Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

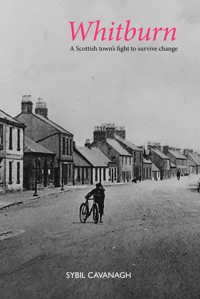

It would require many volumes to capture the variety and complexity of Whitburn's history – this book can only give a faint indication of how much has happened over the last 300 years of Whitburn's history and why the town developed as it did. So many of its people lived, died and left no trace behind but it's hoped that this book has suggested something of what their lives were like. Unknown to or overlooked by many, the small town of Whitburn in central Scotland has a varied and radical past of change and hardship. Forced to forever flow with the tide of national developments, the town's early success in the weaving industry gave way to the coal boom and the war years of the 20th century. The 1980s brought a long struggle against unemployment caused by the downfall of the coal industry, a struggle that is still being had as a result of modern-day developments such as recession, modernisation of businesses and online processes. In some ways, Whitburn is like any other small Scottish town but its radical streak and strength of heart sets it apart. Reaching across centuries, this bookis a comprehensive account of the town from birth to the present day and everything in between, showing the difficulties of surviving in an ever-changing social, political and financial climate. More than a history of a town, this is the story of its people's resilience and their constant fight to survive change.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 332

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SYBIL CAVANAGH grew up in Fife and is a graduate of the University of St Andrews. She worked in the public library service in Wigan, Glasgow and West Lothian, and along the way gained a Diploma in Scottish Historical Studies at the University of Glasgow and a fascination with Scottish and local history. She was the Local History Librarian with West Lothian Council for 26 years.

Though now retired, she is still obsessed with local history and tries to share that enthusiasm through talks, books and other publications. She was joint organiser and contributor to The Bathgate Book: a new history (2001), editor and joint author of Pumpherston: the story of a shale oil village (Luath Press, 2002) and wrote Blackburn: West Lothian’s Cotton and Coal Town (Luath Press, 2006) and Old Bathgate (Stenlake Publications, 2007), as well as booklets on subjects as diverse as Linlithgow Poorhouse, cholera in West Lothian and West Lothian’s many links with slavery and the slave trade.

She is syllabus secretary for the West Lothian History and Amenity Society, enjoys walking, is trying to re-capture her lost French, has been a church organist for 30 years (without any noticeable improvement), volunteers with the Riding for the Disabled charity and has taken up carriage driving.

First published 2019

eISBN: 978-1-912387-79-3

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by Ashford Colour Press, Gosport

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Sybil Cavanagh

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword

CHAPTER 1 ‘Full of Bogs and Marshes’: The Making of Whitburn Parish

CHAPTER 2 The Cunynghames and the Baillies

CHAPTER 3 The New Village of Whitburn

CHAPTER 4 The Church – Patrons and Grave-robbers

CHAPTER 5 Working in the New Village: Cotton Weaving and a Distillery

CHAPTER 6 Everyday Life

CHAPTER 7 Radicals, Riot and Revolution

CHAPTER 8 Coaching Days

CHAPTER 9 The Weavers – From Riches to Rags

CHAPTER 10 The Baillies Acquire Whitburn

CHAPTER 11 Mining, 1750–1850

CHAPTER 12 The New Polkemmet Pit

CHAPTER 13 ‘Shake off the Galling Chain’ – More Whitburn Radicals

CHAPTER 14 Whitburn: Occupations, Incomers and Emigrants

CHAPTER 15 Whitburn becomes a Burgh

CHAPTER 16 The Later Baillies, the Baillie Institute and Polkemmet Estate

CHAPTER 17 Railways and Roads

CHAPTER 18 The Churches After 1820

CHAPTER 19 Housing

CHAPTER 20 Industry After 1945

CHAPTER 21 Schools

CHAPTER 22 A Frozen Postman, a Bank Scandal and Some Shops and Pubs

CHAPTER 23 Poverty, Poor Relief and Self-help

CHAPTER 24 Keeping Whitburn in Order and in Health

CHAPTER 25 Whitburn at War

CHAPTER 26 Sports and Leisure

CHAPTER 27 Some Famous Natives and Local Notables

Acknowledgements

GRATEFUL THANKS ARE due to the many people who gave up their time to speak to the author about Whitburn past and present, or provided useful sources of information: Allison Gilchrist, Dave Gillan, Tracy Johnston, the Rev Dr Angus Kerr, Scott McKillop, Blair Martin, Nancy Mickel, Emma Peattie, the Rev Dr Sandy Roger, Stephen Roy, Alex Smith, Craig Statham, Meg Stenhouse, Ian Tennant, Father Sebastian Thuruthipillil, Jennifer Tortolano; and to Elizabeth Henderson, Roy Calderwood and Charlie Edwards for their practical help, support and encouragement.

The resources of the West Lothian Local History Library in Linlithgow Partnership Centre, and of the National Records of Scotland in Edinburgh were invaluable in researching this book. The author is grateful to the former for permission to reproduce some of the photographs in this book. The West Lothian Archives and Records Centre and West Lothian Museums Service at Kirkton Service Centre, Livingston, also provided much useful information, as did the National Library of Scotland and the Almond Valley Heritage Centre; and the staff of Linlithgow Library were always helpful.

A much longer version of this book showing sources of information and full references will be available for consultation from July 2020 in Whitburn Library and in the West Lothian Local History Library at Linlithgow Partnership Centre.

Foreword

DESPITE A MULTITUDE of changes during the last 300 years, numerous threads connect those who live in Whitburn today with those who have gone before. Its people have repeatedly had to cope with upheavals over which they had no control – the agricultural changes of the 18th century, the industrial changes of the 19th century, the decline of handloom weaving, the hardships of the inter-war period, the huge growth of Whitburn after 1920, the end of the mining industry and the ravages of Thatcherism. All these caused great turbulence and hardship to those who lived through them. The book records these changes and their effects on the local people but also uncovers the things that remain the same in every century – the struggle to find work, to find a home and raise a family; the urge to retain independence, to worship, to learn, to help others – and not least, to relax and enjoy life.

The south-west has always been the poorest part of the county of West Lothian, isolated from the centre of power whether that was in Linlithgow, Bathgate or Livingston. The area remains less prosperous than the more northerly parts of the county and some pockets of deprivation are to be found in Whitburn. In some ways, the town is typical of former mining communities anywhere in Scotland – a close-knit community suffering some hardship, unemployment and loss of identity, with large council housing schemes, decaying high street and tracts of degraded post-industrial land. In other ways, Whitburn’s history has proved to be distinctive – in its strong radical leanings and its lack of deference to all forms of authority. This radical streak, which has not been found to such a marked degree in other West Lothian communities, runs right through Whitburn’s past, helping it to confront and overcome its many difficulties.

Population of Whitburn

Parish

Village/Burgh

1755

1,121

1801

1,537

500

1821

1,693

1831

1,900

1841

798

1851

808

1861

1,362

1871

1,432

1881

1,200

1891

1,185

1901

1,442

1911

1,876

1921

1,971

1931

2,440

1941 (estimate)

4,000

1951

5,232

1961

5,904

1971

10,175

1981

11,965

1991

10,860

2001

10,391

2011

10,527

2013 (estimate)

10,873

CHAPTER 1

‘Full of Bogs and Marshes’: The Making of Whitburn Parish

A NOT UNCOMMON complaint heard in Whitburn these days is that Livingston has ruined Whitburn – the New Town is said to have sucked the life out of surrounding communities. As we’ll see, however, Whitburn people resented Livingston much earlier in their history! For over five centuries, Whitburn was part of the parish of Livingston. A parish was a small area where a church and a priest were based; to pay for the building of the church and the maintenance of the priest, a tax was levied on the local landowners – in effect, they paid for their own church.

The boundaries of these early parishes followed natural features such as rivers and burns and did not change greatly over the centuries. The parish was the basic unit of church life and became, too, the basic unit of local government. Scottish parishes survived intact until they ceased to have any significance after the local government reorganisation of 1975.

Livingston parish was one of the largest parishes in West Lothian – some 11 miles long and four miles broad at its widest. It extended from Knights-ridge and Dechmont Law in the east, to Fauldhouse and the county boundary with Lanarkshire in the west, and it included the area where Whitburn is situated. The church for the whole parish was at Livingston Village – almost as far east as it could be, and some ten miles away from the west end of the parish. In those days of poor roads and few horses and carts, it was a considerable journey for the people in the west of the parish to reach the church even on a mild day in mid-summer; in the worst of winter weather, it was impossible. There was certainly a chapel in the Whitburn area by the 1620s and probably before that, but the people there felt isolated from their parish kirk at Livingston Village. In 1630, Linlithgow Presbytery received a ‘supplication’ from ‘the people of the west end of the said parish, regrating [regretting] the incommodious situation of the said kirk’, and asking for the church to be moved towards the west end of the parish.

Nothing was done, so in 1647 they again petitioned the Presbytery. This time, the Presbytery arranged a perambulation of the whole parish, as a result of which, they conceded that the parish was populous enough to be divided in two. The boundaries for a new parish of Whitburn were drawn up and a site for a new church was chosen at Tounhead of Whitburn. But despite this preparatory work, the scheme fell through: national events intruded.

In 1650, Scotland was invaded by Cromwell’s forces. The kirk session records of Livingston parish stop abruptly in September 1650, when English soldiers of occupation were stationed in Livingston and other parishes. The soldiers destroyed Livingston Peel and badly damaged the church. They also plundered for food, and the kirk session recorded the eyewitness account of a young woman: ‘about fourtein days before Yule, she did see an Inglish foot soldier with two hens under his oxters.’ After the withdrawal of the English troops, the kirk session records resume in May 1651:

No Session before this day keipt by reason of the trouble, howbeit always preaching (except about a month) either at Whitburne or Ffoulshiells.

What sort of building was in use for the preaching at Whitburn is not clear. The Whitburn chapel mentioned earlier may have been still in use, or the preaching may have taken place in private houses. However, in 1658, a new ‘Meeting House’ was built at Whitburn, known simply as the New House. Its location was the site of the present South church and parts of that original building may well have been incorporated into the present church. The landowners of the whole of Livingston parish would have shared the cost of building this new meeting house.

The population at the west end of Livingston parish was growing slowly and by 1718, the meeting house needed to be repaired and enlarged. At this point, the local heritors [landowners] petitioned Presbytery yet again for Whitburn to be created a separate parish: the common people, they wrote, were

not only separated from their own Church by the Water of Almond and from all other Neighbouring churches by the Waters of Almond and Breigh, but the Interjacent Ground is so Mairish [marshy] and full of Bogues [bogs] and Marishes [marshes], that in the Winter time and Rainy seasons the ways are unpassible… and it is Impracticable for the Minister of Livingstone sufficiently to oversee and Instruct the people…

Why should the heritors have voluntarily sought the expense of building a new church? Setting up Whitburn as a separate parish would have two benefits for them: they would have a church nearby and they would be able to choose their own minister. In Livingston parish, as in the majority of Scottish parishes, the chief heritor was the ‘patron’ of the parish – in other words, he chose the minister and ‘presented’ him to the parish. If Whitburn could be set up as a new parish and the heritors jointly paid for the new church, manse and stipend of the minister, then, they assumed, they would have the legal right to choose their own minister.

Religious radicalism

In the days before political radicalism arose, radicalism was often to be found in the form of opposition to the powerful Church. Certainly, two incidences of local religious radicalism can be found even before Whitburn came into being as a village. In the reign of James IV (1488–1513), the owner of Polkemmet estate, Adam Shaw, was an adherent of the religious group known as the Lollards. In 1494, 30 prominent supporters of Lollardism (a forerunner of Protestantism) were summoned before James IV to answer charges of heresy. Shaw of Polkemmet and the others were admonished but were fortunate in that no further action was taken against them.

And during the Covenanting period of the 1680s, when the more rigid Presbyterians resisted great pressure to conform to the Episcopal form of worship and church government, the Baillie family (who had bought Polkemmet estate from the Shaws) seems to have had sympathy for the persecuted Covenanters. The minister of Livingston parish (of which Whitburn was still a part during the Covenanting period) was an Episcopalian and royalist, hated by Covenanters and strict Presbyterians. Whitburn had a number of active Covenanters, who met in the large tracts of lonely moorland which were ideal for secret open-air conventicles, hidden from government dragoons.

Covenanters saw their obedience to the civil authorities (ie the king) as a form of contract or covenant. As long as the king kept his part of the bargain (which they took to be support of true religion, ie Presbyterianism), they would keep their side (ie submission to the king’s earthly authority). So they already understood authority to be not absolute but conditional on its proper exercise. If power was not correctly exercised, then there was no obligation to obey it. This way of thinking took firm hold in Whitburn and can be traced in its subsequent story.

The desire of Whitburn people to choose their own minister fits this pattern and by making Whitburn a separate parish, the landowners assumed they would avoid patronage. The main mover was William Wardrope, probably the son of the owner of the small estate of Cult (sometimes spelled Quilt), who worked in the Grassmarket in Edinburgh as an apothecary – a pharmacist with some medical knowledge. In April 1719, he went to the trouble and expense of consulting with a judge, Lord Grange, as to who would have the patronage of the proposed new parish. The judge’s opinion was that the new parish of Whitburn would have no patron and that not just the heritors but the whole congregation (males only, of course) would be entitled to choose its own minister.

‘Excluding thereby all patrons…’

Led by Wardrope the apothecary, the Whitburn heritors formed themselves into a trust to raise funds. Money was also raised ‘by a voluntary subscription all over Scotland’ (which would have taken the form of a special offering uplifted in churches throughout the country).

Several of the heritors were liberal in subscribing, active in procuring subscriptions, and zealous in carrying out the process of creation before the Court of Teinds, from entertaining the idea that the minister was to be chosen by the parish at large.

By the start of 1722, the trustees had raised enough money to buy the meeting house and the land adjoining it and they rebuilt and extended it into a new church and churchyard. In addition, the trustees bought land for a manse and for the glebe – that is, farmland for the minister’s own use:

…these six acres of arable land going in a straight line north from the meeting house and Kirkyard to the headrig,… all lying on the West side of the said Driftloan [ie Drove Loan, ie Longridge Road] – for the ‘Gleib.’

The minister would also have the right to take turf (for building walls or roofs), and dig peat from Whitrigg Moor for the use and service of his family.

The land was purchased from the owner of Wester Whitburn, Sir John Houstoun of Houstoun in Renfrewshire, on the clear understanding that he gave up all rights of patronage over the new parish. The ministers were to be chosen by the kirk session, heritors and heads of families of Whitburn,

providing they be such as are of the presbyterian persuasion and are not grossly ignorant or profane… excluding thereby all patrons or other persons whatsomever expressly from the power of presenting, or nominating any person whatsomever to be Minister of the said Parish…

One final matter was attended to: two farms in Shotts parish were purchased, the rent from which would be used to make up the minister’s stipend if necessary, and to buy wine and bread for communion services. So the trustees were confident that they had covered every possible contingency, secured the financial future of the new parish and definitively excluded any power of patronage over it.

Convinced by the energy and commitment shown by the heritors, Linlithgow Presbytery recommended the Whitburn people to apply to the Court of Session for the new parish to be set up. This was done in 1726, and the long process was finally completed on 23 June 1731 when the Lords Commissioners of Teinds erected Whitburn into a new parish. It was some six miles long and four miles broad, with a population of about 1,000.

The first minister

Meanwhile the parishioners had not been idle. Work began on building the new church in 1729 and was finished the following year. William Wardrope, by now a surgeon-apothecary, donated to the new church two brass collecting plates and a handbell for the church officer to make public announcements through the town (like a town crier) or to ring as a mortbell to give notice of a death. In 1731, the men of the congregation set about choosing its first minister and they decided on the Rev Alexander Wardrope, minister at Muckhart, probably a cousin of the surgeon-apothecary. The ‘call’ of the congregation was sent to Wardrope at Muckhart and accepted by him. Then to the undoubted dismay of all those who had struggled so hard to set up the new parish, Sir James Cunynghame of Milncraig claimed the right of patronage of Whitburn parish, based on his being patron of Livingston parish; Whitburn being carved out of Livingston parish, he must also be patron of Whitburn. The Presbytery of Linlithgow heard submissions from both sides and came down on the side of the Whitburn folk: ‘there can be no patron of that [Whitburn] paroch’.

There the matter was shelved for the time being since Sir James Cunynghame agreed that Wardope of Muckhart was the right man for the job. But it was a dispute that would raise its head again and cause division in the parish and village of Whitburn.

CHAPTER 2

The Cunynghames and the Baillies

THE CUNYNGHAME FAMILY had acquired the barony of Livingston in the late 17th century. Until the mid-1720s, their land extended from Dechmont, across most of the area covered by the present new town of Livingston and as far west as Seafield. In 1725, Sir James Cunynghame bought the barony of Whitburn from the Houstoun family who had owned it from at least the 1540s. The purchase extended the Cunynghames’ estates to the west end of Whitburn – a huge tract of land. Being the major landowner in Livingston parish, Sir James had the right to choose its minister; a valuable right, as he could offer the post in exchange for loyalty or service of some sort and he would be sure to present a man who agreed with his own religious and political views. It was for this reason that the Cunynghames were keen to acquire the patronage of the new Whitburn parish as well.

The Barony of Whitburn

Until the mid-18th century, the owner of a barony had the legal right to hold courts and to sentence wrong-doers. By the 1720s and 1730s, these courts had declined into agricultural courts at which rents were paid and local disputes over boundaries, terms of lease, debts, etc settled. Various old documents mention the Head Court of the barony of Whitburn, and the ordinary Baron Court. These ‘hereditary jurisdictions’ were abolished in 1747; thereafter, a barony was merely an estate.

The Cunynghames and the Baillies

When they acquired Polkemmet estate c.1620, the Baillies of Polkemmet did not become the lairds of Whitburn. In fact, compared to the Cunynghames, the Baillies were minor landowners until the early 19th century. Around 1770, the Cunynghames’ Livingston and Whitburn estates had a valuation of nearly £3,000; Polkemmet’s was a mere £735. The relative status of the Baillies and the Cunynghames is revealed by the fact that Thomas Baillie was for a time the factor of the Livingston estate – a paid employee of the Cunynghames. And in that same year, 1735, William Baillie, son of the Polkemmet laird, became an apprentice wright [carpenter] in Edinburgh. None of the Cunynghame sons would have been sent to learn a trade but it was acceptable in the mid-18th century for the younger son of minor gentry like the Baillies to become a craftsman. For the wealthy Cunynghames, only the law, the army or Parliament were fit occupations for their sons.

Making improvements

The farms of the early 18th century were based on fermtouns – clusters of poor thatched cottages, whose inhabitants farmed the land together. The ground was open and unenclosed by hedges or dykes; stony, marshy and unsheltered by trees. The ‘infield’ land nearest the fermtoun was fertilised with dung and divided by deep drainage ditches into long narrow riggs – strips of cultivated land some 20 or 30 feet broad. The remains of these ploughed riggs and ditches can still be seen today, most easily in aerial photographs.

Amang the Riggs o’ Barley

Another use for the ditches between riggs is noted in Whitburn Kirk Session minutes of 29 December 1734: Margaret Bogle ‘has relapsed in uncleanness’, this time with ‘young Patrick in Easter Whitburn; that he had carnal dealing with her… in the month of July last betwixt two of his father’s bear [barley] Ridges about Mid Day, as she was going to Bickertoun to fetch a scythe…’

A stone dyke divided the infield from the outfield, which was poor quality land only fit for rough grazing. Again, there were no enclosures. Young children had the task of herding the beasts and keeping them from wandering too far away. With little winter fodder available, most animals were killed and salted in the autumn as food for the coming months. Just a few animals were kept over the winter to breed from in the spring. Houses were low, dark, smoke-filled, with thatched or turf roofs, often consisting of just a single room housing both humans and animals – the latter provided much-needed warmth. Farming in the early 18th century was a hard, punishing life, constantly on the brink of destitution and hunger should a harvest fail or a winter be exceptionally severe.

Poor land had low rental value. For example, the lease of Damhead on Polkemmet estate to William Bishop in 1738 brought Thomas Baillie an annual rental of only £9 sterling and also ‘six good and sufficient hens’ and several days unpaid work for the laird. Rent was paid partly in money, partly in kind and partly in labour and this remained common until nearly the end of the 18th century. Subsistence farming meant that little surplus produce was left that could be sold to create some profit.

From about the middle of the 18th century, landowners and farmers began to study farming in a scientific way with a view to increasing the fertility of their land and improving their livestock. Startling growth in the income yielded by estates could be achieved, provided the landowner had the money to make the initial improvements and the patience to wait several years before a profit was made. Agriculture became focused on producing a surplus for the market: profit, not mere self-sufficiency, became the aim. Open land that had been farmed in common by a group of small tenants was enclosed into large farms of regular fields, farmed by a single tenant employing a few workers. Such an agricultural revolution was not achieved without major disruption: it was the poor and powerless who suffered – the small tenants, cottars and labourers – as they were pushed off the land.

As part of the process of enclosure, the right of access to common land was lost to the ordinary people. A commonty or common muir was rough ground owned jointly by several different proprietors. It was not owned by all the people in common but many of them had the right to graze their beasts there or to dig peat and turf. As early as 1709, there had been a proposal to divide up Whitburn’s common muir at Whitrigg among the various proprietors but it came to nothing. However, the right of locals to take free peat and turf from the common muir seems to have been lost in the later 18th century; presumably because the common was divided up and fenced off by its owners.

Sir James Cunynghame’s father David was one of the early ‘improvers’ of land: in the records of the old Scots Parliament of 1705, there is a petition submitted by him to Parliament, in which he:

humbly sheweth, that he, having inclosed a considerable quantity of ground to the south of his house of Livingston, which will require the changeing of the high way, which at present goes straight by his door and is both uneasie to him and bad of itself…

He gained Parliament’s petition to close up the road that came too close to his mansion house of Livingston and to build a new road, ‘twenty foot broad, except where it goes betwixt houses…’ Like most landowners, Sir David had begun by enclosing the land around his own house and then worked outwards to the land held by his various tenant farmers. This was an expensive process, so his son James and his successors increased their income by selling off small plots of lands but retained the right to levy annual feu duty on the land.

‘A solitary house in a desolate country’

One of the first recorded feus was sold (in 1735) to William Wardrope, the Edinburgh surgeon apothecary, despite his being Sir James Cunynghame’s main opponent in the Whitburn patronage dispute. Evidently, an armed truce had been reached and relations between the two sides had not broken down completely. The land sold to William Wardrope was:

Tounhead of Whitburn with houses, biggings, yards… parts, pendicles thereon… the lands of Dykehead… the lands of Brounhill… lying within the barrony of Whitburn.

Then Cunynghame feued two plots of land to James Storrie, a Bathgate merchant: ‘that room and lands of Whytburn commonly called Yate-houses with houses, biggings, yards…, parts, pendicles’. The purchase agreement gave Storrie the right to dig peat on the common moor of Whitrigg and take turf for repairing the houses already on the land. The following year, 1736, the same James Storrie feued:

all haill the little house and yaird… bounded betwixt… his lands of Yatehouses upon the west and north, the high causey or loan leading from the miln [ie Whitburn Mill] to the Church on the East, and the highway leading from Edinburgh to Glasgow upon the [south?]

– ie the northwest corner of the Cross. (The site of Whitburn mill has vanished under the motorway – it was close to what’s now the junction of Ellen Street and Armadale Road.)

But Whitburn was not yet a village, just a scattering of houses along the high road. Accounts of Whitburn in the early years are few and far between. The earliest is perhaps that of Alexander Carlyle, one of the leading Church of Scotland ministers of his day. As a young student in November 1744, Carlyle walked from Edinburgh to the university in Glasgow. On the second day of his journey, he set out from Kirkliston some 16 miles away:

I walked to Whitburn at an early hour, but could venture no further, as there was no tolerable lodging-house within my reach. There was then not even a cottage nearer than the Kirk of Shotts, and Whitburn itself was a solitary house in a desolate country.

By a solitary ‘house’, Carlyle probably meant a ‘change-house’ or inn but the impression left on his mind was certainly that of isolation and desolation. The desolation was compounded by the lack of trees to provide shelter from the winds, the poor condition of the roads and its height above sea level (620 feet). When Carlyle started his wintry journey, he could walk easily on the frozen roads but, on the following morning:

the frost was gone, and such a deluge of rain and tempest of wind took possession of the atmosphere, as put an end to all travelling. The wet thaw and bad weather continuing, I was obliged to remain there for several days, for there was in those days neither coach nor chaise on the road, and not even a saddle-horse to be had. At last, on Sunday morning, being the fourth day, an open chaise returning from Edinburgh to Glasgow took me in, and conveyed me safe.

For the traveller then there was no public coach service and no horses for hire; only the kindness of the owner of a private carriage (chaise) allowed Carlyle to finish his journey. Given such conditions, only the very determined would travel any distance; and poor roads also impeded trade, for it was extremely difficult and costly to bring in or send out goods any distance on such bad roads.

Another difficulty for travellers was the scarcity and badness of inns. At the inn where Carlyle stayed:

I passed my time more tolerably than I expected; for though the landlord was ignorant and stupid, his wife was a sensible woman and in her youth had been celebrated in a song under the name of the ‘Bonny Lass of Livingstone’ [later collected and re-worked by Robert Burns]. They had five children, but no books but the Bible and Sir Richard Black-more’s epic poem of ‘Prince Arthur’… When I came to pay my reckoning, to my astonishment she only charged me 3s 6d for lodging and board for four days. I had presented the little girls with ribbons I bought from a wandering pedlar who had taken shelter from the storm. But my whole expense, maid-servant and all, was only 5s; such was the rate of travelling in those days.

CHAPTER 3

The New Village of Whitburn

Two more Cunynghames: Sir David and Sir William

IN 1747, Sir James Cunynghame died unmarried and the estates of Livingston and Whitburn passed to his brother Sir David Cunynghame, the 3rd baronet. David was an army officer and had also managed to raise the family’s social status by marrying the daughter of the Earl of Eglinton. Sir David continued his military career, so he was often an absentee landlord, though not an uninterested one. He administered his estates through his factors and through his wife, Lady Mary Cunynghame.

A few letters survive from Sir David to the factor of his estate, Thomas Baillie of the Polkemmet family, which show an active interest in the improvement of his estate.

I shall be glad to know if Mr Robertson has begun any repairs at the House of Whitburn. I am sure he has one of the best bargains ever man had. I beg of you to write me more frequently.

The John Robertson mentioned at the House (ie ‘change house’ – a small inn) of Whitburn is probably the inn-keeper whom Carlyle had described as ‘ignorant and stupid’ some ten years before. Since he had managed to get his lease as a best bargain from his landlord, perhaps he wasn’t so stupid!

During the 20 years of Sir David Cunynghame’s ownership (1747–67), the feuing of a few small plots of land continued but not to any great extent. By the time that William Roy surveyed the Whitburn area as part of his Great Military Survey in 1752–5, Whitburn was a cluster of perhaps a dozen houses along the high road, east of the Armadale road. The Military Survey provides the first evidence that a new village was being built in Whitburn parish but, oddly enough, it’s East Whitburn which is captioned ‘New Whitburn’ and (Wester) Whitburn does not appear at all on the map. No evidence exists of a new village at East Whitburn, so clearly this was a mistake by the military surveyors: it was Whitburn which should have been captioned New Whitburn.

Sir David died of ‘gout in the stomach’ in October 1767 and was succeeded by his son, Sir William Augustus Cunynghame, the true founder of Whitburn.

Sir William Augustus Cunynghame

Born in 1747 and educated at Oxford, Sir William, like every young man of fortune, went on the Grand Tour of Europe to study classical and European art and civilisation. After his father’s death in 1767, he became the fourth baronet at the age of 20. He was a wealthy young man who moved in fashionable circles and was something of a ladies’ man. At the age of 21, he married Frances, daughter and heiress of Sir Robert Myreton of Gogar, said to be the ‘the most inveterate swearer in Scotland. He could not speak a sentence without an oath.’ She produced three children but died young. After another few years abroad, Sir William came back to Scotland and was elected MP for Linlithgowshire in 1774.

Highwaymen

A 19th century book called Social Gleanings records an anecdote of Sir William Cunynghame and his wife while in London with a friend, Col. Graham. ‘They were driving down Park Lane to a ball or concert at the Palace, when the carriage was stopped by two footpads’ [highwaymen]. ‘Col. Graham, who was in uniform, instantly sprang from the carriage on the opposite side to the footpad, and, hurrying round, made a thrust with his sword... The... robbers made a precipitate retreat; and Lady Cunynghame’s magnificent diamonds... escaped, and the party proceeded... to enjoy the attractions and hospitality of the Palace.’

In 1767, Sir William Cunynghame’s sister Margaret married James Stuart, second son of the third Earl of Bute who was prime minister 1762–3. With such influential in-laws, Sir William moved in high social and political circles. He took another wealthy heiress as his second wife, much of whose fortune derived from her father’s estate and slaves in Grenada in the West Indies. They produced another five children. Unlike his Bute relations, Sir William was on the Whig side in politics but also something of a maverick, who ‘stood forth as the indefatigable champion of Scottish interests’. That he was hot-tempered is revealed by an incident at a political dinner during an election contest in Linlithgowshire. Lord Hopetoun (a Tory) proposed a toast, ‘Up with the Hopes, and down with the Cunynghames’. Sir William Cunynghame rose up and was pushing his way towards Lord Hopetoun to protest when William Baillie of Polkemmet stepped between them to make peace. The irate Cunynghame punched Baillie on the head, causing Baillie to cry out, ‘My lord, he’s gi’en me a gowf on the lug!’ Baillie (another Tory) challenged Cunynghame to a duel, which was fought without bloodshed on either side. In 1877, more than 50 years after Sir William’s death, his legendary hospitality was still remembered – some 15 or 20 carriages on a Sunday afternoon lining the drive up to his mansion house. This then was the man who created Whitburn – vain, wealthy, quick-tempered, patriotic and independent-minded.

New villages

The founding of new villages was taking place all over Scotland at this time: between 1720 and 1850 perhaps as many as 490 were formed. In West Lothian, Blackburn was one such and Whitburn another. Small farm tenants and labourers thrown off their land by the improvements were sold or leased land and perhaps given some materials to build a house in the new village. What was the benefit to the landowner of founding a new village? The new villagers would still be available for farm work at busy times such as harvest but had to make their own living the rest of the year. It was also a profitable exercise for the landowner: if land was feued off, money was got from its sale and the new owners had to pay him feu duty (an annual payment in perpetuity to the feudal superior). A boggy tract of worthless ground could be used for a new village, creating a market for the increased produce of the land and leading to growth of population and trade which would eventually benefit both the local community and the local landowner.

Feuing out the new village

Frequently the founding of a new village amounted to little more than the public announcement in a newspaper that a town now existed on a particular site and that ground was available for feuing. Once they had feued a piece of ground, the new residents built their houses generally with free stone and turf from the landowner’s quarries and moorland. The proprietor would allow – indeed, encourage – the local people to engage in trade within the new village, open shops or set up businesses. Some landowners built public buildings such as an inn or even set up a business to provide work for new settlers.

The first certain indication of the establishment of a village at Whitburn (rather than just a few new houses) is in the Edinburgh Advertiser of 6–9 October 1772:

Sir William Augustus Cunynghame of Livingstone having finished a large and commodious building at WHITEBURN, on the great road half way between Edinburgh and Glasgow, for the purpose of a market-place and Granaries, proposes to establish a WEEKLY MARKET there, for the sale of meal, barley, all kinds of grain, beef, flax, etc, and every other article of merchandise any person shall think proper to expose, FREE OF CUSTOM. To commence the first Tuesday of November next and continue regularly every Tuesday thereafter.

Here we have evidence of Sir William taking steps to establish a firm economic basis for his new village. By providing a market place and granaries for storing grain, he is attempting to make Whitburn the agricultural market centre for the surrounding district. To encourage merchants to rent one of his granaries, he offers to forego his right to duty on the sale of the grain ‘for some time’. The present Market Inn is a reminder of the site of the market place and granaries in the new village of Whitburn.

The same newspaper article also states:

several parcels of land, lying adjacent to the town and very convenient for feuars, will be let by roup [auction] upon the first market day.

Those interested were directed to apply to Allan Gilmour, shoemaker at Whitburn, who would show them the available sites. The advertisement for the new town of Whitburn probably appeared several times in the Scottish newspapers of the time. It was the usual way in which a landowner alerted the public to the fact that land was for sale or lease and that new residents, traders and merchants would be coming to the area, creating business opportunities for entrepreneurs.

Further evidence that a village now existed at Whitburn is to be found in a legal document of 1773 which specifically mentions the ‘village and lands of Wester Whitburn’ and also the public house on the lands of Wester Whitburn, ‘possest by Bethia Wright, relict of John Robertson, vintner at Whitburn’. And a newspaper advert for the sale of Croftmalloch farm in 1775 states that the land lies close to the ‘new town of Whitburn’. In 1778, Sir William was said to be about to set up a woollen manufactory in Whitburn – further proof of his efforts to provide employment for the village and to increase his rental income by raising the general prosperity of the area and attracting new residents.

Early villagers