Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ylva Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

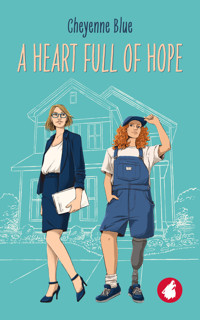

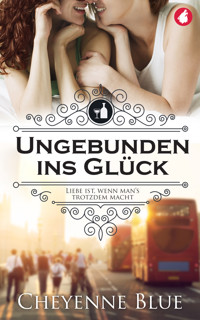

A captivating opposites-attract lesbian romance about a city woman discovering her country heart. Australian country girl Nina Pellegrini runs a program for city kids to experience a taste of rural life at Banksia Farm. But when a child is hurt and a lawsuit threatens, Nina is determined to find the best legal assistance to help her save the farm. Enter high-flying lawyer Leigh Willoughby, whose city world is far from the farm's chaotic mix of kids and animals. She certainly doesn't have time for small cases that don't pay or farm visits that wreck her cool—and her clothes. Still, the warm-hearted Nina and her challenging, twelve-year-old daughter, Phoebe, are awfully hard to say no to. What on earth has she gotten herself into? A captivating opposites-attract lesbian romance about a city woman discovering her country heart.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table Of Contents

Other Books by Cheyenne Blue

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Epilogue

About Cheyenne Blue

Other Books from Ylva Publishing

Sign up for our newsletter to hear

about new and upcoming releases.

www.ylva-publishing.com

Other Books by Cheyenne Blue

Code of Conduct

Party Wall

Girl Meets Girl Series

Never-Tied Nora

Not-So-Straight Sue

Fenced-In Felix

Girl Meets Girl Collection (box set)

Acknowledgements

Here we go again, another book out in the world. A Heart This Big is my seventh novel or novella to fly free. Take it from me—it doesn’t get any easier.

Once again, I send huge thanks to the team at Ylva Publishing: Astrid, of course, my wonderful editor Sandra Gerth, copyeditor Miranda Miller, Glendon at Streetlight Graphics, and all those working behind the scenes. I consider myself very lucky to work with a team who gives my work so much care and attention.

For this book, I again called upon my fellow author and friend Katharina Marcus, who this time not only cast an eye over the horse parts but also brought her experience with the Riding for the Disabled program. Along the way, she also taught me a thing or two about twelve-year-old girls. After all, it’s been decades since I was one. My great mate Marg also weighed in on the kids and went on her usual thorough scavenger hunt for typos. Thanks to Ameliah Faith for the beta read and enthusiastic cheerleading and to Sophie Lennox for the sensitivity read on the character Edwina. Finally, a shout-out to the lawyers I work with in my day job, who cheerfully answered my seemingly random questions—although they still have no idea why I was asking!

Cheyenne Blue, Queensland, Australia

Chapter 1

Nina set down the wheelbarrow, rotated her tight shoulders, and indulged in a moment of pleasure watching her daughter.

Phoebe walked alongside Mr Petey, holding the grey pony’s lead rein close to the bit as she’d been taught. Mr Petey plodded docilely around the paddock, ears flicking back and forth as he listened to Phoebe’s voice. Mr Petey’s rider, Billy, clutched the saddle with both hands. His red T-shirt was a little too small and showed a strip of chunky tummy between it and his pants.

“Try and sit a little straighter, Billy.” Phoebe’s clear voice floated back to Nina. “Mr Petey will be more comfortable if you do.”

Billy jerked to attention like a soldier, making Nina smile.

“Phoebe’s good with the little kids. You wouldn’t think she’s only twelve herself.” Stella stood next to Nina. Straw stuck out of her wispy hair, but her hands were as clean as ever, her nails manicured.

“Yes, she is.” Nina allowed herself a moment of pride before turning back to the wheelbarrow.

Stella, however, continued to watch her son, her work apparently forgotten.

Nina sighed. If only Stella would show the same commitment Phoebe did. “Can you take that wheelbarrow to the muckheap and empty it, Stel?”

Stella wrinkled her nose. “I don’t know.” Her gaze went back to Billy, who was now urging Phoebe to let him trot.

“Remember, I showed you how last time.” Nina managed a reassuring smile for Stella before she turned and marched off to the barn. Exactly how had Stella thought she could help at Banksia Farm when they struck the deal? She was scared of the animals and attempted any physical chore in a very half-hearted manner. Nina sighed. Billy and his obvious love for the animals had won her over, and Stella was part of the package.

Stella trailed behind her. “What do you want me to do?”

Nina shot a glance at the still unemptied wheelbarrow and quashed her short reply. If Banksia Farm was to gain anything from Stella’s “assistance”, Nina had to come up with something Stella was able to do. The dollars she could have received if a paying child had Billy’s place in the Barn Kids program flashed through her mind, but she pushed the thought aside. No, she would always make room for the Billys of this world, even if their parents couldn’t pay or were useless around the farm. She grabbed the ponies’ hay nets and stuffed them with more force than necessary.

Stella stood in the doorway, twirling a strand of hair around her finger.

“I’ve been thinking.” Nina summoned a smile. “How about I show you what’s involved in manning the farm shop? It’s a pleasant task. You just have to sell the farm produce to visitors.”

“Would I be by myself?”

“Not at first. I’ll show you what you need to do, but once you’re confident, I’ll leave you to it.”

“I don’t think I’d be very good at that. I’m not that good at talking to people.”

“Why don’t you give it a go at least?” Even in her own ears, Nina’s voice sounded artificially encouraging. “Most of the volunteers love working there.”

“I’d rather not, if you don’t mind.” Stella came further into the barn.

Nina saw the flash of apprehension in Stella’s blue eyes and quashed a snappy reply. It was hard for Stella as a single parent. She always seemed so diffident, so lacking in confidence. That was another reason Nina had agreed to take Billy into Barn Kids—maybe being around Banksia Farm would benefit Stella too.

“No worries, then. You don’t have to do anything you’re not comfortable with.” She was running out of options for Stella, though. She handed her the hay nets. “Can you hang these in Mr Petey’s and Jellybean’s stalls? Remember the knot I showed you? Use that.”

“I think so.” Stella took the hay nets and wandered off.

Nina heaved a sigh of relief. Hopefully, Stella would hang the nets correctly. She would have to check later. She strode back to the ignored wheelbarrow and pushed it to the muckheap. With economical movements, she forked the soiled straw and manure onto the top of the heap.

Luckily, it was a quiet day at Banksia Farm. Most of the regular Barn Kids were at school, but Phoebe and Billy’s school had a kid-free day.

There was no sign of Stella. Nina walked down the barn until she caught sight of Stella’s bright cotton frock in Jelly’s box. Stella was wiping something from her sandal—the unsuitable open-toed sandals Nina had told her not to wear—and the hay net sat lopsidedly on the floor. Without a word, Nina went in and hung it up.

“I’ve trodden in something that smells bad.” Stella balanced on one leg as she inspected the bottom of the other sandal. “Where can I wipe it?”

“On the straw.” Nina’s voice was as pleasant and even as she could make it. Really.

Stella overbalanced, and her foot went down in the straw. “Oh no. I trod in something again.”

Nina clenched her jaw so hard her teeth ached.

The door of the barn crashed open. “Mum, where are you?” Footsteps thudded on the concrete. “Mum?” Phoebe’s voice cracked with panic.

“I’m here, Phoe. Where’s the fire?” Nina’s pulse raced with a mother’s concern, and she stepped out of Jelly’s stall.

Phoe skidded to a stop. Her eyes were wide, and her complexion was unnaturally sallow.

“What’s happened?” Nina’s gaze darted over her daughter from head to toe. Blood. Was there blood? Nothing obvious. But what then? She gripped Phoebe’s shoulders, willing some words out of her.

“Billy fell off. I think he’s hurt his arm, and he’s talking funny.”

Oh shit. Nina shot a glance at Stella, and she struggled to keep her voice calm. “You did good fetching me, Phoe. Where’s Billy now?”

“Sitting on the ground in the paddock. He says he wants rissoles for dinner and Superman is riding Mr Petey to the airport.” Phoebe’s voice was husky as if with unshed tears.

Worry jumped in Nina’s stomach. “Let’s go see.”

Stella and Phoebe had to jog to keep up with Nina’s swift steps.

“Billy often talks nonsense,” Stella said. “I’m sure he’s fine.”

Nina shot her a glance. Stella was no helicopter parent, but her airy unconcern seemed a little callous.

Nina’s glance swept around the paddock. Mr Petey grazed on the far side by the road. His reins trailed on the ground.

Her gaze snapped to Billy. He sat hunched over, and one hand held the other arm. What seven-year-old ever stayed still like that unless he had to? Unless he’s badly hurt. Nina swallowed hard against the panic that bubbled in her throat. “Phoe, catch Mr Petey and put him in the barn. Then fetch one of the pony rugs and come back as fast as you can.”

Phoe nodded and went off at a run.

Nina hurried over to Billy and crouched. “Hey, mate. What’s the matter?”

Billy gazed up at her, his eyes unfocussed. “I fell out of the sky. My arm hurts.”

“Can I have a look?” Nina forced a smile.

Billy shook his head. “Nah.”

Stella crouched too and gently brushed Billy’s hair from his forehead underneath the riding helmet. “Can Mummy look?”

Billy nodded and bit his lip.

When Stella lifted Billy’s hand from his bad arm, it was bent in a way that no normal arm should be.

“Oh,” Stella said, her voice small. She jerked back.

Nina glanced at her. Stella was milky white and washed-out. She didn’t want two casualties on her hands. She fought down a wave of queasiness. Focus. Was the broken arm Billy’s only injury? What should she check? Another deep breath steadied her, and her first-aid training jumped back into her head. “Billy, do you know where you are?”

“I’m at the farm. Mr Petey and I were flying really high. Then a cloud fell on us, and Superman said Mr Petey had to take him home. Superman pushed me off.” He pointed upward. “Why is the sky green?”

Nina met Stella’s eyes over Billy’s head. He was an unusual kid with a vivid imagination, but this was weird talk, even from him. Sweet baby Jesus, please not a head injury.

Nina peered into Billy’s eyes. What was she looking for? Think. His pupils—that was it. She glanced from one to the other. They looked to be the same size, but it was hard to be sure. “Did you hit your head?”

“My head hurts.” Billy whimpered and leant back into Stella’s arms.

That was enough. A broken arm was one thing, but a head injury could be serious, particularly in a child. Nina stood, fished her phone from her pocket, and glanced at Stella, who had regained her colour but still looked fragile and unsure. “Stel, we need to call for an ambulance. I’m going to step over here to make the call, okay?”

Stella stared at her for a moment, then her hunched position unfurled. “I’ll stay with my kid.”

Nina nodded and smiled at Billy. “I’ll be back in a moment, Billy-the-Kid. Phoe’s gone to get you one of Mr Petey’s rugs to keep you warm.”

She stepped a couple of paces away and faced Billy while she lifted the phone to her ear. Stella sat on the ground, cradling him to her chest and singing softly.

The Triple Zero operator was calm and efficient and, after the initial questions, said an ambulance was on its way.

“Ask him some basic questions,” the operator said. “Keep him talking.”

Nina returned to Billy’s side and crouched. “So, my little mate. What’s your name?”

Billy looked up at her. Tears sparkled in his eyes and tracked moisture down his dusty cheeks. “William Robert Placido Moran and I live at 52 Lorikeet Close, Linville, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, the world, the universe.”

“Spot-on.” Nina smiled at him. “How old are you?”

“I’m seven years, one month, and eleven days. My mummy’s thirty-four years, five months, and fifteen days. Where’s Mr Petey?”

“Did you hear that?” Nina said into the phone. “Billy doesn’t normally slur like that.” To Billy, she said, “Mr Petey’s gone home for his dinner.”

Phoebe returned at a jog, a horse rug in her arms.

Nina draped it around Billy, careful to avoid the broken arm.

“Is there any blood or clear fluid in his ears?” the operator asked.

Nina shifted to look carefully. “Not that I can see. Should I remove his helmet?”

“No, leave it. The ETA for the ambulance is four minutes. Keep talking to him and watch in case he falls unconscious.”

“How are you, Stella?”

“Okay.” Stella tightened her arms around Billy’s chest. “I’ll be better when Billy is.”

Billy whimpered. “Stop squeezing me, Mummy. It hurts.”

Stella loosened her grip. “Sorry, sweetie. Mummy’s just looking after you.”

A mother protected her young. Nina swallowed down the worry. Hopefully, Billy only had a broken arm and a minor concussion and nothing worse. But what did she know?

Nina peered into Billy’s eyes again, searching for any change.

He stared back at her, his blond hair flattened on his forehead under the helmet. His blue eyes were wide and apprehensive.

“The ambulance should be with you in three minutes,” the operator said. “Is there someone who can stand on the road and flag it down?”

Of course. She should have thought of that. “Phoe, run to the end of the drive and wave at the ambos when you see them. Leave the gates open on your way so they can drive straight through.”

Phoe nodded, then took off at a run, her skinny limbs flying over the rough ground.

“You want to ride in a big, white ambulance, Billy?” Stella said into his ear.

“Will the lights flash? Will it make the whoo-whoo noise?”

“I’m sure it will, just for you.”

“Good.” Billy’s voice slurred.

Sirens sounded in the distance. “Hear that, Billy?” Stella said. “They turned them on for you.”

Billy gave a weak grin. His eyelids fluttered.

The sirens stopped. A minute later, the ambulance bounced its way across the rough grass. Phoebe ran behind and came to stand next to Nina.

Nina glanced at her. This was scary enough for her. How was Phoebe managing?

Her daughter’s lower lip trembled, and tears sparkled on her lashes.

Nina squeezed her hand. “Billy will be okay.” Please let that be true.

Two paramedics exited the ambulance. One crouched next to Billy. “Hey, big fella. What happened to you?”

“I fell off Mr Petey. I think his wings stopped working.”

“Well, that’s not good. My name’s Brett. What’s yours?”

“William Robert Placido Moran. I feel sick.” Billy wiggled out of Stella’s arms and emptied his breakfast over Brett’s shiny boots.

Brett didn’t budge. “Let’s take a look at you, William Moran.”

His colleague opened the back of the ambulance and wheeled out the trolley. “We’ll take him to the university hospital,” she said to Stella. “Will you ride along?”

Stella struggled to her feet, brushing grass seeds from her dress. “Yes. Of course.”

Nina stood to one side as the female paramedic asked questions of Stella. Concern for Billy welled up once more, and her guts twisted. What if it had been Phoe who sat pale and sick, clutching a broken arm and spouting nonsense? She’d have been beside herself with anxiety. Stella, for all her vagueness, was handling this well, maybe better than Nina would have if it were her kid.

In no time, Billy was loaded, and Stella climbed in the back alongside him.

“I’ll call you later,” Nina called. “See how he’s doing.”

Stella nodded.

The ambulance crawled down the paddock to the gate and out onto the road.

Nina blew out a deep breath. Billy was now in the best hands. She forced a smile. “Why don’t you and I have a long drink of lemonade after all that? We can call Stella later to see how Billy is.”

A tear slipped down Phoebe’s cheek. “Will he be okay? Will he?”

Nina wrapped one arm around her. “I’m sure he will be, sweetie. Broken bones heal quickly when you’re little like Billy.”

Phoebe’s shoulders hunched, and she pushed away from Nina’s side. “Was it my fault?”

“No. Definitely not. It was an accident. That’s all. It wasn’t Mr Petey’s fault either.”

“I’ll go and pour the lemonade.” Phoebe turned away and walked towards the house.

Nina took a pace after her, and her glance fell on the still open gate. She jogged across to close it.

A car door slammed nearby.

When Nina turned, she tightened her lips, and a spark of anger ignited in her belly. Just what she needed.

Jon Wakefield’s dapper grey suit was as immaculately pressed as if he’d just picked it up from the drycleaners. Which he probably had. He approached her, detouring around the rutted dirt. His gaze followed the ambulance speeding along the road. The sirens came on in a blaze of sound, probably at Billy’s request.

“Trouble in paradise?” He switched his gaze to her face.

“No.” Her smile stretched her lips in an insincere grimace.

“It looks like there is. An ambulance leaving here in a hurry.”

She shrugged. “Everything’s fine. Just a routine precaution.” Oh, how she hoped those words were true. Billy would be fine. Kids fell off ponies all the time. Kids bounced; they didn’t break. Except for Billy’s arm. Hopefully not his head.

“I’m glad to hear it.” He brushed imaginary dust from the arm of his suit. “I wonder if you’ve had a chance to consider my offer, Ms Pellegrini.”

She clenched her jaw. Did he never give up? “I have. The answer’s no. Just as it was to your previous offer and the one before that.”

“I think you’ll find it’s a generous one. Do the research.”

“I don’t need to. The answer’s still no.”

The ambulance was nearly out of sight, sweeping up the main road towards the hospital. The lights and sirens were still on. Billy must be enjoying the ride.

“Going to the university hospital?” Wakefield said. “Nothing serious, I hope.”

“No.”

“Horses are dangerous brutes.”

“Not mine.”

“Still.” He shrugged. “A lot of overheads on a big place like this. I hope you’re well insured.”

Nina moved back through the gate and closed it. It was a flimsy barrier at best between them, but the solidity and permanence of her land underneath her feet gave her confidence. She lifted her chin. “You’re wasting your time, Mr Wakefield. Please do not come again.”

He rested a hand on the gate with studied casualness. “Two million, three hundred. I think you’ll find it’s more than generous. You could do a lot with that. A fine education for your daughter. A lovely modern house to live in.”

“The answer’s no. It will always be no. I’m not selling.”

For a moment longer, his cool grey eyes studied her.

Nina lifted her chin and met his stare until he turned away.

“Don’t lose my business card. You may need it.”

The arrogant bastard. Nina gripped the gate with both hands. Nothing could make her sell Banksia Farm. Nothing.

Chapter 2

Her feet must have swelled. Maybe wearing work boots all the time had made them spread. Whatever the reason, Nina’s shoes rubbed her feet. Her left big toe seemed jammed against the end of her smart dress shoes—the only suitable pair she had for a trip to Sydney’s business district. Surreptitiously, she eased her foot from the pump and wiggled her toes. She flicked a page of the glossy magazine on her lap and glanced around the reception area.

Plush carpeting and recessed lighting enhanced the smooth timber of the expansive reception desk. No doubt it was milled from a solid slab of rainforest timber, polished to perfection by an army of third-world workers, and had cost more than Nina made in three months.

The receptionist’s gaze lingered on Nina’s bare toes, and she had a rather supercilious expression on her face.

Nina smiled at her and resisted the urge to jam her foot back into the too-tight shoe. She turned another page of the magazine and pretended to read.

“Nina Pellegrini?”

Nina looked up.

The soft carpet had muffled the approach of the big-boned, severe woman now standing in front of her. Her helmet of grey hair was cut in an angular style that did nothing to soften her look. She was dressed all in black: a black blouse with a high neck tucked into tapered, black pants, ending in soft leather shoes—black, of course.

Nina struggled out of the too-soft leather chair and tried to push her foot back into her shoe at the same time. “Yes, that’s me. You must be Leigh Willoughby.” She held out a hand, but the attempt at professionalism was spoilt when her toe caught on the carpet and she overbalanced.

The woman caught her elbow to steady her.

“I’m sorry.” Nina stooped to replace her shoe. “Thank you for seeing me, Ms Willoughby.”

“I’m Grizz Jankowski, Leigh Willoughby’s paralegal. Let me take you through.” Grizz smiled. It brought her face alive and made her seem more approachable.

Nina smiled back. Thank goodness for a friendly face after the haughty receptionist. “Yes, thank you. Of course. I should have known your name. I saw your picture on the company website.” Inwardly, she cursed her inattention. She’d studied the team photos; Leigh Willoughby was blonde and younger than her paralegal—maybe around thirty. In the photo, Leigh was smiling slightly, to inspire confidence no doubt, but the effect had still been somewhat distant and professional. Nina imagined Leigh Willoughby as tall, slender, and elegant, with obfuscating formal language—like all lawyers.

“No problem.” Grizz waited until Nina picked up her bag, and then she buzzed open a security door into the main office.

The route she used was obviously the one for clients; it bypassed the cubicles of admin assistants wearing headsets and typing at breakneck speed, and skirted rooms with desks piled high with papers. Nina craned her neck to catch a glimpse of the real world of Petersen & Blake outside of the row of glass-fronted offices and the streamlined corridor softened with artwork. The final door stood open, and Grizz led the way inside.

“Leigh, this is Nina Pellegrini.” With a professional smile at Nina, Grizz left and slid the glass door closed behind her.

Leigh Willoughby stood and came around her desk, hand outstretched.

Wow. The photos on the website, while accurate, hadn’t portrayed the gleaming perfection in front of her. Ms Willoughby was a tiny, slender woman standing maybe 170 centimetres in her high-heeled pumps. Leigh Willoughby’s blonde hair was coiffured into a tidy pleat, with not a single strand left loose. Her make-up was discreet with neutral shades on her eyes. Only her lips stood out, a dark and glossy red, like overripe berries.

Nina’s gaze swept over her from top to toe, taking in the glasses with large, black frames, and the cream silk blouse and dark skirt. Sheer tights, of course. Nina’s own bare legs, her patterned skirt, and her newest T-shirt that had seemed suitable when she had dressed that morning in her bedroom at Banksia Farm now appeared cheap and shabby. Still, this woman was her best chance, and she wasn’t going to blow it by slinking away in shame. She took Leigh’s hand.

Leigh’s clasp was firm but brief, a literal press of the flesh. She gestured to the leather chairs in front of her desk. “Please take a seat.” When Nina was seated, Leigh steepled her fingers in front of her. “Now, how can I help you?”

Nina swallowed, the words she’d rehearsed in front of the mirror that morning scratching in her throat. “Thank you for seeing me. I researched lawyers who would best be able to help me, and your name came up at the top every time.”

Leigh inclined her head in acknowledgement but remained silent.

Nina dragged in a deep breath and crossed her legs. “I’m the owner of Banksia Farm. It’s a little over nine acres—about 38,000 square metres—in the outer western suburbs. My gran left me the land, and I run it as a sort of smallholding. I also run a program called Barn Kids. It allows children age seven to twelve the opportunity to experience a slice of rural life in the city. The kids learn animal care and the chain of food from soil to table. They also learn to ride a horse.”

Leigh nodded once. Her face wore a polite expression of interest.

“Barn Kids is a paid program, but it relies heavily on volunteers. Occasionally, I’ll take on a deserving kid for free who can’t afford to pay, and in return a parent volunteers around the farm. One of those kids is Billy Moran. He’s seven. He’s not a special needs kid, but he’s a little different. A bit slower, more introverted. Seems younger than his age. Gets picked on by other kids if someone doesn’t watch out for him.” Billy’s sweet, earnest expression jumped into her head as she told Leigh more about him and the circumstances leading up to the accident.

“My daughter, Phoebe, offered to take Billy for his riding lesson. She’s done it before many times.”

“How old is Phoebe?” Leigh studied Nina’s face from behind the enormous glasses.

“Twelve.”

“I see.” Leigh picked up a pen and jotted a few notes on a blue legal pad. “Go on.”

Had that been a disapproving tone in Leigh’s voice? Surely lawyers were supposed to be non-judgemental. “Phoe’s been around horses since she was five.” She cringed at the defensiveness in her voice. She needed Leigh on her side. But her voice shook as she related the accident. Billy’s comments about Superman nearly undid her completely. She’d thought he was okay. Wanted him to be okay. Believed he would be fine.

“I called his mother that night, of course,” Nina continued. “Stella was relaxed about the whole thing. Billy’s arm was in plaster, and she said the hospital had kept him in that night for observation.”

More notes on the blue pad. Leigh’s writing was small and neat, as she was, and the pen was a proper fountain pen. Its gold cap twinkled in the overhead light.

“Billy was released the next day, and a few days later, he came back to the farm with some carrots for the ponies. Stella was there, and she, too, seemed okay. But a couple of weeks later, I got this served upon me.” Nina reached into her bag and drew out a sheaf of papers. She laid them on Leigh’s desk with trembling fingers. On the immaculate surface, the papers seemed dirty and dog-eared. There was an orange juice stain on the front page. She’d kill Phoebe later. “It’s something called a Notice of—”

“Claim. Yes, I can see that.” Leigh picked up the document and flicked through it.

Nina twisted her hands in her lap and watched as Leigh read quickly, a small line forming and fleeing her forehead.

Leigh put the papers down on the desk and picked up the pen again. “I assume you have public liability insurance? You don’t need me for this. Give the form to your insurer.”

“I have. They’ve declined to cover me since an underage child was in control of the pony when it happened. My policy states it must be someone sixteen or over.”

“I see.” Leigh’s neat writing reached the end of the page, and she flipped to a fresh one.

“I make everyone sign a waiver. Surely that will protect me.”

Leigh tapped the pad with her pen. “Most of them aren’t worth the printing costs. They don’t cover negligent acts. This alleges that you were negligent in allowing a minor to have control of a dangerous animal, that the pony is dangerous, that you should have ensured that the paddock was free from rabbit holes—”

“Do you know how ridiculous that last one is? That all of those things are? It’s a farm. I can no more keep rabbits out than I can fly.”

“Nevertheless, it’s part of the claim. Along with the defective helmet you supplied and the lack of instruction Billy received.”

“It’s bullshit.”

“Many claims are.” Leigh’s pen tapped a staccato beat. “Unfortunately, you still have to respond to it.”

“Can you help me?” Nina leant forward. She held her breath. If Leigh agreed, it would be all right.

“Yes.” Her glance flicked up and down Nina’s body. It was an assessing glance; Leigh was judging her worth and her ability to pay, of that she was sure.

“So you’ll take me on?” Nina’s shoulders relaxed, and her body sagged as the tension left her. Something like this must be peanuts to Leigh. It would be done and dusted in a couple of weeks. Leigh would bluster and bullshit and write a couple of letters in stiff legalese, Stella would crawl off, and the whole thing would be dropped.

“You need to sign the cost agreement, provide me with more information, and deposit twenty thousand dollars into our trust account, and I can get started.” She picked up the phone. “Grizz, can you bring me the information sheet on defending personal injury claims? I’m taking on Nina Pellegrini.”

Nina sat frozen in her chair. Twenty grand? She must have misheard. No one could possibly charge that. Even given the opulence of the office, she’d figured on a couple of thousand at worst. Distantly, she realised Leigh was saying something; those glossy raspberry lips were moving, but it was as if she were underwater. Everything was blurry, and Leigh’s voice had a slow and distant quality.

“Nina?”

Leigh waited for her response. Probably her clients usually nodded and wrote a cheque for twenty grand as if they were buying a latte.

“Did you say twenty thousand dollars?” That was what Leigh had said—she was sure it was—but she had to be certain.

“Yes. You can transfer the money when you’re ready to begin. However, you have a time frame within which to respond, and that’s only ten days away. So I suggest you don’t delay.”

“I don’t have twenty grand. I didn’t think it would be that much.”

Leigh frowned. “Then I suggest you approach your bank as soon as possible. Set up a line of credit against the property.”

“I can’t. The property’s mine, but I’m forbidden to borrow against it. It was a term of Gran’s will.”

“Is there someone who can lend you the money? Family?”

Nina shook her head. She was starting to feel like a puppet, pulled hither and thither by Leigh’s words but always in the wrong direction. Her stomach contracted as if she’d swallowed an ice block. “I thought it wouldn’t take much. A few letters over a couple of weeks.”

Leigh’s lips compressed. “I’m sorry, but no. It’s more complicated than that. Look, if you don’t have the money for legal fees, then I suggest you make a quick offer to settle. You’ll almost certainly have to pay something anyway—these things seldom go away. The mother’s a single parent, I think you said?”

“Yes. Money’s tight for her.”

“Then write a letter denying liability but offering a commercial settlement for a quick resolution. Offer ten thousand and leave it open for seven days. If the mother is financially strapped, it will probably be tempting.”

Nina could barely force the words past the lump in her throat. “I don’t have that much money.” How could she have been so naive, so utterly stupid? She was completely out of her depth here. She’d been good to Stella and Billy; she’d taken one look at Billy’s eager face when he had seen the ponies, and her big, soft heart had urged her to take him on. And look where that had gotten her: a fancy office on the twentieth floor of one of the ritziest office buildings in Sydney, being stared at by a lawyer who probably spent more on a restaurant meal than Nina spent on a week’s worth of groceries.

Nina could no more raise ten thousand than she could ride Mr Petey to the moon. She could already imagine the bank manager’s apologetic face if she approached him for a loan. Ten grand. It was impossible.

“How about offering two grand?” Nina tried a smile, but it felt more like a grimace.

Leigh’s eyes softened for a moment. “I’m sorry, but even to someone on a low income, two thousand will sound like peanuts.”

“It’s not peanuts to me.”

“I’ll ask Grizz to give you the contact details for community legal. They won’t be able to represent you, but they might offer more advice.”

“Thank you.”

A tap on the door and Grizz entered the room. She set some papers on the desk and smiled at Nina. “Would you like a cup of tea while you complete the forms?” Her broad face seemed like a safe harbour after Leigh’s remote coolness.

“There’s no need for that, Grizz,” Leigh said. “Nina is just leaving. Can you bring her the contact details for community legal? She’ll be in reception.” She stood and held out her hand. “Thank you for considering us. I’m sorry we can’t be of assistance.”

Nina stood. Her legs were shaky, as if she’d galloped circuits of Randwick racecourse. “Thank you for your time, Ms Willoughby. I’m sorry it was a waste for you.”

Leigh inclined her head. “No problem. I wish you the best of luck.”

Head high, Nina walked through the door.

“To the left,” Grizz said from behind her.

Nina didn’t trust her voice, so she simply walked to the reception. She should have known the second she set foot in this palace that it wouldn’t be cheap. Opulence like this didn’t come for nothing. She was out of her depth. Banksia Farm’s lived-in shabbiness wound through her mind, and the need to be home curled on the couch consumed her. She would have to figure out what to do. She would need to find money.

Tears pricked at the back of her eyes as she walked the quiet corridor to reception, and she willed them not to fall. Leigh must be worth a fortune. Weren’t lawyers some of the richest people in Sydney?

No wonder. No bloody wonder.

Chapter 3

Leigh stared at her computer screen. Incoming emails rolled past, the usual dozens and dozens that marked the start of any workday. She ignored them. Grizz would arrive soon, and she would sift through those same emails and handle what she could, which would be most of them. Then Grizz would grab money out of their joint fund, descend twenty floors to the coffee shop in the foyer, and return with a coffee for each of them. For fifteen minutes, they would update each other on the priorities for the day and progress on files while they sipped coffee. Generally, they shared a snippet of their private lives too.

Leigh switched screens and opened the Defence on the Matheson matter. She typed quickly, rebutting sections of the claim, flagging others for Grizz to research.

She was engrossed when Grizz slid the door open with her foot, limped across the carpet, and set the coffees on Leigh’s desk. “End-of-the-month muffins. They’re raspberry and white chocolate.” She added a paper bag. “We made budget; all’s right with the world.” She sat opposite and took a muffin, then slid the bag across to Leigh.

They were still warm. Leigh’s mouth watered, and she took a bite. “These are so good.”

“My favourite,” Grizz said around a mouthful.

Leigh studied her. “Are you limping? Again?”

Grizz shuffled in her chair. “It’s nothing. Not much anyway.”

Leigh took another bite of muffin. “Spill. Was this from last night’s activities?”

Grizz sighed. “Bryan and I went to the indoor climbing wall at Parramatta. Just don’t tell me a forty-nine-year-old woman shouldn’t be scaling cliffs. My creaky hips aren’t that bad, and I thought I’d be okay.”

“Is it bad? Do you need some time off?”

Grizz swallowed a huge mouthful of muffin. “No, I’m fine. It’s just a broken toe.” She glared at the muffin as if it were responsible for her injuries. “And I’ve twisted my lower back. I have no idea how that happened.”

Leigh smothered a smile. Grizz might be the best paralegal in Sydney, but she was also the most accident-prone. And she refused to succumb to her age. “Let me know when you’re going to the chiropractor.”

“This afternoon at three.”

“No problem. Take as long as you need.”

Grizz could have all the time off she needed. She’d make the time up—and more—as she always did.

Leigh waited until the muffin was gone before getting down to business. “Liability response is due on the Tran file today. Please draft a denial. Also, can you call Peter Nolan again and ask for the employment records? Be stern.”

Grizz nodded. “My speciality.”

Leigh flashed a grin. “That’s why you’re the one calling him.”

Grizz picked up her coffee. “Remember Nina Pellegrini from two days ago?”

Leigh nodded. Nina Pellegrini was not the sort of woman Leigh would forget in a hurry. She had beautiful hair, shiny and lustrous like polished mahogany, pulled back from her face in a ponytail. And then there were the clothes—an odd mix of dated styles. Nina was intriguing; she wasn’t just a corporate drone in a suit.

“She appeared in reception and asked to see you,” Grizz said. “I’ve talked with her. She still doesn’t have the money for fees, but she wants to persuade you to take her on pro bono.”

Nina’s intense figure flashed into Leigh’s mind: her huge, dark eyes, her naivety that things would work out without money. She wasn’t the usual sort of client, and it wasn’t the usual sort of case. But to take her on for free?

“I told her that your pro bonowork was limited,” Grizz continued, “and that her case was problematic for us in that it involved a child. The public can get emotional when children are hurt.”

“You’re right. Thanks.”

“She smiled, very sweetly, very politely, and said she realised that, but she still wanted a chance to talk to you.” Grizz sipped her coffee. “I said again you wouldn’t take her on, but she settled back in the reception chair, took out a book, and said she wouldn’t leave until she’d had a chance to persuade you.”

Leigh raised her eyebrows. “She could be in for a long wait.”

“I said that. But she’s not causing any problems. Chantelle on reception says she’s perfectly polite, and her only other request has been for a glass of water.” Grizz hesitated. “I read your notes. There’s something not quite right about that claim against her, but I can’t put my finger on it.”

“The mother delayed bringing a claim, and in the meantime, the child had been around at the farm with carrots for the pony. That’s odd but not that unusual.”

“Maybe.” Grizz’s rather plain face was thoughtful. “Anyway, at Nina’s request, I said I’d tell you she was here. Which I’ve now done.”

“Please tell her again that I’m not able to see her.”

“Will do, boss.” Grizz stood and gathered the empty cups. “I’ll get back to the grindstone.” She left, closing the door behind her.

Leigh worked steadily with no distractions for an hour until her neck ached from hunching. She kicked off her high heels and padded on stockinged feet over to the window.

Twenty storeys below, Sydney buzzed like a termite mound. Traffic, crowds, planes overhead—people going about their day. She glanced over to where she had a tiny glimpse of the harbour, sparkling blue in the sunshine. A ferry chugged past, and a flotilla of small yachts tacked hither and thither, their bright sails standing out like jewels on the water.

Who had the day off on a Wednesday to go sailing? There were so many boats out there; they couldn’t all be sailed by retirees or the superrich. She sometimes sailed on a friend’s yacht but only on weekends when he couldn’t get enough of his regular crew—and Leigh didn’t enjoy it enough to make the bigger commitment.

With a final glance at the world outside, Leigh returned to work.

Around one thirty, the hunger pangs in her stomach upped the level to a roar. She took off her glasses and rubbed her eyes. Maybe Grizz hadn’t gone out for lunch yet and could pick something up for Leigh on her way back. Grizz’s phone clicked over to voicemail; she must have already left on her break.

Leigh stood and picked up her bag. She’d nip out and pick up a salad to eat at her desk. She smoothed down her skirt with her palm and headed for the lift.

As she entered reception, a woman there put down her book and surged to her feet.

Nina Pellegrini. How could Leigh have been so absent-minded as to forget she might still be there?

“Ms Willoughby.” Nina stood directly in front of her so that Leigh was forced to come to a stop or brush past her. “I understand from your paralegal that you don’t feel you can help me, but I only ask for ten minutes of your time.”

“I’m sorry, I only have a few minutes to grab lunch before my next appointment.” It was a lie, but Nina wouldn’t know that.

“Then let me buy you lunch. Ten minutes, Ms Willoughby—Leigh—that’s all. Then if you still can’t help me, I’ll leave you alone.”

Nina’s face was pinched, and her eyes had an overlay of worry. Dark circles under her eyes stood out even against her tanned face. “Please,” she said again.

Leigh looked at Nina. The woman was obviously on edge. Her fingers clasped her bag so tightly her knuckles were white. One tiny part of Leigh’s mind softened. Nina was a woman, a mother, and, from the look of her, a battler. Nina was the sort of person Leigh had thought she’d be helping when she became a lawyer. A genuine person having a hard time with the law through misfortune. But somewhere along the way, Leigh had been sucked into the world of insurance law, helping major corporations pay out as little as possible to injured people.

Leigh tightened her lips. They were not alone in reception. There were clients there, real clients, and although they appeared absorbed in magazines, Leigh would bet her BMW they were avidly listening. It would look bad if she dismissed Nina. “Walk with me. It’s a five-minute walk to the café. Tell me what’s on your mind.”

Once they were on the street, Leigh turned to Nina. “Talk.” She started walking.

“I still don’t have the money to pay you,” Nina said. “Let’s get that out of the way first. But I would like you to take me on anyway. Pro bono. I can’t do it without you. I researched you. Saw an article about you in a business magazine. You are, quite simply, the best there is.”

Leigh shrugged. “Grizz already told you the reasons why I won’t take you on.”

“My grandparents bought Banksia Farm seventy years ago when they were just married. They had a dream of self-sufficiency. But as Sydney expanded, it became harder for them. Things cost more, and that’s when they decided to run Banksia Farm as a place for city kids to enjoy a rural lifestyle. Do you know there are kids in Sydney who think that milk is manufactured in cartons? They have no idea it comes from a cow. They’ve never seen a cow.” Nina drew a breath.

“I’m not sure what this has to do with me.” Leigh quickened her pace.

“This is what the farm’s about, Leigh. Being around animals teaches kids things they can’t learn in a classroom. They learn to be kind to small, helpless things. They learn responsibility, to think for themselves, and they learn a work ethic.”

They parted around a group of businessmen, each with a mobile phone held to his ear.

“Kids need the farm. And special needs kids and those from families who are just getting by need it more than most. A group of kids who have Down syndrome comes once a fortnight, and they take it in turns to ride. I don’t charge them. Sometimes, nurses from the university hospital bring terminally ill kids. Most of those kids soon go into hospice care. The community needs Banksia Farm.”

“What you do is admirable.” It was. A community for kids—which must make it harder for Nina to stomach that one of the kids she’d helped was likely to bring about the closure of the farm. A pang shot through Leigh’s belly that wasn’t entirely due to hunger. She slowed in front of a café. “This is where I get lunch.”

“I’ll get it for you.” Nina’s mouth set in a determined line. She pushed past Leigh and up to the counter. “What will you have?”

There were two stools at the bench by the window. Nina perched on one and clasped her glass of water. She hadn’t ordered anything to eat.

“If Billy wins his claim, I will have to sell Banksia Farm to pay him. There is no way around that. I won’t have any problem selling—indeed, there’s a very persistent developer who’s made me a couple of offers already. Banksia Farm is no longer in the bush; it’s surrounded by housing estates, and blocks that size are almost impossible to come by in the greater Sydney area. They could put a high-density development there or even a shopping centre.”

“You’d do well, I’m sure. A block that size, you’d make enough to pay Billy and buy a house in the same area.” Leigh picked at her salad.

“You still don’t get it.” Nina’s hair had worked loose from her tight ponytail. Strands hung around her face. “This isn’t about money. It’s about keeping the farm going for the kids who need it. Like Billy. Yes, I know he’s the cause of the problem right now, but Billy is exactly the sort of kid who needs to come to Banksia Farm. He comes out of himself when he’s there. He loves the place.”

Nina leant forward and touched Leigh’s hand, stilling it. Her touch was light, but there was an intensity to it, a burning desire for something. Nina’s touch screamed of a passion for life, for helping people, for doing the right thing. She was everything Leigh had been once, before she gained the office on the twentieth floor with harbour glimpses and partner on her business card.

“Please, Ms Willoughby—Leigh. Please help me. Not for me but for the kids who need Banksia Farm.”

Leigh studied Nina’s hand where it lay on her own.

Nina must have sensed the gaze, and she removed her hand. “Billy was hurt, but I don’t think it was my fault. And this is going to sound mean, but I don’t think he’s as badly hurt as the claim makes out. A broken arm and a concussion? That shouldn’t change his life. But you read that claim form; it makes Billy out to be incapacitated for life. Why should so many other kids suffer for that?”

Leigh ate her salad. Nina’s words twined around her mind. Defending the claim should be straightforward. Sure, Nina would almost certainly have to pay out something, but it shouldn’t be much. Maybe one of the junior lawyers in the firm would take it on pro bono.

She looked over at Nina. Her head was bowed, and her fingers pleated the material of her skirt. It was a vivid pink, similar to the one she had worn for her appointment two days ago, but this one was older, shabbier. They weren’t the sort of clothes one wore to meet with a top lawyer.

“Look, you really don’t need me for this.” Leigh put her fork down. “It’s straightforward. What I’ll do is put you in touch with Sarah Jackson, one of the other lawyers in my firm; she should be able to help you pro bono.”

“No. Sarah’s probably a fine lawyer, but I want you. It’s that important.”

Irritation flared. All clients thought their claim was important enough to warrant a top lawyer, but the reality was that few claims merited her attention. But there was something about Nina that tugged her, reminded her of something long neglected in her own life. Nina’s eyes, wide and pleading, were like a doe’s eyes. Soft, brown, about to be trampled on.

“Come and see the farm for yourself. You can just turn up; it’s that sort of place. Then you’ll see why I can’t lose it, why the community needs it.”

Leigh pushed away the remains of her salad. “I’ll think about it. That’s the best I can do. And in fairness to you, I’ll let you know by early next week so you’ll have time to find someone else if I can’t help you.” Part of her wondered why she was even making this concession. She’d think about it, yes, but she already knew what the answer was. She should tell Nina no and be done with it. Nina would get by. And even if she didn’t, well, it wasn’t her concern.

“Thank you.” Nina’s hands untwisted in her lap. “I hope you come out and see what we’re doing. You can meet Mr Petey.”

“Your husband?”

A swift grin darted across Nina’s face and was equally swiftly hidden. “No. Mr Petey’s the pony Billy was riding. I don’t have a husband. Or a wife for that matter.”

Oh. Now that was news. Leigh tamped down the question on her lips, one about wives. Nina wasn’t a client, not yet, maybe not ever, but that didn’t mean she was going to ask questions that would lead to shared knowledge, maybe something in common. A community in common. She stood and offered a small smile. “I’ll get back to you. Thank you for lunch.”

Nina rose. “You’re welcome. I look forward to hearing from you.”

Leigh strode away, focussing on the street. If she glanced back, would she see Nina looking after her? Why did that even matter?

“I’ve done some research.” Grizz stood in front of Leigh’s desk with a sheaf of papers. They looked like printouts from the internet.

“Oh? Are you going parasailing this weekend or waterskiing?”

“Neither. At least not until my toe has healed. Bryan wants to go camping anyway.”

“A nice sedate caravan park by the beach?” There was no way Grizz would stay somewhere like that, and her husband was the same. Their idea of camping was a bivouac halfway up a mountain.

“Pft.” Grizz scowled. “There’ll be plenty of time for that when I’m old. No, I’ve been researching Banksia Farm.” She placed the papers on the desk, sat, and crossed one ankle over her thigh. “It’s fairly well known—indeed, I’d already heard of it. There’s a waiting list to join their Barn Kids program, and there are several newspaper articles singing its praises. However, its business structure leaves a lot to be desired. It’s not a limited company, which leaves Nina wide-open.”

Leigh pulled the papers over. “What sort of idiot doesn’t register a company to protect her assets?”

“An uninformed person?” Grizz shrugged. “Seems to me she’d have a shot at operating as a registered charity.”

“I told her I’d think about taking her on pro bono.” Leigh looked up.

Grizz nodded as if she had expected as much. “Your diary is free tomorrow afternoon if you want to drive out there and take a look.”

“How many clients did you have to move to free that up?”

“Only two. You could do with more pro bono, y’know.” A smile softened Grizz’s face under the helmet of grey hair.

“And you want it to be Nina?”

“She seems like a deserving case.”

“Grizz, you soft-hearted old sook.” Leigh tried to suppress her grin.

“Don’t tell Bryan. He thinks I’m a hard-bitten old cow, and I like it that way.”

“I know your gooey side, but my lips are sealed.”

“So you’ll go out to the farm tomorrow?”

“No. I appreciate you freeing up my diary, but I don’t have the time for pointless jaunts. I’ll use the time to prepare for the Mason trial.”

“You’re throwing Nina to the wolves?”

“She’s really got to you.” Leigh sighed. “Call Sarah. See if you can sweet-talk her into taking it.”

“No worries.” Grizz rose and limped out of the office.

Her phone rang sometime later. Leigh glanced at it in irritation. The screen flashed James, the senior partner. That was a call she had to take.

“What’s this I hear about you shirking pro bono?” His voice boomed out. “Sarah called me. Some little case you tried to shift to her. Sarah already has half-a-dozen pro bono matters, and she’s under the pump for a big commercial trial. How many pro bonos have you got?”

Leigh wracked her brain. “Two, maybe three.”

“Not enough. We’re a big firm. We have obligations. Make time, Leigh. If the case is a total crock, that’s different, but otherwise, get it done. Or do what everyone else does and hand it off to your paralegal.” The line went dead.

Leigh compressed her lips. James’s manner was as abrasive as road gravel, but he always got his points across. Sighing, she flicked to her calendar. She was still free the next afternoon. She’d go out to Banksia Farm and at least take a look.