Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

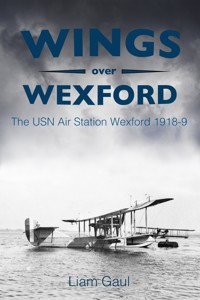

In 1918, during the final year of the First World War, the USN had a force of over 400 sailors and 22 officers and 4 Curtiss H16 seaplanes based in at Ferrybank, Wexford. The base was a veritable village with accommodation, hospital, medics, post office, YMCA Hall, radio towers, electricity generating plant and very large aircraft hangers. Although only operational for a limited period, its impact on the town of Wexford was considerable and its achievements in the global conflict were significant, protecting shipping, both naval and commercial, from the German u-boats. To mark the impending 100-year anniversary of this base, this book by local historian Liam Gaul recalls this often-overlooked aspect of Ireland's involvement in the First World War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 202

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To man’s first thoughts of flight, from when Icarus flew too near the sun and Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machine or ornithopter was a sketch on his drawing board, to the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright’s study of birds in flight at Dayton, Ohio, which led to their first flight in their engine-driven heavier-than-air ‘flyer’ on 17 December 1903 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Their flight of 120 feet in 12 seconds was just the beginning, for six years later, on 25 July 1909, Louis Blériot, in a propeller-driven aircraft, made the first heavier-than-air crossing of the English Channel. American inventor and aviator, Glenn Hammond Curtiss developed his flying boats in the early years of the twentieth century and these eventually played a leading role in the First World War, combating the enemy U-boats, especially in their brief forays off the south Wexford coast in 1918.

Front cover image: Curtiss H-16 seaplane.

Back cover: ‘Tug and Sailing Ships at Wexford Quay’, painting by Brian Cleare, 2017. (Brian Cleare)

First published 2017

The History Press Ireland

50 City Quay

Dublin 2

www.thehistorypress.ie

The History Press Ireland is a member of Publishing Ireland, the Irish book publishers’ association.

© Liam Gaul, 2017

The right of Liam Gaul to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8663 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Call to Arms

2 War at Sea

3 The Yanks Are Coming

4 The USN Air Base at Ferrybank

5 Wings over Wexford

6 The Officers and Crew

7 Rosslare Listens

8 Wexford 1918

9 War Is Over

10 Out of Sight

11 The Yankee Slip – The Aftermath

Bibliography

Notes

About the Author

Liam Gaul is a native of Wexford town and has a keen interest in history, in particular the history of his own place. Wings over Wexford, his sixth publication, gives an overview of the war and the part played by the United States Navy while it was based just outside Wexford town in 1918 and 1919. He is a regular contributor to historical journals, periodicals and newspapers and gives lectures to historical societies and local schools. He is a graduate of the University of Limerick, the National University of Ireland (Maynooth) and the Open University. He is currently president of the Wexford Historical Society. Recently, he was awarded a special medallion for his long service to Irish traditional music by Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. A member of the long-established Wexford Gramophone Society, he presents the occasional gramophone recital at its musical evenings. During the past seven years, Liam has presented a weekly summer radio programme for the Christian Media Trust on South East Radio.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the following: Beth Amphlett; Colm Campbell, Riverbank House Hotel; Mrs Maura Cummins, Waterford; Charles and Margot Delaney; Michael Dempsey; Gráinne Doran, county archivist; Laurence Doyle; Dave Fagan, Torquay; Pat Fitzgerald, Cork; Gerry Forde, senior engineer, Environment Department, Wexford County Council; Mary Gallagher; Margaret Gilhooley, Ely Hospital; Jarlath Glynn; Tomás Hayes; Ken Hemmingway; Jack Higginbotham; Tony Kearns, aviation historian; Michael Kelly; Captain Seán McCarthy, press officer, Irish Air Corps, Baldonnell Airport; Denise O’Connor-Murphy; Jack O’Leary, maritime historian; Anne O’Neill, An Post, Irish Stamps, GPO, Dublin; Mary O’Rourke, Ferrybank Motors; Angela Parle, Library Service; Frank Pelly; Joan Rockley; Seamus and Joe Seery; the staff of Wexford County Library; Bob Thomas, USA; Airman Michael J. Whelan, Irish Air Corps; and the Friday Historians – Aidan, Billy, Ken, Nicky, Seamus and Tom. To my publisher, Ronan Colgan and The History Press Ireland.

Finally, my sincere thanks to my wife and family for their interest, support and patience.

Photographic credits: Jim Billington; Ann Borg; Brian Cleare; Lisa Crunk, CA photo archivist, Naval History & Heritage Command, Washington; Charles Delaney; Nicholas Furlong; Jim Gaul, Cobh, Co. Cork; Liam Gaul; Billy Kelly, Kelly’s Resort Hotel, Rosslare; John Hayes; Irish Air Corps, Baldonnell; Michael Kavanagh; Marc Levitt, archivist, National Aviation Museum, Pensacola, FL; Dermot McCarthy; Veronica Murphy, USA; the National Library of Ireland; Cathleen Noland, USA; James and Sylvia O’Connor; Brian O’Hagan; Niall Reck; Padge Reck; Sr Grace Redmond, Presentation Convent, Wexford; Nicky Rossiter; An Canónach Séamus S. de Vál SP; Matt Wheeler, Irish Agricultural Museum Archive, Johnstown Castle; Sheila Wilmot, Duncannon, Co. Wexford.

South-east coastal map of County Wexford. (L. Gaul)

Introduction

The year 2018 marks the centenary of the United States Naval Air Base being established at Tincone, Ferrybank North,1 across the River Slaney from the town of Wexford in the south-east corner of Ireland. Although the base was just in operation for the final few months of the First World War (1914–18), it had a profound effect on the German submarine activity in St George’s Channel and the Irish Sea. Several U-boats were spotted and bombed by the seaplanes guarding the busy shipping lane, ensuring safe passage for both British naval vessels and merchant ships plying the waters between Ireland and England.

By 1919, all American personnel had vacated the air base and returned home to the USA. All buildings on the site were dismantled and sold off at auction, and soon nature had reclaimed the land and the area became a green field site once again. In the ensuing decades, the USN Air Base and its wartime activities were lost in the mists of time and memory, especially after the termination of British rule in Ireland and the emergence of a new Ireland.

Ely House and Bann-a-boo House had played an important role during the American occupation of the area, serving as the residences of the US naval officers and the centre of all planning activities during those months. Ely House has disappeared and has been replaced by Ely Hospital, while Bann-a-boo House has taken on a new form as a hotel, which incorporates some of the original building. The main frontage of the former USN Air Base is now occupied by a very successful garage and car dealership.

Many Wexford residents are totally unaware of the existence of the air base in the area a century ago but renowned singer and author, Nellie Walsh, recalled seaplanes flying over Wexford in the opening chapter of her book, Tuppences Were for Sundays:2 ‘Recently during a committee meeting of the Wexford Historical Society of which I have been a member since its inception in 1944, somebody mentioned being questioned about World War One and Wexford’s connection with it.’ Nellie goes on to say there was a laugh around the table when she described the beautiful flying boats or seaplanes landing in the harbour waters. At that time, the present Wexford Bridge did not exist and the only crossing was further up the river at Carcur. According to Nellie, the other committee members looked at her in dismay and disbelief. She went on to say, ‘I was talking of a completely lost life and maybe we should hand on our memories.’3

What was life like in Wexford and its environs at that time and what effects did the war have on the people of the area? With the shortage of food and clothing and work in the town, was there also a decline in business? Industrial unrest brought strikes for better wages and working conditions in the town’s few industries. Many Wexford men answered the call issued by John Edward Redmond MP to take up arms and enlist in the British Army to fight in Belgium and France, with grave consequences for themselves and the families they left behind. Wexford soldiers lie in unmarked graves on the Continent, with their names engraved in stone on a distant war memorial. Near the end of the war, how did the American aviators and crews interact with the local people and were friendships forged with the new arrivals on our quiet shore?

I will endeavour to record for posterity this long-forgotten era in Wexford’s past and answer the questions raised about the Americans who came to Wexford to set up and operate an air base at Ferrybank. During that year, there were wings over Wexford.

1

Call to Arms

Disagreements in Europe over territory and boundaries, among other issues, came to a head with the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand of Austria1 in Sarajevo at the hands of Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist, on 28 June 1914. Princip had ties to the secretive military group known as the Black Hand.2 This assassination propelled the major European military powers towards war. Exactly one month later, the First World War had begun. In 1915, the British passenger liner the RMS Lusitania was sunk by a German submarine, killing 128 Americans and further heightening tensions. By the end of 1915, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, Germany and the Ottoman Empire were battling the Allied Powers of Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Belgium, Serbia, Montenegro and Japan.

Many Americans were not in favour of their country entering the war and wanted to remain neutral. The desire for neutrality was strong among Americans of Irish, German, and Swedish descent, as well as among Church leaders and women. The American people increasingly came to see the German Empire as the villain after news of atrocities in Belgium in 1914. President Woodrow Wilson3 made all the key decisions and kept the economy on a peacetime basis, while giving large-scale loans to Britain and France. To avoid being seen to make any military threat, President Wilson made only minimal preparations for war and kept the American Army on its small peacetime basis as more and more demands were being made to prepare for war. The president did enlarge the United States Navy.

After two and a half years of efforts by President Wilson to keep the United States neutral, the US entered the war on 6 April 1917. They joined their allies, Britain, France and Russia, to fight in the First World War. Under the command of Major General John J. Pershing,4 more than 2 million American soldiers fought on the battlefields of France.

In early 1917, Germany had decided to resume all-out submarine warfare on every commercial ship headed towards Britain, in the knowledge that this decision would almost certainly mean war with the United States. President Wilson asked Congress to vote on the US entering an all-out war that would make the world a safer and more democratic place. The United States Congress voted to declare war on Germany on 6 April 1917. On 7 December 1917, the US declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

With the entry of the United States into the First World War, Europe witnessed the arrival of US forces in a bid to assist the Allied cause. The German U-boats were causing havoc in the English Channel. In an effort to halt the huge losses, the British Admiralty requested that the United States establish Naval Air Stations in Ireland and Britain.

A critical indirect strategy used by both sides was the blockade. The British Royal Navy successfully stopped the shipment of most war supplies and food to Germany. Neutral American ships that tried to trade with Germany were seized or turned back by the Royal Navy, who deemed such trade to be in direct conflict with the Allies’ war efforts. Germany and the Central Powers, its allies, controlled extensive farmlands and raw materials. The blockade was eventually successful as Germany and Austria-Hungary had depleted their agricultural production by enlisting so many farmers into their armies. By 1918, German cities were on the verge of starvation; the front-line soldiers were on short rations and were running out of essential supplies. The German war effort seemed to be winding down and would eventually grind to a halt.

The Germans also considered a blockade. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz,5 the man who built the German fleet and a key advisor to the Kaiser Wilhelm II,6 maintained that Germany would play the same game as Britain and destroy every ship that tried to break the blockade. Although unable to challenge the more powerful Royal Navy on the surface, Tirpitz vowed to scare off all merchant and passenger ships en route to Britain. He believed that since the island of Britain depended on imports of food, raw materials and manufactured goods, scaring off a substantial number of the ships would effectively undercut its long-term ability to maintain an army on the Western Front. Germany had only nine long-range U-boats at the start of the war, but it had ample shipyard capacity to build the hundreds needed. However, the United States demanded that Germany respect the international agreements regarding the ‘freedom of the seas’,7 which protected neutral American ships on the high seas from seizure or sinking by either of the warring sides. The Americans insisted that the drowning of innocent civilians was barbaric and grounds for a declaration of war.

The British frequently violated America’s neutral rights by seizing ships. President Wilson’s top advisor, Colonel Edward M. House,8 commented that, ‘The British have gone as far as they possibly could in violating neutral rights, though they have done it in the most courteous way.’ When President Wilson protested British violations of American neutrality, the British backed down.

German submarines torpedoed ships without warning, causing sailors and passengers to drown. Berlin explained that submarines were so vulnerable that they dared not surface near merchant ships that might be carrying guns and that were too small to rescue submarine crews. Britain armed most of its merchant ships with medium-calibre guns that could sink a submarine, making above-water attacks too risky. In February 1915, the United States warned Germany about the misuse of submarines. On 22 April, the German Imperial Embassy warned US citizens about boarding vessels to Great Britain, which would risk German attack. On 7 May, Germany torpedoed the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania, sinking her. This act of aggression caused the loss of 1,198 civilian lives, including 128 Americans. President Wilson issued a warning to Germany that it would face ‘strict accountability’ if it sank more neutral US passenger ships. Berlin acquiesced, ordering its submarines to avoid passenger ships.

By January 1917, however, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg9 and General Erich Ludendorff10 decided that an unrestricted submarine blockade was the only way to break the stalemate on the Western Front. They demanded that Kaiser Wilhelm order unrestricted submarine warfare be resumed. Germany knew this decision meant war with the United States, but they gambled that they could win before America’s potential strength could be mobilised. However, they overestimated how many ships they could sink and thus the extent to which Britain would be weakened, and they did not foresee that convoys could and would be used to defeat their efforts. They believed that the United States was so weak militarily that it could not be a factor on the Western Front for more than a year. The civilian government in Berlin objected, but the kaiser sided with his military. Germany formally surrendered on 11 November 1918 and all nations agreed to stop fighting while the terms of peace were negotiated.

The foundation of the USN Air Stations in Ireland and England, although operational for just a few short months, played an important role in undermining the dominance of the U-boats in the seas around both countries. The station at Wexford was very active and carried out many missions in search of the submarines, which operated with devastating effect in and around Tuskar Rock Lighthouse and up along the Irish and English coastlines. The presence of the American aviators was reassuring for ship owners on the coast who had been concerned about the safety of their vessels, their cargoes and especially the crews of their ships.

A ‘call to arms’ war poster.

In 1912, John Edward Redmond MP, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, was negotiating the introduction of what was to be the Third Home Rule Bill with the British Prime Minister and Liberal Party leader, Herbert Henry Asquith (1852–1928), which eventually reached the statute books on 18 September 1914. The Third Home Rule Bill had passed the House of Commons, albeit with a small majority, but was totally rejected by the House of Lords. The bill was voted on and defeated by the House of Lords again in 1913.

Dublin-born Sir Edward Carson (1854–1935), together with the Irish Unionist Party, strongly opposed the Home Rule Bill and in 1912 more than 500,000 people signed the Ulster Covenant against the passing of such a bill. To ensure that this bill was not passed and brought into law, an Ulster Volunteer Force was formed to oppose such a measure by force, if necessary.

The Home Rule Bill was passed again by the House of Commons in May 1914, when the government overrode the opposition by the House of Lords by implementing the provisions of the Parliament Act of 1911. The bill would have meant the creation of a two-chamber Irish parliament consisting of a 164-seat House of Commons and a 40-seat Senate. Ireland would retain the right to elect Members of Parliament to sit in Westminster. The bill was sent for Royal Assent.11 The king signed the Home Rule Bill at noon on Friday, 18 September, together with an Act suspending the Home Rule Bill from coming into effect, with all further parliamentary debate postponed until the war ended.

John Edward Redmond MP – war poster. (National Library of Ireland)

On his return home to Ireland on the Sunday morning, Redmond set out for his home at Aughavanagh, Co. Wicklow. He stopped his car at Woodenbridge in the Vale of Avoca, where he encountered an assembly of the East Wicklow Volunteers. Present were the two Wicklow MPs and Colonel Maurice Moore, Inspector-General of the Volunteers. John Redmond, in a short, impromptu address to the group, outlined their duty:

to go on drilling and to account yourselves as men, not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing-line extends, in defence of freedom and of religion in this war where it would be a disgrace forever to Ireland, and a reproach to her manhood if young Irishmen were to stay at home to defend the island’s shores from an unlikely invasion.

Redmond’s Woodenbridge speech became better known than his manifesto on this subject.12 Redmond pledged the Irish Volunteers to the defence of Ireland and called on Irish men to enlist in the army.

A clarion call had been sounded to participate in a war that would supposedly be finished by Christmas.

2

War at Sea

The Entente Powers – France, Britain and Russia – had a distinct advantage in the struggle to be the victors of the Great War: they had control of the seas, which gave them access to the entire globe, whereas Germany and Austria-Hungary were restricted to the areas they controlled. The British high command were convinced that the only way to end the war was to annihilate the German Army in a head-on confrontation. This decision condemned 60,000 men to certain death or maiming during the autumn in the Battle of Loos.

At sea, the battle fleets spent most of their time tied up in harbour, with occasional engagements like the Battle of Jutland fought mainly at a distance, without serious risks. The Battle of Jutland lasted from 31 May to 1 June 1916 and involved 250 ships and 100,000 men. It was the only major naval engagement of the First World War. The British Grand Fleet had a greater number of ships than the German High Sea Fleet, with 37 heavy warships and 113 lighter support ships versus the Germans’ 27 heavy warships and 72 support ships. The British Intelligence Service had also broken the German signalling codes.

The Battle of Jutland began at 4.48 p.m. on 31 May, when the scouting forces of vice admirals David Beatty and Franz von Hipper1 began a running artillery duel at a range of 15,000 yards in the Skagerrak (Jutland), just off Denmark’s North Sea coast. Hipper’s battleships took a barrage of severe shelling, but they survived, thanks to their superior honeycomb hull construction. Vice Admiral Beatty lost three battleships due to fires in the gun turrets started by incoming shells reaching the powder magazines. Beatty turned his ships north and lured the German ships on to the Grand Fleet.

At 7.15 p.m., the second phase of the battle started. Admiral John Jellicoe,2 by executing a 90-degree wheel-to-port, brought his ships into a single battle line, thus gaining the advantage of the fading evening light. Admiral Jellicoe cut the German fleet off from its home base and he twice crossed the High Seas Fleet. The German commander Admiral Reinhard Scheer’s3 ships took over seventy direct hits while his ships scored just twenty against the British Grand Fleet. This would have meant complete annihilation for Scheer’s fleet, were it not for his three brilliant 180-degree turns away from the danger. By darkness at 10.00 p.m., the British has lost 6,784 men and 111,000 tons of shipping, with German losses amounting to 3,058 men and 62,000 tons.

On the morning of 1 June, Admiral Jellicoe’s fleet stood off Wilhelmshaven with his twenty-four untouched dreadnoughts and battlecruisers. Sheer kept his ten battle-ready heavy fighting ships in port. The German High Seas Fleet had been sent home and would only be put to sea three more times on minor missions. Admiral Scheer avoided future surface encounters with the Grand Fleet due to its great material superiority and instead demanded the defeat of Britain’s economic life by concentrating on the use of U-boats in the war at sea.4

The submarine was developed from an earlier invention by John Holland (1841–1914), from Liscannor, Co. Clare. It was brought into extensive use by Germany in the First World War in the battle for supremacy and control of the conflict at sea. This ‘tin fish’ created havoc for ships off the Wexford coast, destroying thousands of tons of ships and the crews who manned those vessels. The same John Holland, a member of the Irish Christian Brothers, taught science at the Christian Brothers School in Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford, prior to emigrating to the United States in 1872. It was there that he developed his submarine, but he died in 1914 without ever witnessing the result of his genius.5

Two major sea disasters happened during the First World War, namely the sinking of the RMS Lusitania on Friday, 7 May 1915 and the Leinster on Thursday, 10 October 1918, with the loss of many lives.

The Lusitania, dubbed the ‘Greyhound of the Seas’, made her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in September 1907, powered by her 68,000-horsepower engines. The ship took the Blue Ribbon for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic. This leviathan of the seas was secretly financed by the British Admiralty and was built to specifications set by the Admiralty. In the event of war, the ship would be consigned to government service. In 1913, as war was becoming ever more likely, the giant vessel was fitted for war service. Ammunition magazines and gun mounts were installed, with the mounts concealed under the main deck timbers in readiness for the addition of guns.

‘The Sinking of the Leinster’ by Brian Cleare. (Dominic Carroll)

Two years later, on Saturday, 7 May 1915, the Lusitania