extreme – freezing in winter and baking, stinking hot in summer. I would discover there was nothing that could remotely be described as mild about the place or the experience.

‘HALLWAY TWENTY-SIX, WAKEY, WAKEY. OUTSIDE!’

Had I even slept? The next morning, it seemed like I’d had my eyes closed for ten minutes when our section commander was screaming at us to wake up. ‘GET OUT HERE AND BRING YOUR SHEET WITH YOU, OVER YOUR SHOULDER!’

Screaming, screaming, screaming. Bombardier Wilson was an absolute arsehole. It was the section commander’s job to get in our faces and tip our civilian world upside down, and Wilson seemed to love his job.

We were sleeping four to a room, and had to parade in the hallway with our top sheets over our shoulders to make sure that each of us had pulled his bed apart. In the past, some smart arses had tried to take a short cut by making their beds perfectly and then sleeping on top of the blankets so they could save a few precious minutes of morning routine, but the instructors knew all the short cuts in the book.

Wilson went on at us from the moment we woke to the moment we passed out in the evenings. He’d follow us into the bathroom to make sure we were shaving. It was rush, rush, rush all the time, and guys would have bits of toilet paper sticking to their faces where they’d cut themselves. I was seventeen and had barely started shaving, but still had to go through the motions. Mates of mine back home were in school, sneaking drinks and cigarettes, surfing or playing footy, but I was a teenager who had to iron his fucking pyjamas, on pain of punishment.

Everything had to be perfect.

Sheets had to be pulled tight and tucked in with hospital corners. The stripes on the scratchy, red-brown blankets had to run right down the centre of the beds, and sheets had to be turned over at the top precisely the length of a rifle bayonet. Everything we owned had to be kept in its designated place. Uniforms had to be ironed and hung facing the same way, and our civilian clothes were locked away so that there were no reminders of the lives we’d left behind. Socks had to be folded just-so, and there were rules about how far each item of clothing or belt buckle or toothbrush could be from the next.

Nights were filled with the smell of Brasso and spray starch, as we strove to get our uniforms in a state fit for the following morning’s inspection. Minor infractions were punished with screams of abuse and the violent ransacking of whatever had been done incorrectly. Blankets and sheets were ripped from beds and tossed out the barracks first-floor window to land in the dirt and grass below. If Bombardier Wilson found a water bottle a few millimetres out of place in a locker, he would reach in and slide everything onto the floor, and the hapless recruit would have to start all over again.

There was no free time. The army owned us, body and soul, and every minute of every day was filled with some sort of activity. We’d run in the morning, our cheeks and noses, bare arms and legs stinging from the cold, our breath freezing in front of our faces. Panting, gasping, sometimes throwing up, we realised how easy our lives at home had been. Having played rugby helped me a bit, but they were pushing my young body to its limits, and beyond. During crisp, cool days under empty blue skies, we drilled and marched, learning to walk all over again, as though we were toddlers. Always there was the yelling, the abuse, and the bombardier’s nose almost touching yours as he delivered each day’s fresh insult, punctuated with tiny drips of spittle.

‘CLOSE YOUR FIST WHEN YOU MARCH OR I’LL STICK MY COCK IN IT, BRYANT!’

‘EYES FRONT OR I’LL RIP THEM OUT AND SKULL-FUCK YOU TO DEATH, YOU STUPID BASTARD!’

‘SWING THOSE FUCKING ARMS BREAST-POCKET HIGH WHEN YOU MARCH, OR I’LL RIP THEM OFF, STICK THEM IN YOUR EARS AND RIDE YOU AROUND THE PARADE GROUND LIKE YOU’RE A FUCKING HONDA!’

Breakfast, lunch and dinner became our only respite. I looked forward to meals and shovelled the food into me. Our bodies had become machines and our brains weren’t far behind.

When we weren’t marching or drilling, our foggy minds were being filled with map reading, military law, first aid or radio procedures. A few of the guys were excited at the prospect of the weapons lessons but there were weeks of training before anyone pulled a trigger. During the lessons, the bombardier didn’t scream, but he was no more tolerant of mistakes, especially safety breaches. Still, there was at least a feeling the instructor was genuinely trying to teach you something, rather than just hoping you’d remember it through constant ranting, belittlement and abuse.

As we recruits grew more confident and started getting into the groove of life at Kapooka, we could laugh and joke in private about some of the things the instructors did. There was a dark side to that barren, windswept, soulless place as well, though.

I’ve got mates who are still in the army who have been posted to Kapooka to be instructors and they tell me that, these days, recruits are issued with cards that they can hold up to instructors to let them know when they’ve had enough of their bullying and abuse. That sounds extreme to someone like me who survived the old system, but we did have some serious problems. Two recruits went absent without leave during my time at Kapooka. One jumped a train and was so exhausted that he fell asleep and rolled off and injured himself. The other guy made it to Melbourne, where he hanged himself in a public toilet.

Things often went too far, as with the recruit who had pissed himself rather than move from his spot in the corridor. I understand that they’re trying to break you down and then rebuild you, but things had to change at Kapooka and, apparently, they have. Although I didn’t know it at the time, and neither did the army, I’d joined the Australian Defence Force at what was probably a turning point.

Our uniforms back then were the same plain green heavy cotton ones that troops had been wearing, pretty much unchanged, since the end of World War II. They had to be starched and ironed with razor-sharp creases and our black leather boots had to be spit polished, which took hours. Our rifles were the big, old 7.62- millimetre self-loading rifle (the SLR) and the F1 sub-machine gun, which dated from the late 1950s and early ’60s. Back then, in 1989, Australian soldiers hadn’t been to war since Vietnam in the ’60s and ’70s. Our training methods, including the virtually unchecked abuse our instructors meted out, belonged to another era.

Within a few years, the army would switch to polyester-blend camouflage uniforms that didn’t need ironing; to a lighter, smaller calibre rifle, the 5.56-millimetre F88 Steyr; and would be serving in modern peacekeeping operations in places such as Rwanda and Somalia, where knowing who was your friend and who was your enemy was even more confusing than in Vietnam. By the turn of the 21st century, the army would be fighting an enemy different from any we’d ever encountered, in the deserts and mountains of Afghanistan and Iraq.

*

Failure was never an option for me – I hate the thought of letting myself down. I set myself small goals in order to keep my sanity and make it through Kapooka. At seventeen I was the youngest recruit in the platoon, but could see that men who were older than me were finding the hard slog of training just as difficult as I was. This inspired me, because I wanted to prove to everyone, especially myself, that I could pass this tough course at my age.

As we progressed, we’d be given rewards, like we were dogs in training, and the smallest thing could mean so much. The first time I got to leave the base was like a dream. We were allowed to go into Wagga, and, while we were forbidden to drink alcohol, we could wander around the shops, have a soft drink, look at girls who weren’t wearing baggy, unflattering green skins and, most importantly, not be in Kapooka. Later, even though I was still seventeen, I was allowed with the other recruits to start having a few beers in the boozer, the canteen on base.

During the days, we spent increasing time on the range, zeroing and trying to qualify with our SLRs. We also got to fire a heavy-barrelled automatic version of the SLR, called the AR. I’d only ever fired a .22 rifle before joining up and, even after my training at Kapooka, I was never a fantastic shot. As it’s turned out, I’ve carried a firearm for work most of my adult life, although, unlike some of the Americans I’ve served with in Afghanistan, I’m not a gun freak. Weapons are a tool of the job to me; nothing more.

Like a lot of people on the course, the only thing I enjoyed about basic training was the march-out parade at the end of it. I really felt as though I’d achieved something. Halfway though our course, Bombardier Wilson had broken his leg playing rugby and had been replaced by a medic corporal, who was about as different from the abusive artilleryman as he could be. Wilson came back to Kapooka to have a beer with us the day we graduated and, despite all the ill-treatment we’d been through, we were happy to have a drink with him – as soldiers, rather than his scared, white-faced recruits.

About three years after recruit training, I was playing rugby at Holsworthy in south-western Sydney, where I was based, and when the other team ran on to the field, I saw Bombardier Wilson among them. He grinned at me in recognition and I nodded back at him. That day, I didn’t care whether our team won or lost; I spent the whole game chasing him around the field.

It was payback time, and when I caught up with him, I smashed him.

I thought for a while about applying to be an army medic or physical training instructor, but ever since I’d seen the picture of the army dog handler in the corridor at Kapooka, I’d been sure what I wanted to do. As it happened, I was posted to the Royal Australian Engineers, the corps that controls the army’s explosive sniffer dogs.

There was something about dogs, and working with them, that really appealed to me. I like a dog’s companionship – it gives me a sense of fulfilment and peacefulness, like the feeling some people get sitting on a beach watching waves roll in. Dogs really are loyal to the last beat of their heart. Nothing’s simple in the army, though, and it was four years before I could actually do a dog handler’s course.

When I finished at Kapooka, I was sent, with the rank of sapper, to the School of Military Engineering at Holsworthy to learn how to be a combat field engineer during my initial employment training. Engineer training was interesting, with the course covering a whole heap of subjects, including building bridges, water purification, clearing land mines and booby traps, small boat handling, demolitions, and rope work. It was good to be learning new things, as opposed to marching and being screamed at. We got weekends off, and I’d go home to Dapto to see my girlfriend, Jane. I’d first met Jane two weeks before leaving for Kapooka. She was fifteen at the time, a friend of a friend and she worked in the McDonald’s at Albion Park Rail, near where I lived.

After I finished training, I was sent to 1 Field Engineer Squadron at Holsworthy, where I screwed up, big-time, very early on. I was on guard duty at the front gate and one morning I managed to sleep in because an overnight blackout had cut the power to my alarm clock. There was no sympathy, though, and I was given two weeks’ restriction of privileges. I was charged and fined, and spent a lot of time doing drill, cleaning garbage bins, sweeping roads and cutting hedges, working until ten o’clock most nights. It was a good lesson for a young digger to learn – that people depend on you doing your job and there’s no excuse for failure.

Even when I was I was on restriction of privileges and being punished, I was still army-mad. I thought I’d like to try out for the SAS selection course, and asked the sergeant of the guard if I could start running with a full pack and webbing during my punishment period. He told me I was too young even to apply for the SAS, that I should wait until I was 21 and had more experience, but I persisted and he gave me the OK. He probably thought I was crazy, and I think some of the other people on base thought the sergeant was beasting me by making me run with my pack on.

After my punishment was finished, I had enough on my plate without training for the SAS in my spare time, and it increasingly looked like Jane and I were going to settle down together. I did an army driver’s course, and when I was posted to 1 Field’s airborne troop, I was sent to the Parachute Training School at Nowra, near where I’d grown up on the south coast. The first few jumps, in particular, were exhilarating and, unlike Kapooka, we were able to get pissed every night.

Not every aspect of the army, I was learning, had to be as full-on as Kapooka. The parachute course was intense, and everyone was focused on learning the flight and emergency drills, but there was still time for some humour. One day, everyone on the course was sitting in the big timber-panelled lecture room, paying attention to the instructor. As he was talking, the door behind him opened softly and another instructor, totally naked except for a paper bag over his head with eye holes cut out of it, snuck in, padded silently along the stage behind the lecturer, then slipped out another door. As hard as we tried, some of us couldn’t help laughing. The instructor wanted to know what was so funny, but no-one said a thing. He looked behind him and saw nothing. As soon as he returned to his lecture notes and continued speaking, the naked phantom -reappeared, and darted behind him and out the first door.

While the parachute course was fun, I wasn’t getting any closer to my dream of working with dogs. There was only one military dog handler’s course per year and I always seemed to miss it. However, in the airborne troop we also learned how to do hand searches for bombs and would often work with the dog teams, both in training and in real-life searches for bombs and explosives with the police and other civil authorities.

I really enjoyed watching dogs and their handlers working together as a team, especially when the handler would let the dog off its lead to do its job. The dogs always seemed so eager to please their partners, and responded to every command as though they were perfectly attuned to them. I was fascinated by how a handler would position himself to channel a dog into searching different areas, and the way he would anticipate the dog’s every move and read its body language. There was understanding, respect and friendship there. I knew that I always felt better with a dog by my side, so how much better could life get if I were paid to work with dogs like these guys did?The longer I had to wait to get on the dog handler’s course, the keener I became.

The work of searching, in training and for real, continued. When the former President of the United States, George Bush Snr, came to Australia on a state visit, the airborne troop was part of the team tasked with searching his hotel room and other venues he’d be in. We prided ourselves on our professionalism, although when one of our guys, Wrighty, was searching with a small hand mirror inside a fuse box at the Maritime Museum in Sydney, he did manage to black out a whole section of the building by short-circuiting something.

There was a huge bang, like an explosion which, given the job we were doing, startled everyone. We went to see what had happened and Wrighty was just standing there, stunned. His hair was sticking out – he looked like the boxing promoter Don King – and his eyebrows had disappeared. The glass had blown out of his hand mirror and the metal was all buckled.

One of my mates, Chris Arp, went up to Wrighty to check him out. ‘How are you not dead?’ Chris asked in amazement.

‘I don’t know.’ Wrighty said. ‘I should be dead.’ He’s still got that mirror, to this day, as a souvenir.

The president’s Secret Service detail was also checking places, but they weren’t keeping too close an eye on their own vehicles, because one of my mates, Wainy, managed to nick one of their numberplates, which we proudly displayed in the unit boozer.

The dog teams searched the president’s hotel room first, and then we went in to do a second, detailed, check, following the dogs so that our scents didn’t confuse them. We used mirrors to check in hard to see places, methodically searching from left to right, and from the lowest to the highest parts of the room.

‘So, this is George’s room?’ Wainy said as we searched the hotel suite.

‘That’s what the intel said.’ Wainy looked at me, and I smiled and nodded. We knew this was a once-in-a lifetime opportunity that we couldn’t pass up. At the time, Jane and I had a favourite practical joke that we liked playing when friends stayed at our place, or when we went visiting. I told the other guys about it and they thought it would make for a fitting welcome for the US President. One of them ducked outside and kept watch for Secret Service dudes while the rest of us quickly went to work.

I’d like to think that George and Barbara Bush saw the brighter side, after a long day of public engagements, of trying to climb into a king size bed that had been short-sheeted by some Aussie soldiers.

TWO

Ziggy

1994

Finally, in February 1994, after more than four years’ wait, I was able to get into an Explosive Detection Dog Handler’s course at the School of Military Engineering.

I’d come a fair way since joining the army as a seventeen-year-old. Jane and I had married in 1992, and while I’d been waiting to go on the handler’s course, I’d already done my two promotion courses to become a corporal and had been promoted to lance corporal. The other five students on the dog handler’s course were all sappers.

If I had wanted to pursue higher rank in the army, I wouldn’t have gone on the dog handler’s course. At the time there was only one sergeant dog handler’s position in the Australian Army, so, until he retired or died, there was no prospect of me even going higher than being a corporal, which was the next rung on the promotion ladder. All up, there were probably less than 20 military dog handlers in Australia at the time. However, rather than lessening, my determination to work with explosive sniffer dogs had grown stronger over the years I’d been around them as a field engineer and in the hand-search role.