17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

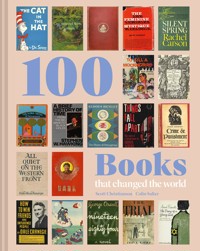

A chronological survey of the world's most influential books. Many books have become classics, must-reads or overnight publishing sensations, but how many can genuinely claim to have changed the way we see and think? In 100 Books that Changed the World, authors Scott Christianson and Colin Salter bring together an exceptional collection of truly groundbreaking books – from scriptures that founded religions, to scientific treatises that challenged beliefs, to novels that kick-started literary genres. This elegantly designed book offers a chronological survey of the most important books from around the globe, from the earliest illuminated manuscripts to the age of the ebook publication. Entries include: The Iliad and The Odyssey, Homer (750 BC), Gutenberg Bible (1450s), The Quran (AD 609–632), On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Nicolaus Copernicus (1543), Shakespeare's First Folio (1623), Philosophae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton (1687), The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith (1776), The Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Mary Wollstonecraft (1792), On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin (1859), Das Kapital, Karl Marx (1867), The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud (1899), The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank (1947), Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung (1964), A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking (1988).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

100 BOOKS

that changed the world

100 BOOKS

that changed the world

Scott Christianson and Colin Salter

This book is dedicated toScott Christianson (1947–2017)

Contents

Introduction

c. 2800 BC

I Ching

c. 2100 BC

The Epic of Gilgamesh

c. 1280 BC

Torah

c. 750 BC

The Iliad and The Odyssey, Homer

620-560 BC

Aesop’s Fables

c. 512 BC

The Art of War, Sun Tzu

475–221 BC

The Analects of Confucius

400 BC–AD 200

Kama Sutra, Vatsyayana

380 BC

The Republic, Plato

c. 300 BC

Elements of Geometry, Euclid

20 BC

De Architectura, Vitruvius

79

Naturalis Historia, Pliny the Elder

609–632

The Quran

800–900

Arabian Nights

c. 1021

The Tale of Genji, Murasaki Shikibu

1308–21

The Divine Comedy, Dante

1390s

The Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer

1450s

Gutenberg Bible

1532

The Prince, Machiavelli

1543

On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, Nicolaus Copernicus

1550

Lives of the Artists, Vasari

1557

The Prophecies, Nostradamus

1605

Don Quixote, Cervantes

1611

King James Bible

1623

Shakespeare’s First Folio

1665

Micrographia, Robert Hooke

1667

Paradise Lost, John Milton

1660–69

Samuel Pepys’s Diary

1687

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton

1726

Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift

1753

Species Plantarum, Carl Linnaeus

1755

Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary

1764

The Castle of Otranto, Horace Walpole

1776–88

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon

1776

The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

1791

Rights of Man, Thomas Paine

1792

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Mary Wollstonecraft

1812

Grimm’s Fairy Tales

1813

Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

1818

Frankenstein, Mary Shelley

1829

Procedure for Writing Words, Music and Plainsong in Dots, Louis Braille

1836

Murray’s Handbooks for Travellers

1844–46

The Pencil of Nature, William Henry Fox Talbot

1845

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

1847

Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë

1850

David Copperfield, Charles Dickens

1851

Moby-Dick, Herman Melville

1852

Roget’s Thesaurus

1854

Walden, Henry David Thoreau

1857

Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert

1858

Gray’s Anatomy

1859

On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin

1861

Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management

1862

Les Misérables, Victor Hugo

1869

Journey to the Center of the Earth, Jules Verne

1865

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

1867

Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

1867

Das Kapital, Karl Marx

1869

War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

1884

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

1891

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Oscar Wilde

1895

The Time Machine, H.G. Wells

1899

The Interpretation of Dreams, Sigmund Freud

1913–27

Remembrance of Things Past, Marcel Proust

1915

The Origin of Continents and Oceans, Alfred Wegener

1917

Relativity: The Special and General Theory, Albert Einstein

1922

Ulysses, James Joyce

1925

The Trial, Franz Kafka

1927

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Walter Y. Evans-Wentz

1928

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D.H. Lawrence

1929

All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque

1936

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, John Maynard Keynes

1936

How to Win Friends and Influence People, Dale Carnegie

1946

Dr. Spock’s Baby and Child Care

1947

The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank

1948 and 1953

Kinsey Reports

1949

1984, George Orwell

1949

The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir

1950

A Book of Mediterranean Food, Elizabeth David

1954

The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley

1955

Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov

1954–55

The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien

1957

On the Road, Jack Kerouac

1957

The Cat in the Hat, Dr. Seuss

1958

Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe

1960

To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee

1962

Silent Spring, Rachel Carson

1962

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Alexander Solzhenitsyn

1963

The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan

1964

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung

1967

One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez

1969

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Maya Angelou

1972

Ways of Seeing, John Berger

1974

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert M. Pirsig

1988

A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking

1988

The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie

1991

Maus, Art Spiegelman

1997

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, J.K. Rowling

2013

Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty

2014

This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate Naomi Klein

Acknowledgements

Index

An original copy of the 1450s Gutenberg Bible – the first book to be printed using movable type. Colourful hand-painted decorations have been added to this opening page. (See here.)

A nineteenth-century woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada showing a scene from what is often hailed as the world’s first novel, The Tale of Genji (c. 1021) by Murasaki Shikibu. (See here.)

Introduction

What’s your favourite book? Why did it inspire you? Did it make you laugh? Or cry? Or gasp with wonder? Did it change your world? Now imagine trying to choose a hundred, not just from your own shelves, not just from your local library, but from the entire history of the written word.

So how do you choose? Where do you start? This book starts at the very beginning with a 4,800-year-old text, the divinatory I Ching, which predicts the future based on the toss of six coins. We end ninety-nine books later in the twenty-first century with another prediction, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything, which forecasts the end of the planet if we don’t act collectively to mend our ways. On the pages in between, our list is drawn from every age, in every style and on every subject. All of them have changed their readers’ worlds, and ours.

The oldest printed texts were stamped into clay while it was still wet, then baked into permanence. As handwriting developed, it became easier to copy texts out onto sheets of papyrus, vellum, or paper. But it would still take a team of monks several years to produce a single beautifully illustrated manuscript copy of the Bible. The world was truly changed with the invention of printing. The Bible was the first book to be printed with movable type, in the 1450s. Although it took Gutenberg three years to print roughly 180 copies of it, it was significantly faster than a team of monks.

SCIENCE AND MAGIC

Mass production of books not only lowered the cost but enabled the faster spread of knowledge and the exchange of ideas. In the wake of Gutenberg’s invention, the first scientific volumes start to appear on our list of world-changing books. Copernicus leads the way in the modern era with On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres (1543). We’ve included Robert Hooke’s microscopic images (Micrographia, 1665), Isaac Newton’s mathematics (Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, 1687) and Carl Linnaeus’s classification of species (Species Plantarum, 1753). Each of them benefited from the exchange of ideas in books, combined with the insights of their own particular genius. Each in turn was read by others; Henry Gray’s Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical (1858), Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and Albert Einstein’s Relativity (1917) were all, as Newton put it, ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’ who had gone before them. Books carry new knowledge forward into the future.

Printing had the same world-shrinking impact as the development of the Internet five hundred years later. Nowadays, you can share information or ask questions with friends and colleagues on the other side of the globe almost instantly. Or you can send emojis: not all text messages change the world, after all.

The publication of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres in 1543 contradicted fourteen centuries of belief by stating that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the centre of the universe. (See here.)

A plate from William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature (1844–46), the first commercially published book illustrated with photographs. (See here.)

Nor do all books. But the oldest-known work of literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2100 BC) is here. It’s a Sumerian tale of gods and men that today might be described as magic realism. Joining it are more recent combinations of magic and reality, including The Arabian Nights from the ninth century and Gabriel García Márquez’s 1967 novel One Hundred Years of Solitude. Literature makes magic across the millennia.

INNER AND OUTER WORLDS

Storytelling makes up a large part of our list. Looking back, we admire the fiction of earlier centuries for what it reveals about the times in which it was written. Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1390s), for example, or Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), are snapshots of time and place. But for their first readers, as well as their modern ones, those ancient works of literature captured something more: the human condition. The best literature shows us the best and worst of ourselves. We are all flawed, and it is easier to see the flaws in others than in ourselves, especially if, as in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726), they are transferred to completely imaginary worlds. But we all have goodness, too, embodied in fiction’s heroes. Don Quixote shows us a remarkable nobility of spirit, no matter how misguided. Harry Potter, another character on a quest, is a model for the moral strength we all wish we had.

Good literature changes our inner world by helping us to understand human behaviour. Sometimes it goes further and changes the world around us. Charles Dickens’s observations of Victorian poverty were instrumental in improving the conditions of the working class. Alexsander Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch (1962) was the first chink of light to be shed on the secretive cruelty of Stalin’s gulags, a revelation that contributed eventually to the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Books can be exquisitely beautiful objects, but what concerns us here is their inner beauty, the power of their words, their capacity to startle us into new ways of thinking with just a few well-chosen letters. Words can be powerful in many ways: evocative, emotive, persuasive, prescriptive, informative, misleading, lyrical, musical, incomprehensible, revealing. Words can do whatever a good author wants them to do for his or her readers.

Religious writing is perhaps the most powerful of all and therefore the most dangerous, as well as the most inspiring. The Torah, the Quran and the Bible all make it onto our list; but so too do books that show the ugliness of excessive religious zeal. Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl (1947) and Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991) are very different but equally compelling records of the Nazi persecution of the Jews. Salman Rushdie lives under constant threat of assassination because his 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses, offended devout Muslims.

BIG IDEAS AND HELPING HANDS

Books of both fiction and fact can change the world. Somewhere between them, it could be argued, lies philosophy, another way of trying to explain the human condition. Each age seems to throw up its own way of interpreting how we behave, or ought to behave. Times change, and we change with them, with the help of books. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War (c. 512 BC) gives way to Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532); Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776) is challenged by John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936); Karl Marx’s Das Kapital (1867) is revisited in Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013).

Books have been particularly instrumental in changing the attitude of men toward women, and of women towards themselves. Thomas Paine’s 1791 political thesis The Rights of Man was followed a year later by Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, an early feminist milestone. Our selection also includes Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963).

Books don’t have to contain big ideas to change their worlds. Some books just want to help you with everyday life at work and at home. So we’ve included the domestic bible Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), which transformed the lives of middle-class women in the nineteenth century, as Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food (1950) did in the twentieth. Dale Carnegie’s business advice from 1936 still teaches us How to Win Friends and Influence People more than eighty years after its publication. The Kama Sutra (400 BC–AD 200) and the Kinsey Reports (1948 and 1953) on sexual behaviour are two very different approaches to the same subject, two thousand years apart.

CHANGING YOUR WORLD

Of our one hundred books, there are fifty that everyone would agree should be included. About the other fifty, almost everyone will disagree. Should Jung be in and Freud out? Should it be David Copperfield or Great Expectations? Robert M. Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance or Mark Zimmerman’s Essential Guide to Motorcycle Maintenance? Why The Cat in the Hat over Green Eggs and Ham? Why Mao and not Lenin?

There are a lot of books out there. In the United States, every year roughly one book is published for every thousand people in the population. That’s more than 300,000 new books every year. In the United Kingdom it’s even more: one book for every 350 people. And in China the figure falls even further, to just over 300 people per book – that’s 440,000 new books or new editions every year, in China alone. The global total is about 2.25 million new publications. Every year. We hope that 100 Books that Changed the World is a modest but worthy addition to the world’s library. If it makes you question your own choices or ours, or introduces you to a book that eventually changes your world, then our work is done.

The publication of D.H. Lawrence’s unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960 marked a crucial step towards the freedom of the written word and helped usher in the sexual revolution of the 1960s. (See here.)

I Ching

(c. 2800 BC)

No other book in history has so much embodied the culture that produced it and influenced that culture for so long as China’s ancient divination text, the I Ching.

The creation of the I Ching, or Book of Changes, is thought to lie as far back as 2800 BC, making it the oldest text still in continuous use. Its origins remain shrouded in legend, but it is generally agreed that the diagrams date to around 2800 BC, the text to 1000 BC, and the philosophical commentaries on it to 500 BC. The diagrams are credited to Emperor Fu Hsi, who was inspired by the markings on a tortoise to create the hexagrams that formed the basis of the I Ching.

For centuries it was known as the Zhou Yi, until in 136 BC, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty named it the first among the classics, pronouncing it the Classic of Changes, or I Ching. The I Ching is a book of divination, or geomancy, where objects – originally yarrow stalks – are cast on the ground and the patterns they form are interpreted through the use of hexagrams, which are given meaning and significance by reference to the book.

Although there is no verified author, the text of the I Ching is thought to have originated in the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BC). What started out as a method of predicting the future, of interpreting good and bad omens, was given deeper meaning by the addition of philosophical commentaries known as the ‘Ten Wings’.

The most important element of the Ten Wings is the Great Commentary. This elevated the spiritual significance of the I Ching, describing it as ‘a microcosm of the universe and a symbolic description of the processes of change.’ An individual who takes part in the spiritual experience of the I Ching, it maintained, could understand the deeper patterns of the universe.

The Ten Wings were traditionally attributed to Confucius, giving gravitas to the text and helping to maintain its importance throughout the Han and Tang dynasties.

The I Ching offers a unified understanding of China’s two main contending spiritual traditions – Confucianism and Taoism – both of which are rooted in it. It considers the dynamic of two opposite principles: one negative, dark and feminine (yin); one positive, bright and masculine (yang), whose interaction influences the destinies of creatures and whose harmony gives birth to other creations. The text examines the infinite range of dynamic reactions set up by the interplay of yin and yang, within the sixty-four possible six-line statements that make up the I Ching.

Its philosophy is said to include three basic concepts: change, ideas and judgements, which indicate whether a given action will bring good fortune or misfortune, remorse or humiliation. The I Ching stresses the importance of caution, humility and patience in one’s daily living. It reminds the reader that great success is often followed by difficulty, and great hardship is often necessary for subsequent achievement.

After the Xinhai Revolution deposed the last emperor in 1911 and China became a republic, the I Ching was no longer considered part of mainstream Chinese political philosophy. However, psychologist Carl Jung was fascinated by it and introduced an influential 1923 German translation by Richard Wilhelm. The book was taken up by the counterculture of the 1960s and has continued to influence writers through the twentieth century, including Philip K. Dick and Herman Hesse.

John Blofield’s 1965 translation coincided with the emerging countercultural movement that was looking to the East for spiritual meaning and direction.

This annotated copy of the I Ching dates from the twelfth century AD, when it was being redefined as a work of divination rather than philosophy.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

(c. 2100 BC)

This four-thousand-year-old tale of gods and men was rediscovered by archaeologists in the Middle East during the nineteenth century. It is the oldest work of literature ever recorded and contains universal characters and themes that would not be out of place in any modern cinematic epic.

Gilgamesh was a real person, a Sumerian king of the city-state of Uruk around 2700 BC. The earliest examples of writing, from 3300 BC, have been found in Uruk, the ruins of which lie in modern-day Iraq. In the centuries following Gilgamesh’s death he achieved a mythical, godlike status in popular memory.

The earliest known stories about him, stamped by unknown authors onto clay tablets, date from around 2100 BC. Over time these stories and others were combined to form The Epic of Gilgamesh that we know today. Fragments of this combined history have been found dating from 2000 BC. Modern translations are based largely on an almost-complete version of the epic written down on twelve tablets in about 1200 BC – some 1,500 years after Gilgamesh’s death – which was discovered in 1853 by archaeologists.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a tale of two halves. The first is a sort of buddy movie. The gods, alarmed at wicked King Gilgamesh’s despotic behaviour, create an opposite to rein him in, a morally upright man called Enkidu. After fighting, the two become firm friends. In the course of their subsequent adventures they offend the gods, who decide to punish Enkidu with death.

Gilgamesh is grief-stricken and contemplates his own mortality. Part two is a classic road movie in which he sets off to find the secret of eternal life from Utnapishtim, the only survivor of a great flood. After many encounters and dangers along the way, Gilgamesh is forced to accept that death is built into every man’s life, but that humanity, and human achievement, will endure. He returns to Uruk a changed man and becomes the mature, wise ruler whom his people (and we) will remember long after his passing.

The themes of The Epic of Gilgamesh – friendship, mortality, a voyage of self-discovery – are eternal and can be traced in the literature of every age from then until now. The story of Gilgamesh had a direct influence on two other ancient texts: the Bible and the works of Homer. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey are both tales of epic journeys with lessons learned on the way. The Old Testament of the Bible contains several episodes that almost copy passages from The Epic of Gilgamesh, notably descriptions of the Garden of Eden and the Great Flood in which Utnapishtim becomes Noah.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is the oldest written story so far discovered, and its value is enhanced by the existence of so many versions written over a period of 900 years. The use in its text of often-repeated phrases suggest that it comes from an even older oral tradition of storytelling dating back to the time of Gilgamesh himself. And if nineteenth-century archaeologists could find this epic, who knows what others remain to be discovered?

Known as Tablet V, this 2000–1500 BC fragment from The Epic of Gilgamesh was discovered in 2015 by the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Iraq.

Torah

(c. 1280 BC)

The guide to Jewish daily life for more than three thousand years, the Torah provides the basis for Jewish law and practice. Jewish scholars have summed up its overall teaching in a single sentence: ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself.’

The Torah consists of five books – Bereshit, Shemot, Vayikra, Bamidbar and Devarim – which correspond to the first five books of the Christian Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The books describe the origin of mankind in the Garden of Eden and the early leaders of the tribe of Israel, including Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. It describes the escape from Egypt to Mount Sinai; the delivery of the Torah, including the Ten Commandments and other instructions; and the punishment for not obeying them. The Torah concludes with the death of Moses and the entry of the Israelites into Canaan, the land promised to them by God.

Although often translated from the Hebrew as ‘law’, the word ‘Torah’ more accurately means ‘instruction’ or teaching. Specifically, the Torah consulted by Jews is the Torah of God or the Torah of Moses. By tradition this Torah existed before the world was created. God offered it to all the peoples of Earth, but only Israel accepted. Moses, leader of the Israelites, received it from heaven in 1312 BC and wrote it down over the next thirty to forty years.

Modern scholars believe more prosaically that the five books were written by several different authors over many centuries before coalescing as the Torah around 700 BC. While orthodox Jews hold it to be the strict law of God, more liberal Jews see it as a set of guidelines rather than rules, in the same way that some Christians no longer accept the literal truth of the Bible. Islam also accepts the historic existence of the Torah. There are several references to it in the Quran, although Muslims hold it to have been corrupted by human error – the careless transcription of it by scribes over the ages.

The Torah is still transcribed by hand onto scrolls. Tradition demands strict accuracy of the 304,805 Hebrew characters that make it up. It is a painstaking process, a work of profound faith and calligraphic art, executed according to precise rules of style and lettering, which can take eighteen months to complete.

It is a requirement of Judaism that every Jew own such a copy of the Torah. For at least two thousand years Jews have heard or spoken the same prescribed passage of the Torah on the same day in a year-long cycle of readings. The Torah not only embodies the tenets of the Jewish religion but emphasizes its ancient tradition. It is, with Hinduism and Zoroastrianism, one of the oldest systems of belief in the world, and the Torah is its book.

Like all scrolls of the Torah, this nineteenth-century North African copy is handwritten in ink on parchment. If an error is introduced in transcription, it renders the text invalid.

The Iliad and The Odyssey Homer

(c. 750 BC)

Two of the greatest epic poems were composed three thousand years ago by a mysterious blind man in ancient Greece. These seminal works of Western literature tell the heroic stories of characters caught up in a city’s brutal siege and a warrior’s long and perilous journey home.

Precious little is known about Homer, including whether he even existed or if he was a composite character. Some accounts say he was born around the eighth to ninth century BC on the island of Chios in the Aegean Sea and probably lived in Ionia, an ancient region of what is now Turkey. In a field rich in academic speculation, some believe he was a court singer and storyteller who became blind.

Homer is credited with having composed the two great epic narrative poems, The Iliad and its sequel The Odyssey, around 750 BC. The date has been arrived at from statistical modelling of the evolution of language, although some historians believe it to be older. What is almost certain is that both works arose from the oral tradition and were intended to be performed, not written down.

The Iliad, sometimes known as The Song of Ilion, depicts a few weeks in the final year of the ten-year siege of the city of Troy. Organised into twenty-four books, it tells the story of the great warrior Achilles and his heroic battle against Hector of Troy and his quarrel with King Agamemnon.

The Odyssey tells the story of the Trojan War hero Odysseus (known as Ulysses in Roman translations) as he makes a perilous ten-year journey home to Ithaca, a small island off the west coast of Greece, once the siege is ended. After his long absence, it has been assumed that Odysseus is dead, and his wife, Penelope, and son, Telemachus, must contend with a group of ardent suitors who compete for Penelope’s hand in marriage.

‘Tell me, muse, of the man of many resources who wandered far and wide after he sacked the holy citadel of Troy, and he saw the cities and learned the thoughts of many men, and on the sea he suffered in his heart many woes.’

Odysseus, like Achilles before him in The Iliad, is offered a choice: he may either live in comfort and be immortal like the gods, or he may return to his wife and his country and be mortal like the rest of us. After choosing the latter, he struggles to complete his journey and is constantly confronted with questions about human mortality and the meaning of life.

Both books were composed in Homeric Greek – an amalgam of Ionic Greek and other ancient Greek dialects. The oldest known fragments of The Iliad, written on papyri and discovered rolled up in the sarcophagi of mummified Greek Egyptians, date to 285–250 BC and are displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The Iliad and The Odyssey are the two oldest extant works of Western literature. They represent the earliest recorded form of storytelling and have inspired writers from every generation, from Euripides and Plato, to James Joyce with Ulysses (1922) and Margaret Atwood with Penelopiad (2005), a retelling of the Odyssey from Penelope’s perspective.

The title page of the first English-language edition of Homer’s works, published in London in 1616, with translations by the English dramatist and poet George Chapman.

Venetus A is the oldest complete manuscript of The Iliad. Dating to AD 900, it is preserved at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice.

Aesop’s Fables

(620–560 BC)

One of the earliest and greatest collections of fables was written in prose in ancient Greek and traditionally ascribed to a deformed slave named Aesop, who gained great fame for his storytelling ability. The distinctive tales were originally performed for adults but later became standard bedtime fare for young children.

A fable is a short, simple tale that features animals or inanimate objects as characters to impart a truth and teach a moral lesson about the human condition. Isaac Bashevis Singer, the great modern Jewish fabulist, called the fable maybe ‘the first fictional form’ and noted that ancient man believed myths and fables were true but not necessarily factually accurate, just as a child can grasp that such a lesson might contain a deep truth beneath an obvious falsehood. Fables are also pessimistic in their point of view.

As Aesop tells it, in ‘The Wolf and the Lion’: ‘A Wolf, having stolen a Lamb from a fold, was carrying him off to his lair, when he was stopped by a Lion, who seized the Lamb from him. The Wolf protested, saying, “You have unrighteously taken that which was mine!” To which the Lion jeeringly replied, “It was righteously yours, eh? The gift of a friend?”’

The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–c. 425 BC) mentioned ‘Aesop the fable writer’, whom he described as a slave from Phrygia (now Turkey) who had won his freedom by telling fables and enjoyed the company of the beautiful courtesan Rhodopis. Aesop’s fame was so great that his name was also cited by Socrates, Aristotle, Aristophanes, Plato, Pliny and a host of other ancient writers.

Many historians believe that Aesop’s fables had been passed on by oral tradition dating back in some instances much further than the sixth century BC; a few have been traced back on papyri 800 to 1,000 years earlier. The ones he told apparently were not collected and written down until three centuries after his death. Throughout later periods, including the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, additional fables were added to the list ascribed to Aesop, although they had actually come from other times and cultures that had no relation to the former slave. Over time they had been refined and adapted, while retaining their original simplicity and cogent message.

Ancient Greek and Latin manuscripts repeated Aesop’s fables, and versions of the tales were among some of the earliest subjects translated and printed across Europe, further enhancing his reputation as a fabulist. To be accepted into the genre, subsequent additions had to meet a number of criteria: They had to be plain and unadorned, brief and true to nature in their depiction of animals and plants. Their context and concluding moral were also crucial. And they had to impart timeless, universal truths.

Versions have been published in countless forms and languages. Aesop’s fables have been dramatised on the stage and in movies, set to verse and music, adapted in cartoons, and performed in dance.

For centuries the fables were primarily aimed at adults, but in 1693 the English philosopher John Locke advocated tailoring them to ‘delight and entertain a child’, along with illustrations that would appeal to young people. Since then Aesop’s fables have been a staple of children’s literature, and the names of the stories (‘The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing’, ‘The Goose that Laid the Golden Egg’, ‘The Boy Who Cried Wolf’) have become a part of common vernacular.

In ‘The Raven and the Fox’, the vain bird is smooth-talked into dropping its morsel of cheese. This woodcut illustration is from William Caxton’s printing of 1484.

A woodcut portrait of Aesop from the first English edition of the fables, printed in 1484 by William Caxton.

The Art of War Sun Tzu

(c. 512 BC)

Although it was written two and a half millennia ago, an ancient Chinese treatise that is packed with wise advice about warfare strategy and tactics has remained a must-read by generations of military commanders, business leaders and competitors of all sorts. Its tenets are credited with many victories, large and small.

Sun Tzu, or Sunzi, is reputed to have lived during the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history that ran from about 722 to 470 BC, at the height of ancient China’s golden age. Little is known about him or the sources of his expertise, other than that he was a military general and philosopher who is credited as the primary author of The Art of War.

In his day, as dozens of small feudal principalities developed their own competing ideas and philosophies, they increasingly battled one another for supremacy, and warfare assumed a more central role. After Sun Tzu’s death, one of his descendants, Sun Ping of Chi, repopularised the wise philosopher’s treatise in about 350 BC. It’s said that The Art of War played a large role in reshaping and unifying ancient China, which became history’s most stable and peaceful empire.

As one of China’s Seven Military Classics, Sun Tzu’s work achieved such fame in Asia that even illiterate peasants knew it by name, and generations of combatants memorised much of its contents. Over time the book has remained one of the definitive classics on waging war.

The author considered war as a necessary evil that must be avoided whenever possible. He also offered sage advice about how to win a war and what not to do when contending with one’s enemies. ‘The art of war is of vital importance to the State,’ he wrote. ‘It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry which can on no account be neglected.’ In his view, ‘The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.’

The text is composed of thirteen chapters, each of which is devoted to instructing commanders on a specific key aspect of warfare. Sun Tzu presents five constant or fundamental factors to be taken into account in warfare deliberations: the way (moral law), heaven (seasons), earth (terrain), leadership (the commander), and management (method and discipline), as well as seven elements that determine the outcomes of military engagements.

Although Sun Tzu is generally agreed to be the primary author, many historians argue that the treatise may have been modified over time as new developments occurred in warfare, such as the introduction of cavalry. The earliest known bamboo copy of the work, known as the Yinqueshan Han Slips and unearthed in Shandong in 1972, has been dated to the Western Han dynasty of 206 BC to AD 220, and it is nearly identical to modern editions of The Art of War. The first European edition occurred in France in 1772, and the most famous English version, by Lionel Giles, first appeared in 1910.

Many of the book’s precepts hold true for activities besides warfare. ‘If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.’

The first English edition to gain recognition was Lionel Giles’s 1910 translation. It is still in print today.

These inscribed bamboo strips are the oldest known copy of The Art of War. Known as the Yinqueshan Han Slips, they date from 206 BC to AD 220.

The Analects of Confucius

(475–221 BC)

An ancient Chinese philosopher compiled a collection of wise sayings that offered ethical principles to regulate the five relationships of life – the relationships of prince and subject, parent and child, brother and brother, husband and wife, and friend and friend – and his guidance has been followed for thousands of years.

Confucius (c. 551–479 BC) was a philosopher and politician who had grown up in the shi (gentry) class and spent many years compiling wise sayings to guide individuals in their daily lives, according to ethical principles.

‘Analect’ means a fragment or extract of literature, or a collection of teachings. In the case of Confucius it also refers to a discussion or verbal exchange of moral and ethical principles. The Analects of Confucius took the form of Confucian teachings and thoughts, along with fragments of dialogues between the philosopher and his disciples.

Compiled and written by Confucius’s followers during the Warring States period (c. 475–221 BC), The Analects are considered among the most representative works of Confucian thought, and they still exert great influence on Chinese culture and East Asia. Many scholars believe that the analects were later refined into their final form during the mid-Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) to become a central text of Chinese culture. Regarded as a foundational work in Chinese education for nearly two thousand years, the Analects continued to be officially used in civil service examinations until the early twentieth century. Although they were frowned upon under the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, they continue to shape the morality and thoughts of millions of Chinese, upholding the central virtues of decorum, justice, fairness and filial piety.

One of the key concepts of Confucianism is ren, which stands for a comprehensive set of ethical values that include kindness, benevolence, humaneness, altruism and goodness. The Analects teach how to cultivate and practise ren in speech, action and thought. Modesty, self-deprecation, humility, and self-discipline are prized as essential virtues, which flow from the Chinese equivalent of the Bible’s Golden Rule: ‘Do not do to others what you would not like done to yourself.’

The Analects use the term ‘junzi’ for an ideally ethical and capable person, while ‘dao’ is a teaching, skill, or art that is a key to some arena of action. ‘Zhong’ denotes loyalty; ‘xin’ stands for trustworthiness; ‘jing’ for respectfulness and attentiveness; ‘xiao’ means obedience to one’s elders; ‘yong’ is courage or valour.

The Analects provided guidance in dealing with others in every aspect of an individual’s life, including self-awareness: ‘Have no friends not equal to yourself.’

The hallmark of Confucian teaching was its emphasis on education, study and knowledge. ‘When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it – this is knowledge.’

The Analects is one of the four great Confucian texts known as the Four Books, and it has been one of the most widely studied works in China for the past two millennia. Its combination of wisdom, philosophy and social morality continue to influence Chinese culture and values today.

Imaginary portrait of Confucius from the frontispiece of Confucius Sinarum Philosophus (Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese), published in 1687 in Paris.

A Yuan dynasty (AD 1279–1368) edition of The Analects, including scholarly commentary.