Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Catch a rare glimpse into the training of the nation's defence personnel, as pilot turned flying instructor Mike Brooke shares with us some of his amusing firsthand flying stories. After his success as a Cold War Canberra pilot, Mike was dispatched to become a flying instructor at the Central Flying School in the 1970s. 'Follow him through' – as he would instruct his trainees – as he experiences the quite literal ups and downs of teaching the Glasgow and Strathclyde Air Squadron. Discover how he battled the diminutive de Havilland Chipmunk in order to teach others how to fly the aircraft, before finally moving to instruct on the Canberra in its many marks. Here Mike will take you on a quite often bumpy journey as an instructor of pilots old and new, recounting tales of flying, near accidents and less serious incidents that flying these old but still demanding aircraft bring. Following on from his debut book, A Bucket of Sunshine, Mike continues to use his personal experience to bring aviation to life, proving indispensable for any aviation enthusiast.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 421

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For my mum Lorna, my wife Linda and all our children and grandchildren

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Prologue

PART ONE: THE CENTRAL FLYING SCHOOL

1 Chipmunks?!

2 Learning to Fly Again

3 Learning to Talk Again

4 A Country Life

5 Spectator Sports

6 Graduation

PART TWO: GLASGOW & STRATHCLYDE UNIVERSITY AIR SQUADRON

7 And I’ll Be in Scotland Afore Ye

8 The Real Thing

9 Summer Camps

10 Reorganising and Removing

11 Living in Glasgow

12 Journeys South

13 Flying Coppers, Flying Trophies and Moving On

14 In Retrospect

PART THREE: CFS (AGAIN!)

15 Pretending to be Bloggs

16 Weather or Not

17 Skylarking About

18 Problems, People and Pelicans

19 Extra Curricular Activities

20 What Next?

PART FOUR: THE CANBERRA OCU (AGAIN!)

21 Back to the Future

22 Not Moving On

23 Interesting Times

24 Trips Away

25 Profits, Coffees and The Thursday War

26 Thinking About the Future

27 Disaster Strikes

28 Grounded

29 Flight Safety

30 A Silver Anniversary

31 Licensed to Trap

32 Back to School

Notes

Appendix: Cockpit Illustrations

Glossary of Abbreviations

Plate Section

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

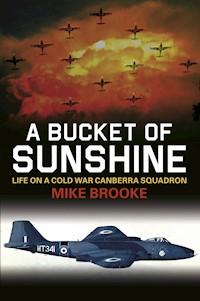

Writing an autobiographical book is an absorbing pastime. Like a good day’s fishing it takes one away from the everyday cares of life. It also takes one back to the sunlit uplands of one’s youth, where the ravages of time and old age are still far in the future. My wonderful wife Linda has already been through this process with me once during the three months that I was writing my first book: A Bucket of Sunshine. Then she would lose me to my study for hours on end, while I regressed to the years of my childhood and early twenties. Now I have repeated the exercise and, once more, she has been my proof-reader, editor and critic. After all, she did such a good job on my first volume, how could I refuse her the chance to do it again? And she did so with consummate skill, patience and alacrity. I cannot thank her enough. As always she is the wind beneath my wings.

Thanks must also go to Matt Savage of Mach One Manuals in Australia (www.mach-one-manuals.net) for letting me reproduce the cockpit photographs that appear in the Appendix. And to Ray Deacon for his permission to use the Canberra PR9 photographs that he provided; credits are given with the captions. I also sincerely thank all the folk at The History Press who have been brave enough to take me on again. I hope that you will agree with me that they have done another great job in the production of this book.

And last, but by no means least, I want to sincerely thank Air Vice Marshal Gavin Mackay for writing the Foreword to this book and providing so many great photographs of those far-off, fun-filled days in Glasgow, when we were both much younger!

FOREWORD

‘Date: 5 January 1967. Aircraft: Chipmunk WG431. Captain: Sqn Ldr Etches. Pupil: Self. Exercises: Effects of Controls, Taxying, Straight & Level. Dual: 1 Hour.’

Even now, more than forty-six years later, seeing the logbook entry of my first sortie as a new and very excited cadet pilot on the Universities of Glasgow and Strathclyde Air Squadron (UGSAS) makes my heart beat that little bit faster and brings memories flooding back.

I was studying Civil Engineering at Glasgow University. My future lay in bridges, buildings, roads and dams, with McAlpine, Wimpey, Taylor Woodrow or the like. That plan did not long survive my encounter with UGSAS and its members, brought so vividly to life in this book about Mike Brooke’s time as a Qualified Flying Instructor (QFI).

There was the CFI, George Etches, who always wore a multi-coloured ‘terrorist-chic’ balaclava under his bone-dome on test sorties, to disconcert the over-confident and divert the nervous; the fearsome Hamish Logan, whose leadership of late night sessions in the bar spawned the squadron catchphrase ‘Logan Must Go!’ (to bed earlier); Andy Bell, my primary instructor, who kept me spellbound with tales of Hunter ground attack ops in Aden, and whispered in my ear that (as the USAF so succinctly put it), ‘If you ain’t single seat – you ain’t sh*t’; John Greenhill, the fatherly Boss; Heck Skinner, a couthie fellow Highlander; Colin Adams, the epitome of smooth; and Ian Montgomerie, the aesthete, who landed one hot day on Summer Camp to confide that opening the canopy and holding cupped hands aloft in the 100 knot breeze was ‘just like fondling bosoms’ – sparking a squadron scramble airborne to investigate the phenomenon. And then there was Mike Brooke himself: a cherubic dynamo of enthusiasm for all things related to flying and the RAF; a staunch champion of English (specifically Yorkshire) attitudes and values in a chauvinistically Scottish squadron; a talented artist, whose anthropomorphic cartoons of aeroplanes still hang in the CFS Elementary Squadron crew room; and a natural leader-astray of cadet pilots. Small wonder that I and several of my contemporaries were quickly seduced away from our intended ‘respectable’ civilian careers as engineers, lawyers, scientists or teachers. I never looked back, and I owe Mike and his colleagues a huge debt of gratitude for setting me on the path to becoming a fighter pilot.

Like its predecessor, A Bucket of Sunshine, this book covers a great deal more than Mike Brooke’s progress through a particular phase in his RAF service. The reader will emerge with a working knowledge of how to fly a Chipmunk, including landing by night on a flare-illuminated grass strip, recovering from a spin, coping with the perils of carburettor icing, and the art and science of the eight-point roll (thanks Mike!). There are also some top tips on piloting the Jet Provost, the Gnat, the Meteor and, of course, the Canberra – including the dreaded simulated asymmetric approach, which probably claimed more lives than the real thing. More generally, you will find vignettes on the Smith-Barry method of flying instruction used by CFS, the different types of fog affecting aviation, wake turbulence, un-pressurised high flight and the ‘bends’, electronic counter-measures (ECM), and how to land safely – or not – at Gibraltar. Seasoned with some suitably disreputable jokes, it encapsulates just about everything one needed to know to be an RAF pilot in the ’60s and 70s.

I am quite sure that you will enjoy this book as much as I did. For the military aviator, it will revive many memories of the ‘I did that’ variety. For the interested amateur, it will provide some fascinating insights into RAF life and flying operations of the time. For everyone, it promises to be a thoroughly good read, told at a cracking pace in a straightforward and engaging style, typical of the Mike Brooke I came to know as our paths crossed and re-crossed in the Service. Savour it best by transporting your imagination to a ‘Black Flag’ day, when the promised 10 o’clock weather clearance has failed (yet again) to materialise, but the Boss hasn’t yet summoned up the nerve to call a squadron ‘Stack’ for the afternoon. Clear away the Uckers board, get one of the JPs (junior pilots) to make you a NATO standard coffee (or a ‘Witch’s Tit’ if you prefer black, no sugar), sink into that battered armchair in the corner, and off you go, solo.

Air Vice Marshal Gavin Mackay CB, OBE, AFC, BSc, FRAeS, RAF (retd)

INTRODUCTION

Wing Commander Michael C. Brooke, AFC RAF (retd)

Mike Brooke was born in Bradford, West Yorkshire on 22 April 1944. After a grammar school education he joined the RAF in January 1962. Subsequent to passing through all-jet flying training as a pilot he was posted to No 16 Squadron in RAF Germany, where he flew the Canberra B(I)8 in the low-level, night interdictor, strike and attack roles.

On completion of this tour he was selected for the RAF Central Flying School course where he was trained as a Qualified Flying Instructor. Three flying instructional tours followed then, in 1975, Mike attended the Empire Test Pilot’s School (ETPS) and graduated as a Fixed Wing Test Pilot. After graduation he spent five years as an experimental test pilot at the Royal Aerospace Establishments at Farnborough and Bedford, at the latter commanding the Radar Research Squadron. At the beginning of 1981 Mike returned to ETPS as a tutor, where he spent three years teaching pilots from all over the world to be test pilots. In 1984 Mike was awarded the Air Force Cross (AFC) for his work within the flight test community; HM Queen Elizabeth II presented the medal to him at Buckingham Palace in November that year.

After attending the RAF Staff College’s Advanced Staff Course he spent six months at HQ Strike Command, where he was a member of the Command Briefing Team. In 1985 Mike was promoted to Wing Commander and given command of Flying Wing at RAE (Royal Aircraft Establishment) Farnborough. A wide variety of aircraft came his way, including helicopters such as the Gazelle, Wessex and Sea King. After three years at Farnborough, he returned once more to Boscombe Down, this time as Wing Commander Flying, in charge of all flying support activities and deputy to the chief test pilot.

In 1994, at the age of 50, Mike decided to take voluntary redundancy. He then spent five years in part-time aviation consultancy, working as a test pilot instructor with the International Test Pilots’ School, Cranfield University and as a developmental test pilot for the Slingsby Aircraft Company.

In 1998, Mike moved to Texas to fly for a company called Grace Aire, who aimed to give flight test training in their ex-RAF Hunter jet trainers, gain US Department of Defense flight test contracts and display the Hunter at air shows. Sadly, the company went into liquidation after two years so Mike returned to Europe, choosing to live in Northern France.

In January 2002, he returned to RAF service as a full-time reservist pilot, commanding one of the RAF’s eleven Air Experience Flights, which give flying experience to members of the UK’s Air Cadet Organisation. He finally retired from the RAF in April 2004, on his 60th birthday. Mike has flown over 7,500 hours (mostly one at a time) on over 130 aircraft types, was a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society, a Liveryman and a Master Pilot of the Guild of Air Pilots and Air Navigators, is a Freeman of the City of London and is a Fellow of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots. He also flew many historic and vintage aircraft with The Shuttleworth Collection, The Harvard Team and Jet Heritage.

This book is a mainly humorous insight into the life of an RAF Qualified Flying Instructor (QFI) at three levels: on a University Air Squadron, at the RAF’s Central Flying School and with the Canberra Operational Conversion Unit. There are, literally, many ups and downs in this tale with both humour and fear on show. Student pilots will do the most unexpected things at times and Mike pulls no punches in telling his tale.

Mike is married to Linda, they have four children and seven grandchildren. They live in France where they have restored a 230-year-old Normandy farmhouse and created a garden from a field. Mike is a licensed lay minister in the local Anglican church, which he and Linda helped to found in 2003. Linda is following in his footsteps and training for the Lay Ministry in the same church.

PROLOGUE

It is the middle of June 1962. I am 18 years old. Instead of doing what many of my erstwhile teenage school friends are doing: hiking or rock-climbing in the Yorkshire Dales, motorcycling, fishing or just hanging out in a coffee bar, on the constant lookout for female companionship, I am sitting in the left-hand seat of a dual-controlled jet aeroplane over 2 miles above those self-same Yorkshire Dales. I am there because at the beginning of the year I joined the RAF and now I am training as a pilot.

My instructor is about to teach me my first aerobatic manoeuvre: a loop. He first demonstrates one. I sit still, all eyes and ears, with a soupcon of trepidation and a frisson of excitement disturbing the usually lifeless butterflies in the pit of my stomach. In the right-hand seat Flight Lieutenant Wally Norton, who I must address as ‘Sir’, dives the aircraft, a Jet Provost Mk 3, to over 200kts and then pulls it vertically upwards, imposing a load of three times the force of gravity on our bodies. The far horizon that I can see through the windscreen ahead of me disappears downwards. All I can see now is blue sky. A few seconds later the horizon reappears, but this time at the top of the windscreen. I look upwards and see downwards to the wide panorama of my native Yorkshire countryside, laid out a little disturbingly above my head. The G-force and airspeed have both reduced markedly, but the nose of the aircraft continues to rotate and we are soon headed vertically downwards. The speed is increasing and I am forced back down into my seat as Wally pulls out and the world is once more back where it belongs.

‘Well, me lad, what did you think of that?’

A little breathlessly I say, ‘Amazing, sir!’

‘OK. It’s time for you to have a go. Follow me through.’

I place my right hand on the control column; that’s its formal name – real pilots call it ‘the stick’. I put my left hand on the throttle. I push my feet forward and rest them lightly on the rudder pedals. Wally and all the other instructors that I will fly with over the next two years, and who will teach me to fly ever faster and bigger jets, use this well-established routine of demonstration, instruction and practice.

I will spend most of the next forty-two years flying aircraft of many different types, in many different places. I will even spend a good few years teaching others to fly and, in doing so, would find myself frequently saying, ‘Follow me through.’

PART ONE

THE CENTRAL FLYING SCHOOL

He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches.

George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman (1903), ‘Maxims for Revolutionists’

1 CHIPMUNKS?!

After all my training was complete, in May 1964, I was posted to my first operational tour of duty with No 16 Squadron at RAF Laarbruch in West Germany. There I flew the Canberra B(I)8 in the low-level, day and night, nuclear strike and conventional attack roles. It was an exciting time.1 The Cold War was at its height, I was on the RAF’s front line operating a flying war machine, regularly at low-level, which meant at less than 100 metres from the ground, practising bombing and shooting and being ready to react to any Warsaw Pact aggression with a nuclear weapon-loaded aircraft. It was the best of times and it was the worst of times. And there were possibilities for even more stimulating times ahead for any young man who enjoyed that sort of flying.

After only six months on the squadron I was offered the exciting possibility of moving on, two or three years later, to the supersonic, low-level strike and reconnaissance aircraft known as the BAC TSR2. However, within another six months, that option became null and void when the Labour government cancelled the project. But all was not lost. To replace the annulled TSR2 option the government announced that it would purchase the American General Dynamics F-111 swing-wing bomber. I was told that my posting would then be extended so that I could go to the USA to train on that revolutionary aircraft. However, within another year both of these proposed replacements for the Canberra had been cancelled. Further cuts and changes of mind by the Ministry of Defence then put all the low-level, tactical strike/attack eggs in the Blackburn Buccaneer basket; an aircraft originally built for the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. But that decision came too late for me.

By early 1967 I had instead been offered an accelerated captaincy on the Vulcan bomber; but that did not attract me at all. I wanted to fly something fast and exciting. So I decided instead to volunteer to attend the Central Flying School (CFS), based at RAF Little Rissington, in Gloucestershire, where I would be taught to be a flying instructor. In May 1963, at the end of my basic flying training course, I missed the opportunity to join the first advanced flying training course on the new Folland Gnat trainer. That course had been shelved as the Gnat’s introduction into service had been delayed. Instead I had been sent to fly the almost obsolete, 1940s designed, De Havilland Vampire. So, in early 1967, seeing another opportunity to fly the Gnat, a diminutive but sharp-pointed, swept-winged aeroplane, I asked OC No 16 Squadron to endorse my CFS application with a recommendation for me to join the Gnat element of the course as a student flying instructor. This he had done with both alacrity and a pen.

Before I left Germany a large packet of forms arrived in my mailbox. It contained lots of information about the various CFS courses, plus an abundance of forms to be completed and returned soonest. As I read them I found that most were about University Air Squadrons (UASs) and the need for their instructors to volunteer and, preferably, to have Permanent Commissions (PC). Although I had one of those I wasn’t the least bit interested in going to some far-flung part of the UK and flying the slow, pint-sized, propeller-driven De Havilland Chipmunk. So I diligently ignored all the UAS bumph and filled out the other required forms.

Eventually I received a posting notice to attend No 239 CFS Fixed Wing Qualified Flying Instructors’ (QFI) Course starting on Tuesday 30 May 1967. As my tour in Germany was due to finish on Friday 5 May I had over three weeks leave coming. I had married my wife, Mo, in July 1965 and she and I had lived in a rented flat close to the base in Germany. So it was first off home to Yorkshire for a while to see our parents and then south to RAF Little Rissington. At 750ft above sea level it was the RAF’s highest UK airfield, uphill from the well-known Cotswolds tourist trap of Bourton-on-the-Water. I was going to become a teacher!

When I moved from Germany back to England, away from the front line, the world was in the grip of the frosty geo-political climate that was the Cold War. Nuclear-armed NATO, led by the USA, was deployed across Europe in a Mexican stand-off with the USSR and its Warsaw Pact allies, also armed with weapons of mass destruction and superior numbers of conventional armed forces. The USSR was still suffering from the paranoia brought about through the loss of more than 20 million of its citizens during the Second World War, the conflict they called the Great Patriotic War. Much of that suspicion and mistrust was brought about by Hitler’s treacherous reversal of his non-aggression pact with Stalin by the ‘Operation Barbarossa’ invasion of the Motherland in June 1941. In the Europe of the mid-1960s there was a line drawn in the sand of the continent across which neither side dared venture.

To counter many perceived threats of the time the RAF had over 140,000 personnel and was spread across much of the old British Empire. There were four functional operational commands based in the UK: Fighter, Bomber, Coastal and Transport. Overseas there were operational squadrons in four geographical commands: Near, Middle and Far East and RAF Germany. To supply a regular corps of fully trained aircrew for these operational units Training Command had flying training schools based at ten airfields in the UK. The approximate annual requirement for pilots of all disciplines was over 400. Therefore in order to train these pilots there was a need for about 120 flying instructors per year. The Central Flying School would train all of these.

The RAF’s Central Flying School (CFS) is the oldest military flying training organisation in the world. It was founded in 1911 at Upavon on Salisbury Plain, in Wiltshire, training Army and Royal Navy pilots who would form the foundation of the Royal Flying Corps. The school’s development over the following decades eventually led to it becoming the single tri-service and Commonwealth unit for the specific training of Qualified Flying Instructors (QFIs). From Upavon the school moved several times in various guises before, in May 1946, it reformed at RAF Little Rissington, near Bourton-on-the-Water in Gloucestershire. By the mid-1960s the CFS had outposts at RAF Kemble, also in Gloucestershire, for Gnat training, and RAF Shawbury, in Shropshire, for helicopter training. Air forces of many nations send pilots to the CFS to gain the prestigious ‘QFI’ (or ‘QHI’ for helicopter instructors) qualification. The school also has a standardisation team that operates worldwide: they are known as Examining Wing or, more colloquially as Exam Wing, or sometimes, even more colloquially and most frequently, as ‘the Trappers’. Their role is to help standardise and, where necessary, improve flying instruction. The Trappers web extends even further into the RAF’s operational world through the appointment of CFS Agents, whose role is to check and maintain flying standards on the operational squadrons.

My course’s first day at CFS, towards the end of May 1967, was in keeping with the traditional RAF pattern. Go to the ground-school building, sit in a classroom and fill out a whole raft of forms; with, yet again, much repetition of name, rank and number. It was like being interrogated by paperwork! Then we were given various welcome chats by the Chief Ground Instructor (CGI), the Chief Flying Instructor (CFI) and finally the Commandant, a lofty, grey-haired and distinguished looking Air Commodore.

After being given a programme of ground studies for the next two weeks, we settled into the inevitable routine of classroom lessons on aerodynamics, meteorology, aero-medical sciences and all manner of things that we’d done before. The difference this time was that the subjects were dealt with much more rigorously. The reason given was that, as flying instructors, we were expected to know all this stuff in depth, as we would have to be able to explain any or all of it to our students.

We were a cosmopolitan bunch. There were guys from Australia, Canada, the Royal Navy and the Army on the course. Also among our number were three Arab pilots, but after a few days they disappeared. Saturday 5 June was the start of the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War. I’ve often wondered what happened to them.

Being under 25 years of age I wasn’t allowed to occupy Officers’ Married Quarters (OMQs) or a ‘hiring’,2 so I was living in the Officers’ Mess and planned to do so for a few weeks while I found somewhere suitable and affordable to rent privately. That helped me to gel more quickly with those course members who were in the same boat.

At the end of the first week the CGI came into the coffee bar at the mid-morning break and announced that there were two places for prospective University Air Squadron instructors that had not been taken up by volunteers. He then announced that student instructors Mathieson and Brooke would be allocated those places. I was so shocked that I chased him down the corridor as he headed back to the safety of his office and asked him if he was sure that he had got that right. He told me that indeed it was correct.

‘But I’m going to Gnats!’ I protested.

‘No you’re not, young fellah. The Gnat slots have all been filled. You are going to Chipmunks.’

I was astonished and my flabber was well and truly gasted. After lunch I went back to his office and in some trepidation, knocked lightly on his door. ‘Enter!’ he called out.

I then explained to him that I had applied to CFS specifically volunteering to fly the Gnat and that my application form contained a glowing endorsement from my squadron commander to that effect.

‘Supply and demand, old boy. You and Mathieson have Permanent Commissions and that is highly desirable for UAS instructors. Sorry but that’s the way it is.’

‘Would it be possible to see if I could find someone else who has a PC who would like to swap?’ I asked.

‘Yes, I don’t see why not. You obviously feel strongly about it, but I must know for sure before the end of next week.’

So I was now a man on a mission. I first talked to the Gnat candidates but, unsurprisingly, they were very happy bunnies and were not interested in my proposition. I then chatted with a couple of guys that I knew had PCs. They were on the Jet Provost course, but again I drew a blank. I went back to the CGI to tell him that I had failed in my quest and that I wanted to see whether I could be held over for the next course. He then surprised me by saying that he had spoken to the Commandant and that the great man was willing to listen to me. I rang his Aide de Camp and got an appointment for the next day.

I duly turned up at the Commandant’s outer office, best hat on, trousers pressed and shoes shone for the occasion. I was ushered in and found that I was immediately invited to sit and tell my tale. The Commandant listened attentively and gave me occasional encouraging but benign smiles. At the end of my monologue, giving him all the background, he said that he would get his personnel staff officer to see what he could do and that the latter would be in touch with me before the week was out. I stood, put my hat back on, saluted smartly and left, wondering how long I might have to wait for an answer.

It wasn’t long. By mid-afternoon I had been given the news that any pause in my training would not be looked upon kindly in the ivory towers, that is if it was even sanctioned, which I was told was most doubtful. I would most likely be given some menial ground post in some backwater, which wouldn’t do my career much good. I considered all this for a few moments and realised that I would rather be flying anything than being the Families Officer in the Outer Hebrides for a year!

‘OK,’ I admitted, ‘You win – I’ll carry on with the Chipmunk course and hope that I get to an interesting UAS.’

Having hoped to be flying the small, modern and fast jet trainer known appropriately as the Gnat, I really had not wanted to fly something old, slow and propeller-driven; even if it, too, was small.

So at the end of the second week half a dozen others and I moved down the flight line to the hangar where D Flight of No 3 Squadron, CFS and their fleet of Chipmunks operated. We found that we were next door to E Flight, who operated the twin-piston engined Vickers Varsity, on which the multi-engined instructors of our band of brothers would be trained. The rest of the course, numbering about twelve, was at the other end of the flight line with one of the two Jet Provost squadrons.

Over coffee we met the staff instructors, a formidable band of folk, many of whom seemed easily old enough to be our fathers. One such officer, a silver haired, bluff northerner, Flight Lieutenant Jack Hindle, picked me out and announced that he would be my instructor. I noticed immediately that he was wearing a rather ornate No 16 Squadron badge.

‘I’ve just come from 16 Squadron,’ I said. ‘What did you fly when you were on the squadron?’

With no hint of a smile, but a wicked twinkle in his eye he replied, ‘Westland Wapitis.’3 I thought that this was a curious answer because, as far as I knew, No 16 Squadron hadn’t operated Wapitis and, anyway, he wasn’t that old. However, I let it pass for the moment; it was just a taste of his wry northern humour. I discovered later that Jack had flown Hawker Tempests4 with No 16 Squadron, after the war. His experience had, along with that of a couple of other D Flight staff instructors, landed him a role in the Battle of Britain film, which had only recently been completed. He told me that he had been too well built and the wrong age to do the action shots of running out to the aircraft. He had just flown the Spitfires or Hurricanes for the aerial shots. Lucky chap! Maybe something good could come out of flying these little tail-wheeled trainers, I wondered silently. Maybe, one day, experience of operating a Chipmunk might lead to offers of flying bigger ‘tail-draggers’? But the next thing was more immediate: to start flying again and then learning to talk at the same time.

2 LEARNING TO FLY AGAIN

After a month or so I had found somewhere for Mo and I to live: a one-bedroom flat over an antiques shop on the edge of the market place in Stow-on-the-Wold. Our three rooms overlooked the local police station. I had also bought myself a 350cc BSA motorcycle for commuting the 5 miles to work, thus leaving our 1965 MG Midget for Mo to use. So, having unpacked the various boxes and cases that had arrived from Germany, we were soon settled into a new life as residents of a Cotswolds market town; a big change from my urban upbringing in West Yorkshire and our tiny flat in a small German village.

Back at work the course had now split into its separate specialist groups for even more classroom work. We Chipmunk operators were being acquainted with the mysteries of the Gipsy Major engine with its simple carburettor; valve lead, lag and overlap; twin magnetos and the four-stroke cycle, named after some chap called Otto – vorsprung durch technik?!5 Not all this technical content was completely new to me as, in my youth, I had dismantled and re-mantled motorcycle engines many times – much to the despair of my father when he wanted to get the car into the garage. A new thing, to me at least, was the fact that the engine, tiny though it was, had three levers to control it! Jets had just one: the throttle. You got more or less thrust simply by moving the single lever forward and back; the throttle controlled how much fuel went into the engine to be burned. Simple! But in the Chipmunk we had the throttle to control the power, the mixture lever to make sure that the ratio of air and fuel going into the engine was correct and the carburettor heat control lever to make sure that the carburettor didn’t ice up and restrict the amount of air going into the engine. As it happened we could almost forget this one as in RAF Chipmunks it was locked in the ‘hot’ position.

However, the way that a propeller works and mysterious associated terms like asymmetric blade effect, gyroscopic moment and blade slip were something totally new to me. I had gone through an all-jet-flying training system and had never laid hands on a piston-engined aircraft before. And this one had yet another new and probably challenging item – a tailwheel; all the jets I had flown had a wheel at the front – the nosewheel. I had heard that both take-off and landing in tailwheel-equipped aircraft were much more difficult tasks than in a nosewheel-equipped aeroplane. I wasn’t entirely sure why – but I’d soon be finding out!

The Chipmunk was designed to replace the De Havilland (DH) Tiger Moth biplane trainer that had been widely used by the RAF during the Second World War. A man rejoicing in the name of Wsiewolod Jakimiuk, a Polish engineer living in Canada, created the Chipmunk as the first home-grown design at DH Canada Ltd. The Chipmunk is an all-metal, low wing, tandem two-place, single-engine aircraft with fixed tailwheel undercarriage and fabric-covered control surfaces. A framed and glazed canopy covers the pilot/student (front) and instructor/passenger (rear) positions; this slides back to give both occupants access to their cockpits. CF-DIO-X, the Chipmunk prototype, flew for the first time at Downsview, Toronto, Canada on 22 May 1946 with UK-based DH Test pilot Pat Fillingham at the controls. The production version of the Chipmunk was powered by a 145hp (108 kW) four-cylinder in-line, DH Gipsy Major 8 engine. In 1948 two of the Canadian-built, but British registered, Chipmunks were evaluated by test pilots at Boscombe Down. There were no major problems, although sensitivity to some spin recoveries was corrected by fixing two longitudinal strakes to the rear fuselage just ahead of the tailplane. As a result, the fully aerobatic Chipmunk was ordered as the ab initio trainer for the RAF. De Havilland (UK)’s factories at Hatfield and Chester eventually built 735 Chipmunk T Mk 10s and its overseas variants for fourteen international air forces. The differences from the Canadian model were the regrettable loss of the bubble canopy (shaped like that of the Sabre fighter), a modified version of the Gipsy engine and the use of an all-metal Fairey-Reed propeller.

The first seven RAF Chipmunks were delivered to Oxford UAS on 3 February 1950. All seventeen UASs would eventually receive the aircraft to replace their DH Tiger Moths and North American Harvards. The Chipmunk made its first appearance on the public stage through an unusual display at the 1950 SBAC (Society of British Aerospace Companies) Airshow at Farnborough. The aircraft was flown by two RAF instructors, Flt Lts Everson and Hough, in which both a range of smooth aerobatics and a hair-raising display of ‘crazy flying’ by the supposed student were flown. This innovative demonstration of the Chipmunk’s flying characteristics led to many orders from overseas, including Portugal, Ireland and Denmark. In addition to equipping the UASs, the Chipmunk was selected as the elementary trainer for all National Service pilots and the then Reserve Flying Training Schools. Later it was the elementary trainer of choice for both the Army, at Middle Wallop, and the Royal Navy at Roeborough airfield near Plymouth. The Chipmunk also joined the elite ranks of the RAF College at Cranwell where it replaced the Percival Prentice in becoming the first aircraft that the cadets would fly. One Chipmunk, WP 912, became a temporary member of the Royal Flight, where it was used to teach HRH Prince Philip to fly; WP 912 now resides at the RAF Museum at Cosford.

The Chipmunk also had a couple of interesting ‘war roles’. The first was a brief time with the re-formed No 114 Squadron, operating in the airborne spotter role from Nicosia in Cyprus during the anti-EOKA operations of the late 1950s. The second was in the 1980s when two Chipmunks were based at RAF Gatow, in Berlin, to exercise the rights of UK military aircraft to overfly the Russian Zone of the city. The aircraft also gathered much intelligence in support of the then secret operations ‘NYLON’ and ‘SCHOONER’. From the 1950s onwards, the Chipmunk also became a popular civilian aircraft, being used for training, aerobatics and crop spraying. Most civilian aircraft were ex-military and many can still be found all over the world. There are two Chipmunks on the RAF books even today, one of which is a veteran of both Cyprus and Berlin: WG 486. These 60-year-old flying legends are with the RAF’s Battle of Britain Memorial Flight at RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire, where they give the flight’s volunteer pilots their first lessons in flying a ‘tail-dragger’.

I started flying the Chipmunk with Jack Hindle on Wednesday 14 June 1967. This would be my first flight for over six weeks. I had not previously experienced such a long time on the ground since I had started flying training over five years ago. It was also to be my first ever flight as a pilot in an aircraft with a piston engine, a propeller and a tailwheel. One immediate difference I noticed was that we did not wear an inflatable lifejacket (often referred to as a ‘Mae West’, in tribute to that rather well-built woman-shaped woman of the early cinema). Nor did we need to wear the funny straps that we used to put round our legs, called leg restraint garters, which helped to keep our legs from being damaged during ejection. At first I felt half naked without these encumbrances, but I soon got used to it and rather liked the feeling of freedom it gave me inside that tiny cockpit.

Looking around and getting aboard the Chipmunk was a whole new experience for me. It seemed very small and cramped after the Canberra. The wingspan was only 34ft, not much more than the span of the Canberra’s tailplane and, at 25ft, the length of the fuselage was barely the same as the chord of the Canberra’s wing! Once I had fired up the engine, whose starting system appeared to use 12-bore shotgun cartridges, I thought that the little machine would shake itself to bits before we got off the ground. It all seemed so crude and fragile.

Then, once the chocks were pulled away by the ground crew, who were well versed in avoiding that ‘whirling metal on the nose’, there was the complicated way of setting up the brakes to work differentially. I had to apply full rudder and pull the brake lever, which was like something from a 1930s motorcar, until I felt resistance. While doing this I had to lightly depress a collar around the top of the handle so that I could feel the small pall at the bottom of the lever clicking over a toothed ratchet. A couple of ‘clicks’ were then added, then the lever was released and that number of clicks was set from the off position. This meant that when I subsequently applied rudder I would get some differential brake to help me steer the little beast.

And steering accurately on the ground was vital, because with the aircraft sitting on its tail I couldn’t see ahead because the Gipsy Major engine was in the way. I have a very short back, which didn’t help either, even though I was using an extra cushion! So the first lesson was in weaving; not as in cloth, but as in moving the nose continuously from side-to-side, so that I could make sure that there was nothing in front of us that I might run into and chew up with the prop.

By the time we got to a position near the end of the runway I was getting a bit apprehensive. I wasn’t sure I could keep this diminutive but lively aeroplane straight on the runway. Even though the wind wasn’t strong I could feel its effect on us as we moved along the taxiway, and Jack had reminded me to keep the stick back to prevent the tail from coming up inadvertently. In my previous jet flying the wind had to be blowing a near gale before you really noticed its effect on the aircraft. But before take-off there was something else new. We had to run the engine up to check that both magnetos were working properly and that the oil pressure and temperature were acceptable for us to commit aviation. With jet engines, if they start – generally speaking – you can use them without further ado!

After carrying out this noisy procedure it was time to ask Air Traffic Control (ATC) for permission to take off, then line up on the runway and go. As I opened the throttle smoothly and progressively to full power I had to dance on the rudder bar to keep straight and then move the stick forward to lower the nose and get the wings to the correct angle to start producing lift. As the nose went down there was a definite directional lurch – so that’s what ‘gyroscopic moment’ does!6 Despite being subject to the pulling force of only 145 horses, it all seemed to happen very quickly and we were airborne. I accelerated (if that’s the right word) to 70kts and raised the nose to climb at that speed. In the Canberra the airspeed indicator had only just started to read at 70kts!

To say that the rate of climb was sedate would be an understatement; it was around 700ft per minute (fpm). I was used to at least 3,500fpm after take-off! It was noisy, there was constant vibration and the view wasn’t great. The cockpit canopy, which I had shut firmly before we took off, was close to my helmet in all directions so I felt that I could barely move my head sideways. The instrument panel, which was very uncomplicated, seemed very close. As I looked around I could see the wings sticking out (not that far) on each side and, with a great deal of effort, I could twist around and just make out the tail. It was then that I remembered that the fuel gauges were not in the cockpit with me, but outside on the top of the two fuel tanks in the root of each wing. I could only just make out what they were indicating! But, I told myself that, like all things unfamiliar and new, I would soon get used to it.

Once we had climbed to 6,000ft, which had taken about ten minutes, I was encouraged by Jack to get more of a feel for my ‘steed’. First of all we stalled the aircraft in straight and level flight with the flaps up and then down. The minimum stalling speed was about 40kts: ridiculous! Then Jack took control and said, ‘Follow me through.’ So I put my hands and feet lightly on the controls and he showed me how to get the Chipmunk into a spin. I hadn’t done this for over four years, so I was a bit apprehensive. After closing the throttle, the application of ‘full rudder’ and ‘full back stick’ made the little machine flip over on its back, drop its nose and start rotating at what felt like a very rapid rate. It was actually taking only a couple of seconds to do one rotation.

Just as I was starting to get dizzy, Jack applied the recovery drill and the Chipmunk stopped spinning as quickly as it had started. He then let me have a go. The tedious bit was climbing up again to a safe height to start all over again. We needed to have recovered at a minimum height of 3,000ft above ground level (agl). This reminded me again that there was no ejection seat, something I had not flown without since my Air Training Corps gliding days. If the aircraft did not recover by that height, we would have to open the canopy, undo our seat harnesses, stand up, hurl ourselves over the side and pull the ripcord of the parachutes that we were wearing. It was all so different! Like going back to the so-called halcyon days of aviation, but at least we didn’t have an open cockpit.

However, for the first time in well over three years I could easily, with very little physical effort, manoeuvre an aircraft in a really spirited manner. It was great to be doing this again! Having tried steep turns, which needed full power to retain a reasonable speed, I progressed back into the world of aerobatics.

A loop from a dive to gain about 130kts seemed to be over before it had started and only took up about 600ft of sky! Barrel rolls were similar, but when I tried a slow roll the engine very disconcertingly coughed and spluttered as we reached the inverted position. It did a similar thing as we cart-wheeled round the top of a stall turn. I also discovered that it was easier to complete that manoeuvre one way than the other, which, I was told, was all to do with the engine torque and propeller slipstream effects. After a few more manoeuvres Jack realised that I was enjoying myself far too much so he told me to close the throttle and glide to earth to make an approach to a suitable field, going around at not below 100ft. This exercise would become very familiar to me; it was called a Practice Forced Landing or PFL for short. And we were going to find a farmer’s field to land in!

If the engine had stopped in my Jet Provost or Vampire and I had not been able to make it to an airfield with a proper runway, the drill was to make an emergency call and then pull the black-and-yellow exit handle. Mr Martin Baker’s excellent seat would then get me out of the aircraft in seconds and I would catch up with events hanging on the parachute. The rest was up to gravity and luck.

During the descent for our Practice Forced Landing, I was taught that it was essential to open the throttle at regular intervals to ensure that the engine would respond properly when we needed it at the bottom. Apparently, prolonged time with the throttle closed might oil up the spark plugs and cause the engine to misfire badly or even stop. No wonder everyone was so pleased when Frank Whittle invented the jet engine!

During this part of the exercise I was taught how to tell where the wind was coming from and how to choose a suitable field. Then how to fly a spiral pattern in the sky to make sure that I would end up pointing both into the wind and into my chosen field at the same time. Once I’d got a basic handle on this we returned to Little Rissington for a few circuits and landings.

Jack demonstrated a normal, powered approach and landing to me first. Initially I thought that he was a long way out from the runway until he explained that we were going to land on the grass runway, which was halfway between us and tarmac one. Another new experience! We flew downwind at 90kts and did the pre-landing checks; these had a mnemonic that could be remembered easily by recalling the phrase ‘My Friend Fred Has Hairy Balls’!7 At the end of the downwind leg the speed was reduced to 70kts and the first of two stages of flap was selected using a large lever on the right-hand side of the cockpit.

The final approach was initially flown at 70kts, then full flap was selected, the speed reduced to 65kts and, when we were close to the ground, the throttle was pulled smoothly back as far as it would go. Then the idea was to fly level at a few inches above the ground until the nose reached what is known as the ‘3-point attitude’. This position of the nose above the horizon had to be learnt. At that stage one had to stop moving the stick back and, in theory at least, the little machine would flutter the last few inches smoothly to earth and touchdown with all three wheels at the same time. This was known as a ‘three point landing’ or ‘three-pointer’ and was a highly desirable outcome.

Well, the practice was very different. I tended to produce at least three landings from each approach, none of which were three-pointers! Jack was chuckling away in the back seat and giving occasional hints and tips. After what seemed to be an age of flying around the circuit, bouncing on the grass and spending a lot of time skittering sideways he said: ‘Right, lad, that’s enough of that. Let’s stop next time and go ’ave a coffee.’ None too soon for me, I mused. I was beginning to get despondent – would I ever get the hang of flying this funny little flying machine?

It turned out that what Jack had really meant was that we would stop next time and he would get out and ‘go ’ave a coffee’. As he dismounted he leaned over and said: ‘Just go and enjoy yourself for half an hour. I’ll see you later.’

I couldn’t believe his confidence! By the time he had climbed out of the back and his straps there had secured so that they wouldn’t interfere with the controls, I was seriously wondering if he had sound judgement. I had not really felt comfortable anywhere near the ground in the ‘Chippy’ and I just hoped that enough basic instinct would get me back safely. Half an hour wasn’t long, so I took-off and climbed up high enough to do some more of those delightful aerobatics and then returned to do a few circuits. The landings weren’t much better than before, but they weren’t any worse; so if they were good enough for Jack they were good enough for me. Actually from my third approach I actually touched down only once, so I decided that was sufficient and taxied back for my cup of coffee.

So that was the fourth aircraft type in my Log Book. Now all I had to do was learn to fly it well enough to have the spare capacity to talk to a student at the same time. But I wouldn’t start learning how to do that for another couple of weeks. Thankfully there were about another dozen flying hours to be devoted to honing up various skills and gaining an instrument rating (IR).

When the day came to do that, I had to fit the usual blind to my helmet visor; this was designed to stop me from looking outside while still allowing me to see the instruments. However, the cover that was used over the artificial horizon (AH) in the other trainers I had flown could not be used because we were sitting in different cockpits. So when it came to the part of the test when reference to the AH was verboten, known as ‘limited panel instrument flying’ and much trickier, then the AH had to be put out of action. This was relatively easy in the Chipmunk because its rather basic design meant that the slightest attempt at an aerobatic manoeuvre frightened the AH so much that it refused to work properly until one had flown straight and level for five minutes. So the ‘limited panel’ part of the trip was done towards the end of the sortie and was initiated by the examiner carrying out a loop or a barrel roll before handing the aircraft back in some ridiculous attitude. Then one had to recover back to straight and level flight using the remaining over-sensitive instruments, all of which had a variety of errors and lags. Instrument flying had never been my strong suit so I found trying to fly this flighty little bird accurately, without reference to the outside world, extremely challenging. But somehow I succeeded and gained a new IR, albeit coloured white again instead of the green one I had on the Canberra.8 However, I had the feeling that clouds and poor visibility would be things that would be seriously avoided in the Chipmunk.

We also did some night flying, but only about four hours in all; perhaps another thing to be avoided. I soon discovered why. The Chipmunk’s electrical system was very basic; something like a 1940s motor car: it had a single engine-driven dynamo and a 12-volt battery. The only things that used this meagre electrical power were the heater coil embedded in the airspeed measuring pitot-static probe on the left wing, the three red, green and white navigation lights, the radio and intercom and the taxi lamp, which was like a small car headlight let into the top of the left undercarriage leg. There was also a minimal set of internal cockpit lights, selectable and dimmable by a couple of rotating dimmer switches. When I first walked out in the gathering darkness I remembered that my last night flight was also my final flight in the Canberra B(I)8 on No 16 Squadron and that had been on 20 April. It was now 4 September.