Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Mike Brooke's successful RAF career had taken him from Cold War Canberra pilot to flying instructor at the Central Flying School in the 1970s. For his next step he undertook the demanding training regime at the UK's Empire Test Pilots' School. His goal: to become a fully qualified experimental test pilot. Trials and Errors follows his personal journey during five years of experimental test flying, during which he flew a wide variety of aircraft for research and development trials. Mike then returned to ETPS to teach pilots from all over the world to become test pilots. In this, the sequel to his successful debut book A Bucket of Sunshine and its follow-up Follow Me Through, he continues to use his personal experiences to reveal insights into trials of the times, successes and failures. Trials and Errors will prove fascinating reading for any aviation enthusiast.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 640

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A DEDICATION

To the memory of Group Captain John W. Thorpe AFC, FRAeS, RAF

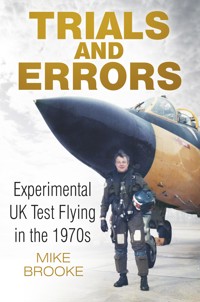

John Thorpe and I pose before my final jet flight as a pilot in an ETPS Alpha Jet in March 2004. This was also our last flight together. John is the tall one! (OGL (QinetiQ))

This book is dedicated to my good friend and fellow test pilot John Thorpe, aka JT. Although we both joined the RAF, as trainee pilots, straight from grammar schools and learnt to fly at the same Flying Training School, John was a couple of years behind me on that particular journey. It was the only time that he was behind me in anything – from then on he would always be out front. However, I did not meet John until June 1973 when we travelled together from our neighbouring RAF stations in the English Midlands to Boscombe Down in Wiltshire. There we would undergo two days of rigorous examination to see whether we were fit to be selected as student test pilots with the Empire Test Pilots’ School (ETPS). He was at that time flying the Harrier and had been on the very first Harrier squadron. We made that journey more in hope than in expectation.

Indeed, after the two days of challenging academic tests, demanding interviews and nervous waiting we departed together with even less hope and no expectation. As we drove up the hill away from Boscombe, John put our thoughts into words:

‘Well, I don’t know about you but I don’t expect to be seeing that place again.’

It was therefore with an element of shock and much surprise that we were both selected to attend the course; in the event, circumstances prevented me from joining the 1974 course, on which John was awarded the prize for Best Pilot; an indication of his outstanding mastery of the art of aviation. I attended the course the following year and John was by then a test pilot on A Squadron testing fighters and trainers. John was one of the two RAF test pilots who carried out the official Preview Assessment of the BAe Hawk trainer.

I next came across him when I joined the ETPS staff in early 1981. John helped me enormously to adjust to this new job and made sure that I was fully comfortable with everything before students were allocated to me. Throughout our time together on ETPS I never experienced anything but kind concern, calm control, good humour and exemplary and consistent professional standards from John.

Our paths crossed again, once more at Boscombe Down, in the late 1980s when he was now the CO of A Squadron and those extraordinary personal qualities came to the fore. He was an excellent leader and always set the highest standard for all in his unit, while maintaining an approachable and friendly demeanour.

John continued to serve at Boscombe Down, as Chief Test Pilot, Director of Flying and, latterly, as a civilian test flying tutor on ETPS. He ended up serving at Boscombe Down for a total of nearly twenty years; which made his remark to me in the summer of 1973 all the more ironic!

John Thorpe died, after fighting cancer, in December 2013 in Calgary, Canada, where he had made his home with his wife Jenny. He was, as they used to say in the Harrier force, a bona mate, one of the best I have known. I shall miss him.

I would also like to remember two of my friends and colleagues who lost their lives during flight test activities. The first is Flt Lt Sean Sparks, RAF, with whom I worked at Farnborough and at ETPS. Sean died when the Jaguar in which he was flying crashed into the sea off North Devon after suffering a catastrophic birdstrike. The second is Lt Cdr Keith Crawford, USN, who was a fellow tutor of mine at ETPS. Keith died while testing a McDonnell F-18 Hornet from the US Naval Flight Test Facility at Patuxent River, Maryland. Both these men were good, reliable and true friends who loved their flying.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Once more I have been unstintingly supported throughout this project by my wife, Linda. She has put up with me spending many hours with my nose in my flying logbooks, typing one-fingered, and then she proof-read every page. She has corrected and advised even more thoroughly than she did during the production of my two previous books. I cannot thank her enough. However, if you do spot any errors please don’t blame her; the ‘book’ stops here – with me!

I also want to thank the staff of The History Press for keeping me on their ‘books’ and doing such a good job of producing this volume. Thanks also go to several people who have helped, provided pictures and advice and helped me to produce something that would not have been as good without their input: John Bradley, Norman Roberson, Allan Wood, Norman Parker, Jenny Thorpe, Natasha King and the folks of the Photographic Division at QinetiQ Boscombe Down. Last, but by no means least, I want to thank Matt Savage of Mach One Manuals (www.mach-one-manuals.net) for providing the cockpit illustrations.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction: What is a Test Pilot?

Prologue

Part 1: Learning to Test

1 Getting Ahead of the Game

2 And So to School

3 A Plethora of Planes

4 So Much to Learn

5 Out of Control

6 The Lighter Side

7 Travelling Light

8 Rocking and Rolling

9 Beavering About

10 A-Buccaneering We Will Go, Me Lads!

11 Graduation at Last

Part 2: Testing to Learn

12 Farnborough

13 Settling In and Dropping Fish

14 Dropping Bombs

15 Not Only Owls Fly Low at Night

16 Varsities

17 White Hot Technology

18 Playing With the Navy

19 And the Army

20 Other Hotspots

21 Over the Pond

22 Becoming a ‘Truckie’

23 A Miscellany of Work and Play

Part 3: Researching Radar

24 Into the Black

25 A Unique Flying Machine

26 Whirlybirds Are Go!

27 Variety is the Spice of Life

28 Fiasco

29 Moving on Again

Part 4: Back To School

30 Back on the Learning Curve

31 Tutoring and Other Flying Stories

32 American Visits – USAFTPS

33 American Visits – USNTPS

34 European Tours

35 Operation Corporate

36 Anniversary

37 Choosing a New Path

Appendix A: A Brief Lesson in Aerodynamics

Apendix B: Cockpit Illustrations

Copyright

INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS A TEST PILOT?

To design a flying machine is nothing. To build it is not much.

But to test it is everything.

(Otto Lilienthal, Pioneer aviator, 1848–96)

From the very early days of flying someone has had to make the first flight of a new flying machine. Usually, in that now far off era of ‘stick, string and cloth’ flying machines, it was the designer. Crashes were common but not always fatal, so giving those pioneers the chance to change things and try again. Eventually, as men became more expert at aviating, pilots would team up with designers to do the dangerous bit on their behalf, usually for some sort of remuneration. And so the role and profession of the test pilot developed.

As the aviation industry matured and aircraft companies proliferated, bold aviators, often men with a military background, were recruited to fill the posts of company test pilots. Many became famous in their, sometimes short, lifetimes. There were also skilled pilots in the armed forces who were selected to fly experimental aircraft and carry out research and development flights at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) and the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE), but the role of the test pilot was not formalised or standardised across the industry or within the services. However, events during the Second World War brought an end to the DIY approach to test flying.

On the day that the war was officially announced by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, 3 September 1939, the A&AEE upped sticks from its vulnerable east coast location of Martlesham Heath, near Ipswich, and moved west to the safer, more distant environs of Boscombe Down, on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. In 1942 the man in charge of clearing aircraft for service use, known as the Controller Aircraft, Air Marshal Sir Ralph Sorley, made a decision. He wrote to his fellow 1920s test pilot, Air Commodore D’Arcy Greig, then Commandant of A&AEE, ordering him to form a school to train pilots to become effective test pilots. So the world’s first such training establishment, the Empire Test Pilots’ School (ETPS), was founded, with the first course starting in April 1943. On that course were a mixture of civilian and military pilots.

With the advent of the post-war jet era the image of the test pilot, always known in the trade as the ‘tp’, became crystallised in the public mind as a dashing character who drove a sports car, flew his jet in a business suit and almost always wore a bow tie. People soon thought that these cool and daring men flew their brand new jets with bravado and a white silk scarf to hand. That image has not really gone away. ‘How exciting!’ is often the response to the announcement that one is a test pilot.

Well, sometimes it is, but not as often as folk would like to think. The description of ‘hours of tedium punctuated by brief periods of terror’ could be nearer the truth! These days the military test pilot, which is the remit of this book, never gets to fly the first flight of a brand new aeroplane or helicopter; that is the privilege of the company tp. However, during his career he may well fly many ‘first flights’ of new systems, weapons and equipment; however, much of the most futuristic research is done in very old and trusted aircraft. Therein lies the definition of another sort of tp – the experimental test pilot.

There are also military test pilots whose work is concerned with the release of an aircraft to the customer – that is the branch of the armed forces that is going to use it. He has to be concerned with its safety and effectiveness for the role for which it was designed. Things have changed in the way that military test pilots work since I was last involved in the business, which is now over 20 years ago. The scale has reduced markedly and collocation, rationalisation and privatisation have all changed the face of military aircraft and systems procurement and assessment.

But the basics of test flying should not have changed. Far from dashing into the air on a solo mission to ‘push the envelope’ the underlying principle is still a progressive approach, following an in-depth assessment of the potential risks and designing the optimum protocol. That way there should be no surprises; I was once told that the last thing a test pilot should be is surprised! Take it step-by-step and review before moving on. And most of all – BE OBJECTIVE. That means that any problem that turns up, especially in the areas of handling and stability, should be analysed carefully and not blamed on the pilot. That’s one of the reasons why service pilots often have disdain for a tp’s findings about their own ‘wonderjet’.

However, the job of the military test pilot is, or should still be, both challenging and rewarding. I found it so – read on and judge for yourself!

Whereas my story thus far, contained in the books A Bucket of Sunshine and Follow Me Through, has included some basic technicalities about flying, this tome will, by its very nature, delve a little deeper into the science attached to the art of aviation. So I have included, at Appendix A, some hopefully simple explanations of some of the technical terms this book contains. I know that for many readers, who have followed a similar path into test flying, this appendix could serve at best only as a refresher, if it serves any purpose at all!

But there may be some, indeed I hope that there are many, readers who do not have a deep understanding of aerodynamics and the principles of flight necessary to follow fully all my tales. So to those folk I commend that if you get stuck on a word, phrase or symbol that really obstructs your reading do not hesitate to turn to Appendix A – ‘A Brief Lesson in Aerodynamics’.

PROLOGUE

When I was a lad in Yorkshire I was incessantly interested in things that flew. I watched birds. I watched aeroplanes. I went to air shows and often spent hours at the local aerodrome, now Leeds Bradford Airport, just taking in the exciting atmosphere of post-war aviation. There were the diminutive private aircraft as well as the DC-3s of the BKS airline company and a whole collection of flying visitors. An RAF Auxiliary Air Force squadron of Meteor fighters was also based there. To see them making formation take-offs and zooming off into the Yorkshire skies was the height of excitement for a 10-year-old. During those long summer days I used to put up my parachute-panel wigwam in the back garden, get a rug and lay out on the lawn with my dad’s best binoculars, an exercise book and a pencil to hand. Then every time anything flew within earshot or eyeshot I would record what it was, at what height I thought it was at and in what direction it was flying. Mostly these identified flying objects were DC-3s!

My favourite Christmas and birthday presents were book tokens. Grasping them in my small sweaty hands I would then catch the bus into Bradford, walk up to a bookshop near the entrance to Kirkgate Market and buy the Observer’s Book of Aircraft for that year. When I had got that I would look for any other books about flying that I could afford. Otherwise I would scour the local library for similar literary content. Books about test pilots were particularly favoured; what excitement they contained. I wondered dreamily if one day I too could be a test pilot. Of course, I was naïve and in the full flush of that limitless, youthful expectation of what life could bring. Then every year, on one day in September, I would be glued to the small black and white TV in our living room for the two-hour broadcast of the Farnborough Air Show, with Charles Gardener’s wonderful commentaries: ‘… and over the Black Sheds comes ‘Bee’ Beamont in the Canberra’ or ‘from the Laffan’s Plain end here comes Neville Duke in the Hawker Hunter. You can’t hear him yet, but you will!’ And as Roly Faulk flew past in the Avro Vulcan, ‘Goodness me! He’s going to roll it!’ What I would have given to go there and see it all live.

At the age of 11 I discovered the local Air Scouts, then later the Air Training Corps, so it was no surprise to anyone, my parents included, when I joined the RAF in 1962. I became a pilot and I flew the Canberra in Germany in the low-level nuclear strike and tactical interdictor roles. When that was over I became a flying instructor, first on the de Havilland Chipmunk and then on the Canberra again. But, in the mid 1970s, in order to achieve an ambition I had secretly held since my youth, I had applied for, and been accepted into, the ETPS. I also thought that it might break the cycle of flying old aeroplanes!

So, thirteen years after taking the Queen’s shilling1 I was on the threshold of a new career. All that childish reverie of slipping the surly bonds of earth in a shiny, brand-new flying machine to climb aloft and touch the face of God was, perhaps, going to become a reality! Here I was, 30 years old and with 3,200 hours in my logbook, about to become a member of No. 34 Fixed Wing Test Pilots’ course at ETPS at Boscombe Down, in Wiltshire. Maybe my dreams could come true?

Note

1 Meaning to sign-on in Her Majesty’s Armed Forces.

PART ONE

LEARNING TO TEST

1GETTING AHEAD OF THE GAME

So here I was on another threshold – the door to the ETPS Ground School. It was a cold January day at the beginning of 1975 and I had walked the mile or so down from my married quarter on the top of the hill on which Boscombe Down airfield is spread, like a concrete and grass tablecloth. I was chilled, not just from the weather but also from apprehension of what was to come. In the summers of 1973 and 1974 I had undergone the rigorous examination of the two-day selection procedure to get here not once, but twice. I had been successfully selected the first time but illness prevented me from attending the 1974 course.1 But, because the selection procedure was competitive, I had to do it all again in the summer of that year. Thankfully I was reselected, but with one proviso: due to my relatively basic level of mathematics I needed extra tuition before the course started in early February. Because I had joined the RAF at the minimum age of 17½, I had left school after just one year in the sixth form. I had, therefore, only an O Level GCE in maths, although I had subsequently completed one year of instruction in calculus.

My results in the selection board maths paper had reflected my lack of depth in this area. So here I was, ready to receive special attention from the teachers of such mysteries as polynomial equations, differentiation and integration. I was not totally alone as a couple of other guys with a similar background and lack of achievement in sums were here for the same treatment.

We were soon directed to the classroom. I noticed that there was a great view out to the north, over Salisbury Plain, beyond the busy major trunk route to the southwest, the A303. I wondered how often I would be looking at that view over the following year. But there was no time for that now. A shortish, balding man in a white coat entered and stood on the slightly raised ‘stage’ in front of a huge roller-style chalkboard. He had the air of a hospital consultant confronted with a small group of patients who were not going to understand a word of his diagnosis and treatment. He was actually Wing Commander John Rodgers, the Chief Ground Instructor (CGI). He started the morning in the way he meant to go on, taking no prisoners and rolling the blackboard at a frantic rate, while writing all sorts of barely comprehensible symbols and numbers in rapid succession.

Later we would come to know, and sort of love, him as ‘Chalky’ and become well accustomed to his many catch phrases, such as ‘I’ve done nothing wrong’, usually to the accompaniment of erasing something from each side of an equation. There was also his uncanny knack of asking the only person who had not followed what he was doing to explain how he had arrived at some esoteric conclusion. Too often that would turn out to be me.

We did not spend all day and every day in the classroom. That would have been too much for our tiny minds. There were other things to sort out up at the ETPS Fixed Wing Flying HQ, which was situated in offices along the front of one of the hangars. The windows there overlooked the countless acres of the concrete parking area used by the many and varied types of aircraft at Boscombe Down. We had to be issued with flying kit, including bright orange flying suits, anti-G trousers, helmets, lightweight headsets for flying the transport types and an assortment of connectors and other bits and pieces, the purpose of which would eventually become clear. The very affable man in charge of our flying clothing, including anti-G suits, was most appropriately called Tony Gee. His small empire’s HQ was located in a wooden hut in front of the second set of hangars. Like all the ground support personnel Tony was a civil servant; however, the majority of the ETPS staff were service personnel.

The Officer Commanding (OC) was a group captain, with a wing commander Chief Test Flying Instructor (CTFI) and four fixed-wing tutors, three RAF squadron leaders and one US Navy lieutenant commander on an exchange appointment. There was also a Qualified Flying Instructor and Instrument Rating Examiner (QFI/IRE), who was there to help with conversions to type for everyone and keep the flying standards up to snuff. The Adjutant was Sgt John Hatschek and the Ops Clerk was LAC Bill Anderson, known ironically as ‘Flash’; because the only time he moved faster than a slow trot was when he drove the CO’s staff car! The Operations Officer, who helped to ensure that the daily programme ran as planned, was a civil servant called Ted Steer, who could be relied upon to point us in the right direction! There were also three air engineers who helped with the running of the school’s Armstrong Whitworth Argosy C1 turboprop transport aircraft and many other ancillary tasks within the school. They were Flt Lts Len Moren, who could often be spotted wearing carpet slippers, Terry Colgan, also the school’s entertainment officer, and Terry Jones, who, like us, had just arrived. On the other side of the airfield was the rotary-wing element, manned by RAF and RN (Royal Navy) tutors, plus a Qualified Helicopter Instructor (QHI).

To be ready to fly the diverse fleet of ETPS flying machines we were to be issued with a barrow load of Pilots’ Notes and checklists, known as Flight Reference Cards (FRCs). There were also a handful of small, neatly typed cards that gave the essential information on flying each of the half dozen aircraft types. All these documents had to be digested rapidly, but thoroughly, before each conversion flight. Unlike the normal RAF practice of taking several months to be taught how to fly a particular aircraft type, we would only be given a maximum of two flights under instruction before we were going to be allowed off the ground as captains of these aeroplanes. The ETPS fixed-wing fleet of the day was:

• Beagle Basset – two examples; one the standard, twin-prop, piston-engined, 5-seat light communications model and the other a specially modified version to demonstrate in flight the effects of changing parameters of aircraft design and aerodynamics. This one was known as the Variable Stability System or VSS Basset.

• Jet Provost T5 trainer.

• Canberra T4 and B2 twin-jet bomber and trainer.

• Hawker Hunter T7 and F6A fighter and trainer.

• Argosy C1 four turboprop transport and air-drop aircraft.

• Lightning T4 twin-jet, supersonic trainer.

The Ground School was challenging enough, but when I took the assorted volumes of aircraft knowledge home and thought about how much there was to learn in such a short time I began to wonder what I was doing here! However, that anxiety was offset by the frisson of excitement at the thought of being, eventually, let loose on such a wide range of aircraft. And it wasn’t long before that started. I was at the hangar offices of the school one morning, my head reeling from the latest mathematical revelations from Chalky. While I was enjoying a restful coffee one of the tutors, Sqn Ldr Duncan Cooke, a South African-born, ex-Harrier pilot, walked in. He had a brisk way about him and, with a friendly smile, he said, ‘I think that it’s time that you had a break, young fellah me lad. How’s about you and me flying the Hunter together this afternoon?’ My immediate response was a big grin. ‘I’ll take that as a “yes” then. Get your flying kit sorted, read what you can of the Pilots’ Notes and I’ll see you in the Ops Room after lunch.’

It was 16 January, thirteen years to the day since I had joined the RAF and still more than two weeks before the course would start, and here I was getting ahead of the flying game as well as the academic one. This was more than all right by me. The flight in the Hunter was going to be pretty intense, very little of the usual demonstration followed by practice and correction. There wasn’t time for all the correct Central Flying School (CFS) instructional procedure that I had come to know so well over the past eight years. This was the start of test pilot training, so finding out for oneself was at the top of the agenda!

I had flown in the two-seat, dual-controlled version of the Hawker Hunter on three previous occasions: twice during a visit to the Royal Navy’s Fleet Requirements and Direction Unit at RN Air Station Yeovilton and once when I visited the RAE at Farnborough. I had gone there before I attended the ETPS Selection Boards to find out what the test pilots at Farnborough did to earn their crust. One of them was Flt Lt John Sadler, an old mate who had been on No. 16 Squadron at RAF Laarbruch in Germany with me. When I had flown the Hunter T7 with John we had climbed out over the English Channel so that we could make a dive and go supersonic without annoying people with our sonic boom. That was the first time I had seen a Machmeter exceed one; admittedly by not very much! During those three trips the pilots had let me fly the aircraft for some of the time.

Now I was walking round the very attractive aeroplane that was one of Sir Sydney Camm’s aesthetic creations, being shown what to check before getting on board. Once that had been achieved I strapped into the left-hand seat and then looked around. It all seemed somewhat familiar because the seat procedures and the cockpit layout reminded me of the Canberra T4 trainer in which I had spent so many hours in the last three years. The view of the outside world was a little better, but not much, especially when the cockpit canopy had been lowered and locked into position. The Canberra familiarity continued when starting the engine. Essentially it was the same R-R Avon engine that I had used in the Canberra B(I)8 and was started by the identical cartridge system. All the flight and engine instruments were about the same; the only difference was that the aircraft was controlled from a single central stick, and not a yoke, and there was only one throttle.

By the time we had reached the holding point of Boscombe’s south-westerly runway, I had got used to using the handgrip brake and rudder to turn the aircraft. After carrying out the pre-take-off checks we lined up for departure. One new principle was that I didn’t need to learn the checklist sequences, in fact it was positively discouraged. Because we students would be flying a multitude of very dissimilar types, often three on the same day, then the FRCs were the only way that we could be sure that we had done everything correctly.

Another new approach was that there would be very little demonstration of techniques. Accordingly, I lined up the Hunter on the runway and Duncan just monitored things as I did the take-off. The acceleration was much like a Canberra: positive but not startling. At the briefed speed I moved the stick back, quite a long way it felt, and I was a little taken aback that nothing happened. Soon, though, the nose wheel started to lift off the ground. I held the slight nose-up attitude and at about 150kt we were airborne. Then I squeezed the brake lever and raised the undercarriage. At this point a gentle side-to-side wing rocking started, which I couldn’t seem to stop. In fact my attempts at correction were making it worse so I just held the stick central while the landing gear retracted. Once it was up I raised the flap.

The wing rocking had stopped and it was now very easy to hold the aeroplane still and let it accelerate to the climbing speed of 350kt. The wing rocking after take-off was all down to the relationship between the higher breakout force to initiate movement of the ailerons and the very low friction once the stick was moving. Like all Hunter pilots before me, I would see for myself that pilot compensation was the cure and after a couple of sorties I knew what to expect and how to avoid it instinctively. It was my first lesson that no aeroplane ever built is absolutely perfect in every respect.

The flight itself was an exploration of the Hunter’s flight envelope, although we didn’t go supersonic. We stalled, with the wheels up and down, the flaps up, part down and fully down. At best the stalling speed was about 110kt. Then a few aerobatics, looping from 400kt, rolling at 350kt and all the while the control forces were very light. Hard turns revealed that the maximum rate of turn at about 360kt was found as the airflow started to separate from the back of the wings, which caused a very clear and perceptible vibration, known as buffet. The resultant increases in G-force inflated the anti-G trousers, squeezing my legs and my lower abdomen: another new sensation for me. It was great to be zooming around considerable amounts of sky in such a responsive and exciting jet.

Probably because I was enjoying myself too much Duncan said, ‘OK, let’s fly straight and level at 300kt.’

I duly adjusted everything and then Duncan reached out and selected two double-pole switches from the up position to down. The controls stopped working. The control column became a rigid rod sticking up out of the cockpit floor.

‘That’s what it’s like when the hydraulics fail,’ explained Duncan. ‘Now try a turn.’

I forced the stick to the left and pulled slightly to hold the nose up and stop the jet descending. ‘Roll into a turn to the right,’ came the next instruction. I had to use both hands to do that. A gentle chuckle with a slight South African accent emanated from the right-hand seat. Eventually we slowed down, dropped the undercarriage and then the flap and manoeuvred some more. After five minutes of this my arms were getting tired, particularly after dealing with the changes of trim with the flaps moving up and down.

‘Right, that’s enough,’ Duncan said. ‘Switch the hydraulics back on and we’ll go home and do a few circuits. On your next trip you’ll do much more of that. I would have thought that a Canberra pilot would have found that flying in manual2 quite easy.’ My wry look at him across the cockpit was sufficient answer.

Soon enough I flew the Hunter T7 again, with lots of manual flying and practice of the forced landing pattern onto the airfield; no landing this machine in fields like I had practised and taught in the Chipmunk! The Practice Forced Landing (PFL) was quite a plunge at the ground starting at about 6,000ft over the upwind end of the runway and ending with a rapid and steep descent at the other end. Once the flaps were fully down it was very easy to unintentionally initiate a wing rocking motion and firm but careful use of the stick and rudder was the only way to stop it.

I was also introduced to something called the One-in-One radar guided approach, used when the engine has failed and the weather precludes the visual PFL overhead the airfield. This involved matching the distance to touchdown given by the controller with the height: 1,000ft for every mile. No great mental strain then, but plenty of physical strain flying it in manual. Nevertheless, I must have done everything to my mentor’s satisfaction because, a week later, I walked into the Ops Room and found my name on the programme board to fly Hunter F6A XE 587.

I had already been warned to read up the Pilot’s Notes and so I felt ready to take to the air for the very first time in a single-seat jet. As I walked out to the pretty red and grey painted fighter I felt like a kid in a sweet shop. I made sure that nothing was obviously amiss, that it had the right number of wings and wheels and then climbed the short, narrow ladder to get aboard. After the ground crew had helped me strap in I took a minute just to look around the cockpit. Some things were very familiar, some new. There was a switch marked BRIGHT/DIM. I didn’t know what it did but I set it to BRIGHT; I didn’t want to be dim today. The starting system was different in that it did not use cartridges but AVPIN, a very volatile liquid. I had experience of this system when I had flown the Canberra PR9, which had the more powerful Avon 206 engines. The Hunter 6 also had more thrust than the T7, another thing to look forward to.

After start-up, with the engine idling nicely and all the electrical and hydraulic systems checked I put my oxygen mask on and switched on the microphone. Oh, no! I thought. The wretched thing’s not working. I can’t hear myself. I hate it when the jet’s all ready to go and something breaks!

Nevertheless, I thought that I’d call for a radio check with the control tower. As soon as I pressed the transmit button on the throttle I could hear myself talking. The controller came back immediately with, ‘Tester 70, you are loud and clear.’

Of course! This jet doesn’t have intercom. Why should it? Idiot!

After that I just got used to not hearing myself as I ran through the checklist. Soon enough I was lined up at the beginning of runway 24, ready to slip the surly bonds of earth in a really meaningful way. I opened the throttle to about 80 per cent of full power, released the brakes and then put the throttle on the front stop. Two things happened: first an awesome howling noise emanated from just outside the cockpit and then we set off down the runway like a scalded cat. Both effects were due to the bigger Avon engine and the lighter weight of the single-seat model of the Hunter. I was up and off in no time. I climbed out to the west and proceeded to have a wonderful time! I did all the things I had been briefed to do and, after forty-five minutes of unbridled enjoyment, landed. As I turned off the runway and despite the fact that I could not hear myself I shouted, ‘What have I been doing for all these years when there were jets like this to fly?’

The following day I flew a second sortie in the F6A. It was just as much fun as the first, although my first attempt at a PFL in manual was hardly text book; but I would have landed safely eventually and probably stopped just before the end of the 10,000ft runway! After a relaxing trip in a T4 Canberra, for which the management had decided that I didn’t need a dual check, the time for the official start of our course was getting imminent.

Notes

1 As described in Follow Me Through published by The History Press, 2013.

2 ‘Manual’ was the term used when the hydraulic pressure to the flying controls was not available.

2AND SO TO SCHOOL

Monday 3 February 1975 was the first day of that year’s ETPS graduate courses. There were actually three courses running concurrently. In 1975 they were: No. 34 Fixed Wing (FW) and No. 13 Rotary Wing (RW) for the pilots and No. 2 Flight Test Engineer (FTE) course for a handful of scientific civil servants. All three courses would finish on Friday 12 December. That seemed so far off as to not be worth thinking about. Stamina was going to be a key to survival. We had all been instructed to gather at the Officers’ Mess at 8.30 a.m. from whence we were to be transported by coach to the ETPS Ground School building. This would be the only time that we would be afforded such luxury. From the next day onwards it would be bicycles, cars or Shanks’ Pony. Some of us, the ‘Select Few’, had already been together over the past three weeks, getting our brains sharpened through the ministrations of Wg Cdr ‘Chalky’ Rodgers and his staff. Now we were all together, settling into our desks for the next nine months or so. There was the usual plethora of formalities to be completed and, at 10 a.m. promptly, we were greeted by a series of the great and the good of Boscombe Down.

It is worth explaining how this large and diverse organisation worked in the mid 1970s. At the top of the tree was a senior RAF officer, the Commandant, an experienced test pilot and at that time Air Commodore A.D. Dick, OBE, AFC, MA. He represented all the military services’ involvement in the establishment’s work in the assessment and development of air vehicles for the three armed forces. He worked alongside a senior scientific civil servant known as the Chief Superintendent, who wasn’t a policeman, but oversaw and took responsibility for all the scientific work of the establishment. And that bore the grand title of the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE or colloquially A²E²), even then a somewhat archaic title, as the establishment dealt with all types of aircraft, not just aeroplanes, and there was not much in the way of experimental flying done there any more. That was more the preserve of the various RAE sites across the UK.

ETPS had its home at Boscombe Down and the Establishment provided all the facilities it needed. In the chain of service command down from the Commandant was the Superintendent of Flying, an RAF group captain, and the three test squadron COs, who were all wing commanders, or other services’ equivalents. ETPS was under the supervision of its OC who was, at the time, an RAF group captain. All the customary support services for military personnel at Boscombe Down were provided by the RAF Unit and commanded by an Administration Branch RAF squadron leader.

After listening politely to the CO of ETPS, Gp Capt. Alan Merriman, the CTFI, Wg Cdr Wally Bainbridge and, last but by no means least, the Chief Ground Instructor, the aforementioned Wg Cdr John Rodgers, we started a whole new round of interviews. The first was with Gp Capt. Merriman, who had already grilled me twice before, when I had attended the ETPS Selection Boards in 1973 and 1974! Still, it was nice to chat again in a much more relaxed atmosphere. He was friendly in that special way that senior officers have of making you feel simultaneously at ease but keeping you aware that you are in ‘the presence’. When he asked what my ambition for the course was I answered, ‘To be at the McKenna Dinner, sir.’3

That evening we all met up in the Officers’ Mess for a ‘Meet and Greet’ with all the staff. There were guys from many nations among the student body. From the USA was Lt Cdr Tom Morgenfeld, a US Naval Aviator fresh from flying the F8 Crusader. With his black hair and moustache, Tom had a look reminiscent of a Mexican bandito; which was very strange considering that he was from upstate New York and had a German surname! From Denmark was Capt. Svend Hjort, an F-100 Super Sabre driver; a real fair-haired Scandinavian with a fighter pilot’s blue eyes and lantern jaw. Then there was a French fighter pilot with an excess of Gallic charm and a total lack of Gallic hair – Commandant Gerard Le Breton, lately from a Mirage F1 squadron of the French Air Force. Gerard would soon become the focus of attention of most of the wives and girlfriends whenever he walked into a room! Later in the course he would turn things around by bringing his excessively beautiful French wife over; then it was the boys’ turn to gawp! There were also two guys from Germany, both civilian German Ministry of Defence pilots – Udo Kerkhoff and Eddie Küs. Udo was a very amusing and amiable chap with a mop of blonde hair that was rarely in good Teutonic order. Udo was a transport pilot latterly with the Franco-German Transall. Eddie was a good-looking but follically challenged helicopter pilot. Another pair who shared their nationality were Indian Air Force pilots ‘Rusty’ Rastogi and P.K. Yadav, both from MiG-21 squadrons. Then there was an Italian, Bruno Bellucci, who had come from the F-104 Starfighter but was actually going to become a helicopter test pilot. I think that all the Fixed Wing students felt very sorry for Bruno; it was going to be hard enough doing the course in another language, but to also have to learn a whole new way of flying at the same time was a very big ask! The final legal alien was our Antipodean, Fg Off (yes, a Flying Officer) Mark Hayler RAAF, ex-DHC Caribou and Mirages; a good background to come here and fly the variety of aeroplanes we were going to use. He was also my next door neighbour on the married patch.

Then there was the RAF contingent. Apart from myself there were two ex-Lightning pilots, Flt Lts Vic Lockwood and George Ellis, and you soon learn that you can tell a Lightning pilot – but you can’t tell him much! George was our youngest RAF course member and had only just acquired the minimum number of hours to qualify to be here. However, he was a bit of an academic star, being a Wickhamist and Oxford graduate. George affected his exceedingly English image by the wearing of a deerstalker hat, plus-fours and waistcoats with a pocket watch on an Albert chain. His party trick was to twirl the glittering timepiece around and then catch it in one of the waistcoat pockets. This usually brought loud acclamation from the ‘foreigners’. Tom Morgenfeld gave George the sobriquet of ‘Mad Dog’, taken from the title of Noël Coward’s song ‘Mad Dogs and Englishmen’!

The other Brits were an ex-Canberra and F-4 Phantom driver, Flt Lt Chris Yeo, and a ‘Jump-Jet’ Harrier man – Flt Lt Roger Searle. From the V-Force world, a Scottish ‘Flying Flat Iron’ Vulcan pilot, Flt Lt Duncan Ross, and two helicopter guys, Flt Lt Terry Creed and Sqn Ldr Rob Tierney. Terry was a dead ringer for the missing Lord Lucan and it became de rigueur to proclaim this loudly when we were in public places. Due to his elevated rank Rob was made the Course Leader. As is befitting, I have saved the Senior Service representative to the last among the pilots: a smooth operator called Lt Simon Thornewill RN and yet another Rotarian. Then there were our four civilian FTE aspirants – Neil Sellers, Dave Morgan, Rob Humphries and Jerry Lambert. I had already flown with Jerry in the Canberra, when he occupied the right-hand seat of the T4; he hadn’t seemed all that taken with aviating.

But all that flying experience would be put on hold for three weeks of all-day classroom lessons. We were to be put through a rigorous introduction to a wide variety of subjects: from the composition and characteristics of the atmosphere, units of measurement, basic aerodynamics, stability derivatives, the solution of polynomial equations, the fundamentals of aircraft design and many more such esoteric topics. It rapidly became like an intense first year university course crammed into three weeks, and no time off between lectures.

‘Chalky’ Rodgers didn’t operate solo. He had a small but excellently qualified support staff. The first of these was Sqn Ldr Brian Johnson, an education officer who specialised in matters aerodynamic and mathematical, especially the mysteries of non-dimensionality. Vic Lockwood later observed that to measure non-dimensional time we would need non-dimensional watches and the RAF didn’t issue us with those. The other ground instructor was a navigator, Flt Lt Harold ‘Wedge’ Wainman, the Systems Instructor. He had been a navigator on my first squadron, No. 16, in Germany in the mid 1960s. I had known him well there and we had survived a Winter Survival Course together. Wedge taught us all about magic black boxes and how they and their computerised innards worked.

So our amble, at the speed of light, through the fertile fields of scientific academia continued apace. At the end of those first three weeks we felt like there had never been any other existence. I was getting thoroughly bored with the view from the window by now, and it never gave me the inspiration for the questions racing through my head. But there were lighter moments. One morning during a lesson examining the relationship between Imperial and Standard International (SI) Units, French fighter pilot Gerard Le Breton, who sat immediately in front of me, was thumbing frenetically through his petit dictionnaire. He did that a lot because the French Air Force kept his posting to England a secret until the last minute, so he had received no English language training! He turned round to me and asked in a whisper, ‘Why eez a small animal from ze garden used to measure force?’ He had looked up the word ‘slug’!4

Then one afternoon, during one of his by now famous high-speed blackboard rolling sessions, Chalky asked, ‘Now how do you think that we could eliminate this variable?’

‘Rub it out?’ came the reply from Vic Lockwood.

It’s funny how time flies when you are having so much fun and so on our third Friday we were subjected to a progress examination; it was actually more like a speed writing test. From now on we would attend Ground School for one or two periods each morning and after that it would be up to the hangar and flying! However, it still being Friday, we all repaired to the Officers’ Mess Bar for Happy Hour. I believe that was when we hatched a plot for future Fridays. It was decided that we would instigate Pot Luck Suppers, with our wives each producing a dish of something delicious and representative of their national origins. Fortunately a large majority of our better halves were in favour, so one of us would, each week, volunteer our Officers’ Married Quarter (OMQ) as a venue, and the guys would arrive with the booze! Magic!

Notes

3 The McKenna Dinner was the graduating event held at the end of the course and named after Sqn Ldr J.F.X. ‘Sam’ McKenna. He was an eminent pre-war test pilot with the A&AEE at Martlesham Heath and, in 1944, was appointed as Commandant of ETPS. He was killed in an accident in a P-51 Mustang when an ammunition box left the aircraft and one wing subsequently detached. The aircraft crashed close to Boscombe Down.

4 A slug is an imperial unit of force.

3A PLETHORA OF PLANES

Finally we were going to get to grips with some aeroplanes! Resplendent in our bright orange flying suits, small teams of us could be seen crawling over various examples of the School’s flying machines. Initially this was for our first written report – the Cockpit Assessment. I, along with a couple of others, had been directed to assess the flight deck of the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy: a transport aircraft and the last aeroplane to be designed and built by Armstrong Whitworth. The Argosy was adopted by the RAF in the early 1960s and had a freight carrying capacity of 13 tonnes; it could also be used by paratroopers. The flight deck crew consisted of two pilots, a navigator and a flight engineer.

We pored over the pilots’ bit of the cockpit and assessed its utility. We measured the field of view through the letterbox-like windscreen and side windows. We checked the escape facility, via a long rope, which we deigned to use, as it was about 20ft from the window to the ground! We looked at all the dials, switches and levers and their layout. We assessed the static qualities of the flight controls system, looking for such esoteric characteristics as breakout force, centring, running friction and backlash. To do these things we had each been issued, along with our voice recorders and kneepads on which to carry test cards and make notes, various implements that looked like medieval instruments of torture. These tools helped to measure forces and deflections of the control systems. In addition to these we had been able to hone our skill at estimating control forces using an old Hawker Sea Hawk cockpit set up in the ETPS Hangar for just such a purpose; once we had been introduced to this simple but effective apparatus a queue of guys waiting to use it soon formed! After we had finished our Cockpit Assessments we wrote our individual reports and handed them to our tutors for their assessment of our assessments. During the course we would each have three tutors. The course was split into three terms: the first up to the Spring Bank Holiday, with a week’s leave to follow, and the second up to the end of July, after which there would be three weeks off!

My first term tutor was to be Sqn Ldr Graham Bridges. He had done a tour on the Canberra PR9 with No. 13 Sqn in the Mediterranean and had been a test pilot at Farnborough. Graham took four of us under his accommodating wings and started us on our journey of discovery into the mysterious world of test flying. Alongside me in Graham’s syndicate were pilots George Ellis and Gerard Le Breton, and FTE Neil Sellers. Once we had converted to type, Graham would be the one to brief us and demonstrate in flight the required test techniques, as well as use his red pen to constructively criticise our reports; aka ‘rip them apart’! Reports had to be handed in no later than ten days after the final test flight of the topic to be examined. Then the reports would progress from the Tutor, to the CTFI and then to the CO for each to make their comments, each with different coloured ink. It really was a school! Graham was a bouncy sort of character and full of boyish enthusiasm. He possessed a good pair of lungs and his laugh and more sarcastic comments could be heard clearly emanating from his office or the Ops Room, all the way down the long corridor to the coffee bar in the crew room. This was Graham’s final year on the school, so he was also the Principal Tutor Fixed Wing (PTFW), which meant that he had the unenviable task of organising each day’s flying programme. This had to satisfy the needs of the syllabus and match student progress with tutor and aircraft availability; and there was the English weather to be taken into account.

Apart from Graham Bridges and the aforementioned Duncan Cooke, the other two members of the Fixed Wing Tutorial Staff were Sqn Ldr Peter Sedgwick RAF and Lt Cdr Walt Honour USN. Like Duncan, Peter originated from the southern hemisphere – the Falkland Islands – and had joined the RAF and become a transport pilot. He had spent a tour at Farnborough as a test pilot before returning to ETPS to educate and torment folk like me. Walt was the nominal American in the permanent exchange appointment with the US Navy Test Pilot’s School at Patuxent River in Maryland, USA. He had flown the LTV A7 Corsair operationally and tested the Lockheed S3 Viking for the US Navy. A crucial character, who worked alongside the Tutors, was the ETPS QFI, Sqn Ldr Mike Vickers. Mike was one of those people whose experience was written all over his face. He was older than the rest of the staff, indeed he had flown during the Second World War. For a part of that time he had flown Hurricane fighters from naval fleet support ships. This was on what now seems like a crazy, almost kamikaze-like scheme, where the Hurricanes were launched from catapults on ships that had no landing decks. After flying their defensive fighter missions the pilots then had to find their way back to the vicinity of one of the ships and land in the sea! I cannot believe that anyone would have volunteered for that tour of duty. But Mike survived to fly another day and stayed on in the RAF post-war to become a jet fighter pilot and instructor. It would be Mike’s dulcet tones and calm instructional manner that would get us through many of the all too short conversion sorties.

Before we started each test flying exercise we had to be checked out on each aircraft type. My first one was the Jet Provost T5; aka ‘JP5’. It really was a re-familiarisation for me, as I had flown the T3 and T4 versions during my basic flying training and the T5 when I was at the CFS. The ETPS JP5 XS 230 was an interesting aircraft. It was the second prototype of the mark and had been converted from a T4; its sister ship XR 229, the first prototype, had been lost in an accident during development flying. XS 230 had never been used for flying training, other than at ETPS, and had several slightly non-standard features. We would use it for stalling test exercises this term and spinning next term.

My next conversion was to the propeller-driven Beagle Basset: an odd little dog and an odd little aeroplane. It was similar in size to the Hunter but, as a light communications aircraft, obviously quite different. There were two 310hp Rolls-Royce/Continental engines mounted on the wings and a cabin that could accommodate five people including the pilot. The Basset had first flown in 1961 and then a military version, the CC1, had been developed for the RAF. Twenty examples of this model were built and they were equipped with a new entrance door incorporating steps down from the rear of the cabin; these were known as the Air Stairs. Possibly because they had been designed so that air-rank officers could dismount gracefully while wearing their full regalia including a sword! The Basset CC1 entered service in 1965. ETPS had two Bassets and the one that was not modified to take the Variable Stability machinery was XS 742. It had briefly been on the Royal Flight, when Prince Charles had been taught to fly a multi-engined aeroplane.

With two people on board the Basset’s performance on take-off was hardly startling. One wondered whether it would climb after an engine failure near the ground or whether one would just have to steer it to a crash landing somewhere near the airfield. Goodness knows what it was like on a hot summer’s day with full fuel tanks and all the seats occupied. But once it was safely away from the ground it slipped along quite well. It also handled nicely, the forces on the manually operated controls being reasonably light and well balanced. The cockpit was not a bad place to work either, with a great view, fairly spacious and well laid out and with a control yoke instead of a stick. The only thing I remember being tricky was the landing. That was because the tailplane and elevator sat in the slipstream from the propellers and there was not quite enough elevator authority at low speeds to keep the nose up. So if I closed the throttles smartly just before touchdown the little beast tended to drop out of the sky, nose first, while I tried desperately to stop it by applying lots of pull on the yoke, usually to little effect. I learnt to take lots of nose-up trim during the final approach and slowly reduced the power as we got close to the runway. It still didn’t guarantee a nice, smooth arrival – but it stopped the nose-down lurch and the naval-style arrival! With the Hunter, Jet Provost, Canberra and Basset under my belt I had just two more aircraft types to attack: the Argosy and the Lightning – the ridiculous and the sublime!

Conversion to the Lightning would not come until much later in the term so it was now time to tackle the Argosy. I had a bit of a head start because I had, along with the others in my syndicate, already become very familiar with the flight deck of the big beastie. But that was with it sitting stationary on the ground. Now we each had only two flights, totalling all of three hours, to qualify to act as captain. I had never before flown a four-engined aircraft or operated turboprop engines. The Argosy had four of them, Messrs Rolls and Royce’s excellent and pioneering Darts, as installed on the UK’s first and enormously successful turboprop airliner, the Vickers Viscount.

The Argosy was known by all and sundry as the ‘Whistling Wheelbarrow’; a reference to the high-pitched, ear-piercing whistle of the R-R Darts, the Argosy’s twin, handle-like tail-booms and its tendency to land on the nose wheel at the slightest provocation. Some cynics said that the Argosy had been made out of other people’s leftovers. It was reputed to have wings of the Avro Shackleton with Meteor rear fuselages used as the tail-booms. It could have been true! Messrs Armstrong and Whitworth manufactured both aircraft types at one time or another! We also learnt that when the Argosy was first tested by the RAF the floor was not strong enough to take the Saracen armoured vehicle, for which it had been procured. Unfortunately, strengthening the floor increased its thickness, which meant that there was now insufficient headroom in the freight bay to get the said piece of Army kit aboard! Moreover the resulting extra weight cut the total load carrying capacity so much that the range with the required maximum weight was now less than the specified requirement! Hence those aforementioned cynics said that the Argosy could carry a maximum volume load of table tennis balls to Cyprus or a maximum weight load from RAF Brize Norton to RAF Lyneham! We were learning how to be very cruel, but not yet very objective.