28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

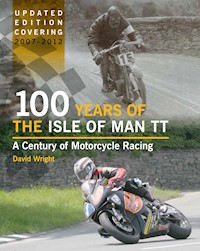

For over 100 years the world's best motorcycle racers have pitted themselves against the gruelling 37-and-threequarter-mile Isle of Man Mountain Course at the annual event known worldwide simply as 'the TT'. The Tourist Trophy meeting - to give its proper name - represents perhaps the greatest challenge that the sport of motorcycle racing can offer. The top names in road racing - Collier, Wood, Duke, Hailwood, Agostini, Hislop, Jefferies, McGuinness, Hutchinson and the Dunlop dynasty - have all considered the pursuit of a Tourist Trophy to be the ultimate goal. From riding the earliest single-cylinder, belt-driven machines with outputs of under 10bhp, to coping with today's sophisticated four-cylinder machines giving well over 200bhp, generations of riders have risked their lives to satisfy the desire to go faster than the next man and to win a TT. In the process they have lifted lap speeds by almost 100mph. Exactly how that huge increase has been achieved is told within these pages, set against the background of the triumphs and the tragedies of the TT history. A comprehensive story of speed at the TT Races, superbly illustrated with over 200 colour photographs and maps.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

DAVID WRIGHT

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2017 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

© David Wright 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 299 1

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

CHAPTER 1 GATHERING MOMENTUM

CHAPTER 2 A SPEEDY DECADE

CHAPTER 3 FAST FOREIGNERS

CHAPTER 4 POST-WAR PROGRESS

CHAPTER 5 EAST vs WEST

CHAPTER 6 TROUBLED TIMES

CHAPTER 7 A NEW ERA

CHAPTER 8 PRODUCTION MACHINES TO THE FORE

CHAPTER 9 A COSTLY BUSINESS

CHAPTER 10 FASTER AND FASTER

CHAPTER 11 ONWARDS AND UPWARDS

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Every year in late May and early June, tens of thousands of people journey to the Isle of Man to be present at an event known the world over simply as ‘The TT’. For two weeks, the roads that make up the 37¾ miles of the famed Isle of Man Mountain Course are given over to top motorcycle racers, to ride the fastest bikes of the day in pursuit of one of the most highly coveted prizes in motorcycle racing: a Tourist Trophy.

This is the way it has been for 110 years, during which time the annual event has evolved from a single race into a festival of motorcycling. But however varied the interests on show, the main reason for the high-octane atmosphere that envelops the Island during those two weeks is the unfettered spectacle of raw speed generated by racing over the public roads of the TT Mountain Course.

It was the opportunity to break free from the shackles of mainland Britain’s then 20mph speed limit and to ride faster than the next man that brought the first motorcycle TT to the Isle of Man in 1907. Recognized from the outset as being one of motorcycling’s greatest challenges, for over a century the island has attracted the very best road racers, while successive generations of followers have crowded the roadside banks and marvelled at the way in which riders have gone ever faster at this unique event.

In the following pages you can read about the attraction of speed to competitors and spectators, and how faster motorcycles have caused the time required to lap the Mountain Course to shrink from 45 minutes to under 17 minutes. Also considered are how changes to the roads and the rules of racing have affected race speeds, plus the many factors in the development of racing motorcycles that have contributed to lap speeds growing from an average of just over 40mph to well in excess of 130mph. All this is interwoven with the history of the event and will leave you in no doubt that it is speed that has shaped most aspects of the now legendary TT races.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A book like this cannot be written without assistance across many areas and I am grateful for the support provided by Stan Basnett, David and Joan Crawford, Ralph Crellin, Tony East, Geoff Judges, Paul Wright, Manx National Heritage and the VMCC Library. The database on www.iomtt.com was consulted on several occasions and found to be very useful.

Photographs to illustrate the theme of ‘Speed’ have been supplied by Stan Basnett, Ron Clark, David and Joan Crawford, Juan Cregeen, John Dalton, Paul Ingham, Alan and Mike Kelly of Mannin Collections, Ray Knight Archives, Brian Maddrell, Doug Peel, Geoff Preece, Richard Radcliffe, Elwyn Roberts, Rob Temple, Paul Wright, Bill Snelling of FoTTofinders and Mortons Media.

The author has made every effort to locate and credit the source of the hundreds of photographs used in the book. If any have not been properly acknowledged, please accept my apologies.

Special thanks go to Vic Bates for providing considerable input to this project, drawing maps of the several TT courses, taking photographs to illustrate riders at particular locations on the course and making his photo archive available for use.

CHAPTER ONE

GATHERING MOMENTUM

Followers of the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy races are interested in many aspects of the annual event, but the dominant attraction to most of them has always been the spectacle of raw and unbridled speed on offer over the roads of the famed and feared Mountain Course. Through successive generations of TT racing, spectators have marvelled as riders have exhibited their skills and courage over those public roads, while extracting maximum performance from their machines. Each will have given their all, but history confirms that it has always been the fastest riders who commanded the most attention, received the greatest publicity and entered the record books.

Much has been written to explain man’s wish to travel ever faster, but just one week after the first TT race in 1907, when the event faced criticism from some quarters, The Motor Cycle magazine neatly summarized the situation with the words: ‘It is useless to say that fast speeds are not to be encouraged, human nature being what it is.’

Top motorcycle racers have always demanded the very best motorcycles to ride and over a century of effort has now been committed to developing more powerful racing engines, together with improved transmissions, suspension, brakes, tyres, electrics and the like, all with the aim of putting better machines into the hands of riders, to travel ever faster around the 37¾-mile lap of the TT Mountain Course. Has all that effort been successful? Well, in the first running of the race for the Tourist Trophy over the Mountain Course in 1911, winner Oliver Godfrey thrilled spectators with speeds they had never before experienced, as he rode his c10bhp Indian to first place at a race average speed of 47.63mph, reaching perhaps 65mph in the process. In 2016 Michael Dunlop did exactly the same with his 220-plus bhp BMW as he rode to victory at a race average speed of 130.68mph, while hitting close to 200mph. That simple comparison reflects over 100 years’ growth in power and speed, substantial technical progress and an awful lot of excitement.

EARLY TT RACES

The first Tourist Trophy race for motorcycles was run in 1907, over ten laps of a 15½-mile circuit in the west of the island called the St John’s Course.

It presented a challenge for motorcycles of the era, for they were still in an early stage of development. Though billed as a race, out and out speed was not the main target of the first event: in words of the day, the Tourist Trophy race was created ‘for the development of the ideal touring motorcycle’. To help achieve that ideal, machines were equipped with silencers, had to carry a specified minimum weight of tools, be fitted with a proper saddle and use touring-type mudguards. The regulation that had most influence on speeds, however, was the one that specified fixed allocations of fuel for the race. This was limited to 1 gallon for every 90 miles of race distance for single-cylinder machines and 1 gallon per 75 miles for those with more than one cylinder. For many competitors the effect of that regulation was to govern the speed at which they could ‘race’, because trying to run at maximum throttle would see them use up their fuel before completion of the 158-mile total distance.

This is the St John’s Course, used from 1907 to 1910.

Riders tackle the sharp downhill turn at Douglas Road Corner, Kirk Michael, on the St John’s Course.

After spending their practice sessions seeking the right balance between speed and economy, twenty-five riders lined up in front of the historic Tynwald Hill at St John’s to start the first TT. As there were no specified standards for riding gear, they turned out in a selection of leather, tweed and oilskins. Wearing additional belts and pouches for spare parts and sometimes a spare inner tube over the shoulder, they probably looked a motley crew, but they were courageous pioneers, for few would have ridden a race that was anything like the one that faced them on 28 May 1907. Dispatched in pairs at one minute intervals, all had to ride with fuel consumption in mind; the amount remaining in each rider’s tank at the end was measured and publicized.

Fastest rider on a twin-cylinder machine in 1907 was Rem Fowler on a Norton. Suitably braced with ‘a glassful of neat brandy tempered with a little milk’ before starting, he returned a race average speed of 36.22mph, set the fastest lap of the day at 42.91mph, and had a petrol consumption figure of 87mpg. Fastest overall and winner of the newly created Tourist Trophy was first man home on a single-cylinder machine, Charlie Collier. On his family-built Matchless, he rode to a race average speed of 38.22mph, with a fastest lap of 41.81mph at 94.5mpg.

Fowler had an eventful race, with delays to progress caused by falling off twice, repairing a front-wheel puncture, changing several sparking plugs, tightening his drive belt twice and fixing a loose mudguard. Such problems were quite usual in early TT races, meaning that competitors needed to have mechanical skills as well as riding ones. In contrast to the many difficulties experienced by Fowler, overall winner Collier had a relatively trouble-free run during the 4 hours, 8 minutes and 8 seconds it took him to complete the first race for the magnificent silver Tourist Trophy, a gift to the organizers from the Marquis de Mouzilly St Mars.

The motorcycles used in 1907 were still recognizably derived from pedal cycles but they were not easy to control. While trying to race at speed over poor road surfaces, riders had to juggle levers to achieve the right balance between mixture strength, spark timing and throttle opening, whilst also remembering to top up the drip-fed total-loss lubrication system by operating a manual oil pump at regular intervals. The bikes were tall with wide handlebars, had virtually no springing and possessed only poor brakes. Tyres were of a narrow 2¼-inch beaded-edge section and were inflated to high pressures to help them grip the rims. Most lacked any form of clutch or gearbox, so the single gear chosen had to be a compromise between gaining the best speed on the flat while retaining the ability to climb hills and negotiate sharp bends. The direct drive from engine to rear wheel was usually by leather belt. As races ran over roads littered with horseshoe nails and sharp stones, punctures were frequent. Top speed was said to be about 65mph.

Ready for the fray prior to the 1908 TT, Captain Sir Robert Keith Arbuthnot, Bt, shows off his Triumph, a typical machine of the day.

Confirming that speed was important to all who took part in the first TT, the Triumph Engineering Company Ltd’s post-race advertising claimed that ‘The Triumph made faster time than any machine in the race after deducting time lost for repairing punctures’. However, the Norton Manufacturing Company Ltd countered with an advertisement saying ‘The fastest machine in the Tourist Trophy was the Norton twin, in spite of misleading statements to the contrary’.

GETTING FASTER

Pedals, previously used for starting and to aid hill-climbing, were banned for 1908. That had little effect on race speeds, but the elimination in 1909 of the fixed petrol allowance and the freedom given to run without silencers certainly did, because it allowed for full throttle all the way, where machine and road conditions allowed. This meant that as well as meeting the need for speed, riders could satisfy another aspect of human nature – trying to defeat their fellow riders. As a result, Harry Collier (brother of 1907 winner Charlie) brought his Matchless home in a time almost 25 per cent faster than previous winners, pushing the race average speed up to 49.01mph and setting the fastest lap of 52.27mph. That was a huge increase from the previous fastest lap of 42.91mph and provided an early example of how rule changes can impact on race speeds.

Ballacraine was approached from the opposite direction in the early TT races. In 1910 the organizers ramped the outside of the corner to help the single-speed machines maintain momentum for the climb that followed up to Ballaspur. Not everyone got it right and there were spills. However, a doctor from Peel was on hand and his car can be seen here, parked on the course and with the handles of a stretcher sticking out of the window.

The speeds achieved in 1909 may not sound fast to current TT fans, but they would have impressed those who saw and read about them. The maximum speed allowed on the roads of Britain at the time was 20mph (14mph on the Isle of Man), and with a low level of vehicle ownership, few people had any experience of what it was like to travel at 60-plus mph. They would have been in justifiable awe of those early racers.

A force to be reckoned with in the early years of TT racing, past winners Charlie and Harry Collier took their Matchless machines to first and second places at the 1910 TT, although it was Harry Bowen on his BAT who set the fastest lap at 53.15mph, in what turned out to be the last TT to be run over the St John’s Course.

1911: THE MOUNTAIN COURSE

The Isle of Man Tourist Trophy races were organized by the Auto Cycle Union (ACU), who governed motorcycle sport in most of Britain. In a deliberate attempt to hasten motorcycle development, in particular to advance the adoption of variable gears, it moved the races from the St John’s Course to the far more demanding Mountain Course in 1911. No one could have realized what a profound effect that move would have on motorcycle development over the next 100 years, for the Mountain Course became a test-bed for almost every new design feature, with manufacturers confident that if a new development could withstand the rigours of a TT race, then it was fit to market to the general public.

Early TT meetings comprised just a single race, with classes for single- and multi-cylinder machines. But in 1911 two separate races were run, carrying the titles of Senior and Junior, in which singles and multis raced each other. The multis (almost exclusively twins) were permitted to run with a greater engine capacity; for the Senior they had an upper limit of 585cc with singles limited to 500cc, while in the Junior, twins could be up to 340cc and singles 300cc. Race distances were five laps and 187½ miles for Seniors and four laps covering 150 miles for Juniors.

Machines entered for the smaller class were considered ‘Lightweights’ of the day and some manufacturers wanted to retain pedals for the race. However, determined to spur on the development of smaller machines, the ACU refused their request. Meanwhile, as has always been the case with the Tourist Trophy meeting, other people had ideas on how the event should be run, with the motorcycle press floating the notion of a minimum weight limit for riders because they believed that those of small stature would gain an unfair advantage on the climb of the Mountain. Indeed, their proposal was that any rider weighing less than 140–150lb (63–68kg) in full riding gear should be barred from the event. There were dissenting voices on other aspects, too; for example, not everyone agreed with moving the TT to the Mountain Course. There were claims that the descent from Snaefell would be dangerous, even though the real concern for most was the 1,400ft (430m) ascent of ‘the Mountain’, particularly as the iron engines of the day were known to lose power when hot.

The route of the TT Mountain Course.

When first used for motorcycles in 1911, the Mountain Course over Snaefell (Snow Mountain) was 37½ miles long and its route was almost the same as today’s, except that on the outskirts of Douglas at Cronk ny Mona, riders turned right and rode through Willaston to reach the top of Bray Hill, rather than going via Signpost Corner, Governor’s Bridge and the Glencrutchery Road as they do today. The start and finish were located on a flat stretch of road after the bottom of Bray Hill before it commenced its descent to the Quarter Bridge.

On the approach to that first 1911 Mountain Course TT it became clear that most manufacturers had accepted the need for variable gears and examples of most of the available types could be seen. A report of the time told of ‘compound and epicyclic gears in the back hub and on the engine-shaft, counter-shaft gears, and direct gears by means of expanding engine pulleys with and without the rear wheel moving in unison to maintain the correct tension of the belt’.

Among manufacturers taking on the challenge of the new course were Triumph, Rex, Scott, Indian, Matchless, Humber, Forward, Norton, Zenith, Premier, Singer and Rudge-Whitworth. Most claimed they were running standard catalogue models, but there was already a recognition of the benefit to sales from winning a TT, with much time and effort put into the preparation of the machines entered. Those who saw the insides of factory-prepared motorcycles told of components polished to a mirror finish while, to cope with the bumpy, potholed course, there was additional brazing, much use of split pins and binding with insulating tape.

SPEEDS

No one really knew what race speeds would be achieved over the new course in 1911. There were pre-race reports that the fancied Oliver Godfrey had been timed at 80mph on an Indian at Brooklands, but he was probably riding a bike that was larger than the 585cc limit set for twin-cylinder machines at the TT. In addition, the poor road surfaces on the island would certainly reduce maximum speed from that achieved at Brooklands’ concrete bowl. Another report told how past winners the Collier brothers had their TT machines ready in good time, and Charlie was said to have reached 68mph on the road, with his new expanding and contracting engine pulley giving ratios of between 3:1 to 5:1. Of the ‘Lightweights’ in the Junior race, it was predicted that a few would reach 55mph and many 50mph, perhaps faster downhill. Meanwhile, the Isle of Man authorities had been debating whether to increase the island’s overall speed limit from 14 to 20mph, but faced with difficulties of enforcing either figure, it voted to abolish the limit instead.

Pre-practice reports on the condition of the roads were not encouraging but have to be judged by standards of the time, for the surfaces were still ‘unmade’, being of rolled macadam with no tar binding. It was clear from the first lap of practice that the section from Ginger Hall to Ramsey was in very poor condition, as was the Mountain Road, which was strewn with loose stones and was described by The Isle of Man Weekly Times as ‘dreadful’. The same newspaper urged that Bray Hill be swept before riders tackled it at what it said would be 70mph.

Practice sessions were all early morning and started from the Quarter Bridge on the outskirts of Douglas. Perhaps seeking to minimize disturbance to local inhabitants around the course, the ACU decreed that practice would be allowed for just one week prior to racing in 1911. However, after representations from the traders and hoteliers of Douglas, who sought to maximize income from the TT, this was extended to two weeks of practice, all of which took place over open roads. That decision to extend the practice period was an early example of peripheral commercial interests influencing the running of the TT, as they do to this day.

Bray Hill in Douglas, just a few years before use in the first Mountain Course TT in 1911.

Winner of the 1911 Junior TT, Percy Evans (Humber), takes a tight line at the tricky Ramsey Hairpin.

Given the conditions in the first year of using the Mountain Course, it is not surprising that there were accidents to riders during practice and, regrettably, the TT saw its first fatality when Victor Surridge fell from his Rudge at Glen Helen.

Both the Junior and Senior TT races of 1911 were held in dry weather, with the former run on Friday, 30 June with thirty-seven entries over four laps, and the latter on Monday, 3 July with sixty-seven entries over five laps. The man who rode to victory in the 150-mile Junior TT was Percy Evans on a twin-cylinder Humber with belt drive and three-speed hub gear. He averaged 41.45mph and set the fastest lap of 42.00mph, finishing well ahead of Harry Collier (Matchless) in second place.

Racing bikes of the day generally ran with small-bore, straight-through exhausts, which gave them a crackling note. Riders would also have been able to hear a regular slap-slap from their belt drives, sundry clickings from the exposed valve gear and usually a loud knocking from the engine when it was put under load at low revs.

DISQUALIFICATION

In the 1911 Senior race, the two most fancied runners, Charlie Collier and French-Canadian ace Jake de Rosier, battled closely for the lead on the first few laps, until de Rosier fell at Kerromoar. Limping in to what was then named the Ramsey Depot (what we now call the Pits, of which there was another at Braddan Church), de Rosier borrowed tools to fix his Indian and, although he rode on to the finish, he was disqualified for what the organizers classed as ‘receiving outside assistance’.

Jake de Rosier urges his Indian through Stella Maris as he leaves Ramsey to commence the Mountain climb in 1911.

Meanwhile, Collier and his twin-cylinder JAP-engined Matchless were eventually beaten into second place by Oliver Godfrey on his two-speed, chain-driven, twin-cylinder Indian. The latter’s average race speed was 47.63mph, while the fastest lap went to Frank Philipp (Scott) at 50.11mph. Thus the 1911 event established the first race average speeds and fastest lap speeds for the Mountain Course, so offering a target for future years and causing one publication to speculate ‘is a 60mph or even a 70mph TT possible in the future?’.

Mention has been made of Jake de Rosier’s disqualification and, although Charlie Collier was initially credited with second place, he too was disqualified. In his case it was for taking on fuel at other than the authorized depots at Ramsey and Braddan.

De Rosier was probably the top racer in North America at the time while Collier held a similar position in Britain, so the serious penalties incurred by those star riders showed how important it was to be fully prepared for a TT race – in all respects. De Rosier’s Indian would undoubtedly have received the most careful mechanical preparation, but failure to secure his tool-bag properly meant that he lost tools during the race and thus had to borrow some when he stopped at Ramsey, so leading to his disqualification. Quite how past-winner Collier managed to miscalculate on fuel and thus be forced to borrow some at Ballacraine is not known, for he was such an experienced racer. However, it is worth mentioning that the TT was still the only race of its kind run in Britain. Collier had taken part in point-to-point road races on the Continent, but in Britain his only opportunities to race were on some of the larger boarded cycle-tracks, in relatively short hill-climbs, at the concrete speed bowl of Brooklands, or, if he had chosen to, in the occasional sand race.

Both of the 1911 races provided victories for twin-cylinder machines, and the fact that they were fitted with variable speed gearing was no doubt to the satisfaction of the organizing ACU. Yet while the event as a whole was considered a success, and manufacturers learned valuable lessons from it, many of them were far from happy with the still young Isle of Man Tourist Trophy meeting.

The intrepid Charlie Collier speeds over Ballig Bridge on his Matchless.

The Continental Tyre and Rubber Co. (GB) Ltd advertised the successful use of its products by Junior and Senior winners of 1911.

1912: DISCONTENT

Soon after the 1911 TT, manufacturers voiced their displeasure with the event. Many and varied complaints were aired: that the Mountain Course was dangerous, that they did not like twin- and single-cylinder machines competing in the same race, that the original concept of using touring machines was being lost, that it was expensive to take part in, that it interrupted production at their factories, to name but a few. Given the concerted nature of these complaints, it seems that these were not just the usual gripes from bad losers but real concerns. Such was the strength of their feelings that the majority signed a bond not to take part in 1912, with a financial penalty falling on anyone who broke its terms.

Not all manufacturers were party to that bond, The Scott Motorcycle Company and H. Collier & Sons Ltd (makers of Matchless machines) being amongst those who refused to sign, but it left the ACU to run an event that would be mostly made up of private runners. Having previously relied on the entry fees and voluntary contributions from manufacturers to help fund the running of the event, this was a real blow to the ACU and could easily have finished the TT after just one year’s running on the Mountain Course. To its credit, the ACU decided to take the financial risk and go ahead with the 1912 races.

Sales of motorcycles were booming and in a crowded market, with little other than the views expressed in the few motorcycling magazines of the day to go on, the buying public still looked for honest pointers as to which machines to buy. TT results could help provide those pointers.

A FRENCH TT?

Even today the Isle of Man TT races cannot be run without the annual approval of Tynwald, the Manx government, and the ACU were kept waiting for that approval for the 1912 races. Perhaps in an attempt to provoke a decision, the motorcycle press wrote about how easy it was to get permission to run road races in France and that, for many, it would actually be simpler to get there rather than to the Isle of Man! This notion began to build momentum and even found support in the French motorcycle press. In January 1912 the ACU decided to write to the Manx authorities and press for a decision. If an early response was not forthcoming, it resolved ‘to communicate with one of the principal French motorcycle clubs with a view to holding this important event in France’. Tynwald’s approval was received before the end of the month.

REDUCED ENTRIES

Come the closing date for entries to the 1912 TT and those for the Senior totalled forty-nine, while for the Junior it was twenty-six. Comparative figures from 1911 were sixty-seven and thirty-seven, showing the effect of the manufacturers’ boycott. Sadly, racing had taken its toll on some of the previous year’s top Indian riders, for Jake de Rosier was lying badly injured in a Los Angeles hospital, while Moorhouse (third in 1911) had been killed at Brooklands. The danger of practising on open roads, as all TT sessions were, was brought home to riders after John Gibson, ‘travelling down Bray Hill at a good speed’, collided with a car that backed out of a side road into his path. Gibson survived the crash, but was injured.

There was nothing radically new in design-wise for the machines entered for 1912, but one important change to the regulations saw the upper capacity limit for the Senior race set at 500cc and for the Junior 350cc. This meant that, for the first time, single- and twin-cylinder engines would compete on level terms in each race. Entrants in the Senior were chasing a first prize of £40 and for the Junior it was £30. In addition, gold medals were awarded to the winners and to any other rider finishing within 30 minutes of the winner’s overall race time.

Course conditions in 1912 were much the same as in previous years, although the island had gained its first stretch of tar-sprayed macadam on the short straight between Quarter Bridge and Braddan Bridge on the outskirts of Douglas. Quarter Bridge itself had been widened considerably, as had the Hall Caine bends, which were now described as ‘all out’. Hall Caine was a renowned author who lived some 6 miles from the start at Greeba Castle, which is how those bends are known today.

WET

It was difficult to gain real pointers to riders’ form during practice in 1912, for several of the sessions were affected by rain, making the roads muddy and riding conditions difficult. Come race day, riders in the Junior faced torrential rain at the start of their race, which eased and then stopped on the second lap.

Very wet conditions at Quarter Bridge for Harry Bashall (Douglas) in the Junior TT of 1912.

This was the first TT to be held under really wet conditions, and as well as affecting the course, it offered a challenge to the waterproofing of magnetos and plug leads. Unfortunately, some machines were found wanting in those areas, leading to early retirements. To add to rider difficulties, the exposed belt drives used by most machines were prone to slip when coated with road mud and this had the effect of reducing speed, particularly on hills.

Fastest man proved to be Harry Bashall on his Douglas; as an indication of the difficult conditions, he stopped eight times during the race to give attention to his machine. Bashall’s race average speed was 39.65mph, which was a commendable figure when compared with the previous year’s winning average speed of 41.45mph in the dry. Fastest lap was by second-placed man Eric Kickham, also on a Douglas, at 41.76mph. There were just eleven finishers out of twenty-one starters.

SINGLES OR TWINS

At the previous year’s TT, twin-cylinder machines had a capacity advantage over the singles and were victorious in both races. The question for 1912 was how would twins fare against singles now that they were on equal capacity terms. By taking the first two places in the Junior race, the Douglas concern showed that twins were still front runners, but how would the big bikes do?

Conditions for the Senior TT held on Monday, 1 July were better than for the previous Friday’s Junior race, although there was rain before the start, the wind was strong and there was some mist over the Mountain, where wandering sheep were said to be troublesome. Riders were despatched singly at one-minute intervals. Pace-setters in the early stages of the Senior were team mates Frank Philipp and Frank Applebee on their twin-cylinder, two-stroke, water-cooled, two-speed, chain-driven Scotts. They were hoping to keep an assortment of single- and twin-cylinder machines at bay over the five laps and 187½ miles of race distance. The pair maintained their lead positions until the fourth lap, when Philipp suffered tyre troubles, leaving Applebee to take victory and be followed home by James Haswell on his single-cylinder Triumph, with Harry and Charlie Collier third and fourth on their Matchless twins. So two cylinders were again victorious over one, but with the first six places in the Senior TT evenly distributed between singles and twins, it appeared that the ACU had got it right by equalizing capacities for 1912.

Frank Applebee and his Scott trying hard at Kate’s Cottage during his winning ride in the 1912 Senior TT.

The 1912 Senior race did not create any records, but given the conditions, Frank Applebee’s race average speed of 48.69mph and fastest lap of the race at 49.44mph were to be admired.

Summarizing a TT race in a couple of paragraphs gives no real hint of the thrills, spills and endeavour involved. The picture here shows how Frank Applebee had to ride to achieve victory and most others would also have been on their personal limits. Not everyone made the finish and the post-race reports tell of falls, valve troubles, fuel difficulties, fires, punctures and failure of other components.

DRIVE BELTS

These were mostly of leather, one reason being that it had plenty of give’ and was thus able to cushion some of the shocks imposed by each firing stroke. Prone to slip in wet and muddy conditions, belts also had a tendency to stretch and to snap their fastening links. Riders carried repair kits to deal with such problems.

While chain drives tended to stretch less than belts, most riders liked to subject new chains to a lap of the course before using them in a race, thus taking out some of the stretch. Once stretched, a metal chain stayed stretched. Users of leather belts also liked to stretch them before a race and having done so they would remove them from the machine and hang them up with a substantial weight attached. This was to preserve the stretch, for leather would gradually shrink back towards its original length when not loaded.

BRAKING

Earlier mention was made of drive belts slipping under muddy conditions. This was mostly due to mud getting on the dummy rim of the rear wheel, which the belt was trying to drive, and on the engine pulley. That dummy rim, sometimes called the belt rim, was also used for the basic slowing process, a block of friction material being pressed against it by operation of a brake pedal. Again, mud on the dummy rim reduced braking effect, just adding to the difficulty of racing in the wet. With the same tyres used in all weathers, poor conditions also increased the danger of losing adhesion and creating what riders of the day called ‘sideslip’.

Typical rear-wheel arrangement showing the dummy rim and multi-link leather drive belt. The basic rear brake is also visible.

Machines were fitted with two brakes, the second usually being of the horseshoe or stirrup shape that utilized two brake blocks bearing against the wheel rim – like the pedal cycles of the time – and could be on either the front or back wheel. It was a time when riders were cautious about using the front brake, but even when used together, the brakes offered limited stopping power to reduce speed for corners, or to control the descent to Creg ny Baa, which was described as ‘the sharpest pull-up on the course’. Brakes of the time were not progressive in action, having a tendency to ‘grab’ and induce skidding, but some must have been better than others, for a report from the 1912 Senior race observed: ‘the Triumph riders approached the bends much faster than the majority, relying absolutely on the efficiency of their brakes in the last 50 yards to steady their breakneck speed’.

In addition to using their brakes, riders sought to aid the slowing process by making use of the valve-lifter on the approach to corners. By pulling a lever they lifted the exhaust valve off its seat and broke the seal to the combustion chamber. This largely negated the effect of the firing stroke and thus reduced drive. As they rounded the corner, the lever would be released and the exhaust-valve would revert to normal operation.

1913: ENDURANCE

Early TT races were a test of endurance and Frank Applebee had to ride for almost 4 hours to take victory in the five-lap Senior TT of 1912, with lesser riders in the saddle for much longer; some had to be helped from their machines at the finish. In a continuing quest to push motorcycle development and reliability, the TT organizers shocked everyone when they announced that the Senior TT of 1913 would be over seven laps and the Junior over six. Fortunately, they recognized the extreme demands this would put on riders and so split each race into two sessions. Two laps of the Junior were run on the Wednesday morning, after which the machines were locked away under ACU control and the Senior runners did three laps. After a day’s rest, the riders then rode their remaining four laps on Friday. The event had recovered its popularity with manufacturers by 1913 and those that were left from a combined original entry of 148 rode together on the Friday, with Seniors identified by red waistcoats and Juniors wearing blue.

Overall victory in the 1913 Junior TT went to Hugh Mason (NUT-JAP), who despite spending most of the previous week in hospital after a practice crash, lifted the average race speed to 43.75mph and set the fastest lap of 45.42mph. As in 1912, Senior victory went to a two-stroke Scott, this time with ‘Tim’ (H.O.) Wood aboard. His race average was fractionally less than Applebee’s in 1912, but he broke Godfrey’s lap record from 1911, increasing it from 50.11mph to 52.12mph, in noticeably better riding weather. Spectators, and most of those who read about the races, were pleased to see the lap record broken by a handsome 4 per cent, but it induced a magazine of the day to publish an article titled ‘Slowing Down the Senior Tourist Trophy’. Interestingly, a read of the article revealed that while the title was a recognition of some peoples’ views, the writer was of the opinion that, ‘figures seem to show that the limits of speed fixed by the roads and by the engine dimensions have already been reached in the Senior event’.

W.F. Newsome took second place in the 1913 Junior TT on his Douglas, after racing for 5 hours, 9 minutes and 20 seconds. He rode a Rover in the Senior race and Bicycling News and Motor Review wrote: ‘He sustained a badly-gashed tyre two miles from the depot; he walked and ran there, obtained a new cover, and ran and walked back, fitted the tyre, and finished – enabling the Rover team to win the team prize’.

1914: NEW FACES

For the 1914 races, the start was moved to the top of Bray Hill, where temporary pits, grandstand and scoreboards were erected. It was a year when crash helmets became compulsory for the record entry of 159 and one where two new marques joined the list of TT winners, as Eric Williams took an AJS to race and lap records in the Junior and Cyril Pullin piloted a Rudge to record-breaking victory in the Senior. Tim Wood (Scott) was credited with the fastest lap in the Senior, breaking his own record from 1913, with a speed of 53.50mph and, in an unusual occurrence, past winner Oliver Godfrey (Indian) tied for second place with newcomer Howard Davies (Sunbeam). TT watchers noted that both victories in 1914 went to single-cylinder machines. This was a contrast to previous years, when twin-cylinder machines had prevailed, although the fastest lap and second places by Wood and Godfrey on twins showed they were still a force to be reckoned with.

HANDLING

A recurring theme at the TT during the years running up to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 was that although manufacturers were increasing engine outputs and thus, in theory, speeds, the poor road conditions meant that riders were unable to use the full 10–12bhp available to them. Those who studied the handling of machines over the potholed and loose surfaced roads met with in TT racing could see that some makes handled better than others. This resulted in greater attention being given to frame and fork design, to improve handling and allow riders to travel marginally faster over the poor roads. It was an early lesson for manufacturers – which would be repeated many times over the next century – that engine power over the TT Mountain Course counted for little without comparable road-holding.

In 1914 the start was moved to the top of Bray Hill, where Eric Williams (AJS) is shown finishing the Junior race.

SPEED SELLS

Whether the phrase ‘Speed Sells’ was in use in the early days is not clear, but manufacturers were certainly aware that speed was a plus factor and used it in their advertising. Many of them added a ‘TT Model’ to their catalogues, aimed at buyers who desired a machine resembling a racer, with slightly downturned handlebars, sometimes a little engine tuning and usually a premium on the purchase price. Not all such machines would have been from manufacturers who had actually contested the TT, but a report told that by 1914: ‘It is the exception to peruse a catalogue which does not list a TT model’. However, another report described most manufacturers’ TT models as: ‘merely his standard mount masquerading under false colours’.

Despite the general wish to go faster, the poor road conditions over the Mountain Course limited the growth in TT lap speed in the period 1911–1914 to just over 3mph, going from 50.11mph to 53.50mph.

Soon after the 1914 TT the development of racing motorcycles was put on hold, as major nations spent four years fighting the First World War. Indeed, it was to be six years before racing for a Tourist Trophy returned to the Isle of Man.

Norton pushed the Speed theme in this advertisement for its ‘TT Model’.

CHAPTER TWO

A SPEEDY DECADE

When the First World War ended in November 1918, manufacturers gave priority to the production of motorcycles for road use, so racing had to wait its turn. It was the summer of 1920 before the sound of racing motorcycles once again reverberated around the Mountain Course.

DEVELOPMENT

The concentrated efforts put into war usually accelerate development in specific areas and 1914–18 saw considerable advances in aero-engine design, often on a no-expense-spared basis. With similarities in the performance needs of aero and motorcycle engines, such as light weight combined with low fuel consumption, high output, reliability, accessibility and so on, there was speculation on how post-war motorcycles might benefit from wartime advances in aero-engineering. Surprisingly, the answer given by some well-regarded names was along the lines of ‘not a lot’. James Norton, of Norton Motorcycles Ltd, explained that ‘aero production methods could not be applied profitably to the motorcycle industry’, while George Stevens of A.J. Stevens & Co. Ltd, makers of AJS, opined: ‘I cannot say that the experience gained during the war has helped manufacturers in the matter of improved general design, but it will undoubtedly result in better and improved methods of construction.’

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!