Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

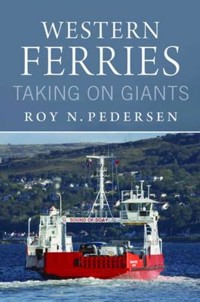

In the late 1960s, drawing on Scandinavian experience, Western Ferries pioneered roll-on roll off ferry operations in Scotland's West Highlands and Islands. This innovative company's original focus, was Islay, where its hitherto undreamt of frequency of service transformed that island's access to the outside world. The company's profitable and efficient operation was, however, deliberately sabotaged by heavily subsidised predatory pricing by the feather-bedded state owned competitor. This shameful policy, initiated at the highest political level, has been uncovered by recently released official correspondence held in the Scottish archives. The Islay service eventually succumbed, but the company's service across the Firth of Clyde between Inverclyde and Cowal, not only survived, but, in the face of many challenges, flourished to become by far Scotland's busiest and most profitable ferry route. Its modern cherry red ferries run like clockwork, from early till late, 365 days a year, employing some 60 people locally. It contributes much back into the community it serves including free emergency runs, whenever required, in the middle of the night.What made all this possible was the extraordinary dedication of a succession of enthusiastic, determined and above all colourful individuals. This is their story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 319

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WESTERN FERRIES

Born of a maritime family, Roy Pedersen’s former career with development agencies Highlands and Islands Development Board and Highlands and Islands Enterprise, where he pioneered numerous innovative and successful ventures, has given him a matchless insight into world shipping trends and into the economic and social conditions of the Highlands and Islands. He is now an author, proprietor of a cutting-edge consultancy and serves on the Scottish Government’s Expert Ferry Group.

OTHER BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Non-fiction

One Europe – A Hundred Nations

Loch Ness with Jacobite – A History of Cruising on Loch Ness Pentland Hero

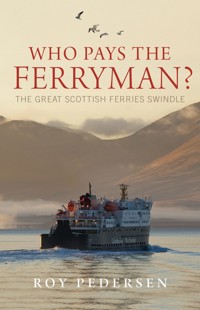

George Bellairs – The Littlejohn Casebook: The 1940s Who Pays the Ferryman?

Fiction

Dalmannoch – The Affair of Brother Richard Sweetheart Murder

First published in 2015 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Roy Pedersen 2015

Foreword copyright © Sir William Lithgow 2015

The moral right of Roy Pedersen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 270 2 eISBN: 978 0 85790 863 6

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow

This book is dedicated to the original Western Ferries pioneers:

John Rose, Sir William Lithgow, Peter Wordie and Iain Harrison and those that followed in their wake

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations and Maps

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1Busiest and Most Efficient

Chapter 2The Way It Was

Chapter 3New Ideas – Eilean Sea Services

Chapter 4Islay and Jura Options

Chapter 5Western Ferries Is Born

Chapter 6Expansion

Chapter 7Government Responses

Chapter 8Bid and Counterbid

Chapter 9The Clyde Operation Starts

Chapter 10Contrasting Modus Operandi

Chapter 11Competition Hots Up

Chapter 12Waverley

Chapter 13Oil and Troubled Waters

Chapter 14Hard Choices

Chapter 15Highland Seabird

Chapter 16Developments on the Clyde

Chapter 17Reorganisation

Chapter 18The Orkney Venture

Chapter 19Growth and Consolidation

Chapter 20The Deloitte & Touche Report

Chapter 21Self-Management

Chapter 22Europe Enters the Fray

Chapter 23Dunoon Debates

Chapter 24Tendering Shambles

Chapter 25Modernisation

Chapter 26Pressing the Case

Chapter 27Profits and Tax

Chapter 28The Gourock–Dunoon Tender

Chapter 29Two More New Ships

Chapter 30Community Relations

Chapter 31The MVA Report

Chapter 32Western Ferries Today

Chapter 33What Next?

Appendix:Fleet List

Bibliography

Index

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Crossing the firth with Michael Anderson in command of Sound of Scarba.

The author drives ashore from Sound of Scarba at Hunter’s Quay to interview Western Ferries’ Managing Director Gordon Ross.

First of the line. Sound of Islay is launched.

Sound of Islay leaving Port Askaig.

Sound of Gigha, ex Isle of Gigha leaving Port Askaig for Feolin.

Sound of Jura.

The fleet at Port Askaig.

Swedish practicality, Olandssund III.

Sound of Shuna (I), ex Olandssund IV.

Sound of Scarba (I), ex Olandssund III with MV Saturn in the background.

Sound of Sanda (I), ex Lymington.

Highland Seabird prepares to overtake Waverley.

Sound of Seil, ex Freshwater, as newly acquired.

Sound of Sleat, ex De Hoorn, leaving Hunter’s Quay.

Sound of Scalpay, ex Gemeentepont 23, at Kilmun.

Sound of Sanda (II), ex Gemeentepont 24, at Kilmun.

Sound of Scarba (II) at Hunter’s Quay showing the generous clear vehicle deck.

The new terminal layout at McInroy’s Point.

The new layout at Hunter’s Quay.

Sound of Soay emerges from Cammell Laird’s construction hall.

The fleet at Hunter’s Quay.

LIST OF MAPS

Western Ferries scheduled routes

The Overland Route

Upper Firth – Western Ferries and Calmac routes

Firth of Clyde – Western Ferries Routes, 1970s

FOREWORD

The lifeblood of the West of Scotland and Northern Ireland for much of history has been maritime. It was easier to travel the coast in a boat than hack across land. When the Lowland Crown sought to curb the Lordship of the Isles, the building of the Highland workboats, or birlinns, was banned, and communities could no longer get together freely. Centuries later, steamers brought public services onto set routes. In Inveraray, the town crier announced, ‘The Mary Jane will sail for Glascu the morrow’s morn, God and weather permitting. She will go the next day whether or no.’

When Western Ferries was born, islands were dying on their feet. The regular island services were state controlled, their technology moribund. The distilleries of Islay and Jura were having to bear delay and handling costs that no longer burdened their mainland competitors, where road transport carried goods and people from door to door.

There is no more dangerous monopoly than a monopoly of wisdom. It seemed obvious that there was room for an alternative to the methods of yesteryear to link up islands and coastal areas. The sea was no longer so much the ancient highway as a space to be crossed. Trucks and cars travel much faster than ships, so crossings had to be as short as possible, and ro-ro made turn-round speedy.

Owen Clapham on Islay and former Argylls brother officer Peter Wordie, a ship owner, got backers together and included me. The result was Western Ferries. The little Sound of Islay was ordered, primarily to carry malt and empty casks into the island distilleries and take whisky out, using terminals Western Ferries had to create for themselves. Carrying cars and passengers in the silent distilling summer season was an afterthought, but car users took to the first roll-on-roll-off service like ducks to water, as did the islanders and their mainland family and friends.

There was a lot of hard graft, generosity and a lot of fun, all made possible by a wonderful team and some very special characters. Jura, where I have spent a big slice of my life, was transformed by the Islay link. The old people wondered how cars could have got onto the island without seeing them coming! It was a novel experience that there was a service for the island that at that time was not taxpayer funded. We invented discounted books of tickets to benefit residents. The officers established the Sound Catering Company, and the skipper would butter the scones in the chartroom, whilst a vending machine could serve coffee and oxtail soup, which often ended mixed together in a cocktail in heavy weather.

I was very privileged to play a number of bit parts in those days when many ideas were becoming realities. Lithgows had consultancy remits, establishing the Hyundai shipyard in South Korea, and in Shetland for efficient short-crossing ferry links between islands. The National Ports Council, of which I was a member, was helping the Shetland Island Council to become harbour authority for the oil developments, a role Edinburgh, though more distant from Sullom Voe than it is from Whitehall, was most anxious to add to its empire. The Sound of Islay, with her reach ashore stern ramp, delivered the first waves of construction material to both Shetland and Orkney.

From day one the authorities were as uncomfortable with the Western Ferries home-grown island initiative as James VI would have been if we had launched a fleet of birlinns. The Secretary of State, an Argyllshire man, had told me the official view was that modern ferry services would result in people leaving islands for good. As a Jura proprietor manager, I was only too aware of the practicalities of the island economy and way of life.

Lithgow’s design consultancy, KMT, had worked up the ideas (which had to meet very strict UK construction regulations), and their Fergusons shipyard built the Sound of Islay (still in service in Newfoundland) for new berths in West Loch Tarbert and at Port Askaig, but she had to be able to berth also at traditional quays. In addition, the doubting authorities of the ‘Home Shipowners’ Finance Scheme’ also had to be persuaded that if the Islay project failed, the vessel would have an alternative market.

Islay and Jura’s demand for Western Ferries’ pioneering service was such that a second and more passenger-friendly ship was needed urgently. The Sound of Jura came from Norway, where ferry services were highly developed. For years we promoted the Norwegian idea of a subsidised road-equivalent tariff, particularly for freight. Government decided that as indigenous enterprise could meet demand without subsidy it should be left to get on with the job; the state operation should likewise be unsubsidised on the Islay route. For a while Western Ferries carried all the traffic. The state then re-introduced an open-ended subsidised service. Ministers were systematically briefed against ‘the upstarts’. The prospects of indigenous enterprise were blighted once more.

The ancient linkage of Kintyre and Antrim – North and South Dalriada – had already been re-established by the company. The Pollocks, founder backers, provided a site at Ballochroy that was to cut sailing time to Islay by half an hour, enabling a ship to make four sailings during the day and a night freight run to Antrim. Short crossings had been investigated for Mull, Arran, Loch Fyne, but Cowal could obviously do with a short, no-frills crossing. Necessity is the mother of invention. The revolutionary link span, today used throughout the world, was devised to satisfy a shareholder who insisted that if the Cowal venture was frustrated the berth could be towed away and used elsewhere.

Power corrupts. Politicians and public servants love power. Ensuring the dependency of communities on a publicly-owned service is irresistible, so understand island people’s anxieties that financial support for their life-lines could be cut if a private company provided the public service. They know Edinburgh’s track record over the centuries. Even when the Monopolies Commission investigated the Clyde–Argyll crossing they were fed state-operation figures which did not tally with reality. One has to be pragmatic in the face of such misinformation. There must be transparency in costs and in the benefits to the user. The state monopoly is not a commercial operation and cannot be exempt from Freedom of Information. What benefit is there in waste? The EU requires that subsidy is for the benefit of those served, not to cushion providers. There must be no discrimination, particularly on the basis of ownership.

Western Ferries were advised by Government that a replacement for their Jura Islay ferry was ineligible for a grant because it was not publicly owned, yet a 75 per cent grant was being paid for the state-owned boat to serve Cumbrae. The Argyll and Bute District Council was offered 25 per cent for a Jura boat, the resulting design of which was ill conceived. Unlike a public sector operation, a free enterprise like Western Ferries is able to buy and sell ships of efficient design and which can operate within the rules of the state ships’ regulatory body, from and to whom it likes. But what matters as much is the objective of a service; and it is a provider’s job to establish how best the objective can be attained. Governments woefully lack procurement expertise in specifying requirements: preconceived ideas all too often lead to tears.

I was deeply touched by a former UK Minister’s reaction to the finding that the state operator lost money on every route. In a supposedly radical newspaper I enjoy because it digs out the facts, he explained how he had hitherto been taken in by official briefing, spin and propaganda. He recalled too how growing up in Cowal had been transformed by Western Ferries as it enabled him and his friends to get to football matches and other events.

The hallmark of the British administrative class is technological illiteracy, manifest currently in Scotland in the eulogising of groundbreaking hybrid boats, yet such boats were being built in Greenock a century ago! Before even counting the cost of unsound expenditure, turning private money into public money and then back again to private benefit is incredibly wasteful, given all the processing, bureaucracy and overheads involved. Turning opportunities into problems is a poor substitute for the old virtues of thrift and ingenuity.

In years to come historians will try to fathom the extraordinary perseverance of Western Ferries. What a dedicated team created and what they do today is easily taken for granted. The blight of State intervention, spin and propaganda have frustrated beneficial development, and have denied islanders choice. Whatever has been the benefit in putting both of an island’s lifelines in the same pair of hands?

I am glad we were able to translate Western Ferries’ island DNA to serve Cowal. So many years since my leaving the company – after having had an overdose of Government intervention – it is a great privilege to have been asked to write a foreword for this book. In it Roy Pedersen recounts brilliantly the practical, financial and political difficulties that have faced Western Ferries over the years, and captures that unique pioneering and innovatory spirit that has enabled them to succeed against the odds. Their good work and good sense is an example to be very proud of, and an example that needs to be emulated.

Sir William Lithgow

May 2015

PREFACE

This book is the third in a trilogy about Scottish ferry operations. It tells the story of Western Ferries, Scotland’s most successful ferry operator. Drawing on Scandinavian experience, Western Ferries pioneered roll-on/roll off ferry operations in Scotland’s West Highlands and Islands. In fact the story of Western Ferries is that of three separate legal entities, but in practice the enterprise is one continuum in terms of personnel, ships, assets and operating principles.

This innovative concern’s original focus was Islay, where its hitherto undreamt-of frequency of service transformed that island’s access to the outside world. The company’s profitable and efficient operation was, however, deliberately sabotaged by heavily subsidised predatory pricing by the feather-bedded state-owned competitor. This shameful policy, initiated at the highest political level, has been confirmed by recently released official correspondence held in the Scottish archives.

The Islay service eventually succumbed, but the company’s service across the Firth of Clyde between Cowal and Inverclyde not only survived, but, in the face of many challenges, flourished to become by far Scotland’s busiest and most profitable ferry route. Its modern cherry-red ferries run like clockwork, from early till late, 365 days a year, employing some 60 people locally in Dunoon and Cowal. It contributes much back into the community it serves, including free emergency runs, whenever required, in the middle of the night.

As with my previous two volumes, Pentland Hero and Who Pays the Ferryman?, this volume is as much about enthusiastic, determined and above all colourful individuals who have risen to almost overwhelming challenges, as it is about ships and the communities to which they ply their trade. Like my other two volumes, this book also describes the reprehensible skulduggery of men in authority who sought to undermine the efforts of those who sought and demonstrated a better way of doing things.

It may be useful to put on record my motivations for writing these books. It is first and foremost a professional interest in advancing the social and economic well-being of Scotland’s island and coastal communities; it is secondly a lifelong interest in shipping and maritime affairs; and thirdly a desire to demonstrate good maritime practice while exposing inefficiency and the scandal of misjudged public policy. In pursuing these motives, I have sought to be fair and unbiased, although some of whom I have been critical may think otherwise.

Both Pentland Hero and Who Pays the Ferryman? received many glowing five-star reviews, although there was at least one accusation that I had been paid to write an unbalanced account that favoured private sector operators. It is true that I have held up Pentland Ferries and Western Ferries as examples of good practice, but the only payment I received from their authorship was the normal author’s royalties from my publisher. The judgement as to what to write was mine alone.

Writing Western Ferries – Taking on Giants has for me been a most agreeable task and in this account of the company’s history and prehistory, I have, as before, attempted to be fair, but have not pulled my punches where I believe censure is necessary. I hope readers will enjoy this account as much as (I have been told) they enjoyed the previous two books.

Roy Pedersen

March 2015

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a book of this kind would not have been possible without the help of numerous individuals. Some of these require special mention and thanks.

I am especially indebted to Gordon Ross, Managing Director of Western Ferries, and his fellow directors for their sponsorship and guidance in researching and writing this work. Gordon has been a fount of information and was able to source and make available a wealth of company material that would have been inaccessible to me otherwise.

In fact in all my dealings with the personnel of Western Ferries I have met with nothing but courtesy and helpfulness, for which I am extremely appreciative. I was especially pleased when Graeme Fletcher, the company’s Technical Director, arranged passage on the wheelhouse of Sound of Scarba under the care of her skipper, Michael Anderson. Michael was both informative on the operation of the company’s vessels and also supplied a number of the excellent photographs that supplement the text.

Then there is John Rose who patiently took me through the saga of Eilean Sea Services, Western Ferries’ precursor, and the early days of Western Ferries itself. For permission to plagiarise large parts of his unpublished essay, ‘How Roll on roll off Came to Islay and Jura’, I am very grateful.

It was another Western Ferries old timer, Arthur Blue, who four decades ago first introduced me to the practical and efficient way in which the Norwegians design and operate their ferries and how Western Ferries emulated their methods. Arthur’s anecdotes and general support have helped to enliven the story and for that I am much obliged.

One source that was of particular help in ensuring the chronology of events is correct is the excellent article on Western Ferries in 1996 by Ian Hall in Clyde Steamers magazine number 32. I was delighted to meet Ian a few years ago while cruising on the wonderful paddle steamer Waverley, and to deliberate on matters maritime.

Thanks are due also to Sir William Lithgow, for his pithy and forthright Foreword, and to Iain Harrison, Ken Cadenhead and Alistair Ross, who gave me useful pointers while I was undertaking my research.

I am most grateful to John Newth, who prepared the detailed particulars covering all the vessels in Western Ferries’ fleet past and present to form the fleet list which appears as an appendix to the text and for supplying his excellent photographs. Grateful thanks are also due to Jim Lewis, whose maps clarify the geographical setting of this account.

Of course this book would never have seen the light of day without the support and patience of Hugh Andrew and his colleagues at Birlinn, my excellent publishers. For that I am much indebted.

Finally I must thank Marie Kilbride who kindly agreed to proofread the various drafts as the book evolved. I have striven for accuracy, but if any errors have crept in, then the fault lies at my door and mine alone.

CHAPTER 1

BUSIEST AND MOST EFFICIENT

We have looked at ferry operations all over the world, but today our quest is much nearer to home. We are heading west on the M8 motorway from Glasgow towards Greenock and the Clyde Coast to study Scotland’s busiest and most efficient ferry service.

The day is fair. As we progress, the widening River Clyde comes into view to our right. The Clyde, they say, made Glasgow and Glasgow, in turn, made the Clyde, by dredging it to enable the great ships to dock in the heart of the city. Nowadays dredging has been curtailed; the great ships have gone and so have almost all of the famed shipbuilding yards. Sadly, no longer do Clyde-built and Clyde-owned ships dominate the world’s seaways.

On the far bank of the river, the morning sun highlights the Old Kilpatrick Hills, presenting a rural aspect that lifts the spirits and offers a foretaste of the grander scenery that awaits us. On the same north bank, just above water level, an electric train, bound for Helensburgh, hurries westwards to disappear behind the volcanic plug of Dumbarton Rock, the stronghold of the Britons of Strathclyde in ancient times.

Before we reach our goal, however, we pass successively through Inverclyde’s linear urban spread of Port Glasgow, Greenock and Gourock. Each has played an important part in Scotland’s industrial and maritime development and each has suffered, in the last half century, from the steep decline of that economic base.

John Wood’s yard in Port Glasgow built Europe’s first commercially successful steamship Comet in 1812 – the progenitor of all subsequent powered craft in these waters. At the time of writing, Ferguson’s shipbuilding yard, the very last on the lower Clyde to build merchant ships, faced difficulties, although it is hoped that the new owners will breathe new life into the business. In Greenock, gone is its once proud industrial might, based on sugar refining, engineering and ships. Something of the maritime tradition does fortunately continue in the form of a cruise ship and container terminal, a base for tugs and for Clyde Marine Services Ltd, an enterprising concern that operates a fleet of small cruise vessels and work boats. Gourock is more residential, a railway terminus and one-time base of the former Caledonian Steam Packet Company CSP, which operated its extensive Clyde steamer fleet from the railway pier. The pier is still the headquarters of the state-owned ferry monopoly, the David MacBrayne Group and its operating subsidiaries CalMac Ferries and Argyll Ferries.

We round Kempock Point, along Kempock Street with its shops and café, and then, on our right and to seaward, a grand vista opens up of mountains and fjord-like sea lochs. We take in the panorama. Ahead, across the widening firth are the hills of Cowal with its string of coastal settlements of Dunoon, Kirn and Hunter’s Quay, just to the right of which is the mouth of the Holy Loch with its own string of watering places. Further to the right and northwards is the mouth of dark Loch Long and at its head the craggy Arrochar Alps. Then right again and almost behind us are the lower rolling contours of the Rosneath Peninsula with its own waterfront community of Kilcreggan.

As we proceed past the suburb of Ashton and the Royal Gourock Yacht Club, our attention is drawn to a red-hulled ferry, as yet some way off, making its purposeful passage towards a landfall not far ahead of us. In a few minutes we reach the vessel’s destination well before its arrival. This is McInroy’s Point, the Inverclyde terminal for Western Ferries and Scotland’s busiest and most efficient ferry crossing. As we line up in the vehicle marshalling area, we notice that another red ferry has just departed from the terminal headed for Cowal.

We have time for a quick inspection of the terminal. It is a fit-for-purpose affair and most effective. The marshalling area is roughly triangular, following the outline of the rocky headland that is McInroy’s Point. There are two ferry berths with their aligning structures and link-spans – the hinged bridges that enable vehicles to be driven on and off at any state of the tide. One berth is set to the north-east and the other at an obtuse angle to the sou’-sou’-west. In this way the vessels can berth in all but the very worst of weather conditions, irrespective of wind direction.

Our ship, Sound of Scarba, one of the four near-identical members of the Western Ferries’ fleet, is now approaching and as she noses into the north-east berth, a sailor stands in the bow with a long pole to engage a valve on the shore. This action causes air to be vented from a submerged floatation chamber so that, as buoyancy reduces, the link-span lowers onto a ledge built into the vessel’s bow and engages two locking teeth. In this way the link-span is locked on to the ship so that, even in a heavy swell, it can rise and fall with the heave of the ship – a very safe arrangement.

Sound of Scarba is quickly berthed – no fuss, no bother. Vehicles and foot passengers stream ashore. Among the vehicles is a McGill’s coach that provides a through service from Dunoon to Glasgow. We must regain our car, however, to be ready to drive aboard because these Western Ferries folk don’t hang about.

We follow the line of vehicles on to the ferry’s vehicle deck and are directed to our place. We alight and make ourselves known to the purser who is issuing tickets. The company has granted us the treat of travelling in the wheelhouse. On reaching this privileged position we are welcomed by the skipper, Michael Anderson, who gestures for us to enter his domain. Michael Anderson, now in his 35th year with Western Ferries, started with the company in 1980 as a deckhand and worked his way up to master. He is also an accomplished photographer.

He explains the operation of the ship. The wheelhouse is equipped with the normal GPS and radar navigation aids, but the means by which the vessel is controlled are somewhat unusual. As with the other vessels in the fleet, Sound of Scarba is propelled fore and aft by Rolls-Royce azimuth propulsion units that can turn through 360 degrees. These units are controlled from the wheelhouse by two joysticks that are simply rotated to direct each propulsion unit to provide thrust in the desired direction. This arrangement renders Sound of Scarba and her sisters highly manoeuvrable such that they can pirouette in their own length or move sideways. The joysticks also act as throttle controls – all in all a simple but highly effective control system.

As we talk about matters maritime and personal, the other members of the travelling public either remain in their vehicles or make for the covered saloon, equipped with seating and toilets, or, as the day is warm and sunny, they head for the upper deck where they can better enjoy the view and see what’s going on as departure time approaches.

There is a lull of a few minutes and we note that there is a goodly cross section of vehicle types on deck – cars, vans, motor bikes, a couple of camper vans and one large artic. Then with Michael at the controls, a signal is given, there emanates from below decks a rumble of engines. The Sound of Scarba disengages from the link-span and we’re off on the 20-minute passage across the firth to Hunter’s Quay. As we clear the terminal we admire the unfolding panorama. To the south the Firth of Clyde opens up, framed by the distant and majestic Arran mountains.

As we progress, we espy another Western Ferries vessel heading our way. She passes us to port heading for McInroy’s Point. Such is the frequency of the service that it acts as a vital almost continuous conveyor connecting the road systems of the central belt of Scotland with Cowal and greater Argyll beyond.

As we ponder this, a small passenger vessel passes by our stern. She is Argyll Flyer, operated between Dunoon Pier and the railhead at Gourock by Argyll Ferries. Argyll Ferries is a subsidiary of the David MacBrayne Group and this subsidised passenger service is successor to the vehicle ferry service formerly operated by Caledonian MacBrayne and latterly by Cowal Ferries.

Soon Sound of Scarba closes in on the Cowal shore and Western Ferries’ Hunter’s Quay terminal and we are instructed to return to our cars ready to disembark, so we thank and bid farewell to the skipper. Our vessel docks and vehicles stream ashore heading for their ultimate destinations. We do not follow them, for Hunter’s Quay terminal is where Western Ferries’ headquarters are located and we have an appointment with Gordon Ross, the company’s managing director. We enter the building, which is crisp and businesslike, but by no means grand. We present ourselves at reception and are taken through to the MD’s office.

‘Ah, come in and welcome. I have been expecting you.’

This is the point from which the amazing saga is expounded of how, against a sustained official campaign to undermine it, Western Ferries has become the operator of Scotland’s premier ferry route.

Before we consider the origins of Western Ferries as a corporate entity, it is useful to go back in time to Cowal of old and to consider how a key commodity was transported across the same stretch of water on which we have just made passage.

CHAPTER 2

THE WAY IT WAS

Cowal (Gaelic Còmhghal) is a rugged peninsula extending some 40 miles from north to south and connected in the north to the rest of mainland Scotland by a mountainous isthmus dominated by the Arrochar Alps. This isthmus is traversed by a hill pass known as the Rest and be Thankful, through which runs the A83. The A815 links with the A83 to provide the only and very circuitous access road from lowland Scotland to Cowal and its principal settlement of Dunoon.

To the east, Cowal is separated from the lowlands by fjord-like Loch Long and the widening Firth of Clyde. To the west, Loch Fyne, Scotland’s longest sea loch, divides Cowal from Mid Argyll, Knapdale and Kintyre, beyond which lie Islay, Jura and the other isles of the Hebrides.

The eastern coast is riven by two sea lochs – Loch Goil and the Holy Loch. Two further sea lochs – Striven and Riddon – penetrate Cowal’s southern fringe whose two extremities Toward Point and Ardlamont Point almost embrace the Isle of Bute. This populous island is separated from Cowal by the narrow and winding Kyles of Bute.

From time immemorial, Cowal was inhabited by a Gaelic-speaking race and by the late sixth century the territory came under the sway of Cenèl Comgall, the kindred of Comgall, from whom Cowal derives its name. Comgall was a grandson of Fergus Mòr mac Errc, the first recorded ruler of the Scottish kingdom of Dalriada and ancestor of the present Queen Elizabeth.

This is not the place to relate the history of Cowal, other than to mention that, like many another Highland province, periodic clan strife was endemic. Clan Lamont dominated Cowal for many centuries, the early chiefs being described as Mac Laomain Mòr Chomhghail uile – The Great MacLamont of all Cowal. Then in 1646, in the Dunoon Massacre, over two hundred Lamont clansmen, women and children were murdered by Campbells, and over time the clan was dispersed. According to tradition, my own family on the distaff side claim descent from dispossessed Lamonts.

In subsequent centuries, as more settled conditions prevailed, one trade above all others came to dominate the economy of the Highlands and Islands. That trade was the rearing of cattle and the droving of them to the southern markets. For nearly 200 years, from the second half of the seventeenth century, throughout the eighteenth century, and into the early nineteenth century, droving flourished. Droves were assembled in the spring for eventual sale at the big trysts. As they progressed slowly across country the cattle had to be managed skilfully to avoid wearing them down. It was a hard and, at times, dangerous life, but the hardy Gaels, with their warlike, raiding past, were perfectly suited to it.

Where a drove had to cross a short stretch of water, cattle would be swum across a sea loch or sound as from Bute to Cowal at Colintraive (Gaelic Caol an t-Snaimh – the swimming narrows). In the case of islands that were further offshore or wider firths, it was necessary to ferry the beasts. To minimise shipping costs in such cases, the shortest feasible crossing was selected.

The contemporary economist Adam Smith explained:

‘Live cattle are, perhaps, the only commodity of which transportation is more expensive by sea than by land. By land they carry themselves to market. By sea, not only the cattle, but their food and their water too must be carried at no small expense and inconveniency.’

Such a ferry existed to cross the Firth of Clyde, where it was narrowest, between Cowal’s main settlement of Dunoon and the Cloch on the Renfrewshire shore.

With the peace that followed the end of the Napoleonic wars, the world was set for unprecedented change. Henry Bell’s pioneer steamboat Comet of 1812 was soon joined on the firth, and in more distant waters, by other and more efficient steam-driven vessels. As this newfangled mode of conveyance developed, it became more economic to ship livestock (and people, goods and mails) all the way from island or coastal communities to mainland urban centres or railheads by steamship. The long cattle droves and drover ferries fell out of use.

Then with the dawn of the twentieth century, the steamship itself and even the railway faced a new challenge. From its sputtering and smoky beginnings, the emergence of the motor vehicle had, by mid-century, become a near-universal means of moving people and goods.

Of course, island and peninsular communities were still connected by steamer services, but these were gradually concentrated on fewer piers with more convenient, economic and less polluting motor bus and lorry services connecting with the rural hinterlands. Where ferries had existed for many years to enable travellers to cross narrow sheltered waterways, some of these were adapted to carry one or more motor cars, typically employing a turntable equipped with hinged ramps to enable cars to drive on and off. Transporting a vehicle over more exposed seaways, however, necessitated lifting it by derrick on to a steamer’s deck and offloading by the same means at the destination. In some cases, when the tide was suitable, cars were driven on and off along precarious planks.

In some parts of the world, even when the motor vehicle was in its infancy, enterprising operators developed vessels that motor vehicles could drive on and off at any state of the tide, using specially adapted terminals equipped with a hinged bridge (link-span), to facilitate the ship to shore connection. Although an early pioneer, Scotland was slow to adopt this technology.

In the inter-war years, seagoing drive-on drive-off shuttle vehicle ferries were instituted on the Firths of Tay and Forth. In the west, however, the more cumbersome practices prevailed of derrick loading or driving vehicles aboard precariously along planks, despite ambitions in some quarters for something better. In 1930, in an attempt to explore a more modern approach, Dr Robert Forgan MP asked the Secretary of State for Scotland what steps had been taken by the government to ascertain the practicability of a motor ferry between Dunoon and Cloch.

There was little comfort from the Minister, Herbert Morrison, who responded dismissively: ‘I have been asked to reply. The proposal to establish a motor ferry between Dunoon and Cloch has not been brought to my notice by the local authorities concerned. I have ascertained, however, that the project has been discussed by the Dunoon Town Council and the railway company, but that it is not likely to mature.’

Further pressure on this matter, however, during the thirties must have awakened fears within the London Midland and Scottish Railway Company (LMS) that, if they didn’t do something, someone else might introduce a vehicle-carrying service, thereby undermining the railway company’s virtual monopoly on the firth. In fact by 1937 some 1,000 cars were carried between Gourock and Dunoon, using planks as tide permitted. By 1939 the LMS Steam Vessels Committee considered design options for a car-carrying vessel to be employed between their railhead at Gourock and Cowal, but the war intervened and these plans were shelved.

Further south, because of the huge increase in demand for conveying cars between Scotland and Ireland on the Stranraer–Larne route, the LMS commissioned Princess Victoria in 1939, the first British purpose-built seagoing passenger and car ferry. She could take 80 cars, loaded over the stern via link-spans. Sadly the Princess Victoria was lost early in the Second World War, striking a mine and sinking with the loss of 34 of her crew. After the cessation of hostilities, a replacement Princess Victoria was introduced along similar lines.

Another scheme that had been curtailed by the war was a proposal for a vehicular ferry across the narrowest part of Kyles of Bute between Rhubodach (Bute) and Colintraive (Cowal). Again the LMS sensed a threat and opposed the scheme, but in 1950 the private Bute Ferry Company Ltd inaugurated such a service, initially with a series of former wartime bow-loading landing craft. Cars were loaded and discharged straight onto the sloping beach at either end of the crossing.

It wasn’t until 1954 that the nationalised British Transport Commission introduced three side-loading vehicle ferries, Arran, Cowal and Bute, fitted with electric lifts or hoists to enable motor vehicles to be driven on and off at any state of the tide. This was an advance on former arrangements for handling vehicles, albeit a slow and cumbersome procedure. The rationale was that side loading with hoists permitted the use of existing piers, thereby obviating the need for construction of link-spans and aligning structures. The main duties of the vehicle ferries were shuttle services between Gourock and Dunoon, Wemyss Bay and Rothesay (Bute), and to Arran and Millport on the Great Cumbrae. In the same year as these new ships were brought into service, all the Firth of Clyde railway vessels were brought under the banner of the state owned CSP, originally a subsidiary of the Caledonian Railway. A fourth and larger hoist-loading vehicle ferry, Glen Sannox, was added to the Clyde fleet in 1957 for the Arran run.

In 1964 the hoist equipped side-loading principle was extended to the West Highlands and Islands when three new vehicle ferries, Columba, Clansman and Hebrides