Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

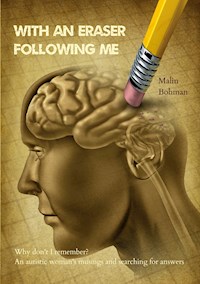

Having the ability to remember what you have previously experienced, or at least the essential parts of it, is something most people take for granted. But that is not the case for everyone, and some people lack access to their so-called autobiographical memories. A condition that is called Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory, or SDAM. Malin is one of those with this condition. In this book, she tries to describe what it means to have SDAM, how it affects her, and reflects on what the neurological causes may be and what might work a little differently in her brain. She also muses about her long and painful journey in the world of psychiatry, since it took almost 28 years before she finally received her diagnosis: autism and memory disorder. WITH AN ERASER FOLLOWING ME is thus a book for those of you who want to learn a little more about this unusual memory problem and what it can be like to live with it. It is also a book for those who may want to get an insight into how wrong things can go when knowledge and understanding are lacking in healthcare, and when a patient gets hurt, despite the best intentions. "Here is a book that is both touching and full of valuable information, that reads like a novel at times, like a thriller at others, and like a textbook too." NOUCHINE HADJIKHANI Professor of Experimental Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University. Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of my mother,

who, despite my memory problems,

will always be in my heart.

Content

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

Part I

1. To lack autobiographical memory

2. What is autobiographical memory?

3. Do we need autobiographical memory?

4. Traumatic memories – or memories of traumas

5. Living in the present

6. Living without autobiographical memory

Part II

7. My life and my contact with psychiatry

Growing up, school and work

Psychiatry contact starts

Treatment centre or not

More hospitalizations and moving

Continued struggle in the same rut

EMDR and musings on the autism spectrum

Neuropsychological evaluation, somatic problems and Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre

Part III

8. Managing life without autobiographical memory

9. What could my memory difficulties possibly be due to?

10. How is an autobiographical memory created, and what could possibly wrong with me?

11. Memories of the future

12. So what have we come up with?

Afterword

A few closing words

Acknowledgements

Appendix

Brief descriptions of brain areas I address

The importance of the body in the creation of autobiographical memories

A case report of severely impaired autobiographical memory in a woman with Asperger syndrome

Selected literature

Foreword

Memories of our own past are central to who we are, how we define ourselves, and how we take decisions and plan the future. Not being able to recall our own life events, whilst having an otherwise intact memory for facts, seems impossible to imagine. So when I first heard Malin describe to me what she was experiencing, I realized that it would be extremely difficult for me to put myself in her shoes, and try to understand how to see the world from her perspective. Hence I asked her to help me. I gave her an assignment: please write for me a few pages describing what it is like not to have an autobiographical memory.

I knew this was going to be fascinating to read, not only because it was such a puzzling topic, but also because I had had wonderful discussions with Malin, where she was sharing with me her thoughts, ideas, the books and articles she had read on or around the topic, and immediately I knew that she was what some call now an expert patient: an extremely well informed, intelligent person who would help me understand the way some people with her condition(s) experience life.

Being nursed during medical studies by Oliver Sacks’ books, I had realized early the preciousness of listening to those who experience “strange” neurological symptomatology that alters their perception of the world. And now, Malin agreed to not only share this with me, but even go further and share with the world what it is to not only suffer from autobiographical memory difficulties but also to have an autism diagnosis – preceded by a series of inaccurate psychiatric diagnoses that had made – and in some instances continue to make – her life nightmarish at times.

Of course, the “few pages” I had asked for quickly started to become many more, and I am so excited to see that they eventually turned into a book! I am sure this must have been a very difficult exercise for her, but she never gave up, and was always in the quest of making her text better, more precise, expressing what she exactly meant, and I have to say how impressed I am by the results. Malin is indeed always seeking to make things right, and it became a subject of laughter between us when she would write to me that the final version was now written, only to a few days later let me know that she “only needed to make minor changes” here or there. She has been polishing this manuscript with utmost attention, and the results speak for themselves: here is a book that is both touching and full of valuable information, that reads like a novel at times, like a thriller at others, and like a textbook too.

So I have to say “Thank you, Malin!”, for agreeing to work so hard to share your experience with the rest of us, and to make us aware of what it is to not only suffer through your many conditions but also to have been labelled a psychiatric patient, with all the difficulties that it can generate when trying to deal with physical ailments. I am sure that many will recognize themselves here and there, in their struggle with being autistic, with having memory difficulties, with being a patient in the system. And all readers will appreciate the very poignant content of this story of a journey through the meanders of an exceptional brain.

Nouchine Hadjikhani Professor at Sahlgrenska Academy at Gothenburg University Associate Professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston

Preface

“Sometimes I have seen it all as being unreal, a dream to wake up from, a nightmare that has a soul in my body. Sometimes I have seen it all as a plague to endure. When, in fact, it is just a different reality.”

Åsa Jinder

For many years, I have been thinking about why it seems almost impossible for me to get hold of memories of my own life – my autobiographical memories – and tried to find answers to this question. But unfortunately, I have not been able to find any solution among the caregivers I have had contact with over the years, nor in any of the many books I have read. At least no answers that have felt right within me, either emotionally or intellectually.

I have not either found any accurate descriptions of how it can feel and what it can be like to live with such difficulties, either in works of non-fiction or fiction. Or rather, I did come across some glances, sometimes – mainly in fiction books – but then, as I said, it has been just glimpses as well and nothing that described the situation in more detail.

I have been longing for answers as to why I have these difficulties. But even more so, I have been longing to find descriptions that I could really recognize myself in. Descriptions that might then have made me feel less alone and unsuccessful, as I have done over the years – and unfortunately still often do. And of course, I have also been longing to have my difficulties properly confirmed somewhere, to be believed and understood. At least to the extent that it is possible to understand such problems.

Therefore, it was quite remarkable that when I got in touch with Christopher Gillberg and Nouchine Hadjikhani, my story was then not only believed but also taken seriously. Later, they also gave me a more solid confirmation by showing that it was possible to see physiological abnormalities in my brain that could explain my memory difficulties. Thus, this helped me also to understand that this is not something I can modify, and it is not something I should either be ashamed of or feel so unsuccessful about.

After Nouchine showed me a study done in 2015, I have also understood that memory researchers have begun to take an interest in this memory problem after all. And I have also come across several people with similar difficulties online, so I now understand that I am not alone in having them. I should not say that the latter feels good, because this is not a difficulty I wish for someone else, but it still brings a sort of relief. The sad thing is that there is still so little information to be found about this kind of problem. Yes, it is almost non-existent.

So when Christopher and Nouchine suggested that they write a case report of me, I didn’t say no but instead began to try to answer the questions Nouchine asked me. However, I had not expected my answer to be this long, even though I am not exactly known for my good capacity to be brief. And I really had no idea that it might even become a book. No, I probably would not have dared to start answering at all then.

I should probably also explain how I composed this text, how I was thinking when I wrote it. It can probably be best described by the fact that I usually think a lot. When I puzzle over a subject, a lot of ideas and questions usually come up. And over the years, this has also been the case in terms of wondering about my autobiographical memory. This is why I list in this book thoughts I have had over the years, lots of ideas, and even though many may be both a little wacky and inexperienced, I have not let myself been stopped by it but simply let my brain spin freely. And that despite the risk that it might then get a little crazy sometimes. You who possess excellent knowledge of our brain and its functions can thus feel warned. However, I can comfort you with the fact that in the last chapter, I will also give an account of at least some of what the researchers have found out. And in addition, you will in the appendix also find the case report I mentioned.

When I muse, I often do so in the form of a kind of conversation with myself, and this is how I have worked with this text. So sometimes, this becomes almost a discussion between two different Malin: one much younger and more sensitive version and one who is more distant and analytical. One who also possesses some knowledge in both psychology and neurology, but who over the years has come to the realisation that she should also take the time to have a dialogue with the younger version because they both have a lot to learn from each other.

Writing this has certainly been very useful to me. It has been a way for me to get all my thoughts gathered in one place, but also it has given me the opportunity to write about and process at least some of what I have experienced and gone through in psychiatry. Sadly, psychiatry mistreated me by misdiagnosing me, because the knowledge and understanding of many of my difficulties didn’t exist then. But I will not deny that I also hope to be able to reach out to some of you who experience similar problems, especially if you, like me, feel very alone about having such difficulties and perhaps even feel both fear and shame about them. I hope that those of you who may recognize yourselves in what I describe here may then be able to feel a relief in the knowledge that you are at least not alone, but that there actually are several of us who share this reality.

Another hope I have is that you who read this but don’t have similar difficulties – with memory, among other things – may still be able to gain an increased understanding of what it can be like to live with such a condition. That we all are different, and many of us therefore don’t fit into all these frames the surroundings so often consider obvious, right and “normal”. Frames which I, for example, have used violence on myself in my attempts to fit into. And especially to caregivers, I would like to say that now is high time to really start listening to what your patients have to say – if you have not already done so – and try to see things from a slightly different perspective. It is only then, I believe, that increased knowledge and understanding really can emerge. For although we live in the same world, we are far from all living in the same reality.

Introduction

“What does it mean to lack autobiographical memory?”

How do I answer that question? When I got it addressed to me, I was once again wholly unresponsive. Yes, I felt like I was empty inside, and that even though I also have been thinking about the issue for so many years. It is so difficult to answer, by which I mean not only in concrete or theoretical terms but also from a more personal perspective. Yes, it is rather more challenging to take on seen from the latter, I would say, at least for me, because the answer then becomes so emotionally painful.

It has now been a couple of weeks since Nouchine asked me the question, and my memory of the meeting itself has already started to blur at the edges, but this feeling of emptiness I still bear with me to some extent. Because I always do.

Part I

1

To lack autobiographical memory

“Memories, even bittersweet ones, are better than nothing.”

Jennifer Armentrout

“What does it mean to lack autobiographical memory?” The well-known feeling of fear and embarrassment quickly followed the emptiness that immediately appeared when that question was asked to me, for this is a question that both scares me and makes me feel very ashamed about myself.

I feel ashamed that I don’t remember people who meant a lot to me, who I both have liked and been liked by, in a way that I probably should do. Ashamed not to remember significant events in my life, whether they were filled with joy or sorrow. Especially if these events were also important to other people in my immediate surroundings, such as deaths, accidents, births, baptisms, confirmations, or significant holidays and family events in general.

As I now muse over the question, I also begin to fear that I might be wrong. And that fear is accompanied by a shame that I may be telling lies and complaining unnecessarily, especially as there are people who have much more severe memory difficulties than I have. I cannot for sure know how people around me remember their lives and what they have been through. Maybe it is not that much different from what I experience? Perhaps I just imagine that I have a genuinely deplorable, bad autobiographical memory? Perhaps I remember my life without understanding it, and maybe just turn a blind eye to something I can actually see?

I think that the latter fear is almost absurd, yet I cannot entirely dismiss it. Especially since people around me, including caregivers, usually seem to have such a hard time not only understanding what I am describing but also believing that it might be true. It is so easy to begin to doubt oneself and one’s experience when no one else seems to see or understand it.

But I can see that other people seem to have access to their memories in a completely different way than me. I can be absolutely amazed and even a little jealous – yes, I must unfortunately admit that – when people describe various events they have experienced, and how detailed these descriptions can often be. But what fascinates me the most is still what they look like when they tell me this, because it is usually clear that something happens within them when they think back on what they have been through. And that is truly something I would like to experience myself.

So, despite these doubts, fears and a rather harsh and punitive superego, I, therefore, dare to say that the fact remains: I don’t have access to a functioning autobiographical memory. Okay, I don’t entirely lack one, but it works miserably poorly, to say the least. And it is also not just that I don’t remember certain parts of my life. No, this difficulty in creating, storing or perhaps recalling memories is something that continues to this day, even though, for example, events from last week are at least slightly less blurred than those that took place a couple or three months ago.

What I experience could be perhaps best described as if, for some reason, I were pulling a large eraser after me, which slowly but surely wipes away my autobiographical memory traces. Or at least huge parts of them.

On the few occasions that I have tried – and still try – to tell about my difficulties, really struggling to find the words to describe both how badly I remember what I have been through and how bad I feel about it, I have often been waved away by those I was talking to. As if a bad autobiographical memory is not something to worry about. There is no real understanding, and instead, I often get a pat on the back in the form of words like: “But dear, no one remembers everything they have been through in life”. When I get such a reply, I understand that I have failed to explain once again, yet I still don’t have a good answer to how I should do to succeed in conveying this message.

If I just say straight that I cannot remember anything from when I was in a specific situation, I get, for example, the answer that since I just told that I was there, then I obviously can remember that anyway. To continue to struggle with trying to explain that I know that I have been there, but just as damn cannot remember it, can unfortunately often feel quite meaningless. To try to explain that there is a big difference between knowing and remembering – at least for me. To know is just a factual memory like any other, and it might as well be about someone else. It does not feel like an autobiographical memory, because it does not resonate in the body.

I have often tried to describe it this way: What I tell about my life might as well be what I would tell about the life story of a character in a novel; knowledge about facts I have memorized from a book, and therefore something that does not feel either alive or real within me. And although I still have access to a lot of facts about my life – like where I have lived, gone to school, what I have worked with, important events in my family’s and my own life, etcetera – these bits and pieces of facts are, to say the least, diffuse and meagre. And lots of the parts are also just missing altogether.

The life stories that I have available and that I am trying to hold on to are in an unstable equilibrium, resting on very few fact pillars placed a little here and there. These pillars are surrounded by huge black areas that I risk falling into if I am unlucky, or when the energy to keep all in balance is not quite enough. And I probably don’t need to point out that this is a scary situation to experience, to say the least.

Suppose that I were also to try to describe the diffuse and scanty traces that I have access to. Then my knowledge would perhaps be best likened to tattered, black-and-white photographs of very poor quality – unlike the (good) autobiographical memory’s large 3D prints in colour, with emotional background music.

I don’t know how many times I have been asked when this memory problem began, or at least when I first noticed it, but the answer has undoubtedly not changed over the years and at the time of writing, it is still the same: Unfortunately, I don’t remember. The only thing I can say with certainty is that I have it today and that I believe that it is nevertheless a problem I have had with me since childhood, at least to some extent. I cannot piece it together logically otherwise.

But I can read in my psychiatric medical record that I have thought about this and sought answers at least since the late 1990s. And since I can also read there that I started going into therapy in the early 1990s, it probably means that I became aware then, if not sooner, of my difficulties in some way. Going into therapy without talking about yourself and what you have been through should not work well, I mean.

Although the shortcomings in my memory thus cover my entire life, I have noticed that there is still a distinct difference between my memories – or rather my knowledge – from before and after the age of twelve. Before that dividing line, I don’t have access to any memories of my own, but only to knowledge based on information that others have told me. After that, however, I also begin to have access to information that can only originate within myself. But sadly, it is still not memories like the ones I really wish I had access to. Essentially all of them – if not even all – are only diffuse I know that-memories.

I understand that all this can be difficult to understand and imagine if you don’t have any significant difficulties with your own memory. I myself have a hard time imagining what it would be like to have access to a good autobiographical memory, even if that achievement is probably easier for me. Because, after all, I have access to a pretty good semantic memory. Meaning that I have a memory system that I can at least use as a comparison.

On the other hand, I find it difficult to understand why this problem is usually waved away so lightly. Is not one’s autobiographical memory worth more than that? Is it not something that is important to have access to? Yes, it is, but most people don’t seem to be aware of it. They don’t think about it further, but only take it for granted because it is available.

2

What is autobiographical memory

“Memory is the diary we all carry about with us.”

Oscar Wilde

Before pursuing, I must try to describe and understand what an autobiographical memory actually is. And primarily how I define it, because I am not sure that even memory researchers entirely agree on how our various memory systems should be divided and referred to.

However, whatever the case may be, it is clear that we possess many different memory systems, that I took the liberty of briefly describing in a very simplified figure on the next page, where the dotted arrows are my own musings (explained in the following pages).

First, memories can be divided into explicit (or declarative) and implicit (non-declarative) memories – where the explicit ones are those that are deliberately recalled, as opposed to the implicit ones that don’t need any conscious recalling. Both explicit and implicit memories can then be divided into short- and long-term memories.

Figure 1: Different memory systems and how they can be divided, where the dotted arrows are my own musings.

Before memories can be sent to long-term storage, they must first be processed in our short-term memory. That memory works constantly, so working memory may still be a better term. Only part of the information is then passed on from here. Most of it is only temporarily used when we need it; things are registered only briefly and then forgotten. However, only information that we pay attention to is processed in short-term memory, so some implicit memories can actually take a shortcut into long-term memory, as we can, for example, encode (store in) impressions unconsciously.

Regarding the difference between working memory and short-term memory, memory researchers certainly don’t seem to agree on either the names or the definitions. Some believe that working memory and short-term memory are the same thing, while others think that they are separate. But because the line between them is so fluid, researchers have, to my knowledge, not been able to agree on what an exact division would look like. For simplicity, I am therefore considering them as broadly similar and use these two terms as if they were synonyms.

The implicit long-term memory includes perceptual and procedural memory. Knowledge about how we perform different things is stored in procedural memory, such as riding a bicycle, swimming, tying shoelaces, etcetera. On the other hand, in the perceptual memory, information that allows us to identify objects and orient ourselves in the outside world is stored, together with memories of different sensory impressions, such as visual and auditory impressions, tastes and smells. Thus perceptual memory helps us recognize, for example, a chair and a table and understand what they are to be used for, or allows us to both recognize and recall the taste and smell of, for example, an orange.

Therefore, shouldn’t emotional memories be considered as part of the perceptual memory? Because our feelings are experiences of biological changes in our body, along with our thoughts and our way of thinking. Or, to put it in the words of neurologist Antonio Damasio: “A feeling is the perception of a certain state of the body along with the perception of a certain mode of thinking and of thoughts with certain themes.”

Regarding the explicit long-term memory, a Canadian psychologist named Endel Tulving in the early 1970s put forward his view that this should be divided into two parts: The semantic and the episodic memory, where he, by the latter, certainly meant our autobiographical memory.

Semantic memory stores information and knowledge about everything between heaven and earth. It may be described as our inner reference book for mainly impersonal facts. Such as names of countries and people, knowledge of the meanings of words, times of various public events, etcetera. Or why not a description of our neighbour’s recent holiday trip. On the other hand, in episodic memory, personal facts are stored; information about events and episodes that can be placed in time and space and that are concretely connected to our own experiences. For example, here is much of the information needed to describe our own recent holiday trip stored.

Despite the similarities – that they are both something like reference books – Tulving noted that there are differences between these two memory systems in terms of both how the processing of the information is carried out and what type of information is processed. But he also noted an interdependency between the two systems: a new episodic memory is influenced by information already present in the semantic memory. The memory must first pass through the semantic “area” before it can settle down in the episodic “area”. And vice versa: semantic memory can bring new information to life through its association with the episodic memory.

When I write “area”, it sounds as if our memories would have their very own given place, but that is certainly not the case. Many different areas scattered throughout our brain need to work together to be able to do things that often feel so easy for us.

The definition of episodic memory has changed slightly over the years and went from being knowledge of what, where, and when something personal has happened, to also include the actual experience of thinking of oneself in a scenario. Hence for a memory to be called episodic, there is a need for knowledge and awareness that we ourselves have experienced what we remember.

Is not autobiographical and episodic memory the same thing, then? Well, according to Tulving, it probably is, even if he sticks to the more neutral term of episodic memory. But if you look at what some other researchers say, I honestly don’t know; there seem to be disagreements regarding both definition and name.

Personally, I have some objections to the fact that episodic memory is considered an explicit memory, even though I am well aware that episodic memories can be deliberately recalled. After all, such episodic memory also contains an awareness that it is something that we ourselves have experienced, i.e. that it is associated with some kind of feeling, whether conscious or not. And it is also accompanied by an emotional charge, whether we can recall the feeling along with the memory of the event or just remember how we felt when the event took place. Moreover, it usually also includes the memory of some sensory impression, such as a sound, a taste or a smell. So should not autobiographical memory instead be placed in some borderland between explicit and implicit memory?

And if you compare the terms – episodic and autobiographical – I think there is a huge difference between an episode and an autobiography. Biographies of our lives contain so much more than just the episodes that we can recall. Such as when and where we were born, and various facts that others have told us about how we have been as people and what we have been through. Things that we don’t remember ourselves but still include our life stories. So, even though the definitions largely coincide, I still think that autobiographical memory is something a bit different: It is a memory in which feelings and episodic, semantic and perceptual information are mixed together. But in autobiographical memory, there is also the awareness that this is actually something that we ourselves have experienced. An awareness that gives a feeling, a kind of resonance in the body.

One characteristic of autobiographical memories is that they may differ in the degree to which they resemble copies or are reconstructions of the original event (Cohen, 1996). We can thus remember events from an observer perspective or from a field perspective. When we recall the memory from an observer perspective, we stand in the audience and see the event from a distance and can thus better reflect on it. If, on the other hand, we recall the memory from a field perspective, we see the event as when it occurred, that is from the perspective that we had when we were there in the middle of the action.

Observer memories cannot, therefore, be copies of the original event; they must be reconstructions. While field memories are more similar to copies, and hence also tend to be more vivid. Usually, the fresher a memory is, the more resembles a copy, i.e. a field memory. In contrast, older memories over time increasingly take the form of an observer memory. If it is a really emotionally charged memory, it is most likely that it is also seen from a field perspective, and this is especially true for traumatic memories.

It may have to be pointed out that what we are talking about here are events that we remember. Of course, but still. For it is the fact that most of what we do and experience every day, if it does not go entirely without a trace, it is in any case only registered briefly and then dismissed to the land of oblivion. These experiences never even become long-term memories. There are actually very few events that we consider worth saving as autobiographical memories, and what helps us determine that relies on our feelings. Because feelings and emotions are an excellent memory glue.

What is also worth considering is that in addition to the “ordinary” ability to create – or whether it is about recreating – autobiographical memories, some individuals have extreme variations of it. Like those (very few) people who have a real super memory and can talk about what they have done almost every day of their lives. This is called hyperthymesia or HSAM (Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory). And recently, it has also been discovered that the opposite condition exists, which is called Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory. People with SDAM instead lack access to their autobiographical memories, even if they have a well-functioning semantic memory. One can undoubtedly say that I have a version of the latter.

We collect most of these memories in more general category groups and place them during different times of our lives. Such as our earliest childhood, school days, family or work life, etcetera. Details are, therefore, the first thing that gets to meet our inner eraser. What remains is a more general picture with a certain, albeit weak, perhaps even unconscious, emotional charge.

Say, for example, that we are given the task to try to imagine a ride we had in a car. We don’t remember all the details of either the car or ourselves, do we? Or all the details of everything that was around us? No, most likely, we can “just” recall the feeling around such a journey in general. If we found it pleasant or stressful to drive, if we would have rather sit next to the driver, or maybe we had preferred not to go at all because we easily get motion sickness, etcetera. The car ride that may still stand out a little extra, and that we remember better than this one, is the ride where something out of the ordinary happened, which made us feel more than we usually do on a regular drive. Maybe we saw a collision or were ourselves involved in some accident. Yes, we might even have collided with our future partner, etcetera. Because feelings and emotions, as I said, are excellent glue.

Speaking of the fact that details are usually the first thing being forgotten, it is actually a very clever product of our brain: not to memorize everything, but instead categorize and bring together in different groups. Of course, we can often be a bit frustrated when we cannot remember certain details in different situations, but the opposite would probably not feel very good either.

To continue on the car theme: Remembering all details could lead to the fact that when we, for example, need to make a quick idea of what a car is, we would run into the risk of getting caught up in some endlessly feeding memories of all the cars we have ever seen – size, colour, brand, model year, etcetera – but also of the different situations in which we have seen them, instead of just quickly painting a more general picture within us. Personally, I was now thinking of a money-devouring block on four wheels.

This ability to categorize and generalize also means that we can think abstractly and thus are able to, for example, understand more easily the meaning of metaphors and allegories, that I have such a fondness for. This is something that a person with a more extreme detailed memory may instead have difficulty doing. There is even an expression of just that: “Not being able to see the wood for the trees”.

Therefore, it is good that we forget as many details as we do because otherwise, we would find it difficult to grasp what is really important for us to remember. And it can be anything from everyday little things, like the fact that we had decided to meet with a friend or what we needed to shop, to what is actually most important to us – namely, what ensures our well-being or even our survival. Then details are often less important; instead, it is good enough that we remember how something has felt for such memories to be able to guide us in the future. Whether it was boring or fun; painful or pleasant; threatening and intimidating or offering protection and comfort, etcetera.

For example, if we read several fantasy books or saw similar films and liked them, we then have created memories that can quickly guide us the next time we want to buy a book or see a movie. And if we felt bad when we went to various amusement park attractions or in some vehicles, it will later remind us that it may not be worth the effort to try it again. Or we may have experienced something really nasty on our early (or late) jogging, which then makes us choose to exercise at a different time next time.

But to return to observer and field memories, it is probably true that memories are usually seen from a field perspective when they are fresh, to then increasingly move on to being seen from an observer perspective. For most of us, it is probably still easier to first remember how we ourselves experienced the event – what we thought about it, felt, etcetera – before we can then also begin to reflect on the event in general and what was happening around us. Then perhaps we can even think about how other people may have experienced it all, and thus be able to re-evaluate our own experience and change the memory somewhat.

However, it is clear that there must be exceptions here too, and when I think about it now, I am actually one of them. For example: At first, I only tried to recall the memories of the traumatic events that I experienced from an observer perspective; then, I increasingly tried to move on to a field perspective and then also incorporate the feelings I probably felt at the events, something I would rather not have to do again; finally, I would retake the role of an observer, allowing me to reflect more easily on what had happened.

What is described here is mainly about very emotional memories, both negative and positive ones, but what about the more neutral ones? Well, I am myself probably always trying to see what I experience from an observer perspective, and may even have a hard time doing things differently. I am an observer who tries to figure out what is going on around me. And who then also tries to see more of how other people might experience the whole thing, rather than put effort into figuring out what is really happening within myself. Something that is not very successful all the time, but I will return to that later. If I do so in most situations, is it unreasonable to think that many other people are doing something similar with at least more neutral experiences? Neutral memories are also the most volatile, the easiest to both change and erase.

Our memories change over time. They are actually changing a little every time we recall them, because the new knowledge and experience we gain over the years also affects our memories. And even the emotional state we are in at the moment affects the memory we look back on. The fact that our memories change like this can make them a little deceptive. But at the same time, this change is usually to our advantage because we ourselves are also continually changing, and memories may need to change somewhat to fit into our current life situation. Our memories should help us. It is not we who should adapt to them.

When it comes to really painful or traumatic memories, this ability to change is absolutely fantastic, as, over time, we may be able to look back on these events without being tormented as much as when they were fresh. Yes, those memories may then even strengthen us when, for example, they give us knowledge of what we have managed and been able to cope with. Naturally, this change also applies to positive memories, and if we have experienced something really gratifying, we will probably first remember it from this more exciting perspective. But such feelings usually don’t last very long and will therefore not do so in memory form either. So when the euphoria has subsided, we will probably find it easier also to remember other details of the event.

Memories can naturally also be changed in the other direction, since we really want to stick to what has been positive and pleasant. For instance, our parents tend to remember how much joy we gave them and how happy and talented we were as children, and they don’t like to talk about all that must have been very stressful. Many events may not have been really as fun and exciting as we would like to remember them, but instead, we probably have for various reasons pimped up the memory a little more as time has gone by. A good example is how the little fish we caught on the holiday just seems to get bigger every time we recount the event.

3

Do we need autobiographical memory?

“Everybody needs his memories. They keep the wolf of insignificance from the door.”

Saul Bellow