Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

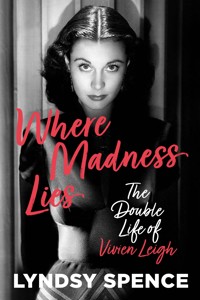

Vivien Leigh was one of the greatest film and theatrical stars of the twentieth century. Her Oscar-winning performances in Gone with the Wind and A Streetcar Named Desire have cemented her status as an icon of classic Hollywood. Her meteoric rise to fame launched her into the gaze of fellow rising star Laurence Olivier. A tempestuous relationship ensued that would last for twenty years and captured the imagination of people around the world. Behind the scenes, however, Leigh's personal life was marred by bipolar disorder, which remained undiagnosed until 1953. Largely misunderstood and subjected to barbaric mistreatment at the hands of her doctors, she also suffered the heartbreak of Olivier's infidelity. Contributing to her image as a tragic heroine, she died at the age of 53. Where Madness Lies begins in 1953, when Leigh suffered a nervous breakdown and was institutionalised. The woeful story unfolds as she tries to rebuild her life, salvage her career and save her marriage. Featuring a wealth of unpublished material, including private correspondence, bestselling author Lyndsy Spence reveals the woman behind the legendary image: a woman who remained strong in the face of adversity

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Lyndsy Spence, 2024

The right of Lyndsy Spence to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 432 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For Louis, with love

‘Yes, there is something uncanny, demonic and fascinating in her’

– Anna Karenina, Leo Tolstoy

Contents

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Where Madness Lies

Afterword

Filmography

Further Reading

Notes

Index

Author’s Note

Ever since I was a young girl, I have been fascinated by Vivien Leigh (born Vivian Mary Hartley) and was delighted to discover her on the Irish side of my family tree, albeit a very distant connection through an Irish great-grandfather whose family, the Robinsons, came from western Ireland. I am positive the fascination sprang from something familiar, or perhaps I was like every other mortal and spellbound from that first glimpse of her as Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind.

Given the themes in Where Madness Lies and the sensitive subject matter of mental illness, it would be easy to cast Vivien as a tragedienne. I do not see her as a victim; however, I think it is important to look at her life within the period she lived, particularly when it came to women’s health and understanding the complexities of the female mind. Attitudes to mental health were draconian, to say the least, and the medical treatment she received left a lasting impact on her. From my own perspective, I see Vivien as a complex woman and the ongoing narrative surrounding her is filled with grey areas, which, to me, makes her all the more interesting. She was a headstrong woman who trusted her instincts, for better or worse, and stood by her convictions. I find that admirable: where there is truth, there is integrity, even if her behaviour was far from noble.

As with all my subjects, I am always intrigued by the woman behind the myth, as opposed to the mythical image which has been cultivated, thanks, mostly, to her film legacy. Everyone knows Vivien as Scarlett O’Hara and Blanche DuBois, and numerous books and articles have been written about her famous stage and screen personas. With that being said, Vivien only made a handful of feature films and managed to win two Academy Awards: the first for Gone with the Wind (1939) and the second for A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) – an astonishing achievement, even by today’s standards. In terms of her career, her first love was the theatre but, to a larger extent, she was celebrated for her marriage to Sir Laurence Olivier, known as ‘Larry’ to Vivien and those close to him. Again, her singular identity was split in half but she was proud to be his wife and then, later, to use the courtesy title of Lady Olivier, even after their divorce in 1960.

Vivien Leigh’s professional life changed in 1939, after she played Scarlett O’Hara, but her private life (and her latter career) was completely altered after her nervous breakdown and the diagnosis of ‘manic depression’ (now known as bipolar disorder). Therefore, I open my book in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) in 1953, the scene of Vivien’s affair with Peter Finch during the filming of Elephant Walk and her mental breakdown, which has allowed me to manipulate the time frame of this book while adhering to facts. It moves forward from 1953 until her untimely death in 1967 more or less in chronological order with triggers to her past. In scenes where Vivien is losing her grip on herself, I took inspiration from photographs and details from her letters to convey those times when her reality was skewed and she felt genuinely afraid of being suspended in a dream world.

The aforementioned has also been done to emphasise Vivien’s struggles after her first course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which Larry felt had erased the best parts of her. The contemporary scenes, which go back in time, allow Vivien, our protagonist, to discover herself and what led her to mental collapse and the subsequent breakdown of her celebrated marriage to Larry. Also, in Chapter 12, the penultimate chapter, there is a sense of displacement after she suffers another breakdown and attempts to, once more, rebuild her life. I wanted the narrative to reflect her ongoing strength in the face of adversity.

The Afterword, ‘A Reimagining’, was inspired by real sessions with a psychic medium. I was surprised to learn of Vivien’s friendship with Sybil Leek, a famous trance medium and a self-confessed witch whose occupations consisted of an antique dealer, astrologer, herbalist, author, and, of course, communicating with the dead. Sybil is an intriguing subject and someone whose life I am interested in exploring further. For the time being, in the Afterword, Sybil’s channelled messages from Vivien’s spirit allowed me to also write of Vivien’s unrealised dream of buying the abandoned villa of St John of the Pigeons, south of Benitses in Corfu, and retiring there to paint when she was 60. It was an ambition cut short by her untimely death in 1967.

I have purposely avoided writing about Vivien’s and Larry’s respective descendants who are still alive and living as private people. I have, where possible, avoided speculating about Larry’s private life with Dame Joan Plowright, who has remained incredibly sympathetic towards Vivien even when she did not necessarily warrant such kindness.

Likewise, in the past, many disparaging things have been written about Vivien’s mental illness and the effects it had on her personality and judgement. I have not censored the uglier side of her illness and how it altered her personality and destroyed most of the things she held dear. But, at the same time, I wanted to give Vivien her power back. The common theme throughout the book is Vivien’s quest to find her way back home, even if ‘home’ is a place of peace and acceptance within herself.

It has been a great privilege to write about Vivien Leigh, who is one of my heroines, and I hope my admiration for her talent and courage is conveyed in this book. As a nod to Vivien herself, her life is told in thirteen (large) chapters, as thirteen is a powerful symbol of femininity and I felt the mysticism fitted her perfectly. As she was a woman of the theatre, I wanted to give my book a theatrical air with symbolism and subtext.

A note on the title, Where Madness Lies: I was drawn to the ambiguity of the title, especially the term ‘madness’ and its play on ‘O, that way madness lies’ from William Shakespeare’s King Lear. It is in no way meant to be a damaging term for Vivien’s mental illness. The subtitle, The Double Life of Vivien Leigh, referring to her double life, was drawn from a magazine headline, circa 1953, which exposed her breakdown in Hollywood. For me, the ‘double life’, as such, was a reflection of her two selves: Vivien, whom everyone loved, and the mental illness which warped her perception of herself and how others saw her. It was the fiercest battle she ever fought and for which I have nothing but admiration.

Lyndsy Spence

County Antrim

Acknowledgements

During my research and the writing of this book, I was aware of the biographies of Vivien Leigh which have come before mine, each one a unique telling of her life through different variations. As a biographer, my goal is to offer a new perspective on whomever I write about and with Vivien, I wanted to tell her story in a way that I felt was authentic to her. I hope it adds to the ongoing narrative about her life.

A note on sources: Vivien Leigh’s letters have been published in past biographies, most significantly in books by Anne Edwards (1973), Alexander Walker (1987) and Hugo Vickers (1988) – I consider those first biographies as groundbreaking regarding the information they disclosed. Laurence Olivier’s personal papers were published in 2005 in an authorised biography by Terry Coleman and in Philip Ziegler’s book, published in 2013.

Vivien Leigh’s personal papers are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A Theatre and Performance Collections) and Laurence Olivier’s papers are with the British Library Manuscript Collections. Vivien’s letters to Olivier are also in his archives at the British Library. There are further substantial archives relating to Vivien Leigh held at the New York Public Library and the Charles E. Young Research Library UCLA. Please see Notes for detailed information on sources.

I am eternally grateful to several people: firstly, my family for supporting my work; the Vivien Leigh fanbase who encouraged my work; and the collectors who have kindly shared their collections online. I am thankful to Kendra Bean, author of Vivien Leigh: An Intimate Portrait and founder of vivandlarry.com; Andy Batt; the Vivien Leigh Circle; David Barry, author of The Final Curtain; Rachel Nicholson; Michelle Beck; Ana Claudia Paixao; Dean Rhys Jones; Nuri Lidar; Andrew Budgell; Eric Sanniez; the late Julia Lockwood; Molly Haigh at Charles E. Young Research Library UCLA; Alexander Turnbull Library/National Library of New Zealand; the State Library of Queensland; Dale Stinchcomb, Associate Curator of the Harvard Theatre Collection; and Greta Ritchie for her kind permission to use photographs from her collection. Thank you to Mark Beynon for encouraging me to write this book and to everyone at The History Press whose support is incomparable.

Lastly, I wanted to reserve my final token of thanks for Shiroma Perera-Nathan, author of God and the Angel: Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier’s Tour de Force of Australia and New Zealand for our discussions on Vivien Leigh, her permission to use photographs from her collection and believing in my hare-brained ideas before they came to fruition.

Chapter One

‘O, that way madness lies’

King Lear, William Shakespeare

1953

‘Oh, the bliss of not having to go mad, commit suicide, or contemplate murder,’1 Vivien Leigh told the waiting reporters as she stepped off the aeroplane and on to the airfield in Colombo, Ceylon. They came to interview her about Elephant Walk, her new picture for Paramount, to be shot on location there. She was exhausted after the long flight by way of London, Rome, Beirut, Bahrain and Bombay. Her leading man, Peter Finch, took her by the arm and escorted her through the sea of reporters and curious faces who hoped to catch a glimpse of the star. The humidity was suffocating and the heat swept over her like a furnace. She stopped to catch her breath, before adding, ‘My character is … a normal healthy girl.’2

On the journey to the bungalows – where the cast and crew were to live for a month – the scenery, familiar from her childhood in the east, filtered through the taxi window. The palm trees, colonial buildings and British cars filled the streets, but an air of unrest stirred beneath the surface during those final days of the empire. Perhaps she thought of her mother, Gertrude Hartley, unhappy in her marriage and heavily pregnant, gazing at the Kanchenjunga – the Five Treasures of the Great Snows – from her window at Shannon Lodge, praying to the saints for her child to be beautiful. Born in Darjeeling on Guy Fawkes Day in 1913, little Vivian – it was spelt with an ‘a’ and not an ‘e’ back then – always thought the fireworks were for her. In those days, her mother’s lies were harmless: ‘Remember, remember, the fifth of November’, Gertrude might have said, as a kaleidoscope of colours exploded above her.

In the back of the taxi, Vivien crossed herself and said a prayer to St Thérèse of Lisieux,3 the patron saint of missions. Although her fellow Catholics considered her a sinner – she left her first husband, Leigh Holman, to run away with Laurence Olivier – she liked the saints and was drawn to mystical things and religious iconography. A trio of crystals – carnelian, citrine and clear quartz – were kept on her dressing table and she carried a carnelian agate in her handbag. The combination of those crystals was, and is, generally believed to attract abundance. But an abundance of what? As for spirituality, she called herself a ‘Zen–Buddhist–Catholic’4 and favoured churches with beautiful architecture and stained-glass windows.5 Her first real experience of the theatre was attending Mass at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Roehampton in London, which was later bombed by the Luftwaffe during the Blitz.

‘All that Catholic mumbo jumbo,’6 Peter said of organised religion. His voice sounded exactly like her husband, Sir Laurence Olivier’s. Larry was his idol – he had been knighted in 1947 for his contributions to the stage and screen – and for Peter, there was no greater actor.

‘No problem, then. Opt out and be a good Protestant,’7 she said.

The Comet carrying them to Colombo would crash two flights later. So, to her mind, the prayer to St Thérèse had worked.

The seclusion of the set unnerved Vivien and everything felt static as she took in her surroundings: the flower-scented air, the sprawling tea fields and the hills in the distance, and the scrutinising glares from the locals, some of whom did not want the production there.

‘The Devil Dancers,’ Vivien’s stand-in, an Australian woman named Carrol Hayward said, as she crept up behind her. ‘The wild folk of Ceylon.’8

‘Sinhalese rituals,’ Peter corrected Hayward. As a boy, he had followed his mother to a theosophical community near Madras. Despite his drinking and womanising in adulthood, and the pain it caused others, he identified as a Buddhist. He detested Christianity and the symbol of the crucifix, saying, ‘I think a man dying on a cross is a ghastly symbol for a religion.’9

It had taken a mere few days for Vivien to lose interest in the picture and she had trouble memorising her lines. It belonged to the adventure genre but felt like a horror story when she analysed the undertones of the script. Her fictional home, a mansion in the jungle called Elephant Walk, was named after the trek of the elephants who marched past it and was haunted by the Governor, her character’s late father-in-law. She was cast as Ruth, the unhappy wife of a tea planter, John Wiley, an unsympathetic character who preferred to drink with his cronies than tend to her. Close-ups were shot of Vivien looming on the staircase, serpent-eyed and commanding him to come to bed. As the plot unfolds, she ends up falling for a fellow planter, Dick Carver – played by Dana Andrews, who was often drunk in real life, but was harmless – and contemplates eloping with him. After typhoid fever breaks out, she remains at the house, which is ransacked by elephants, thus concluding the story.

The truth was, Vivien knew the script was beneath her and not very good, despite being a Hollywood production with a big studio budget. Larry had declined the part of Wiley and dismissed the script as a pale imitation of Rebecca. A little dig, for she had wanted to appear with him in the film adaptation of Rebecca in 1940 but David O. Selznick, the producer, considered her too beautiful for the mousy Mrs de Winter and the part went to Joan Fontaine. In a way, Larry’s rejection of Elephant Walk was serendipitous, or so he thought at the time, and it allowed Peter an opportunity to star opposite Vivien. She had planned the entire thing.

Peter was the first to crack and, after a long day of filming, he hated to be alone at night. Vivien, an insomniac all her life, was glad of the company. They spent their nights in her bungalow, sitting at the sugarcane table, playing Canasta, chain-smoking and drinking too much gin. All Peter wanted to do was talk about Larry, and Vivien was tired of him fishing for compliments and looking to be reassured of his talent. At almost 40 and yet to have his big break, he said he was grateful for anything he could get.

‘But you don’t take what you can get. You let people persuade you as to what they think is best for you and throw dust in your eyes,’ she said, exasperated. ‘You’re a good enough actor to stand alone as someone quite different and still do what you really want as an actor, but you have no follow-through. You play at life, play with women, and you dissipate your God-given talents because you don’t believe in your own wonderful star.’10 There was sincerity in her words: she had believed in Peter’s talent from the first moment she saw him in The Imaginary Invalid at O’Brien’s Glass Factory in Sydney in 1948. Both she and Larry felt he was unstoppable.

As a child, Peter had been sent to Australia to live with his great-uncle, as his mother, Alicia Fisher, known as Betty, was incapable of looking after him. Betty was too busy with her love affairs, which had disastrous consequences for Peter, both in his childhood and adulthood. The man whom he thought was his father, George Finch, was not, and his mother’s second husband, Jock Campbell, an Indian Army officer, was, in fact, his biological father.

Vivien did not try to console him, they were both too intoxicated. She had abandoned her only child to run away with Larry, who, in turn, left his child, a boy named Tarquin. Vivien’s mother had abandoned her, too – sort of. She had been sent from India to Roehampton at the age of 6 and put into a convent school: she was pupil no. 90, Vivian Mary Hartley.

After Peter returned to his bungalow, Vivien stayed up drinking. She had the odd feeling of being fixated on something. On what? She could not decide; everything inside her brain was that of white noise, desperately searching for a connection and failing.

The following morning, she sent Larry several telegrams, begging him to come to Ceylon for a week. As her mental stability declined, her writing became worse and she dashed off erratic postcards to people.11 Only later would it become known as a symptom of her condition, manic depression, then undiagnosed. There was no answer and she suspected the crew were intercepting her mail in order to manipulate her into doing their bidding. Larry’s picture, The Beggar’s Opera, was in post-production and he went to Ischia to stay with friends. Those details escaped Vivien. In her diary, she wrote his name several times, underlining it each time, as though she were performing a ritual to summon him.

Outside in the fields, she imagined Larry was coming towards her, his shirt sleeves rolled up and his body bronzed from the sun. ‘Larry,’ she called to Peter, who tried to correct her. She ignored Peter as she walked into the water. His instincts told him to follow her. She swam out as far as she could go, weighed down by her flimsy dress, and floated on her back, staring at the blistering sun creating prisms. Or was it a dream? She heard bells, the way Blanche DuBois also heard bells at the end of A Streetcar Named Desire. The bells from the temple purified the air, reminiscent of the Sacred Heart’s daily toll for Mass: The precious blood of our Jesus Christ, wash away our sins.

Later that day, Vivien returned to her bungalow and opened her diary, scribbling, ‘Please come!!!’ under Larry’s name, and then she started to sob. There was a knock on the door and she opened it, without concealing her tears. Her makeup was streaked down her cheeks. It was Peter and Dana Andrews, the latter puzzled by her sadness. They invited her on an excursion into a nearby village and she agreed to go without saying a word. She closed the door and hooked on to Peter’s arm.

In the village, the locals gave the trio quizzical looks and Vivien’s spirits were lifted by the bazaar and its stalls of colourful saris, sweets, silver and gold paper, and imitation antique knives and swords covered in rust to look more valuable to gullible tourists. The aroma of spices coming from the dekshis filled the air, suffocating the senses in the heat and humidity. A snake charmer caught her eye. ‘Oh look, isn’t he a pet,’12 she said as a baby cobra slithered out of its basket and swayed to the music of the flute.

The charmer invited her to sit on his stool and he coiled the snake around her neck while she roared with childish laughter and a cigarette burnt between her fingers. She stared into his black eyes, her laughter stopping. The lilting music drew larger cobras from the baskets and they danced in unison. Astrologically speaking – as she did believe – it was the year of the water snake. They, the snakes, were not to be trusted; they only cared about their own agenda.

Once, she had read a book called The Martyrdom of Man and underlined a passage that resonated with her: ‘And the artists shall inherit the earth and the world will be as a garden.’13

The Garden of Eden.

The Garden of Evil.

The production moved to Kandy, a city situated at the foot of a circle of mountains, for three days to shoot among the ruins of the old kingdom. Vivien became impossible to work with and made a scene when the dresser tried to put her in shorts. ‘My legs are not designed for shorts!’14 she said and refused to film unless they were discarded. Her hands, legs and feet were her biggest insecurities and she felt they were too large for her petite frame.

As a star, Vivien had autonomy over her body, something that was not the case in 1939 when she filmed Gone with the Wind. Its producer, David O. Selznick, was fixated with, what he called, the ‘chest experiment’15 and he ordered Walter Plunkett, the costume designer, to use adhesive tape and padding to create the illusion of cleavage from her (Selznick’s description) flat chest. So, Vivien suffered the indignity of standing naked from the waist up, while Plunkett and his assistant applied the tape, all the while she complained it cut off her circulation and she could not breathe. High on Benzedrine, which Selznick ate like popcorn,16 he admired the results of her period costumes which no longer caved in at the bust.

On the set of Elephant Walk, all her fears came to light. One day, a young Sinhalese man came to the makeup department to ask if she was ready to go to the set. She began trembling and remained shaken, even after he left.

‘What’s the matter?’ the makeup man asked her.

‘I’m sorry. I’m … I’m so frightened of black eyes. I’ve always been frightened of black eyes,’ she replied.

‘But my eyes are black and you’re not frightened of me,’ the makeup man said.

‘No. Your eyes are not black. They’re dark brown. I mean black – Indian black.’17

The producer, Irving Asher, came and tried to reason with Vivien but to no avail. Asher escorted her to her chair, where she continued to tremble. The stand-in, Carrol Hayward, and her husband, who was standing in for Peter, hovered close by, watching and whispering. Vivien hated them, especially Hayward, whom she rightly sensed was conspiring against her, even if everyone else thought it was paranoia.

‘Lady Olivier,’ Hayward slipped up behind her.

‘Honey,’ Vivien said, in a Mississippi drawl reminiscent of Blanche DuBois, ‘in the profession, I am just Vivien Leigh.’18

The long day of filming in the blazing sun was pointless, as they only managed to capture long shots of Vivien while the rest of the cast had to interact with her stand-in. Having felt listless all day, at two o’clock in the morning, she decided she wanted to throw a party, and banged on the doors of the cast and crew. The ones who answered her call declined.

‘Oh stick-in-the-mud,’19 Vivien said, uncaring of their hostility towards her.

The night was spent writing more letters to Larry, sending bizarre orders for him to pack her evening dresses and bring them to her in Ceylon. In her diary, she noted her lobster dish, the absence of elephants, and the dancing cobras on the set. She could not sleep: she thought she heard voices and it kept her up all night.

In the morning, she reported to hair and makeup and was told there would be no close-ups taken of her that day. Demanding to know why, Asher told her she looked like hell; her face was bloated from a combination of heavy drinking and sleep deprivation. They took more long shots and managed a few with dialogue, but she stumbled over her lines. ‘She’d spend hours meeting natives,’ Carrol Hayward observed. ‘The strain’s too much for her.’20

‘Natives’ was how Hayward referred to the locals and to the Sinhalese extras, who kept to their segregated area between filming … ‘The wild folk’. She did not hide her disapproval of Vivien associating with them.

Vivien’s mother, Gertrude, was rumoured to have been mixed race, but the terminology in those days was far more blatant: she was called a ‘half-caste’. Then and now, the caste system in India dictated a person’s social rank and the respect they could command; however, nobody in the immediate family delved too much into their ancestry. Vivien knew the truth: Gertrude, with her porcelain skin and grey-blue eyes, favoured her maternal Irish side – the Robinsons from western Ireland; but her paternal side, Yackjee, was Armenian and often mistaken as Parsi. Gertrude’s family was intertwined in the complicated tapestry of British India: her maternal grandparents were killed in the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and her father, Michael Yackjee, who died when she was 5, had worked as a station master for the East Indian Railway Company. One day, Gertrude would marry an English gentleman, but not quite: she married a Yorkshireman born in Scotland whose forebears ran a pub in Pontefract.21

That’s when Gertrude played the part of denying her true self and negotiated the unforgiving caste system. Gertrude pretended to be white and so did Vivien, and they drew on their Celtic heritage at the mere mention of India. As an adult, Vivien would have what she described as her crinkly hair straightened before being set in rollers – a tedious routine but the smooth results were to her liking. ‘I’m not really English,’22 Vivien said as she grew older and embraced the cultural differences around her. She did not identify as English or British or anything in particular, viewing herself as a citizen of the world with no prejudices towards colour, creed, religion, gender or sexuality. People were people, she did not adhere to social rules.

On the day Carrol Hayward had to film the stampede scenes, a dozen real elephants were brought to the set. It took five takes, as Hayward was terrified of the elephants and outran them each time. Vivien watched from afar, as if in a trance. She had touched the elephants, once, and recoiled from their hot flesh.23 Or had she dreamt it?

Hours later, Peter found Vivien sitting in a tea field on the hillside watching the faraway fires from Sinhalese rituals. The locals warned against sitting out in the night air: its dampness would purge any hidden fever or sickness from the body.24

‘You’re an old soul. Larry’s a brand-new soul with a plastic karma and a marital deficit balance,’25 she said, perhaps adopting the supernatural beliefs she was privy to in Ceylon.

‘That crow …’ Peter’s voice was distant, ‘is saying you’re lonely. Are you?’26

She fell into his arms sobbing and calling him Larry,27 pleading with him to sleep with her. In the moment, and in the guise of Larry, he consented to her wishes.

Wracked with guilt, Peter continued the charade of becoming Larry when she needed him most. He recalled the first time he saw Vivien, at O’Brien’s Glass Factory in Sydney, after his performance in The Imaginary Invalid. She intrigued him; there was something so helpless in how she clung to Larry, afraid that, if she let him go, she would be set adrift.

And then, as if by magic, Vivien was told Larry would be coming to Ceylon the following day. The logistics of his journey escaped her and she stayed up all night, anticipating their reunion. She went to Ratmalana airport to greet him and stood on her tiptoes, looking above the travellers’ heads, with nervous anticipation. There she waited, dressed in a thin cotton dress, her hair curling from the humidity, and her nose and cheeks bronzed from the sun. This image of vulnerability did nothing for him and he stunned her by asking why she was not before the camera acting. In front of the travellers passing through the small baggage area, she flew into a blind rage and accused him of plotting against her.

In the car, she suggested stopping at a rest house for a ‘little drink and a little relaxation’.28

His mouth moved but she heard nothing of what he said. To her, he was a mirage. He was beginning to resent the time and money he had spent travelling to Ceylon.

They went to Helga’s Folly, a hotel in Kandy overlooking the jungle and rumoured to be haunted by the ghosts of star-crossed lovers. Peter was waiting in the foyer and he muttered a polite greeting to Larry and vice versa. Vivien slid next to Peter and wrapped her arms around him, all the while she stared at Larry. It became clear to Larry that Peter had replaced him, though he felt no resentment and was relieved someone else was shouldering the burden. If she wanted a violent brawl, she did not get it.

Instead, Vivien and Larry climbed the hill to Karunaratne House, the building designed by Minnette de Silva. They were silent for the first part of their ascent: he was harbouring his own little secret. During the filming of The Beggar’s Opera, in which he played Macheath, he had had an affair with Dorothy Tutin, who was cast as Polly Peachum in the picture. Tutin was 23 and a graduate of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), having completed the course in 1949. If coincidences in timing were anything to go by, he knew, in 1949, that his marriage to Vivien was over but continued to cling to their image instead of the real thing. As they climbed higher, they began to improvise a one-act play of two cockney naval ratings talking crudely. Vivien was gruff and spat over the rails of an imaginary destroyer and was scolded by Larry, her boss.29 Acting was the only way they could communicate, or as Larry said, ‘It’s a great relief to be in someone else’s shoes.’30

When they came back down to earth, they had nothing more to say. Larry spent a full day talking to Irving Asher and observing Vivien. On set, she seemed unaware of his presence and, a day later, he disappeared.

The production left Ceylon for the soundstages of Hollywood. As the aeroplane began its ascent over the Indian Ocean, Vivien unfastened her seatbelt and stood up, screaming that the wing was on fire. She became hysterical and made for the exit, threatening to throw herself out. Then, she tore at her clothes, ripping her dress down the middle, and fought with Peter, who tried to reason with her. The stunned passengers watched, in horror, as she was restrained and forcibly sedated with sleeping pills, which periodically wore off on their journey. Coming to, she began her outbursts all over again and, once more, would be sedated for the next eight hours or so.

Seventy-two hours later, the plane finally touched down in California. On the way to the Beverly Hills Hotel, Vivien decided she wanted to stay with Peter in the house he rented for himself, his wife and their daughter. So, the car was detoured to the Finches’ house in Hanover Drive. At the house, she began to divide her living quarters from Peter’s family.

Peter’s wife, Tamara, and their 3-year-old daughter, Anita, had sailed to New York on the Queen Elizabeth and then flew to Los Angeles. After the long journey, Tamara was faced with Vivien, on a high, dressed in a red and gold sari and looking like Scarlett O’Hara. She demanded that Tamara change into a sari for a party given in her honour and seethed with jealousy when Peter showed his wife affection and praised her appearance – her dark, Romanian looks were compared to that of an Arab stallion.31

Within moments, close to seventy guests descended on the small property and Vivien was nowhere to be found. She was locked in her bedroom, lying across the bed, sobbing and trying to reach Larry on the telephone. Knocking on the door gently, Tamara tried but failed to coax her out. Still, the wretched sobs continued and were heard by the guests downstairs.

Although Tamara never found Vivien easy to be around, she had always admired her. When she met her in Sydney in 1948, she considered her beautiful and vulnerable, and was astounded by her ability to remember everyone’s names and little titbits about their daily lives. It charmed everyone. Tamara, thinking she had made a friend in Vivien, confided that when she first met Peter, at the beach, she was reading Gone with the Wind. It was a sweet story but Vivien remained unmoved; she had first read Gone with the Wind after snapping her ankle on the ski slopes of Kitzbühel. In a way, it would change both of their lives.

In England, when Tamara began socialising with Vivien and Larry, she felt out of place and knew they had wanted Peter’s company and not hers. There was a certain tone that Vivien used when she wished to be imperious – an efficiency which one acquired when ordering servants to do their bidding. In turn, Vivien expected others to show her the slavish devotion that her Ayah (nursemaid) had in India. Tamara, who was also cultured, realised that Vivien’s beauty was not her greatest weapon but her brain. Vivien was a magpie who collected knowledge from others, memorising wine lists, plays, poems, witty anecdotes and foreign languages – French, German, Italian and Spanish – anything to cut others down to size. Nevertheless, Tamara did not recognise the woman, behind the door, who was falling to pieces.

Suddenly, for Tamara, everything fell into place and she realised Vivien had set her sights on Peter. Back in 1948, the first thing Vivien said to Tamara was, ‘You bring that clever husband of yours to England. You must promise.’32

Tamara had delivered on her promise, and then some. But she was not the fool Vivien thought her to be and had known, for some time, that her marriage to Peter was coming to an end. Concerned individuals asked how she could stand such things. ‘Ballet is a cruel business. Very cruel,’33 Tamara said of her art and, perhaps, similarly justified her life with Peter.

Tamara set off to find Peter, when Vivien suddenly appeared at the top of the stairs. She glared in Tamara and Peter’s direction before walking towards them. Something about Tamara’s elegance – she had danced with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo – rattled her. The women had become a threat to each other and Peter was unsure who would be the victor. Both had honed their survival skills in infancy: Vivien, alone in the convents of Europe, and Tamara, a nomadic life after her grandparents were slain by Soviet bayonets.

Vivien, for now, succeeded in wounding Tamara and lost an expensive ring Peter had bought her in Ceylon by discarding it in the airport bathroom.34 It was no accident and she reminded him that Tamara was unaccustomed to displays of wealth, having married him when he was poor. Vivien understood the symbolism: her father was a womaniser and her mother always knew when he had had an affair – mostly with her friends – for he would buy her a trinket.

Later that night, Tamara exerted her superiority and shared Peter’s bed. At two o’clock in the morning, Vivien pushed the door open and tore off the bedclothes, screaming obscenities at both of them. ‘You haven’t told her, you haven’t told her!’ Vivien railed at Peter. ‘How could you be sleeping with her, you monster? You’re my lover!’35

The following morning, Vivien wrung her hands and sobbed like a child, searching for sympathy from Tamara, explaining that her behaviour was not her fault and it was the result of Larry’s coldness towards her. There was sincerity in her voice and Tamara believed her, as she seemed more balanced than before, and they spent the day sunbathing by the pool and eating avocado salad.

Vivien told Tamara they could only converse in French and the two women discussed trivial matters and it was apparent that Tamara, who had lived and worked in Paris, was far more fluent in the language. Distressed, Vivien jumped into the swimming pool and swam laps, which exhausted her and she struggled to stay afloat and breathe. She screamed that she wanted to drown, she wanted to die, as Tamara dragged her to safety.36

In that state, Vivien was unpredictable and violent: she flew at Tamara with a knife and, soon after, cut up all her clothing. She told Anita to shut up and asked for her to be removed from her sight. To appease Vivien and give the child a sense of normality, Anita was placed in a Hollywood preschool.

Things weren’t much better on the set when Vivien recited her dialogue from A Streetcar Named Desire to Dana Andrews, as though he were the character of Mitch. Dana was too drunk to respond and fluffed his own lines to her. When corrected, she broke down sobbing, ‘You’re all telling me what to do. I know what I’ve got to do. I’ve got to get back to work.’37

The studio dismissed Vivien that day and sent her home. Arriving at Peter and Tamara’s house, she found her bags packed and waiting in the hallway. Peter delivered the news: she would have to go. In his own words, he wanted to ‘blot out the bloody business once and for all’.38

Chapter Two

‘We know what we are, but not what we may be’

Hamlet, William Shakespeare

1953

The house in Hanover Drive had its curtains drawn. Vivien hated sunlight and loathed to be seen in full glare; it was her latest fixation and, like all of her phases, it would pass. Just as the character of Blanche DuBois did, she avoided strong light. It was not method acting but, rather, the parts she played revealed layers of her psyche; each character awakening the pieces she had suppressed.

The door was on the latch and Larry pushed it open without much effort. He was jet-lagged, owing to his journey from Ischia to London to board a flight to New York and then a connection to Los Angeles. How many hours had he been travelling? How many days and time zones had he crossed? It was now 11 March, so three, almost four days, in total. Funny, how things worked out: it was on 11 March 1937, some sixteen years earlier, she had begged him to leave his first wife and run away with her. Months later, they had executed their plan and eloped. It was a date not to be forgotten.

Then and now, Larry was an emotional wreck, torn apart by his duty to his wife and passion for his mistress – the latter description was too strong a word. Here he was, a vagabond in smart clothes: unshaven, wearing his crumpled suit, and his shirt sticking to his back. He wandered down the long passageway and up the creaking stairs, the narrowness surrounding him like a secret tunnel. The bedroom door was ajar, voile curtains hung limpid against the arched window, which opened on to a small veranda. Overall, the shabbiness, created by her (and so unlike her), belonged to 632 Elysian Fields, the temporary abode of Blanche DuBois, or, in their world, a set. Before he focused his weary gaze on the bed, he detected her shallow breathing. If they had been following a script, the description might have been as thus: Clothes lay on the floor, over the chair and spilt from the chest of drawers. A lamp had fallen over and pages of the mediocre Elephant Walk script were strewn across the room.

Larry began to speak, his voice suspended in disbelief, thinking she was pretending to be insane. Then it hit him: she had been expecting someone else.

‘Is something the matter?’ he asked.

‘I’m in love,’ she said.

‘Who with, darling?’

‘Peter Finch.’1

All his instincts told him he should have been furious. Had it been five years ago, he might have belted her, hard across the face, as he had done in Australia when she made a scene about having misplaced her red slippers and refused to go on stage as Lady Teazle in The School for Scandal until they were found.

‘Get up on that stage, you little bitch,’ he had said, slapping her.

‘Don’t you dare hit me, you – you bastard,’2 she had retaliated.

But they were too far gone for such passionate displays. He had his own dalliances; they were self-pitying indulgences and a tonic for his sorrows.

Now that the initial surprise of what he might have found had lapsed, he was overcome by the smell of stale cigarettes and gin. She sat up in bed and laughed, a shrill note scoring the manic scene. Or was it the blue piano from A Streetcar Named Desire? How much were they both play-acting? Further still, the stage director in him wanted to set the scene, to control every aspect of what was unfolding. The room looked as if it had been ransacked. He hated mess. He went to the window once more and pulled open the curtains, forcefully as though he were stripping bare the scene. She continued watching him, the pupils of her blue eyes dilating from the assault of sunlight, just as when Mitch, in Streetcar, rips the paper lantern from the light bulb.

How did he know she was there?

Clearly, Vivien could not remember the departure of the Finches, who left for an apartment in Wiltshire Drive after she had threatened to kill their child. It was only a turn of phrase, hardly a serious threat to the infant’s life. The servants left, too, with one housemaid admitting she was scared of Vivien’s behaviour and the rituals she had begun to carry out: blasting Indian music and trying to exorcise her soul. In that sense, their fever dream had come to an end and Larry’s was only beginning.

Nor did Vivien remember the intervention carried out by David Niven and Stewart Granger, their close friends and colleagues who were part of the English expatriate community in Hollywood. Granger, known as Jimmy – his birth name – to his friends, appeared with Vivien in the play Serena Blandish at the Gate Theatre in 1938. In the early days, the unknown Granger idolised Larry and was awed by Vivien, whom he thought was very ambitious and hard-working.

In the present day, Granger was demoted by Vivien to an errand boy and he made arrangements with the studio’s doctor and collected her prescriptions from Schwab’s all-night drug store. It was Niven who served as her gatekeeper until Larry arrived, but when Niven passed out from exhaustion, it fell to Granger to coerce her into taking sedatives and chase her around when her impulses took hold. In short, they had kept her alive until Larry’s arrival. Suffice to say, she hated them both and Granger never got over the deranged look in her eyes or forgot the verbal abuse she spat at him.

Confronted by everything that had taken place and short bursts of lucidity from Vivien, Larry revealed that the studio had told him of her whereabouts. In moments of clarity, he was Larry and she was Viv, the spouses at odds with their circumstances, not the glittering couple who sold a myth to their fans – who little knew they were all being written into the fable. She bought the story and reached for a packet of cigarettes and sparked the lighter. He walked to her, through the blueish smoke, as if he had been conjured.

Looking at Vivien’s tiny frame, perched on the bed, he could not fathom the story he had been told. That she had somehow lost her mind and was wandering through the house naked, throwing money out of the window and threatening to jump out of it herself.

The final straw came when she propositioned the young secretary the studio had sent over. He suspected it was less about answering fan mail and more about chaperoning, just in case she tried to kill herself or succeeded through misadventure. There were whispers she had also made a pass at Tamara Finch, who reckoned it was done for shock value. Nobody could confirm any of it, it was all hearsay and rumours.

‘But isn’t everybody [gay]? Larry is inclined that way too,’ Vivien remarked to her friend Bevis Bawa, in Ceylon, when he confided that he was a homosexual.

‘Good Lord, I am gay too,’3 Peter added for the sake of camaraderie.

Still, Larry reminded himself that it was the secretary’s word over Vivien’s and possibly a ruse for a handsome settlement. He had been the victim of such rumours; it followed people in their profession – this, having to have a dual personality – it came with the territory and he used effeminate terms of endearment towards his fellow men, ‘Baby, Darling,’ and so forth. ‘I went through choir school, I went through public school, I was the prettiest boy in any school always, there wasn’t a prefect who wasn’t after me,’4 Larry said of his appeal to other men.

The studio executives warned Larry of Vivien’s behaviour. Her madness ricocheted off the celluloid screen during the rushes. It was the era of McCarthyism, there was a witch hunt going on: Communism in Hollywood. William Dieterle, the German-born director of Elephant Walk, supported the Marxist writer, Bertolt Brecht, and the production was delayed for three months as the State Department would not allow Dieterle to travel to Ceylon.5 In short, the studio system wanted its stars to conform to their sterile American dream. The phone was slammed down and a telegram followed. ‘Come immediately.’ The telegram said other things but in the bright, blinding sunlight in Ischia, Larry had crumpled it in his fist and forgotten about his marital discord.