Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

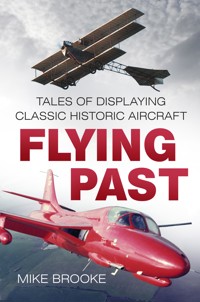

Following the four books describing his successful career as a military and civilian pilot, in Flying Past Mike Brooke gives the reader a fascinating insight into his experiences flying historic aircraft at airshows in the UK and Europe. From the highs to the lows he takes us through the feeling of flying a Spitfire, working with the Red Devils Parachute Team, flying with The Shuttleworth Collection and in the Harvard Formation Team, and the pressures put on display pilots – as well as the importance of preparation, discipline and safety. This entertaining and informative collection of stories will not only delight the many who have enjoyed Mike's series of memoirs so far, but also appeal to anyone with an interest in classic historic aircraft, aerobatics and airshows.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 370

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Mike Brooke

A Bucket of Sunshine: Life on a Cold War Canberra Squadron

Follow Me Through: The Ups and Downs of a RAF Flying Instructor

Trials and Errors: Experimental UK Test Flying in the 1970s

More Testing Times: Testing Flying in the 1980s and ’90s

In Memoriam

Pilots named in this book who died while flying historic aircraft:

Don Bullock

Neil Williams

Trevor Roche

Peter Treadaway

Euan English

Norman Lees

Mike Carlton

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mike Brooke, 2018

The right of Mike Brooke to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9038 7

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Aerobatics and Airshows

Part 1

The Beginnings

1

Aerobatic Training

2

Canberra Displays

3

The Red Devils

Part 2

Skywriting

4

Blackburn B-2

5

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

6

Harvard

Part 3

The Shuttleworth Collection

7

A Brief History

8

Multiple Moths

9

Bristol Boxkite and Avro Triplane

10

First World War

11

Trainers

12

Tourers

13

Oddities

14

Racers

15

Fighting Biplanes

16

Supermarine Spitfire

Part 4

Other Display Flying

17

The Harvard Team

18

Jet Heritage

Epilogue

Glossary

Acknowledgements

To write one book and get it published is quite a challenge. To write five is bordering on sadomasochism! Although many hours, days and weeks are spent in seclusion at the keyboard, with only memories for company, it is not a solitary task. I am blessed by having wonderful people on whom I can rely; people who are selflessly generous with their time in helping to make the finished product so much better for you, the reader.

At the top of the long list of those willing helpers is my best friend and wife, Linda. For the past seven years she has supported me tirelessly through the adventure of reliving my flying life, in the medium of words and pictures. She has proofread hundreds of thousands of words, corrected grammar, spelling and punctuation, and often improved many of my phrases and ideas. She is, and has always been, the wind beneath my wings. Thank you, my darling.

They say that a picture is worth a thousand words; and whoever ‘they’ are, they are right! Hence, I must give a special vote of thanks to Peter March and Steven Jefferson, two really talented aviation photographers. They have looked through their extensive collections and have allowed me to use their work to enhance this volume. I’m sure that you will agree that their photographs are a superb contribution to the end product.

An important part of writing non-fiction is to ensure that the facts are true and not fiction. Although I have my flying logbooks, various notes, articles and other written work that I have kept over the years, my recollection of some of the detail may not have been totally accurate. Therefore, I am very grateful to fellow Shuttleworth Collection pilots, Dodge Bailey and George Ellis, for checking that section of the book for ‘fake news’. I am also thankful that two books, given to me and signed by the author, the late David Ogilvy, provided valuable cross-checks on many elements. Also, I doff my hat to all those anonymous posters online who enable us twenty-first-century authors to discover things hitherto unknown; some of which actually prove useful!

Last, but by no means least, I am indebted to my publishers, The History Press, for offering me the opportunity, for the fifth time, to share my story. Especially I want to thank my editors, Amy Rigg and Alex Waite, who have continued to guide me and my book through the process of publication. I hope that you will agree that the final product is a credit to their colleagues at THP.

Mike BrookeRyde, Isle of Wight,April 2018

Introduction

Aerobatics and Airshows

Although some of you will be familiar with many aerobatic manoeuvres, I thought I would start with a description of a selection of the airborne gyrations that you may come across in the course of reading the tales that follow. Those of you that are familiar with aerobatics, usually known to the cognisant as ‘aeros’, as well as the airshow scene, might want to skip to Chapter 1.

Aeros

The following is not intended as an instruction manual on aerobatics. If you want to know more there are many books on the topic, as well as lots of stuff online. However, it will be hard to improve on the descriptions and instruction given in the late, great Neil Williams’ book Aerobatics, published by Airlife in 1975, with many reprints since. Neil was a test pilot and accomplished competitive aerobatic pilot, as well as being one of my predecessors at the Shuttleworth Collection. A measure of Neil’s amazing skill and awareness was demonstrated when he landed safely after a structural wing failure in a Zlin aircraft. The failure meant that Neil had to fly inverted to hold the broken wing in place and then roll upright just before landing. The poor old Zlin was a write-off but Neil was unhurt. By this amazing bit of flying he proved the saying that any landing that you can walk away from is a good one!

There are two basic types of manoeuvres that take the aircraft and its pilot beyond the norms of up-and-away flying: that is turns, climbs and descents. These are manoeuvres with a vertical component and those with a horizontal flight path; then there’s a third group with a combination of the two. A fundamental concept to grasp is that once aerobatics enter the flight envelope then the terms ‘up’ and ‘down’ can lose some of their meaning, especially as to where the nose of the aircraft is going in relation to the world outside and to the pilot. For instance, if I wish to fly upside down and maintain altitude then I have to push the nose ‘down’ in relation to myself, but ‘up’ in relation to the horizon I see out of the window. I will start by describing the purely vertical manoeuvres.

First, the loop. In the loop the aircraft is flown so as to describe a vertical circle in the sky; in fact the loop is usually not a perfect circle but a rounded ellipse. To do a successful loop sufficient initial speed and power is required for the aircraft to still be flying properly as it reaches the apex. If it doesn’t then it may stall and fall back, and not achieve the desired flight path. At the appropriate entry conditions the pilot must pull the stick back to achieve an acceleration towards the vertical. The G-force will vary with aircraft type and entry speed, but it should be sufficient to get the aircraft safely onto its back at the top of the loop. This G-force will reduce as the speed falls and then increase again on the way down. The aim should be to finish the loop at the same height and speed as the entry. To ensure that the loop is actually vertical the wings must be kept parallel to the horizon using lateral stick inputs and, especially on prop-driven aircraft, the slip ball must be monitored and kept central using the rudder pedals. A successful loop requires practice and application; if you have got it right you might well be rewarded by the satisfying bump of flying through your own slipstream as you approach the completion of the loop.

Next the stall turn: not all types of aircraft can perform this safely. The manoeuvre starts like a loop but once the aeroplane is in the vertical attitude, on the way up the pilot must stop the nose from pitching over any further and hold it there. That’s done by reference to the horizon viewed to the left and right; experience will play a part in knowing when the aircraft is travelling truly vertically. Then the pilot uses the stick to keep things steady. After a period of time, which will depend on the power-to-weight ratio of the aircraft, the speed will fall towards zero. At the latest possible stage, again learned by experience, full rudder is applied in the chosen direction. This will cause a rotation about the centre of the fuselage (yaw) and this must be continued until the aircraft is pointing vertically down. Aileron control may have to be used during this rotation to prevent the wings rolling out of the vertical. After stopping the yaw with rudder the pilot then holds the vertical descent until the right moment to pull the stick back and regain the height at which the manoeuvre was started. In prop-driven aeroplanes the slipstream from the propeller over the rudder will help the aircraft around the ‘turn’ at lower speeds than in jets. The stall turn is not usually performed in swept-wing, jet aircraft because of their strong dihedral effect, which makes the aircraft roll strongly when it is yawed. There is also much more chance of a spin developing if things go awry. There are variations that can be flown using the stall turn, such as the hesitation variant, where the yaw is carried out in four stages, using opposite rudder to achieve the hesitations in the yaw rate. Then there is the ‘noddy’ stall turn where the aircraft is fishtailed on the way up into the manoeuvre. More advanced versions include the Lomcovák, named after its Czech inventor, where a spin is initiated at the top and stopped when the nose is below the horizon again. There are even more adaptations involving negative rapid rolls and more prolonged descending rotations but those need not concern us mere mortals and are the preserve of that special breed of aerobatic aviators.

Moving on to the horizontal or rolling aerobatics: the first and easiest is the aileron roll. This is what it says on the tin: a 360-degree (or more) roll carried out using only the ailerons through the application of (usually) full lateral stick. Because the nose normally drops a little during the roll it is good practice to raise the nose above the horizon as viewed from the cockpit before the roll is started. High-performance jets can achieve eye-watering roll rates; for instance, the Folland Gnat trainer would roll at 420 degrees per second with full aileron applied at around 350kt. The lower the performance the lower the roll rate and the more the nose will drop. Much more eye-pleasing, but also much more difficult, is the slow roll. The aim of this is to fly a horizontal flight path while rolling the aircraft through 360 degrees at a rate of about 20–30 degrees per second, so taking around twelve to eighteen seconds to complete the roll. These figures are only a suggestion and are a good start point for training. The control inputs to complete a smooth, level slow roll without changing heading are complex to describe without using one’s hands and require repeated practice to learn. Suffice it to say here that all three control surfaces (elevator, aileron and rudder) need to be used to achieve the desired result. A slow roll will often end with the controls being crossed. However, once the technique is mastered then it will transfer to all aircraft types; it will just be the magnitude of the ever-changing inputs around the roll that may alter. By combining some of these control inputs at set points around a rapid aileron roll then four-point and eight-point hesitation rolls can be performed. In high-performance aeroplanes these can be impressive to watch.

Now the trainee aerobatic pilot can learn to blend rolls and loops to create even more manoeuvres. The first of these is the barrel roll. This manoeuvre, like the slow roll, is best experienced than described. However, it is essentially a loop carried out while rolling slowly. But, because of the roll, unlike the loop, it does not turn back on itself but progresses forward, while describing a graceful climb and descent. The name of the barrel roll helps one visualise its shape: imagine the aeroplane being flown round the inside of an old-fashioned wooden barrel. To fly it successfully requires just the right combination of pull, like a loop, and roll, like an aileron roll.

Another combination of the loop and roll is the roll-off-the-top. This manoeuvre is sometimes known as the Immelmann turn, named after its supposed inventor German First World War fighter pilot, Max Immelmann (21 September 1890–18 June 1916). He was credited with being the first pilot to achieve a kill using a synchronised machine gun and was the first German airman to be awarded the prestigious gallantry medal Pour le Mérite, also known as the Blue Max. To carry out this manoeuvre the first half of a loop is flown and then when the aircraft is inverted at the apex, the second half of a slow roll is flown so that the aircraft ends up flying in the opposite direction, level and at a higher altitude. Success depends on having sufficient energy at the top to carry out the roll safely. For those of a steelier outlook and flying aircraft with a good power to weight ratio, the roll-off-the-top can, if sufficient speed remains, be converted to a vertical eight. This is done by simply flying a second full loop all the way round to the horizontal and then making the first half of a slow roll followed by a half loop down to the original entry altitude. Speed control is an issue in this latter part of the manoeuvre and high G-levels may ensue. The finished product should look like its name: a figure eight vertically in the sky.

The figure eight can also be flown so that it lies on its side in the sky; this is known as the Cuban or horizontal eight. This manoeuvre starts from a looping entry but the loop is stopped after the apex is passed, with the aircraft inverted and the nose 30–45 degrees below the horizon. The wings are then rolled through 180 degrees and the dive continued to the initial entry height, when the manoeuvre is repeated – that will then achieve the figure eight with the aircraft back where it started. Half of this manoeuvre can be flown and is especially useful during air displays for turning around at the end of the display line – it is known as the half Cuban 8. If this figure is reversed, that is the aircraft is rolled on the way up and then the loop is completed from there, it is known as – guess what – the half reverse Cuban 8.

Airshows

There are many hundreds of airshows held annually around the world. These vary from huge international events (such as the trade shows held at Le Bourget near Paris, Farnborough near London, and in Dubai or Singapore), to the fly-in events on countless grass airfields in many nations. In 2015 there were 245 notified civil and military air displays in the UK. Again these varied in size and content from the Royal International Air Tattoo, with its eight-hour flying display, to the small, more intimate affairs held at flying club level. The usual UK statistic quoted by many in the business (and a big business it is too) is that annual attendance at airshows is second only to that at football matches.

The regulation of airshows has developed over the more than 100 years since those magnificent men first showed off their flying machines to an eager and inquisitive public. Initially the thrill consisted solely of seeing the fragile stick and string constructions simply take to the air and land safely again; one did not automatically lead to the other. That was probably another magnetic draw for the Edwardian crowds. However, very few aviators actually died in exhibiting their bravado and skill (or lack of it!).

The rules governing the application for an aerial event, its conduct and supervision have built themselves into voluminous tomes. These are usually written and amended by the national aviation regulatory authority; in the UK the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA); in the USA the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA); and so on. In parallel with these regulations, many country’s military authorities issue rules for airshows held at military locations, or for the participation of military aircraft in other public aerial events. Nowadays, the civil and military rules are usually well-harmonised. The aim of the whole shebang is to ensure that the aviation authority’s very basic remit is met; that is that nothing shall fall from the sky and hit anyone or do damage to property.

The supervision of each show is given to a nominated person, often known as the display director, and he or she will ensure that the rules are followed to the letter. Often a flying control committee (FCC) will be formed to help supervise and approve all the participants’ routines. FCC members are usually seasoned pilots with flying display experience. The display pilot has to know all the regulations pertaining to exactly where he can fly during his display and to what minimum heights and maximum speed he must adhere.

He will be required to submit his routine for prior approval and fly it for the FCC to view and, if appropriate, comment on before the airshow happens. All UK and US display pilots will have been observed by an approved experienced airshow pilot beforehand and given a display authorisation, which will denote any limitations on the pilot’s minimum altitude and whether or not he may fly in formation during a display. Another rule that is, these days, rigidly applied, certainly in the UK, is that non-operating crew cannot be flown in the aircraft during a public display; so no giving your best pal a seat during your show.

The onus for self-discipline, knowledge, experience and practice on display pilots is heavy. The pilot who wants to fly in an airshow has to know not only his aircraft’s handling, performance and limitations intimately, but also know his own limitations and stick to them in equal measure. Apart from peer pressure, there may be commercial or kudos factors that may drive pilots to try too hard. There’s also the weather, especially cloud and wind that can disrupt the practised pattern of the display. Another factor that crops up from time to time is just that – timing. Generally speaking, airshow timings slip to the right and often organisers will try to get back on schedule with short-notice requests to pilots to cut a bit out of their routine. I’ve also experienced the opposite when an item has dropped out and one is both urged to get airborne sooner and fly a ‘longer slot’. It’s easy to sit in isolation and say that you won’t do these things but with thousands of the paying public watching you feel a strong urge to help out. That’s when it can get dangerous!

Another thing to be aware of is that each event will have a ground plan that lays out the very important display line. This is usually a feature that is easily seen from above and must not be crossed so that the hurtling machinery is kept at the regulation safe distance from the crowd line. Other features on and around the venue may be marked for no over-flight below a certain height. Finally, the pilots will be given all the radio frequencies that they should use both before and during the airshow and any airspace restrictions that may affect them within the local area.

There have been hundreds of lives lost at public air displays over the past century or more, and each one of those has led to a tightening of the rules. The control and oversight of all those involved in airshows has become intense in recent years and I know that things have changed greatly in the almost twenty years since I last flew a public display flight. So some of what appears in my tales would no longer be allowed – but it was then!

The best pre-show final brief I know goes as follows:

‘Thrill the ignorant – impress the professionals – frighten no one.’

1

Aerobatic Training

I entered RAF flying training in May 1962; I was two weeks beyond my eighteenth birthday. I had already been a pilot for two years, but only of gliders and sailplanes. Now I was about to embark on a one-year course, during which I would fly more than 160 hours in the RAF’s first jet-powered basic trainer, the Hunting Percival Jet Provost; known variously as the ‘JP’ or the ‘Constant Thrust, Variable Noise Machine’! During that training course aerobatics would feature prominently alongside other required skills, such as night, instrument and formation flying (not, of course, at the same time!) and low- and high-level navigation. One of the offshoots of aerobatic instruction was learning the art of stringing several manoeuvres together and then, towards the end of the course, designing a sequence that could be flown in relation to a fixed point on the ground: the essentials of an air display. Those of us who showed enough aptitude at that part of the syllabus would participate in the end-of-course aerobatic competition.

Although this event would not be flown at low-level over the airfield, our efforts would be judged by an accompanying flying instructor, at a safe altitude over a prominent ground feature – often a disused airfield, with which early 1960s Britain was liberally littered.

Thinking caps were dusted off and we students were encouraged to bring together our aerobatic repertoires into a cohesive and flowing sequence, during which we had to adhere to a minimum altitude and maintain our position in relation to the nominated ground feature. Those of us who had been told that we would be taking part in the competition for the aerobatic prize would be allowed a couple of extra flying hours to practice, but no more.

Cometh the day, cometh the man. And that man was the figure of an instructor from another flight or one with whom one had never flown. The briefing would be concise and cover the mandatory minimum or base altitude, usually 5,000ft, and the location for the eight- to ten-minute sequence of manoeuvres. The student would furnish the instructor with a copy of his display sequence and the instructor would ensure that the student understood who was in charge.

‘Enjoy yourself, but don’t frighten me,’ was the nearest thing to encouragement that one could expect from the man in the other seat. He would spend the majority of the short sortie that followed in taciturn silence. Well, one hoped that he would! On landing, not much would be said as he had to confer with the other supervising instructors about which student pilot they thought most worthy of the prize. If not flown over the home base then the competition was judged solely from the air. I was fortunate enough to compete in such competitions at both basic and advanced training levels, as well as at the end of my instructor’s course. I never won – but came second, twice!

One initially challenging, but ultimately somewhat amusing, incident occurred during a practice session for the aerobatic competition at the end of my advanced flying training course. It was 1963 and we were flying the venerable de Havilland Vampire, one of the first British jet aircraft. The Vampire had been designed in the early 1940s and first flew in 1943. The version we flew at our flying training school was the two-seat trainer, known as the Vampire T.11, which had side-by-side ejection seats crammed into its rather small cockpit.

On the day in question, I had gone off on my own to fly my display routine and had made my way to a disused wartime airfield only five minutes’ flying time from our base at RAF Swinderby, near Newark. I set up for the first manoeuvre, which was an arrival at 420kt and the base altitude of 5,000ft at 90 degrees to my chosen display line, which was the main runway. I then pulled 5g into a vertical climb, during which my aim was to roll through 270 degrees and then carry out a loop along the display line. However, as the G came on there was a bit of a bang and I found my view out of the window disappeared. The seat pan had collapsed beneath me and the top of the Vampire’s rather long stick was now right in front of my face! I was still hurtling skyward and had no real idea which way was up! I decided to push the stick forward and keep full power on the engine until I could see what was going on. As the aircraft followed a nose-down trajectory I became weightless and I floated up in the cockpit with the seat still firmly attached to my bottom by its straps. Once I had found the horizon, I levelled off – and immediately disappeared back into the bowels of the cockpit!

I reached down to find the large lever that raised and lowered the seat – all the while flying as straight and level as I could by reference to the instruments, because I couldn’t see anything useful out of the window! I found the lever and tried to depress the plunger that released the locking mechanism, which normally allowed the pilot to set the seat pan at the right height. It wasn’t there! The lever could no longer be moved. The whole thing had jammed at its lowest position. As I was a pilot with a very short back length I usually had the seat set at its highest position; now I was stuck with an extremely limited view of the outside world, flying along at about 300kt.

Befitting its vintage and initial role as a fighter, the Vampire did not possess an autopilot or significant navigation aids. However, I knew that I wasn’t that far from base so I put out a radio call explaining my predicament and requesting a heading to steer to come home. Once I had received that crucial bit of information I turned the jet onto the required heading and flew along using the instruments, all the while wondering how I was going to land without being able to see the ground.

It wasn’t long before the air traffic controller told me to reduce altitude and call the local controller before joining the visual circuit. I did so.

‘Roger, Delta 36, report when you have the airfield in sight,’ he said. He obviously hadn’t thought things through.

I rolled the aircraft nearly inverted briefly and looked up to see if I could spot any recognisable local ground features. Sure enough, I spotted the edge of the airfield and turned left to carry out an orbit until I had worked out what to do.

‘Delta 36 is holding overhead at 1,500ft,’ I announced. ‘I can’t see out very well so I’m going to loosen my straps and see if I can get a bit higher in the cockpit.’

This initiated a response from the duty instructor. ‘Delta 36, put your ejection seat safety pins back in and then unstrap and try to move across into the other seat,’ he said. Either he was a tiny person or he’d forgotten just how little room there was in here! In these situations it was best not to argue, but rather give the impression that you would comply.

‘Roger,’ I said.

In the event I could not reach the holes at the top of the seat for one of the safety pins but I did replace the one at the bottom, between my legs. I then loosened off the straps and pushed upwards with my feet on the floor, this resulted in a bit of undulating flight while I locked myself in a semi-upright position. But now I could see out well enough to land.

‘Delta 36 is downwind to land,’ I announced, as confidently as I could muster.

‘Roger, 36, you are number one,’ came the reply.

I flew the well-practised pattern until I was pointing at the runway, flaps and wheels down and with a clearance to land. As I passed 300ft, at just the right speed, I was congratulating myself in overcoming the problem. Then it struck me that after landing I would need to use my set of presently out-of-reach rudder pedals to keep straight, or at least avoid swerving off the runway, while applying the brakes with the lever on the stick. So the last thirty seconds of concentration on a decent arrival were disturbed with working out what to do once I was down.

After the bump announcing contact with terra firma I let myself fall back into a sitting position with my feet going forward onto the rudder pedals and I started braking. As I could no longer see the runway in front of me I used the compass heading as a guide and craned upward to look over the side of the cockpit canopy, which was a bit lower than the windscreen ahead. That way I could see the edge of the runway and avoid any tendency to take a cross-country shortcut back to the dispersal area. It worked and I came to a walking pace about two-thirds of the way down the runway. The taxiway turn was, fortuitously, on my left so I kept going until I was clear of the runway, came to a stop, raised the flaps and got back on the radio.

‘Delta 36 – is clear and shutting down – please send a tractor to tow me in.’

But the funny things that happened to me weren’t over. The technical fault that caused the seat pan failure was just that. However, I returned to base with a self-inflicted fault on my next sortie.

This time I had got all the way through my aerobatic sequence successfully, three times, and was about to come home. But I had earlier watched one of our instructors practising his air display routine, which had finished with him flying inverted and extending the undercarriage prior to making an inverted turn onto final approach to land; he rolled upright once lined up with the runway. It looked good so I thought I’d try it before I went home; I wouldn’t get another chance.

Having rolled inverted and pushed on the stick to fly level, I checked that the speed was below the limit of 190kt and lowered the landing gear. That seemed to go well enough so I started an inverted left-hand turn. Of course, at 5,000ft I had nothing to line up with so I straightened up and, still flying upside down, I reached down to raise the undercarriage. I grasped the appropriate lever with my left hand and pulled. It wouldn’t budge. I tried a bit harder – still unmovable. Hey ho, I thought, leave it down and go home a bit slower than usual.

When I arrived at the ‘line hut’, where we signed the aircraft back over to the techies, I wrote the following in the aircraft’s RAF Form 700, its technical log: ‘While inverted I selected the undercarriage down (up) and after 30 seconds I tried to select it up (down) and the lever would not move. Returned with the u/c locked down.’

Some time later I was ordered back to the line hut for words with the SNCO in charge. I walked in and a small crowd of chaps was gathered with the redoubtable ‘Chiefy’, who was fixing me with a steely glare. I could tell that I was not at the top of his popularity list.

‘Ah, Mr Brooke. We took your kite into the hangar, jacked it up and plugged in the hydraulic rig and guess what, sir?’ (The latter syllable came with that degree of cutting cynicism that SNCOs reserve for very junior officers in the wrong!)

‘It worked?’ I ventured.

‘Yes – several times. Fault not found. Now then, do you know what stops anyone from retracting the undercarriage when the aircraft’s on the ground?’ The ‘young fellah, me lad’ was left unsaid.

‘Yes, chief; it’s the on-weight micro-switches,’ I replied, with a smile to abate his underlying impatience.

‘And what makes them work?’

‘The weight of the aeroplane squashes the undercarriage legs and closes the micro-switches,’ I replied, with a confident air.

‘And what is it that they activate to stop you raising the undercart?’ This was getting like the technical ground school exam all over again. And this time I either didn’t know or couldn’t remember. The result was the same.

‘I don’t know chief.’

‘Well, young sir, there’s a steel rod that slides across to stop you being able to raise the undercarriage lever. Simple, innit?’ The ‘just like you’ also remained unsaid.

‘So there you are, for reasons that I can’t fathom, you’re flying upside down and you push the undercart lever down. It works and the wheels go out into the fresh air. As you fly along, still upside down, the wheels, which weigh quite a bit, get pulled towards the aeroplane by gravity and close the micro-switches. So the rod slides into place and when you go to pull the lever to get the undercarriage back inside the aeroplane, it won’t budge. It’s doing exactly what it’s supposed to do because nobody ever thought that one day some little pilot officer would come along and do what you did. If you’d have put the kite the right way up and then retracted the undercarriage it would have worked as advertised and it would ’ave saved my boys from a couple of hours’ work.’

‘I see,’ I rejoined meekly. ‘Sorry.’ The ‘I won’t do it again’ remained unsaid.

I didn’t win the aerobatic trophy. Part of the reason was that I flew with a very large Canadian Air Force instructor, with us on an exchange posting. His arms and legs kept getting in the way of some of the more extreme movements I had to make with the control stick – that’s my excuse and I’m sticking to it!

Within a few weeks I moved on to learn to fly the Canberra bomber and I thought that my aerobatic display days were over; I was wrong! However, through the RAF’s excellent flying training system I had learnt many skills that would stay with me throughout the next forty years. Aerobatics and formation flying were just two that I would use in many future arenas.

2

Canberra Displays

Those of you who have read my first book, A Bucket of Sunshine, may recall that, in 1966, my navigator Geoff Trott and I were selected as the RAF Germany Canberra display crew. We were then in the middle of a three-year tour of duty with No. 16 Squadron, based at RAF Laarbruch in West Germany. We were flying the B(I)8 version of the English Electric Canberra jet bomber and the squadron had two roles. The primary one was the low-level, day and night delivery of tactical nuclear weapons on targets in Eastern Europe. The bomb (the eponymous ‘Bucket of Sunshine‘) was carried in a bay underneath the aircraft that had hydraulically operated doors. We were part of NATO’s potential response to any incursion across the Inner German Border (IGB) by Warsaw Pact or nuclear forces. In effect, that made us also part of the international nuclear deterrent. Our other role, which was not a NATO role but a national one, was that of conventional, low-level ground-attack; again we had to be proficient by day and night. For this mission the aircraft was fitted with four 20mm cannon in a gun pack, fitted in the bomb bay, and could also carry up to six 1,000lb HE bombs, as well as flares for night attack. Unlike in the nuclear role, for this work we usually flew around in formations of two or four and, very occasionally, eight aircraft.

The twin-jet Canberra was first designed in the 1940s to fulfil the role of a high-altitude, high-speed (for its day) bomber. It could fly as high as 50,000ft. It was developed during the 1950s through several versions, ending with the PR.9 photographic reconnaissance version that saw service into the 1990s. The B(I)8 version was the same size as the original bomber, with a fuselage length of 69ft and a similar wingspan. The engines had a thrust of 7,500lb and the aircraft could weigh up to 50,000lb with a full load of weapons and fuel. The Canberra’s conventional flying controls were manually operated, no hydraulic assistance was provided, and its maximum allowed airspeed was 450kt.

On the squadron we flew mostly at very low altitudes, normally at 250ft above the ground by day or 600ft at night. If we had to go any great distance, like flying to the Mediterranean air bases that the RAF operated in those days, we normally transited at between 40,000 and 45,000ft and cruised at 0.74 Mach (74 per cent of the speed of sound). The Canberra was a simple and rugged aeroplane that could be demanding and tiring to fly during high-speed manoeuvring. It was especially difficult if an engine failed, especially at low airspeeds. Many aircrew had been killed following engine failures and we practised this emergency, especially on the T.4 trainer version; at Laarbruch we had access to two of these.

For an aircraft that was about as long as a Lancaster bomber and weighed around 20 tonnes, the Canberra was surprisingly agile. We did not practise aerobatics as such, but our initial nuclear delivery mode, with the acronym LABS (from the installed Low Altitude Bombing System) finished with a roll-off-the-top manoeuvre. This was started from 250ft and 430kt with a 3.4g pull-up in the vertical. At a pre-calculated angle (usually about 65 degrees) the bomb would be automatically released and fly a parabolic path towards the target, reaching a height of about 10,000ft before descending. It was equipped with a small radar altimeter that would make the bomb explode at about 1,500ft above the target; this made our bomb an ‘air-burst’ nuclear weapon.

During our ground-attack gun and bomb attack patterns we often flew wingover manoeuvres, during which bank angles beyond the vertical were achieved. These also gave us the opportunity to explore the relationships between speed and available turning performance and discover where the boundaries of the stall were.

When my squadron commander, aka ‘The Boss’, Wing Commander ‘Trog’ Bennett, called me into his office one day in spring 1966 I was quite taken aback at what he proposed.

‘Noddy (my nickname at the time), I want you to design a flying display routine of about ten minutes duration.’

‘Really, sir?’ I responded excitedly. ‘Who’s going to fly it?’ I really wasn’t expecting a Junior Joe like me to be let loose in front of the public.

‘You are, you chump. If I approve it I’ll send it up the line to the station commander and he’ll pass it up to HQ. Get cracking!’ So off I went to put some pretty lines on paper and think deeply about how best to show off our bomber to the public.

I drew on my RAF training and considered the aircraft’s limitations and how I could blend the variations of speed and manoeuvre into something flowing, and perhaps a little bit impressive or even exciting. I decided that I would submit two sequences: one for an overhead arrival at the airshow venue and another that commenced from take-off and went straight into a display. The latter would be more difficult, as I would be starting with no initial energy, whereas arriving at 450kt would not only be an impressive entrance, but give me lots of options. The arrival routine would be from the rear of the crowd at whatever minimum height I would be permitted. In those days arriving from behind the crowd was not only allowed, but was a popular option. Today it is totally verboten!

The two sequences were written down, sent up the line and came back in due course with an approval to start practices. This meant that I would practise the arrival option first, starting at a minimum altitude of 3,000ft above ground level over the airfield. In fact, I practised single elements of the routine before that, away from the airfield in free airspace and away from built-up areas. When I was confident that I could start stringing the elements together, and think about positioning, I received authorisation to practise overhead Laarbruch, usually late in the day. As my confidence and ability increased I started to reduce the minimum heights. The aim was to fly the sequence well enough to present it to the Boss and the station commander so that they could recommend to the Commander-in-Chief RAF Germany that I was fit to be let loose on the great European public.

Our display sequence started from behind the crowd rear at a speed of 450kt. As I passed over the crowd, I throttled the engines back and opened the bomb doors; the ensuing large ‘hole’ under the fuselage resulted in a booming noise, a very large version of blowing across the top of an empty bottle. It was a great attention getter. After crossing the display line, now doing about 330kt, I started a hard turn to the left and kept the bomb doors open. When we came round to abeam the crowd on the display line, hopefully at crowd centre, they would see the underside of the Canberra at a bank angle of about 60 degrees; the big wing would look quite impressive. I continued the turn, reducing speed, closed the bomb doors and, when the speed was below 190kt, lowered the landing gear. I needed more power to hold the speed at about 150kt so that I could lower the flaps. Now my flying technique had to be delicate as the steep bank angle could induce a stall if I let the speed drop any further. I also had to think about an engine failure and have enough control in hand to recover; especially should the engine on the lower wing fail. A way of doing that was to allow the aircraft to climb a bit on the far side of the turn; this would not be that obvious to the crowd as the perspective from their viewpoint would mask it.

At the completion of this final, quite tight turn I would raise the flaps and undercarriage as I rolled out, aiming about 30 degrees off the display line away from the crowd, holding the jet level, applying full power, accelerating and then climbing steeply to a point just beyond the end of the display line. The aim was to gain height to about 1,500ft and perform a steep wingover back onto the display line, descending back to my minimum height of 200ft and accelerating to be at about 350kt at crowd centre. In my original plan this would have been the initiation point for a steep upward roll, but this had been taken out of the routine by the worthies at HQ RAF Germany. So my modified routine was to initiate an offset loop, which is a steep turn flown at an angle of about 60 degrees to the horizontal. The height at the far side was about 3,000ft – but I could adjust that for cloud if necessary.