11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

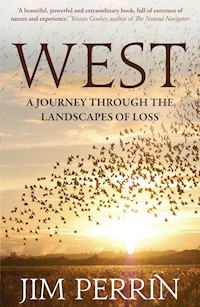

West tells the story of Jim Perrin's life against the lives and deaths of his cherished wife and son, and the landscapes through which they travelled together. It is a complex and sensual love-story, a celebration of the beauty and redemptive power of wild nature and an extraordinary account of one man's journey towards the acceptance of devastating personal loss.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

West

Jim Perrin is one of Britain’s most highly regarded writers on travel, nature and the outdoors, and in his youth was one of the country’s most notable rock climbers. He is a regular contributor to the Daily Telegraph, Guardian, Climber and The Great Outdoors. Among many other awards, he has twice won the Boardman Tasker Prize for mountain literature and was voted Scottish Columnist of the Year 2009. He has written twelve books to date, including Menlove, The Villain: A Life of Don Whillans, River Map, The Climbing Essays and Travels with The Flea. He is a Fellow of the Welsh Academy, an Honorary Fellow of Bangor University, and the Guardian’s Country Diarist for Wales.

‘A brave, painful, beautiful memoir. This is a journey for which there is no conclusion; grief doesn’t resolve, doesn’t get cured. But it is a search for, and perhaps an arrival at, greater understanding… Perrin has been described as a “vivisector”, wielding words as unflinchingly as a scalpel. In West, he turns the scalpel on himself.’ Susan Mansfield, Scotsman

‘A very moving memoir of lives shared and lost… West achieve[s] a kind of grandeur.’ Andrew Motion, Guardian

‘A paradoxically vigorous, lovingly detailed account of bereavement.’ Stephen Knight, TLS

‘Perrin writes the blues, a life-affirming, uplifting journey of being; a love story. Perrin is one of the best landscape writers we have. He hasn’t written this book for anyone to feel sorry for him, he’s written it as an evocation of wild nature in all of us.’ Paul Evans, BBC Country File Magazine

‘Jim Perrin is one of the most distinguished voices on the multiple roles of nature and countryside in British cultural life. West is his finest and most important work to date: a blend of philosophical insight, political challenge and soaring lyricism.’ Mark Cocker, author of Crow Country

‘West takes the shattered heart and carefully, compassionately, mercifully, and with almost angelic generosity, rebuilds it… West is an immensely readable book; erudite, witty, disarming and seductive. And it is ultimately a book about joy.’ Niall Griffiths

‘Jim Perrin’s tragic losses bring into focus all that has been important to him in a life lived, one full of extremes of nature and experience. West is an invigorating and frequently joyous reflection of what it feels like to be alive.’ Tristan Gooley, author of The Natural Navigator

‘In this astonishing book, as much factual novel or epic prose poem as anything else, Jim Perrin takes us on a celebratory, often hilarious, yet profoundly moving, journey through an intricate weave of lives lived, loved and lost. In recalling his wife and son, he conjugates love, pride and pain into an eloquent reflection on grief and mortality, set harmoniously into his lifelong preoccupations with travel, climbing and nature.’ Aonghas MacNeacail

‘This “autobiography” is a book of elemental passion, written with an exact elegance and a remarkable range of reference. It is a book of profound loss, intense joy, and a hard-earned wisdom. It possesses the strange beauty of a real work of art.’ Gwyn Thomas

‘This may be a book about grief but don’t expect misery: West pulses with life’s vitality, is shot through with resilient spirit. Perrin, a writer peerless when mapping landscapes, now turns his attention to inner lands, to the empty plains of loss. He then fills them with memories of two people who were as dear to him as breath, a son and a lover who left chasms in the heart on their departure. What does it tell us? That life goes on, and thrillingly so. And that grief is the deepest lesson, if you’re willing to learn.’ Jon Gower

West

A JOURNEY THROUGH THE LANDSCAPES OF LOSS

Jim Perrin

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2011 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Jim Perrin, 2010

The moral right of Jim Perrin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The author and publisher would gratefully like to acknowledge the following for permission to quote from copyrighted material: The Savage God: A Study of Suicide by Al Alvarez, published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson, an imprint of the Orion Publishing Group, London; The Widower’s House by John Bayley by permission of Gerald Duckworth & Co Ltd; The Uses of Enchantment by Bruno Bettelheim. Copyright © 1975, 1976 by Bruno Bettelheim. Reproduced by kind permission of Thames & Hudson Ltd. The Gamble, Bobok, A Nasty Story by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, tr. Jessie Coulson © 1966, reproduced by permission of Penguin; On Murder Mourning and Melancholia by Sigmund Freud, tr. Shaun Whiteside © reproduced by permission of Penguin; The Uncanny by Sigmund Freud, tr. David McLintock © 2003, reproduced by permission of Penguin; lines quoted from ‘Ripple’ by Robert Hunter © Ice Nine Publishing Company. Used with permission; ‘Rocky Acres’ in Robert Graves, Collected Poems© 1965, reproduced with permission from A. P. Watt on Behalf of the Trustees of the Robert Graves Copyright Trust and Carcanet Press; ‘Darn o Gymru Biwritanaidd y ganrif ddiwethaf ydoedd hi’, a line from ‘Rhydcymerau’ by D. Gwenallt Jones from Eples, reproduced by kind permission of Gwasg Gomer; ‘Funeral Music’ by Geoffrey Hill reproduced by kind permission of the author; ‘Erntezeit’ (‘Harvest-time’) by Friedrich Hölderlin in Leonard Forster (ed.), The Penguin Book of German Verse, 1957, reproduced by permission of Penguin; ‘Distance Piece’, 1964, by B. S. Johnson © reproduced by permission of MBA Literary Agency; lines from ‘On Raglan Road’ by Patrick Kavanagh are reprinted from Collected Poems, edited by Antoinette Quinn (Allen Lane, 2004) by kind permission of the Trustees of the Estate of the late Katherine B. Kavanagh, through the Jonathan Williams Literary Agency; reprinted with the permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from The Drowned and the Saved by Primo Levi. Translated from the Italian by Raymond Rosenthal. Copyright © 1986 by Giulio Einaudi Editore s.p.a. Torino. English translation Copyright © 1988 by Simon & Schuster, Inc.; ‘Braken Hills in Autumn’, in Complete Poems by Hugh MacDiarmid reproduced by permission of Carcanet Press; ‘I saw you among the apples’, in Hymn to a Young Demon by Aonghas MacNeacail reproduced by kind permission of the author; ‘Leaving Barra’ by Louis MacNeice reproduced by permission of David Higham Literary Agency; lines from Detholiad o Gerddi by T. H. Parry-Williams reproduced by kind permission of Gwasg Gomer; Mourning Becomes the Law: Philosophy and Representation © Gillian Rose 1996, reproduced by permission of Cambridge University Press; Autobiography of Bertrand Russell © 1967 Bertrand Russell, published by George Allen and Unwin and reproduced by permission of Routledge and the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation; The Rings of Saturn and The Emigrants by W. G. Sebald, translated by Michael Hulse, published by Harvill Press. Used by permission of The Random House Group Ltd; Lights Out For the Territory © 1997 Iain Sinclair, reproduced by permission of Granta Books; ‘The Rock’, in Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens© The Estate of Wallace Stevens and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd; ‘Yn Yr Hwyr’ by Gwyn Thomas, published by Gwasg Gee, reproduced by kind permission of the author; Blue Sky July© Nia Wyn, 2007, reproduced by permission of Seren Books.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84354 612 2

eBook ISBN 978 0 85789 560 8

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Joe Brown, who is kind, and was always there, and for Jan and Elizabeth Morris, in friendship.

And so it ends.

Some parch for what they were; others are made

Blind to all but one vision, their necessity

To be reconciled. I believe in my

Abandonment, since it is what I have.

Geoffrey Hill, ‘Funeral Music’

Contents

Book One: The Aftermath

1 Furthest West

2 ‘Coming to Rest’

3 Beach of Bones

Book Two: Pre-histories

4 Soldiers in Scapa

5 Reach Out Your hand

6 A Short History of Will

Book Three: Chiaroscuro

7 Quest

8 Communion

9 Idyll

Book Four: Life, dismantled

10 Carity

11 Caravan

12 Catastrophe

Book Five: Hidden Lord of the Crooked Path

13 Searching

14 Solace

15 Landscape of Loss

Acknowledgements

Notes

BOOK ONE

The Aftermath

1

Furthest West

The tide had drained from Omey Strand. I stopped on the road south of Claddaghduff and looked across. Flashes of water still gleamed among the sand. Under a mercury sky their surfaces were scumbled into pewter texture by a cold east wind that funnelled and blustered out of Streamstown Bay. A solitary turnstone picked among clumps of seaweed by the quay, its tortoiseshell colouring merging into the khaki. From over on Omey a flock of knot, late as the spring itself and several hundred strong, took off in swirling flight, flickering dark and then silver against a slate-hued northern sky before scattering down into ebb channels around Skeaghduff, their low, muttering call drifting back just audibly against the wind. The hummocky green island crowded in against the coast. I started the engine of the old black Citroën. It had been Jacquetta’s favourite. She called it our ‘gangster car’ (and in it, daredevil and subversive to the last, she’d collected a speeding ticket that had arrived days after her death. This time I was spared the need for tactics or argument to save her licence). My son Will had borrowed it from time to time, for the style of the thing, to cruise along the quiet roads of Dyffryn Tanat and up to the waterfall, winding the windows down as he pulled away from the house to jet the bursts of gangsta rap at me that completed the pose, the laconic familiar grin on his face, the sideways and backwards toss of the head to acknowledge the joke of it all. The car creaked up on its suspension. I pointed it west down a narrow, pot-holed lane with brilliant green-bladed leaves of a few early flags in the fields to either side, and jounced and groaned across the wave-ribbed sand on to Omey itself. This was where my instinctive flight had led, to Iar Connacht, the westernmost province of Europe and historically one of the poorest and most tragic. There was psycho-geography at work here – the primal instinct Thoreau expressed in his journals and essays:

there is a subtle magnetism in Nature, which, if we unconsciously yield to it, will direct us aright. It is not indifferent to us which way we walk. There is a right way… which is perfectly symbolical of the path which we love to travel in the interior and ideal world… My needle is slow to settle, varies a few degrees… but it always settles between west and south-southwest.1

For me, on impulse I had fled, and fetched up in the furthermost west with a clutch of Irish words to offer some definition and explanation: Iar, which signifies not only ‘west’ but also ‘the end, every extremity, everything last, after, backwards, blank and dusky’; iarsma, ‘after-effects, remainder, remnant’; iartharach, ‘furthermost’; iartestimin, ‘conclusion of a period’; iartaige, ‘unhappy consequence’… As far as I was able at the time to understand from my state of shocked grief, all that seemed to fit and resonate. And it was hazed too with folkloric texture and the salving charge it always carries. A sad child will slip the leash of a brutal contingent and escape into story, and so did I. I knew the myths that led me here to the west: of Goll, a giant and leader of the Fir Bolg, defeated by the Tuatha De Danann but allowed by them to remain in the rough, far exile of Iar Connacht. Goll’s one eye was the westering sun. In the tales he embodies a wisdom that looks askance at triumphalism and can only come from defeat. He represents too the universality of these native tales, the currency of which is loss, grief, mourning, and a background that is elemental, a deemed-sacred continuum of the orders of nature.

There is an enabling quality in this apparently primitive matter, and instinctively I was seeking it out. It allows you to loosen the halter of specific and individual sadness, is a lost and crucial necessity at times of the deepest anguish. I was seeking out the landscapes that correlate. In these first instants of my own journey into loss, for me too the treeless barrens and the wrack-rimmed coasts of Connemara seemed right. Yet I had come here by chance and at unexpected behest.

In the caravan where I was living among the Welsh moors of Hiraethog, two days after Jacquetta’s funeral, my mobile phone had rung. It was an Irish writer – I’ll call her Grainne – whom I’d long known, and been involved with for a time some years ago; tempestuously, disastrously, before Jacquetta and I had come back together:

‘Come across to Galway, Jim – I’ll mind you – you need minding now. There’s the spare room. You’ll be all right here. You can work. We can talk. I’ll not bother you.’

As she rang off, she repeated that formula about minding me. The prospect of being cared for after two years of caring for Jacquetta, often under the most difficult circumstances, had an undeniable appeal, sounded like rest and relief. I considered whether I should go. The westward pull that I had felt with increasing intensity since the evening of Jacquetta’s death-day was near-irresistible now. There is no logic and a continual charge of magic running through your thinking after bereavement, in equal and opposite degree to your being unwitting of the practical and the predictable. To go west was to follow her – the version of thinking my mind had installed under these circumstances on that point was quite clear. To lose her twice in my life was unbearable. She had gone west and I would go that way too. There was nothing to detain me in the caravan by the stream where she and I had mostly lived for the last eighteen months. To continue there was clearly going to become increasingly difficult and inconvenient as well as painful, for pathological savagery circles after a death, breeding in families, seeking a focus and seeking a target, the guilt of those who neglected and exploited and abused fixing invariably post mortem on those who cared for and provided. Autonomous human love is always a threat to those whose claims on affection are based not on right behaviour but through propinquity. In the aftermath of a death, the close and caring bereaved are often made homeless, their joint belongings pillaged, whilst the erstwhile-negligent blood-tied ones are emotionally and materialistically merciless in their reappropriations of the deceased.

My Irish friend’s invitation was in accord with my own desire. I phoned her back, accepted her offer, said she could expect me the following evening. And as I did so, it was with the faint, pained recognition that it was in accord too with Jacquetta’s premonition that after her death this is where I would go:

‘You can talk about poetry and literature with her, and those things excite you and they matter to you.’

‘But I don’t need to talk about them. You and I can be together without the need to talk. We know each other’s thoughts, and are quiet and peaceful, and delight in what’s around us. I wouldn’t change that for anything or anyone. I wouldn’t change you for the world.’

She looked at me in her calm way as I spoke, and when I’d finished she turned to the window of the bedroom in the house into which the last weeks of her illness had forced her to take refuge. We were silent together in the attentive stillness of mutual belonging. Two barn owls were hunting along the stone wall that traversed the moor, the pair of them ghosting pale against brown rushes and grey rocks, close-bound, returning to their roost. Re-attuned, we turned to each other again, and to the sweet ease and right fit of our embrace. Her lips parted and her head tilted back in the habitual way of her arousal. She led me to the bed, the unspoken plane of knowledge between us haunted by the sense of her imminent leaving. I might not have changed her for the world, but the world was one from which she would soon be gone.

*

No more than a bare space of weeks had passed since that moment. Now Jacquetta was smoke and ashes. Will’s ashes too were in their urn in the caravan shrine, waiting on release, myself not yet knowing where or when to bestow them, my grieving for him nine months on hold whilst I’d cared for my woman in her time of dying. And I’d accepted a proposition that Jacquetta had surely foretold:

‘When I’m gone you’ll go to Grainne – she’s more your equal than I am.’

‘You’re my equal in every way, and you are wise and beautiful and desirable to me.’

‘You’ll go to her. I can tell. Make love to me now. I want to feel you inside me…’

*

There are many things, in the first days of grieving, that you do not notice. The neurologist Antonio Damasio writes that ‘con sciousness and emotion are not separable’, and goes on to note that ‘when consciousness is impaired so is emotion.’2 In this frozen state, things pass you by unobserved. You remain for many reasons at best only partially aware. The mind has lost any forward view and your whole focus is minutely backwards. It even blanks out matter that it might be sensible to register with regard to any plans you somehow summon the attention to make. Even the instinct for survival is attenuated, or even unwelcome. Perhaps, in a more alert and circumspect state, I might have thought back to my last meeting with Grainne. I’d picked her up from Manchester airport and driven her back to Wales. At my house, though it was still afternoon, she’d straight away insisted on our fucking. In a frenzy of unzippings and writhings she had me down on top of her on the black sheepskin in front of the hearth. Afterwards, sitting by the fire with my cat Serafina purring on my lap, dizzily post-coital and relaxed, suddenly Grainne launched out of her chair and with a full sweep the back of her hand cracked across my mouth. On the return arc she caught the cat, sent her flying ten feet across the room and sliding under a chair, from beneath which her wide green eyes stared in fearful astonishment as I wiped away the blood that was trickling from my lip and asked Grainne what that was for?

‘You weren’t paying attention to me, only to that fecking cat…’

‘So that merits a smack in the teeth?’

‘What’s the point of having a temper if you can’t use it?’

As with many of Grainne’s sallies, I had no response to that one, nor to the arch, acid sweetness of its west-of-Ireland delivery. The rest of the visit did not go well. I could forgive her the swollen lip and the loose tooth, but not the striking my cat, to whom I was particularly attached. She was large and slender, white with black markings and a lopsided moustache. She’d arrived on my doorstep as a two-year-old stray, had moved in and stayed. My bossy, good-hearted, elderly Welsh neighbour Mair had spotted her across the back-garden fence and – her own cat having recently died – tried to lure her in, but cats and dogs generally bond most closely cross-gender, and she was having none of it. ‘Call her Buddug, then,’ commanded Mair, but I pointed out to her that the Jack Russell at the end of the terrace was a Buddug and we’d not want forever to be inviting her around. Also, I’d already taken to calling the new stray Serafina, after the good witch Serafina Pekkala (a name apparently taken from the Helsinki telephone directory) in the first part of Philip Pullman’s great fantasy trilogy His Dark Materials. For Mair’s sake, I added on the assonant Welsh ‘Seren Haf’ – ‘summer star’ – which appeased her, and I could often hear her whispering the full-version septosyllabics through the slate fence those summer evenings. The next week I went out and found Mair a sleek and biddable tom cat who soon grew round as a football, and down upon whom Serafina, by now fiercely territorial, glowered from high perches with sovereign contempt. She was thin and ill, and had a habit of vomiting in the most inconvenient places – computer keyboards, vegetable baskets, white duvet covers – but a diet of trout fillets, boiled chicken and rice, fillet steak gently fried in butter, and medication from the vet had eventually cured her. One day she’d been sitting in my lap purring like a small rasping bellows, I’d met the languid gaze of eyes the colour of sunlit sea over clean sand seen from a high cliff, and had convinced myself that she was a revenant, was the ghost of my own little Jack Russell, The Flea, on the exact second anniversary of whose death at the age of seventeen she had arrived. The tendency towards magical thinking had long been present in me, the deaths of my loved ones serving only to amplify it.

Grainne and I on this occasion years before had parted on furious terms when, after more nights of angry fucking that had left us exhausted and ill at ease with each other, I’d refused to drive her to her Manchester publisher’s and dropped her at Chester station instead, as heartily glad to be rid of her presence as no doubt she was to be free of mine. It was several years since I’d seen her, though she would email me or ring from time to time to gossip about poets she knew; to talk about her latest book or translations she was working on, or plays she’d seen in Dublin or Paris; to slant in acerbic questions about how ‘the great romance with that girl’ – this despite the fact that Jacquetta was very close to my age and several years older than Grainne – was going; to suggest meetings in Dublin, Paris, Cape Cod, to none of which I agreed. And now, at the most vulnerable I had ever been, I was accepting Grainne’s offer, and hoping it was in good faith. My comic innocence puts me in mind of John Bayley’s in Widower’s House – the last of his trilogy about the death of his wife Iris Murdoch and its aftermath. Had I read that in time, and relished the delicious comic absurdities of it, I might have been forewarned:

Why had Margot come to my bed in the night? Why had Mella become so different so suddenly when she knew that another woman had been in the house? Surely no deep strategy was involved in these actions; they were just a part of human behaviour, its diversions, as one might say, bringing about both troubles and rewards.3

Whatever diversions were to come, I needed to pack, get ready to catch the early ferry from Holyhead, make provision for Serafina’s being fed; and before I left and before the moment left me, I needed to write something, to set down a marker of the time Jacquetta and I had had together, to establish its mythos as a sustaining point of reference for the coming journey into a double grief that the shocks of the last nine months and its terrible gestation had left me too numbed yet to acknowledge. I stayed up that night, shaping the feelings and memories that surfaced in my mind, shading the transition from idyll to tragedy, prefacing the piece with quotations from Simone Weil and Shunryu Suzuki.

The title that came to my mind for the essay thus produced was ‘Coming to Rest’, in recognition of what Jacquetta had brought me. It seems proper to have it at the starting point of this book.

We tell ourselves stories in order to go on living…4

2

‘Coming to Rest’5

To find perfect composure in the midst of change is to find nirvana.

Shunryu Suzuki,Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind

Love is not consolation, it is light.

Simone Weil,Gravity and Grace

It could simply be that I am idle by nature, or that my old legs are giving out. Whatever the reason, these last two years what has given me most pleasure in the outdoors has been coming to rest within a landscape rather than racing through it in pursuit of some distant objective. There has been an additional factor at work here too, a crucial dimension that has brought with it new realizations and ways of seeing. John Berger wrote in one of his essays – important and insightful reading for anyone with a care for wild landscapes and what they reveal to and of us – that ‘the utopia of love is completion to the point of stillness’. Since Jacquetta – my lover, wife, and friend of forty years – and I came together, the truth of that is what we sought, and what we found in the wild places through which we travelled.

Before meeting up with her again, crossing by chance the chasm of a twenty-eight-year sad divide, I was, I suspect, in the state that Robert Louis Stevenson describes in his ‘Night Among the Pines’ chapter from Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes:

even while I was exulting in my solitude I became aware of a strange lack. I wished a companion to lie near me in the starlight, silent and not moving, but ever within touch. For there is a fellowship more quiet even than solitude, and which, rightly understood, is solitude made perfect. And to live out of doors with the woman a man loves is of all lives the most complete and free.6

So we lived for a time what Matthew Arnold calls ‘the ideal, cheerful, sensuous, pagan life’. We married in a pagan ceremony down by the well in the cliffs at Braich y Pwll, with the raven, the seal and the chough as our witnesses. From my house at Llanrhaeadr ym Mochnant in the Tanat valley, in May-time before the bracken was long and the blossomy blackthorn trees confettied every hillside, we walked up to the pistyll four miles above the village, marvelled at the water efflorescing across dark strata before climbing on into the long strath of the Afon Disgynfa above and seeking out a bed in the heather from which to watch the stars come out and the moon sail from behind the bounding, low ridges. We were not going anywhere. We were coming to rest. Clung close under whatever covering of blanket or coat we had with us as the dew fell and the last hovering kestrel scythed valleywards. We watched the mottlings of shadow deepen and the rifflings of the breeze among the sedge, the jagged dartings of snipe, and we murmured minimally to each other of these things and snuggled a little closer and half-wakeful dreamed away the hours of the dark, and dozed in the sun of morning – this often and often, for the waincrat7 life was our joy and neither of us had found such sharing or such mutual joy before.

Many other such times in other places: one night on a Shropshire hillside, on a salient of sweet grass caverned into a thicket of gorse and facing west, from which we could see the sun’s descent, rolling along a Welsh hill horizon before it finally was drawn down into the elastic earth and the liquid of its fire spilled across the sky. As response to which I cut and lifted squares of turf, gathered sticks from the copse beneath and soon the bright flames illuminated the beauty of her face as it turned attentive to the sounds of the night: the last creaking flight of the late raven across indigo sky, hush of an owl’s wings, scurry of mouse and vole through dry leaf litter, and the snuffle and scrape of a lumbering badger among the trees.

Light and colour were her métier. From glass she created designs of exquisite simplicity, drawn from the gentle attention she bestowed continually upon the world. To be in her company was to enter a kind of trance of the consciousness of beauty. One morning we awoke in a little, sandy cradle we had discovered in the falling cliffs by Hell’s Mouth. We had lain there nightlong listening to the soft susurrus of small waves upon the sand. The grass of the overhanging dune that sheltered us caught at rays from the sun’s rising, and its matter became light, a latticed and filigreed gleam of silver, crosshatching the azure. Later the same day, walking the beach at Porth Oer, stretched prisms before the crystal waves gave us gleaming, transfigured patterns in the sand under ultramarine water, momentarily, repeatedly. ‘It’s all in the stilling, in the moment, and the moment’s eternal,’ she breathed, turning to me and back to the water again, watching with her artist’s eye this blessing of sight being obscured and renewed by each rolling wave.

In the stilling was where she found herself. I learned from her truly to come to rest within a landscape, open my eyes, and see. She had no interest in haste or achievement or distances, sought simply for the peace that comes when we are at one – with each other, with natural creation. I remember a day when I had been south to walk unfrequented hills, then drove back to meet with her again. We took bread and wine to a beautiful little river spilling down from the moors of longing, very quiet and unknown.

In its oakwood glen we sat on a shingle bank in the sunset, and I was communicating to her a picture from the morning’s paper of an armless, burned and bandaged child in Iraq – who had wanted to be a doctor, to help and heal, and who might now never master those skills, might never delight in the feel of his lover’s skin or the cool lightness of spring flowers, who would never hold in his own arms his firstborn child or dangle his fingers in a stream like the one by which we sat – the flyers who dropped the bombs that had maimed him invulnerable; the press snapping away in a sort of exultation, capitalizing on all his shock and loss…

She heard me out, my hand in her strong one, and through her quietude, her still presence, over a space of hours these things we saw: a dipper working the stream feet in front of us; the sun setting as a great red and rolling orb; a sturdy horse with a white blaze that came to the far bank and communed; a little owl that alighted on a branch within arm’s reach and peered, unperturbed. A bright half-moon shone down, a badger travelled across the field upstream in its gleam and two ducks scolded until it had passed; there was no human sound, no unnatural light; the stream pulsed on, the air very still, and a glimmer of frost settled across the moss and the bladed leaves from which more bluebells would soon rise. We felt the evil and the beauty of the world – no one kind and omniscient god, but an energy that splinters into these manifestations, and both perturbs and heals.

On a July day we drove down to the Radnorshire hills and by one of the mawn pools8 above Painscastle, remote from roads, on as calm and clear a night as I can remember, we made a simple camp and built a fire. So windless was it that the flame of a candle we had placed by the trunk of a Scots pine rose unflickering to map the seamed shadows of the bark. To her, these, and the green hachurings of the weed in the shallows of the pool, and the whiskery croziers of new bracken, and the streaked carmines and tangerines of the sky, were the palette where her imagination mixed and dwelt so lovingly. I have known magic in my life, but no woman so magical as this.

When we returned to Llanrhaeadr late on a Sunday evening after this night out on the Black Hill, we poured a glass of wine and came out of the house to walk down into the old, circular churchyard of the village. She stepped on a rock in a low wall around the forecourt and it rolled away from her. A previous man in her life had beaten her savagely about the head, and her corrective balance was gone. Her feet flew in the air, she smashed down on the rock, and shattered two ribs. Six months later another fall, in which she cracked a lumbar vertebra. After that, her skin took on an ashen pallor. Our going into the outdoors was curtailed, but still, whenever we could, we would enter the margins of wilderness and come to rest there, to observe and to see: in the rainforest of La Gomera, on the wild western coast of Vancouver Island, or at bluebell and scurvy-grass time along the Pembrokeshire Coast Path, the sea a shimmer beneath. With the death of my son, whom she dearly loved, our joy was crowded out by grief. To be in each other’s arms in the outdoors was our solace still, but she was forlorn and tired, physically and emotionally pained.

A fortnight after Will’s passing she was diagnosed with cancer, began chemotherapy, and bravely endured its discomforts and indignities and the loss of the glory of her long and auburn hair, which she, so womanly, took hard. The shrinking of our physical horizons focused her attention ever more acutely into the splendour of detail, and its meditative power. Tint and pattern of a fallen beech leaf of autumn consumed her for an hour and more, turning it this way and that, finally letting it fall. We went to the Caribbean, away from the rigours of home weather to give her warmth, and the towering cloudscapes and scintillating emeralds of humming birds and visitant presence of the blue-crowned motmot and a scampering, comical agouti, and brilliant, fractured trajectories of fireflies absorbed her in glimpses of the joy of this jewelled world.

Always the prognosis was darkening. In March, she stood at the end of the bed and our eyes met as my face registered anguish:

‘Why are you looking at me like that?’ she asked.

‘Because you are so very beautiful to me,’ I replied, and the unspoken knowledge passed between us that she was dying. She had surgery and was told that the chances of recurrence were overwhelming, of survival beyond a very few years minimal. In the event, mercifully, it would only be weeks. On a Tuesday night, I supported her to a crystalline, mottled rock where we would often sit, water in front, west-facing across waves of tawny, cloud-shadowed moorland. Next day she went into hospital for a regular cancer clinic, but was admitted immediately, put in a small room at the end of a ward on morphine and a drip, with blackbirds singing in the cherry blossom outside. On her last night she ordered me peremptorily to stop messing about tidying things, get on the bed and cuddle her as we listened to the evening chorus. I held her, caressed her, told her how dearly I loved her as she slipped into sleep, and beyond that, deep unconsciousness. Next day, peacefully, almost imperceptibly, she died.

That evening, sitting on the crystalline rock, the little lilac helium balloon that had floated above her bed was released. There was not a breath of wind, the curlews were calling from the marsh, and courting redstarts flitted in and out of the leafless branches of the ash. The balloon rose straight up for fifty feet, and then at great speed and on an unwavering course, it took off westwards. At the exact point and moment of its disappearing from view, a star came out, blinked once, and was gone.

3

Beach of Bones

Two hours’ drive, the fast ferry to Dún Laoghaire, and the long miles across Westmeath and Kildare brought me to Grainne’s house in Galway at that dangerous time of late afternoon. Years on from our last meeting, there was still the disconcerting glitter in her eyes, the dark hair, the conquistadores’ West-of-Ireland profile, the music of the accent, the rhythmic sway of body to words voiced almost as sacrament, and the rustle and glisten of her favoured silks. All of which I registered remotely somehow, as the stirrings of dim memory, something of the distant past from which I was now entirely dissociated, no longer either threat or allure. We went out to eat in a busy Italian restaurant in Salthill, drank wine and brandy into the small hours as she probed and compared my losses, always using the one as detriment to the other:

‘As a mother, Jim, I know how you must feel about Will. That’s the big one. Your partner dying – if she was your partner – that’s nothing. But to lose your child, and your first-born too, what’s worse than that…’

‘She was my wife, and it doesn’t work like that, Grainne – the loss becomes cumulative, you can’t separate out – or I can’t begin to yet. Maybe it’s different for a woman, with the child growing in her body those nine months and often more the end of biological imperative than of love and connection. But remember that I had the care of Will from his being three weeks old, sole legal custody of him from when he was two. I doted on him and had a passionate care for him; and yet I still can’t say, as you’ve done, that this loss is worse than that loss. There’s a different intimacy with your lover, a different communion, and its being taken away is just as desolating. I can’t see how comparisons are relevant. My loved ones are dead – that’s all I know.’

I fretted the remnants of the night away ill at ease in the spare room. We walked the ragged coast of South Connemara in a cold east wind – the wind that in Wales is called ‘gwynt o draed y meirwon’ – ‘wind from the feet of the dead’. We visited graves beyond the Coral Strand; sought out brisk music that bounced off me like hailstones from frozen skin in the pubs; went to see a film – Christopher Nolan’s backwards and disjunctive thriller on the nature of perception, Memento, with Guy Pearce as the amnesiac searching for clue and explanation to his wife’s death – the trickeries of which had Grainne ranting and me pondering. And I talked much and necessarily of Jacquetta, which was not music to Grainne’s ears and was received with barbed responses that could, had I been less exhausted and desolate, easily have inflamed into angry refutation and dispute. On the third night in her spare room, finally, after nine months in which there had not been a single night of unbroken sleep, my consciousness gave way to the peace of oblivion.

How long I had held to that state I do not know – perhaps hours, perhaps only minutes. What plucked me from it was awareness of urgent and wine-sodden breath panting at my cheek, and a wetness slathering rhythmically up and down my thigh. I leaped from the bed. There were words. Next morning I drove away west, circled around the mist-shrouded Twelve Bens by the shores of Lough Inagh and Kylemore Lough, and walked up Diamond Hill, which was free of cloud. From the summit I could look down Ballinakill Harbour and see Inishbofin, scan across Renvyle and the silver flash of Tully Lough to Inishturk, wildest and most remote of the Irish islands, where I’d had warm hospitality and welcome in past years, riding out there in a small island boat in a March gale from Roonagh Quay up in Mayo with The Flea tucked into my jacket as we bucked and slammed across the waves.

I came down from the hill and drank a pint of Guinness in Veldon’s Bar in Letterfrack, as Jac would have done, and always did when the opportunity presented itself. I used to tease – not knowing then of the cancer’s already having taken root – at how she retained her wraith-like figure whilst drinking more of the stuff than I could. And the taste of it brought the memories flooding back. Only a month before, we’d been together at the Academi Festival in Cricieth. I’d read from a recent book and interviewed a clutch of poets – Nessa O’Mahony, Chris Kinsey, Mike Jenkins. We’d dined in a rackety way with our raucous, intense, good friend Niall Griffiths and with reticent, decorous Colm Tóibín – a pairing made in comic-novel heaven. The strained and sniping interplay between the two of them, Scouse urchin and gay mandarin, was novelistic in itself, as though with hatchet wit and lancet tongues they’d battered straight out of one of Kingsley Amis’s acerbic late fictions.

We’d stayed up late in the bar of the Marine Hotel. Jac locked into an intense women’s conversation, concerned, anxiety-disclosing, heads bowed close, with my dear friend Sally Baker of the National Writers’ Centre for Wales, whilst I warbled and slurped away in Saturday-night Welsh-pub-style with Twm Morys and Iwan Llwyd, refilling glasses when called for, holding Jac’s hand all the while as our time slipped away. On the Sunday, in warm April sunshine, we’d sat on a sun-aligned bench, which is no longer there, by Cricieth’s West Beach and I’d gone to fetch her the biggest ice cream I could find from Cadwalader’s ice-cream parlour, which for once she couldn’t finish – never anything other than the biggest of ice creams for her, who could eat a litre pot at a sitting and often did, yet still looked as slim as when I first knew her at seventeen. On one of the several honeymoons Jacquetta and I had (at least one every three months for the rest of our lives she’d decreed as part of the marriage contract, and so it worked out) – this one in Vancouver – she’d come across a kiosk in Stanley Park near the Lions Gate bridge that advertised itself as selling ‘the best ice cream in the world’. So there and then she’d conducted a taste test and told the proprietor that his wasn’t as good as Cadwalader’s of Cricieth and he should get himself over there to try it. Also, Cadwalader’s sizes were larger. He gave her an outsize free one, of course, for that concluding sally and I, recognizing the game and seeing the need for reassurance that her charm still worked – which it did unfailingly and to my frequent amusement – drifted off with a wry smile to photograph the bridge, leaving the two of them to pat the innuendo lightly back and forth.