Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

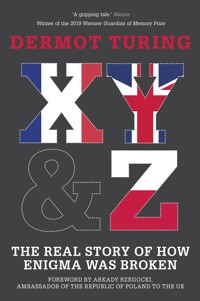

It's common knowledge that the Enigma cipher was broken at Bletchley Park, but less is known of the background: an exhilarating spy story of secret documents smuggled across borders, hair-raising escapes, Gestapo interrogations and betrayals. At the heart of it is the decisive role of Polish mathematicians and French spymasters who helped Britain's codebreakers change the course of the Second World War. X, Y & Z is the real story of how Enigma was broken.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

La collaboration avec le Service britannique n’a pas cessé pendant toute la guerre et de la façon la plus intime qui se puisse rêver.

Gustave Bertrand, report of 1 December 1949

[Collaboration with the British Service continued uninterrupted for the whole war, and in the closest manner imaginable.]

First published 2018

Reprinted 2018, 2019

This paperback edition first published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place,

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, gl50 3qb

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dermot Turing, 2018, 2019, 2021

The right of Dermot Turing to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8967 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

List of Maps

Foreword

Dramatis Personae

Timeline

Introduction

1Nulle Part

2 Enter the King

3 Mighty Pens

4 The Scarlet Pimpernels

5 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix

6 Monstrous Pile

7 The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side

8 Into Three Parts

9 A Mystery Inside an Enigma

10 Hide and Seek

11 The Last Play

Epilogue

Appendix

Notes

Abbreviations

Select Bibliography

LIST OF MAPS

Partition of Poland before World War One

26

Poland 1922–39

80

Partition of Poland 1939–41

126

Gwido Langer’s escape route 1939

135

France 1940–42

164

Eastern border of France with Spain.

233

Poland after 1945

272

FOREWORD

By H.E. Prof Dr Arkady Rzegocki, Ambassador of the Republic of Poland to the United Kingdom

On 23 March 2018 I was pleased to be the guest of honour at Bletchley Park, where H.R.H. the Duke of Kent ceremonially opened a new permanent exhibition called The Bombe Breakthrough, which explains how messages encrypted on the Enigma cipher machine were broken using novel machine techniques. The exhibition describes not only the work done at Bletchley Park itself, but also the foundations laid in Poland before the start of World War Two. The Polish Embassy contributed a full-scale replica of the Polish bomba machine, illustrating that the development of machines for code-breaking began in Poland.

The fact that the Enigma code was broken is now well known in both Britain and Poland, but what people know is surprisingly different in the two countries. In Britain, the story is about the achievements of Bletchley Park, centred on the work of Alan Turing, and how the decryption of Enigma messages helped the Allies to victory and shortened World War Two by as much as two years. In Poland, however, the story is about the triumph of mathematicians, especially Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski, who achieved the crucial breakthroughs from 1932 onwards, beating their allies to the goal of solving Enigma, and selflessly handing over their secret knowledge to Britain and France. It is the story of a relay race, with the baton changing hands at crucial moments. When America entered the war, the Enigma secrets were once again passed on.

All the countries involved have much to be proud of, and the Enigma story deserves to be told from all the viewpoints. This book will help ensure that the achievements of the Polish code-breakers are better understood in Britain. But there is a wider significance than balancing the narrative. At the heart of the success against Enigma, and its contribution to the outcome of World War Two, was international cooperation in the field of intelligence. Poland, France and Britain (and, later, the United States) were partners in an intelligence-sharing network, contributing knowledge from various sources towards a common goal. The spirit underlying the Enigma relay race remains relevant, with intelligence cooperation continuing to be a matter of vital importance in the face of more modern threats to security. It is in that spirit the Polish Embassy has supported the exhibition about Enigma code-breaking at Bletchley Park.

Meanwhile, the dramatic story of the Polish code-breakers and their colleagues, and what became of them, is set out here. I hope you enjoy this fascinating book written by Sir Dermot Turing, the nephew of Alan Turing. Sir Dermot has, for a number of years now, cooperated closely with the Polish Embassy, historians and academics to tell the true story behind these crucial events, that shaped our modern history. I am very grateful that this story has been told from both sides. It is key to a better understanding of our common history.

Arkady Rzegocki

The Embassy of the Republic of Poland

47 Portland Place

London W1B 1JH

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Polish

The Assault on Enigma

The Other Exiles

The Wider Picture

† Perished in the Lamoricière shipwreck

The French

The Service de Renseignements

The British

GC&CS

MI6

‘World War Two’s greatest spy’

Pronunciation

Despite the grumbles of English speakers, Polish is largely phonetic, and strings of consonants are not so daunting once the principles are mastered. The emphasis is almost always placed on the penultimate syllable.

c

ts, as in hats, unless followed by i, when it is softened as in chip

ch

soft ch, as in Bach

ć, cz

hard ch, as in chop

dz

j or ge, as in judge

ę

en, as in penguin

j

y, as in yes

ł

w, as in how

ń

as ñ in the Spanish mañana, or ni in onion

ó

oo, as in hood

ś, sz

soft sh, as in shot; s followed by i is also softened

w

v, as in van

rz, ż

soft z, like the ‘s’ in pleasure; z followed by i is also softened

TIMELINE

France (X)

Britain (Y)

Poland (Z)

Germany

1918

23 February

Patent filed for Enigma cipher machine

11 November

Armistice Day – cessation of hostilities in World War I

Independence Day

1919

28 June

Treaty of Versailles fixes Western border

1 November

Government Code & Cypher School founded

1920

April

Russo-Polish War begins

14–20 August

Battle of Warsaw

1921

21 February

Franco-Polish defence treaty

18 March

Treaty of Riga fixes eastern border

1926

Mid year

Commercial Enigma machine acquired for study

Commercial Enigma machine acquired for study

First naval Enigma messages observed

1929

15 January

Langer head of radio intelligence; Cryptology course at Pozna´n begins

25 April

Bertrand joins Section du Chiffre

1930

31 May

Wehrmacht model Enigma machine in service, with plugboard

1 November

Section D of Service de Renseignements (radio intelligence) created

1931

1 November

Rex meets Asche

7–11 November

Bertrand transfers first haul of documents to Langer

1932

December

Rejewski’s break

1933

30 January

Hitler becomes Chancellor

1934

26 January

Germano-Polish non-aggression pact

1936

1 February

Enigma rotor order changed monthly

7 March

Rhineland reoccupied

1 October

Enigma rotor order changed daily, cross-pluggings altered

1937

24 April

Knox breaks Spanish Enigma

22 October

Menzies meets Rivet

1 November

New Enigma reflector in use

1938

September

Scarlet Pimpernels begin

15 September

Enigma ‘indicator’ becomes message-specific

25–30 September

Munich Agreement on Czechoslovakia

15 December

Two new Enigma rotors in service

1939

1 January

Cross-pluggings increased to between 7 and 10

9–10 January

X-Y-Z conference in Paris

10 February

Denniston reports that a sufficient supply of professors is available

31 March

France and Britain ‘guarantee’ support to Poland

26–27 July

X-Y-Z conference at Pyry

23 August

Molotov–Ribbentrop pact

1 September

Invasion of Poland by Germany

4 September

Turing arrives at Bletchley Park

17 September

Invasion of Poland by USSR

September-October

First evacuation of Polish code-breakers to Paris

1940

20 January

PC Bruno established

18 March

Prototype Bombe installed at Bletchley Park

1 May

Double encipherment of indicator ceases

10 May

Invasion of France by Germany

24 June

Second evacuation of Polish code-breakers, to Algeria

25 June

Franco-German armistice

10 July

Battle of Britain begins

October

PC Cadix established

1941

22 June

Germany attacks Russia

11 December

Germany declares war on USA after Pearl Harbor

1942

9 January

Lamoricière sunk

8 November

Operation TORCH begins;

Third evacuation of Polish code-breakers, to Côte d’Azur

11 November

Occupation of Zone Libre

1943

27 February

Rex arrested

January–July

Polish code-breakers arrested/imprisoned

September

Rejewski, Zygalski and others at Felden

Langer and Ciężki at Schloss Eisenberg, Palluth and others at Sachsenhausen

1944

5 January

Bertrand arrested

7 March

Langer and Ciężki interrogated

6 June

Invasion of France by Britain and America

August–September

Warsaw Uprising

1945

30 April

End of World War Two in Europe

10 May

Langer and Ciężki liberated to Scotland

INTRODUCTION

The most significant problem for British military and naval intelligence at the beginning of World War Two, was to understand German communications that had been encrypted on the Enigma cipher machine. During the course of the Great War, code-breaking had given the British an edge, notably in the war at sea, but also on the diplomatic front, accelerating the arrival of the point at which the United States became involved in that conflict. Twenty years on, the use of mechanisation to conceal secret communications threatened to deprive the Allies of this most valuable source of information about the Nazis’ plans.

Nowadays, we know that the British were not daunted by the problem. They had set up a secret establishment, somewhere between London and Birmingham, specifically dedicated to unravelling the modern encipherment techniques being deployed by Germany (and others). Early in the war, a solution to the Enigma machine was found. German Air Force signals could be read from mid 1940, and signals from their navy could be read from 1941. Thereafter, with some ups and downs, a steady stream of decrypted signals began to flow towards the British authorities. In time, the stream became a flood, enabling the Allies to obtain a full appreciation of German military and naval plans in many theatres and enhancing their commanders’ ability to take wise and well-informed battlefield decisions. The success of Bletchley Park is now rooted in the public imagination as an example of triumph in adversity, a showcase of brains excelling over brawn, the cradle of a world-changing technology. Bletchley Park has much to be proud of.

Yet, somewhere in this story, something got lost. In truth, Britain’s code-breakers had made no progress against the military version of the Enigma machine before 1940. How were they able to bring about such a rapid and effective transformation of their fortune?

The missing piece is the contribution of the Polish code-breakers, who had been working on the problem for over ten years before the war and who shared their knowledge in a crucial meeting near Warsaw just six weeks before the outbreak of hostilities. In the estimation of those who were there at the time, what the British learned at that meeting advanced their research programme by a year. And what a year it was. Imagine a counterfactual history in which the British had not been able to decipher Enigma messages during the Battle of Britain, the naval war in the Mediterranean, the early years of the Battle of the Atlantic, or the campaign in the Western Desert. Such a scenario is frightening, as it would be a history that depicts not just a longer, drawn-out war but potentially one with a quite different outcome. In this light, the Polish contribution to the reading of Enigma-coded communications deserves to be better understood.

The July 1939 meeting near Warsaw is itself a major mystery: why did the Poles suddenly hand over all their priceless secrets? Again, there is a missing piece. That meeting was the culmination of a relationship built slowly over many years, not by the British, but by the French. Without the French, the Polish code-breakers would not have been as rapid with their breakthroughs and their efforts might even have been thwarted. Without the French, the British attack on Enigma at Bletchley Park could have been stillborn or significantly delayed. The contribution of the French, like that of the Poles, ought to be better known. The Enigma endeavour was, then, an international collaboration by three countries. For the greater security of the joint enterprise, the code-breakers labelled themselves X, Y and Z for the French, English and Polish centres respectively.

To tell the story of X, Y and Z was the original mission of this book. But this book is not principally about code-breaking techniques or international politics. As I uncovered more of the story, the Polish code-breakers themselves, and their French counterparts, began to take charge of the narrative. This book is, therefore, about those people, and its purpose is to re-establish them in the record where they belong.

Bringing the X-Y-Z story to life has had its own subplots. One, almost worthy of a book in its own right, is the tale of the source material. World War Two had some unexpected results: French records were captured by the Germans and, when Berlin was occupied by the USSR, ended up in Moscow. Much of this material was returned (with Soviet annotations) to France in 1994 and 2000. Many Polish records were dispersed with exiled citizens, ending up in London in various collections. Some remain in Moscow and some are actually where you might expect, in Warsaw. German records were captured by the Americans and the British, finding their way to the US and UK national archives. Some original parts of the record have disappeared, leaving the researcher to rely on shadows of original telegrams, surviving in the form of intercepted, decrypted and translated copies, which turn up in unexpected places. A bizarre example is the large collection of Polish telegrams, in German, in the Foreign Office TICOM archive in Berlin, comprising documents seized in Germany by the ‘Target Intelligence Committee’ at the end of World War Two: these, the fruits of success of the German signals intelligence service, which monitored and decoded the Poles’ radio communications, were thrown into a lake in 1945, dredged out by the British, kept in the UK for decades, and returned to Berlin in the 1990s. The Polish-language originals have long disappeared.

Most of the material relating to X, Y and Z has been declassified. Perhaps the most significant new collection is the archive of an individual who plays a critical part in this story and whose perilous career was spent in France, working for that country’s various intelligence systems. Gustave Bertrand’s archives were made available in mid 2016 after declassification by the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure in France. This collection comprises a long report by Bertrand, together with over 200 supporting files, almost all containing original documentation. Alas, the first ninety-nine supporting files (of a total of 304) are missing, but those which remain bring a wealth of colour and light to the events in the years before the disbandment of Bertrand’s Franco-Polish code-breaking operation in 1942.

Looking at documents is part of the process of discovery; equally important is hearing from those involved. The families of the code-breakers have embraced my project with great enthusiasm, and I have been overwhelmed by the welcome, support and information given by the families of Maksymilian Ciężki, Antoni Palluth, Marian Rejewski, Wiktor Michałowski and Henryk Zygalski. Anna Zygalska-Cannon gave me privileged access to her archive of letters and Henryk’s amazing collection of photographs; she deserves my very special thanks. Especially important to me was the long interview given to me by Jerzy Palluth in January 2017. A man of great courage and intellect – an intellect well spiced with energy and wit – his own life story is every bit as fascinating as that of his code-breaker father. It was a blow to learn of Jerzy’s death only a few weeks after we spoke, not least because his parting words to me were ‘When you next come, I can tell you all about how we resisted the communists during the Cold War.’ I am privileged to have heard at least the first part of his story, and profoundly grateful.

Many others have helped bring this book into being. Katie Beard, Anna Biała, Sébastien Chevereau, Barbara Ciężka, Tony Comer, Prof. Nicolas Courtois, Dorian Dallongeville, Anne Debal-Morche, Georgina Donaldson, John Gallehawk, Dr Marek Grajek, Dr Magdalena Jaroszewska, Prof. Jerzy Jaworski, Dr Zdzisław Kapera, Herbert Karbach, Dr Iwona Korga, Katarzyna Krause, Michal Kubasiewicz, Dariusz Łaska, Stephen Liscoe, Beata Majchrowska, Eva Maresch, Aleksander Markiewicz, Jerry McCarthy, Piotr Michałowski, Prof. David Munro, Lauren Newby, Steve Ovens, Jerzy Palluth, Laura Perehinec, Geoffrey Pidgeon, Halina Piechocka-Lipca, Alicja Rakowska, Katie Read, Ginny Reid, Guy Revell, Jeremy Reynolds, Jeremy Russell, Dr Arkady Rzegocki, Sir John Scarlett, Agnieszka Skolimowska, Eric van Slander, Michael Smith, Anna Stefanicka, Rene Stein, Prof. Michael Stephens, Dr Andrzej Suchcitz, Dr Janina Sylwestrzak, Dr Olga Topol, General Włodzimierz Usarek, Alicja Whiteside, Nicolas Wuest-Famôse and Anna Zygalska-Cannon will all know what contributions they have made and I pay them sincere tribute. My family has also borne with admirable restraint the consequences arising from the process of my writing another book. I have had unfailing help and support from the staffs of the National Archives at Kew; the archive of the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London; the Józef Piłsudski Institute in London (and its sister organisation in New York); the Service Historique de la Défense in Vincennes; the National Archives and Research Administration at College Park, MD; the Center for Cryptologic History at Fort Meade, MD; and the Politisches Archiv of the Auswärtiges Amt in Berlin. I also drew extensively on the commendable blog of Christos Triantafyllopoulos (Christos military and intelligence corner) which not only has valuable and well-researched commentary, but also useful links to source material.

I cannot sufficiently explain how much I have depended on the inestimable assistance of Dr Janka Skrzypek, who has been at my side as research colleague and translator since the first days. For anyone to try to tell this story without drawing on the Polish-language resources would destroy it at the outset: Janka’s participation in the project has enabled me to draw on that essential material. She has provided me with translations of over a hundred documents, some very long, and researched and sifted through many thousands of others to help focus our efforts. She spent several days on my behalf in the Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe (Polish Military Archive) in Rembertów as well as helping me in the Sikorski and Piłsudski Institutes in London. The work has been puzzling, time-consuming, and often tedious, though I hope with some flashes of interest and enjoyment at times. I am extremely grateful to Janka for all the help, guidance and support she has provided over the last two years: without her this book would not have been credible; indeed it would not have been possible.

Finally, a note on style, place names, pronunciations and so forth. Place names have changed since the 1930s and the convention followed here (except where there is an English name, such as Warsaw) is to use the contemporary name with, where necessary, the current name shown in brackets the first time the place is mentioned (for example: Lwów (Lviv)). Pronunciation of Polish names can be troublesome for English speakers, but unless you are reading aloud the correct pronunciation probably doesn’t matter, while worrying about it can get in the way of the narrative. Some phonetic guidance is given in the Dramatis Personae. Spellings in quoted passages appear as they do in the original, except where the passage has been translated, in which case the spelling of names has been corrected. The intrusive word sic has thus been avoided except to clarify a couple of endnotes. Translations were done by me where the source text was in French or German and by Janka Skrzypek where it was in Polish. Errors of all descriptions are, however, mine. I hope there are few enough of them to make this story enjoyable and much better known.

Dermot Turing

St Albans, UK

April 2018

1

NULLE PART

Quant à l’action, qui va commencer, elle se passe en Pologne, c’est-à-dire Nulle Part.

[As for the action about to begin, it takes place in Poland, that is, No Place.]

Alfred Jarry, Ubu Roi (1896)

November 1918 was a good month for Maksymilian Ciężki. Revolution and disorder had broken out everywhere across the German Empire. The bumptious Kaiser had abdicated and sneaked off to the Netherlands. And the leaders of the Imperial Army had been made to sign an Armistice in a railway carriage somewhere in France. A soldier in the Imperial Army ought, perhaps, not to have been gleeful at these developments, but Maksymilian Ciężki was not an ordinary German soldier.

In the eastern provinces of the Empire most of the population were not German, did not want to speak German, and certainly did not want to be ruled by Germans. Since the previous year, some of them had been making plans, and Ciężki was among them. Maksymilian Ciężki was a member of the Boy Scouts before he was called up to serve on the Western Front, but being in the Boy Scouts in the so-called Grand Duchy of Posen didn’t mean tying knots, making camp-fires and helping old ladies across the road. The ‘Scouts’ were a front for the paramilitary wing of the Polish independence movement – the POWZP, or Polish Military Organisation of the Prussian Partition. The ‘Partition’ – the very idea that Poland was divided amongst its imperial neighbours – was offensive to all Poles.

For Ciężki it might have been a good thing that he had been invalided home in February 1918. Either at Rheims or Soissons a mine blew up and half-buried him. Some sort of filth in the air got into his lungs and started an infection. Anyhow, it meant that he could spend some more time with the ‘Scouts’, organising, recruiting and stockpiling weapons; and once he’d recovered, he was spared the front, instead being sent off for training in wireless communications. From then on, the mysteries of radio provided intellectual sustenance, but a dangerous, secret ambition – nothing less than the independence of Poland – possessed his soul. Now, with disruption and chaos breaking out across Germany, was the time for action. Polish leaders had taken control in Warsaw; civil government in the ‘Prussian Partition’ could not go on without the support of local, Polish, people. The Polish People’s Guard was needed to keep order in Posen, or, to call it by its non-German name, Poznań, and Maksymilian Ciężki found himself elected to the local Soldiers’ Council. Perhaps it was the beginning of the end of German rule in the Prussian Partition.

The Prussian Partition was a dark spectre from history; and history, in Poland, has a baneful tendency to repeat itself. On the horizon in 1918 was a post-war peace conference, and the last one of those had not gone well for Poland. Following the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte, the Congress of Vienna had convened in November 1814. The then British Foreign Secretary, Lord Castlereagh, believed he had an answer to the ‘Polish Question’: the re-establishment of the Kingdom of Poland. On the other side of the table, Russia was interested in the attractive towns of Cracow and Thorn (Toruń), even though these were deep in what were the Austrian and Prussian zones of influence (and had nothing whatever to do with the defeated French). Tsar Alexander I, however, was a reasonable man. Instead of insisting on Cracow and Thorn, he would settle for being King of Poland. Castlereagh should be happy with that. The British minister had been saying he wanted to re-establish Poland. So all would be well.

As it turned out, the Kingdom of Poland did not cover much ‘Polish’ territory, since swathes of the old Polish lands remained within the territories ruled by Austria and Prussia, or within the Russian Empire beyond the boundary of the kingdom. Nor did the kingdom have a great deal of autonomy. In 1830 and again in 1863, there were rebellions against the Russian-inspired government, and after the second one, the new Tsar, Alexander II, had experienced enough nationalist discontent. Polish institutions were closed down in the kingdom and governmental activity in the Polish language was phased out. The Tsar ‘relinquished his duties’ as King of Poland; what this meant was that the kingdom was annexed to Russia and by 1874 Poland had ceased to exist. Poland was, according to a contemporary satirical French playwright, ‘No Place’.

Poland might have stayed unrecognised but for the man with the moustache. Certainly, in 1918, moustaches were in fashion, but this moustache was world-famous. It hung in festoons, in theatrical exuberance, in defiant luxury. It was a symbol, it defined the movement for liberation, it identified the man who wore it for those who had only heard him on the wireless and never seen him in the flesh; and it also served a practical purpose – to conceal the gap left after the teeth behind the moustache had been knocked out with a rifle butt in a Tsarist prison in Siberia in 1887.

In a country divided and ruled by three empires there were few opportunities to nurture leaders of a new republic. But one stood out: implacably hostile to Russia, a left-wing activist, and a constant advocate for Poland to regain her independence, by force if needs be. The moustache belonged to that man. He was Józef Piłsudski, and in 1918 he was in a German prison in Magdeburg. But his custodians knew they had a head-of-state-in-waiting and they had no pretensions to govern in Warsaw, where the Russians had been in control for over a hundred years. It was just a matter of working out how to win Piłsudski and a potentially independent Poland over to their side, rather than have it become an Allied puppet. So no one was surprised when, on 8 November 1918, Piłsudski was told he was free to go and a special train was laid on to take him to Warsaw, where he found ‘power lying in the streets’. Within days, and without bloodshed, Piłsudski had manoeuvred himself into a position of control in a new democratic system. The Republic of Poland was born.

But not in what the Poles called Wielkopolska (Greater Poland), that place which the Germans had bundled up into provinces such as the Grand Duchy of Posen, the homeland of Maksymilian Ciężki. Despite its name and the importance of the region, Wielkopolska was at risk of being left out of the new Polish state. Power-sharing with the Germans wasn’t working. The atmosphere was tense, the Germans’ grip was weakening and the province was preparing for a change. All that remained was to give the signal.

On 27 December 1918 there was a VIP visit and a speech in the centre of Poznań. The visitor and speaker was Ignacy Paderewski, world-renowned pianist and advocate of Polish rights. What he said was not important: his audience fully understood the sub-text, and on the next day the Wielkopolska insurgency began. Ciężki’s unit took over the railway station in Poznań. Their next assignment was to take control of Wronki, a nearby town. That was achieved without difficulty or bloodshed, but the revolution was not going so well elsewhere. The Germans had started to fight back. And just at the point when Wielkopolska needed every fighting man, Ciężki was struck down by his pulmonary problems.

Frustrated and inert, Ciężki languished on the sick list, until he thought of his signals experience. To the north of the old town at Poznań, in the early part of the nineteenth century, the Prussians had built a major fortification. The inhabitants of the two villages there had been cleared out, though their history of wine-growing was recognised in the official name by which the new fort was known, even if the locals called it the Citadel. By 1903, Fort Winiary had been modernised with the addition of a telegraph station and now it was in Polish hands. On 2 April 1919, Maksymilian Ciężki joined the Poznań radio unit at the Citadel.1

At the Citadel, Maksymilian Ciężki met another technician who was still in his teens. Antoni Palluth was just out of school and was one of those young men who wanted to seize his country’s destiny for himself – in other words, to throw the Germans out of their country. But for Palluth there was more to being involved in the uprising than national pride. His work was just where his interests and aptitude lay.

Antoni Palluth could pull magic from the air. There was something extraordinary about wireless telegraphy. Invisible, inaudible, undetectable, the air was full of ghostly messages. Yet with modern equipment it was possible to get the air to disclose its secrets: out from the crumble of static it was possible to coax the rhythm of Morse. Sometimes the signal wavelength wandered about and sometimes the machine played up. And when the weather was bad, the chase was hard. But Palluth tended his machine and the machine responded to Palluth’s talent. Antoni Palluth was a first-rate radio engineer.

Palluth and Ciężki were not stationed together for long, but their encounter was a moment of enormous consequence. For these two young men embodied the new, technically focused country that Poland would become. They were the radio men. The comradeship between Ciężki and Palluth would last twenty-five years as they proved themselves capable of being at the forefront of what would become an international effort to break the German Enigma ciphers. For the moment, however, this collaboration was on hold. Palluth was called away to serve in the north of Wielkopolska in mid May and Ciężki was sent on another course later in the year.

Meanwhile, the post-war settlement of Poland needed to be completed, to avoid a re-run of 1814. In the aftermath of ranging armies, with a ravaged economy, thousands of dead, there was a peace conference. Again, as in 1814, the helpful British were suggesting new boundaries, talking airily about the re-establishment of a vigorous, independent Polish state. This time, however, in part thanks to their own tough fighters, the Poles had actually been invited to the party. Indeed, the French were keen to have them there. From the French perspective, the principal aim of the post-war settlement was to contain the Germans. Settling the borders between Germany and Poland was crucial. But it wasn’t just the French who were very positive about a Polish state. President Wilson’s basis for peace, his famous Fourteen Points, included, as Point Thirteen, the following:

An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

This was all very splendid. It provided fuel, of course, for the energetic conversation in the cigar-smoke-filled conference rooms of Paris. But Wilson’s Point Thirteen was not much more than an aspirational statement. The shape of the western frontier of Poland was going to look, on paper, roughly like it had until the late eighteenth century. But in the late eighteenth century, Germany did not exist as a state. For the Germans, the border ought to have been where it was in 1914, when Poland did not exist as a state. What about the chunks of eastern Germany, now reverting to being western Poland, which had been settled over many decades by Germans? At whose expense was the ‘access to the sea’ to be provided? And who were the underwriters of the international covenant of guarantee?

The newly re-established Poland thus had everything to worry about from its still-powerful German neighbour, whose troops were still in occupation of much of the country. Unfortunately, the Poles clearly didn’t understand the purpose of the conference. The conference wasn’t about clearing the Germans out of Poland, or about the viability and future prosperity of Poland. It was about the borders of Germany. And as far as the Allies were concerned, that consideration alone should settle the Polish question.

Except that ‘both Russia and Poland in February 1919 were states in their infancy, the one sixteen months old the other only four months old. Both were chronically insecure, gasping for life and given to screaming.’2 Neither of these countries was waiting to be told by the Great Powers at Versailles about decisions that had been ordained for their own good. They – or, more precisely, the Soviet Union – were going to settle the business themselves.

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, alias Lenin, was the man behind the Soviet plan for Poland. ‘If Poland had become Soviet, if the Warsaw workers had received from Russia the help they expected and welcomed, the Versailles Treaty would have been shattered, and the entire international system built up by the victors would have been destroyed.’ This fantasy manifested itself as a secret plan called ‘Target Vistula’, named after the river running through the centre of Poland: a cover-name which rather gave the game away, even though the Bolsheviks claimed their operation was nothing more than the defence of borders.

The Polish-Soviet War began with the Cavalry Army of Semyon Budyonny pushing Polish forces out of the Ukraine. Then, on 5 July 1920, the Red Army began an offensive in the north-east of Poland under the leadership of Mikhail Tukhachevsky, already a general at the advanced age of 27. ‘Over the corpse of White Poland lies the road to worldwide conflagration’, ran Tukhachevsky’s stirring order of the day. The advance was rapid and spectacular. The Third Cavalry Corps – the fearsome Red Cossacks – rampaged across the north, while Tukhachevsky steadily rumbled towards the west. Russians closed up against the Vistula to the east of Warsaw. Warsaw was going to fall and the Bolsheviks would then be free to march across Europe. Lenin’s dream was going to be fulfilled at last.

In the resort town of Spa in Belgium, famous for its mineral water, the Allies were preparing for another dose of cigar smoke, this time, a conference on the topic of reparations. Unfortunately for the distinguished visitors to the Spa Conference, at the end of the first week of July 1920, what water there was came entirely from the air. The rain drenched the delegates and dampened the mood. If the troublesome business of reparations were not enough, the Poles had now raised a problem that was boiling on the far eastern fringes of Europe, a problem which was self-evidently one of the Poles’ own making. They had grabbed Wilno (Vilnius) and swathes of non-Polish-speaking land around Lwów (Lviv). They were being difficult about Danzig. And now the Poles wanted the Allies to help them stop the Russians.

It occurred to the British that the Russian advance into Poland might be serious: if there were no effective allied intervention to stop the Soviets in their westward drive, ‘the bloody baboonery of Bolshevism’, as Winston Churchill called it, could threaten the democracies of the West. The British had a democratic leader in David Lloyd George, the man who had brought victory to Britain in 1918. But Lloyd George’s authority was crumbling, weakened by his inability to impose order on the conference. To stave off his own political crisis, what Lloyd George needed was to be the man who brought peace to Europe and for that he needed the man from Wola Okrzejska.

Wola Okrzejska is about a 100km south-east of Warsaw, but it is so small it doesn’t feature on many maps. It is, however, a place embedded in the Polish subconscious, for it is the birthplace of Poland’s answer to Sir Walter Scott. Henryk Sienkiewicz was a Nobel prize-winning novelist whose name was known across the world in the first half of the twentieth century: every household had a copy of his novel Quo Vadis, about love and struggle among Christians in Nero’s Rome, which was translated into at least fifty languages and had been made into a movie three times already by 1924. In Poland, Sienkiewicz is probably better known for his patriotic historical novels set in the Polish Commonwealth of the seventeenth century, where dauntless Poles battled for the survival of their country against insurgent Cossacks, unstoppable Swedes and rapacious Muscovites. In 1920, the formidable Red Cossacks galloped freely across Poland, as in the bad old days described by Sienkiewicz, while the Red Army was marching inexorably on Warsaw.

It was, therefore, entirely apposite that in this political crisis Lloyd George should look for inspiration to another man from Wola Okrzejska. The man had been born in 1888 in a country house which his grandfather had bought from an uncle of Henryk Sienkiewicz. His name was, at one point, Ludwik Niemirowski, under which he had a glittering academic career, studying at universities in Lwów, Lausanne, London and Oxford. In 1907, now called Lewis Namier, he settled in Britain. When war broke out, Oxonian friends ‘plucked him out of the British Army (where his poor eyesight and guttural accent seemed likely to get him shot by his own side if not by the Germans) and placed him in the intelligence service at the Foreign Office.’3 Later Namier participated in the Versailles treaty discussions. In 1920, he was the established Foreign Office expert on Polish cartography. It is the time-honoured role of the British at international peace conferences to propose lines on maps to deal with disputatious peoples and Namier had been busy with his pencil. The British proposed the boundary between the Russians and the Poles, one that they thought would put to bed the annoying problem of Poland’s eastern boundary and bring the war to a rapid end. The line was named after Namier’s boss, Lloyd George’s foreign secretary Lord Curzon. Given that he had nothing to do with it, it’s unfortunate that Lord Curzon is the man whose name this border bears and it is ironic, too, that the boundary was actually the creature of an expatriate Pole.

The Curzon Line runs roughly north and south along conveniently placed rivers, at least to the north. To the south the rivers behaved in a less convenient way and there was controversy about whether the line would go to the east of Lwów (thus placing Polish-speaking Lwów and its non-Polish surroundings in Poland) or to the west of Przemyśl (so giving both cities to the Ukraine, or to be more exact, the USSR). Both choices were bad: huge tracts of the country would be given up, whichever option was accepted. Under diplomatic pressure from the British, and with the news from the front getting worse every day, the Polish delegation caved in. The less bad version of the Curzon Line, with Lwów on the Polish side, would just about do. The Polish state was not yet two years old and already many hundreds of square miles were being ceded to the Russians. It was partition all over again. If the country was going to survive at all, the state needed something extraordinary, a modern miracle.

Lieutenant Stanisław Sroka worked as a radio man in Warsaw, handling the boring business of assessing intercepted Russian radio traffic, rather than finding glory at the front. It was tedious and depressing, but even in times of war, life goes on. Lieutenant Sroka’s sister was going to get married and as he was to give away the bride, the lieutenant asked for a leave of absence to carry out this important duty. The Russians, inconsiderately, did not order a ceasefire or a cessation of movement during the nuptials, so it was necessary for someone to cover the good lieutenant’s dull duties in military intelligence while the vodka was drunk and the dancing went on. There must have been a lot of vodka, because the officer whom Lieutenant Sroka chose to fill in for him was asked to cover for two weeks. His choice was another army lieutenant, but unlike Sroka, the replacement was a man who had read Edgar Allan Poe’s short story The Gold Bug. In The Gold Bug a simple cipher led the hero to buried treasure: fabulous stuff and something which captured the imagination. Jan Kowalewski, the replacement lieutenant, put his reading to good use. In those two weeks, he turned radio interception into a different sort of treasure which captured the imagination of the most senior members of the Polish General Staff.

For, having received a bundle of intercepted messages which were in some sort of numerical cipher, Kowalewski was not content with analysing the call signs and potential evidence of troop movements: he wanted to know what the messages were actually about. He determined to attack this puzzle and soon found that the cipher was a simple enough bigram substitution system with an overlaid twelve-digit key. And the messages were certainly worth reading.

What the messages revealed was not just what the Reds were thinking, but their appreciation of the Whites. The threat to Poland was not just from the Bolsheviks: if the Russian imperialists regained power, they would want to get their old empire back, right up to the German border. But Kowalewski’s decrypts showed that General Deniikin, the White commander, was being threatened in his rear by the Reds. Being able to see both sides of the Russian civil war amazed the Polish chief-of-staff, General Rozwadowski. The gift was an eagle’s-eye view of the entire strategic situation. It wasn’t good news, but it was just what General Rozwadowski needed to know. From now on, monitoring and decryption were a priority.

Jan Kowalewski looked like something of a bear, with his imposing physique, but people who got to know him valued him for his sense of humour and his extraordinary, intuitive mind. By putting Kowalewski in charge of Polish decryption a crucial step was taken that would lead to Poland becoming world leaders in the art of code-breaking. For Kowalewski’s first request was to ask for all volunteers who were mathematics professors to be assigned to his team. Before Kowalewski, code-breakers were supposed to be linguists and psychologists. But Kowalewski was an engineer and he was redesigning the profession of cryptology.

The new, scientific approach soon showed its power. Over three days in early July 1920, crucial messages revealed new Russian operational orders given to coordinate the operations of Budyonny with the other Red Army forces invading Poland:

An order for the Army of the South-Western Front … The 14th army, taking into account the tasks of the Cavalry Army, will break the resistance of the enemy on the line of the River Zenic and will use the full force of its assault team when carrying out a decisive offensive in the general direction of Tarnopol-Przemysl-Gorodok …

[signed] The Commander of the South-Western Front YEGOROV

Member of the front’s Revolutionary Council STALIN

Chief of Staff of the South-Western Front PIETIN

24/VII-1920

Deciphered/checked against original: Kowalewski4

These orders spelt out a new offensive:

The enemy himself informed our headquarters precisely of his moral and material state, his strengths and losses, his movement, of victories attained and defeats sustained, of his intentions and orders, his headquarters’ stopping points, of the deployments of his divisions, brigades and regiments, etc … We were able to follow the whole operation of Budyonny’s Horse Army in the second half of August 1920 with simply incredible precision … On 19 August we monitored, and on 20 August read, an entire operational order from Tukhachevsky to Budyonny, in which Tukhachevsky states the tasks of all his armies.5

The intelligence went straight to the Chief of Staff and some even into the hands of the Commander-in-Chief, Józef Piłsudski himself.

It just got better and better. The radio men intercepted messages that told of the Bolsheviks’ order of battle, the dispositions of their forces, and even details of new ciphers they were going to use. They could overhear the arguments about the gap between Tukhachevsky’s army and Budyonny’s. The Red Army under Tukhachevsky was entirely stretched out: it might make sense for the Russians if they were going to encircle Warsaw, but it made them vulnerable, providing Piłsudski could move his troops into position. Piłsudski raced his troops through the gap, leaving Warsaw wide open, so he could encircle Tukhachevsky from the rear in a classic Napoleonic manoeuvre. Badly outnumbered, Piłsudski was taking an enormous gamble based on the intelligence supplied by Kowalewski.

On 12 August 1920, Kowalewski’s unit picked up a message several pages long. It was obviously important, not just due to its length, but also because it was in a new cipher. Kowalewski’s team were at the top of their game: it took them just an hour to work out the new system and to decipher enough of the message to get its gist. The decisive attack on Warsaw was due on 14 August and there was only just time to react. Being strung out over hundreds of miles, communication between the Russian units was dependent on radio. The crucial goal was to keep Tukhachevsky where he was while Piłsudski completed his own manoeuvres. To shift the odds, if only fractionally, Piłsudski ordered that the Russian radio communications be jammed. It would cut off the supply of intelligence but cause delay and confusion among the enemy, and a couple of extra days was all that Piłsudski needed.6

Miracle on the Vistula. A Russian telegram, countersigned by Stalin, and decoded by Jan Kowalewski, during the Russo-Polish War of 1920. (Instytut Piłsudskiego w Ameryce – Piłsudski Institute of America)

The troops were moved. Spearheaded by General Władysław Sikorski, the great roll-up of Tukhachevsky’s army began. The surrounders were themselves exposed to locally superior numbers, which allowed them to be defeated in detail. A hundred thousand prisoners were taken by the Poles; in fear, the Red Cossacks galloped away into East Prussia, where they were interned by the Germans. And Tukhachevsky escaped with the remnants of his army back to Russia to face a grilling from Trotsky and Lenin.

In Poland, these events were called the Miracle on the Vistula. In August 1914, three very different forms of government had existed on Polish territory. There were six currencies, four legal codes, two railway gauges, and countless languages (even if Russian and German were the only ‘official’ ones). Now, with the country unified and at peace, the nation could become a state and fly its own flag once more: a crowned eagle, with an exuberant tail, on a red and white field. Radio and cryptology had put Poland back on the map. The vital role of Kowalewski’s decryption team had been understood by the authorities and they, perhaps more than any other government in the world, appreciated the importance of supporting a modern approach to the profession. Thanks to the Polish radio men, Europe would remain free of the Bolshevik menace. For the time being.

2

ENTER THE KING

SHEPHERD: Sir, there lies such secrets in this fardel and box which none must know but the king.

William Shakespeare

The Winter’s Tale, Act 4, scene 3

Jan Kowalewski was a little older than Maksymilian Ciężki, so his impact on Poland’s existential struggle of 1920 had been greater. Ciężki himself had been in Poznań, still in radio. His friend Antoni Palluth had been closer to the action, in the front line for much of the conflict, but also in radio. After the war, Kowalewski, the man at the top, was in demand for many roles, political and diplomatic as well as those based in the shadowy world of intelligence. In 1922, he was seconded to Tokyo to help the Japanese improve their own codes and ciphers, to the irritation of an American code-breaker who then found his attacks on Japanese codes thwarted. It was necessary to find a replacement for Kowalewski as head of signals intelligence. So in 1923 – shortly after Maksymilian Ciężki was assigned to the Radio Intelligence Unit – Kowalewski handed over the reins to an agreeable successor, Franciszek Pokorny. At least Ciężki had been under Kowalewski long enough to be noted by the man whom all the authorities revered. For Ciężki to have his appraisal form marked ‘good’ by Kowalewski was no light matter.1

Following the war, Maksymilian Ciężki had been pursuing a traditional military career. After his father’s death in 1920, although only 21, he’d found himself responsible not just for his own upkeep but also that of eight siblings, five of whom were girls. He needed a stable source of income. For a young man with his record, army life provided a straightforward opportunity for this. Ciężki was commissioned as a lieutenant, completed his interrupted secondary education, and was posted to various places around the country, always specialising in communications. Now, settled into radio intelligence, he could also settle into family life, marrying Bolesława Klepczarek in 1924. That year, Ciężki’s first son, Zdzisław, was born, followed by Zbigniew in 1926 and Henryk in 1929. Life was relaxed. Ciężki could spend his spare time in the garden. He had a good job, working with good colleagues.

Antoni Palluth’s path into radio intelligence was somewhat different. In the Bolshevik war he’d been posted to a radio intelligence unit, where he’d been introduced to traffic analysis and cryptanalysis as skills to add to his existing radio interception abilities. He had been on the reserve list since 1921 and was setting himself up in business. When he had returned to civilian life after his own part in the defence of Warsaw in 1920, Palluth had studied civil engineering at the Technical University in Warsaw. Palluth had not given up his interest in radio with the end of the war. Far from it, he’d become a radio ham, with his own call sign (TPVA), a subscription to a number of radio magazines and a love of sending crackly messages from his house through the ether to his friends. Being an amateur radio-ham was not just good fun. There was money to be made in radio too. The military signals branch of the Polish Army needed long-range short-wave radios; masts; interception equipment; transmitters; amplifiers; you name it. Palluth’s friends Ludomir and Leonard Stanisław Danilewicz (call sign TPAV) were thinking of going professional and their mutual friend Edward Fokczyński had already set up shop making walkie-talkies and radio equipment in a small workshop in the centre of Warsaw.2

In this way, a new business was born. With Palluth and the two Danilewicz brothers providing financial capital and Fokczyński throwing in his premises and existing business goodwill, the new partnership took over a little factory in 43 Nowy Swiat. It was called AVA, by amalgamation of the Palluth and Danilewicz call signs, and the first orders for radio equipment came from the Polish Army’s signals intelligence section. Radios the size of a credit card holder were made for use by Polish agents in foreign territory: AVA technology was miniaturised, sophisticated, and extremely secret.

Yet Antoni Palluth was no ordinary young entrepreneur. He was a paid-up member of military intelligence and his role as factory manager was a cover for a wider range of clandestine activities. Poland’s need to keep a close eye on Russia and Germany had not disappeared with the Treaties of Versailles and Riga: only an optimist would assume that either of those neighbours was comfortable with the new order. Foreign ciphers were every bit as important now as they had been during the war and Antoni Palluth was one of the secret team whose job was to find out what evils lay in the plans of the Germans. In the evenings, an officer would come round to the Palluth household with cryptological problems for Antoni to work on. For, since June 1924, as well as his ostensible day job for as a radio factory manager, he had been working for the Second Department – the intelligence section – of the Polish General Staff, and he held a post in Maksymilian Ciężki’s German section of the Biuro Szyfrów, the cipher bureau.

Despite the help he was getting, Ciężki had a problem. Until 1928, the German section of the cipher bureau had been operating smoothly; indeed, one might say it had been going by the book. The book in question was by General Marcel Givierge, the head of French military cryptanalysis in the Great War, who had done the unthinkable and written up the cryptographic techniques of his era and published them for all to read. The book begins with the simplest form of cipher (in use since Caesar’s time) and details substitution systems, transposition systems, bigram methods, double-key substitutions, book codes and even some mechanical methods for coding. It also covered code-cracking techniques, such as frequency analysis for substitution ciphers, along with methods for finding key lengths. The toughest problems were known to the Poles as Doppelwürfelverfahren, or double dice, and these arose from a hand-based cipher system in current use by the German military. Double dice involved reshuffling the letters of a message according to a predefined scheme – a bit like a giant anagram – and then reshuffling them again using a different scheme. In Givierge’s book the double dice system was laid bare. That didn’t necessarily make it easy to crack: the code-breakers needed to find the two keys to the double-transposition system in order to tease the plain text out and this took sweat, concentration, and plenty of squared paper.

Ciężki’s team could get results against Doppelwürfelverfahren