11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

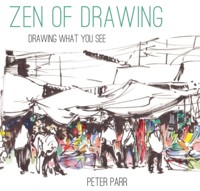

Zen of Drawing inspires you to pick up a pen, pencil or an iPad and start drawing what you see with a 'zen' approach. Author Peter Parr has spent his career in animation successfully teaching people to draw and encouraging students to nurture their skills through observational drawing. He advocates a fresh way of looking closely at your subject and enlisting an emotional response, in order to fully appreciate the nature of what you are about to draw. You will learn that whatever you are drawing, it is essential not only to copy its outline but also to ask yourself: is it soft, smooth or rough to the touch? How heavy is it? Is it fragile or solid? Then, having grasped the fundamental characteristics, or zen, of the object, make corresponding marks on the paper – crisp textures, a dense wash, a scratchy or floating line. The chapters cover: keeping a sketchbook; tools (pen, pencil, charcoal, watercolour and iPad); perspective; line and volume; tone and texture; structure and weight; movement and rhythm; energy, balance and composition.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 85

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

ZEN OF DRAWING

ZEN OF DRAWING

Peter Parr

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE – THE SKETCHBOOK

A sketchbook in the hand is worth two in the bag

CHAPTER TWO – NEW HORIZONS

A method of breathing and drawing fresh air

CHAPTER THREE – DEVELOPING DRAWING SKILL

Speaking lines without words

CHAPTER FOUR – TOOLS

Finding the right tool for the job

CHAPTER FIVE – MARK-MAKING

Breathing sensuality and life

CHAPTER SIX – LIFE FORCES

The mountain imitates the dancer

CHAPTER SEVEN – MAKING A PICTURE

Rise to every occasion

CHAPTER EIGHT – A GROWING ARCHIVE

From the back to the front

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

HOW TO TAKE A PEBBLE FROM THE BEACH

Barton Beaches

Brush pen and watercolour, 2012

42 x15cm (16½ x 6in)

Becton Bunny Beach

Black pencil, 1986

21 x 58cm (8¼ x 22¾in)

My aim in this book is to introduce you to a stimulating new approach to drawing that combines mark-making with inspiration taken from drama and dance. It will offer you a radical change in the way you look, think and draw, so I hope the book will encourage you to pick up a sketchbook and pencil and really go for it.

Today we live in a world of ever-decreasing attention spans and demands for high-speed responses which make it increasingly difficult for us to find the time to refresh our senses through observational drawing and reflection. However, if you are willing to create the necessary space, you will reap the benefits. In the following pages I would like to share with you the value that can be found by keeping a sketchbook: taking time out and stopping to consider, to look, and then to really see.

Many of the illustrations I have used were created spontaneously, catching a moment in time or made in a period of reflection. It has been my aim to encourage students to nurture their skills through observational drawing, and on many occasions they have said that my sketches look like finished artworks. Although the initial inspiration may have been something fleeting that caught my interest, my sketches are indeed finished artworks that now wait for their moment as inspirational reference in future projects.

The practice of gathering information, by first looking and then drawing, is always beneficial, no matter how or what you have gathered; your sketches will in some way inform and improve your skills.

Sketching is a pleasure; what I would call the ultimate experience of ‘taking a pebble from the beach’, but this new method of drawing leaves the pebble in place and untouched, while the captured sketch goes on to inspire your future work.

The reward and pleasure gained from engaging in the act of seeing and then drawing cannot be overestimated. So I invite you to collect your pencils, pens, paper or iPad and take part in a new and exciting way to draw.

Christchurch Old Mill

2B pencil, 1986

21 x 29cm (8¼ x11½in)

Avebury, Wiltshire Stone Circle

Coloured pencil, 1986

21 x 29cm (8¼ x11½in)

CHAPTER ONE

THE SKETCHBOOK

A sketchbook in the hand is worth two in the bag

Salisbury Cathedral Close

2B pencil, 1986

21 x 29cm (8¼ x11½in)

This chapter will show how a sketchbook can become a travelling companion with which to share memories, or simply an archive in which to store your findings and meditations.

Back and forth went the chunky wax crayons clenched in little fists, making marks all over the paper – no time to stop, only to change colours again and again, densely layering the paper. Neither child could say what the marks were meant to represent, but neither did they care – they were just excited to have made a drawing.

Most children have had drawing books in which to tell stories, remember things or just play. Sadly, at the age of eight or nine they start to become dissatisfied with their drawings because they wrongly assume that they should be accurate representations of reality. What a mistake, for at that moment a very special instinct starts to wither and could eventually die. Those who survive this stage go on to become more confident in their ability to draw, making it a life-long hobby or even their way of making a living.

Photo Ciaran Parr

For centuries, both urban and rural environments worldwide have been marked with graffiti expressing someone’s desire to be noticed and remembered: ‘I was here!’ This graffiti is from Gloucester Cathedral and a forest oak.

Mark-making is a basic human instinct – our natural way to interpret or describe what we see, indicating that our senses are indeed alive and responding to our environment.

Whenever you’re out walking, carry your sketchbook in your hand as this allows you to make an instant record of whatever catches your eye. Packed away in a bag, it is not really with you. It is the feel of the book in your hand, reminding you of its presence, that prompts your curiosity.

Each of your scribbles made, good or bad, will build the important stepping-stones that are so much a part of the creative process. Don’t be tempted to tear pages from your book. A sketch should be kept, as it will almost certainly be used sooner or later, no matter how slight it may seem at the time. Its primary value to you was its creation – an immeasurable benefit to your wellbeing.

Annecy Old Town

Brush pen, 2009

21 x 58cm (8¼ x 22¾in)

My sketchbooks are a collection of drawings that keep me visually alert and up to speed, in much the same way that actors rehearse or athletes work out to keep fit. I can recall from them more detailed information than ever I can from a rapidly snapped photograph.

Once my interest is caught and my eye alerted, I quickly and intuitively ask myself, ‘What materials would best suit the subject? Should I try a new method of drawing?’ Then I cut to the chase and draw.

Sketchbook gallery – a random selection of sketches made from life in my sketchbooks.

Decorated Elephant, Ahmedabad

Brush pen and watercolour, 2011

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

Note the weighty mass of this working elephant.

Chilling out, Annecy Brush pen, 2009

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

Here I took advantage of a relaxed life model for free.

Farm Fowl

Watercolour, 2011

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

The humble farmyard chicken can be just as interesting to draw as a peacock.

Spring Garden

Watercolour, 2012

21 x 29 cm (8¼ x 11½)

A garden in bloom offers the chance for floods of colour.

Fame City Poolside, Texas

Watercolour, 1986

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

Keeping a sketchbook to hand encourages you to make freestyle impressions from life such as this.

Berlin Cathedral

Brush pen, 2010

21 x 42cm (8¼ x 16½in)

This sketch conveys the architectural weight and energy of an imposing building.

Camel Drivers

Watercolour, 2009

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

Here the dynamism of the upright figure contrasts with the more relaxed figures behind him.

Tunisian market

Brush pen and watercolour, 2009

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

A market is a good place to find vibrant colour and activity.

Byron

Pencil, 1981

21 x 13cm (8¼ x 5¼)

Surrounding dark pencil work simplies the face.

Annecy Castle

Brush pen and watercolour, 2005 21 x 29cm

(8¼ x 11½)

Warm and cool watercolour washes enrich the stonework.

An open invitation No matter where I might be drawing in the world, it seems to be an activity that attracts attention. If I were writing in a notebook no one would try to read it, but an artist is considered to be fair game, offering an open invitation for public scrutiny. The most extreme example was at the Great Wall of China when a group of tourists flipped through the pages of my sketchbook as I was drawing, and then with polite nods of the head moved on. Over the years I have become immune to this kind of attention and so I just carried on drawing regardless. It can be daunting for an inexperienced artist, but try not to let it put you off – the interest shown is usually well-meant.

Penhurst, Kent

2B pencil and watercolour, 2003

21 x 58cm (8¼ x 22¾)

Here I was gathering information on people, architecture and colours.

Domes and Crosses

Pen, ink and watercolour, 2010

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

Small reference studies are an aid to finished paintings.

This compilation of sketches is presented in the order that I drew them in my foldout concertina sketchbook.

Trying out a concertina sketchbook for the first time, I thought it would be fun to create a collection of sketches that could unfold like a scroll, 3m (10ft) long, to record my three-day visit to the Venice Biennale in 2007.

Your sketchbook can become a place in which to broaden and preserve your drawing progress, building a resource that will inform your work. It will become a treasury of memories and playfulness, which can lead you to discovery and fulfilment in your drawing. The fact that you have a sketchbook and use it regularly to observe, draw and have fun is a testament to your commitment to finding your path as an artist. I guarantee that once you have formed the habit of using a sketchbook you will feel lost without one.

CHAPTER TWO

NEW HORIZONS

A method of breathing and drawing fresh air

Telamon

Fine point and Caran d’Ache, 1992

21 x 29cm (8¼ x11½in)

Wheel hub

Watercolour, 1986

21 x 29cm (8¼ x 11½)

This chapter opens up a new approach to drawing by combining breathing and timing in much the same way that musicians, actors and dancers employ timing in their form of art.

Even in speech and writing, we use phrasing as timing. When we draw, we can recognize timing by feeling the way we apply our mark-making. This encompasses all marks without exception, not just one type of mark.