28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

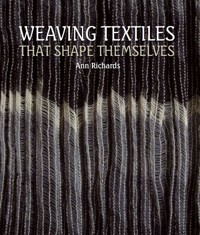

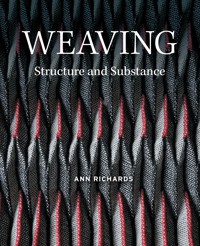

Weaving: Structure and Substance looks at weave design from several different perspectives, showing how resources, ideas and practical experience can come together in a creative process of designing through making. Emphasizing the potential of woven textiles throughout, Ann Richards follows the success of her sister title Weaving Textiles that Shape Themselves and explores the tactile properties that emerge from the interaction of material and structure. The book is organized into four parts that look at the natural world as inspiration, the design resources of material and weave structure, the fabric qualities as starting points for design, and the practical issues of designing through making. With over 280 lavish photos, this book will be an invaluable resource for textile designers and enthusiasts looking for inspiration and practical advice.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

WEAVING

Structure and Substance

Self-folding origami neckpieces. Silk, steel and paper.

WEAVING

Structure and Substance

ANN RICHARDS

First published in 2021 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2021

© Ann Richards 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 930 3

Cover design: Peggy & Co. Design

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction:The Interplay of Material and Structure

Part 1 Nature as Designer

1 Endless Forms Most Beautiful

Part 2 Resources for Design

2 Material Resources: Fibres and Yarns

3 Structural Resources: Simple Gifts

4 Structural Resources: Beyond Plain Weave

Part 3 Designing for Fabric Qualities

5 Fold Here

6 Light Work

7 Both Sides Now

8 Off the Grid

Part 4 Designing Through Making

9 From Sample to Full-Scale Fabric

10 Reflective Practice and the Butterfly Effect

Bibliography

Online Resources

Suppliers

Index

Acknowledgements

I have to begin on a sad note because five people who have given me a great deal of help and encouragement have died since the publication of my first book. Margaret Bide accepted me as a student at West Surrey College of Art and Design, so changing the direction of my life, and she later worked hard to ensure a continuing supply of high-twist woollen merino yarn – it is used for many samples in this book. Deryn O’Connor and Amelia Uden, who were my stimulating tutors at college, later became good friends and were always supportive and encouraging. Amelia generously gave me a sample of her design in Russian cords, which I have included in this book. Susi Dunsmore worked for many years with the weavers of Nepal, promoting their textiles, particularly those made of ‘allo’, and holding wonderful ‘Nettle Days’ that will be greatly missed by many of us. A final loss is the Japanese designer Junichi Arai, co-founder of Nuno, an important influence on my work, especially in the use of high-twist yarns. I shall continue to miss all these people who were inspirational, encouraging and full of an infectious enthusiasm for textiles.

I would like to thank the many designers and artists whose work is included here: Paulette Adam, Lotte Dalgaard, Alison Ellen, Mariana Eriksson, Berthe Forchhammer, Stacey Harvey-Brown, Denise Kovnat, Gilian Little, Noriko Matsumoto, Andreas Möller, Wendy Morris, Anna Nørgaard, Tim Parry-Williams, Geraldine St Aubyn Hubbard, Reiko Sudo, Ann Sutton, Rezia Wahid, Margrit Waldron, Angus Williams and Deirdre Wood. A special thank you to Wendy Morris for not only allowing me to use examples of her work but also reading the text and making valuable suggestions. I am also grateful to those designers who I am unable to acknowledge individually because they are unknown to me – I have collected many fabrics over the years, and some of these were not attributed to a named designer. They range from simple tea towels to elegant scarves, but all are pieces that I picked up because I knew them to be useful and believed them to be beautiful.

Many thanks to Greta Bertram of the Crafts Study Centre for her help in obtaining photographs of work in the collection and to Martin Conlan and Gina Corrigan for photographs of textiles by the Miao people. I would also like to thank two archaeologists. Noortje Kramer introduced me to the remarkable Rippenköper textiles and commissioned me to attempt to replicate their effect, a fascinating process that has also fed into my own work. Johanna Banck-Burgess was responsible for the analysis of the original textile fragment that I worked from and generously allowed me to include her photograph.

The photographs have been taken by the designers and artists themselves, and by: Ole Akhøj, Johanna Banck-Burgess, Alan Costall, Sanne Krogh, Håkan Lovallius, Joe Low, Loucia Manopoulou, Colin Mills, James Newell, Takao Oya, Karl Ravn, and David Westwood. Textiles and photographs not otherwise attributed are by the author.

While writing this book I have had ongoing encouragement from my friends and collaborators in the exhibition Soft Engineering: Textiles Taking Shape: Alison Ellen, Julie Hedges and Deirdre Wood. I hope we will be working together again soon.

And a final thanks to Alan for support and advice, especially with photography.

INTRODUCTION

The Interplay of Material and Structure

Although structure is all-important, the physical characteristic of an object is naturally also influenced by the material used in its making. The resulting interaction between material and structure is an absorbing study; for sometimes the material is dominant – compare a silk sari with a wooden fencing panel, both interlaced in plain weave – and sometimes the structure is dominant – compare a felted piano hammer with a knitted Shetland shawl, both made from wool fibre.

Peter Collingwood, Textile and Weaving Structures

Of the many features characteristic of woven textiles, the aspects that probably attract the most immediate attention are colour and pattern. But underpinning these obvious features, textiles necessarily possess textural qualities and deeper tactile properties – they have substance. Such aspects often receive less attention than they deserve, even though all weavers know that they are essential to the success of woven fabrics. So, although colour and pattern will feature in this book, there will be particular emphasis on the ways that tactile properties emerge from the interaction of material and structure.

Weave structure is crucial to the design of woven textiles but, being simply a plan of interlacement, it does not in itself specify what a fabric will be like. It remains an abstraction until embodied in a fabric, since fibre, yarn structure, sett, scale and finishing techniques can create so many different results. Peter Collingwood draws attention to this issue when he invites us to ‘compare a silk sari with a wooden fencing panel, both interlaced in plain weave.’

Recently, the ease of computer drafting has encouraged some designers to become absorbed in complex manipulations of structure, using programs that generate new weaves. It has even been suggested that, from the multitude of structures that result, the ‘successful’ weaves could be woven as a physical record of these particular ‘weave species’. But this begs the question of how any interlacements are to be judged as successes when none have been tested as real objects.

Rather than seeing weave drafts on paper (or screen) as inherently ‘successful’, it is probably more reasonable to think of them as looking promising or having potential for particular purposes, with ultimate success or failure depending on their interplay with the material. For example, plain weave is potentially the firmest structure but nevertheless not all plain weave fabrics are firm, as this quality will vary with the texture and stiffness of the fibre, the character of the yarn and the sett. Collingwood’s comparison of the silk sari and the wooden fence deliberately captures extremes of possibility in terms of fineness, stiffness and lustre of material.

More complex weaves can be thought of as having promise for particular uses on account of their characteristic styles of interlacing or length and placement of floats. But since long floats tend to allow substantial changes, through yarns sliding over one another, pulling on other threads or shrinking, the structures as weave drafts may bear little resemblance to the finished fabric. Once again, their success will depend on their interplay with the material.

When initiating a design, a common approach is to draw on the long tradition of woven textiles by exploring the possibilities of a well-known structure, a material or a particular combination of the two. But an equally valid starting point can be some outside source of ideas or perhaps a desired fabric quality. In practice, it is often necessary to move between these different strategies as the fabric takes shape in a process of reflective design. Anni Albers gives the example of a fabric intended for the walls of a museum, where there is a focus on the desired functional characteristics of the fabric, but with constant references back to the constraints of material and structure. At the end of this problem-solving process of moving between practical requirements and the possibilities of material and structure, she concludes: ‘Here, now, we have a fabric that largely answers the outlined requirements. It formed itself, actually…’

A pleated dress twisted into a skein for storage. This flexible tube of self-pleated fabric makes a simple garment that moulds itself to the body, but other weave structures can create fabrics that transform themselves into shaped pieces for more complex ‘loom-to-body’ garments.

This book is arranged in four parts, looking at weave design from different viewpoints. It begins with the idea of nature as designer, because interesting parallels have been drawn both by designers and biologists between evolution and design. The following section deals with resources and the ways that materials and weave structure can serve as starting points for design, while the third part considers design from an alternative viewpoint of aiming for desired qualities of cloth, considering various possible solutions. Moving between these different approaches will often be the best way to resolve a design, so there is a good deal of cross-referencing between chapters – a book is necessarily sequential but designing is more like a network. At every stage a responsive attitude is helpful, allowing unexpected results or chance occurrences to become starting points for new designs, so the final part of the book considers the practicalities of designing through making, emphasizing the need to be a reflective practitioner.

This detail of a skirt shows how a piece of fabric woven in a combination of double cloth and 1/3 twill can shape itself during wet finishing. The complete skirt is shown in Chapter 8.

One important aspect of textiles is the tremendous range of functions that they can fulfil, from the mundanely practical to the highly decorative and beautiful. As a student, and later a tutor, at the Surrey Institute of Art and Design (now the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham), I was struck by how this range was reflected in the college’s textile collection. There were stunningly beautiful and valuable pieces in richly coloured silks but also very down-to-earth, everyday textiles, such as towels, and even a baby’s nappy – a member of staff noticed that the nappies she was using for her baby were interchanging double cloths, so donated one to the collection! In this spirit my selection of textile examples spans a wide range and celebrates not only the obviously striking or unusual but also humble everyday pieces of cloth. For a weaver, these too have their beauty.

PART 1

Nature as Designer

Whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.

Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species

The water lily Victoria regia (now Victoria amazonia). This is something of a design icon as the ribbing on the underside of the leaf is reputed to have inspired the roof structure of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, though this is probably a myth. The leaf does however provide a good example of nature’s ability to produce an effective structure with great economy of material, offering a useful lesson to designers in all fields. (Photo: Alan Costall)

Interesting parallels have been drawn, both by designers and biologists, between evolution and design, with each side seeing lessons for their own practice and taking ideas from the other. For example, fabric shear has been informative to biologists investigating worm biology while, working in the other direction, natural forms provide a familiar source of ideas for designers in all media. In textiles such inspiration most often concerns pattern and colour, but textile designers can usefully draw lessons from practitioners in other fields, such as architecture, where greater attention is paid to the deeper structures and growth processes of nature, since these can be highly instructive in shaping the form and functioning of textiles. This approach can be most clearly seen in the various high-tech fabrics that have been developed through biomimetic research, but it can equally well be applied to the structure and substance of textiles designed for more everyday purposes. Some of the lessons from natural forms that are discussed in this part of the book will be picked up later in a series of chapters concerned with designing for specific fabric qualities.

CHAPTER 1

Endless Forms Most Beautiful

Design in nature is hedged in by limitations of the severest kind… On the other hand, complexity in itself does not appear to be expensive in nature, and her prototype testing is conducted on such a lavish scale that every refinement can be tried.

Michael French, Invention and Evolution

Over the last century and a half interesting parallels have been drawn, both by designers and biologists, between evolution and design, and this has definitely been a two-way street, with each side seeing lessons for their own practice and taking ideas from the other. In the introduction to their book Mechanical Design in Organisms, the zoologist S. A. Wainwright and his colleagues explain their use of the term ‘design’:

The idea that biological materials and structures have function implies that they are ‘designed’; hence the book’s title. We run into deep philosophical waters here, and we can do little but give a commonsense idea of what we mean. In our view structures can be said to be designed because they are adapted for particular functions… The designing is performed, of course, by natural selection.

Writing elsewhere, Wainwright has suggested that the science of biomechanics would benefit from developing a concept of ‘workmanship’, while E. J. Gordon, in his book Structures, describes how the fabric shear produced by cutting garments on the bias of a woven fabric has proved inspirational to biologists investigating worm biology. As an aside, he mentions that he has himself used the bias cut as a source of ideas for the construction of rockets, an interesting example where the ‘soft’ engineering of textiles has been inspirational to the ‘hard’ engineers!

Robin Wootton, researching the folding of insect wings, makes extensive use of paper models to investigate the mechanisms involved and remarks on the many connections to be found with other disciplines:

When we began research on insect wing folding, we quickly discovered that the mechanisms we were identifying also occur in many other kinds of folding structures; and we found that we were talking with engineers, origami masters, mathematicians and the designers of pop-up books… in nature, similar mechanisms can be identified in the expanding leaves of hornbeams and in the respiratory air-sacs of hawkmoths.

Robin Wootton, How do insects fold and unfold their wings?

Structures such as the hornbeam leaf and the hawkmoth air-sac provide examples of a kind of ‘natural origami’ that has been widely discussed by engineers concerned with deployable structures – compact forms that can be unfolded and refolded with ease. Robin Wootton describes a number of these interesting objects, ranging from folding maps to expanding solar panels for satellites in space, before finally concluding ‘But the beetles and earwigs got there first.’

The reference to expanding solar panels concerns the fold called Miura-ori, named after the Japanese engineer Koryo Miura. Though his ultimate aim was to design deployable structures for use in space, Miura used the problems of folding and unfolding maps as a way to explore basic principles of packing flat sheets into small packages. The V-shaped fold that he worked with was already known in origami but Miura investigated the effect of using different angles on the ease of folding and unfolding and on the size of the folded package. He found that with a large angle there are limits to how small the folded package can be made, but with an angle of only 1 degree there are difficulties in folding and unfolding. He concluded that for easy folding into a very small package angles of 2–6 degrees are optimum, creating a sheet that can be unfolded in a single movement simply by pulling on two diagonally opposed corners. Most instructions currently available for constructing the Miura fold suggest an angle of 6 degrees (seeOnline Resources).

The Miura-ori structure shown open and partially closed. The structure can be folded completely flat in a single movement by pushing on opposing corners of the sheet.

Raspberry leaves, showing the compact folded leaf and some fully open leaves.

Ha-ori (leaf fold) shown closed and open.

The designer Biruta Kresling noticed that a similar problem of packing a large sheet into a small space occurs with the hornbeam leaf, because the bud is both shorter and narrower than the leaf that will emerge. As the leaves have a pleated structure she wondered whether the V-folds that Miura had investigated could model the process of opening and expanding that occurs when the leaf emerges from the bud. This proved to be the case and she produced the fold known as Ha-ori (‘leaf fold’), which nicely models both the lengthening and broadening of the opening leaf (Peter Forbes gives good instructions for constructing this fold). Leaves on various other plants, such as the raspberry, show similar unfolding and such examples of ‘natural origami’, together with the origami tradition itself, are very instructive when it comes to designing self-folding textiles with origami-like effects. Paper folding is a good way to experiment with the possibilities when planning a design and exploring the impact of different V-fold angles on the overall form of the piece (more detail is given in Chapter 5).

INSPIRATION FROM NATURE

Such cases of ‘natural origami’ provide good examples of nature’s ability to get there first, giving some explanation of why natural forms and processes provide inspiration for designers in all media. Architects seem particularly conspicuous in this respect, partly because of the scale on which they work. For example, it is frequently suggested that Joseph Paxton was inspired by the leaf of the water lily Victoria regia in designing the roof of the Crystal Palace, though it seems unlikely that there was a direct connection.

The water lily Victoria regia, showing the longitudinal and cross-ribbed underside of the leaf.

Paxton certainly does appear to have been impressed with the ‘engineering’ of the ribbed structure of the leaf, having posed his eight-year old daughter on one to demonstrate its strength, but the ribbing is only modestly three-dimensional, while the most notable feature of the roof of the Crystal Palace was the deeply folded ridge-and-furrow system, which had already been invented by John Loudon. Heinrich Hertel notes that this ridged structure closely resembles the pleated structure of an insect wing, though he refers also to the popular story about Paxton and the water lily.

The roof structure of Sir Joseph Paxton’s gigantic steel and glass exhibition hall, the London Crystal Palace, bears an amazing similarity to the lattice-work and articulation of the dragonfly’s wing… Paxton said he conceived this extremely fine-membered structure in his youth, as a gardener, by studying the leaf skeleton of the tropical water lily Victoria regia.

Heinrich Hertel, Structure, Form, Movement

A section of the dragonfly wing. (After Hertel)

This cross section shows the pleated structure of the leading edge of the wing. (After Hertel)

A deeply folded structure provides extra stiffness as compared with a less three-dimensional ribbed surface such as the lily leaf and the roof of the Crystal Palace certainly did resemble an insect wing. There is no evidence that the dragonfly was a direct source of inspiration for the ridge-and-furrow system, but it seems a particularly accurate analogy because the folds in the dragonfly wing are not deployable pleats – the wings are rigid structures that cannot be folded up and the function of the pleating is to provide stiffness. I have myself used the dragonfly wing as a source of ideas for pleated scarves to deal with some similar issues to those of glasshouses – a desire to combine translucency with strength and stiffness. My requirements were not exactly the same, given that I wanted deployable pleating, but stiffness was still an issue as my delicate pleats were tending to buckle and collapse. Fortunately the structure of the dragonfly wing combines longitudinal ribs with many finer cross-bars that act as ‘struts’ to support the pleating, a strategy I gratefully adopted.

Detail of a pleated fabric. Warp: Linen. Weft: Crepe silk and hard silk, with picks of linen at intervals serving as ‘struts’ to stiffen the pleating.

The ribs and cross-bars in the dragonfly wing are particularly conspicuous, but similar structures can be seen in the many insects that are able to fold their wings when not in flight, though such ribbing is often more delicate in wings that are protected when not in use. In insects such as grasshoppers and beetles the pleated rear wings that are used for flying can be folded away under hard fore wings – in the example shown here it is clear that when it comes to the process of imitating nature, this is another case of nature getting there first!

Many insects of the grasshopper family are able to conceal themselves by folding away their delicate pleated flying wings under protective fore wings that imitate leaves. (Photo: Alan Costall)

The design of many modern buildings can clearly be seen as making references to natural forms, and this theme was beautifully explored in the exhibition Zoomorphic at the Victoria and Albert Museum, together with an accompanying publication by Hugh Aldersey-Williams. One of the most prominent architects working in this way was Frei Otto who based designs on various structures such as crab shells, the skulls of birds, spider webs and bubbles. It is clear in many of these designs that architects have learnt from nature in achieving strong structures with great economy of materials, as thin shells or sheets of fabric are supported and stiffened through strategically placed ribs, struts or tension cables. It is easy for weave designers to feel that such concerns are not so pressing in textiles as they are in architecture, but similar structural issues of strength, stiffness and so on do still arise on this smaller scale, particularly with fabrics that have a strong three-dimensional character, so natural forms offer lessons in terms of substance and performance as well as in the appearance of the cloth.

BIOMIMETIC TEXTILES

Good examples of learning from nature can be seen in the many biomimetic investigations that have led to designs for high-performance textiles. Veronika Kapsali describes many of these innovative textiles in her book on biomimetics, including a fabric for sportswear that imitates the transpiration of plant leaves, Stomatex, and the swimsuit fabric FastSkin based on the structure of sharkskin.

Studies at the Centre for Biomimetics at Reading University on the opening and closing of pine cones in dry and damp conditions inspired the design of an adaptive fabric that responds to moisture. Colin Dawson, who carried out this work, discovered that the scales of the pine cone are composed of two different types of wood cell, and that although these both absorb water they have very different swelling properties. These different responses cause the scales to open out or close up according to the atmospheric conditions. Dawson applied this to textiles by bonding a synthetic woven fabric to a non-porous membrane and cutting U-shaped perforations that formed flaps that would open or close in response to changes in the moisture in the air.

Like the cells in wood, the various textile fibres have different properties and do not all swell to the same extent when wetted out. Natural fibres swell considerably when they absorb water and this is the basis for textured effects that are created by the creping reaction (which will be explained in Chapter 2). In contrast most synthetics swell relatively little, so many further designs on the principle of the pine cone might be possible with various combinations of natural and synthetic fibres in backed or double cloths.

Veronika Kapsali followed up Dawson’s work on the pine cone to produce a self-regulating fibre INOTEX. This takes an unusual approach because, unlike the fibres in traditional crepe yarns that swell and make the yarn thicker, INOTEX fibres are engineered to become thinner as they absorb moisture, making a textile that is more permeable and so more comfortable to wear over a range of different conditions.

Birds’ feathers often combine both pigments and structural colours as in this jay feather where brown pigments lie alongside the brilliant blue produced by the fine structure of the feather.

Another interesting development is Morphotex, a yarn that imitates the structural colours seen in nature, for example in the feathers of some birds and perhaps most strikingly in the wings of the brilliant blue Morpho butterfly. Such colours do not rely on pigments but are produced by interference effects when light is reflected from microscopic layered structures in scales, feathers or shells. The Morphotex yarn produced so far, though attractively iridescent, is nowhere near as intensely coloured as the butterflies it imitates and this exemplifies one of the great difficulties in biomimicry. In many cases, not only has nature got there first but, as a result of the lavish prototype testing of natural selection, does it much better. While Morphotex yarn uses sixty-one alternating layers of polyester and nylon to produce a pale, iridescent effect, the Morpho butterfly needs only ten layers of chitin with air spaces in between to create its extraordinary brilliant colour. However, this particular biomimetic design aims to use structural colours as a substitute for more environmentally damaging dyes, which seems a worthwhile strategy to pursue. Peter Forbes points out that the problem in the case of Morphotex is insufficient contrast between nylon and polyester, so ‘If two cheap high-contrast fibre materials could be found, some dazzling textiles would result’ (seeBibliography).

ECONOMY IN NATURE

As described above, the water lily leaf and dragonfly wing, together with the crab shells and birds’ skulls that so inspired Frei Otto, are all efficient structures in which strength and stiffness are achieved with minimal material. Julian Vincent, formerly head of the Centre for Biomimetics at Reading University, sums up this characteristic of many natural structures with the phrase ‘In nature materials are expensive and shape is cheap’ and emphasizes the increasing need for human designers to work in a similar way to avoid a wasteful use of limited resources:

Most of our resources, especially materials, are treated by economics as if the supply were infinite, when demonstrably it is not for those that are non-renewable. In his engineering, use of materials and energy, man lets design take second place, whereas nature treats materials as expensive and designs with apparent care and attention to detail. This results in durable materials and cheap structures that are easy to recycle under ambient conditions.

Julian Vincent, ‘Survival of the Cheapest’ (seeOnline Resources)

In textiles, attempts to economize on materials often focus on substituting inferior materials, particularly where it is assumed that they will not be too noticeable. For example the term ‘backed cloth’, often used for fabrics with a supplementary warp or weft, derives from the industrial system of using inferior materials for yarns that will not be seen on the back of the cloth. Stacey Harvey-Brown describes the widespread use of this practice in the industrial production of matelassé fabrics, but comments that as a handweaver she would prefer not to use inferior materials in this way. The solution, as Julian Vincent suggests, is to accept that materials are expensive and to design with the care and attention necessary to use them to best advantage.

NATURAL FORMS AND TEXTILE QUALITIES

Although the visual qualities of natural objects suggest many ideas for colour and pattern in textiles, the development of high-tech biomimetic fabrics shows the value of considering the deeper structures and growth processes of nature as a source of ideas. This approach can equally well be applied to the structure and substance of textiles designed for more everyday purposes. It will often be found that even a single object may have multiple ideas to suggest and this feeds particularly well into textile design since fabrics inevitably have multiple qualities. It is worth examining natural objects closely and on many scales – inexpensive but effective digital microscopes are now readily available and can reveal beautiful details.

In this courgette flower a series of deep folds are responsible for bending adjacent thin flat areas to create an overall effect of pleating. This is a principle that can also work in textiles since pleating can be achieved even when only alternate stripes are actually structural folds, provided that the adjacent flat cloth is soft and flexible. An example using a combination of Han damask and plain weave will be shown in Chapter 5.

Later in this book I have chosen four fabric qualities as starting points for design: ribbed/pleated textures, translucency, textiles that are different on the two sides and those that escape the grid of the woven structure. Many other qualities could equally well have been selected, and even the four that have been chosen are obviously not mutually exclusive. Ribbed or pleated fabrics lend themselves particularly well to creating double-sided effects and translucent gauze fabrics may also spontaneously develop wavy effects or pleats, and so on. A few examples of natural objects that might offer both structural and visual ideas for the fabric qualities to be discussed later in the book will give a sense of these multiple possibilities.

For ridged and pleated textures the origami-like structures of leaves and insect wings have already been mentioned, but many other strongly textured forms can provide ideas. Flowers often have quite thin, delicate petals and these may be given adequate stiffness through regularly spaced ribs or folds. Seed pods are often also deeply ridged to provide stiffness with great economy of material, an arrangement that can also work well in textiles.

The sculptural seed pods of Nicandra physalodes show a beautiful combination of strong curved ridges interspersed with thinner concave surfaces, creating striking three-dimensional forms.

Both outer and inner surfaces of this bivalve shell have attractive qualities, with rippled ridges on the outside and subtle colour gradations and delicately toothed pink edging on the inside. The outer surface rewards close inspection, revealing tiny cross-ribs running across the main ridges. This efficient way of achieving strength with a minimal use of materials echoes the structure of the water lily leaf.

The diversity of structure in shells is a great resource and lovely examples of ridged textures are shown in Hans Meinhardt’s remarkable book The Algorithmic Beauty of Sea Shells, which also offers plenty of inspiration for pattern and colour. Not only do many objects such as leaves and shells have interesting textures but frequently they are also different on the two sides, so can offer ideas for fabrics that are both highly textured and double sided. As well as living things, other aspects of the natural world such as stones, rocks and various geological formations can be a wonderful source of ideas. Stacey Harvey-Brown draws on the forms of sand ripples, volcanoes and mountains in her highly textured fabrics.

Examples of transparency and translucency abound in the natural world and can be very instructive, both visually and in terms of cloth quality since the substance of translucent surfaces can vary greatly, ranging from the crisp quality of honesty seed heads to the soft creped texture of poppies. Beautiful lacelike effects can be seen in leaf skeletons, and the different weights of the supporting ribs, from main stems down to the smallest vessels, provide appropriate strength where necessary while also making the visual effect of the surface more varied and interesting. The way that local dense areas serve only to emphasize the transparency of the whole is a lesson that can usefully be applied to textiles.

Leaves have large variations in scale from major to minor ribbing and this is particularly well revealed in leaf skeletons.

Physalis seed pods produce exceptionally beautiful skeletons and these can be particularly interesting when only partly skeletonized.

This detail of a guinea fowl feather shows the delicate structure of the barbs and barbules and the attractive variation in pigmentation.

Feathers also provide beautiful examples of translucency, with their delicately interlocking barbules, particularly where there are contrasts of pigmentation. Another interesting aspect of transparency in nature is that often another surface can be seen behind the transparent one, so the experience is one of looking through rather than simply at the surface, something that can be exploited in textiles by using double or multiple layer cloths.

Some of the natural objects that have already been mentioned in relation to textured or transparent textiles can also suggest ideas for double-sided fabrics, but there are many other possible sources of ideas. As well as the many beautiful leaves that have strikingly different sides, other plant structures such as pieces of bark can show attractive contrasts between the inner and outer surfaces. And when it comes to textiles that aim to escape the formal grid of warp and weft, the list of examples that could provide inspiration must be endless – what in nature is perfectly straight and rectangular? Perhaps this is precisely why weavers so often want to break out of their grid.

OTHER LESSONS FROM NATURE: FIBONACCI TO FRACTALS

Philip Ball’s book Patterns in Nature includes many dramatic images, while his trilogy Shapes, Flow and Branches provides more detailed scientific explanations of the forces involved. He deals extensively with the mathematics behind natural patterns, ranging from the Fibonacci series, which can be seen in many plants, to fractal forms that show self-similarity over many scales. Such natural patterns can be a source of ideas for designers in many fields.

Philip Ball opens Shape, the first of his trilogy, with a discussion about whether it should be possible to use shape, pattern and form as a signature of life: ‘That doesn’t seem an unreasonable thing to do, does it? Surely, after all, we can distinguish a crystal from a living creature, an insect from a rock?’ He goes on to explain that on many occasions making this apparently obvious distinction is not at all easy. He quotes extensively from D’Arcy Thompson, a biologist whose book On Growth and Form strongly emphasizes the underlying forces behind the development of form, giving numerous examples where inorganic and organic forms closely resemble one another because similar forces have been involved in their creation. Just as the ripples on the shore, the outline of the hills or the shape of clouds are subject to physical forces so also are all living things: ‘Cell and tissue, shell and bone, leaf and flower, are so many portions of matter, and it is obedience to the laws of physics that their particles have been moved, moulded and conformed.’

Thompson goes on to suggest that objects themselves reveal the forces involved in their formation, so any object, organic or inorganic, can be thought of as a ‘diagram of forces.’ Designers and makers in all fields are being offered a useful hint here because thinking about how natural forms have developed, what forces have shaped them, can sometimes allow us to exploit underlying principles of growth and form in our designs as well as being inspired by the beauty of nature.

WEAVING AS INSPIRATION AND METAPHOR

The beginning of this chapter described how the relationship between design and the study of nature is a two-way street. As designers and makers we must gratefully acknowledge our debt to nature itself and also to the scientific ideas that help us make sense of it, but we may also take some satisfaction from the way that scientists in their turn have drawn upon the human activities of designing and making as sources of both practical ideas and vivid metaphors. Weaving seems to bear this out, perhaps more than any other branch of design. The close interplay of different elements in weaving is so well known to everyone and so perfectly captures something important about the interconnectedness of the natural world that it appears irresistible as an image. When D’Arcy Thompson discusses the relation between evolution by natural selection and the mechanical constraints of physics that govern all living things, he concludes that these ideas are woven together ‘like warp and woof’. And when the physicist Richard Feynman suggests that understanding things in detail can lead to a broader understanding of the universe, it is weaving that provides him with the perfect metaphor: ‘Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry.’

PART 2

Resources for Design

The material itself is full of suggestions for its use if we approach it unaggressively, receptively.

Anni Albers, On Designing

The interplay of material and structure creates a striking effect in this scarf by Gilian Little. Two sets of wool yarn of different weights and with very different felting properties are arranged so that each weaves only with itself. The easily fulled yarn floats above and below the fine high-twist yarns that form the main part of the scarf. The structure is similar in principle to a deflected double weave but the high-twist wool is itself woven as a double layer. During wet finishing the floating yarns felt together while the high-twist wool shrinks and crinkles but resists felting. (Ann Sutton Collection)

The range of fibres that can be used for textiles is too wide for an attempt at a complete overview here, but some commonly used fibres with very different qualities will be described. The interplay of these materials with weave structure is complex and provides a useful starting point for design but when working with traditional weaves, it is often worthwhile to ‘play around’ with them in an experimental way as well as using them in their ‘classic’ forms. With different materials or on different scales some of them may become interestingly unrecognizable! An awareness of the characteristics of various materials and structures and how they interplay will give a sense of their potential for design, so these ‘resource’ chapters will take a selection of traditional weaves and show how versatile they can be depending on material, scale and sett. Many techniques stretch back over hundreds of years, even millennia, so in these cases there will also be some account of their history.

CHAPTER 2

Material Resources: Fibres and Yarns

Structures are made of materials… but in fact there is no clear-cut dividing line between a material and a structure. Steel is undoubtedly a material and the Forth bridge is undoubtedly a structure, but reinforced concrete and wood and human flesh – all of which have a rather complicated constitution – may be considered as either materials or structures.

J. E. Gordon, Structures

WHAT IS A MATERIAL AND WHAT IS A STRUCTURE?

It is quite common to talk about materials and structures as though they were distinct categories but, as Professor J. E. Gordon explains, the dividing line is not always sharp. When talking of materials, most weavers tend to conflate the properties of the fibre and the yarn – for example, the inherent strength and stiffness of linen fibres are properties that are also evident in the yarns constructed from these fibres. In a general way this works fairly well but it is still worth taking time to consider the basic properties of fibres and the ways these may be impacted by different preparation and spinning methods and also finally modified by any finishing processes applied to the woven cloth. There will be no attempt here to be comprehensive because the range of fibres that are usable for textiles is vast. A brief survey of some commonly used fibres that vary greatly in their physical properties will give a sense of the range of possibilities.

MATERIALS AND THEIR PROPERTIES

It helps to start by considering some general properties of materials so that the specific behaviours of textile fibres can be seen in a broader context. Professor Gordon has a lively and amusing way of capturing the fundamentals about materials and structures and he particularly emphasizes strength and flexibility:

A biscuit is stiff and weak, steel is stiff and strong, nylon is flexible and strong, raspberry jelly is flexible and weak. The two properties together describe a solid about as well as you can reasonably expect two figures to do.

But he then goes on to discuss a third important property, that of toughness, the ability of a material to absorb energy without breaking. This is particularly relevant to weavers as our materials are greatly in need of this energy-absorbing capacity as we stretch them under high tension and abrade them with the heddles and reed. So, if we include toughness, the four main natural textile fibres can be characterized in this way:

• Flax is strong and stiff but has poor toughness.

• Wool is weak and flexible but moderately tough.

• Cotton is moderately strong and flexible but not very tough.

• Silk is also moderately strong and flexible but it is extremely tough.