9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Everyone knows the story of the codebreaker and computer science pioneer Alan Turing. Except … When Dermot Turing is asked about his famous uncle, people want to know more than the bullet points of his life. They want to know everything – was Alan Turing actually a codebreaker? What did he make of artificial intelligence? What is the significance of Alan Turing's trial, his suicide, the Royal Pardon, the £50 note and the film The Imitation Game? In Reflections of Alan Turing, Dermot strips off the layers to uncover the real story. It's time to discover a fresh legacy of Alan Turing for the twenty-first century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise for Reflections of Alan Turing

‘Fascinating and highly readable ... My wife Rohini and I feel particularly grateful to have a special link to [Alan Turing] through our house in Coonoor … where Alan’s mother lived for many years’

Nandan Nilekani, Chairman and Co-Founder of Infosys

‘Essential reading for anyone who thinks they know the history of Alan Turing … a significant reappraisal of his meaning for us today’

Dr Tilly Blyth, Head of Collections, Science Museum

‘Dermot compels us to learn from his uncle’s incredible life and many achievements in our own pursuit of creating a better world for all’

Liz Carr, Actress and Comedian

About the Author

Dermot Turing spent his career in the legal profession before turning to writing. His biography of his uncle, Alan Turing Decoded, is widely acclaimed, and his book X, Y and Z: The Real Story of How Enigma Was Broken won the Polish ‘Guardian of Memory’ prize in 2019. His other books include The Codebreakers of Bletchley Park and The Story of Computing.

In addition to writing, he is a trustee of The Turing Trust, a charity which refurbishes old computers in order to equip schools in Africa, and keeps up his interest in the legal issues relating to financial market infrastructures. He is a visiting fellow at Kellogg College, Oxford.

www.dermotturing.com

First published 2021

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Dermot Turing, 2021, 2022

The right of Dermot Turing to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 707 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Family Trees

Foreword by Kayisha Payne

Reflections

Raj

X-Ray

Compute

Geheim

Robot

Postbag

Apple

Icon

Notes

Further Reading

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In some ways, this is an unconventional book, and bringing it to life would not have been possible without the support and contributions of many people.

Foremost, I must thank Laura Perehinec of The History Press and Katie Read of Read Media for nurturing the idea from the beginning and helping shape it. Inspiration has come from many sources: the blog of Margaret Makepeace at the British Library pointed me to the story of John William Turing; Edith and Florence Stoney now have their own biography by Adrian Thomas and Francis Duck, from which I learned a great deal; Professor Juliet Floyd’s writings on Alan Turing in connection with philosophy have deepened my understanding of his work; and Dr James Peters gave me access to the new Alan Turing archive at Manchester University, which I have drawn on extensively to interpret Alan’s final years and his relationships with colleagues and correspondents. Also in Manchester, the discoverer of the new Turing papers Professor Jim Miles not only gave his encouragement but also told me about Alan Turing’s calculating machine. In Cambridge, and notwithstanding the problems of lockdown, Dr Patricia McGuire arranged the spectroscopic imaging of correspondence redacted by my grandmother so we could try to find out what she wanted to hide; I am in debt to the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge, and to Maciej Pawlikowski for making that possible.

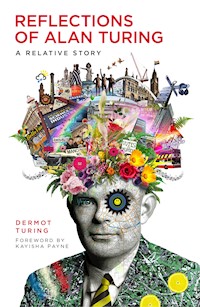

In the United States, I was able to find out about the secret Army Bombe project with the help of Dr Philip Marks and the ever-helpful staff of the National Archives Records Administration. The cover image of Alan Turing is also an American creation: commissioned by Princeton University and painted by Jordan Sokol, it is a stunning addition to the iconography and I am grateful to them both for allowing it to be used here. A different approach to art is taken by Justin Eagleton whose quirky and imaginative images allow us to look at Alan Turing in new ways: thanks to him as well for being involved in the project. Others whose various contributions have guided me along the way include Rachel Hassall, Andrew Hodges, Serena Kern-Libera, Kriti Majan, Jezz Palmer, Jonathan Swinton and Colin Williams: thank you to you all.

A special thank you is due to Kayisha Payne for being involved in the project and for all the work she is doing to advance the prospects of young black people in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Quotations from Alan Turing’s letters, located in the archives at King’s College, Cambridge and the University of Manchester, are made possible with the kind permission of the Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge. Quotations from Beatrice Worsley’s letters in the Manchester archive are made with kind permission of Alva Worsley.

FAMILY TREES

FOREWORDBY KAYISHA PAYNE

As a young Black woman studying for a master’s degree in Chemical Engineering at university, I knew what it was to feel different. I was amongst a minority of woman on the course and an even smaller minority being Black. This was the year 2017 – around sixty-three years after Alan Turing lived and worked – yet many aspects of his story resonate with my experience.

Alan was most famously known for his intellect but, as with every person, there is so much more beneath the surface. The complexities of our lives are often hidden behind our achievements and successes but are equally as important; they are the context of our story. This book unearths many aspects and influences in Alan’s life; the one which resonates most with me is his experience of race, which is the basis of my non-profit-organisation, BBSTEM – Black British Professionals in STEM.

The idea for BBSTEM came about whilst I was still studying. By chance I was introduced to a Black British chemical engineer and, as we spoke, I was inspired by him and the story of his career journey. I had never met another Black person in the same field as me. Afterwards I reflected on this meeting and how much value could be gleaned from a meeting that happened accidentally; imagine what could be achieved if a specific community was created with a purpose to help Black people see themselves in scientific and engineering roles as a career, and have a forum where they could ask questions without any judgement? I founded BBSTEM with the aim to encourage, enable and energise individuals in business, industry and education to widen participation and contribution of Black individuals in the field of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). A big part of our work is to inspire young Black people to get involved in these subjects at school and beyond, and to show the younger generation that a successful and exciting career in STEM is achievable.

Though Alan Turing may not have faced the same obstacles as the young people we work with at BBSTEM, the message still resonates: we can overcome life’s challenges and reach our goals through hard work and resolve. Our life circumstances do not have to limit us. There are also lessons we can learn from his legacy about persistence, determination and being true to yourself. Just because someone says you’re wrong or you can’t do it doesn’t make it so; indeed, like him, you could prove people wrong and go on to become a British icon!

Unlike when Alan was alive, STEM subjects are no longer mainly theory or science fiction. The possibilities to discover and create are infinite. It’s an exciting time to get involved in STEM, for old and young people alike. ‘Geeky’ is no longer a negative. In an age of portable and wearable technology, the people who know how it works and how to create it are the new heroes. And the opportunities to rise to the top, if that’s where you want to go, are becoming more open to everyone, regardless of background, gender, sexuality, ethnicity or anything else.

This book needed to be written. It is a story of inspiration; of the struggles of life; of resilience; of achievement; and, perhaps most importantly, of legacy. We all deserve to leave a legacy which is fair and true. Dermot, Alan’s nephew, eloquently reveals the puzzle pieces of Alan Turing that the world has never been privy to and allows readers to see the full picture of this man’s extraordinary life. All of us have something to learn from him.

As we enter a year in which the United Kingdom is celebrating Alan Turing’s contribution by making him the face of the new £50 note, let’s reflect on the building blocks that make up the story of our own lives and how they make us who we are. Let’s celebrate ourselves, our community and our diversity. Let’s focus on the future.

Kayisha Catherine Ibijoki Payne

December 2020

REFLECTIONS

We all own a bit of Alan Turing now. He has become an icon, a symbol, a personification of ideals which he never was in his lifetime, a public screen onto which we can project our own image of what we would like him to stand for, something of which to be proud. His work and life story have inspired the creation of plays, statues, songs, feature films, poems, sound-and-light displays, and even scientific conferences. Many of these are the offspring of a standard narrative of Alan Turing’s career, which can be simplistically summed up as ‘the heroic codebreaker who was persecuted for being homosexual and killed himself as a result’.

In this book, I will show that the standard narrative is largely wrong. Alan Turing was not really a codebreaker – he spent little time on it, and few of the many achievements of Bletchley Park can be ascribed to Alan. He was no war ‘hero’ even if his crucial part in the design for the Bombe machine (a success story resulting from teamwork, not Marvel Comics superhero magic) enabled vital intelligence to be generated in volumes unimagined before World War Two. In fact, Alan Turing was far more than a codebreaker, and it is almost disgraceful that we allow his achievements in other fields to be overshadowed by this, and by the mis-step by which he brought down upon himself the attentions of a hostile police force, leading to his conviction for ‘gross indecency’. The excessive, almost prurient attention given to Alan’s trial and subsequent treatment has allowed us to define him by his sexuality; worse, we have woven a morality myth, in which Evil Forces drive an Innocent Victim into an Abyss of Despair. Alan Turing was no victim and his death was unrelated to the hormone treatment imposed upon him following his trial. We should reappraise the standard narrative and rediscover in Alan Turing the things which he himself could be proud of.

The process of rediscovery begins with Alan Turing’s origins and family background. He was a child of the Empire – an Empire which was becoming technocratic and scientific while clinging to a racist, gender-biased view of different people’s rightful roles in society. These things were in the background for the developmental period of his life, and it is perhaps remarkable that Alan Turing did not turn out to be racist or misogynist. Instead, he quietly supported a Jewish refugee boy from Austria and his (much older) friend from childhood, Hazel Ward, in her missionary work in Africa, as well as his frustrated scientist-manquée mother, with whom relations were rarely good. Unashamedly, I want to look at Alan Turing within the context of his family – my family; not, therefore, as the isolated Victim of the standard narrative, but as someone doing extraordinary things in a rather ordinary context. And in doing so, we can rediscover an Alan Turing who had many friends, an acid sense of humour, an irritating stammer, and an intolerance of what my grandfather called ‘humbug’ and these days we would call bullshit.

I am often asked what ‘stories’ about Alan were told at home during my childhood. The subtext of the question is an imagined family scene with crumpets toasting round the winter fire and the excuse for rose-tinted reminiscence. I am afraid my answer is a disappointment. There was no fire, and Alan Turing was not a subject for discussion. He died in 1954, and during my childhood in the following decade the circumstances of his death were still raw and not for exposure. Only when my grandmother – the author of the first, and until 1984, only, biography of Alan Turing – died in the mid 1970s did things begin to change. At the same time, the astonishing fact of Bletchley Park’s successes broke news, and the possibility that Alan Turing had been involved in some way became known. My father rediscovered pride in his younger brother and, in a short chapter in one of his many unpublished books, felt able to write a counterblast to his own mother’s 1959 hagiography of Alan. Alan Turing had, in a sense, been the inventor of the computer, which had earned him a Fellowship of the Royal Society – which was pretty amazing in itself – and now there was the added thrill of a key role in breaking Enigma at Bletchley Park.

That meant that Alan Turing’s influence on my own life was subtle. In the early 1970s, Bletchley was still a tightly kept secret. Few people had any experience of a computer, and the knowledge of Alan Turing’s contribution to computer science was limited to exactly that small group of specialists who had studied this rarefied field. But it certainly motivated me. I followed in his footsteps to Sherborne School, where it seemed strange that it was the biology building, not the computer room, that had been named after him. At least the school had a computer, which was unusual for the time.

After school, I followed Alan to King’s College, Cambridge. This again was a deliberate choice: if he had gone there, that was the road to follow. And I suppose it was, partly, because of Alan’s legacy that I chose to study science subjects there, though subsequently I realised that my skills probably lie elsewhere and I did not, in the end, make science my career.

In the thirty-five or so years since I left university, all that has changed. The Bletchley story, coupled with the standard narrative of Alan Turing’s life story, has resonated strongly with the public. It is right, and humbling, for people to want to know more. But this is not a biography. Rather, this is about how events in Alan’s background – his family, his life, and his achievements – could stimulate us to think about ourselves and our own society. Although it is Alan Turing that brings us to this reckoning, it is for us to grow his legacy.

The legacy of Alan Turing is not just about codebreaking and information security, or even his ground-laying work in computer science or biology or mathematics, though I believe he would much rather have been remembered for these things than his personal story. His story is certainly not a licence to indulge in the false nostalgia of a war won by force of intellect rather than the foul business of killing, nor even to congratulate ourselves for our modern liberalism towards homosexuality. Instead, I suggest that Alan Turing’s legacy, seen in the context of his origins and achievements, is an agenda. To use his own words, ‘We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.’ I hope you agree, and that you will find inspiration in this mirror on the life of someone truly remarkable.

RAJ

It was daunting enough for any young man of 16 to be summoned to the Company’s offices in Leadenhall Street, even if only to appear before the Committee of Shipping. The streets of London were filthy and dangerous and quite alien to someone born on a different continent. The business of the Committee was somewhat alien too, reflecting the changing nature of the Company. For it was 1791, and the office had become something more than an administrative base for a trading operation: it was turning itself into a House of Government, and within five years the classical but modest frontage would be deemed inadequately grandiose, the buildings on either side acquired, and the whole lot knocked down to be replaced by a neo-Roman temple: because that’s what you need if you aspire to Empire. The young man in question was John William Turing, a junior officer in the service of the Honourable East India Company, and he was in London to hear his fate.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when the Turings arrived in India, but it was certainly no later than 1729, when Dr Robert Turing was appointed surgeon’s mate at Fort St David, about 100 miles south of Madras. Robert and his elder brother John, sons of a minister of the Kirk, left Scotland, joining the trade boom to India. One way or another, Turings would be in India almost continuously for over 200 years, from before the birth of the Raj until the moment of its demise.1 To my mind, Alan Turing ought to have been born in India.

Dr Robert Turing seems to have managed all right: he settled in Madras in 1753, and married the widow Mary Taylor in 1755. He had a nice if ‘remote’ house just to the south of the Government Garden. Its situation was not altogether convenient, since the French siege of Madras began in December 1758 with first the British, and then the French, army deciding that Dr Turing’s garden was a good place to begin operations. Robert’s three children survived the excitement of two armies in their yard, and then began establishing their own army of interbreeding Turings to populate Madras. To achieve that, it was necessary to import some more Turings from Scotland. A couple of cousins, active in trade, came over in the 1760s: John and William.

John Turing married one of Robert’s girls, Mary, in 1773, despite being related to her at least twice over. This didn’t stop them having nine more Turing children, including some called John, Robert, William and Mary, all the better to confuse the genealogists. John’s brother William Turing was, as well as being a trader, employed by the East India Company. He too had a family: a wife, Nancy, and children, John (born 1774) and Margaretha (born 1783, who died while a baby). Curiously, a family history prepared in 1880 states, ‘he died unmarried and without lawful issue’ in 1782; and William himself is omitted from a family tree prepared in 1849. A marginal note elsewhere in the history gives a clue to these oddities, saying that John ‘had a brother William … whose social relations as revealed by his will would account for [another family member] not having heard of him’. What appalling revelations could the will contain? ‘Having so many Bad debts its impossible to Say how my Estate may turn out,’ it says, ‘therefore I leave my natural Son John William 2000 Pags my Girl Nancy 2000 Pags and Child She is big with 2000. W Turing.’ William, who wrote his will on 15 November 1782, was dead by mid-January 1783, and it fell to his brother John to sort out the bequests. The estate accounts explain that cash was paid to ‘the Girl Nancey or Roja Horstain in full of her Legacy left to her by the Deceased’.2

So that’s it. William’s Girl Nancy was Indian. It was an old-style partnership, one which was common enough in the early days of British presence in India, and which horrified the Victorian descendants far more than serial intermarriages with cousins. It was that same John William Turing (whose own legacy was still owed to him in December 1783, awaiting the calling-in of a number of debts, some owed by other members of the Turing family) who was in London, in 1791, appearing before the Committee of Shipping of the Honourable East India Company:

The Chairman of the Committee acquainting the Court that John Turing who is nominated as a Cadet for Madras appears to be a Native of India; Mr Turing was called into Court, And having withdrawn; It was moved, and on the question, Resolved Unanimously, That no Person the Son of a Native Indian, shall henceforward be appointed by the Court to employment in the Civil Military or Marine Service of the Company.

The ‘Honourable’ Company condemned him, without the need even for a hearing, because of the colour of his skin. No more is known about my mixed-race ancestor John William Turing.

Dr Richard Wilson, a surgeon at Trichinopoly, recognised that grown-up unadopted Anglo-Indian children should not be ignored. In 1778, he wrote to the Governor and Council of the Company:

This Class of People is sufficiently numerous to merit the Attention of Government, than which no better Arguments, I think, can be advanced to evince the Necessity of converting them into Servants of the Publick. I shall then attempt … to proceed to point in general the Methods by which this vagrant Race may be formed into an active, bold and usefull Body of People, strengthening the Hands of Dominion with a Colony of Subjects attached to the British Nation by Consanguinity, Religion, Gratitude, Language and Manners.3

It was for the Company to address the problem of people marooned halfway between cultures. And the Company did, although it wasn’t until 1793 that the ‘Cornwallis Reforms’ took hold in India. This Cornwallis was the general who had surrendered at Yorktown a decade before, and when he became the first Governor-General of India, his mission was to reform the Company into a more professional civil service. To Cornwallis, this meant Europeanisation: all Indian and Anglo-Indian officials in posts worth more than £500 a year were sacked. John William Turing’s treatment had been simply a foretaste of the way Empire was going to look from now on. The celebrated historian William Dalrymple has described how mixed-race children disappear gradually from wills made by the British in India in the early years of the nineteenth century. He reckons that the biggest surprise is that the existence of people like John Turing surprises us: ‘It is as if the Victorians succeeded in colonizing not only India but also, more permanently, our imaginations.’4

So what has this gothic ramble through the cobwebs of history got to do with Alan Turing? While a recurrent theme in this book is prejudice and discrimination, it would be a little absurd to suggest that Alan Turing’s life was in any way shaped by the events of 1791. But a genuine question for me is how much Alan Turing’s own mindset was influenced by his Indian, or more specifically Empire, heritage. To solve this equation, we have to go forward a few decades.

The Turings seem to have been mercifully absent from India when the upheaval took place which, when I was at school, was still called ‘the Indian Mutiny’ (more of that Victorian brainwashing, when nowadays we recognise it to have been an uprising for independence). By the time the Turings were back on stage, the transformation of India from a trading partner to an imperial client had been completed, and the roles for them were as civil administrators of the Empire. My grandfather Julius Mathison Turing arrived in 1897 in (where else?) the Madras Province with all the requirements of a young member of the Indian Civil Service (ICS): impeccable marks in the exam, a crash-course in Tamil, and an expectation that a 20-something-year-old history student from Oxford could become the embodiment of law courts, town planning department, education ministry, water board, inland revenue and you-name-it. In this late Victorian world of spice, tweed and sweat there was no trade in sight, and certainly no mixed-race people in any position to confuse the distinction between the governors and the governed.