Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

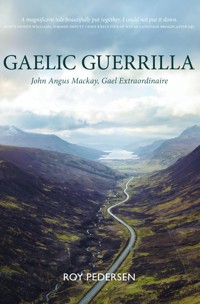

This is the astonishing story of John Angus Mackay, an islander from a humble background who achieved what others regarded as impossible. Through his tireless efforts, the Scottish Gaelic language and culture has turned a corner, and the number of young Gaelic speakers is increasing. Perhaps his most evident achievement came after a long, dogged and forensically focused campaign for the Gaelic television service against huge establishment resistance. At times, the channel now attracts viewership figures well in excess of the total number of Gaelic speakers in Scotland. But that is only part of John Angus' story: his courage to overcome disability, his contributions as a gifted teacher and his pivotal role in advancing community co-operatives in his native Lewis are all part of what he has achieved.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ROY PEDERSEN was born in Ayrshire and brought up in Aberdeen where he graduated from the University of Aberdeen with an ma in Geography and Economic History. After a brief spell in London, where he created and published the first and bestselling Gaelic map of Scotland, he has spent most of his working life based in Inverness. There he pursued a successful career in the economic, social and cultural development with the Highlands and Islands Development Board and its successor, Highlands and Islands Enterprise. In the course of this career, he was the original architect of the ferry charging system, Road Equivalent Tariff (ret). He was also intimately involved with the community co-operative scheme and revival of Gaelic including acting as Development Director of Comunn na Gàidhlig. More recently he has been proprietor of a consultancy business covering the diverse fields of transport and cultural development and has served as a Highland councillor. He writes, publishes, speaks and broadcasts on a variety of issues connected with world affairs and with the history, present and future development of the ‘New Scotland’ and its wider international setting.

He is Chair of Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba (Gaelic Place Names of Scotland) and he specialises, among other things, in maritime issues, serving on the Scottish Government’s Ferry Industry Advisory Group.

JOHN ANGUS MACKAY was born in Shader, Barvas on the west side of the Isle of Lewis in 1948. He was educated ‘painfully’ at Airidhantuim Primary School and the Nicolson Institute in Stornoway. He graduated with an MA degree from Aberdeen University and then gained his teaching qualification at Jordanhill College of Education in Glasgow. He also subsequently gained a Masters in Media Management at Stirling University. His varied professional career evolved from Sales Rep for DC Thomson, secondary teacher in Glasgow where he rose to assistant principal teacher of English, after which he returned to his native Lewis as community co-operative field officer with the Highlands and Islands Development Board and subsequently Senior Administrative Offices responsible for that organisations Western Isles activities. He was then appointed founding CEO of Comunn na Gàidhlig, CEO of Gaelic Television Service, serving also as Chair of Acair Publishing, the Gaelic college Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, An Lanntair multi-media arts venue and Western Isles Heath Board. If that was not enough, he was until recently an active crofter and now spends part of each year in his beloved Italy.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Non-fiction

One Europe – a Hundred Nations (Channel View Books, 1992)

Loch Ness with Jacobite – A History of Cruising on Loch Ness (Jacobite, 2007)

Pentland Hero – The Saga of the Orkney Short Sea Crossing (Birlinn, 2010)

George Bellairs – The Littlejohn Casebook: The 1940s (self-published monograph, 2010)

Who Pays the Ferryman? – The Great Scottish Ferries Swindle (Birlinn, 2013)

Western Ferries – Taking on Giants (Birlinn, 2015)

The Pedersen Chronicles – A Family History of the Pedersens of Ardrossan (For the Right Reasons, 2018)

Fiction

Dalmannoch – The Affair of Brother Richard (For the Right Reasons, 2012)

Sweetheart Murder (For the Right Reasons, 2013)

The Odinist (For the Right Reasons, 2019)

First published 2019

ISBN: 978-1-912387-71-7

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Roy Pedersen 2019

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface

List of Acronyms

A Modern Miracle

Community Roots

The Young John Angus

Cabadaich 1: Nuair a Bha Mi Òg Blethers 1: When I was Young

Stornoway

Alma Mater

The School of Hard Knocks

Glasgow

HIDB

Back to Lewis

The Co-Chomuinn

Diverse Dealings

Promotion

Other Developments

Italian Interludes

Cabadaich 2: Bella Italia Blethers 2: Italy

Cor na Gàidhlig

Comunn na Gàidhlig (CNAG)

Gaelic Education and Arts

Gaelic Broadcasting Evolution

The Magic Box

Change of Tactics

The Lion’s Den

Cabadaich 3: Mun Cuairt a’ Chagailte Blethers 3: Around the Hearth

Cento Veljanovski

Nobbling Ministers

Clinching the Deal

The After Eights

A University for The Highlands and Islands

A Troubled Transition

Comataidh Telebhisean Gàidhlig (CTG)

Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE)

On Air

Widening Connections

Digital Developments

Digital Foothold

Scheduling and Financial Difficulties

Assorted Activities

Raising the Stakes

Cabadaich 4: Foghlam Fad Beatha Blethers 4: Life-Long-Learning

Goals Achieved

BBC Alba

Health Board

Bòrd na Gàidhlig

The Legacy

A Well-Deserved Accolade

Cabadaich 5: Prìomh Threòraichean Blether 5: Main Influences

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

IT IS NORMAL for an author to thank numerous individuals who have helped in bringing their text into being. In this case the list is relatively short. The one individual above all who merits a very special thanks is John Angus Mackay himself. He was unstintingly generous with his time in relating evening after evening the amazing episodes of his life. On John’s behalf, I must also thank Sarah and Donnie Macdonald and his uncle Norman Mackay for sharing their research into the history and torpedoing of the armed merchant cruiser F94 Salopian on which John’s father served alongside Norman’s father John.

Thanks are also due to John’s son Derek for making available his History of Gaelic Radio Broadcasting by the BBC, to Leighton Andrews, now Professor of Practice in Public Service Leadership and Innovation at Cardiff Business School, for crucial detail on aspects of the lobbying challenges that John faced in securing funding for the Gaelic television service, as well as to John’s wife Maria who sourced several photographs and illuminated a number of episodes that John had skirted over, particularly with regard to their mutual Italian experiences.

The photographic illustrations were culled from a number of sources, many from my own or John’s collections, others are credited where the source is known.

I must of course record my grateful thanks to my publisher Gavin MacDougall of Luath Press and his staff for enabling the extraordinary achievements of John Angus Mackay to be recorded for posterity. As the book was the distillation of countless conversations between John Angus and myself, Gavin suggested that we exemplify a few of these conversations. While this involves some repetition, John and I have provided such examples in the form of five Cabadaich (Blethers) sprinkled throughout the text.

I also thank Marie Kilbride, who was an invaluable sounding-board as the text progressed and John Storey, son of our mentor, the late Bob Storey, who proofread the draft manuscript and uncovered and corrected many a factual, typographical and grammatical blunder. The responsibility for any remaining errors that may surface is mine alone for which I hope I will be forgiven.

Preface

IT IS MY privilege that John Angus Mackay has been a colleague and my very good friend for more than two score years. This is his story; that of the ultimate Gaelic guerrilla (oed definition: ‘Guerrilla, noun, a member of a small independently acting group taking part in irregular fighting, especially against larger regular forces’). It was Gaelic writer and broadcaster, the late John Murray of Barvas, who first likened John Angus’ regular forays from the Western Isles to Westminster as guerrilla tactics – rather like an old-fashioned creach or Highland raid.

That was John Angus’ working life to a T. His fight to save our rich and venerable Gaelic tongue and its culture was not of the military kind, but instead utilised psychology, subterfuge, persuasion, passion, tenacity and, above all, courage in achieving its ends. In pursuing this struggle, John was not just one of the small and committed group that turned round the cause of Gaelic against almost impossible odds; he was the pivotal lead figure during the critical few decades in which a thousand-year history of persecution and decline, instigated by a hostile and powerful establishment, was halted and, if the momentum is maintained, it is hoped, reversed.

Before John’s unique and vital role in this remarkable turnaround is forgotten, I just had to put it on the record. This book is the result. Whilst telling the story of one individual, there is no denying the fact that many individuals and organisations have made very significant contributions over the years to supporting the Gaelic language. This book seeks to illustrate the change in institutional attitudes towards, and support for, Gaelic which created the context in which John Angus Mackay’s efforts, with the help of others, achieved what had previously seemed impossible. It’s just a pity that we don’t have more John Anguses.

Of course, as the saying goes, no man is an island and that is no less true of John Angus. His skill lay in drawing on the achievements and efforts of other individuals and organisations in creating an environment in which his own efforts could get results. Among the key institutions are An Comunn Gàidhealach who for decades kept the cause of Gaelic alive. Comhairle nan Sgoiltean Araich, CLI and the Gaelic college Sabhal Mòr Ostaig undertook pioneering work in pre-school and adult education while the Bilingual Education Project in the Western Isles paved the way for Gaelic medium education. The Gaelic Books Council helped to keep Gaelic writing and publishing alive, while the fèis movement co-ordinated by Fèisean nan Gàidheal and the initiatives of the National Gaelic Arts Project created a foundation for the development of the confident young talent that today act as such splendid international ambassadors for Gaelic.

Individuals who drove the cause forward are too numerous to mention and many kept a low profile, working effectively, but unsung, in the background. A few, however, stand out. Brian Wilson’s advocacy for community co-ops on the Irish model was taken up by Ken Alexander, Chairman of the Highlands and Islands Development Board (HIDB). The model was skilfully adapted by the HIDB’s Bob Storey, thereby creating the career opportunity which gave John invaluable experience in community work and dealing with institutions. This experience was to stand him in good stead in tackling the immense challenges of managing the co-op programme and HIDB’s Stornoway office, Gaelic development through Comunn na Gàidhlig and the Gaelic Television Committee, rescuing the Western Isles Health Board and finally further advancing Gaelic as CEO of Bòrd na Gàidhlig. Of these individuals, a special personal debt of gratitude is due to the late Bob Storey, who not only mentored John and me, in the art – and it is an art – of community development, but set a standard of integrity and discipline that we have tried to emulate, not always successfully on my part.

In the national political arena, cross party-political support for Gaelic was, and still is, an important factor. Special credit must, however, be given to Malcolm Rifkind for assiduously pursuing the case within a sceptical Government, and in the face of Treasury opposition, for the creation of the Gaelic Television Fund. At the regional level, local authorities, came to play a vital role, most notably Highland Regional Council, Comhairle nan Eilean (Western Isles Council) and Strathclyde Regional Council, the latter being influenced by the Labour Party Gaelic Policy which had been drafted by Brian Wilson. And, after considerable persuasion, the broadcasters BBC, Grampian and Scottish Television also took up the Gaelic cause to incalculable positive effect.

Notwithstanding John’s guerrilla capabilities, one secret of his success was his ability to work within the system, even when the system was ranged against him. When the system became too obdurate or political routes failed, however, alternative means were adopted. For example, the possibility of a hunger strike and the response to the minister who suggested that the Gaels lacked the fire of the Welsh – ‘Are you inciting us to arson, Minister?’ – opened closed minds. So the willingness to consider more extreme measures, implied or intended, demonstrated that the Gaels might not have been as quiescent as they were, had things not panned out as positively as they did.

Anyway, my job as scribe has been to put John’s amazing story into written form. To save the blushes of some individuals, a number of the most hilarious, or alternatively most gut-wrenching episodes, could not be included, but those episodes aside, what has been recorded is a cornucopia of adventure that would fulfil the lifetimes of several lesser beings.

I hope you enjoy the saga of the Gaelic guerrilla.

Roy PedersenSeptember 2019

List of Acronyms

BBC:

British Broadcasting Corporation

BEA:

British European Airways

BNG:

Bòrd na Gàidhlig

BPS:

bits per second

CBE:

Commander of the British Empire

CEO:

Chief executive officer

CLI:

Comunn an Luchd Ionsachaidh (Gaelic adult learners organisation)

CNAG:

Comunn na Gàidhlig

CNSA:

Comhairle nan Sgoiltean Airich (Gaelic playgroups organisation)

COSLA:

Convention of Scottish Local Authorities

CTG:

Comataidh Telebhisean Gàidhlig (Gaelic Television Committee)

DCS:

Distinguished Service Cross

DG:

Director General

DSO:

Distinguished Service Order

EIS:

Educational Institute for Scotland

FOI:

Freedom of information

GME:

Gaelic medium education

GMS:

Gaelic Media Service/Seirbheis nam Meadhanan Gàidhlig

HIDB:

Highland and Islands Development Board

HIE:

Highland and Islands Enterprise

HMI:

Her Majesty’s Inspector (of Schools)

HMS:

His Majesty’s Ship

IBA:

Independent Broadcasting Authority

IDP:

(European) Integrated Development Programme

ITC:

Independent Television Commission

ITV:

Independent Television

MP:

Member of Parliament

MSP:

Member of the Scottish Parliament

NHS:

National Health Service

NTL:

National Transcommunications Limited

OBE:

Order of the British Empire

PA:

Personal assistant

RN:

Royal Navy

RNR:

Royal Naval Reserve

RTD:

Retired

S4C:

Sianel Pedwar Cymru, meaning ‘Channel 4 Wales’

SCU:

Scottish Crofters Union

SDN:

S4C Digital Networks

SMO:

Sabhal Mòr Ostaig (Gaelic college)

SMT:

Senior Management Team

SNP:

Scottish National Party

STV:

Scottish Television

TG4:

Irish Gaelic television channel

UHI:

University of the Highlands and Islands

VAT:

Value Added Tax

VHF:

Very high frequency

A Modern Miracle

OF THE MULTITUDE of television channels now available to us, one of the most fascinating is BBC Alba. This channel, which was launched in 2008, is watched regularly by over half a million viewers, yet, astonishingly, it is provided for Scotland’s small and dispersed community of just under 60,000 Gaelic speakers.

It seems that it is BBC Alba’s quirkiness that has attracted this unusually large and diverse viewership. Of course, as might be expected, a channel aimed at this small linguistic minority covers a mix of Gaelic music, news, current affairs, entertainment, education, religion, children’s programming, sport, drama and documentaries. The channel is normally broadcast between 5.00pm and midnight. But BBC Alba is far from inward looking. It regularly covers major sporting events, including top level Scottish professional football and other major sporting events. It features regular and highly popular Country and Western fare and the unique Eòrpa Gaelic current affairs programme, which uncovers otherwise unreported political, social and cultural issues across Europe – a format not found on any other channel.

The station is also unique in that it is the first channel to be delivered under a BBC licence by a partnership and is also the first multi-genre channel to come entirely from Scotland and with almost all of its programmes made in Scotland. As a means of broadening its reach, most programming features on-screen English subtitles although, for reasons of language development, children’s programmes are not subtitled.

What is so remarkable about all this is that until recent years, it was commonly thought that the Scottish Gaelic language was in such steep decline that it would be extinct within a couple of generations. And it is true that, while in the 12th century Gaelic was the language of almost all of Scotland and the tongue of kings, court and scholarship, it, and the rich culture it carried, had subsequently been the focus of relentless official policies aimed at its extermination. Such was the success of this sustained ‘ethnic cleansing’ that, towards the end of the 20th century, the transmission of the language to the next generation was approaching the point of no return. The ancient language, it seemed, was doomed.

Then something amazing happened – a miracle one might say. Through the actions of a small group of individuals, acting in concert, the process of linguistic destruction was challenged. New means were created to rebuild that which the powers-that-be had sought so long and so hard to destroy. By the first decade of the 21st century, the Scottish Gaelic language and culture was turning the corner. The number of young Gaelic speakers was on the increase.

How this was achieved will be described in the pages of this book but, in a nutshell, it involved achieving community, institutional and cross-party-political support for new policies and organisational structures, to aid the development of Gaelic medium education, promotion of Gaelic arts and culture and, to support all this, the creation of a Gaelic television service. The unexpected success of these efforts has silenced many detractors.

Many individuals have contributed to this linguistic and cultural renaissance. One man, however, stands out. Without his heroic efforts, a whole range of key Gaelic development initiatives could never have achieved the success they have. The most audacious of these initiatives, and against huge odds, was the campaign for a Gaelic television service, summarised by Brian Wilson in the West Highland Free Press as a ‘…textbook lobbying exercise’. The man in question has an unlikely pedigree. He comes from a humble rural Hebridean background, from childhood short-sighted, hard of hearing and often lacking in self-confidence; yet his courage, intelligence, humanity, political nous, people skills, wit and steely resolve were such that, what lesser beings regarded as impossible, he made possible. That man is John Angus Mackay.

Community Roots

LOWER SHADER is a crofting township on the west side of the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis and it was there in the early years of the 20th century, at Newpark, Lower Shader, that the Mackay household dwelt. The address was later known as number 43. The head of the household was Roderick ‘Rodaidh’ Mackay. In the late 1890s, he had enclosed the land at Newpark and renovated the old school building there to create a family home. His wife Annie bore him six children. Two girls Annie and Catherine followed the seasonal herring fishery from Shetland to Yarmouth; another, Peggy, was a nurse. Of the boys, John died as a result of an accident at a relatively young age, while Donald emigrated to America. Then there was Alexander Mackay, more commonly known as Ailig Rodaidh, or to give him his Gaelic sloinneadh: Alasdair Ruairidh Bhig ’An Bhàin. Like many another young Lewisman in the 1920s, Alexander Mackay followed his brother and went to the United States in 1929 to seek a better life.

At first, he found work as a sailor on the Great Lakes, but before long he got a job in Detroit with the Ford Motor Company. Even after the Great Depression struck, he was fortunate enough to keep his job, latterly as an engine polisher. That was Alexander’s job – a dream job in many ways – but for all that, with the gang-warfare that was rife at the time and then the Great Depression, America was not the land of milk and honey that it had promised to be a decade earlier.

In 1934, Alexander Mackay decided to come back home to Lewis. He had probably been carrying on a correspondence for some time with Mary Macdonald who was then working in Glasgow as cook to the family of a professor in medicine at that city’s University. In the last year of primary school, Mary had gained a bursary to go to school in Stornoway. When she came home all excited and told her mother, the response was: ‘But who will help look after the cattle?’ And that was the end of that. Years later, John was to have a similar experience with his mother causing him to sidetrack his ambition in similar circumstances.

Alexander and Mary married in 1935. Initially on return home, Alexander bought a loom and, whilst working the land, he weaved Harris Tweed, at times cycling to Stornoway for 16 miles to pick up the wool and cycling back to Shader. As was commonplace among the men of Lewis’ west side, Alexander enrolled with the Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) which entailed the pleasant and valuable diversion of periodic paid training sessions at Chatham in Kent. As events will reveal, the training and discipline gained was to prove invaluable.

The couple’s first son, Angus, was born in 1937; the second, Roddy, in 1939. Alexander also created a family home by building on to the side of his own father’s house, a task that was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War.

War inevitably meant call-up to serve King and country and although it seems almost unbelievable to us today, the 1939 to 1945 War Roll of Honour Ness to Bernera records that no less than 50 men and one woman from 27 homes in the village of Lower Shader served – including two homes which each gave four men, and six which each gave three men. Three gave their lives, including one of the five who were Prisoners of War. In the wider community of Lower Shader, Upper Shader and Ballantrushal respectively, three men were especially recognised for acts of bravery, Alan Morrison DSM, Alexander Macdonald DSM and Angus Macleay the George Medal. Of the Lower Shader total of servicemen, 38 men served in the RNR. One of those was Alexander Mackay who was assigned to the armed merchant cruiser F94 Salopian.

HMSSalopian, formerly the 10,000-ton Bibby Line passenger motor ship Shropshire, had been hastily requisitioned and renamed by the Admiralty at the outbreak of hostilities and, like over 50 other similar vessels, converted to serve as a ship of war. A major function of such vessels was to act as escorts to protect convoys. What was remarkable about Salopian after conversion at Birkenhead was that, of her 200 plus complement, 41 were from the Isle of Lewis.

In October 1939, Salopian sailed north on her first deployment. As she passed through the Minch, Alexander and his Lewis shipmates could witness the tantalising sight of Loch’s villagers busy with the harvest. But there was no stopping and soon they joined the great Home Fleet at Scapa Flow. They had not been long there when the German U-boat, U-47, under the command of Korvettenkapitän Günther Prien managed to penetrate the ‘impregnable’ defences and put four torpedoes into the battleship Royal Oak, sinking her with the loss of 850 lives – an ominous indicator of the perils that lay ahead for Salopian and her men. The fleet was immediately ordered to sea and Salopian took up patrol duties in the Denmark Strait.

By all accounts, notwithstanding the dangers and the harsh weather conditions, Salopian was a happy ship. With several bards on board, the rich banter and hilarity can be imagined, as described in the song ‘Oran a’ Chrùsair’, composed by Alexander’s shipmates John Mackay and Calum Maclennan. By virtue of Salopian being a former passenger liner, conditions on board were well above the norm for a warship. No hammocks here, but two berth cabins for the men and single first-class staterooms for the officers.

After her initial winter duties in Arctic waters, Salopian went south to West Africa and then Bermuda where thick ganseys and duffle coats were exchanged for tropical whites. It was not long, however, before she was transferred back in northern waters to join the Halifax Escort Force to support the transatlantic convoys. These duties involved escorting each convoy from Canada to the western edge of the U-boat danger zone where it would be handed over to a British destroyer escort. On 12 May 1941, after such a handover of convoy SC30, Salopian, under the command of Captain Sir John Meynell Alleyne, DSO, DSC, RN, turned at 3.30am to head back to Halifax.

Twelve days earlier, on 1 May, unknown to Salopian’s happy crew, the German submarine U-98 sailed from Saint-Nazaire for operations in the North Atlantic under the command of Kapitänleutnant Robert Karl Friedrich Gysae.

Gysae’s log describes how at 4.00am on 13 May, a shadow was identified at 30º on his port bow. The shadow became larger, taking the form of a large passenger liner with no running lights steaming fast and making strong zigzags. It took until 5.30am to get into a position to fire a double salvo of torpedoes which missed because the enemy changed course at 90º. The U-boat had to move fast on the surface to get another opportunity to fire which she did at 6.22am. These two torpedoes also missed their target which steamed away in the dawning light, undamaged as a mist descended. Gysae kept to his course, reloading the tubes as he proceeded, and suddenly at 7.20am the lookout spotted the steamer through the mist on the port bow. Five minutes later, two torpedoes were fired in succession and this time they found their target. The first hit amidships and the second detonated under the bows. The ship stopped, listing slightly to starboard, but showed no sign of sinking. Gysaes noted men scurrying on deck, boats being readied and guns manned. Just as the hatch was sealed for diving, two impacts from the ship’s shellfire were felt with splinters clattering against the hull. U-98 dived to safety.

On board Salopian, Gysae’s first four torpedoes had been unnoticed and it was only during the third attack that a suspicious object was sighted on the starboard beam. Action Stations were sounded and the helm put hard aport, but too late. Both torpedoes struck, the first bringing down the wireless aerials and putting the engines out of action. Allayne ordered all his men into lifeboats except key officers, damage control parties and gun crews. While a large war ensign was raised defiantly on the foremast, all hands worked with quiet efficiency and the advance party got their boats away in good order.

The U-boat surfaced and Salopian’s six-inch guns opened fire, causing the German to submerge. It was only a matter of time before he would strike again. The order was given for final abandonment. The next torpedo hit the ship aft which caused the ship to heel slightly making the lowering of the last two boats easier. During the whole abandonment process, several men were able to get to their quarters to retrieve personal items. Time was also taken to load petrol for the motor boat. Once all the boats were away, another torpedo struck, but still she floated. And then the coup de grâce broke her back. Both halves stood on end and disappeared in less than a minute.

To the credit of the U-boat’s commander, he left the occupants of the boats unmolested. Robert Gysae in command of U-98 sank ten Allied merchantmen between October 1940 and February 1942 when he handed over command to Oberleutnant ZS Kurt Eichmann under whose first deployment U-98 was lost with all hands. Gysae survived the war serving in the post-war Bundesmarine in which he reached the rank of Flottillenadmiral. He died in 1989.

On the motor boat’s emergency wireless a signal was transmitted ‘AMC torpedoed 56º43N 38º57W’. For the rest of that day they waited. When the boats clustered for the night, a roll was called and it was discovered that they had lost three men – engineer, fireman and bosun’s mate. The following day, 14 May, the boats stretched out on a north south line to make it easier for searchers to find them. The men were rationed to half a biscuit, an inch cube of corned beef and two half-measures of the water dipper per day. The ship’s doctor checked the condition of the survivors and on examining Alexander, he declared that if the privations continued, he (Alexander) would be the last man alive on account of his strong and heavy build. These comments were not wholly welcome, for the looks and hostile comments of the other men displayed little empathy with the doctor’s prognosis.

Next morning, the motor boat was dispatched to steer south as far as fuel would permit, in the hope of intercepting a convoy that they knew was on its way. Thankfully they made contact with a destroyer, HMSImpulsive, which picked them up and then rescued the others. Impulsive, running low on fuel, headed for the nearest landfall at Reykjavík in Iceland where Salopian’s commander and 277 officers and ratings were disembarked.

Alexander Mackay and his shipmates, including another 40 Lewismen, were taken to an army camp at Hafnarfjörður some seven miles from Reykjavík, where they were clothed, fed and found welcome sleep. On 26 May, the Salopian survivors boarded the Royal Ulsterman, departing early the next morning for Gourock. In peace time, the Royal Ulsterman and her consort, Royal Scotsman, were the nightly mail ships on the Glasgow-Belfast run. It is an interesting coincidence that the Royal Ulsterman was the first ship on which I sailed as a toddler to visit relations in Northern Ireland.

Alexander Mackay was fortunate to have survived the U-boat menace and there was joy in that a further son Kenny was born in 1942. The family was not, however, without its share of personal grief. John’s mother Mary had suffered the death of two brothers, who were lost aged 21 and 29 years in the space of five weeks between October and November 1944. Both served in the RNR. As we shall see, this was the beginning of a series of heartbreaks due to loss of young lives which were to plague the family in years to come, and which could not but have had emotional consequences for family members.

On the cessation of hostilities, Alexander Mackay returned home to Mary and his young family to resume weaving. They were blessed with a fourth son, Donald John, in 1946 and, on 24 June 1948, their fifth son John Angus, the leading character in our story, was born. In 1953, the last of the Mackay siblings was born, Annie Henrietta or Annette, the only girl in the family.

The Young John Angus

IN HIS EARLY years, John Angus Mackay was unlucky with his health, and seemed also to have a propensity to land himself in the wrong place at the wrong time – a marked contrast to the serendipity he demonstrated in his later professional life, learning from his own, and others’ experience. From birth, John Angus was very short-sighted. Later his mother told him that she had suspected from early on that her fifth son could not see very well. She would wave a teddy or some toy above his head and his eyes never moved, whereas if she did something with a toy that made a sound he could hear and follow it. To add to this sensory impairment, in the course of an epidemic, John contracted measles and mumps around the age of two. This caused a burst eardrum so that his hearing was henceforth seriously impaired.

Worse was to come. As was usual at that time, the house had an open fire on which his mother cooked. He was about three when his brother found a pipe, which was an occasion for excitement among the bigger boys. Angus sat on the chair by the fire pretending to smoke the pipe, which of course led to much hilarity. As John jumped up to try to grab the pipe, Angus pushed him off such that he fell right back into the fire and overturned a boiling kettle This scalded him very badly on and under the shoulder, to the extent that he nearly lost his arm. That was bad enough and extremely painful but the wound started to go septic with proud flesh exposed. The treatment at that time was harsh. The nurse came every day with a pumice stone to scrape proud flesh off the raw wound.

On the nurse’s arrival, John would try to hide in terror in the barn behind the Jersey cow, covering himself in straw. His brother always found him and pulled him out as he screamed ‘a’ chlach ghorm! a’ chlach ghorm! (the blue stone, the blue stone!)’

Poor eyesight and hearing, plus this accident and later experiences left him sub-consciously wary and frightful of close relationships, even although needy of them, in case he was hurt or caused hurt. Recognising this later in life was a cathartic experience, albeit tinged with regrets.

In some ways, the young John was relatively unaware of his handicaps. His earliest indoor memory was the still incomplete house in which he slept in a box bed under the stair and from which he could hear the Gaelic conversations of the adults – a haven of physical and emotional safety. Of course, at that time, Shader was a wholly Gaelic-speaking community.

Outside the house, the memory of horses and carts passing to collect peats was to be a lasting one. What to him were gigantic animals pulling carts with very big strong men on the carts made a powerful visual impression on one whose sight was poor.

In 1955, the family was plunged into grief when the nine-year-old Donald John died under anaesthetic in Woodend hospital in Aberdeen. His mother never fully recovered from this, coming after the loss of two of her brothers in the Second World War some eleven years previously, and consequently this affected her youngest son deeply. Island communities at this time were struggling to build lives after the ravages of two wars in which heavy losses had been inflicted with hardly a family untouched. Family deaths were the subject of outpourings of grief which were terrifying to young children.

The next accident occurred when John was about nine. The milk lorry came to the school every day to deliver the milk and, on the way back, stopped to collect the empties. Somebody thought of the bright idea of hanging on to the back of the lorry and then to let go. All the boys got engaged with this until one day John’s cousin suggested that there should be a competition to see who could stay on longest. John was determined to make his mark so he grabbed the back of the lorry. The others dropped of one by one, but John still hung on. The lorry started to pick up speed, however, and he realised that after a while he had to pass the post office where there were always people standing outside yacking. He then had the picture in his mind’s eye of people standing there. They would all wave at the driver and then say, ‘Goodness gracious’ (or Gaelic expletives to that effect), ‘there’s someone hanging on to the back of the lorry.’ What consternation that would create! To avoid the impending embarrassment, John let go and hit the road hard, probably bouncing in the process. Head and knees were the young john angus hurt, but no lasting damage except for a life-long scar on his forehead. It is with some irony that John Angus states that there are not many people who can claim that they fell off the back of a lorry. This incident showed he had a propensity to hang on in there when others let go – even to the detriment of his health. He was to demonstrate this same characteristic in adult life.

In later years, John Angus recalled that the happiest times in his childhood were usually in the company of adults and animals. Among his own age group there was quite a lot of rough and tumble. The older boys stirred things up and encouraged fighting each other or lining up in teams to emulate Rangers and Celtic. When not doing that, fights took place with the boys from the neighbouring village of Borve, which involved chasing each other with clods and stones until the Shader gang escaped over their home boundary.

From an early age, John had the benefit of the experience of growing up and participating in a working crofting community where the pattern of the year was dictated by the seasons. In the spring, manuring the fields, ploughing and planting, lambing and calving; followed by the peat-cutting and gathering and sheep gathering and shearing in the summer; hay and oats scything and stacking, potato digging and storing in the autumn; and in the early winter, sheep going to the tup and subsequent daily feeding of sheep and cattle.

Most of this work was done by hand with tools which are common to rural communities throughout Europe. Initially ploughing was by horse, though by his mid-teens John’s father had purchased a Massey Ferguson tractor and implements which made life easier. For years, his brothers being at sea, John had to draw household drinking water from a well about quarter of a mile from his home and, until the advent of electricity in the ’50s, lighting was by Tilley lamp or lantern. From resenting the drudgery of having to do what was demanded, John grew to love crofting life and gradually took on responsibilities on his own initiative.

As for school, John hated it. This is understandable when, like the other crofter’s children, he went in to Airidhantuim Primary School not speaking any English, other than his mother’s coaching on how to ask to go to the toilet. From the day of entry into that system of cultural annihilation, English was all these five-year-old Gaelic-speaking pupils heard until they returned to their families in the evening. With hindsight, it seems astonishing that this deliberate official policy of undermining Gaelic, and the rich culture it carried, was accepted with little demur from those on which it was inflicted.

One small but important official crumb that was on offer to the Gaelic community was the radio. John remembers people being practically glued to the receiver to listen to what little Gaelic was then broadcast on it.

At school, due to a lack of confidence due to poor eyesight and hearing, John instinctively sat unobtrusively at the back of the class until it was discovered that he was struggling with the work. He was thereafter moved to the front and was prescribed glasses. From that time, John has had the strong belief that, when a person has weaknesses or deficiencies, they either go down or fight against them. What seems to have grabbed John was a survival instinct that urged: ‘Don’t let this get you down’. Out of that instinct, a spirit of rebellion seemed to have emerged rather than a desire to achieve or to be something. Now that he had glasses, John could read; and he read books avidly – books, it has to be said, that were well above his level. This strength became an antidote to the bullying, which took advantage of his weaknesses.

Although the communities of rural Lewis were immersed in a rich corpus of Gaelic song, verse and lore, this was ignored almost totally by the Anglo-centric school curriculum. As an example, even the music lesson, provided by a peripatetic music teacher, could hardly at times have been more alien and inappropriate to young children who were supposed to be learning English.

De Camptown ladies sing dis song

Doo-da, Doo-da

De Camptown racetrack’s five miles long

Oh, de doo-da day.

Gwine to run all night

Gwine to run all day

I bet my money on de bob-tailed nag

Somebody bet on de bay.

Thus they were exposed to verse that was not only incomprehensible and lacking in relevance but exhibiting a similar type of racist ridicule to which the Gaelic community itself was being subjected.

One song that John recalls that did have a Scottish connection was ‘Will ye no come back again?’ But again, although of some cultural relevance, there was little explanation as to who ‘Bonny Cherlie’ was, or why he had gone away in the first place. And why that song, when there are a hundred well-known Gaelic songs about the campaign of 1745– 6 and its aftermath? In fact, throughout the primary school experience, there was next to no Gaelic until Primary 6 or 7 when the headmaster would read some Gaelic from a book and then ask each pupil to read a section.

For all these deficiencies in the primary education system and for all his own handicaps, the eleven-year-old John Angus Mackay survived scrapes and scraps, while his own reading, coupled with his growing experience of agriculture and community life, had given him a breadth of learning that was unusual.

In those days at the end of the primary stage of education, all Scottish children sat an exam which would determine whether their secondary education would be in an academic or non-academic institution. This exam was known as the Eleven Plus. When John sat the Eleven Plus, he got exceptionally high marks; on the strength of which he was bound for the Nicolson Institute in the island capital of Stornoway. His brother Angus had also attended the Nicolson, but due to chronic asthma, had missed many of his classes and left at the age of 15 to become a sailor. Ultimately, when John was in his mid-teens, Angus emigrated to New Zealand, where the climate suited his health better.

Cabadaich 1: Nuair a Bha Mi Òg

Blethers 1: When I was Young

ROY: Rural Lewis in your youth was very different from today. Remind me of some or the characters.

JOHN: I lived in the village of Shader where work revolved around the land, animals – cattle, sheep, horses – and the seasons dictated how people lived. When I was very young, we had no mains water or electricity – the tobar (well) and the Tilley lamp were the order of the day. When I looked out from our house, I could see people working on their crofts. I could see peat smoke rising from the chimneys. From this you could tell that people were alright. Life revolved around the land and the simple equipment that we used. Most crofters were also weavers of Harris Tweed. And, of course, Gaelic was the language of the community.

One of my earliest memories is watching a competition between my aunties – my father’s sisters – and my father. It was just on the cusp of when we were changing from sickle to the scythe. My father, however, used the scythe. The aunts who used the traditional sickle said, in Gaelic of course, ‘This will never work. It’ll make a mess of the corn.’ So there was a competition. The two aunties were bent double cutting away with the sickles, while my father walked swinging the scythe – swish, swish. My father won! That was my first experience of tradition versus modernity. Then my father used the horse for ploughing until within ten years the tractor arrived. Of course, people were saying the same thing: ‘The tractor will ruin the land.’ The tractor then was the small Ferguson.

ROY: You don’t see many horses about crofts today. How prevalent were they in your young day?

JOHN: When I was very young, there were a lot of horses used for cultivation. In the winter, they wandered freely around the village. I well remember a white mare, I used to be lifted on to its back. It was quite docile and it belonged to a guy called Dolly Tee. Now Dolly Tee was famous in the village because, during the First Word War, he saved the life of his brother by attacking sailors with a marlin spike who were about to throw his wounded brother overboard.