9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

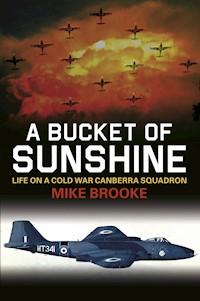

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

A Bucket of Sunshine – a term coined by RAF aircrew for the nuclear bomb that their aircraft would be armed with - is a first-hand insight into life in the mid-1960s on a RAF Canberra nuclear-armed squadron in West Germany, on the frontline in the Cold War. The English-Electric Canberra was a first-generation jet-powered light bomber manufactured in large numbers in the 1950s. The Canberra B(I)8, low-level interdictor version was used by RAF Germany squadrons at the height of the Cold War. Mike Brooke describes not only the technical aspect of the aircraft and its nuclear and conventional roles and weapons, but also the low-level flying that went with the job of being ready to go to war at less than three minutes' notice. Brooke tells his story warts and all, with many amusing overtones, in what was an extremely serious business when the world was standing on the brink of nuclear conflict.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

A DEDICATION

Flight Lieutenant Geoff Trott, RAF

This book is dedicated to the memory of my directional and positional consultant, good friend and close companion from the Cold War days, described in this book. Geoff Trott was a talented, accomplished and professional navigator. His calmness, ready wit and dry sense of humour were a constant support and delight to me during good times and not so good. Geoff was not a career officer and was all the more good company for that. Indeed he was a member of the ‘Supplementary List’ club, whose badge was a ladder with all but the bottom rung broken! Geoff enjoyed his rugby, sailing and beer and loved his family above all other things.

In 1996 Geoff died far too young, of cancer, at the age of fifty-three. He had just retired from the RAF after a career that had seen him rise to the top of the Search and Rescue specialisation. He is pictured above during his first SAR tour flying Westland Whirlwinds from RAF Brawdy in his home nation of Wales. Note the prominence of the crossed keys of his No.16 Squadron badge! Geoff was married to Sonia for thirty-one years and they had two lovely girls, Nicola and Joanna. Sonia also died too young, again of cancer, ten years after Geoff. I am grateful to Nicky and Jan for their permission to make this dedication and for the photograph that they allowed me to use.

A group of us at RAF Idris after a morning’s flying. Geoff Trott is extreme left, with the author on the right. The folically challenged officer in uniform is Squadron Leader Suren. (Gp Capt Tom Eeles RAF (Ret.))

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to acknowledge the part my youngest brother, Richard, played in the conception of this book. Although he was not able to follow me and join the RAF as aircrew, due to colour blindness, he has maintained a lifelong interest in and love of aviation. It was he who, over lunch one day, suggested that I write down all the stories I used to regale him with. It was also Richard who told me that there were precious few books about the RAF’s role in the Cold War, let alone an insider’s view of life on a front-line strike/attack squadron based in Germany.

I would also like to thank my wife Linda, who has stoically put up with my long disappearances into the study and my mental retreats to the 1960s. Not only that but she was my constant proof-reader and critic. Her knowledge and practice as a teacher of the English language and her experience as an avid reader have had more than a significant impact on the readability of this book.

My mother, who is a nonagenarian and living with us, was also but perhaps less critically, another sounding board for my tale. I also want to acknowledge her, and my late father’s, support and guidance during my childhood and those early years when I left home to fulfil my desire to fly.

I want to thank my commissioning editors, Jay Slater and Amy Rigg, also Emily Locke and all the team at The History Press for their help, guidance and support in my first venture into the publishing world. I hope that you agree with me that they have done a fine job in the production of this book.

In addition, I would like to thank Mach One Publications for allowing me to reproduce a section of the Pilot’s Notes Canberra B(I) Mk8 as an appendix in this book.

Unless otherwise credited, all pictures are from my own collection. The Canberra on the front cover came to me via Patrick Camp and Bob McLeod.

Mike Brooke

Normandy, 2011

CONTENTS

Title

A Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Prologue

1 Baptism of Air

2 Apprenticeship

3 Learning the Basics

4 Climbing Higher

5 The Canberra

6 Operational Conversion

7 To Germany

8 The Squadron

9 The Interdictor

10 Finding Our Way Around

11 Learning to Throw Bombs

12 Gibraltar

13 Libya

14 All in a Day’s Work

15 Playtime

16 The Bucket of Sunshine

17 Quick Reaction Alert

18 Surviving and Evading

19 Huntin’, Shootin’ and Dive Bombin’

20 The Squadron Goes Into Battle

21 NATO Exercises

22 Rivalry and Helping Out

23 Visits To and From Friends

24 Picking Oranges

25 What’s the Weather Going to be Like?

26 Air Displays

27 Aden

28 When Things Go Wrong

29 New Buckets

30 TACEVAL

31 Testing Times

32 Moving On with Reflections

Epilogue

Appendix Pilot’s Notes Canberra B(I) Mk8

Plates

Copyright

Introduction

Wing Commander Michael C. BROOKE, AFC RAF(Ret)

Mike Brooke was born in Bradford, West Yorkshire on 22 April 1944. After a grammar school education he joined the RAF as a trainee pilot in January 1962. Subsequent to passing through all-jet flying training he was posted to No.16 Squadron in RAF Germany, where he flew the Canberra B(I)8 in the low-level, night interdictor, strike and attack roles.

On completion of this tour he was selected for the RAF Central Flying School course where he was trained as a qualified flying instructor. Three flying instructional tours followed, then, in 1975, Mike attended the Empire Test Pilot’s School (ETPS) and graduated as a fixed wing test pilot. After graduation he spent five years as an experimental test pilot at the Royal Aerospace establishments at Farnborough and Bedford, at the latter commanding the Radar Research Squadron. At the beginning of 1981 Mike returned to ETPS as a tutor, where he spent three years teaching pilots from all over the world to be test pilots. In 1984 Mike was awarded the Air Force Cross (AFC) for his work within the flight test community; HM Queen Elizabeth II presented the medal to him at Buckingham Palace in November that year.

After attending the RAF Staff College’s Advanced Staff Course he spent six months at HQ Strike Command, where he was a member of the Command Briefing Team. In 1985 Mike was promoted to Wing Commander and given command of Flying Wing at RAE Farnborough. A wide variety of aircraft came his way, including helicopters such as the Gazelle, Wessex and Sea King. After three years at Farnborough, he returned once more to Boscombe Down, this time as Wing Commander Flying, in charge of all flying support activities and deputy to the chief test pilot.

The end of Mike’s RAF career came in 1994, when he decided, at the age of fifty, to take voluntary redundancy. He then spent five years in part-time aviation consultancy, working as a test pilot instructor with the International Test Pilots’ School and Cranfield University, and as a developmental test pilot for the Slingsby Aircraft Company.

In 1998, Mike moved to Texas to fly for a company called Grace Aire, who aimed to give flight test training in their ex-RAF Hunter jet trainers, gain US Department of Defense flight test contracts and display the Hunter at Air Shows. Sadly, the company went into liquidation after two years so Mike returned to Europe, choosing to live in northern France.

In January 2002, he returned to RAF service as a full-time reservist pilot, commanding one of the RAF’s eleven Air Experience Flights, which give flying experience to members of the UK’s Air Cadet organisation. He finally retired from the RAF in April 2004, on his sixtieth birthday. Mike has flown over 7,500 hours (mostly one at a time) on over 130 aircraft types, was a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society, a Liveryman and a Master Pilot of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators, is a Freeman of the City of London and is a Fellow of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. He also flew many historic and vintage aircraft with the Shuttleworth Collection, the Harvard Team and Jet Heritage.

This book is a sometimes irreverent and mostly humorous insight into life on an RAF squadron on the front-line of the Cold War in the mid-1960s. It describes in detail the aircraft, the Canberra B(I)8, and its nuclear and conventional roles and weapons and the flying that went with them. Mike tells his story, warts and all, with amusing overtones in what was an extremely serious business, when the world was standing on the brink of nuclear conflict with its potentially catastrophic outcome for the whole world.

Mike is married to Linda; they have four children and seven grandchildren. They live in France where they have restored a 230-year-old Normandy farmhouse and created a garden from a field. Mike is a licensed lay minister in the local Anglican church, which he and Linda helped to found in 2003. Linda is following in his footsteps and training for the lay ministry in the same church.

Prologue

It is the summer of 1960. I am sixteen years old and I am fishing, sitting on the banks of the River Ouse in Yorkshire, not far from the RAF flying training base at Linton-on-Ouse. I can hear the distinctive whistling of the de Havilland Vampires as they fly their training missions. I know Linton quite well because on many weekends I hitchhike or take a bus there as a Staff Cadet at the RAF Volunteer Reserve Gliding School.

I have flown solo in a glider on several occasions and am about to be sent to Somerset to do an advanced gliding course, where I will learn to soar; that’s stay up a bit longer than the 5 minutes that’s usually the case in the Vale of York.

Suddenly, there is a noise off to my right; it is an ascending, rushing noise. I look in that direction. Round the bend of the river, at what seems only tree-top height, banking sharply, is a Hawker Hunter – the RAF’s premier single-seat day-fighter. No sooner have I taken this in than a second one appears, in a loose trail position, echoing exactly the movements of the first as they rapidly reverse the bank angle to follow the course of the River Ouse. They pass me almost seemingly within touching distance; I can see clearly the silver-helmeted pilots in their cockpits.

As quick as the adrenalin has hit the pit of my stomach and the hairs risen on the back of my neck, they are gone. Only the sound of the air folding itself back into place remains. I am left breathless, though I haven’t moved a muscle, and I feel an overwhelming conviction, perhaps for the first time in my life, that one day I must do that myself. I resolve there and then that whatever else I try to do with my life, the first thing to attempt is to fly.

It is the summer of 2000. I am fifty-six years old and I am sitting on the banks of another river, fishing. I am content, the fullness of nature surrounds me, the fish are biting and the air is warm. I am thinking about nothing in particular.

A four-ship formation in transit. (Sqn Ldr S. Foote, OC 16(R) Sqn)

Suddenly, there is a noise off to my right; it is an ascending, rushing noise. I look in that direction. Round the bend of the river, at what seems only tree-top height, banking sharply, is a Jaguar: the RAF’s premier single-seat day-fighter. No sooner have I taken this in than a second one appears, in a loose trail position, echoing exactly the movements of the first as they rapidly reverse the bank angle to follow the course of the river.

I watch and the same rush of adrenalin occurs, the hairs on the back of my neck tingle and, as the Jaguars disappear and the air folds back into place. I muse that I am so thankful that I did, after all, get to do that myself, in several different aircraft types including the Hunter and the Jaguar. I realise that I miss it now and, with a regret that has no name, I’ll never do it again.

A pair of 16 Squadron B(I)8s take off for a bombing and gunnery sortie. (Gp Capt Tom Eeles RAF (Ret.))

B(I)8 XM 272 just airborne; the QRA shed is in the background. (Sqn Ldr S. Foote, OC 16(R) Sqn)

1

Baptism of Air

‘Daddy, when I grow up I want to be a pilot.’ Some might say that you can’t do both, but I said these words immediately after being set down from my first flight in an aeroplane. I was six years old and I’d just spent 10 minutes sitting on a large cushion in the front seat of an Auster, probably ex-Second World War, with a handlebar-moustachioed pilot who was definitely ex-Second World War (well, at least his moustache was). We had just flown from Southport Sands on a 10-minute ‘Round the Marina and Back in Time for Tea’ trip. I’ve no idea how much it cost my parents from their modest income, but it was worth every penny!

From then on I had an abiding interest in anything that flew: birds, butterflies, moths, but most of all aeroplanes. That interest was nurtured and encouraged by my father, who had always wanted to fly, but had been prohibited from doing so by his overbearing mother. When he finally, and clandestinely, went along to volunteer as aircrew in 1939 it turned out that two other things mitigated against his desire: an eyesight defect and the fact that, as an engineering draughtsman, he was in what was known as a ‘reserved occupation’. He spent his war as a member of the Home Guard, literally, for me anyway, Dad’s Army.

Throughout my childhood we visited every air show in reach. There was an annual one at nearby RAF Yeadon (now Leeds-Bradford International Airport) and I well remember walking back after the show, on a fine summer’s evening, lost in thoughts of being able to learn to fly.

As soon as I was old enough, I joined the Air Scouts and then the local Air Training Corps squadron. Along with fishing and rock-climbing, the ATC soon became one of the most important things in my life. The whole environment was immersed in a sense of being up close and familiar with military aviation and, for me, was a dream come true. We learned Morse code, went shooting, practised foot drill, we had our very own functioning Link Trainer, but most excitingly we actually went flying, at least once a year!

The ‘Link’ was the world’s first effective flight simulator. It had electrically and vacuum-operated instruments and moving parts. It could mimic the pitch, roll and yaw of an aircraft in flight, as well as simulate the progress of a flight from one place to another. The cockpit was a generic one, with most of the current instruments, knobs and levers. What’s more, it was all connected electrically to a wheeled device, known as the Crab, which drew an ink trail on a map resting on a nearby glass-topped table. It was a real boys’ toy!

As I advanced through the rank structure to sergeant, I was given increasing responsibilities for operating and supervising other cadets in the Link Trainer. Of course this meant that I had to become more proficient than them, so I did tend to ‘hog’ it! Whatever my level of expertise, which I don’t recall as being particularly good, it did increase my desire to do that sort of thing for a living. As did our annual summer camps at RAF stations, which always included at least one air experience flight. In my time with the ATC I flew in a Scottish Aviation Single Pioneer, several times in a Chipmunk, a Beverley, a Hastings and, most excitingly, in a de Havilland Vampire trainer. Little did I realise that a couple of years later I would learn to fly it.

As I approached my sixteenth birthday, I discovered that I could apply for a sixth-form scholarship with the RAF. This would, if I were successful, give my parents an additional small income while I stayed on at grammar school taking my A-levels. I would also have a reserved place at the RAF College at Cranwell, subject to achieving acceptable results in the exams. I filled out the plethora of forms and waited impatiently.

After what seemed an interminable time to an impatient teenager, I was sent a rail warrant to travel from Leeds to London and on to the RAF Aircrew Selection Centre at Hornchurch in Essex, where the initial round of interviews and tests were to be inflicted. This in itself was an adventure. Up to then I had rarely been out of t’North, let alone Yorkshire. Our next-door neighbour, Arthur Spoor, was a travel agent and so, in the view of my parents, a well-travelled man of the world. Accordingly, I was sent round to get a briefing on how not to get lost on the London Underground.

Suitably briefed I left my parents standing on the platform as the train left Leeds City station for London King’s Cross. I don’t recall being at all worried by the prospect of travelling all that way on my own and looked on it as a great adventure. Having arrived at King’s Cross, I tracked down the Underground station and successfully found the right line, the green one, and an hour or so later, alighted at the correct station. A street map of Hornchurch had been despatched with the rail warrant, so I successfully navigated my way from the station to the main gate of RAF Hornchurch. This was an edifying result, as my stated first choice of aircrew category was navigator. This, in turn, stemmed from my love of geography and maps!

As I made my way to the Candidates’ Barrack Block, I realised that I was treading the same ground as some of those Battle of Britain fighter pilots I had spent most of my formative years reading about. The two days of medical tests, interviews, aptitude tests and just sitting around waiting for the next event went by in a blur. The intervening evening was a real eye-opener as I fell in with some more experienced southerners and was taken on a tour of Soho, where we sampled some of the female anatomical education that was on offer.

On the second day there was a filtering out of the candidates, for all sorts of reasons; the main one seemed to be colour blindness. By late afternoon less than half the original number of us were left in the running. We were then told that we would be going by coach to the RAF College at Cranwell, in Lincolnshire, to complete the rest of the scholarship selection procedures. The next morning, duly fed with a good RAF full-fry, we boarded our springless RAF coach for the 150-mile journey north. I don’t know how long it took, but it felt like several lifetimes.

Eventually, we arrived at Cranwell and were accommodated in an aged building that was probably built personally by Lord Trenchard when he started the college in 1920; it had the grand name of Daedalus House1; I was hoping that I wouldn’t emulate Icarus!

Then followed a series of team and individual verbal and physical exercises, all designed to test our organisational and leadership skills, as well as seeing how we expressed ourselves. The only part I really remember is the question, ‘Who would you most like to bring back from history to see the world today?’; my answer was, ‘The Wright Brothers.’ There were yet more discussion and Q&A sessions, as well as more interviews. When would it all end? Well, after two days, we were sent on our way, with not the slightest hint as to where we stood.

After a couple of weeks back in the real world of school, ATC, coffee bars and Friday nights at the Mecca2 or the cinema (‘t’pictures’ in West Yorkshire parlance!), a brown manila envelope turned up in the post. It turned out to be a case of ‘good news and bad news’. The bad news first: I had not won a RAF sixth-form scholarship, so no money for Mater and Pater. The good news? I had passed all the tests and medicals sufficiently well to be offered a place in training as a navigator in Her Majesty’s Royal Air Force. The letter went on to offer me one of two choices. Either a reserved place at the RAF College, subject to me gaining two A-level passes, one of which had to be a science subject, or a direct entry place in training, once I had reached the minimum age of seventeen and a half years of age.

It didn’t take me long to decide; the direct entry meant that I could leave school and start flying in just over six months time! I told my parents that was what I wanted to do and they were very supportive; it became obvious that they had resolved not to repeat my paternal grandmother’s obstruction to my Dad’s dream. I returned the appropriate form to the RAF. The next half-year was going to be very long.

To help the time go by more quickly, I threw myself even further into ATC activities and was selected for an advanced gliding course, which I completed successfully in the summer of 1961. I had become the proud owner of a 250cc BSA C15 motorcycle and had passed my test at the first attempt. I had also picked up, on the back of the BSA, a new girlfriend! Life and the future looked immensely rosy – roll on the New Year!

Notes

1 I believe that it still graces the environs of Cranwell and houses the Headquarters of the Air Cadet Organisation, which in terms of personnel numbers is now larger than the RAF! The continued use of this old building enhances the view that I once overheard a US Air Force Colonel express when he saw the one-eyed navigator and peg-leg pilot dismount from their Canberra: ‘You Limeys! You never throw anything away!’

2 The name of a chain of dance halls.

2

Apprenticeship

The Officer Training course for which I had been selected started on 16 January 1962; I was seventeen years and eight months old. At that time the world was turning, not just into a new year, but more and more into a planet split between two superpowers – the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The bombs had been getting bigger for some years now; the atom bomb was old hat – the hydrogen bomb was the new terror over the horizon. The Cold War was hotting up.

After the disaster for the USA of the shooting down of Gary Power’s U2 reconnaissance mission over Russia, and Premier Kruschev’s belligerent response, there was a new, younger man in the White House. Here was a man who seemed to be willing to take on the USSR more directly. His name was John Fitzgerald Kennedy; like his native country, he would be henceforth known by his initials.

In the skies above us a new race was on – the Space Race. At the time I joined the RAF, Russia had a definite lead down the back straight, but things were moving in the west. The Soviets had successfully launched and recovered a dog from space and the Americans were trying hard to catch up, using a chimpanzee called Ham. Both sides had men waiting in the wings. With the cancellation of the Blue Steel project, the Brits had backed out of the race. To rub salt in that particular wound, the Italians launched their first rocket into space on 12 January 1962. Three days later I, and about fifty other likely lads, arrived at No.1 Initial Training School, RAF South Cerney, Gloucestershire, to start our Officer Training.

South Cerney was a grass airfield with a tarmac perimeter track and had last been active as a relief landing ground for the Central Flying School at RAF Little Rissington, about 15 miles away. In 1962, however, the only aircraft that came near the place were USAF B-47 bombers flying into nearby Fairford. The sole activity on the airfield now was the regular strings of hot, panting bodies running round the perimeter-track with varying loads on their backs.

There were four months to be endured – four months of foot drill, rifle drill, sword drill, mathematics, public speaking, RAF Law, physical exercise of all kinds and even lessons in Officers’ Mess etiquette. Aerodynamics and meteorology were about the only things we were taught that seemed to have anything to do with aviation. However, the main result was the forging of friendships in adversity.

We started by inhabiting cold, stark barrack blocks, with about twelve to a room, then, after a month, we moved to what was called No.2 Officers’ Mess, with its wooden huts and individual hutches, but a ‘proper’ officers’ dining room. At around this time, during one classroom session a staff officer had come in to ask whether any of the Cadet Navigators would like to become Cadet Pilots. He explained that there was a shortfall in the number of trainee pilots on our course. He then sugared the pill by explaining that anyone who didn’t make it through training as a pilot would be automatically re-streamed to navigator training.

The staff officer said that he didn’t want answers right away, but should any of us wish to take up the offer then we should report to his office by the end of the day. During the mid-morning break, I pondered this possibility. Since going through selection, almost a year ago, I had completed an advanced gliding course and was feeling much more confident about my ability to pilot an aeroplane. I had also learned that I had passed all the aptitude tests required for selection as a pilot. My gliding instructors had been surprised when I told them I was aiming to be a navigator. By the end of that day I had duly reported back with a positive answer and so, by that evening, I was a Cadet Pilot.

As a lad of fairly short stature, curly blond hair and a tendency to chubbiness, I was, and hopefully still am, one of those lucky souls who look young for their age. However, when I was going on eighteen it was occasionally a drawback. For instance, one day we had to report for some sort of physical fitness session and I had acquired a new, red tracksuit; most of the other guys were in the RAF issue kit. When we were lined up the Sergeant Physical Training Instructor stood in front of me and, due to his massive build, towered over me.

‘What are you doin’ ’ere?’ he growled.

‘I’ve come for the PT, Sergeant,’ I replied nervously.

‘Well, kids from the married quarters don’t join in with the courses. Go home!’ he ordered.

‘But I’m not from the married quarters, Sergeant, I’m on the course.’

He looked surprised, muttered something about his sadness at getting older and walked away. This happy problem would bug me many times in the future. For instance, for some years to come I frequently had to show my RAF Identity Card to pub landlords!

After three months at South Cerney, we were sent on a six-day field exercise in the Brecon Beacons, where it was hoped that boys would be turned into men. A reasonable hope I suppose, but it was more like a grown-up Scout camp; lots of hard exercise up and down mountains; semi-arctic weather for some of the time; and lots of messing about with ropes, pulleys and bits of wood. The best bit was getting a turn in the cookhouse with what appeared to be a disaster waiting to happen in the shape of a pot-bellied, gas-fired heater called a Hydraburner.

The thing that I remember best about those few days was when one of our erstwhile staff, Flight Lieutenant Dave Goodwin, beat the hell out of the campsite in a single-seat Hawker Hunter on the penultimate day. Cheered mightily by that, and after a long, sore-footed march to Abergavenny, we piled on to another suspensionless RAF coach and, despite the discomfort, slept all the way back to Gloucestershire.

Our reward was to be graduation to No.1 Officers’ Mess for our final month. This was it. We now felt like proper Officer Cadets. We were, at last, inhabiting rooms in a building that had been built expressly for the purpose of housing officers. After the weeding out of more of our comrades, who were persuaded to seek employment elsewhere, we had come to the final hurdle. En route to this point we had gelled into a fairly cohesive band of brothers, special friendships had been forged in the fires of duress and we were all eager to escape into the world of the ‘real’ Royal Air Force, wherever that might take us.

Our passing out parade was held in early May on the parade square, which was surrounded by flowering cherry trees. The day was fine, warm and there was a light south-westerly breeze nudging small, fluffy cumulus clouds across the sky. The reviewing officer was Air Marshal ‘Bing’ Cross; the then boss of Bomber Command. During the rehearsals I had slipped and fallen while carrying my rifle. This carelessness had broken a finger on my left hand so I was now unable to carry rifle or sword. I was thus accorded the privilege of being a ‘spare part’ at the back of our flight.

After much rehearsing under our, by now, much beloved senior drill instructor, Flight Sergeant Jim Maunder, we had reached a level of skill and presentation which he deemed just acceptable. We thought we were fit for parading outside Buckingham Palace! We marched on to the parade ground, watched by the staff and many families and friends, and then waited. Eventually the hour arrived and, as the Air Marshal took his place on the dais, our parade commander brought the parade to the ‘Present Arms’, the band struck up and a huge, white Victor bomber appeared from behind the barrack blocks and swept majestically over the parade ground. It was almost impossible not to turn and follow it with my eyes; in fact, being at the back and of short stature, I did sneak a longer look than I should have and very nearly lost my hat in the process. Nobody seemed to notice.

After much marching back and forth, many fine but forgettable words and the prize-giving, we finally left to the strains of the RAF March Past, all wearing our ever-so-thin Acting Pilot Officers’ rank tapes with great pride. Now, finally, was the time to retire to the mess and partake of tea with visitors and staff, make phone calls or send telegrams to parents who, like mine, were too far away to be there and then just let go for the evening. What was next we wondered?

3

Learning the Basics

For me it was back to my native Yorkshire, to RAF Leeming in the Vale of York. During my time at South Cerney I had teamed up with a few like-minded individuals and had made some new, close friends. I was now learning that a feature of RAF life would be that those new, close friends will be posted elsewhere and that you will have to go through it all again at the next place.

An impish young man called Colin Woods and I had struck up an alliance against authority very early on. Together we had paid the princely sum of £50 to buy a 1934 Lagonda saloon car from one of the staff at South Cerney. This thing was a monster with a bonnet that seemed about 9ft long, under which was a 3½-litre straight-six ‘marine’ engine. I didn’t have a car driver’s licence so, fortunately, I didn’t drive it on the public road. However, I knew how to drive a car because I had driven the Air Training Corps Gliding School Land Rovers all over RAF Linton-on-Ouse and Colin had given me more lessons on the narrow twisting roads of RAF South Cerney. The greatest difficulty with the Lagonda was that the pedals didn’t come in the right order and it was extremely easy to accelerate when you should be braking, and vice-versa! When we had left South Cerney, Colin had bravely taken the Lagonda the 250 miles north, to his home in West Hartlepool, where he thought he might have a buyer. We even hoped for a bit of a profit. Sadly, it was not to be, the machine broke down and when Colin finally got it back, extensive woodworm was found in the coachwork and she had to be laid to rest. I think I got a tenner back!

In mid-May 1962, Colin, some others from South Cerney and I turned up at No.3 Flying Training School, RAF Leeming, to learn to fly. We had, as usual, received lots of paperwork to be completed during the short leave period between courses. The reporting details stated that we should arrive before 4 p.m. and go to the Ground School for an address by the senior staff. There would then be a written exam and in the evening we would retire to the Officers’ Mess Bar, where we would meet our flying instructors.

After we had taken our seats a stream of senior officers gave us the repeated message that we were there to work and not play. The Station Commander seemed very young to me; I concluded that he must be one of the ‘high fliers’ I’d heard about. Perhaps there was hope for rapid career progression in this business? Then the exam papers were handed out. We were given half an hour to complete the twenty or so questions.

Some of them were a bit strange, like: ‘Who is responsible for controlling the height of trees on the airfield?’ Multiple-choice options:

A The Senior Air Traffic Control Officer (SATCO)

B The Station Commander

C God

I’d no real idea but I gave it my best effort.

After that we returned to the Officers’ Mess, where we were told to change into PE kit and were given a series of demanding physical exercises, including some rather strange jumps and hops, at the back of the mess, in full view of those eating dinner. After showering and eating we were told that we were to report to the bar, where we would meet our flying instructors – and that they would expect us to buy the drinks. It seemed that we had hit the ground running! Nevertheless, a pleasant, if expensive, evening was passed in the company of our would-be instructors, much beer was consumed and respectful banter exchanged. And so to bed.

The next morning, after breakfast, we were told to make our way back to the Ground School again. There we were addressed by a series of officers all claiming to be the men who had addressed us the previous afternoon. Rats began to be smelled. At least these chaps appeared to be the right ages for their ranks. Then we started the serious work of receiving books, publications, filling in endless arrival proformae – just how many times do you have to write your full name, rank and service number for the station to keep track of you?

When we returned to the mess for lunch, the first person I bumped into was my flying instructor. I greeted him and asked him if he had slept well; it seemed sensible to be polite. Then I noticed that he was chatting to the Chief Flying Instructor and the Station Commander – neither of whom was wearing the correct badges of rank. When the question mark so obviously appeared above my head they could no longer keep their faces straight, in fact they became extremely bent.

They were all from the senior course in residence and they had obviously arranged the previous afternoon’s and evening’s events; no doubt with the collusion of the aforesaid senior officers, who had probably thought that it was a ‘wizard wheeze’! Apparently the whole introductory ‘exam’ was dreamt up in collusion with the staff. The answers to most of the questions was actually ‘none of the above’! They had got away with it because most of them were graduates and ex-University Air Squadron members, so their average age was well above ours. We were just about all school leavers and not many of us were over twenty. The joke was on us, but in the evening they said they would help us entertain our real flying instructors.

Then there was lots of ‘admin’ to do; the most exciting part of which was to be issued with our flying kit, including two light blue flying suits, the silver ‘bone-dome’ and its inner helmet and oxygen mask. The least exciting part was to be issued with a whole armful of documents and APs (Air Publications), including our Pilots’ Notes and the AP 1234. The latter was a weighty tome, in two parts, that told one all one needed to know, and lots of things one didn’t need to know, about aviation and all its related sciences. Along with all these books there were the plethora of ALs (Amendment Lists), which had to be incorporated in the said volumes. I sat on the floor of my bedroom that evening, surrounded by pages extracted and pages to be incorporated, trying desperately not to mix them up. Then after all those had been done there were the ‘Handwritten Amendments’. My spirits finally rose when I came across the following instruction: ‘AP1234, Part 4, Chap 6, Page 3, Line 7: For “heliocoptre” insert “hicopleter”.’ Even to this day you can tell someone who joined the RAF as a pilot in the early 1960s through the fact that they will refer to those whirling dervishes of aviation as hicopleters!

By now, we Acting Pilot Officers had met up with the other half of our course, the Sergeant Pilots. These were all ex-airmen who had been selected as potential NCO pilots.1 They increased the average age of the course to something more fitting and, as we were to discover, brought us some very useful corporate experience of service life.

After a few weeks in the classroom we were finally allowed near the aircraft, which was the Hunting Percival Jet Provost Mark 3 – known universally as the JP 3, or more often as the ‘constant thrust, variable noise machine’. This sobriquet was an allusion to the miniscule thrust of the Rolls-Royce Viper engine; a power unit originally designed for a short life in the Jindivik radio-controlled pilotless target drone. In Ground School we had spent many hours in what was called the Procedures Trainer, a real JP 3 cockpit section furnished with all the correct dials, knobs and switches. This training aid was there to help us learn all the checklist items required throughout a flight, from before starting the engine to shutting it down again and getting out and leaving the aircraft in a safe and tidy condition. We were constantly reminded that we should know all the checks and emergency procedures by heart before we would be allowed to fly on our own. In fact, if we didn’t it would not go down well with our flying instructors, known as QFIs2 and who were to be invariably addressed as ‘sir’.

So it was that the day finally dawned when I was to make my first flight with my instructor, Flight Lieutenant Wally Norton. It was a nerve-wracking, exciting, scary and exhilarating experience. The actual handling of the aircraft was not too much of a mystery to me. With the exception of the fact that we were not constantly descending, it wasn’t so different to flying a glider. There was, of course, the additional throttle lever, which fell easily into my left hand, to control the output of the Viper jet engine only a few feet behind me, and the fact that we were zooming round the sky at about 200mph!

With Wally’s gentlemanly and patient help I gradually picked up the various motor skills, got better at remembering my checks and learned to speak correctly on the radio. After a couple of weeks, during my twelfth flight, he suddenly announced that I was to land and take him back to the dispersal area where he would get out and I was to go and fly a circuit all on my own. On the way he asked me what my callsign was, I told him ‘Romeo 56, sir,’ and he said, ‘Practise it and don’t go using mine!’

We were marshalled back onto our spot on the dispersal line and Wally dismounted. A rather crude wooden triangular device was then put on his seat and the groundcrew fastened all the straps round it. This contraption was called a ‘dummy’ so I hoped that there was still only one dummy in the cockpit. I then restarted the engine and called ATC for permission to taxi. But I was wrong, there were two dummies in the cockpit!

Out of the habit of the last twelve flights I used my instructor’s callsign! The controller must have been used to this and Wally was up there beside him. He replied with my own callsign and let me loose on the aviation world.

Everyone had said that your first solo would be something you would never forget and it’s true. The excitement, tempered with an overwhelming desire not to screw up, led to a tightening in the throat and butterflies in the stomach. These feelings soon gave way to elation as I lifted-off and committed the act of solo aviation in a powered aircraft for the first time in my life. The elation was rapidly replaced by concentration on getting everything right. After all, this first solo flight was only going to last a few minutes, just the time it would take to make a single circuit of the airfield and land. I concentrated on achieving the right height and speed, making my turns level and accurate, and flying exactly parallel to the runway.