Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

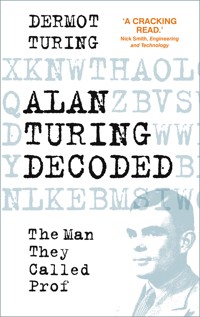

Alan Turing was an extraordinary man who crammed into his 42 years the careers of mathematician, codebreaker, computer scientist and biologist. He is widely regarded as a war hero grossly mistreated by his unappreciative country, and it has become hard to disentangle the real man from the story. Now Dermot Turing has taken a fresh look at the influences on his uncle's life and creativity, and the creation of a legend. He discloses the real character behind the cipher-text, answering questions that help the man emerge from his legacy: how did Alan's childhood experiences influence him? How did his creative ideas evolve? Was he really a solitary genius? What was his wartime work after 1942, and what of the Enigma story? What is the truth about the conviction for gross indecency, and did he commit suicide? In Alan Turing Decoded, Dermot's vibrant and entertaining approach to the life and work of a true genius makes this a fascinating and authoritative read.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 456

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

First published in 2015 as ‘Prof: Alan Turing Decoded’

This revised and updated edition first published in 2021

© Dermot Turing, 2015, 2016, 2021

The right of Dermot Turing to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9924 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Introduction

1 Unreliable Ancestors

2 Dismal Childhoods

3 Direction of Travel

4 Kingsman

5 Machinery of Logic

6 Prof

7 Looking Glass War

8 Lousy Computer

9 Taking Shape

10 Machinery of Justice

11 Unseen Worlds

Epilogue: Alan Turing Decoded

Notes

INTRODUCTION

Alan Turing is now a household name, and in Britain he is a national hero. There are several biographies, a handful of documentaries, one Hollywood feature film, countless articles, plays, poems, statues and other tributes, and a blue plaque in almost every town where he lived or worked. One place which has no blue plaque is Bletchley Park, but there is an entire museum exhibition devoted to him there.

We all have our personal image of Alan Turing, and it is easy to imagine him as a solitary, asocial genius who periodically presented the world with stunning new ideas, which sprang unaided and fully formed from his brain. The secrecy which surrounded the story of Bletchley Park after World War Two may in part be responsible for the commonly held view of Alan Turing. For many years the codebreakers were permitted only to discuss the goings-on there in general, anecdotal terms, without revealing any of the technicalities of their work. So the easiest things to discuss were the personalities, and this made good copy: eccentric boffins busted the Nazi machine. Alan may have been among the more eccentric, but this now outdated approach to studying Bletchley’s achievement belittles the organisation which became GCHQ, and distracts attention from the ideas which Alan, among others, regarded as far more important than curious behaviour.

I am sceptical about that solitary genius picture of Alan Turing. It doesn’t fit well with what little was said about him at home during my childhood, and it doesn’t fit with the personal recollections of those work colleagues of his with whom I have had opportunities, over the years, to talk. A man called ‘Prof’ by his friends – who knew he wasn’t a professor and so were teasing him, gently – wasn’t shut away from intellectual or social interaction. Who, in fact, was Alan Turing, and where did his ideas come from?

Of course, these questions have been explored before and from a variety of angles. Yet some of the people who influenced and mentored Alan have perhaps received less attention than their due: notably, M.H.A. (Max) Newman, who was not only an intellectual equal but also provided a compass to help steer Alan’s career and a social anchorage in a less rarefied family setting. There is a temptation to portray Alan as a victim of his childhood and schooling; I don’t think that is accurate or fair. There is also a tendency to zoom in on the last tragic years of his life, to view the whole of his existence through that Shakespearian lens, and then to define Alan Turing by reference to his sexuality or suicide. Again, I think that is an error. To complement my personal viewpoint I have had access to new documents and sources which were not available even to Alan’s most recent biographer. Moreover, a wealth of material has been made available to me in the form of first-hand recollections of those who lived and worked alongside Alan; I wanted to allow those voices to be heard again.

I have been constantly surprised and delighted by the enthusiasm with which each enquiry I made relating to this project was received. So many people I contacted were willing to volunteer additional information and suggestions, going far beyond any ordinary duty in the help offered to me. I had the privilege of interviewing Donald Bayley and Bernard Richards who were able to share their personal recollections with me and answer my foolish questions – a big thank you for letting me intrude into their lives. I was also allowed to preview documents scheduled for release to The National Archives, not available to previous biographers, and for that I am grateful to the Director of GCHQ. I should also like to acknowledge in particular the varied contributions of Shaun Armstrong, Jennifer Beamish, Claire Butterfield, Tony Comer, Barry Cooper, Daniela Derbyshire, Helen Devery, Juliet Floyd, Rainer Glaschick, Joel Greenberg, Sue Gregory, Kelsey Griffin, John Harper, David Hartley, Rachel Hassall, Cassandra Hatton, Kerry Howard, Paul Kellar, Miriam Lewis, Barbara Maher, Gillian Mason, Patricia McGuire, Christopher Morcom QC, Charlotte Mozley, Harriet Nowell-Smith, Brian Oakley, James Peters, Brian Randell, Hélène Rasse, David Ridgway, Rachel Roberts, Isobel Robinson, Sir John Scarlett, Lindsay Sedgley, Susan Swalwell, Turings past and present, Cate Watson and Abbie Wood. Nor would I have been able to succeed without the friendly and useful assistance from the staffs of the British Library, Chester Records Office and various local libraries in Cheshire, The National Archives, and the Science Museum; and, in the US, the Library of Congress, the Mudd Manuscript Library at Princeton and the National Archives Records Administration. In none of these places was anyone anything other than welcoming, helpful and informative.

However, I have to pay tribute in particular to Andrew Hodges’s masterly biography Alan Turing: The Enigma. I bought my copy in February 1984 as soon as it came out. It is a big book and it covers the ground with majesty as well as rigour. Nothing – certainly not what follows between these covers – can possibly stand up to it. It has been my constant reference source. It has stood thirty years without need of fundamental correction. Sure, there are materials available now which were not open to Andrew when he did his research, but these colour in points of detail, and affirm his conclusions where there was limited evidence available to him. My perspective is of course different, otherwise this book would not have been worth writing, but I commend it to the reader whose appetite I have managed to stimulate. Errors are to be blamed on me, not others.

Dermot TuringSt Albans, UK

1

UNRELIABLE ANCESTORS

It is May 1790. Major-General Medows, the officer commanding Fort St George (later called Madras), has been in office for three months. His governing council is not behaving in the manner which suits him, and the war with Tipu Sultan – stirred up by the French, of course, notwithstanding their own domestic upheavals – has reached a critical phase. The General needs to go on campaign, and he needs to leave a sound man, or ideally some sound men, in charge of the council in his absence. There is nothing for it. John Turing, who was put onto the council by the General in February, and has shown he can be depended upon, will take over as Acting President.

John Turing has a long and respectable history in Fort St George. Indeed, the Turing family has been a pillar of the community since anyone can remember. Dr Robert Turing arrived in Fort St George in 1729 and was a surgeon in the district until the early 1760s; he even treated Sir Robert Clive in 1753. Dr Robert Turing’s daughter Mary is married to John – they are second cousins. Mary knows everybody: ‘by the marriages of her family and relatives [she is] connected with half the settlement’.1 Dr Turing’s house is being talked about, now that war has flared up again: in the Siege of Madras in 1758 the French approached the town through his garden, of all things. Mary isn’t going to let the citizens of Fort St George forget this. Another Robert Turing, another cousin, is serving in the Madras Army; in full time he will retire grandly to Banff Castle in Scotland and pick up the family baronetcy. John and Mary’s son William is serving as Paymaster too, and in 1813 he will be killed in Spain at the battle of Vitoria. The Turings are an Empire family, sound but not famous.

In 1790 the Turings are also reading the Madras Courier, which has over the years carried the gossip from home. One scandal concerns another ancestor of Alan Turing, and this particular one is both unsound and infamous. One might expect that the main influences on a child born to Edwardian parents, in the Indian Empire, out of the house and lineage of the Turing family rooted in the Indian Empire, would be from the father’s side. But, while the influence of old-fashioned patriotic service is relevant to Alan’s upbringing and early years, greater direction on his life was given from Alan’s mother’s side, the Stoney family. And of all of Alan Turing’s ancestors, the best-known and most scandalous is Andrew Robinson Bowes, born Andrew Robinson Stoney in 1747.

A close shave in heredity

Thomas Stoney immigrated to Ireland in the 1690s, when William III encouraged Protestants to settle there. His grandson Andrew entered the Army, married Hannah Newton in 1768 for her money, and is said to have ‘locked his wife in a closet that would barely contain her, for three days, in her chemise (some say without it), and fed her with an egg a day’.2 To establish his right to a life interest in Hannah’s fortune after her death, Andrew Stoney had to prove that a child had been born alive; unfortunately all were stillborn, though that did not stop Stoney from ordering the church bells rung in order to rig the evidence. Being nurtured on an egg a day, and required to produce live children notwithstanding, meant Hannah died in 1775. But this merely opened the field for Stoney to try for the biggest fortune in Europe. Mary Eleanor Bowes was worth over a million pounds. Her father’s will obliged any man who married her to take the name of Bowes; when her husband, the Earl of Strathmore, died in 1776 she was in the market. Everyone was after her, and the hot favourite was a Mr George Gray, who had held some office in India under Sir Robert Clive. Indeed, the noble Countess had been carrying on for some time with Mr Gray. Stoney was not going to be put off by any of this. Acting in cahoots with the newspaper editor, an article was run in the Morning Post which alluded offensively to Lady Strathmore. Stoney took it upon himself to defend the Countess’s honour and call out the editor; the two of them staged an encounter at the Adelphi, at which Stoney appeared to have been mortally wounded. The Countess took pity on the one lover who had defended her honour and – a low-risk stratagem, given his imminent demise – agreed to marry him. Four days later, Stoney was carried into St James’s Church, Westminster, where the ceremony took place.

Unfortunately for the Countess, Stoney did not do the considerate thing, and remained obstinately alive. Unfortunately for Stoney, the Countess had already become pregnant by Mr Gray – a state of affairs which, with every passing day, more urgently demanded to be covered up with a marriage to somebody, perhaps anybody – so with all that in mind she had settled all her estate on trust in such a way that it was out of reach of any convenient, or, as the case might be, inconvenient, husband. But Stoney was equal to this challenge. He recovered from his fatal wound with alacrity, assumed the name Bowes, coerced his wife into making a new Deed to revoke her trust settlement, locked her up wherever there was an available closet, felled her trees, sold her estates, gambled away her money, got the wet-nurse pregnant, raped the nursery maid, and told everyone who enquired that the Countess was a little mad. After some years of this treatment she was, with the aid of her lady’s maid, able to escape, and she started legal proceedings in the labyrinthine complexity of the Georgian courts, to have Stoney Bowes bound over to keep the peace, to have the Deed of Revocation annulled, and to obtain the unthinkable: a divorce. As usual Stoney Bowes was unfazed. As insurance against such unwifely behaviour, he had directed the Countess to write a lengthy account of her own wild behaviour, her extramarital affairs, and the true parenthood of her children. The Confessions were brandished in various courtrooms, but they merely served to prolong the litigation and ensure that the case received the maximum attention in the press, such as the Madras Courier. Stoney Bowes was confined to prison – but in those days he could buy (with his wife’s money) the plushest suite and days out on licence, and he had sufficient liberty to sire two children with the daughter of a fellow inmate. In the words of Dr Foot, the surgeon who had patched up Stoney Bowes’s fake wounds after the fake duel back in 1777, Stoney Bowes was ‘cowardly, insidious, hypocritical, tyrannic, mean, violent, selfish, jealous, revengeful, inhuman and savage, without a single countervailing quality’.

How odd, or not, it is that Andrew Robinson Stoney, Thomas Stoney’s eldest son, has not been mentioned on the Stoney family monument? (Author)

Alan Turing was descended from the Stoneys on his mother’s side. John Turing, Alan’s brother, noted thankfully that Stoney Bowes ‘was a collateral, but it was a close shave in heredity’.3 Despite the high risks arising from being nearly descended from Stoney Bowes, it was the Stoney family inheritance which shaped Alan’s ideas and laid the foundation for his breakthroughs in mathematics, engineering and science. Stoney Bowes was the exception: the rest of the Stoneys were not schemers, womanisers, gamblers and deceivers. In fact, by the end of the Victorian era the Stoneys had piled up an immense portfolio of achievements.

The descendants of Stoney Bowes’s two brothers were glittering:

• George Johnstone Stoney FRS (1821–1911). This extraordinary scientist published 75 papers during his career, on subjects including optics, gas theory and cosmic physics. He is probably best known for coining the word ‘electron’ when he was arguing for units of measurement to be based on real physical things – in the case of electricity, the unit of electrical charge which flows when a single chemical bond is ruptured. But to a Victorian eye, one of his most astonishing decisions was to ensure his brainy daughters Edith and Florence were given a head-start in life equal to their brothers.

• Edith Anne Stoney (1869–1938). George Johnstone Stoney’s eldest daughter was sent to Cambridge to study mathematics, where she achieved 17th place in the formidable final exams. After lecturing in physics at three universities and teaching at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, Edith became President of the Association of Science Teachers, and served in the Great War as a radiologist in France, Serbia and Greece, being awarded the Croix de Guerre.

• Florence Ada Stoney OBE (1870–1932). Florence was a consultant radiologist. In addition to her various hospital appointments, like her sister she served in the Great War, notably during the bombardment of Antwerp in 1914, in France, and in London, using her skills to locate foreign bodies embedded in the flesh of the wounded. She was awarded the Admiralty Star as well as becoming an OBE.

• Bindon Blood Stoney FRS (1828–1909). Bindon was George Johnstone Stoney’s brother. He was a railway engineer, wrote a treatise on strains in girders, and reconstructed the port of Dublin to accommodate deep-water ships, which involved inventing a method for placing huge concrete blocks weighing 350 tons apiece. For these and other achievements he is known, without irony, as ‘the father of Irish concrete’.

• George Gerald Stoney FRS (1863–1942). George worked as chief designer in the Steam Turbine Department of Sir Charles Parsons’s company. In this capacity George enjoyed a moment of triumph aboard Turbinia, the experimental steam-turbine yacht part-designed by him. The yacht caused consternation by disobeying all the rules at the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Review in 1897. By weaving in and out of the other craft at 34 knots and outpacing the Admiralty police vessels, it showed that bulky, slow, old-fashioned reciprocating engines were no longer appropriate for the propulsion of dreadnoughts. Later, George became Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the Manchester College of Technology, as well as serving on the panel of the Admiralty Board of Invention and Research.

• Francis Goold Morony Stoney (1837–97). Francis was also an engineer. After a stint in India, working on the Madras Railway, he designed and patented a series of sluices, used in places such as the Manchester Ship Canal, the Rhône, the Clyde, and posthumously the old Aswan Dam.

• Edward Waller Stoney CIE (1844–1931). Edward went to India in 1866 and served as a railway engineer in Madras for many years, becoming Chief Engineer in 1899 and being decorated as a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire in 1904. He wrote numerous technical papers on bridges, flooding and other railway topics, and was a fellow of Madras University. It was in his house in Coonoor, Madras province, that E.W. Stoney’s daughter Ethel Sara lived with her husband Julius Turing.

And this is just to mention those Stoney descendants who carried the name Stoney. In Who Was Who 1929–1940, there are three entries for Stoneys but none for Turings. With this array of Stoney achievements, nothing the undistinguished Turings had done was going to measure up. Since the early days of Empire, the Turings had been soldiers and vicars and merchants; they had been established in England, the Netherlands, and Indonesia as well as India; they had been conventional, upper middle class, impoverished, occasionally snobbish and always unexceptional. It was, however, the Empire that brought the Turings into contact with the Stoneys; although the laws of symmetry suggest that the contact should have come about through the province of Madras, in fact it arose from the state of poverty.

The importance of being poor

According to the parish council website, in 1334 the Vicar of Edwinstowe was convicted of venison trespasses. The vicars holding the living of Edwinstowe in the nineteenth century were more law-abiding, but correspondingly hungry. On 8 October 1879, the incumbent celebrated the birth of a healthy boy, bringing to eight the number of children (not counting the two who died in infancy) that had to be fed and clothed from his stipend. The parish council website also suggests that parishioners had the privilege of letting their pigs root for acorns in Sherwood Forest, but rooting for acorns might be unbecoming for a vicar. So the System was introduced: on Sundays, there was a ‘great spread’ of roast beef or similar; on Mondays, there were leftovers; and on Tuesdays to Saturdays inclusive, there was bread, dripping and cocoa. In 1883, aged only 58, the vicar suffered a stroke and had to resign even this insufficient living, and the family moved to Bedford. Shortly afterwards he died. Julius Mathison Turing, the fifth of the eight children, was ten.

The Turings did not speak of how they managed to ride this terrible storm. The eldest girl, then aged 21 and known to posterity as Aunt Jean, took over the management of the house. Aunt Jean was a formidable character – allegedly the only person of whom Alan Turing’s mother Ethel Sara was truly afraid. Later in life Aunt Jean married (and ruled over) Sir Herbert Trustram Eve, and served as a councillor for 12 years after the Great War, representing the Municipal Reform Party on the London County Council. Her training was in the Turing household of the 1880s. Aunt Jean and the other two eldest children, also girls, also resourceful, earned money through teaching, enough to keep the boys at school: Arthur and Julius at Bedford, and in due course the younger ones Harvey and Alec at Christ’s Hospital in London. Sybil, the girl between Julius and Harvey, went to Cheltenham Ladies’ College, and became a missionary in India when she was old enough to fly the nest; India was the destiny for Arthur and Julius as well. Bedford School was a feeder for the services, military as well as civil, in India, and these were genteel, but more importantly well-paid, occupations. Arthur headed for the remunerative staff corps in the Indian Army, until aged 27 he lost his life fighting for the 36th Sikhs in a skirmish on the North-West Frontier in 1898. Julius was bound for the Indian Civil Service.

The senior generation – Grandpa Stoney and Aunt Jean. (Author)

The legacy of childhood for Julius was a lifelong obsession with accounts. Alan’s brother John wrote:

When I first left school and was articled to a firm of solicitors in London, I was allowed £5 a month for my expenses, including the midday meal, and a separate allowance for clothes. This was not ungenerous but there was one fly in the ointment: I was bidden to submit a monthly balanced account. Great was my father’s chagrin when he discovered that ‘umbrella repairs’ figured in three monthly accounts out of four and that a mistake in casting showed 2/9d in his favour for which I had failed to give him credit! The maddening thing was that I did spend the money in umbrella repairs but, being a Turing, I never thought to add verisimilitude to truth by making it something else.

And again:

On one occasion when we were on holiday in Wales, there arrived a bill from a Harley Street specialist for a consultation to which my mother had taken my brother and myself for advice on our hay-fever. The fee was ten guineas – a large sum in those days. There was considerable dudgeon and my father cried out loudly from the breakfast table that he was ruined. This sticks in my memory as one of the deeper dudgeons.

But, in India, Julius met his match. On completion of his studies at Bedford School, Julius Turing won a scholarship to read history at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. And there he sat the Indian Civil Service exam, passing high in the list. (Julius had to borrow a hundred pounds from a family friend to pay for his passage, his tropical outfit, an English saddle and an Indian pony. The lender asked that Julius insure his life for the amount of the loan and charge it as security. Julius faithfully paid premiums on the policy until his death, when John collected on the policy as his father’s executor. It had never occurred to Julius to discontinue it when the loan was paid off, which he had punctually done within six months.) In India, and having secured his decent salary, Julius was posted to Madras, as befitted a Turing. Madras was also where his future father-in-law was to be found, and E.W. Stoney could outsmart any Turing in the matter of book-keeping. This became apparent as soon as Alan’s parents got married. As was the custom, a red carpet was laid from pavement to porch, which the happy couple trod. John reports:

No sooner was the honeymoon over than my grandfather sent the bill for the carpet to my father. My father deemed it to be part of the wedding expense traditionally at the charge of the bride’s father. My grandfather thought otherwise. After much fuming my father paid the bill but the incident rankled for upwards of forty years.

In later days, Grandpa Stoney would bring to an end any family argument with a statement of ultimate finality: ‘I am off to King & Partridge to alter my will.’ But that is to get ahead of ourselves. Despite the Madras connection, it was entirely a matter of chance that Alan’s parents met, let alone got married. Really, they should not have met at all.

An Irish upbringing

Unlike Julius Turing, Ethel Stoney was born and spent her early childhood in India, where E.W. Stoney was working his way up the Engineering Department of the Madras Railway Company, having been appointed fourth-class engineer in 1866. He married Sarah Crawford, a suitable Irish girl, in 1875; there were four children, of whom Ethel was the third. Expatriate families all have the difficult problem of what to do with the children. In the case of the Stoneys, the answer, they concluded, was to deposit all four with Sarah’s brother William Crawford, who was a bank manager working in County Clare. The Crawfords already had a full house, with six children, two of whom belonged to William’s previous marriage. Late in her life Ethel complained that Aunt Lizzie, William’s wife and thus Ethel’s foster mother, showed her no affection – doubtless the fostering arrangement was a trial for all involved. And the Crawfords were not the Stoneys – respectable, middle class, and wholly lacking in connections to the Bowes family, certainly, but not engineers or fellows of the Royal Society either.

In 1891, when Ethel was ten, the Crawfords moved to Dublin, and after a spell at school there both Ethel and her elder sister Evie were sent to board at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, Evie joining aged 14 in 1892 and Ethel, aged nearly 17, in 1898. This was in the days of the pioneering and dynamic principal Miss Beale, who was offering advanced courses for young women which prepared them for university exams as well as the kind of secondary education more commonly expected of boarding schools. Her philosophy was expressed in 1898 as follows:4

How can girls be prepared for such work as falls to them as heads of great schools, and hospitals, and settlements, as doctors in foreign lands, if their education was, as I found it, minus mathematics and science, and concluded at seventeen or earlier?

It was also the family school. Edith Stoney had been on the mathematics staff during Evie’s time as a student, although she left the term Ethel arrived, and another cousin, Anne, the daughter of Bindon Blood Stoney FRS, joined Ethel a year later. Yet, despite the influences of family and school, Ethel was led not in the Stoney tradition of science and engineering, but in a more conventionally ladylike direction to study art and music. The norm for the Edwardian era was for girls to be educated with a view to social, not academic, achievement: a good marriage was more important than any sort of technical career. So Ethel spent six months at the Sorbonne, mastering French, and perfecting her skills as a draftswoman and watercolourist. Ethel’s portrait of Sarah, her own mother, looks at me as I write this; she has captured the benignity of the older lady together with a hint of something sharper – the need to keep an eye on her daughter who might at any moment get up to no good. Aged 19, Ethel left the Sorbonne and went back to India with Evie – ‘thrown,’ as John puts it, ‘on the Indian marriage market – that is to say, she went out to India to live with her parents and her sister Evie at Coonoor. My mother and aunt seem to have led a life of singular futility, driving out in the carriage with their mother to drop visiting cards, doing little water-colour sketches of the Indian scene, appearing in amateur theatricals and occasionally attending dinners and balls.’

Julius Turing, Alan’s father, in 1907. (Author)

The days of the Raj. Ethel Turing in 1909 with a very young John perched on the Ranee Sahib’s pony, and a syce (groom). (Author)

Although this picture of the apogee of the Raj is perhaps characteristic of the period, it is not clear that it suited Ethel. For Ethel was a strikingly beautiful girl, and was not going to wait long for suitable, or even unsuitable, offers, occasionally vetoed by E.W. Stoney on the grounds of inadequate financial resources. And Julius Turing was not offering, or even in the offing. On the one hand, the over-nice late Victorian social stratifications put the covenanted Indian Civil Service – the so-called ‘heaven born’ – two notches above mere professionals like railway engineers. Engineers were people of whom you might be aware, but there were other people whom you might meet. But, in truth, the reason they did not mix socially was more mundane. Julius was not bidding in the marriage market because he was constantly on the move, and just too busy. The duties of an early twentieth-century subdivisional Indian Civil Service officer typically included being excise officer and collector of land revenue, issuer of stamps, land registrar, inspector of schools, minister of roads and irrigation, planning inspector, magistrate and district judge, food-and-drugs controller and inspector of distilleries, receiver of petitions, and preserver of the peace.

So it was by chance that they met: on a homeward-bound ship, in 1907, going by the long Pacific route, almost five years after Ethel’s return to India. On reaching Japan, Julius took Ethel to dinner, and ordered the waiter to ‘bring beer and go on bringing beer until I tell you to stop’. Ethel was bowled over, and on announcing their engagement to E.W. Stoney, who was on board as well, Julius was deemed just sufficiently solvent to be allowed to wed his daughter when they reached Dublin. Provided, of course, that the red carpet was for Mr Turing’s account.

2

DISMAL CHILDHOODS

Alan Turing was born in Maida Vale on 23 June 1912. Despite all the indications, Alan would never visit India during his lifetime, even though Julius continued in the Indian Civil Service until Alan was 13.

John Turing’s unpublished autobiography has chapters headed ‘Dismal childhood of my father’, ‘Dismal childhood of my mother’ and ‘Dismal childhood of myself’, which sums up the story of young children wrenched, in each case, away from a nuclear family. Alan, John’s younger brother, never experienced such a wrench; from the very outset he was brought up away from his parents, and on that account has been thought by some to have had the most dismal childhood of all. So much for the psychology. In the context of the times, and in the factual analysis, that easy conclusion, so readily reached from a twenty-first-century perspective, might need further scrutiny.

Fairy princess

The early childhoods of John and Alan Turing were, to all appearances, quite different. There are photographs of John, born in India in 1908, watched in his pram by a benign E.W. Stoney, being cuddled by his ayah, playing in the garden of the bungalow at Coonoor, and generally being made a firstborn fuss-of. John’s memories, given that he was sent away to England before his fourth birthday, were fuzzy but fond:1

I seem to remember the elephants and the fireflies – the largest and the smallest of my Indian acquaintances. Certainly I saw much of the elephants, for they were wont to wash themselves with great drenchings and slurpings from their trunks outside my father’s bungalow, so that I was soon in trouble with my ayah for attempting the elephant trick. In 1942 I returned to India by courtesy of the Army. In Deolali transit camp I was at once transported back to my wicker chair and little charpoy cot by the smell of burning cow-dung and the chitter of crickets in the hot Indian night.

And again, in a piece written in 1964:

I prefer to think of [my mother] as she was when I was a little boy and (as it seemed to me) a sort of fairy princess when she came to kiss me goodnight in her flouncy dinner-gown.

But John had given his parents a scare:

My mother incessantly inspected pots and pans and the habits and hands of her platoon of Indian servants but despite this rigorous watch on hygiene I contracted dysentery from infected cow’s milk and became dangerously ill. In despair my mother resolved to remove me from the heat of the plains where my father was stationed and risk the long train journey to the nearest hill station. In the middle of the night I was fluttering away but she revived me with a mammoth swig of brandy.

So Alan was born, and the boys would stay, in England. John described the trip to London as a halcyon time:

My father, perforce, had to look after me for the one and only time in his life. His solution of the problem could not have been bettered: we visited the White City, went on round-abouts, sat in restaurants and travelled around the metropolis on the tops of buses with the tickets stuck in our hat-bands. So it did not seem to me at all a bad thing that my mother should be taking a nice long ‘rest’. I was not a little astonished and put out when I was taken to the nursing home one day and found that I had a new baby brother. The decision to leave the boys in England was not easy.

Probably it was the right decision for me, for I had given my parents a bad fright with my dysentery in India and by the time my father was due for long leave again I should be seven and a half. But it was a harsh decision for my mother to have to leave both her children in England, one of them still an infant in arms. This was the beginning of the long sequence of separations from our parents, so painful to all of us and most of all to my mother.

Alan did not have a fairy princess, and his relationship with his mother would forever be asymmetrical: from her side, Alan was the baby she had left at home; for him, Ethel was, if not a princess, something not dissimilar to the queen, or, to express it differently, Mother. But that is not to say that Alan had no family when he was growing up. Quite the contrary. He had the Wards, and the Wards were, certainly, a family.

Wardship

There are two resolves that the Anglo-Indian mother will do well to make and keep so far as in her lies. In the first place, she should at least go home with her children, and see them safely launched upon their new path in life; in the second, she should register a vow, and keep it – Fate permitting – never to desert either husband or children for more than three or four years at a stretch.2

Maud Diver, novelist and Anglo-Indian, was writing guidance for women in 1909. It is implicit in her advice that sending the children home to Britain was an inevitability, part of the sacrifice implicit in the Service. And so, for the upper echelons of the expatriate community, it was. Keeping children in India was, according to one contemporary writer,3 likely to leave them puny, pallid, skinny and fretful, whereas, remarkable as it may seem to us, British food and British meteorology would convert them into fat and happy English children. Schooling in India, while theoretically available for some children of the Raj, was unlikely to be the pukka experience of a school at home, or to open the doors to a good and lucrative career. Leaving the children in Britain meant that a home had to be found for them. The historian Vyvyen Brendon explains:4

The dearth of suitable relations was a common problem for Raj families in the twentieth century. Since many [Indian Civil Service] men and army officers now came from quite ordinary backgrounds, their British relations lived in smaller houses which could not easily accommodate several extra children. To respond to the need there grew up a network of holiday homes which took in strangers’ children. Relations, whom expatriate parents did not always know very well, could turn out to be unkind or negligent while paid guardians could offer kindness and understanding to lonely children.

Rudyard Kipling had had a miserable time with his foster family, and Rudyard Kipling was a famous author, so it is all too easily assumed that all foster families were awful. Mostly the ICS families accepted the separations as their lot: an unavoidable experience about which it was not the done thing to moan, whether now or later, whether you were the parents or the children. (They also devoured Rudyard Kipling’s Anglo-Indian children’s literature: my copy of the Just So Stories has the classic drawings, and is inscribed ‘John Ferrier Turing – Prize for learning to read. from Mother. June 7 1915’.) The question for the Turings was not whether separation would happen, but who would be the boys’ foster family. Ethel Turing spent months in Britain following the birth of Alan, and she left nothing to chance.

The Wards were numerous. Colonel Ward was a veteran of the Boer War, ‘spare, gruff and taciturn, with eyes of the palest blue. His military bearing and manner concealed a warm heart.’ Mrs Ward – known to the children as ‘Grannie’ – was from another military family, the Haigs. She was ‘dumpy, resolute, outspoken, full of zest for life, sometimes severe but always meting out justice with a faintly perceptible twinkle. We both loved her very much.’ Grannie would hand out a smart biff to a child whose back was not as ramrod straight as hers. The Wards had four daughters of their own, ‘an assortment of Mrs Ward’s powerful Haig nieces’, and an incumbent boarder called Nevill Marryat, who was slightly older than John. The daughters were Nerina, Hazel, Kay – all significantly older than the boys – and Joan. John wrote acidly about Joan, but significantly said, ‘twelve years younger than Kay …, she was dreadfully spoilt and deserves no blame for making the most of it. She was half-way in age between Alan and myself and honesty compels me to admit that we both cordially detested her though not in the same way: I thought her a pest but my brother rated her a tyrant.’

The family, with a suitable retinue of servants, lived at Baston Lodge, in St Leonards-on-Sea near Brighton. The house is still there, with the requisite blue plaque. It was Victorian, Italianate and slightly rambling, situated in the lee of the church and just up the hill from the house of the African-adventure novelist Sir Henry Rider Haggard. John recalled, with a touch of envy, that Alan found a diamond and sapphire ring belonging to Lady Rider Haggard in the gutter (‘he always preferred the gutter to the pavement’). He was sent with it to the front door of the great man’s house, and was rewarded with a florin. What everyone wanted to know was what it was like inside, but on this question, alas, history is silent.

Alan’s nursery experience was longer than John’s, and different. The nursery was vigorously ruled according to old-school standards by Nanny Thompson, assisted by an under-nurse, who had her hands full with Nevill’s practical jokes (Wellington boots filled with water and so forth) as well as Joan’s tantrums. Alan was just the baby. John remembered the pre-war smells of nappies – and bacon fat, part of Alan’s diet, which for some reason was prescribed as a cure for rickets.

There was a delicious sniff of release when, leaving Julius in India, Ethel braved the menace of the U-boats to spend the spring and summer of 1915 with her boys, taking rented rooms in St Leonards. Her next visit to England would be in the spring of 1916 – again the U-boats failed to find their mark – with Julius, and this time with a holiday in Scotland into the bargain.

Baston Lodge in about 1905. (East Sussex County Council Library & Information Service)

‘Nothing in the whole range of the cussedness of inanimate objects competes with a sailor suit’ – Alan Turing in 1917. (Author)

My mother [wrote John, commenting on Ethel’s biography of Alan] does not think fit to mention that it was by no means amusing or safe to do these long sea voyages in wartime during the submarine menace, nor that a close friend of hers had been pitched into the sea when the Egypt sank and had swum around for hours before she was rescued. Forewarned, my mother carried about her person on these voyages a mass of emergency equipment for the fatal plunge. If I remember rightly it included a whistle (to attract the attention of passing ships, whales, etc.), a small Meta stove, tabloid provisions, sea-proof matches and improving literature in waterproof bindings. Happily she was never obliged to put these aids to survival to the test.

In all this, Alan’s childhood was not really different from that of other Empire children. The household was typical for an Edwardian Army family, and the horrors experienced by Rudyard Kipling at the hands of his foster mother were certainly absent. Ethel Turing had chosen well. Yet, notwithstanding the large household, the benevolent oversight of Grannie Ward, and the brisk attentions of Nanny Thompson, one is left with the sense that Alan was often left to his own devices. John, four years older, preferred to keep his nose in a book than engage with his little brother. In any case, in May 1917 John was despatched to board at prep school, and about this time Nevill also left the custody of the Wards.

Sampled snapshots

In John’s absence there was no one left to record the days of Alan’s infancy except in the endless series of sailor-suit photos. In the Christmas holidays the Turing boys were allowed to stay with the formidable Aunt Jean, Julius’s older sister:

The house, known as ‘Rushmoor’ (all their houses were called Rushmoor) was number 42, Bramham Gardens. It was one of those up and down houses of the Victorian era – a more inconvenient version of Baston Lodge but on a grander scale and with more storeys. All might have been well at Rushmoor but for that wretched brother of mine. At Baston Lodge he was not my responsibility. At Rushmoor I was held accountable for his clothes, deportment, hygiene and punctual appearance at meals. To make matters worse, he was dressed in sailor suits, according to the convention of the day (they suited him well); I know nothing in the whole range of the cussedness of inanimate objects to compete with a sailor suit. Out of the boxes there erupted collars and ties and neckerchiefs and cummerbunds and oblong pieces of flannel with lengthy tapes attached; but how one put these pieces together, and in what order, was beyond the wit of man. Not that my brother cared a button – an apt phrase, many seemed to be off – for it was all the same to him which shoe was on which foot or that it was only three minutes to the fatal breakfast gong. Somehow or another I managed by skimping such trumpery details as Alan’s teeth, ears, etc. but I was exhausted by these nursery attentions and it was only when we were taken off to the pantomime that I was able to forget my fraternal cares.

Apart from John’s account, most of which was written about his own childhood experience and (because of their difference in age) features Alan only incidentally, there are few sources on which to draw. Until Alan was four, his mother was keeping oversight remotely, through correspondence with Grannie Ward. Then, for a period, Ethel managed to get a good deal of time with Alan, since she took rooms in St Leonards when Julius returned to India in late 1916 and, saving her a further round of cat-and-mouse with the U-boats, stayed there until the end of the war.

Alan’s Kirwan cousins might from time to time invade the household – these were Ethel’s sister Evie’s children, all older than Alan. He was not one of the boisterous crowd, with their multi-bike pile-ups at the bottom of the steep hill in St Leonards and pillow fights versus the Baston Lodge maids. As with most children, Alan found his own way of dealing with all of this: if the occasion demanded it, he could put on his sailor suit smile and let the waves flow past. In 1919 and 1922 there were more Scottish trips when the Turing parents came home again on long leave. Alan went fishing with his father and on mountain walks with Mother. Ethel noticed a change in Alan when she came home in 1921: ‘From having been extremely vivacious – even mercurial – making friends with everyone, he had become unsociable and dreamy. I decided to take him away from his pre-preparatory school, where he was not learning much anyway, and teach him myself for a term and by attention and companionship get him back to his former self.’5

Before long, in early 1922 it was time to join John at boarding school. Hazelhurst had that inestimable quality of the small British preparatory school of the twentieth century. It had only 45 boys aged 8 to 13, giving everyone a chance to achieve in something, in particular sport. The Turing parents were not sporty:

My father [continues John] was considerably indulged by his mother, so that she contrived to have him excused from all games and athletics at Bedford. One direct result of this mollycoddling was that he could never summon up the faintest interest in games. My modest prep-school achievements – such as the magnificent 21 against Crowborough Grange which saved the side! – were wholly ignored. My brother’s even more artful and singular feats of non-gamesmanship were totally ignored in like manner: it would be a distortion to suggest that they were tacitly discouraged, certainly not – they were ignored.

Only such past masters of the art of passive resistance as my brother Alan could fail to count themselves athletes [in the small school]. When he in turn outdistanced us all and became a marathon runner of Olympic standard, he attributed his success to his running away from the ball at Hazelhurst. ‘He believed that it was at his preparatory school that he learnt to run fast, for he was always so anxious to get away from the ball’: so wrote my mother. But it isn’t true: he propped himself on his hockey stick and studied the daisies.

John might have been over-harsh about his parents’ attitude to sports: the Hazelhurst Gazette reports that on Saturday 11 March 1922, the hockey season had opened with the fixture School v The Staff. ‘J. F. Turing (inside right) – rather slow, but combines well: a very poor shot’ – was playing for School. Both Mr and Mrs Turing had been co-opted to play for the Staff. The Staff won 6–1. The Hazelhurst Gazette prudently did not offer commentary on the performance of individual members of the Staff team.

Perhaps Hazelhurst’s greatest asset was its headmaster, W.S. Darlington. Mr Darlington wrote up the school magazine every term, and this gives us a wry insight into Alan’s time at prep school. For the first term all was not easy, since John (due to go to Marlborough imminently) was head boy and Alan was the youngest in the school. The Hazelhurst Gazette hinted at Alan having made his mark immediately. First he started an origami craze: ‘not just darts and paper boats which all of us knew how to make, but paper frogs, paper kettles, paper donkeys, paper hats of all sizes and shapes. Seemingly you could boil water in a paper kettle over a naked flame – so Alan assured all the lower echelons, who were now industriously acquiring his skills and dropping paper all over the place.’

Practical skills were honoured at Hazelhurst. Naturally, there was scouting: Mr Darlington commented, in his benignly sardonic way, on the deterioration in fire-lighting technique in his report for May 1922. But more importantly, there was carpentry. From time to time the excitement of carpentry got the better of Mr Darlington:6

As we sit down to write, we can only think of doors, doors, dovetails and bookshelves! As we think of the first of these our memories go back a term or two when we mentioned a door as being still unfinished. Oh! just as it was receiving the final touches before being put together, one of those final touches was too much for one of the tenons and it broke off; our present belief is that the door of happy memory is not yet finished, but we are quite sure the maker has learnt much more in the way of joinery than one who only puts together about six pieces of wood, more or less decently planed up, and then calls the article a book-case.

The sporting life. Alan is fully devoted to something on the hockey field. (© The Estate of P.N. Furbank and reproduced by kind permission of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge)

And there was also the triumph of the geography exam, to which all the school were subjected. Alan had been poring over maps, both at Baston Lodge and at school, and this habit had caught Mr Darlington’s eye. ‘We departed somewhat from our usual custom,’ writes Mr Darlington on the subject of end-of-term exams: there was an ‘innovation [which] took the form of three prizes, one for each division of the school, for filling in blank maps with given names. The experiment was popular and successful.’ Successful for some, but not so popular with everyone. Turing II distinguished himself with 77 marks, beating by a wide margin all the other boys in his division and all but five in the whole school; Turing I, despite being top of Form I, mustered only 59 marks. The end-of-term song celebrating the forthcoming holidays included the shameful line: ‘and no Map will make an Elder Brother take a lower place’.

Another perspective on Alan’s time at Hazelhurst is provided by Alan himself, in his letters home, of which 16 survive. Most of the letters are dated, and all but two bear Sunday dates. Like many prep schools, it seems that Hazelhurst obliged its pupils to write a letter home as part of the regular Sunday routine. Children at prep school have no idea what to write about to their parents; the weekly letter can be an ordeal for all involved, particularly given that even in the 1920s it would take at least a month for a letter to get to India from Sussex. It seems that Ethel kept these 16 – and then gave them to King’s College, Cambridge, in 1960 – because they actually have something of interest in them. No tales of magnificent 21s against Crowborough Grange can be found in this collection, then. The ones that remain, though, have more than something of interest; here are some from the sample:7

• (1 April 1923): ‘Guess what I am writing with it is an invention of my own it is a fountain pen like this:– [diagram follows]’

• (undated, summer 1923): ‘This week I thought of how I might make a Typewriter like this [uninterpretable partly crossed-out diagram follows] you see the the funny little rounds are letters cut out on one side slide along to the round and along an ink pad and stamp down and make the letter, thats not nearly all though’

• (8 June 1924): ‘I do not know whether I told you last week but once when I said how much I hated tapioco pudding and you said that all Turings hated tapioco pudding and mint-sauce and something else I had never tried mint-sauce but a few days ago we had it and I found out very much that your statement was true.’

• (21 September 1924): ‘in Natural wonders every child should know it says that the Carbon dioxide is changed to cooking soda in the blood and back to carbon dioxide in the lungs. If you can will you send me the chemical name of cooking soda or the formula better still so that I can see how it does it.’

Many of the letters contain meticulous accounting in accordance with Julius’s standing requirements, and an inordinate proportion go on about Alan’s handwriting, which appears to have been an obsession with Ethel. And perhaps of greatest interest is that, from the very earliest, the letters all begin with the startling salutation ‘Dear Mother and Daddy’. Here is fertile ground for psychologists, so perhaps it is not necessary to add any commentary. John corroborates the conclusion, easily reached from these letters, that Alan was already showing a bent towards mathematics and sciences at Hazelhurst, and this early indication was to influence the choice of Alan’s public (secondary) school.

Alan Turing as THE WIDOW in the Hazelhurst School play in 1925. (Author)

Natural Wonders, by E.T. Brewster, does deserve some particular commentary. Ethel gave Alan’s copy to the Sherborne School Archive, and inside it she wrote: ‘Natural Wonders Every Child should know was given to Alan Turing aged 10½. This book greatly stimulated his interest in science and was valued by him all his life.’ Alan had, however, developed an interest in the sciences (as well as geography) at an earlier age: Ethel mentions in her own biography of Alan how he was trawling gutters with a magnet to pick up the iron filings left by iron-tyred cartwheels, and asking questions about the bonding of hydrogen to oxygen in water in 1921; he had been reading other nature-study materials aged seven; and at the age of eight he had written ‘a book entitled About a Microscope – the shortest scientific work on record for it began and ended with the sentence, “First you must see that the lite is rite”’.

Hazelhurst followed the traditional preparatory school curriculum. The ‘preparation’ offered by the school was for the Common Entrance examination to public schools, which was introduced in 1904, with papers in Latin, French, English, and Mathematics, plus a General Paper (Scripture, History and Geography). Greek could also be taken; so could Latin Verse. Science did not make it onto the core curriculum until 1969. Science at Hazelhurst was covered through occasional lectures on Natural History. It was fun, but it was not mainstream. To indulge his interests, Alan was having to make his own way; but that was fine, it was the way that suited him.