Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

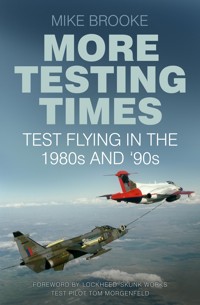

Following his first three successful books, describing his long career as a military pilot, Mike Brooke completes the story with more tales of test flying during the 1980s and '90s. During this period his career changed to see him take control of flying at Farnborough and then at Boscombe Down, as well as off-the-cuff delivery missions to Saudi Arabia, 'bombing' in the name of science in the Arctic and the chance to fulfil a long-standing dream and fly the vintage SE.5a. This often hilarious memoir gives a revealing insight into military and civilian test flying of a wide range of aircraft, weapons and systems. As in his previous books, Brooke continues to use his personal experiences to give the reader a unique view of flight trials of the times, successes and failures. More Testing Times and its earlier volumes make for fascinating reading for any aviation enthusiast.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 514

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MORE TESTING TIMES

BY MIKE BROOKE

A Bucket of Sunshine: Life on a Cold War Canberra Squadron

Follow Me Through: The Ups and Downs of a RAF Flying Instructor

Trials and Errors: Experimental UK Test Flying in the 1970s

More Testing Times: Test Flying in the 1980s and ’90s

MORE TESTING TIMES

TEST FLYING IN THE 1980s AND ’90s

MIKE BROOKE

For Linda

First published in 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved

© Mike Brooke, 2017

The right of Mike Brooke to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8188 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

A Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Prologue

Part 1: Preparation

1 1984

2 The Briefing Team

3 Airborne Again

Part 2: Farnborough

4 Taking Up the Reins

5 Defining the Job

6 Flying the Ferries

7 ‘Sea King’ Further Employment

8 Fast Nightbirds

9 A Slow Nightbird

10 Bombing the Arctic Ice

11 To Arabia

12 Other Overseas Jaunts

13 The Air Shows

14 Flying Back in Time: The SE.5a

15 A Retrospective

Part 3: Boscombe Down

16 Back to the Future

17 The Yanks are Coming!

18 Helping Out

19 My Very Own Trial

20 Pushing the Envelope

21 Operation Granby

22 SETP and a Blackbird

23 Moving On

Part 4: Civvie Street

24 Club-class Gypsies

25 Cranfield University

26 Slingsby Aviation

27 International Test Pilots’ School

28 Texas

29 Back to Square One

Epilogue

Appendix 1 Aircraft I Have Flown

Appendix 2 Glossary

A DEDICATION

To Air Commodore David L. Bywater FRAeS FIMgt RAF (Ret.)

In planning this series of books I had hoped to ask the test pilot for whom I had worked during three tours of duty, Air Cdre David Bywater, to pen the foreword to this volume. Very sadly, especially for his family and everyone that knew him, David passed away on 24 September 2015, aged 78. I was honoured to be asked by his wife Shelagh to help officiate at his funeral and memorial service.

David Llewellyn Bywater was born on 16 July 1937 and was educated at the Liverpool Institute High School for Boys, where he was a keen rugby player and an excellent swimmer. He joined the Combined Cadet Force, won a flying scholarship and qualified for a private pilot’s licence in the Miles Magister. He was awarded a scholarship to the RAF College Cranwell in April 1955 and graduated in 1958.

David was posted to RAF Gaydon to fly the Handley Page Victor Mark 1 with XV Squadron, which then moved to RAF Cottesmore. This was a busy time for these early V-Force squadrons, as the nuclear deterrent role was developing at a rapid rate to keep up with the growing Soviet threat. David showed his piloting and technical skills from the start and helped develop the scramble start procedures that were demonstrated at the Farnborough Air Show in 1959 and 1960. Meanwhile, he completed the Intermediate Captain’s Course to qualify to fly in the left-hand seat.

Air Cdre David Bywater in test pilot mode. (Courtesy of Shelagh Bywater)

In the spring of 1961, he returned to RAF Gaydon as a Victor captain and, over the next two and a half years, he and his crew flew more than 700 hours, gained the top Bomber Command rating of ‘Select Star’ and achieved a very creditable second place in a bombing and navigation competition against crews from all the RAF’s V-Force squadrons.

In 1963 David was selected to attend the 1964 Empire Test Pilots’ School (ETPS) course at Farnborough. From the course he was posted to B Squadron at A&AEE Boscombe Down, where he became re-acquainted with the Victor. He also flew the Vulcan for the first time and was able to compare the two V-bombers while flying release-to-service trials for the Terrain Following Radar.

After attending the RAF Staff College at Andover in 1969, David was posted to HQ RAF Germany as an Operational Plans Staff Officer. One of his major tasks was to plan the introduction of the Jaguar as a strike aircraft and the construction of hardened aircraft shelters on RAF bases in West Germany. In 1974 he returned to the UK to take up the post of Officer Commanding (OC) Flying at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, where – apart from managing all aspects of experimental flying – he was heavily involved with planning and managing the flying display for the Farnborough Air Show. After a staff tour at the Ministry of Defence (MOD), in 1981 David was promoted to group captain and returned to Boscombe Down as Superintendent of Flying. This was a busy time, particularly during the build-up to operations for the Falklands War, when emergency clearances were required for some unusual combinations of systems, weapons and aircraft. In 1985 David moved on to the RAF Staff College, Bracknell, as a group director, where he helped many young officers expand their knowledge and improve their career prospects. It was no surprise that his final RAF appointment would be to return to Boscombe Down as the Commandant, on promotion to air commodore. He retired from the RAF in 1992 after what can only be described as an extremely successful RAF career.

David’s second, civilian, career began when he joined Marshall Aerospace of Cambridge as Airport and Flight Operations Director. Over the next ten years, he was responsible for major improvements to the airport, including the construction of a new ATC tower, installation of a radar instrument landing system and a modernised airfield lighting system. He also maintained his commercial pilot’s licence together with a flying instructor’s qualification and continued to fly company aircraft. He amassed a further 1,000 hours’ flying time on a variety of civil and military aircraft types, bringing his total hours to more than 4,000 on 155 aircraft types; only such an enthusiastic test pilot could have achieved that.

David was a Fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society, Fellow of the Institute of Management, Liveryman of the Guild of Air Pilots and Navigators, Vice President of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association and of the Royal International Air Tattoo, Honorary Member of both the Airport Operators Association and the Cambridge University Air Squadron, a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots and of The Air League, past Chairman of the XV Squadron Association, committee member of the No. 104 Cambridge Squadron of the Air Training Corps and Director of the RAF Charitable Trust. That very impressive list summarises David’s major contribution and dedication to so many aspects of British aviation.

David Bywater was meticulous in all he did, whether it was planning and flying a sortie, managing major updates of operational facilities or checking on tides and currents when sailing, which was another of his passions. He was highly respected and admired by all who worked with him or were involved with him socially. He is survived by his wife Shelagh, whom he married in June 1960.

I first met the then Wg Cdr David Bywater, very briefly, while on a visit to Boscombe Down shortly before I joined the course at the Empire Test Pilots’ School (ETPS) in 1975. When I graduated at the end of that year I went to the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough where he was OC Flying. During that tour I discovered what a first-class senior officer he was; he always had time for us junior guys and was ever ready to socialise with us, as was his wife, Shelagh.

Two years after the end of my tour at Farnborough I was posted to ETPS at Boscombe Down and the now group captain, David Bywater, was the Superintendent of Flying. We had both gone up a rank, but he was still a man who would listen and consider before deciding on action: qualities of a true test pilot. During that tour both David and Shelagh went out of their way to help, encourage and support my children and I when my marriage failed.

David finished his RAF career in a truly fitting appointment for a test pilot of his experience and quality as the Commandant at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down – by then familiar territory for both of us. Yet again, and deservedly so, he had stayed two ranks above me and once more his measured wisdom and unflappable character made him an excellent leader and manager. Most of all, the solidity of his marriage and family life gave him a stable base. He was and still is an inspiration to me. I am very grateful to Shelagh, and David’s family, for agreeing to me making this dedication; and to his brother-in-law, Air Cdre Norman Bonnar for helping me with its compilation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I cannot overemphasise the part played by my wife and soul mate Linda in getting this book to a state fit to publish. She has, now for the fourth time, been wonderfully supportive in reading, correcting, suggesting and criticising my writing. I cannot thank her enough.

Thanks are also due to many other erstwhile colleagues and helpers without whom this tome would not be so well illustrated or contain the right ‘facts’; in particular Roger ‘Dodge’ Bailey, Peter ‘Toggie’ James and Rogers Smith for refreshing my flagging memory banks. To ex-RAE colleagues Tony Karavis, Phil Catling and Graham Rood for helping with illustrations; the latter two are very involved with the Farnborough Air Sciences Trust (FAST), which can be found at www.airsciences.org.uk. My thanks also to Tim Prince, of Royal International Air Tattoo fame, for connecting me with professional photographer Peter March, who has very kindly provided many of the photographs. Lastly my gratitude extends to all the wonderful, anonymous souls who put lots of relevant info on the internet!

My very sincere thanks also go to my good buddy and fellow test pilot Tom Morgenfeld for writing the foreword to this book. I have known Tom since we shared the experience of the ETPS course in 1975, where I know he particularly enjoyed flying the Canberra T4; we have remained good friends ever since. Tom went on from ETPS to become a test pilot for the US Navy and the USAF, the latter on still-classified projects. After retiring from Naval Aviation he worked for many years for Lockheed at their famous ‘Skunk Works’. Tom flew the first flight of the second YF-22 prototype (pre-cursor to the F22 Raptor), many test flights in the F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighter, and he finished his career by flying the first flight of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, now known as the Lightning II. Tom is a past President of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots and finished his naval career as a captain in the US Naval Reserve. He once baulked at the media’s use of the description ‘legendary’, but that is typical of the modest guy he is – I think the word applies in full.

Last, but by no means least on my list of folk to thank, is the team at The History Press without whom I might have had to publish this myself! Especially my commissioning editor, Amy Rigg, and her colleagues Chrissy McMorris and Andrew Latimer.

FOREWORD

The email was short and straight to the point, just like the author himself. (Sorry Brookie, no pun intended … really!) It read, ‘I’m getting close to finishing the writing of my latest book – More Testing Times – that covers the time of my RAF career from 1984–94, which included two flight-testing tours, and then continues to the very end of my flying in 2004. I would very much like it if you could write the Foreword.’ Never being one to turn down a friend, especially one as close as Mike Brooke, I gave him a cheery, ‘Wilco!’

Immediately thereafter it began to dawn on me that I had absolutely no idea of how to approach this humbling and important task! So, for all you literary folks out there, please accept my apology if this fails to meet your expected standards. For those more intent on getting to the meat of this fine book, I say, ‘Good for you, this is all the Foreword you probably need.’ Get on with your reading! For those somewhere in between, I’m reminded of the great Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong’s reply when asked how he came up with his music: ‘I just blows what I feels.’ If you have the time, please give me a second to toot what I feel about Mike and this excellent book.

I first met the cherubic Mike Brooke in January 1975, the day after we moved to England for test pilot training at ETPS. Instantly we became friends and have remained so ever since. Mike’s effervescent personality, aviation savvy and piloting skills were appreciated as a rare gift by all, but it was his innate leadership that propelled him to become the de facto leader of our class. In addition to enduring the normal student struggles, Mike was the glue that held our diverse group together so closely, both professionally and socially. His spur-of-the-moment caricatures were loved by all. Indeed, his ‘Diary and Line Book’ recounting our course’s tumultuous year, complete with those caricatures, photos, quotes and even movement orders, is worthy of independent publication in itself. It clearly illustrates what a vital asset Mike was to the entire class.

As his career progressed, Mike continued to use his gifts in ever more important postings. His uncanny intimacy with aeroplanes, coupled with his uncompromising sense of integrity made him a most successful test pilot. His easy-going yet strong leadership style made him a most successful officer. That he was named a Fellow of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots alone puts him at the top of the heap.

Here I must give you an idea about his character. I have one big debt that I owe in part to Mike, of which he may not even be aware. Simply through his example as a committed Christian, he encouraged me to rekindle my faith. For that I will be eternally (literally!) grateful.

Mike’s fascinating aviation career has spanned everything from being a teenage Cold War warrior to being a world-class test pilot, and back to being an inspiration to young hopefuls on an Air Experience Flight. His résumé of aircraft flown reads like the index to Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft. Besides operational flying and testing, he’s done everything from instructing to performing flight demonstrations to humanitarian flying. So go ahead, brew yourself a cuppa and settle in to read about the career of one of the finest gents ever to don RAF flight gear. I know you’ll enjoy it.

Tom Morgenfeld May 2016

PROLOGUE

It’s really dark outside the cockpit. As black as the ace of spades. In fact it’s pretty dark in here too; just a soft greenish glow from the flight instruments illuminates my flying-suit legs and gloved hands. There are two of us, crammed cosily together, side by side, as our much-modified Hunter T7 skims along at 250ft above the undulating night-time English countryside at a speed of 420 knots (close to 500mph).

I can only see the ground ahead and around me because I have the latest generation of night-vision goggles attached to my helmet. I also have a large head-up display (HUD) right in front of me showing a moving image of the ground ahead in monochrome greens, overlaid by all the flight information that I need to fly the aircraft safely and efficiently.

I can manoeuvre over the hills and into the valleys, turn to change direction while maintaining the low altitude and get a clear sense of my speed and height as the scenery flashes by below us. It’s not as easy as doing it by day, but it’s not far off. The adrenalin helps keep the concentration level up and the navigation system keeps us on track towards our target.

It is April 1987 and it is ten years since I was doing this last, in the very same aircraft, Hunter T7 WV 383, of the same unit: the Experimental Flying Squadron at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough, Hampshire, in southern England. Ten years back we were just starting to experiment with what are known as electro-optical aids, to allow fast-jet military aircraft to fly covertly towards their targets, below radar, at night. Then we had a low-light television (LLTV) camera mounted in the Hunter’s nose and a small TV screen set into the right-hand pilot’s instrument panel. Comparatively speaking, it was all pretty crude; but it worked to a degree. We occasionally frightened ourselves but nobody died!

The problem with LLTV was that it needed some external light to enable it to present its images to the pilot. That minimum light level was defined as clear starlight – a night of overcast skies was no good. We had started, as in all test flying, cautiously and progressively, gradually lowering the heights and increasing the speeds, but when I left the RAE in 1978 there were still several problems to be solved before one could say that low-level high-speed night navigation and attack was feasible in all light levels.

In those intervening years, while I had been testing radar systems, teaching pilots the art and science of test flying and being guided into the realms of senior management and leadership, things had progressed. But now I was back at the sharp end of experimental flight-testing at Farnborough. However, I was no longer doing much of the flight-testing myself. My appointment as OC Flying meant that I was overseeing the flight-test programmes, as well as managing the increasingly scarce resources that allowed the Experimental Flying Squadron to achieve the results required by our rapidly modernising air force.

So how had I got here? By 1987 I had fully expected to be still doing ‘penance’ on a ground tour, behind a desk with little prospect of getting back into the esoteric and fascinating world of flight-testing. This book will take the story on from the point where I was first told, ‘Brookie, you’re grounded, but it will be good for your career.’ Words that were new to me on both counts!

PART 1

PREPARATION

1 1984

As 1984 took over from its temporal predecessor the world was still locked in the throes of the war that had become known as ‘Cold’. The two main protagonists of that war, the USA and the USSR, would carry out nuclear weapons tests throughout the year. Even France and China would join in with their own experimental explosions. Two right-wing politicians, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, were working in concert to confront any expansionist ambitions of the Russian Bear. Both the USA and the USSR had active space programmes – the Space Shuttle and Soyuz projects respectively – and the USA was embarking on a missile-based self-protection scheme that would become known as ‘Star Wars’. Another missile-based programme had matured sufficiently for them to be deployed to sites in Europe – the cruise missile. In 1984 the world was still an unsafe place and Europe was still the potential front line.

Twenty year earlier I had been despatched to that front line, where NATO forces were ranged against the forces of the Warsaw Pact. I was based in West Germany, flying the Canberra twin-jet bomber in the low-level strike/attack role; ‘interdiction’, we called it. We had nuclear weapons; we called them ‘Buckets of Sunshine’. During the two decades that had passed since those days, the fundamental East–West stand-off had not changed. Many summits and treaties had come and gone but, like my parents’ generation in 1939, we had no idea that the Cold War had only another five years to run.

The year 1984 had an ominous overtone for my age group thanks to the disturbing book written by George Orwell, published in 1949. His dark novel Nineteen Eighty-Four told a very sinister tale of a dystopian world after a nuclear war, set in a devastated land called ‘Airstrip One’, once known as Great Britain. Reading the book, as well as viewing the film and TV versions in the 1950s, had given people of my vintage an uneasiness about the arrival of that year, despite the fact that nuclear war had not yet happened and that democracy and not dictatorship still existed in our sceptred isle.

In January 1984 I had been serving in the RAF for twenty-two years, employed throughout that span as a pilot in a variety of roles and places. In all that time I had spent less than six months not flying – ‘grounded’ – while I recovered from a medical problem. But in late 1983 those in charge of stopping aircrew from having fun had found me out and earmarked me to be sent to the Advanced Staff Course at the RAF Staff College. That meant I was going to be prepared for senior leadership and management. Of course, at this point I had no idea what the future might bring.

My recent private life had become somewhat turbulent. My marriage of seventeen years had been dissolved and I had spent my last year on the staff of ETPS as a single parent. However, the silver lining was that during 1983 I had met, fallen in love with and proposed to a lovely lady called Linda. Our marriage was set for spring 1984. The only slightly darker cloud on my horizon in that year was that I would turn 40 years of age in April. This was a milestone that seemed have arrived far too quickly.

But 1984 would turn out to be much better than I could have imagined. As planned, I married Linda in March and we moved that very day into a brand-new, three-storey town house in central Oxford, which had sufficient room for our four children and us. As our relationship had blossomed during the previous year we had both felt drawn back to our childhood Christianity and we had started attending a local church regularly. We were, through the family of that church – St Ebbe’s, Oxford – reintroduced to Jesus Christ. Over the first year of our marriage our faith grew and matured and has been a central part of our lives ever since.

In 1984 the RAF Staff College was located in an enclosed green oasis in the brick-clad environs of suburban Bracknell, in the Royal County of Berkshire. There I would spend almost a year as a student again, living in the Officers’ Mess, and commuting to and from Oxford at the weekends. I was supposed to learn how to become a useful and knowledgeable member of the middle and senior leadership cadre of the RAF. There would be no flying and the only airborne activity I would see would be the airliners going in and out of London Heathrow airport, only a handful of miles to the east.

The Advanced Staff Course turned out not to be as dire as I had at first imagined. There were about ninety of us students from a couple of dozen nations. We were split first into three groups and then into syndicates of seven or eight. There were going to be three terms and we would therefore have three tutors, known at Bracknell as DS (Directing Staff). My first DS was Wg Cdr Ian Dick. Ian was a past leader of the RAF Aerobatic Team, the Red Arrows, and I had briefly flown with him as his instructor when he arrived at the Central Flying School to fly the Chipmunk, ahead of him taking command of a university air squadron. This route had been curtailed when he was diverted to take charge of the ‘Arrows’.1

The staff course had a multitude of paper exercises, a great deal of writing, plenty of listening to distinguished speakers, lots of socialising and two periods when we mixed with the students and staff from the army and navy staff colleges for joint exercises.

There was also a European tour, which included a visit to Berlin. There we were able, in uniform, to visit East Berlin. Although it is difficult to imagine now, more than thirty years later, as a one-time ‘Cold War Warrior’ I had a palpable frisson of excitement, mixed with trepidation, as we passed through the Berlin Wall at Checkpoint Charlie on our way to a Soviet military museum inside East Berlin. The contrast with the western half of the city was immediately obvious. The roads were rougher and, apart from the smoky little cars called Trabants, traffic was lighter. The citizens’ tenement living quarters were tall, grey and awfully drab. There was also a very noticeable lack of advertising hoardings, adding to the bleakness.

When we reached the museum we came face to face with Warsaw Pact soldiery. The enlisted men’s uniform looked as dowdy as the rest of the place; the material was rough and they were what any decent guards regiment sergeant major would call ‘a right shower’! I was so taken with looking at these chaps, many of whom were but spotty youths, that I missed seeing a sign that said ‘Niet Fotografy’. Hence about halfway through our visit I was hailed by one of the aforementioned khaki-clad young men who told me, in Russian, that I was breaking the rules. I didn’t hear the mention of Lubyanka or the Gulag, but he did rip my camera from my grasp, open the back and pull the film out. Of course at this stage I had no idea why and began to get a bit indignant. This was not a good move. More spotty soldiers arrived, but one of my compatriots said that there had been a sign at the entrance banning photography, so I backed both off and down. I even tried a smile and lots of ‘Sorry – sorry – didn’t see the sign’. This seemed to placate the reds and I was left to put my camera back together. I know I brought it on myself but I had lots of other quite legitimate snaps on that film!

We also visited the Berlin Air Safety Control Centre. There, military officers from all four occupying powers – the UK, USA, France and the USSR – worked together to regulate all air traffic coming into Berlin. Aircraft coming to Berlin from the west used three established air corridors so that they could overfly East Germany safely. It was another glimpse into the effects of the Cold War. Something that I, twenty years earlier, sitting at a couple of minutes’ readiness with a live nuclear weapon, had no concept of. The Russian officer we met seemed rather jolly, although I suspect that he could not be easily backed into a corner.

When we got back into our coaches and set off to return to democracy I noticed a road sign that indicated this was the route to Prague and the distance was about 350km. That really brought home to me that we truly were inside the Warsaw Pact bloc. The thought that East Berliners could drive to Prague in about three hours was, in 1984, amazing to me; that is if they had a car or were even allowed to!

If I’d thought that the contrast between East and West was vivid on arrival in the East, it was even more apparent as we travelled back into the West. It was as if someone had been decorating the place while we were away. The liveliness and colour, openness and commercialisation shouted the good life to one and all. That must have really upset the East German President, Erich Honecker, and his cronies. One thing we learnt that really did distress the East German apparatchiks was the effect of the sun shining on the Fernsehturm TV tower. The tallest structure in Germany, the tower was built in the late 1960s by the communist German Democratic Republic under the then President, Walter Ulbricht. It was meant to be a symbol of the GDR’s strength. Two-thirds of the way up the 365m needle there is a globe of glass and steel – a restaurant and observation deck. The top half of the globe, which was modelled on the first man-made satellite, the Soviet Sputnik, is made of stainless steel tiles. Whenever the sun shines on this burnished orb a large, bright cross can be seen from all over the city. Berliners nicknamed the luminous cross the ‘Rache des Papstes’, in English the ‘Pope’s Revenge’.

In 1984 we were still less than forty years from the end of the Second World War, whose outcome had led to this island of democracy in a sea of communism. There were some hesitant signs of the Cold War thawing, through the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), but the rhetoric flying back and forth across the Iron Curtain was still pretty vehement at times.

There were other visits but none made the impression on me that this one did. In other locations, we learned at first hand about much of the command-and-control systems within NATO, even visiting its headquarters in Belgium. Of course, all these visits had a social side that served to educate us even more: from mussels and chips with Belgian beer in Brussels to breakfasting and dining with the Royal Navy in the Painted Hall at Greenwich, designed by Christopher Wren. As we looked in awe at the ceiling inside this magnificent edifice, which rivalled that of the Sistine Chapel, one of our dark blue compatriots said, ‘If the answer is 133, what is the question?’ Nobody came up with a decent guess. Later we learnt that it was the number of breasts on view (one of the nubiles had only one uncovered!).

Another great day out – for what educational purpose I am not sure – was to Epsom for the Derby. We had our own tent in the centre of the racecourse with refreshments arranged by the Officers’ Mess at Bracknell; Linda dressed for the occasion and looked stunning – more Ascot than Epsom! Indeed, while we were walking around the fairground that is a feature of Derby Day, a lady at one stall said to her, ‘’Ere my love, you do look good, but yer at the wrong racecourse, ain’tcha?’ Not only did we win a little money but part way through the afternoon the Staff College’s Deputy Commandant, Air Cdre Joe Hardcastle, approached us and took us to a quiet corner where he told me that I was to be awarded the Air Force Cross in the forthcoming Queen’s Birthday Honours List. More champagne was needed!

So the year went slowly by: reading, researching, listening, writing, talking, playing all sorts of sports, mixing with other armed services, other nationalities and, whenever the possibility arose, making mischief for the staff. There was also lots of eating and drinking, sometimes formal but more often informal, and usually with international flavours. Like most courses, you get out of it what you put in. My rule for such events has been to always act the student. Don’t moan, it’s a waste of time as nothing will change, at least not while you are there, and turn up when and where you are told to. Most of all, take advantage of the time out from responsibilities – they’ll soon come back in abundance once you have graduated and been posted to your new ‘career-enhancing’ job.

November brought a very special day. It was the same day as the Queen and Prince Philip’s wedding anniversary that Linda and I attended the investiture at Buckingham Palace so that HMQ could pin a shiny new Air Force Cross on to my best uniform. So we got aboard my yellow Triumph Stag and drove into central London, down the Mall, up to and, after showing our invitation cards, through the wrought-iron gates into Buckingham Palace. We were directed to park in the central courtyard and then made our way to the entrance that we had seen so often on TV. Once through we were fairly unceremoniously split up. I was directed to a long corridor where there was gathered a large number of people representing a good cross section of the British population.

There I met up with one of my fellow course members, Colin Thirlwall, who was also to receive the Air Force Cross. A very well-dressed gentleman was patrolling the corridor with a sheaf of papers in his hand. His duty was to arrange the throng into some semblance of the right sequence. Colin and I soon learnt that we would come well down the pecking order.

When that was done we received the briefing as to procedure. At this point a minion took our RAF hats. I’m glad I didn’t invest in a new one, I thought.

‘Don’t worry you’ll get them back before you leave,’ the minion assured us. I would hope so; I’m sure that HMQ is not into nicking officers’ headgear!

The investitures took place in the ballroom and the next corridor we entered gave direct access. Much ‘shushing’ went on up ahead, which must have meant that things were now under way. We then shuffled spasmodically down the corridor with not much to amuse us, other than some rather grand pieces of artwork hanging on the walls. Eventually the corridor made a sharp right turn and over the heads of the folk ahead I could see the doors to the vast space of the ballroom.

I now had to remember the briefing. When the recipient ahead moves forward to receive their honour or award I had to move to the edge of the stage and wait. Another minion there would then give me the nod to walk smartly forward until I was abeam Her Majesty. Then a left turn and step forward until I was within pinning distance. Got it!

Before I knew it I was on my way. I was terrified that my leather-soled shoes (Oxford pattern, RAF officers for the use of) would slip on the well-polished ballroom floor. So, perhaps a little gingerly, I made my way into place. There I was greeted by a smiling monarch with a gentle handshake. She asked me a couple of apposite questions; she obviously had been well briefed but also had an impeccable memory. She then fixed the medal in place, offered her hand in congratulation and gently pushed me back to give the hint that I could go. Three steps backwards, right turn, marching off to be met at the opposite door by yet another minion who quickly unclipped my gong and put it in a box.

Linda was in the ballroom watching, but I never got the chance to look for her. Now we had to wait until the whole thing was over, so Colin and I loitered in yet another corridor for our spouses to appear. Soon we were reunited with them and our hats and made our way out into the courtyard where a huge amount of milling about and photography was going on. We declined the no doubt extortionate professional snapper; Linda was quite an accomplished photographer and that would be good enough for me. Of course, from that day on people would ask me the question, ‘What did you get that medal for?’ I don’t really have an answer. If there was a citation I had not seen it, so I could only guess that it was for eight years’ continuous service as a test pilot in Her Majesty’s Royal Air Force. I had done some high-risk stuff, as well as some classified things, and had not broken any aeroplanes on the way.2 It was a tremendous honour to receive the AFC and a wonderful experience to do so from the hand of a reigning monarch.

At about that time my posting notice arrived. I was going to some job in the Ministry of Defence Main Building in Whitehall, London. The job had several initials and a couple of numbers. However, before I could find out what it was, it changed! Two days later I was told that I was now posted to something called the Strike Command Briefing Team at High Wycombe, north-west of London. The location suited me much better as, at less than 30 miles from my home in Oxford, it was easily commutable by car. But the clue in the name did not give much feeling for the job. Briefing whom and on what?

So 1984 ended on a great note – George Orwell had got it very wrong! I had married a wonderful lady, I had rediscovered my Christian faith, I had received a prestigious award and it looked like I had a good job coming, albeit on the ground. Most importantly, I was looking forward and not back. Life really had begun (again) at 40! But what did the future hold?

1. The full story is related in my book Follow Me Through (The History Press, 2013).

2. The Air Force Cross is one of the highest awards in flying and was then officially awarded for ‘an act or acts of valor, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying, though not in active operations against the enemy’. It has since been changed to a peacetime award for a single act of outstanding courage and skill while flying.

2 THE BRIEFING TEAM

Yet again I started an RAF appointment just one week before Christmas! On 17 December 1984 I reported to RAF High Wycombe, the headquarters of the RAF’s highest-level operational formation, Strike Command, to discover just what I was in for over the next three years. After completing all the usual reams of personnel paperwork I was directed to a large brick building, constructed as a hollow square and known as ‘B Block’; ominous echoes of incarceration crossed my mind. There on the top floor I followed instructions to the three rooms occupied by the Command Briefing Team (CBT). I first met the boss, a very young-looking wing commander called Phil Sturley, then I was introduced to Peter, the man I was replacing; he was leaving on promotion to take over the reins of No. 51 Squadron.

The next introduction was to my office companion and co-worker, John Thomas, who was a squadron leader in the RAF’s administrative branch. John was a Geordie1 and I would soon learn that his Tyneside humour would keep our spirits up when the going got tough. The final member of the team was a female RAF corporal called Jan, who gave lots of sterling support and supplied tea and biccies to order, as well as all the stationery.

It took most of the week to discover what I would have to do as the junior GD2 member of the CBT. Most of the time John and I would be producing written briefs for the Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) or his deputy covering a range of topics. The most often required would be for changes of command at RAF Strike Command stations (air bases). Then there were briefs to be prepared for visiting VIPs who would be received by the C-in-C or his deputy. Sometimes we would have to produce briefs for the chief’s visits to other locations, especially commercial or military ones. Phil Sturley’s prime duty was to give audio-visual presentations to visitors, tailored to their areas of interest. I was Phil’s deputy for this task, and covered his leave or sickness. Finally, I would occasionally have to produce short briefings for the C-in-C using the in-house TV system; the whole HQ could watch these – so no pressure then!

As if that wasn’t enough, John filled me in on one more thing that the boss had not mentioned. During the regular, but thankfully not too frequent, war simulation exercises it would be our job to prepare and give TV or written briefs on the latest situations as supplied by the intelligence folks. John said that he would do the written stuff if I went on TV! A fair deal that I accepted with alacrity.

So I went off for my Christmas leave with all this rattling around in my head. I had by then discovered something about the command structure within the HQ, although I still had to meet most of the principals. The C-in-C was Air Chief Marshal Sir David Craig, a tall, dark-haired, distinguished officer, and his deputy was Air Marshal Sir Joe Gilbert. The man I would have contact with in the C-in-C’s office was his personal staff officer (PSO), Gp Capt Peter Squire, a pilot who had led his Harrier squadron with distinction during the Falklands War. He was also a previous commanding officer of the CBT, so he knew all the wrinkles and the excuses! We worked in the Plans Division and were collocated with all the various elements of that discipline on the top floor. The man in charge of planning was Air Cdre Mike Stear: an officer with a rugby forward’s build, an outwardly stern demeanour and, as I would soon learn, a relentless work ethic.

These important figures aside, I soon learnt that the most important people to keep on-side were the lovely ladies of the typing pool, this still being the era before desktop PCs. They were all gathered in one large room on the opposite side of the hollow square, one floor down, and we often had visual and aural contact through open windows across that space. It seemed, at times, to be John’s favourite pastime!

As 1985 progressed I got used to the sometimes frenetic pace of work, the requirements for briefs often mounting up faster than the two of us could churn them out. Gathering the information was a major part of our lives and we could often be seen buzzing round these particular corridors of power at high speed with papers under our arms. If any of the staff officers spotted us coming doors would slam, phones picked up or early lunches suddenly taken. They knew that we’d be interrupting them and nobody likes interruptions! But I soon worked out cunning ways to trap the unwary, like walking quickly past the target office door and then making a U-turn and catching the poor occupant as he relaxed. There were a good few people on the staff that I already knew: a couple of ex-fellow course members from Staff College and a handful of guys I’d met on previous tours.

Perhaps the most interesting, but also most demanding, work was doing TV briefings. The staff in the TV studio, which was based in the old Bomber Command underground bunker, were extremely helpful. I learned how to make my own autocues, using strips of paper stuck together with sticky tape. Occasionally this simple device would let me down by the tape unsticking, so I always had a script to hand. I also learnt the TV presenter’s trick of moving one’s head but still scanning the words on the autocue. This stopped the goldfish effect of the rigid head and moving eyes variety! I combed all sorts of military publications and the HQ’s photographic library for suitable illustrations, which could be projected full screen or ‘over the shoulder’. All in all, the TV studio was a well-run professional outfit – at least until I got in there. It was primarily used for a daily morning briefing, with one wing commander staff member employed to do that job. There was a sound feed from the C-in-C’s office so that he could ask questions. Thankfully he rarely did. I was only an occasional user of the TV system, but still had to prepare all the material and have at least one rehearsal before transmission. This was not something that I had ever expected to be doing.

An unexpected benefit of this, and the occasional audio-visual presentations I gave to visitors, was that the C-in-C knew me by sight. RAF High Wycombe had a splendid rule for the staff of all ranks that allowed us, nay told us, to walk around the station hatless or, as we Yorkshire folk have it, ‘baht t’at’. This made life much easier as we did not have to be giving or returning salutes every five paces. However, I was out and about one day, on a quest for material for yet another written brief, when I spotted a tall, distinguished, dark-haired officer walking towards me. It was the Commander-in-Chief.

As we passed (I think he was on the way to the station barber’s shop) the resistance I had to apply to my right arm to stop it shooting up was immense; I swapped my clipboard to my right hand to prevent it saluting.

‘Good morning sir,’ I said with a smile.

‘Good morning, Mike,’ he replied returning the smile. It was a bit of a shock for such a lofty ranking officer to address me by my first name, but I realised that it was soon after my first TV appearance. So my performance could not have been too bad – and even very senior officers feel that they know people they have seen on TV!

The headquarters was not just that of the RAF’s prime operational formation, but also the headquarters of the UK’s military aviation contribution to NATO; hence it was also known in NATO-speak as HQ UKAIR. So Sir David Craig also held the NATO title CINCUKAIR, and many of his subordinates were similarly ‘double-hatted’. That had the knock-on effect of making it important for all of us in the CBT to ensure that we understood all the implications of the NATO element and so would reflect the correct emphasis and terminology in our briefings, especially to visitors from allied nations.

In July 1985 RAF High Wycombe held its Summer Ball in the Officers’ Mess. One of our neighbours in Oxford was a single USAF pilot based at RAF Upper Heyford. We invited this dashing young officer to escort Linda’s daughter, Melanie, to the ball – with the proviso that he drove us all there in his handsome, growling, black Chevrolet Corvette.

After we had arrived at the Mess and had started our initial exploration of the various diversions for the evening, our chauffeur was walking around in his USAF mess kit with Melanie on his arm, in an open-mouthed state of wonderment. As we headed for the seafood bar, the traditional starting point of any Summer Ball, I spotted the C-in-C, his deputy and their wives coming towards us. Sir David spotted me and said, ‘Good evening, Mike. Splendid isn’t it?’

I, of course, agreed with him as his party passed by.

‘Gee, is that CINCUKAIR?’ said our American companion with awe. ‘And he knows your name?’ I remained modestly silent.

Not many weeks after I had arrived and was just about getting to grips with the job, Phil Sturley invited me into his office. He enquired as to how I was finding it.

‘Well, it is quite demanding and, at the same time, fascinating to be working in the headquarters, but not stuck with one specialised field like most other people.’

He agreed with my analysis and then said, ‘Well, Mike, I’ve got management to agree that this appointment is on a par with a personal staff officer’s job in terms of workload and responsibility. That means that your three-year tour here will be cut to two – good news, eh?’ I readily agreed; one year less to wait for a possible return to flying was certainly good news.

Although it was demanding on time and talent, the job was a fascinating way to find out, at first hand, about all the wide-ranging activities undertaken by the RAF’s Primary Command, still in its Cold War posture. Indeed the major work going on within the very secure grounds of the HQ was the construction of a new, advanced and nuclear strike-proof underground bunker – yet another thing to learn about. The visitors that came to the HQ were many and varied. On one occasion the head of the People’s Army of the Chinese Republic, another time the French chief of the Armée de l’Air and then, later, NATO’s outgoing Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR). Then there were visits from politicians, captains of industry, the press and foreign defence attachés. All of these had to have tailored briefings. Every outgoing Strike Command station commander came for his end-of-tour debrief with the C-in-C and a written brief had to be prepared, including any future plans for the station. Our friends that shared the same corridor used to be particularly helpful in this. If we could rope them in, it was all go!

While I was at home, taking a spot of leave tacked on to the Easter weekend, the phone rang.

‘Hello.’

‘Good morning, Mike, it’s the boss. I’ve got some news for you that I thought I you should hear straight away.’

‘Good news or bad news?’ I asked.

‘Well, there’s good news, good news and good news,’ he replied, somewhat enigmatically.

‘Well you’d better give me the good news then!’ I said, mystified by this triple good fortune.

‘First, you will be leaving us in August – that’s more than a year earlier than expected. Second, you are going to be promoted to wing commander and, third, you will take over as OC Flying Wing at the Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough.’

I could hardly believe my ears – all that and now less than six months more writing and presenting to do. I could already sense that the summer would pass slowly because of my impatience to get back to flying.

One of the first thoughts that crossed my mind was that, as OC Flying at Farnborough, I would get to fly the SE.5a First World War fighter that was jointly owned and operated by the RAE and the Shuttleworth Collection of historic and vintage aircraft. This was something I had wanted to do ever since I sat in it on the ground during my first tour there in the late 1970s. But, of course, there was so much more in store. I couldn’t wait!

1. For those readers not familiar with this nomenclature, ‘Geordie’ means someone from the north-east of England, usually the environs of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

2. GD means General Duties and indicates a member of the aircrew and operations branch of the RAF.

3 AIRBORNE AGAIN

During my time at the RAF Staff College and HQ Strike Command I had not remained totally tied to the ground. I had gone along to No. 6 Air Experience Flight (AEF) at RAF Abingdon,1 not far from our home in Oxford, and got myself ‘on the books’ as a staff pilot flying, yet again, the dear little de Havilland Chipmunk. In that part-time capacity I gave the air cadets twenty-minute flights to try to instil in them an appreciation or even a love for aviation. Perhaps it was a lofty ambition, but many of them seemed to enjoy the experience; just a few spent most of the time shouting into a sick bag! My attendance at Abingdon was mostly at weekends, although I was able to take an occasional afternoon off and ‘slip the surly bonds of earth’.2

Then in June 1985 an old friend and colleague from Radar Research Squadron days, now retired RAF navigator Peter Middlebrook, contacted me to see whether I would be willing to go with him to view and test fly a Piper Cub that he was hoping to buy. I readily accepted and the following weekend we and our ladies travelled to a small airstrip in Suffolk to look over the high-winged 1940s American flying machine. It was a pretty little thing and appropriately registered G-OCUB! I had flown a Cub before on a few occasions and, after Peter had flown with the vendor, I took to the air with my wife; this was the first time we had flown together. Everything seemed to work as advertised, not that there was a lot that could go wrong with such a simple aeroplane. It handled like it should and flew in trim. The only small problem was that, being a hot summer’s day, the windows on each side of the tandem seats had been removed and that gave Linda a feeling of extreme insecurity, especially when we banked to turn. Then she remembered how much effort had been applied to get her into the front seat in the first place, so she relaxed a bit. Well, at least until I asked her if she could see the airstrip as I pretended that I had no idea where we were!

The upshot of all this was that Peter bought the Cub and we flew it back to Oxford Kidlington airport, where he had arranged to keep it. Over the next two months I began to teach him to fly it. The quid pro quo was that I could use it any time I wanted to – I just had to put the petrol in. So the summer weekends during my very short tour at High Wycombe still contained an element of aviation, albeit in light aircraft.

However, all that was invisible to the Royal Air Force. As far as they were concerned I hadn’t flown a ‘real’ aeroplane for at least eighteen months. So I had to attend a fast-jet refresher course, flying the BAe Hawk trainer at RAF Brawdy in south-west Wales. And that was fine by me.

Brawdy airfield was on the far-west Welsh coast, not far from the cathedral city of St David’s, the patron saint of Wales. Brawdy’s major claim to fame was its ‘forty-knot fog’, caused when the moist air blown in from the southern Irish Sea was thrust up and over the cliffs just off the end of the main runway. In the right, or should that be the wrong, conditions, the increase in height of just a few hundred feet was sufficient for the moisture in the air to condense and form a cloud that lay on the ground – in meteorological terms, advection fog. In good weather Brawdy’s coastal location gave its squadrons easy access to a nearby weapons range, the UK Low Flying System and lots of airspace for manoeuvring over the sea. The course that I was to join used the Hawk to get us ex-‘ground-pounders’ back up to speed. The Hawk had first flown in August 1974 and entered RAF service two years later. It replaced the Folland Gnat and in 1979 was then adopted by the RAF Aerobatic Team – the Red Arrows.

I had flown the Hawk during 1983 at Boscombe Down so it wasn’t entirely new to me. The Hawk is a delight to fly, with excellent stability and control characteristics, especially during rolls; you can easily stop a maximum rate roll precisely, with no perceptible ‘wobble’. The maximum speed performance of the Hawk is a little down on the Gnat and its company predecessor the Hunter, but its economy of operation is much better than both. The biggest improvement was in the ‘office’. The cockpit was well designed with everything in the right place and the field of view was first class. It was one of the few aircraft I had flown in which I didn’t have to raise the seat to its highest position; I have very short back.3

I arrived at RAF Brawdy at the beginning of September 1985, after what felt like a very long drive from Oxford, and took up residence in a well-worn room in the rather utilitarian Officers’ Mess. After the usual week of preparation, with ground school and simulator rides, I was deemed knowledgeable enough to start flying again. However, my first two flights were in a Jet Provost – the JP that I had trained on twenty-two years earlier! There were two or three of these at Brawdy, specifically for training forward air controllers; to this end they were finished in a camouflage paint job. But it still didn’t make the little JP any more aggressive! As it turned out, one of the JP pilots was an ex-Canberra student of mine, Flt Lt Dave McIntyre, and he had picked up the job of taking a JP to the Battle of Britain Air Display at RAF Abingdon for the weekend.

As Abingdon was just a stone’s throw from home, I asked if I could go with him and be his batman for the day. He readily agreed; and that was nothing to do with me now wearing my wing commander’s rank tapes! Linda met us in the static aircraft park and we spent the day at the air show before spending the rest of the weekend together. What bliss, and I didn’t have to drive to the far end of Wales on Sunday night.

My flying in the Hawk started a couple of days after I returned to Brawdy. After two dual sorties I was sent off on my own. It was a sheer delight to be back in a manoeuvrable jet, doing aerobatics and just enjoying the freedom of the skies. When I got back my instructor, Flt Lt Burkby, said to me, ‘You enjoy your flying, don’t you, sir?’

I readily agreed but silently wondered how he knew.

He soon let on. ‘I watched your take-off from the tower,’ he said, somewhat enigmatically. I said nothing but I supposed that my usual Canberra and Buccaneer style of ‘get the gear up quickly and hold it low’ was perhaps a little out of the ordinary for the ‘students’.

The course progressed and included a few days at Linton-on-Ouse in Yorkshire to escape the ‘forty-knot fog’. I was also allowed to drop bombs (little ones) and shoot bullets, as well as fly some one-on-one and two-on-two air–air combat sorties.

It all came to an end too soon, exactly one month since I had arrived; I had flown a total of twenty hours in as many days. I had thoroughly enjoyed myself and felt up to speed, so I got back into my car and drove back to Oxford with a huge smile.

I was only there for the weekend because on the Monday I had to drive in a different direction to report to RAF Shawbury for my helicopter course. The last time I had been there, in 1979, I had learned to become a pilot of those airborne threshing machines, flying the venerable Westland Whirlwind. Now, six years later, the ‘Whirlybirds’ had been consigned to scrap or museums and were replaced with a little sports car of a helicopter – the Gazelle.

I had been very fortunate in my earlier flying career to have been in a post where I could fly fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft during the same tour of duty.4 As I would again be commanding flight-test units with both classes of aircraft, I had persuaded the powers that be that it was essential I flew helicopters in my new post, and they had readily agreed. However, they had only given me three weeks to complete the eighteen-hour syllabus. So no pressure then!

Flying helicopters is similar but different to flying aeroplanes. I liken the difference to that between motorcycles and motorcars. The helicopter, like a motorcycle, requires more attention to balance and is essentially ‘flying’ even on the ground once the blades are turning. The ‘stick’ looks like the one found in an aeroplane and it does still raise and lower the nose. But the other control, the collective lever, is unique to rotorcraft and that essentially controls the vertical movement of the machine. In conjunction with use of the stick, it also controls forward speed. So quite a different skill set is needed. And that’s even before you learn to hover.