11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

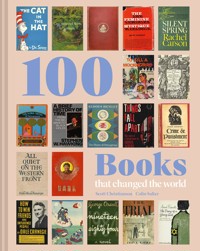

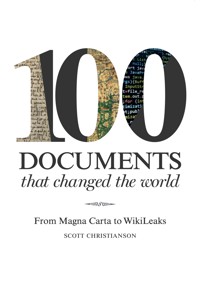

100 Documents That Changed the World brings together the most important written agreements, declarations and statements in history. The documents included here have changed the course of history by rewriting laws, granting freedoms and laying out constitutions. But as well as official charters and presidential proclamations, there are also the hand-written documents that have gone on to shape the way we think, the scrawled notes that mark breakthroughs in the worlds of science and technology, and the annotated manuscripts that have become literary landmarks. Documents included: Magna Carta (1215); Shakespeare's First Folio (1623); Declaration of independence (1776); Constitution of the United States (1787); Louisiana Purchase (1803); Darwin's Evolutionary Tree (1837); Gettysburg Address (1863); Treaty of Versailles (1919); German Surrender (1945); Martin Luther King, Jr's "I Have A Dream" speech (1963); First Website (1991); Edward Snowden Files (2013).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 289

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Magna Carta (see here).

From Magna Carta to WikiLeaks

SCOTT CHRISTIANSON

Contents

Introduction

2800 BC

I Ching

1754 BC

Code of Hammurabi

c. 750 BC

Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey

512 BC

The Art of War

408 BC–AD 318

Dead Sea Scrolls

c. 400 BC

Mahabharata

400 BC–AD 200

Kama Sutra

c. 380 BC

Plato’s Republic

AD 50

Gandharan Buddhist Texts

AD 609–632

The Quran

1215

Magna Carta

1252

Ad Extirpanda

1265–74

Summa Theologica

1280–1300

Hereford Mappa Mundi

1450s

Gutenberg Bible

1478–1519

Leonardo da Vinci’s Notebooks

1492

Alhambra Decree

1493

Christopher Columbus’s Letter

1501

Petrucci’s Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A

1517

Martin Luther’s 95 Theses

1521

Edict of Worms

1522–25

Journal of Magellan’s Voyage

1542

Destruction of the Indies

1582

Gregorian Calendar

1611

King James Bible

1620

Mayflower Compact

1623

Shakespeare’s First Folio

1632

Galileo’s Dialogue

1649

Execution Warrant of Charles I

1660–69

Samuel Pepys’s Diary

1660s–1727

Isaac Newton Papers

1665

First Printed Newspaper in English

1689

English Bill of Rights

1755

Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary

1776

Declaration of Independence

1776

The Wealth of Nations

1787

Constitution of the United States

1789

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

1791

Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen

1803

Louisiana Purchase

1803

Meriwether Lewis’s List of Expenses

1804

Napoléonic Code

1822

Deciphering the Rosetta Stone

1826

First Photograph

1833

Slavery Abolition Act

1837–59

Charles Darwin on Natural Selection

1844

First Telegram

1848

The Communist Manifesto

1852

Roget’s Thesaurus

1854

John Snow’s Cholera Map

1854–63

First Underground Train System

1861

Fort Sumter Telegram

1863

Emancipation Proclamation

1868

Alaska Purchase Cheque

1869

War and Peace

1878

Phonograph

1899

The Interpretation of Dreams

1912

Sinking of the Titanic

1916

Sykes–Picot Agreement

1917

Balfour Declaration

1917

The Zimmermann Telegram

1918

Wilson’s 14 Points

1919

19th Amendment

1919

Treaty of Versailles

1920

Hitler’s 25-Point Programme

1922

Uncovering Tutankhamun’s Tomb

1929–31

Empire State Building

1936

Edward VIII’s Instrument of Abdication

1936

Television Listings

1938

Munich Agreement

1939

The Hitler–Stalin Non-Aggression Pact

1941

Declaration of War Against Japan

1942

Manhattan Project Notebook

1942

Wannsee Protocol

1942–44

Anne Frank’s Diary

1945

Germany’s Instrument of Surrender

1945

United Nations Charter

1946–49

George Orwell’s 1984

1947

Marshall Plan

1948

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

1949

Geneva Convention

1950

Population Registration Act

1953

DNA

1957

Treaty of Rome

1961

John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address

1962

Beatles’ Recording Contract with EMI

1963

Martin Luther King, Jr., “I Have a Dream”

1964

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung

1964

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

1969

Apollo 11 Flight Plan

1976

Apple Computer Company

1981

Internet Protocol

1990

Two Plus Four Treaty

1991

First Website

2001

“Bin Laden Determined to Strike in US”

2002

Iraq War Resolution

2006

First Tweet

2007

WikiLeaks

2011

3D Map of the Universe

2013

Edward Snowden Files

Acknowledgements

Index

The Declaration of Independence – the birth of a nation and one of the most significant landmarks in the history of democracy (see hee).

doc·u·ment

noun \ dä-ky -mənt, -kyü-\

an official paper that gives information about something or

that is used as proof of something

a computer file that contains written text

1. a:

an original or official paper relied on as the basis, proof or support of something

b:

something (as a photograph or a recording) that serves as evidence or proof

2. a:

a writing conveying information

b:

a material substance (as a coin or stone) having on it a representation of thoughts by means of some conventional mark or symbol

3. a:

a computer file containing information input by a computer user

ORIGIN Middle English, precept, teaching, from Anglo-French, from Late Latin & Latin; Late Latin documentum official paper, from Latin, lesson, proof, from docere to teach.

FIRST KNOWN USE 15th century

Introduction

We live in the Age of Documents. They are the signposts of our history and the currency of 21st-century life. In the digital era documents have become even more ubiquitous as they are infinitely viewed, produced, reproduced and archived. We are flooded by them in our everyday existence; they both enrich and clutter our lives. Documents have become integral to the way people think; we use them to navigate through our current world and connect to the past.

Of course not all documents are in themselves important or worth saving. Yet we rely on certain documents to tell us what is new and important, just as we consult others to learn about history. Without authentic documentation, recorded and preserved, there would be no inscribed remembered history and we would have no knowledge of the distant past.

Although the definition of ‘document’ has continued to evolve and expand, as evident from the dictionary meanings shown opposite, it seems reasonable to expect that documents will continue to be even more important in the digital future and beyond. How could they not?

By viewing documents in historical perspective, as this book does, we gain a window onto the vast artefactual record of knowledge, civilization, power, and society. 100 Documents That Changed the World presents a variety of notable examples in all forms, from the last 5,000 years of human existence. The documents are time capsules that take us into the minds of their creators and the historical situations that impelled their creation.

The chronological listing reflects the changing material form of documents, as the historical record shows the earliest documents recorded in bamboo, silk slips, carved stones, and papyri, to finely printed manuscripts, paper documents in hand-print and type, and computerized files that collect and synthesize big data.

The different types or genres of documents presented include decrees and proclamations, holy books, legal codes, treaties and secret agreements, official warrants and certificates, patents, literary classics, philosophical treatises, diaries and letters, business contracts and commercial records, memoranda and electronic messages, and data maps, all of which made a significant mark in history.

There are government documents, church records and private communications, some of which appear as works of art but most of them simply impart important information – plain documents that nevertheless started or ended wars, inspired religious worship for millions, or advanced the cause of science or human rights to new heights.

The Gutenberg Bible – the first book to be printed with metal movable type – changed the nature of document production (see here).

Jean-François Champollion’s code for deciphering the Rosetta Stone held the key to two forgotten languages (see here).

Several of the authors of these documents are among the great figures in history: Christopher Columbus, Leonardo da Vinci, Martin Luther, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Abraham Lincoln, Sigmund Freud, Thomas Edison and Martin Luther King, Jr. Others are lesser known players: Shakespeare’s appreciative fellow actors; the guilt-ridden conquistador Bartolomé de las Casas; the eccentric lexicographer Samuel Johnson; the meticulous polymath Peter Mark Roget who always sought to use the right word; and the eighteenth-century French feminist Olympe de Gouges, who was beheaded for her courageous women’s rights manifesto. There are also kings and queens, generals, popes, presidents, bureaucrats and computer hackers.

While we generally need not consult the original handwritten manuscript of the Declaration of Independence in order to grasp the meaning of such a document, the artefact itself has enormous symbolic importance and the act of looking at it takes on the quality of ritual. Important original documents possess an ‘aura’ that transcends their content and purpose, and renders them enormously valuable – even priceless – in need of state protection and conservation. Such documents embody and encode such large-scale, historic concepts as national identity, human rights, world-changing wars, massive transfers of wealth and population, and seminal scholarship in the arts and sciences. Thus readers of this book who cannot travel to the institutions in which the documents are housed, get to glimpse the oldest known versions as well as images of some of their makers and learn something of their background and context.

Some of the documents described here clearly altered the course of history – legal documents such as the Code of Hammurabi, Magna Carta, or United States Constitution; rulers’ decrees such as the Alhambra Decree, Edict of Worms, or Emancipation Proclamation; famous treaties and secret pacts such as the Sykes-Picot Agreement and Treaty of Versailles; religious tracts such as the Dead Sea Scrolls or the Quran; and assorted other accounts.

There are also a few iconic documents that have influenced popular culture and modern media – the Beatles’ EMI recording contract, the first TV listings, the documents that founded the Apple Computer Company, as well as the first website and the first tweet.

Each carries a story, and many of these are woven with the others to form a documentary history.

Human beings have sought to preserve important documents for as long as civilizations have existed. Archaeologists have discovered archives of records made of clay tablets, papyrus, and other materials, going back to the ancient Mesopotamians, Chinese, Persians, Greeks and Romans (who called them tabularia) in the third and second millennia BC. Such accumulated historical records were important in their day for helping to maintain order and continuity in legal, military, administrative, commercial and social affairs, keeping track of taxes, crimes, victories and other vital statistics. Long kept by governments, churches, corporations and other private entities, archives have also provided a key building block of historiography, communicating to posterity historical information about previous regimes, cultures and events. Archivists have always been selective, however, saving only those records deemed worthy of retention and special care.

In the beginning, each document was unique, like a work of handmade art. But as its stature grew, copies or replicas were made, and as those copies deteriorated more copies of copies were made by scribes so as to preserve the sacred work. Unfortunately, many of these manuscripts perished over time. But some ancient works survived – the I Ching, Dead Sea Scrolls, Mahabharata and Plato’s Republic being a few examples.

Later there were also translations and copies made that had been mechanically reproduced by printing and other means. In some instances the printing of an authorized version, such as the King James Bible or Mao Tse-tung’s ‘Little Red Book’, took on enormous political significance.

Today, there is yet another new twist to some of the copying. Governments and corporations have been relentlessly and intrusively compiling secret documents and dossiers on a scale that is mind boggling. But lately, as evidenced by such phenomena as WikiLeaks and Edward Snowden’s whistleblowing, a small but effective movement of computer hackers has turned the tables on the document keepers to make them the document leakers. Huge batches of hitherto secret, private or classified files are now being released en masse to the public, to expose wrongdoing.

The term document used to simply mean an official written proof used as evidence. However, the Dutch documentalist Frits Donker Duyvis (1894–1961), who was a pioneer in information science, nevertheless contended that since a document is the ‘repository of an expressed thought’, its contents have a ‘spiritual character’.

Many of the documents included in this book do seem to possess an aura that can still be felt, decades or even centuries after their creation and following countless reproductions. Maybe this unique human quality shining through is one of the attributes contributing to their power. In some instances that power was used as an instrument of the king, the pope, the state or the corporation, or as a ‘prop’ in the theatre of ruling and policing. The document may have embodied the governmental power to command a specific action, the sacred or artistic power to reach the reader in a profound way, the messianic power to convey a vital message at the right moment, or the power of an inventor to conceive a revolutionary new idea in its simplest form.

All evinced some power to make things happen either now or in the future. To make it so, and in some cases to change the world. Here are 100 of those documents.

Anne Frank’s diary has become the most famous account of life during the Holocaust, read by tens of millions of people (see here).

A page from a Song Dynasty (AD 960–1279) version of the I Ching, complete with scholarly commentary.

I Ching

(2800 BC)

An ancient Chinese manual of divination employs patterns of trigrams and hexagrams, interpreted according to the principles of Yin and Yang, to offer sage guidance about an individual’s present situation and future. Scholars consider it the epitome of Chinese philosophy.

No philosophical work has exerted more influence in Chinese culture over the millennia than the ancient I Ching, the ‘Book of Changes’.

While its origins remain shrouded in legend, some historians trace its evolution back more than 5,000 years to a mythical emperor, Fu-Hsi, followed by other holy men, including King Wên who lived in the Shang dynasty of 1766–1121 BC and his son the Duke of Chou, and later Confucius (Kung Fu-Tze) who lived from 551 to 479 BC. It appears to be the oldest document still in continuous use.

The oldest extant version, consisting of bamboo strips found in Guodian, has been dated to about 300 BC; it is held in the Shanghai Museum. Westerners did not begin to learn of the I Ching’s existence until the 18th century and the first complete publication (in Latin) occurred in Germany in the 1830s. Scholars agree it is a composite work that was frequently copied and revised over the course of many centuries.

The ancient Chinese practice of cleromancy entailed casting lots (usually sticks or stones) to determine divine intent, and the I Ching remains its most sophisticated example. In this case, the divining is done by tossing yarrow stalks or coins, which is called ‘casting the I Ching’. After posing a question and casting, the order they form can be looked up to reveal its cosmological significance. The document offers 64 readings, and each chapter consists of a different six-line hexagram made up of long or short stalks.

The Hsü hexagram, for example, reveals: ‘Hsü intimates that, with the sincerity which is declared in it, there will be brilliant success. With firmness there will be good fortune; and it will be advantageous to cross the great stream.’ This answer is then open to interpretation.

Transformation is the central idea behind the I Ching. All living things change through time and I Ching defines change in terms of Yin and Yang. Yin is negative, dark and feminine; Yang is positive, bright, and masculine. The I Ching professes that all change can be understood in terms of the relationship between the two. When they are in balance, there is harmony.

The I Ching indicates whether a given action will bring good fortune or misfortune, but it is not a fortune-telling book. It provides many basic precepts about life’s vicissitudes such as the following: ‘Before the beginning of great brilliance, there must be chaos. Before a brilliant person begins something great, they must look foolish in the crowd.’

The ancient work also has much to offer in the study of Chinese civilization.

These bamboo sticks date to around 300 BC and are the oldest extant examples of the I Ching.

Code of Hammurabi

(1754 BC)

A French archaeologist in the former Babylon kingdom unearths an artefact that documents the world’s most ancient yet surprisingly advanced legal code. Many of its provisions reflect a deep commitment to justice under the rule of law.

A 2.25-meter-high stele of black basalt in the shape of a large index finger once stood in Babylon for all to see. At the top of the volcanic rock was an engraved depiction of the state’s ruling king, Hammurabi, sitting on his throne, receiving the Mesopotamian god of law, justice and salvation, Shamash. And beneath them, the carvers had inscribed long columns of text on both sides of the stone.

In 1901 a French archaeologist discovered the object in what is now Khuzestan Province, Iran. Conquerors had apparently removed it from Sippar (in present-day Iraq) on the eastern bank of the Euphrates sometime in the 12th century BC. Translation from its ancient Akkadian language revealed that the stone proclaims a comprehensive legal code – the code of Hammurabi – consisting of a lengthy prologue invoking the power of the gods and the king, a long list of laws and an epilogue. ‘LAWS of justice which Hammurabi, the wise king, established,’ the epilogue states. ‘A righteous law, and pious statute did he teach the land. Hammurabi, the protecting king am I.’

Hammurabi, the sixth Babylonian king, was an able administrator who ruled a multi-tribal and multi-ethnic Mesopotamian empire of walled cities, fertile fields and irrigation canals from about 1792 to 1750 BC. His sophisticated code has been dated to about 1754 BC.

Nearly half of these 282 laws deal with issues of liability and other business matters; another third address a range of domestic relations such as paternity, inheritance, adultery and incest. But commercial interests often govern domestic affairs. Marriages, for example, are treated as a business arrangement.

Modern legal scholars are especially interested in the code’s elaborate punishment provisions, as its inclusion of the principle of lex talionis (an eye for an eye) predates Mosaic Law, the Law of Moses, by two centuries or more. The code’s system of scaled punishments adjusts penalties according to grades of slave versus free and other marks of social status.

The penalties are harsh: a total of 28 crimes, ranging from adultery and witchcraft to robbery and murder, warrant the death penalty. Yet King Hammurabi also claims to seek to protect the weak and to foster justice for all his people. Thus one statute establishes that a judge who has handed down an incorrect decision shall be fined and removed from the bench. Others display the earliest known example of the principle of presumption of innocence – a protection that wouldn’t appear in Western legal codes until much later.

The original stele found in 1901 is on display at the Louvre in Paris. Additional stones bearing the code are in other museums as well.

The stele is 2.25 meters tall and depicts a seated King Hammurabi directing Shamash, the Mesopotamian god of law. Beneath this relief are the king’s 282 laws (see detail), which cover 28 crimes that warrant the death penalty, including adultery, witchcraft, robbery and murder.

This 285–250 BC papyrus is the oldest known fragment of The Odyssey. It contains lines from Book 20 that do not appear in standard versions. Other third-century BC examples show that Homer’s texts contained local variations that were subsequently standardized by Alexandrian scholars.

A page from the oldest complete manuscript of The Iliad. Known as Venetus A, this AD 900 version is handwritten on vellum and contains five levels of scholarly annotation.

Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey

(c. 750 BC)

Preserved for 3,000 years by memory, writing, and print, the two greatest epic poems from ancient Greek culture have served for millennia as a pillar of Western literature, leaving scholars to speculate about the genius or geniuses who created these timeless classics.

Plato, writing in 400 BC or so, called Homer ‘the teacher of [all] Greece’. Five hundred years later, the Roman rhetorician Quintilian called him ‘the river from which all literature flows’, and 1,400 years after that the French novelist and stylist Raymond Queneau commented: ‘Every great work of literature is either The Iliad or The Odyssey.’ Yet little is known about the ascribed author, Homer, including his true ancestry and biography, whether he was really blind as ancient historians later claimed, and even when and whether he lived.

What is known is that Homer is credited with having written the two great epic poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey, in about 750 BC, although some modern historians have dated their origins to more than 1,000 years before that and others have suggested different time frames.

The Iliad depicts the siege of Ilion or Troy during the Trojan War, and while the account takes up 24 books, it covers only a few weeks of a long war, offering passages such as, ‘Like cicadas, which sit upon a tree in the forest and pour out their piping voices, so the leaders of Trojans were sitting on the tower.’

The Odyssey focuses on the character Odysseus and his 10-year perilous journey from Troy to Ithaca after the end of the war, also telling what has befallen his family when he was away. ‘Tell me, muse, of the man of many resources who wandered far and wide after he sacked the holy citadel of Troy, and he saw the cities and learned the thoughts of many men, and on the sea he suffered in his heart many woes.’ Composed in 12,110 lines of dactylic hexameter, the poem also features a modern plot.

Most historians believe the works were orally transmitted and performed over a long period, perhaps for centuries, before they were eventually written down, and certainly no first manuscript has survived from 3,000 years ago or more. The oldest known fragments of The Odyssey, written on papyri and discovered in the sarcophagi of mummified Greek Egyptians dated to 285–250 BC, are displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The oldest complete manuscript version of The Iliad, handwritten on vellum and dated to about AD 900, is known as Venetus A, and it has been preserved at the Marciana Library in Venice since the 15th century. Each page contains 25 lines of Homeric text, accompanied by scholia (marginal notations and annotations) which were inscribed by editors in Alexandria sometime between the first century BC and the first century AD. A fine photographic facsimile edition was made in 1901 and scholars have recently completed a greatly improved version using the latest digital imaging technology.

The Art of War

(512 BC)

An ancient Chinese military treatise ranks as the greatest primer ever written on warfare strategy and tactics, providing a timeless and savvy guide for many field generals over the ages; it is also consulted by corporate executives, trial lawyers and other serious competitors.

‘The art of war is of vital importance to the state. It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry which can on no account be neglected.’ So begins history’s greatest published meditation on warfare, the literary origins of which remain in dispute. Some authorities wonder whether it was authored by a fabled Chinese military leader named Sun Tzu or Sunzi, if indeed he really existed; others suggest that the ideas may have been compiled and modified by many hands over a long period. Everyone, however, agrees that the work is very ancient: an archaeological discovery in Shandong in 1972 unearthed a nearly complete bamboo scroll copy, known as the Yinqueshan Han Slips (206 BC–AD 220), which is nearly identical to modern editions of The Art of War.

Considered the greatest of China’s Seven Military Classics, the work was first translated into French in 1772 and partially put into English in 1905, and its readers have long marvelled that the document’s guidance never seems to have become outmoded. Commanders from Napoléon Bonaparte to Generals Võ Nguyên Giáp and Norman Schwarzkopf have credited its teachings for some of their successful military strategies and tactics. In a 2001 TV episode of The Sopranos, the mobster Tony Soprano tells his psychiatrist, ‘Here’s this guy – a Chinese general, wrote this thing 2,400 years ago and most of it still applies today.’

The Art of War consists of 13 chapters. Each grouping offers wise and time-tested instruction on a key aspect of warfare. Written in plain but lucid terms, the text presents basic principles and strategies on when and how to fight, providing cardinal rules such as ‘He will win who knows how to handle both superior and inferior forces’ and ‘He will win whose army is animated by the same spirit throughout all its ranks.’

Sun Tzu considers war a necessary evil to be avoided whenever possible. All wars should be waged swiftly or the army will lose the will to fight and ‘the resources of the State will not be equal to the strain.’ ‘There is no instance of a country having benefitted from prolonged warfare.’ ‘All warfare,’ he writes, ‘is based on deception. Hence, when we are able to attack, we must seem unable; when using our forces, we must appear inactive; when we are near, we must make the enemy believe we are far away; when far away, we must make him believe we are near.’

The text identifies the six main ‘calamities’ that a general might expose his army to: 1. flight; 2. insubordination; 3. collapse; 4. ruin; 5. disorganization; and 6. rout. Conversely, a great general will have the ‘power of estimating the adversary, of controlling the forces of victory, and of shrewdly calculating difficulties, dangers and distances.’

These bamboo strips, known as the Yinqueshan Han Slips, date from 206 BC–AD 220 and are the oldest extant example of the sixth-century BC Art of War text.

An 18th-century bamboo edition of The Art of War commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor (1711–99), the sixth Qing Emperor of China.

This fragment from the Dead Sea Scrolls is taken from The Book of War. Written in Hebrew, it dates to AD 20–30 and tells the story of a 40-year battle between the forces of good and evil.

Dead Sea Scrolls

(408 BC–AD 318)

Discoveries in caves of the Judean Desert yield caches of ancient manuscripts containing some of the earliest known pieces of the Old Testament and other writings from early Hebrew culture. Their ownership and meaning can prove controversial.

In November 1946 a young Bedouin shepherd was searching for a stray amid the limestone cliffs that line the northwestern rim of the Dead Sea, around Qumran in the West Bank, when he came upon a cave in the rocky hillside. Upon casting a stone into the dark entrance, he heard clay pottery breaking, so he ventured inside to investigate. He found several large earthen jars with sealed lids. In them were long objects wrapped in linen – old scrolls covered with writing he couldn’t decipher.

Over the next three months the Arab youth and three companions retrieved and sold seven of the mysterious objects to antiques dealers in Bethlehem without knowing their true value.

When Professor Eliezer Lipa Sukenik of Hebrew University glimpsed what was written on one of the scrolls, he shook with excitement. ‘I looked and looked,’ he later recalled, ‘and I suddenly had the feeling that I was privileged by destiny to gaze upon a Hebrew scroll which had not been read for more than 2,000 years.’

Over the next nine years the number of discoveries in the region grew to more than 900 scrolls and fragments. The writers had scrawled their accounts on animal hide or papyrus, using reed pens and varied brightly coloured inks. Most of the texts are written in Hebrew, with some in Aramaic, Greek, Latin and Arabic.

The collected documents became known as the Dead Sea Scrolls. And they created an international sensation, for several reasons. Because scholars placed their origin at between 408 BC and AD 318 – a crucial moment in the development of monotheistic Judeo-Christian religions – the manuscripts hold great historical, religious and linguistic significance on issues that are often fiercely disputed.

As new technologies have developed, samples of the scrolls have been carbon-14 dated and analysed using DNA testing, X-ray, and Particle Induced X-ray emission testing and other techniques. This indicates that some of the scrolls were created in the third century BC, but most seem to be originals or copies from the first century BC. A large number relate to a particular sectarian community.

The scrolls represent what are probably the earliest known copies of biblical texts, including most of the books of the Old Testament, as well as many additional writings. Together they shed light on the Old Testament’s textual evolution. Findings from the scrolls have leaked out over several decades, yet even today the contents of certain documents have not been publicly revealed and analysed, which has generated even more controversy.

Some of the scrolls are currently on display at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where their ownership and meaning remains hotly contested.

One of the pottery jars found in the caves of Qumran. These lidded clay containers were used for storing the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Mahabharata

(c. 400 BC)

The world’s longest epic poem, which includes Hinduism’s most widely read sacred scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, as one of its seven principal parvas (sections), ranks as one of the greatest literary achievements in history – one of the high points of Indian culture for more than 2,000 years.

Along with the Ramayana, the Mahabharata is one of ancient India’s greatest Sanskrit epics – a saga of such staggering size it takes close to two full weeks to recite, with over 100,000 shloka (couplets) and long prose passages that combine to form a total length of 1.8 million words.

With a title that has been translated as ‘The Great Tale of the Bharata Dynasty’, the core story follows the struggle for the throne of Hastinapur, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan, which is waged by the Pandavas and the Kauravas. It includes innumerable episodes about the role of kings, princes, sages, demons and gods. The deeply philosophical work embodies the ethos of Hinduism and Vedic tradition, recounting much of Indian culture’s sacred history, and is told with a scope and grandeur that dwarfs all other epic works.

Some of the events described in the Mahabharata are supposed to have occurred as far back at 1000 BC, while the oldest extant text has been dated to the eighth or ninth century AD, according to Professor Rajeswari Sunder Rajan of Oxford University, writing in 2000. Teams of scholars have laboured for decades in an effort to ascertain how the document may have evolved to reach its final form between the third and fifth centuries. One research team has gathered and compared many manuscripts of the huge epic to compile a master reference series of 28 volumes.

The Mahabharata is usually attributed to Rishi Vyasa, a revered mythical figure in Hindu traditions who is both an author and a main character in the story. Vyasa says one of his aims is to explain the four purusarthas (goals of life) that lead to happiness, and this deep didactic aspect has made the work the foundational guide to Indian moral philosophy and law.

Some scholars suspect that roots of the epic may lie in actual events that happened several centuries before the Common Era; others accept the work as a compendium of swirling and crisscrossed legends, religious beliefs and semi-historical accounts that nevertheless provide a rich picture of Hindu life and philosophy in ancient India.

All agree it is impossible to prove if or when Vyasa really lived, or to disentangle facts from fiction in the labyrinthine epic, in part because much of Vyasa’s storytelling is recited by his sage disciple, Vaisampayana, and the rich narrative employs an exceedingly complex ‘tale-within-a-tale’ structure which is common to many traditional Indian religious and secular works. A short excerpt conveys its highly embellished style:

Sauti said, Having heard the diverse sacred and wonderful stories which were composed in his Mahabharata by Krishna-Dwaipayana, and which were recited in full by Vaisampayana at the Snake-sacrifice of the high-souled royal sage Janamejaya and in the presence also of that chief of Princes, the son of Parikshit, and having wandered about, visiting many sacred waters and holy shrines, I journeyed to the country venerated by the Dwijas twice-born and called Samantapanchaka where formerly was fought the battle between the children of Kuru and Pandu, and all the chiefs of the land ranged on either side.

These richly illustrated plates from an early 19th-century edition of the Mahabharata capture the cyclical nature of this literary epic. There are no complete copies of the original text, which is thought to have reached its final form by the fifth-century BC.

This brightly coloured 18th-century painting of one of the techniques described in the Kama Sutra is from the Rajput school, which flourished in the royal courts of Rajputana. There are no surviving copies of the original Sanskrit text, which is thought to have been compiled some time between the fifth century BC and the third century AD.

Kama Sutra

(400 BC–AD 200)

Although widely known today as a manual of ingeniously contorted coital positions, the original (and unillustrated) ancient Sanskrit text provides a comprehensive and surprisingly modern guide to living a sensually fulfilling life, in which sexual intercourse is simply one ingredient.

The Sanskrit term kama sutra signifies a guide to sexual pleasure. The ancient literary work of that title is generally attributed to the sage Vatsyayana of northern India, who claims to be a celibate monk, and has compiled all of the accumulated sexual knowledge of the ages through deep meditation and contemplation of the deity; however, its origins are unclear. Written in an archaic form of Sanskrit, the Kama Sutra is the only known philosophical text from that period of ancient Indian history.

Organized into 36 chapters containing 1,250 verses, the work presents itself as a guide to a pleasurable life. Although the central character is a worldly but virtuous male, its guidance about courtship and romance also applies to women, more or less. ‘A man,’ it says,