Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

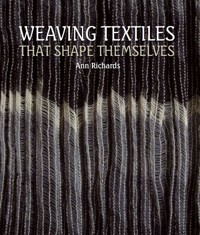

Weaving Textiles That Shape Themselves sounds like a contradiction in terms, but this book sets out to show how textiles can do precisely that: shape themselves. Weaving with high-twist yarns and contrasting materials can create fabrics with lively textures and elastic properties. Although these fabrics are flat on the loom, they are transformed by washing - water releases the energy of the different yarns and the fabrics 'organize themselves' into crinkled or pleated textures.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 316

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Dragonfly Pleat’ scarf. Linen and silk.

First published in 2012 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This impression 2020

This e-book first published in 2024

© Ann Richards 2012

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4360 0

Cover illustration: ‘Gauze Pleat’ scarf. Tussah silk and mohair.

Dedication

To my mother.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Woven Textiles as Self-Organizing Structures

1 FIBRES, YARNS AND WEAVE STRUCTURES

2 TWIST AND TEXTURE IN WEAVE DESIGN

3 MAKING SENSE OF YARNS

4 SIMPLE COMPLEXITY

5 SUBTLE INTERPLAY: FORCEFUL FLOATS

6 SUBTLE INTERPLAY: DOUBLING UP

7 TEXTILES THAT SHAPE THEMSELVES

8 PRACTICAL TECHNIQUES FOR HIGH-TWIST YARNS

9 TEXTILE CONNECTIONS

10 DESIGNING AS A CONVERSATION

Bibliography

Useful Contacts

Suppliers

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank all the teachers, friends and colleagues who developed my interest in this field – especially Mary Restieaux, who encouraged me to apply to study at West Surrey College of Art and Design (Farnham), Margaret Bide, who accepted me as a student (and has worked tirelessly to ensure that high-twist woollen yarns remain available for handweavers), and Amelia Uden and Deryn O’Connor, who were my stimulating and supportive tutors at college. I am conscious also of the influence of the late Ella McLeod, though I met her only briefly, since she founded the weaving department at Farnham and was responsible for establishing its unique ethos. I am also grateful to the late Marianne Straub, who came as a visiting tutor and gave me a great deal of encouragement.

Junichi Arai has, of course, been an important influence and inspiration, and I am very glad that he has allowed me to include some of his work in my book. Reiko Sudo, the other founder of Nuno, also kindly agreed to my including her work and other Nuno fabrics. Ann Sutton, who first introduced me to the work of Junichi Arai and Nuno, has been an ongoing source of encouragement and, as well as allowing me to include a piece of her own work, generously allowed me to borrow textiles from her collection for photography. Inge Cordsen and Kate Crosfield, of Livingstone Studio, have been a great source of help and advice, as well as selling my work over many years.

I would also like to thank all the other designers and artists who have allowed me to include examples of their work in this book: Sharon Alderman, Dörte Behn, Anna Champeney, Fiona Crestani, Lotte Dalgaard, Alison Ellen, Berthe Forchhammer, Mary Frame, Stacey Harvey-Brown, Teresa Kennard, Bobbie Kociejowski, Gilian Little, Noriko Matsumoto, Wendy Morris, Andreas Möller, Jennie Parry, Geraldine St Aubyn Hubbard, Ann Schmidt-Christensen, Lucia Schwalenberg, Emma Sewell, Liz Williamson and Deirdre Wood. All textiles not otherwise attributed are by me.

There are two good friends whom, sadly, I am unable to thank personally as they are no longer alive, but I am very glad that family members were happy for me to use examples of their work here. I am grateful to Brian Austin for permission to include a piece by Gusti Austin Lina, and to Peter Reimann for allowing me to include work by Sheila Reimann.

Photographs have been taken by the designers and artists themselves and also by Ole Akhøj, Joe Coca, Alan Costall, Ian Hobbs, Jürgen Liefmann, Joe Low, Colin Mills, Heiko Preller and Carol Sawyer. Other photographs are by the author.

I would especially like to thank Alan Costall for help and advice while I was writing this book.

INTRODUCTION:Woven Textiles as Self-Organizing Structures

The structure of a fabric or its weave – that is, the fastening of its elements of threads to each other – is as much a determining factor in its function as is the choice of the raw material. In fact, the interrelation of the two, the subtle play between them in supporting, impeding, or modifying each other’s characteristics, is the essence of weaving.

Anni Albers, 1965

In some ways, the title of this book is, of course, meant to be playful and a little provocative. Designing and weaving textiles is hard work. Why do I want to say they can ‘shape themselves’?

It makes sense to talk about ‘self-organization’ in designed structures because good design is not merely the imposition of form, but depends also on what materials and structures can do. Although the designer can start with a specific aim in view and choose what elements to put together, the materials and the structure will determine what happens, sometimes in surprising ways. Through complex interactions, these elements may organize themselves into something rather different from the intended design. This can perhaps give a disappointing result but it may also, sometimes, produce something more subtle and interesting than the designer’s first thought. Even an apparent failure can form the germ of a new idea. So it is necessary to be constantly attentive to this ‘subtle play’ of material and structure and be ready to respond, making best use of their characteristics. The design process must be a series of experiments, with the designer reflecting carefully upon each result and trying to understand what is happening before deciding on the next step.

‘Doublecloth Loop’ scarf, in spun silk and crepe wool, designed to be interlaced around the neck in a variety of different ways. The crepe wool weft gives a textured surface to the scarf, and changes in weave structure create flared borders.

Complex interactions of this sort are characteristic of all designing that is pursued through the process of making, no matter what the material, wood, clay or metal. But woven textiles show this ‘self-organizing’ tendency to a striking degree, especially if very strong contrasts of material and structure are used. Powerful textures can emerge during wet finishing, from the interplay of fibre, yarn twist and weave structure. Such fabrics undergo a surprising transformation from the smooth, flat state that they have on the loom, to the textured surfaces they develop when they have been soaked in water. As water is absorbed, yarns of differing elasticity pull against one another and ripple or buckle the fabric.

The most dramatic effects are produced by yarns that are very highly twisted and these form the main focus of this book. High-twist yarns can create striking, three-dimensional effects, because the stress imposed by the spinning process gives these yarns considerable energy, which is released by the addition of water. Spontaneous shrinking and spiralling movements of the yarns then cause the fabric to crinkle or pleat, creating highly textured, elastic fabrics. It is also possible to vary the yarn twist or weave structure in different areas of the fabric, resulting in differing amounts of contraction, so that rectangular pieces of fabric assume flared, curved or irregular lozenge shapes when they are wet finished. These textiles can truly shape themselves.

The book begins with an introduction to the physical properties of different textile fibres, the structure of yarns and the influence of yarn twist on the properties of yarns and fabrics, since these factors form the basis of design in woven textiles. Chapter 2 aims to give some historical context, since some techniques go back thousands of years. Chapter 3 deals with yarn counts and how these can be used for calculations of yarn diameter, cloth setting and twist angle, which provide a sound basis for weave design in general, but are particularly useful when working with high-twist yarns.

The next four chapters cover the use of various weave structures that work well with high-twist yarns and contrasting materials. This section is not intended to give an exhaustive treatment of different weave structures, since many excellent books on this topic are already available. Rather the aim is to draw attention to fundamental characteristics and properties of different groups of structures, showing their potential for creating textured fabrics.

Chapter 8 deals with practical techniques for handling high-twist and difficult yarns. This is followed by a short chapter, which briefly touches on some topics related to the main theme: the use of synthetic shrinking yarns, other methods of creating textured effects and shaping, and the use of high-twist and shrinking yarns with textile techniques other than weaving.

The concluding chapter discusses sampling, building on experience and the idea of design as ‘reflective practice’. When working with powerful yarn twists, the unpredictability of the interactions means that apparently modest changes to any of the elements can create major repercussions within the fabric. So although there are many examples throughout the book (some with details of yarns and cloth settings), there are no projects in the form of detailed ‘recipes’ that are intended to be followed exactly, since any departure from precise specifications could considerably change the result. The availability of particular yarns is always variable, so it is much better to understand general principles on which personal experience can be built. However, the final chapter includes some suggestions for sampling that I hope will be helpful as a starting point for anyone who has not worked with these yarns before.

Although high-twist yarns and strongly textured textiles form the main focus of the book, I hope that much of the information on both technique and design may be useful to weavers generally. I have included illustrations of textiles by many designers and artists, and have referred in the text and bibliography to other weavers who are doing impressive work in this field. So I hope this book will also serve as a celebration of the variety and beauty of the textiles being produced in this most exuberant area of weave design.

Wool and silk crepe yarns are played off against stiff metal yarns, to create close-fitting bracelets with rippled edges.

CHAPTER 1

FIBRES, YARNS AND WEAVE STRUCTURES

A deep, intuitive appreciation of the inherent cussedness of materials and structures is one of the most valuable accomplishments an engineer can have. No purely intellectual quality is really a substitute for this.

Gordon, Structures, 1978

Replace the word ‘engineer’ with ‘designer’ in this quotation from Gordon’s excellent book Structures, and you have a good description of a successful designer/maker. There is no substitute for working with materials and processes to develop a deep, intuitive sense that goes beyond theoretical knowledge. Technical specifications of the properties of materials and structures are inevitably measured on the basis of ‘other things being equal’. In the real situation of designing, of course, other things never are equal – everything is going on at once! This complexity can sometimes seem unmanageable. And it is here that an intuitive sense of the ‘cussedness of materials and structures’ really pays off.

A fabric that spontaneously pleats itself is shown in the loomstate (top) and after wet finishing. I was a beginner in weaving when I first became aware of this effect, while trying to make a fabric with a smooth, flat surface. At the time, I was not too pleased. Later, I came to appreciate the way the cussedness of materials and structures can sometimes be a gift to the designer!

All the same, it is well worth knowing something about the scientific measurements of the properties of different materials and structures. This forms a useful base on which to build the ‘tacit knowledge’ that can only be acquired through practical work. This chapter deals with some basic characteristics of fibres, yarns and weave structures and the way these affect the finished fabric. Although this involves going into apparently dry technical details, it is worth understanding these basic principles, because so much of the work of making textured textiles relies on subtle differences of material and structure. Also, in the process of examining these various properties separately, the difficulties of designing become apparent. Time and again, it is the interplay of properties that is important.

The Properties of Textile Fibres

Although a very wide range of materials can be used to make textiles, the vast majority of all textiles made from natural materials are in cotton, flax, silk or wool. So I want to look at some properties of these common materials that are particularly relevant to their use in textiles.

Strength

One of the most important properties is strength. Scientifically, this is measured by seeing how much weight a sample of the material can support before it breaks, and such tests show that flax is a very strong fibre, while silk and cotton are of moderate strength and wool is very much weaker. Weavers tend to check the strength of yarns by pulling on them to see how easily they break, which is clearly a rough and ready equivalent of the scientific test, and gives similar results. (This is not, of course, strictly comparable with the scientific test, which is done on a sample of the fibre itself. As weavers, we are doing our test on a structure – the yarn. The structure imposed by the spinning process also influences the strength of the yarn.)

Toughness

But, of course, some of the problems that arise in weaving are not really about strength as such. For example, although linen yarns are strong in the sense that they seem hard to break deliberately, they actually break more easily during weaving than silk, cotton and wool yarns, which are not as ‘strong’. The issue here is toughness, the ability of a material to absorb energy without breaking. Silk is much the toughest of the natural fibres, with wool and cotton much less so, while flax is relatively brittle. A small amount of damage to a flax fibre easily starts a crack that runs rapidly right through the fibre and causes it to break. This ties in with the experience that linen yarns are easily damaged by the heddles and reed. A simple test for abrasion resistance is to hold a short length of yarn under tension and run a fingernail back and forth along it. It can be surprising to see how an apparently ‘strong’ linen yarn will sometimes break easily under this treatment. Also a shuttle hitting a linen end stuck in the middle of the shed will often snap the yarn, when a silk yarn would simply absorb the blow. In this case, it is not really the suddenness of the force that is the main problem, but the amount of energy the shuttle has as it flies through the shed. It not only starts cracks but also has the energy to propagate them rapidly through the material.

Stiffness

There are also often tension problems with linen yarns because flax is a very stiff fibre, compared with silk, cotton and wool. These differences can easily be sensed when handling yarns in these different materials. The flexibility of the wool can readily be felt and seen, as it is easily extensible, and it also shows good elastic recovery, springing back to its original length. Cotton and silk seem moderately flexible, and flax is very inflexible. Many of the weaving difficulties associated with linen yarns are due to the extreme stiffness of the flax fibre. Any slight differences in the tension of individual warp ends makes weaving difficult, compared with a wool yarn that would easily absorb these variations. Also, flax only shows elastic recovery over a small range of stresses. Beyond this point it will not spring back to its former length, so any individual threads in a warp that are accidentally stretched will become slack and interfere with weaving.

Fibre Properties in Textured Textiles

It is clear that strength and toughness are the most important properties of textile fibres, in terms of their general suitability for weaving, especially as warp yarns that must withstand both tension and abrasion. However, from the point of view of designing strongly textured textiles, the stiffness of fibres is particularly interesting. At first sight, the fact that linen is so stiff seems to mark it out as difficult to work with, and it is certainly often described as ‘unforgiving’. But, quite apart from the fact that linen is a very beautiful material and well worth the extra effort needed in handling it, it is very useful when designing textured textiles. The extreme contrast between the stiffness of linen and the flexibility of the other natural fibres gives plenty of scope for playing these different qualities off against one another to create textured effects.

Variations in fibre stiffness also mean that the properties of high-twist yarns vary, depending on the material. Twisting fibres into yarns imposes a stress on them, and this is the cause of the texture produced by high-twist yarns. Stiff materials that resist twisting react strongly to stress and so can make particularly effective high-twist yarns. The mechanism of this stress reaction will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. Stiffness is determined not only by the intrinsic differences, for example between such fibres as cotton, silk and wool, but also the thickness of the fibres. The stiffness of a fibre increases more rapidly than its diameter, and consequently wool, with its wide range of fibre diameters found in different breeds of sheep, is a particularly interesting material for high-twist yarns. Different reactions are given by woollen yarns constructed from fine fibres, and worsted yarns made from thicker longwools. The impact of these differences will be explored in Chapter 4.

Structure of Yarns

When, as weavers, we carry out informal tests of the physical properties of our materials by breaking yarns and so on, we are confounding the properties of the fibres themselves and that of the structures made from them – the yarns. The structure of yarns varies and can considerably modify the properties of the fibres.

This fabric uses the effect of soft pleating shown at the beginning of this chapter, but now the pleats also have a rippled effect, because of the contrast between stiff linen yarns and more flexible silk ones.

Yarns can be twisted in two different directions (Z and S) and they can also be twisted by different amounts to give varying angles of twist.

Yarns may either be formed of continuous filaments or spun from shorter fibres. Continuous filaments, such as silk, do not require twist to give them strength, though they are usually lightly twisted to make a yarn that is more coherent. Yarns made from short fibres, such as wool, cotton or linen, must be twisted in order to form a yarn of sufficient strength for weaving. Yarns may be twisted either to the left or the right and these different directions are indicated by the letters S and Z, the diagonal strokes of these two letters lying in line with the fibres in the yarn. A yarn may also be twisted by different amounts and, as more twist is added, the fibres within the yarn will be seen to form a progressively larger angle with the axis of the yarn.

This twist angle is an important fundamental property of the yarn, which is covered in more detail in chapter 3. In general, the strength of spun yarns increases with the amount of twist, and this effect is familiar to anyone who spins their own yarn. At very low twists the fibres are free to slip past one another, causing the yarn to break. As twist is increased, the fibre slippage is reduced and the yarn becomes stronger. However, strength increases only up to a certain limit. Beyond this point, further twist imposes a progressively increasing stress, which weakens the yarn. Consequently, there will be an optimum amount of twist to give maximum strength for any particular fibre, depending on such characteristics as length, fineness, smoothness and stiffness. Yarns spun to this optimum twist will generally be rather hard, so for many purposes yarns are spun to a twist angle below the optimum for strength.

An unbalanced yarn will twist back on itself to make a plied yarn.

Stress and the Creping Reaction

The stress produced by high levels of twist has an additional effect. Yarns become unbalanced, tending to crinkle and spiral in an attempt to escape the stress imposed on them, and it is these movements that create textured ‘crepe’ effects within a woven fabric. Although some fibres produce yarns that react in this way at fairly modest levels of twist, most yarns will need to be spun to higher than the optimum twist required for strength, if they are to have good creping properties (commercial crepe yarns will be well above this optimum). High-twist yarns are therefore usually weaker than normal yarns.

If allowed to, an unbalanced yarn will readily fold back upon itself, forming a double strand twisted in the opposite direction to its initial twist. As this occurs, the single strands are untwisting, allowing the fibres to lie at a lower angle with the axis of the yarn, thus reducing stress and producing a balanced yarn, which shows no tendency to crinkle or spiral. This reaction is the basis for the process of combining two or more strands of a singles yarn to create a plied (or folded) yarn. The letters S and Z are used to indicate plying direction in a similar way as for singles yarns.

Direction of Twist

Unlike the amount of twist, the different directions of twist do not influence the physical properties of the yarn, such as strength, but Z and S yarns do reflect light in different directions and so can produce subtle ‘shadow’ stripes and checks when the yarns are woven (seeChapter 2). Also, as the warp and weft interlace, different fabric characteristics develop, in terms of handle and surface texture, depending on whether these yarns are both of the same twist (Z × Z or S × S) or have different twists (Z × S). Textural differences are particularly strong with high-twist yarns, and this will be covered in detail in Chapter 4.

Fibre Alignment

A further variation in yarn structure is the extent to which fibres are aligned along the length of a yarn. This greatly affects its properties, so that different preparation and spinning methods can result in very different yarns, even when using the same fibre. But since the fibres themselves also vary in their inherent properties, the interplay between fibre and yarn structure produces a wide variety of yarn qualities. Yarns that are strongly aligned have a smoother surface than those that are less strongly aligned, and they are also more compact, and consequently stiffer. These differences offer many possibilities for design, especially when working with high-twist yarns (seeChapter 4).

Weave Structures

Although weave structures can be thought of as having certain intrinsic properties, it is important to remember that these are modified by the materials that are used. As Anni Albers makes clear, it is the interplay of structure with material that is the essence of weaving. Peter Collingwood nicely captures the way that sometimes the characteristics of the structure will be dominant and sometimes those of the material:

Although structure is all-important, the physical characteristic of an object is naturally also influenced by the material used in its making. The resulting interaction between material and structure is an absorbing study; for sometimes the material is dominant – compare a silk sari with a wooden fencing panel, both interlaced in plain weave – and sometimes the structure is dominant – compare a felted piano hammer with a knitted Shetland shawl, both made of wool fibre.

Collingwood, 1987

The sett (the spacing of the warp ends and weft picks) also interacts with the weave structure in determining the characteristics of the fabric. For example, plain weave has the maximum number of intersections and so, in principle, can form the firmest structure. In contrast, in twill weaves the yarn passes over and under more than one warp or weft thread, forming a float. This structure allows yarns to move more freely, creating more flexible fabrics, with a greater potential for shear in the bias direction and good draping qualities. However, this applies only if all other things are equal. So, for example, a very openly spaced plain weave fabric could break the ‘rule’ given above and be more flexible than a twill fabric that has been set very closely.

Scarf in linen and silk, with a textured effect in plain weave.

These principles are particularly important when working with high-twist yarns, as it is necessary to allow adequate space for the free movement of these yarns, which will create texture within the fabric. However, this may be achieved either by an open sett or through the structure of the weave (or both). Because a very open plain weave can allow considerable yarn movement, a wide variety of textured effects can be produced in this simple structure, using high-twist yarns and contrasts of material. So it is not essential to be familiar with complex weave structures to design successfully in this way. Chapter 4 is devoted to techniques for working with simple weaves.

However, additional possibilities come into play if the designer is able to exploit weave structures using long floats. Twills are commonly constructed with relatively short floats, with the yarn passing over only a few threads (though longer floats can in principle be used), but many other weave structures are intrinsically characterized by very long floats, so that yarns emerge from the fabric for some distance. These floats allow high-twist yarns complete freedom to spiral, crinkle and contract, and such structures can therefore be used to produce strongly three-dimensional effects (seeChapter 5). More complex weaves, involving two or more layers of cloth, can also be used to create textured effects using high-twist yarns (seeChapter 6).

‘Square Waves’, a double cloth in silk and wool that exploits long floats to create a texture.

Influence of Yarn Twist on Fabric Properties

Yarn twist has an important influence on the appearance, handle and functional properties of all fabrics, so twist is always an important element in textile design. But although the issues covered in this section are relevant to textiles generally, particular emphasis is put on their importance for designs that exploit high-twist yarns.

Uniformity and Openness of Weave

As twist is increased, any yarn unevenness becomes more obvious, as twist accumulates in the thinner areas. Also, as fibres are pressed more closely together, there is a decrease in the diameter of the yarn. This is usually ignored in formulae for calculating yarn diameter – softer spun yarns can be more easily packed together so that an estimate of maximum sett is useful for both hard and soft spun yarns of the same count (seeChapter 3 for more about yarn counts, yarn diameter and cloth setting). However, fabrics made with moderately hard-spun yarns do appear more open (voile fabrics exploit this fact) and any unevenness in the yarn is particularly visible in such an open weave. When very highly twisted yarns are used with open setts, the effect is different, because any yarn unevenness becomes less noticeable as yarn movements and the texture of the fabric come to dominate the appearance of the cloth.

Lustre

Lustre is highest when the fibres of a yarn are parallel to the axis of the yarn, so as twist is increased in a singles yarn, lustre will progressively decline. Although silk is the most lustrous of the natural fibres, once the natural gum (sericin) has been removed, crepe silks are singles yarns that are very highly twisted, so they are not lustrous. They often also retain the gum, which further dulls their surface. For plied yarns, the amount of lustre is dependent on the relation between the amounts of twist inserted during the spinning of the singles and that given to the final plied yarn. For the fibres to be parallel to the axis of the yarn, the ratio of the plying twist to the initial spinning twist needs to be 0.7 (assuming that the singles yarns are of the same thickness and that the plying twist is in the opposite direction to the singles twist) and this results in a balanced yarn. Plying is occasionally used for crepe yarns, for example in linen, which is a fairly lustrous fibre, but the plying twist is in the same direction as the twist in the singles, to create an unbalanced yarn, so this yarn has a dull surface. Clearly, lustre and a high level of twist cannot be combined within a yarn, but lustre can be very effectively used in strongly textured designs, through a suitable combination of high- and low-twist yarns.

Wrinkle Recovery

In general, fabrics woven with yarns of moderate twists give the best balance between wrinkle recovery and maintaining their press after ironing. With very softly twisted yarns, fabrics are so limp that they easily shed creases and also readily lose their press. With hard-spun yarns, fabrics hold their press but also easily retain creases. This is because loosely spun yarns allow fibres to move and escape from pressure, or straighten out when it is removed, while hard-spun yarns restrict fibre movement. However, these principles apply to ‘normal’, fairly closely set cloths made with yarns that are firmly spun but not highly unbalanced. With very high-twist yarns and open setts, yarn movements come into play and these can produce springy, textured fabrics that resist crushing and creasing.

Shrinkage

Normal shrinkage (as opposed to felting shrinkage) is due to the swelling of textile fibres on wetting, which causes the diameter of the yarn to increase and the fibres to come under stress. The yarn will shrink to relieve this stress, and this effect is most marked with fairly highly twisted yarns, where the fibres are already tightly stretched. Consequently, the amount of shrinkage increases with increased yarn twist. As well as causing shrinkage in many ‘normal’ fabrics, this swelling reaction is the basis of the textured effects produced in crepe fabrics, because for very high-twist yarns, shrinkage alone is insufficient to relieve the stress and so yarn movements also come into play.

Felting

The felting of wool depends on individual wool fibres responding to heat and agitation by shifting and becoming entangled with one another. This is only possible if the fibres have enough space to move. So, as yarn twist is increased and the yarn becomes more compact, felting is reduced. Direction of twist also has an influence, since when it is the same in warp and weft, a phenomenon called nesting comes into play, which restricts the movement of yarn and so reduces felting.

Nesting

When warp and weft are of the same twist, the yarns tend to nest or bed into one another and so produce a firmer but thinner fabric than when opposite twists are used. When a Z pick lies over a Z end the fibres on the underside of the weft pick are in line with those on the upper side of the warp end and this allows the yarns to bed into one another. In contrast, when an S pick lies over a Z end, the fibres lie at 90 degrees to one another – nesting is prevented and the yarns are able to move more freely within the fabric. With yarns of moderate twist, this freedom of movement gives a fuller handle to the fabric.

Nesting. The direction of fibre twist is shown as a solid line for the surface of the yarn and as a dotted line for the underside. When the yarns have the same direction of twist (as on the left), the fibres on the underside of the weft yarn will nest with those on the top surface of the warp yarn. When the yarns are of opposite twists, nesting will be prevented.

It might seem implausible that nesting could occur, given that most normal yarns have twist angles between 15 and 30 degrees, and so the fibres could not be expected to line up as shown in the diagram. However, at the point of contact, the fibre angles increase due to the flattening and curling of yarns that naturally takes place in a woven structure.

In the case of very high-twist yarns, it is unclear how much nesting takes place. Since the twist angle may be as high as 40 degrees, the conditions for nesting appear close to perfect – but on the other hand, the extreme compactness of such yarns could impair nesting. In practice, a comparison of ‘same-twist’ and ‘opposite-twist’ fabrics shows very different patterns of texture (see below and Chapter 4). This suggests that nesting is indeed occurring in the case of same-twist interactions. However, yarn movements are also taking place and these are also contributing to the different textures that develop.

Yarn Movements and Fabric Texture

Several references have already been made to yarn movements as a response to stress. These movements are the mechanism through which high-twist yarns create fabric texture, so it is helpful to understand exactly how they occur. The basic principles are explained here, but more information is given later (in Chapter 4) about how to exploit these effects in design.

Unbalanced Yarns

The concept of unbalanced yarns has already been briefly introduced, but it is necessary to look at this idea in some detail to make sense of the way that yarn twist influences the texture of fabrics. A singles yarn, especially if it is very highly twisted, is under stress. If a length of such an unbalanced yarn is taken and the two ends brought together, the yarn will ply with itself in the opposite direction to its original twist. During this process, twist is being removed from the individual strands and the stress on these fibres reduced, as they come to lie more in line with the axis of the yarn. If a yarn is allowed to ply naturally in this way, a balanced yarn will be produced – that is, one which shows no tendency to untwist or ply with itself. The amount by which a yarn tends to ply back on itself (the snarling twist) gives a measure of the strain energy or ‘liveliness’ of the yarn. Singles yarns are necessarily unbalanced. Plied yarns may be balanced, but they are not always so because during manufacture they are not normally allowed to ply naturally (as described above) but have a plying twist applied to them which may be more or less than that required for perfect balance.

Spiralling of Yarns

An alternative way in which an unbalanced yarn can escape from stress is to untwist. If it is restrained at the ends so that this is impossible, it will instead spontaneously curl, attempting to form a spiral in the same direction as its twist. It is interesting to contrast this reaction with that of plying (which occurs in the opposite direction to the original twist), but a spiral of this type provides another way in which the fibres become more parallel with the length of the yarn, and so relieves the stress on them.

Fabric samples in the loomstate (left) and after wet finishing (right). The different textures of the top and bottom parts of the sample are due to interactions between the warp yarns and wefts of different twist direction. These variations in texture will be discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Yarns try to spiral in this way even after they are woven, and although restrained by the weave structure, these movements can be sufficient to affect the appearance and handle of the cloth. Some movements may become evident as soon as the fabric is cut from the loom and released from tension, but unbalanced yarns only reveal their full energy when the fabric is wetted out. The fibres absorb water and swell, imposing an additional stress on the yarn, which triggers the reaction, and spiralling movements then occur.

These effects are strongly dependent on the amount of yarn twist, becoming more extreme with increasing twist, but they are also influenced by the sett of the fabric. With closely set cloths, the strain energy of the yarn may only be able to escape at the edges of the cloth, causing the corners of the fabric to flip over. With a more open sett, there is enough space for the energy to be released throughout the fabric, causing a disturbance of the whole surface.

Weave structure also has an impact, because with structures that have fewer intersections, there is more scope for yarn movement. The intrinsic characteristics of the different textile fibres also influence the pattern and extent of this texture. The complex interactions of these various factors form the basis for designing with high-twist yarns, and Chapters 4 to 7 go into detail, showing the various textural effects that are possible.

CHAPTER 2

TWIST AND TEXTURE IN WEAVE DESIGN